Conservatism in the United States: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 394557158 by 99.74.245.187 (talk) test edit |

NimrodNorth (talk | contribs) →External links: added an item |

||

| Line 654: | Line 654: | ||

*[http://www.vdare.com/gottfried/041104_kirk.htm Paul Gottfried, "How Russell Kirk (And The Right) Went Wrong"] |

*[http://www.vdare.com/gottfried/041104_kirk.htm Paul Gottfried, "How Russell Kirk (And The Right) Went Wrong"] |

||

*[http://photo.newsweek.com/2010/4/conservative-reactionary-movements.html A History of Conservative Movements] - slideshow by ''[[Newsweek magazine]]'' |

*[http://photo.newsweek.com/2010/4/conservative-reactionary-movements.html A History of Conservative Movements] - slideshow by ''[[Newsweek magazine]]'' |

||

*[http://www.charleschurchyard.com/conservatism.html "American Conservatism (So-Called)"] - How it differs from the traditional, European variety. |

|||

{{North America topic|Conservatism in}} |

{{North America topic|Conservatism in}} |

||

Revision as of 22:36, 6 November 2010

Conservatism in the United States is a concept which has evolved over the history of the country, encompassing somewhat different political stances in various eras. The history of American conservatism has been marked by tensions and outright contradictions, with intellectual debates not only between types of anti-communists and anti-statists, but between traditionalist and individualists who affirmed the primacy of religion, politics, or economics[1] The first sustained political movement that tried to bring together most of the different strands appeared in the 1950s.[2] Before this, however, Allitt (2009) finds that, "Certain continuities can be traced through American history. The conservative 'attitude' ... was one of trusting to the past, to long-established patterns of thought and conduct, and of assuming that novelties were more likely to be dangerous than advantageous."[3] Historian Gregory Schneider identifies several constants in American conservatism: respect for tradition, support of republicanism, preservation of "the rule of law and the Christian religion", and a defense of "Western civilization from the challenges of modernist culture and totalitarian governments."[4] From the late 19th century onward, conservatives have been dedicated to preventing the rise and spread of socialism and communism[5][6]

The modern conservative movement is often identified with the ideas in Russell Kirk's The Conservative Mind, published in 1953.[7] In 1955, William F. Buckley, Jr. founded National Review, a conservative magazine that included traditionalists, such as Kirk, along with Roman Catholics, some libertarians, and anti-communists. This bringing together of separate ideologies under a conservative umbrella was known as "fusionism". Modern conservatism became a major political force in 1964, when Barry Goldwater, a U.S. Senator from Arizona and author of The Conscience of a Conservative (1960), won the Republican presidential nomination after a fierce contest. He lost badly in the national election but permanently shifted the party to the right. In the 1970s moral issues—abortion, sexuality, and the family—became politically prominent and conservatives staked out distinctive positions, often with grassroots support from religious organizations such as the Moral Majority.

In the 1980s President Ronald Reagan solidified conservative Republican strength with tax cuts, deregulation, a policy of rolling back Communism (rather than just containing it), a greatly strengthened military, and appeals to family values, Christian morality, and limited government. The Reagan model became the conservative standard for social, economic and foreign policy issues, and that era of American history became known as the "Reagan Era."[8]

Core conservative beliefs in the 21st century include reduced government regulation of business and banking,[9] resistance to world government and to environmentalism, support for Israel[10] and for American military intervention overseas,[11] opposition to abortion and homosexuality, support for Christian education in the public schools,[12][13] support for the right to bear arms,[14] securing the U.S borders and strict enforcement of the law,[15] and a sharp reduction in taxes.[16][17][18] As of June 2010[update], 40% of American voters identify themselves as conservatives, 36% as moderates, and 22% as liberals, though a strong majority of both liberals and conservatives describe themselves moderate.[19][20]

The meaning of conservatism in America has little in common with the way the word is used in the rest of the world. Since the 1890s conservatism has been chiefly associated with the Republican Party However, before the 1990s many Southern Democrats were conservatives, and they played a key role in the Conservative Coalition that controlled Congress. In the 21st century about 30% of the Blue Dog Coalition of moderate-to-conservative Democrats are Southerners.[21]

History

The United States has never had a national political party called the Conservative Party. All major American political parties support the republican and liberal ideals on which the country was founded in 1776, with an emphasis on liberty, pursuit of happiness, rule of law, opposition to aristocracy, and emphasis on equal rights. Political divisions inside the United States have seemed minor or trivial to Europeans, where the divide between the Left and the Right led to very high polarization, starting with the French Revolution.[22]

Since 1776 there have been no American spokesmen for the European ideals of "conservatism" such as an established church and a hereditary aristocracy. Rather, American conservatism is a reaction against utopian ideas of progress.[23] Russell Kirk saw the American Revolution itself as "a conservative reaction, in the English political tradition, against royal innovation".[24]

In the 1790s Jeffersonian Democracy arose in opposition to the elitism of the Federalist Party, and fears that it intended to impose a monarchical system like Britain's. While the Jeffersonians admired the French Revolution and were primarily liberal, they also opposed a strong federal government and activist judges—themes later picked up by conservatives.[25] The word "conservative" was coined in 1819 by the French politician Chateaubriand).[26] By the 1830s, conservatism came to be identified with the Whig Party, which supported banks, business and modernization of the economy, while opposing the Jacksonian democracy which represented poor farmers and the urban working class. They chose the name "Whig" because it had been used by patriots in the Revolution. Daniel Webster and other Whig leaders referred to their new political party as the "conservative party", and they called for a return to tradition, restraint, hierarchy, and moderation.[27]

During the American Civil War, both sides claimed that they, and they alone, were the champions of the conservative cause. The South fought to preserve the tradition of states rights and slavery. The North fought to preserve the Union and the principle of freedom for everyone.[28] During the Reconstruction Era, conservative meant opposition to the Radical Republicans, who wanted to grant freed slaves political power as well as full-fledged citizenship.[29]

American Revolution

American conservatives today strongly admire the Founding Fathers, and demand a return to their values. Historians have given considerable attention to the values of the Founding Fathers, and to conservatism in America at the time of the Revolution. By the 1750s and 1760s some colonial institutions had conservative aspects. These included political power held by small elites, established churches in half the colonies,[30] entailed property rights in Virginia, large landholdings operated by riotous tenants in New York, and slavery in every colony. Although the colonists lived under the freest government in the European world,[31] they were fiercely determined to protect and preserve their historic rights. By the 1750s most Americans owned property and could vote in elections that controlled local government. Local and colonial taxes were low, and imperial taxes were few.[32][33][34][35]

By the 1770s there was a large element tied to the British Empire, including wealthy merchants involved in international trade, and royal officials and patronage holders. Most of these conservative elites and their followers who remained loyal to the Crown are called Loyalists or "Tories". The Loyalists were "conservatives" in that they tried to preserve the status quo of Empire against revolutionary change. Their leaders were men of wealth and property who loved order, respected their betters, looked down on their inferiors, and feared democratic rule by the rabble at home more than rule by a distant aristocracy. When it came to a choice between protecting their historic rights as Americans or remaining loyal to the King, they chose King and Empire.[36][37]

The patriots who fought the Revolution did so in the name of preserving traditional rights of Englishmen—especially the right of "no taxation without representation"; they increasingly opposed attempts by Parliament to tax and control the fast-growing colonies. When the British cracked down hard on Boston after the Boston Tea Party in 1773, the patriots organized colony-by-colony and were ready to fight.[38] Fighting broke out in spring 1775, and all Thirteen Colonies rallied to expel royal officials. The colonies formed a Congress that became the de facto national government, raised an army under George Washington, won support from France, and declared independence as the "United States of America" in July 1776. The patriots formed a consensus around the ideas of republicanism, whereby the people were sovereign (not the king), every citizen had equal legal rights, elected assemblies made the laws, inherited titles, established armies and churches were rejected, and corruption of the sort practiced by royalty was repudiated.

Labaree (1948) has identified eight characteristics of the Loyalists that made them essentially conservative in opposing Independence. Psychologically they were older, better established, and resisted innovation. They thought resistance to the Crown—the legitimate government—was morally wrong. They were alienated when the Patriots' resorted to violence, such as burning houses and tarring and feathering. They wanted to take a middle-of-the road position and were angry when forced by the Patriots to declare their opposition. They had a long-standing sentimental attachment to Britain (often with business and family links). They were procrastinators who realized that independence was bound to come some day, but wanted to postpone the moment. They were cautious and afraid of anarchy or tyranny that might come from mob rule. Finally they were pessimists who lacked the confidence in the future displayed by the Patriots.[39][40][41] Loyalists willing to accept republican principles remained after the war—80% stayed on—while those who rejected republicanism went elsewhere in the British Empire (mostly to Canada), taking their conservatism with them. The new principles of the Revolution became the core American political values agreed to by all sides, and became part of the core principles of what is now called American conservatism.

Thus the American Revolution disrupted the old networks of conservative elites. The departure of so many royal officials, rich merchants and landed gentry destroyed the hierarchical networks that had dominated most of the colonies. In New York, for example, the departure of key members of the DeLancy, DePester Walton, and Cruger families undercut the interlocking families that largely owned and controlled the Hudson Valley. Likewise in Pennsylvania, the departure of powerful families—Penn, Allen, Chew, Shippen—destroyed the cohesion of the old upper class there. New men became rich merchants but they shared a spirit of republican equality that replaced the elitism and the Americans never recreated such a powerful upper class. One rich patriot in Boston noted in 1779 that "fellows who would have cleaned my shoes five years ago, have amassed fortunes and are riding in chariots."[42] Nevertheless the conservatism of the Loyalists did not die out. Eight in ten remained in America after the Revolution. For the most part, they avoided politics; certainly they never tried to form a revanchist movement seeking a return to the Empire. Samuel Seabury remained and abandoned politics but became the first Episcopalian bishop in the United States, rebuilding a church that appealed to the upper class that still admired hierarchy, tradition, and historic liturgy.[43]

Federalists

The Federalist Party, dominated by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton used the presidency of George Washington to promote a strong nation capable of holding its own in world affairs, with a strong army and navy, capable of suppressing internal revolts (such as the Whiskey Rebellion) and founding the national finances on a sound basis while winning the broad support of the financial and business community.[44] Intellectually, Federalists, while devoted to liberty held profoundly conservative views atuned to the American character. As Samuel Eliot Morison explained, They believed that liberty is inseparable from union, that men are essentially unequal, that vox populi [voice of the people] is seldom if ever vox Dei [the voice of God], and that sinister outside influences are busy undermining American integrity.[45] Historian Patrick Allitt concludes that Federalists promoted many conservative positions, including the rule of law under the Constitution, republican government, peaceful change through elections, judicial supremacy, stable national finances, credibile and active diplomacy, and protection of wealth.[46]

The Federalists were dominated by businessmen and merchants in the major cities and was supportive of the modernizing, urbanizing, financial policies of Hamilton. These policies included the funding of the national debt and also assumption of state debts incurred during the Revolutionary War (thus allowing the states to lower their own taxes and still pay their debts), the incorporation of a national Bank of the United States, the support of manufactures and industrial development, and the use of a tariff to fund the Treasury. In foreign affairs the Federalists opposed the French Revolution. Under John Adams they fought the "Quasi War" (an undeclared naval war) with France in 1798–99 and built a strong army and navy. Ideologically the controversy between Jeffersonian Republicans and Federalists stemmed from a difference of principle and style. In terms of style the Federalists distrusted the public, thought the elite should be in charge, and favored national power over state power. Republicans distrusted Britain, bankers, merchants and did not want a powerful national government. The Federalists, notably Hamilton, were distrustful of "the people," the French, and the Republicans.[47] In the end, the nation synthesized the two positions, adopting representative democracy and a strong nation state. Just as importantly, American politics by the 1820s accepted the two-party system whereby rival parties stake their claims before the electorate, and the winner takes control of the government. As time went on, the Federalists lost appeal with the average voter and were generally not equal to the tasks of party organization; hence, they grew steadily weaker as the political triumphs of the Republican Party grew after 1800. After 1816 the Federalists had no national influence apart from John Marshall's Supreme Court. They had some local support in New England, New York, eastern Pennsylvania, Maryland and Delaware.

The "Old Republicans," led by John Randolph of Roanoke, refused to form a coalition with the Federalists and instead set up a separate opposition since James Madison, Albert Gallatin, James Monroe, John C. Calhoun and Henry Clay had in effect adopted Federalist principles by purchasing the Louisiana Territory, chartering the Second national bank, promoting internal improvements (like roads), raising tariffs to protect factories, and promoting a strong army and navy after the failures of the War of 1812.

Lincoln's conservatism

In his Cooper Union speech, Lincoln spoke of the sectionalism which was fracturing the country as a result of slavery; the Republican Party was new proclaimed its goal of putting slavery on the path to extinction. Lincoln and his party were called radical, abolitionist and destructive, but he counted himself among the earliest defenders of conservative principles, which was in essence a defense of time-honored, traditional values. Lincoln said that out of the 39 framers of the Constitution, 23 of the 39 voted on whether to prevent the spread of slavery, and that 21 of the 23 voted in favor of doing so. Lincoln explicitly called his position on slavery "conservative" and that it was the pro-slavery South that was radically breaking with the Founding Fathers.[48] Harris (2007) finds that Lincoln's "reverence for the Founding Fathers, the Constitution, the laws under it, and the preservation of the Republic and its institutions undergirded and strengthened his conservatism.".[49]

Southern conservatism

White Southerners took a lesson from the Reconstruction era that the radical experiments by Northern reformers violated the rights of white men and were inevitably tied to corruption. The race-based conservatism in the American South differed from the business-based conservatism in the North in its strong support for white supremacy, and insistence on a second-class powerless status for blacks, regardless of the Constitution. From 1877 to 1963, the "Solid South" voted for Democrats in almost all national elections; Democrats had firm control of state and local government in all southern states.

Fundamentalism, especially on the part of Southern Baptists, was a powerful force in Southern conservative politics beginning in the 1980s.[50]

The Gilded Age

There was little nostalgia and backward looking in the dynamic North and West during the "Gilded Age"—the boom decades that followed the Civil War. Business was expanding rapidly, with manufacturing, mining, railroads, and banking leading the way. There were millions of new farms in the prairie states. Immigration reached record levels. Progress was the watchword of the day. The wealth of the period is highlighted by American upper-class opulence, but also by the rise of American philanthropy (referred to by Andrew Carnegie as the "Gospel of Wealth") that used private money to endow thousands of colleges, hospitals, museums, academies, schools, opera houses, public libraries, symphony orchestras, and charities.[51]

Conservatives in the 20th Century, looking back at the Gilded Age, retroactively applied the word "conservative" to those who supported unrestrained capitalism. For example, Oswald Garrison Villard, writing in 1939, characterized his former mentor Horace White (1834–1916) as "a great economic conservative; had he lived to see the days of the New Deal financing he would probably have cried out loud and promptly demised."[52]

In this sense, the conservative element of the Democratic party was led by the Bourbon Democrats and their hero President Grover Cleveland, who fought against high tariffs and on behalf of the gold standard. In 1896, the Bourbons were overthrown inside the Democratic Party by William Jennings Bryan and the agrarians, who preached "Free Silver" and opposition to the power that banks and railroads had over the American farmer. The agrarians formed a coalition with the Populists and vehemently denounced the politics of big business, especially in the decisive 1896 election, won by Republican William McKinley, who was easily reelected over Bryan in 1900 as well.

Religious conservatives of this period sponsored a large and flourishing media network, especially based on magazines, many with close ties to the Protestant churches that were rapidly expanding thanks to the Third Great Awakening. Catholics had few magazines but opposed agrarianism in politics and established hundreds of schools and colleges to promote their conservative religious and social values.[53]

Modern conservatives often point to William Graham Sumner (1840–1910), a leading public intellectual of the era, as one of their own, citing his articulate support for free markets, anti-imperialism, and the gold standard, and his opposition to what he saw as threats to the middle class from the rich plutocrats above or the agrarians and ignorant masses below.[54][55]

The Gilded Age came to an end with the Panic of 1893 and the severe nationwide depression that lasted from 1893 to 1897.

Empire

As the 19th century drew to a close the United States became a major world power, having acquired overseas territories in Hawaii, Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. The two parties re-aligned in the election of 1896, with the Republicans, led by William McKinley, becoming the party of business, sound money, and assertive foreign policy, while the Democrats, led by William Jennings Bryan, became the party of the worker, the small farmer, "Free Silver", and anti-imperialism. Bryan was also popular with religious fundamentalists and white supremacists.[56]

Imperialism won out, as the election of 1900 ratified McKinley's policies and the U.S. possession of Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, the Philippines and (temporarily) Cuba. Theodore Roosevelt promoted the military and naval advantages of the U.S., and echoed McKinley's theme that America had a duty to civilize and modernize the heathen.[57][58] The supposed business, religious, and military advantages of having an empire proved illusory; by 1908 or so the most ardent imperialists, including Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Elihu Root[59] turned their attention to building up an army and navy at home and to building the Panama Canal. They dropped the notion of additional expansion and agreed by 1920 that the Philippines should become independent.[60][61]

Progressive Era

In the early years of the 20th century, Republican spokesmen for big business in Congress included Speaker of the House Joe Cannon and Senate Republican Leader Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island. Aldrich introduced the Sixteenth Amendment, which allowed the federal government to collect an income tax; he also set in motion the design of the Federal Reserve System, which began in 1913.[62] Pro-business conservatives supported many Progressive Era reforms, especially those opposed to corruption and inefficiency in government, and called for purification of politics. Conservative Senator John Sherman sponsored the nation's basic anti-trust law in 1890, and conservatives generally supported anti-trust in the name of opposing monopoly and opening up opportunities for small business.[63] The issues of prohibition and woman suffrage split the conservatives.

The "insurgents" were on the Left of the Republican Party. Led by Robert LaFollette of Wisconsin, George W. Norris of Nebraska, and Hiram Johnson of California, they fought the conservatives in a series of bitter battles that split the GOP and allowed the Democrats to take control of Congress in 1910. Teddy Roosevelt, a hawk on foreign and military policy, moved increasingly to the Left on domestic issues regarding courts, unions, railroads, big business, labor unions and the welfare state.[64][65] By 1910-11, Roosevelt had broken bitterly with Taft and the conservative wing of the GOP. In 1911-12 he took control of the insurgency, formed a third party, and ran an unsuccessful campaign for president on the Progressive Party ticket in 1912. His departure left the conservatives, led by President William Howard Taft, dominant in the Republican party until 1936.[66] The split opened the way in 1912 for Democrat Woodrow Wilson to become president with only 42% of the vote.

World War I

The Great War broke out in 1914, with Wilson proclaiming neutrality. Former president Theodore Roosevelt denounced Wilson's foreign policy, charging, 'Had it not been for Wilson's pusillanimity, the war would have been over by the summer of 1916." Indeed, Roosevelt believed that Wilson's approach to foreign policy was fundamentally and objectively evil.[67] He dropped the ill-fated Progressive Party and campaigned for the GOP. But Wilson gained many of the Progressive Party voters, and won a narrow victory in 1916. The GOP, under conservative leadership, regained Congress in 1918[68] and the White House in 1920.

1920s

Conservative Republicans returned to dominance in 1920 with the election of President Warren G. Harding, who called for a return to "normalcy." Tucker (2010) argues that the 1924 election marked the "high tide of American conservatism," as both major candidates campaigned for limited government, reduced taxes, and less regulation. A third-party candidate on the left won only 17% of the vote, as Calvin Coolidge scored a landslide.[69] Under Coolidge (1923–29) the economy boomed and the society was stabilized by moving to Americanize the immigrants already here, and not allowing many more in.

A representative conservative of the 1900-1930 era was James Beck, a lawyer under Presidents Roosevelt, Harding and Coolidge, and a congressman 1927-1933. His conservatism appeared in his support for nationalism, individualism, constitutionalism, laissez-faire, property rights, and opposition to reform. Conservatives like Beck saw the need to regulate bad behavior in the corporate world with the intention of protecting corporate capitalism from radical forces, but they were alarmed by the anti-business and pro-union proposals of Roosevelt after 1905. They began to question the notion of a national authority beneficial to big capital, and instead emphasized legalism, concern for the Constitution, and reverence for the American past.[70]

Anti-Communism

With the success of the Communist takeover of Russia in 1917, both American political parties became strongly anti-Communist. Within the U.S., the far Left split and an American Communist Party, emerged in the 1920s.[71] Conservatives denounced the movement as a subversion of American values and kept up relentless opposition until Communism collapsed in Russia in 1991. They paid special attention to Communist agents trying to change national policies and values in the U.S. government, the media, and academe. Conservatives gave enthusiastic support to anti-Communist agencies such as the FBI and the Congressional investigations of the 1940s and 1950s, particularly those led by Richard Nixon and Joe McCarthy. They paid special attention to ex-Communists who exposed the system, such as Whittaker Chambers.[72]

Writers and intellectuals

Classic conservative writing of the period includes Democracy and Leadership (1924) by Irving Babbitt. The Efficiency Movement attracted Progressive Republicans like Herbert Hoover with its pro-business, quasi-engineering approach to solving social and economic problems.

Numerous literary figures developed a conservative sensibility and warned of threats to Western Civilization. In the 1900-1950 era Henry Adams, T. S. Eliot, Allen Tate, Andrew Lytle, Donald Davidson, and others feared that heedless scientific innovation would unleash forces that would undermine traditional Western values and lead to the collapse of civilization. Instead they searched for a rationale for promoting traditional cultural values in the face of an onslaught by moral nihilism based on historical and scientific relativism.[73]

Conservatism as an intellectual movement in the South after 1930 was represented by writers such as Flannery O'Connor and the Southern Agrarians. The focus was on traditionalism and hierarchy.[74]

Numerous former Communist or Trotskyite writers repudiated the Left in the 1930s or 1940s and embraced conservatism, becoming contributors to National Review in the 1950s. They included Max Eastman (1883–1969), John Dos Passos (1896–1970), Whittaker Chambers (1901–1961), Will Herberg (1901–1977), and James Burnham (1905–1987).[75]

Great Depression

The Great Depression which followed the 1929 stock market collapse led to price deflation, massive unemployment, falling farm incomes, investment losses, bank failures, business bankruptcies and reduced government revenues. Herbert Hoover's conservative economic policies failed to halt the depression, and in the 1932 presidential election, Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt won a landslide victory.

When Roosevelt tried to bring the country out of depression and ease the plight of the unemployed with the New Deal, conservatives fought him every inch of the way. The counterattack first came from conservative Democrats, led by presidential nominees John W. Davis (1924) and Al Smith (1928), who mobilized business men into the American Liberty League. Opposition to the New Deal also came from the Old Right, a group of conservative free-market anti-interventionists, originally associated with Midwestern Republicans led by Hoover and Robert A. Taft, the son of former President William Howard Taft. The Old Right accused Roosevelt of promoting socialism and being a "traitor to his class".

Vice President John Nance Garner worked with congressional allies to prevent Roosevelt from packing the Supreme Court with six new judges, so the court would not over-rule New Deal legislation as unconstitutional. U.S. Senator Josiah Bailey (D-NC) released the "Conservative Manifesto" in December 1937 which marked the beginning of the "conservative coalition" between Republicans and Southern Democrats.[76] Roosevelt tried and failed to purge conservative Democrats in the 1938 primaries, but all but one beat him back and the Republicans made nationwide gains in 1938. The Conservative Coalition generally controlled Congress until 1963; no major legislation passed which the Coalition opposed. Its most prominent leaders were Senator Robert Taft (R-OH) and Senator Richard Russell (D-GA). Robert Taft unsuccessfully sought the Republican nomination in 1940, 1948, and 1952, and was an opponent of American membership in NATO and of American participation in the Korean War.

Many conservatives, especially in the Midwest, in 1939-41 favored isolationism and opposed American entry into the World War II—and so did many liberals. (see America First Committee). Conservatives in the East and South were generally interventionist, as typified by Henry Stimson. However, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in Dec. 1941 united all Americans behind the war effort, with conservatives in Congress taking the opportunity to close down many New agencies, such as the bete noir the WPA.

Jefferson's image

In the New Deal era of the 1930s, Jefferson's memory became contested ground. Franklin D. Roosevelt greatly admired Jefferson and had the Jefferson Memorial built to honor his hero. Even more dramatic, however, was the reaction of the conservatives, as typified by the American Liberty League (comprising mostly conservative Democrats who resembled the Bourbon Democrats of the 1870-1900 era), and the Republican Party. Conservative Republicans dropped Hamiltonianism because it led to enlarged national government. Their opposition to Roosevelt's New Deal was cast in explicitly Jeffersonian small-government terms, and Jefferson also became a hero of the Right.[77]

Post 1945

Modern conservatism, which combines elements from both traditional conservatism and libertarianism, emerged following World War II, has its immediate political roots in reaction to the New Deal. In 1946, conservative Republicans took control of Congress and opened investigations into communist infiltration of the federal government under Roosevelt. Congressman Richard Nixon exposed Alger Hiss, a senior State Department official, as a Soviet spy. Senator Joe McCarthy in 1950-54 led investigations into the coverup of spies in the government, using careless tactics that allowed his opponents to effectively counterattack, and censure McCarthy formally in 1954. Meanwhile the major job of rooting out Communists from labor unions and the Democratic party was undertaken by liberals, such as Walter Reuther of the autoworkers union and Ronald Reagan of the Screen Actors Guild.[78] President Harry Truman adopted a rollback strategy against Communism in 1950 in Korea, planning to free the entire country by force. But when the Chinese entered he reversed positions, fired the conservative hero General Douglas MacArthur, and settled for containment, accepting the status quo at a cost of 37,000 Americans killed and a sharp decline in Truman's base of support.

1950-1980

Isolationism had weakened the Old Right, as shown by General Eisenhower's defeat of Senator Robert Taft for the GOP nomination in 1952. Eisenhower then defeated Truman by crusading against "Korea, Communism and Corruption." Eisenhower quickly ended the Korean War, which most conservatives now opposed and adopted a conservative fiscal policy while cooperating with Taft, who became the Senate Majority Leader. The regulatory and welfare policies of the New Deal were retained, with the Republicans taking credit for the expansion of Social Security.

Russell Kirk

While Republicans in Washington were tweaking the New Deal, the most critical opposition to liberalism came from writers. Russell Kirk claimed that both classical and modern liberalism placed too much emphasis on economic issues and failed to address man's spiritual nature, and called for a plan of action for a conservative political movement. He said that conservative leaders should appeal to farmers, small towns, the churches, and others.[79] This target group is similar to the core constituency of the British Conservative Party.

William F. Buckley

The most effective organizer and proponent of conservative ideas was William F. Buckley, Jr. (1925–2008), the founder of National Review in 1955 and a highly visible writer and media personality. There had been numerous small circulation magazines on the right before, but the National Review gained national attention and shaped the conservative movement, thanks to strong editing and a strong stable of regular contributors. Erudite, witty and tireless, Buckley inspired a new enthusiasm.[80]

Buckley assembled an eclectic group of writers: traditionalists, Catholic intellectuals, libertarians and ex-Communists. They included: Russell Kirk, James Burnham, Frank Meyer, Willmoore Kendall, L. Brent Bozell, and Whittaker Chambers In the magazine’s founding statement Buckley wrote:[81]

The launching of a conservative weekly journal of opinion in a country widely assumed to be a bastion of conservatism at first glance looks like a work of supererogation, rather like publishing a royalist weekly within the walls of Buckingham Palace. It is not that of course; if National Review is superfluous, it is so for very different reasons: It stands athwart history, yelling Stop, at a time when no other is inclined to do so, or to have much patience with those who so urge it.

Libertarians

Economists Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman and George J. Stigler engaged with various blocks of conservatives and advocated a return to classical liberal or libertarian policies and together provided a vigorous criticism of the welfare state and Keynesian economics.[82] William F. Buckley, Jr. formed the magazine the National Review in 1955 as a forum for these writers to voice their disagreements with modern liberalism and also with one another.

Judeo-Christian elements

By the 1950s conservatives were emphasizing the Judeo-Christian roots of their values[83] As economist Elgin Groseclose explained, it was ideas "drawn from Judeo-Christian Scriptures that have made possible the economic strength and industrial power of this country."[84] Barry Goldwater noted that conservatives "believed the communist projection of man as a producing, consuming animal to be used and discarded was antithetical to all the Judeo-Christian understandings which are the foundations upon which the Republic stands."[85] Ronald Reagan frequently emphasized Judeo-Christian values as necessary ingredients in the fight against communism. He argued that the Bible contains "all the answers to the problems that face us."[86] Belief in the superiority of Western Judeo-Christian traditions led conservatives to downplay the aspirations of Third World and to denigrate the value of foreign aid.[87][88]

The emergence of the "religious right" as a political force and part of the conservative coalition dates from the 1970s. As Wilcox and Robinson conclude, "The Christian Right is an attempt to restore Judeo-Christian values to a country that is in deep moral decline. ....[They] believe that society suffers from the lack of a firm basis of Judeo-Christian values and they seek to write laws that embody those values".[89] Especially important was the hostile reaction to the "Roe v. Wade" Supreme Court decision legalizing abortion, which brought together Catholics (who had long opposed abortion) and Fundamentalist Protestants (who were new to the issue.)[90]

John Birch Society

Robert W. Welch Jr. (1900–1985) founded the John Birch Society as an authoritarian top-down force to combat Communism. It had tens of thousands of members and distributed books, pamphlets and the magazine American Opinion. It was so tightly controlled by Welch that its effectiveness was limited, and it focused on calls to impeach Chief Justice Earl Warren, as well as supporting local police[91] Instead it became a lighting rod for liberal attacks, and indeed Welch was denounced by Goldwater, Buckley and other mainstream conservatives.

Internal disagreements

The main disagreement between Kirk, who would become described as a traditionalist conservative, and the libertarians was whether tradition and virtue or liberty should be their primary concern. Frank Meyer tried to resolve the dispute with "fusionism": America could not conserve its traditions without economic freedom. He also noted that they were united in opposition to "big government" and made anti-communism the glue that would unite them. The term "conservative" was used to describe the views of National Review supporters, despite initial protests from the libertarians, because the term "liberal" had become associated with "New Deal" supporters. They were also later known as the "New Right", as opposed to the New Left.

Goldwater

The conservatives united behind the unsuccessful 1964 presidential campaign of Senator Barry Goldwater, who had published The Conscience of a Conservative (1960), a best-selling book that explained modern conservative theory. Some support for the campaign came from the newly-formed Young Americans for Freedom, a project sponsored by William F. Buckley. In 1965 conservatives campaigned for Buckley as a third party candidate for Mayor of New York and in 1966 for Ronald Reagan, who was elected governor of California. Reagan increasingly dominated the conservative movement, especially in his failed 1976 quest for the Republican presidential nomination and his successful run in 1980.

Neoconservatives

A major development of the 1970s was the movement of many prominent liberal intellectuals to the right, many of them from New York City Jewish roots and well-established academic reputations. They had become disillusioned with liberalism, especially the foreign policy of détente with the Soviet Union.

Irving Kristol and Leo Strauss were the major founders of the movement. The magazines Commentary and Public Interest were their key outlets, as well as op-ed articles for major newspapers and position papers for think tanks. Activists around Democratic senator Henry Jackson became deeply involved as well. Prominent spokesmen include Gertrude Himmelfarb, Bill Kristol, Paul Wolfowitz, Lewis Libby, Norman Podhoretz, Richard Pipes, Charles Krauthammer, Richard Perle, Robert Kagan, Elliott Abrams and Ben Wattenberg. Meanwhile, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan was highly sympathetic but remained a Democrat. Neocons such as Irving Kristol, have promoted a support of Big Business.[17] Some went on to high policy-making or advisory positions in the Reagan and Bush administrations.

Some of Leo Strauss' influential neoconservative disciples included Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork, Paul Wolfowitz (who became Deputy Secretary of Defense), Alan Keyes (who became Assistant Secretary of State), William Bennett (who became Secretary of Education), Weekly Standard editor William Kristol, political philosopher Allan Bloom, writer John Podhoretz, college president John T. Agresto; political scientist Harry V. Jaffa; and Nobel Prize winning novelist Saul Bellow.

Conservatism in the South

The growth of conservatism within the Republican Party attracted White conservative Southern Democrats in presidential elections. A few big names switched to the GOP, including South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond in 1964 and Texas Governor John Connally in 1973. Starting in 1968 the GOP dominated most presidential elections in the South (1976 was the lone exception), but not until the 1990s did the GOP become dominant in state and local politics in the region. The Republicans built their strength among Southern Baptists and other religious Fundamentalists, among the middle class suburbs, and among migrants from the North, and Cubans in Florida. Meanwhile, starting in 1964, African American voters in the South began to show overwhelming support for the Democratic Party at both the presidential and local levels. They elected a number of Congressmen and mayors. By 1990 there were still many moderate white Democrats holding office in the South, but when they retired they were typically replaced by much more conservative Republicans, or by liberal blacks.[50]

Think tanks

In 1971 Lewis F. Powell Jr. urged conservatives to retake command of public discourse by "financing think tanks, reshaping mass media and seeking influence in universities and the judiciary." In the coming decades policies once considered outside the mainstream consensus—abolishing welfare, privatizing Social Security, deregulating banking, embracing preemptive war—were taken seriously and sometimes passed into law thanks to the work of the Heritage Foundation, the American Enterprise Institute, the Fox News Network, as well as numerous corporate lobbying organizations and university professorships.[92][93]

1970s: Nixon, Ford, Carter

The Republican administrations of President Richard Nixon (1969–74) and Gerald Ford (1974–77) were characterized by their emphasis on détente and on economic intervention through wage and price controls. Ford angered conservatives by continuing Henry Kissinger as Secretary of State and pushing his policy of détente with the Soviet Union. Conservatives finally found a new champion in Ronald Reagan, whose 8 years as governor of California had just ended in 1976, and supported his campaign for the Republican nomination. Ford narrowly won renomination but lost the White House. Liberal Democrats, who had made major gains in the 1974 midterm election, elected Jimmy Carter. Carter proved much too liberal for the conservative movement, too conservative for the mainstream of the Democratic Party, and too incompetent in foreign affairs to please anyone. Carter realized there was a strong national sense of malaise, for which he blamed the people, as inflation skyrocketed, interest rates soared, the economy stagnated, and prolonged humiliation resulted when Islamic militants in Tehran kept American diplomats hostage for 444 days in 1979-81.[94]

Reagan Era

Conservative ascent

In Tehran, Islamic militants released the hostages at the moment Ronald Reagan was sworn in. With its victory in 1980 the modern American conservative movement finally took power. Republicans took control of the Senate for the first time since 1954, and conservative principles dominated Reagan's economic and foreign policies, with supply side economics and strict opposition to Soviet Communism defining the Administration's philosophy. Reagan's ideas were largely espoused and supported by the conservative Heritage Foundation, which grew dramatically in its influence during the Reagan years as Reagan and his senior aides looked to Heritage for policy guidance.

An icon of the American conservative movement, Reagan is credited by his supporters with transforming the politics of the United States, galvanizing the success of the Republican Party. He brought together a coalition of economic conservatives, who supported his supply-side economics; foreign policy conservatives, who favored his staunch opposition to Communism and the Soviet Union; and social conservatives, who identified with his religious and social ideals. Reagan labeled the former Soviet Union the "evil empire." He was attacked by liberals at the time as a dangerous warmonger, but conservative historians assert that he decisively won the Cold War.[95]

In defining conservatism, Reagan said: "If you analyze it I believe the very heart and soul of conservatism is libertarianism. I think conservatism is really a misnomer just as liberalism is a misnomer for the liberals—if we were back in the days of the Revolution, so-called conservatives today would be the Liberals and the liberals would be the Tories. The basis of conservatism is a desire for less government interference or less centralized authority or more individual freedom and this is a pretty general description also of what libertarianism is."[96] Reagan's views on government were influenced by Thomas Jefferson, especially his hostility to strong central governments.[97] "We're still Jefferson's children," he declared in 1987. "Freedom is not created by Government, nor is it a gift from those in political power. It is, in fact, secured, more than anything else, by limitations placed on those in Government".[98][99] Likewise he greatly admired and often quoted Abraham Lincoln[100]

Supply-side economics dominated the Reagan Era[101] During his eight years in office, consumer prices rose by more than 50%, and the national debt more than doubled, from $907 billion in 1980 to $2.6 trillion in 1988.[102]

Since 1990

In 1992 many conservatives repudiated President Bush because he violated his promise, "Read My Lips: No New Taxes." He was defeated for reelection in 1992 in a three way race, with populist Ross Perot attracting considerable support on the right. Democrat Bill Clinton was stopped in his plan for government health care, and in 1994 the GOP made sweeping gains under the leadership of Newt Gingrich, the first Republican to become Speaker in 40 years. Gingrich overplayed his hand by cutting off funding for the Federal government, allowing Clinton to regain momentum and win reelection in 1996. The "Contract with America" promised numerous reforms, but little was accomplished beyond the ending of major New Deal welfare programs. A national movement to impose term limits failed to reach Congress (because the Supreme Court ruled that a constitutional amendment was needed) but did transform politics in some states, especially California

George W. Bush

In an extremely close race George W. Bush was elected president in 2000 after a contested recount in Florida, and brought a new generation of conservative activists to power in Washington. Bush cut taxes dramatically in a 10-year plan that is up for renewal in 2011. Bush forged a bipartisan coalition to pass "No Child Left Behind", which for the for the first time imposed national standards on public schools. The 9-11 Attacks unified the nation in a War against Terrorism, with invasions of Afghanistan in 2001 (which is still underway in 2010), and Iraq in 2003 (which was winding down in 2010). Bush won solid support from Republicans in Congress and from conservative voters in his reelection bid in 2004. When the financial system verged on total collapse in 2008, Bush pushed through very large scale rescue packages for banks and auto companies that conservatives in Congress very reluctantly supported. Some noted conservatives, including Richard A. Viguerie and William F. Buckley, Jr. concluded that Bush was not a conservative, either in foreign policy nor in domestic economic policy.[103][104]

2008

The Republican contest for the nomination in 2008 was a free-for-all, with maverick Senator John McCain the winner, facing the first Black US presidential candidate, Barack Obama. McCain chose Alaska Governor Sarah Palin as his running mate, and while greated by the establishment of the GOP with initial skepticism, she electrified the conservatives and has become a major political force on the right. The economic crisis of 2008 doomed McCain. Congress had already shifted to the left in 2006.[105]

In 2009-10 the GOP in Congress was unified in almost total opposition to the programs of the Democratic majority. They tried but failed to stop a $814 billion stimulus spending program, new regulations on Wall Street investment firms, and a bill to provide health insurance for all Americans. They did keep "cap and trade" from coming to a vote, and vow to continue to work to convince Americans that burning fossil fuel does not cause Global warming.[106]With a Democratic president, many conservatives have shifted their stance on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan one hundred eighty degrees, calling the wars "Obama wars". The slow growth of the economy in the first two years of the Obama administration has led Republicans to call for a return to tax cuts for the richest one percent and deregulation of the oil and banking industries as the best way to solve the financial crisis. Obama's popularity has steadily fellen,[107] as the critical elements of his 2008 coalition slackened in their enthusiasm, especially young voters and independents.

Tea Party

A new element was the Tea Party Movement of 2009-10, a populist grass-roots movement comprising over 600 local units angry at the government and at both major parties.[108] Many units have promoted activism and protests.[109] The stated purpose of the movement has been to stop what it views as wasteful government spending, excessive taxation, and strangulation of the economy through regulatory bureaucracies. The Tea Party attracted national attention when it propelled Republican Scott Brown to a stunning victory in Senate election for the Massachusetts seat held by the Kennedy brothers for nearly 60 years.[110] In 2010 Tea Party candidates upset establishment Republicans in several primaries, such as Alaska, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Nevada, New York, South Carolina, and Utah, giving a new momentum to the conservative cause in the 2010 elections, and boosting Sarah Palin's visibility. Rasmussen and Schoen (2010) conclude that "She is the symbolic leader of the movement, and more than anyone else has helped to shape it."[111] In the fall 2010 elections, the New York Times has identified 129 House candidates with significant Tea Party support, as well as 9 running for the Senate; all are Republicans, as the Tea Party has not been active among Democrats.[112]

House Republicans, optimistic about regaining control, announced "A Pledge to America," in Sept. 2010. It called for permanent extension of all the Bush tax cuts, including those on the wealthy; cancellation of $250 billion in unspent stimulus money, and repeal of the Obama health care bill, replacing it with conservative proposals, including limits on malpractice lawsuits.[113]

The Tea Party itself is a conglomerate of conservatives with diverse viewpoints including libertarians and social conservatives. Most Tea Party supporters self-identify as "angry at the government".[114][115][116] One survey found that Tea Party supporters in particular distinguish themselves from general Republican attitudes on social issues such as gay marriage, abortion and immigration, as well as global warming.[117] However, discussion of abortion and gay rights has also been downplayed by Tea Party leadership.[118] In the lead up to the 2010 election, most Tea Party candidates have focused on federal spending and deficits, with little focus on foreign policy.[119]

Noting the lack of central organization or explicit spokesmen, Matthew Continetti of The Weekly Standard has said: "There is no single Tea Party. The name is an umbrella that encompasses many different groups. Under this umbrella, you’ll find everyone from the woolly fringe to Ron Paul supporters, from Americans for Prosperity to religious conservatives, independents, and citizens who never have been active in politics before. The umbrella is gigantic."[120]

As the editors of the Gallup Poll said, "in addition to conservatives being more enthusiastic than liberals about voting in this year’s election, their relative advantage on enthusiasm is much greater than we've seen in the recent past."[121]

Types

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2010) |

In the United States today, the word "conservative" is often used very differently from the way the word was used in the past and still is used in many parts of the world. The Americans after 1776 rejected the core ideals of European conservatism, based on the landed aristocracy, the established church, and the powerful, prestigious army.

Barry Goldwater in the 1960s spoke for a "free enterprise" conservatism. Jerry Falwell in the 1980s preached traditional moral and religious social values. It was Reagan's challenge to form these groups into an electoral coalition.[citation needed]

In the 21st century U.S., some of the groups calling themselves "conservative" include:

- Traditionalist conservatism — Opposition to rapid change in governmental and societal institutions. This kind of conservatism is anti-ideological insofar as it emphasizes means (slow change) over ends (any particular form of government). To the traditionalist, whether one arrives at a right- or left-wing government is less important than whether change is effected through rule of law rather than through revolution and sudden innovation.

- Christian conservatism — Conservative Christians are primarily interested in family values. Some preach that the United States was founded as a Christian nation; all believe that abortion is wrong; many favor teacher-led prayer in state schools; most are against homosexuality and define marriage as between one man and one woman. Most attack the profanity and sexuality in the media and movies.

- Limited government conservatism — Limited government conservatives look for a decreased role of the federal government. They follow Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in their suspicion of a powerful federal government.

- Neoconservatism — A modern form of conservatism that supports a more assertive, interventionist foreign policy, aimed at promoting democracy abroad. It is tolerant of an activist government at home, but is focused mostly on international affairs. Neoconservatism was first described by a group of disaffected liberals, and thus Irving Kristol, usually credited as its intellectual progenitor, defined a neoconservative as "a liberal who was mugged by reality." Although originally regarded as an approach to domestic policy (the founding instrument of the movement, Kristol's The Public Interest periodical, did not even cover foreign affairs), through the influence of figures like Dick Cheney, Robert Kagan, Richard Perle, Kenneth Adelman and (Irving's son) Bill Kristol, it has become most famous for its association with the foreign policy of the George W. Bush administration. Many of the nation's most prominent and influential conservatives during the two terms of the Bush administration were considered "neoconservative" in their ideological orientation.[122]

- Paleoconservatism — Arising in the 1980s in reaction to neoconservatism, stresses tradition, especially Christian tradition and the importance to society of the traditional family. Some, Samuel P. Huntington for example, argue that multiracial, multi-ethnic, and egalitarian states are inherently unstable.[123] Paleoconservatives are generally isolationist, and suspicious of foreign influence. The magazines Chronicles and The American Conservative are generally considered to be paleoconservative in nature.

- Libertarian conservatism or Fusionism — Emphasizes a strict interpretation of the Constitution, particularly with regard to federal power. Libertarian conservatism is constituted by a broad, sometimes conflicted, coalition including pro-business social moderates, those favoring classic states' rights, individual liberty activists, and many of those who place their socially liberal ideology ahead of their fiscal beliefs. This mode of thinking tends to espouse laissez-faire economics and a critical view of the federal government. Libertarian conservatives' emphasis on personal freedom often leads them to have social positions contrary to those of Christian conservatives. The libertarian branch of conservatism may have similar disputes that isolationist paleoconservatives would with neoconservatives. However libertarian conservatives may be more militarily interventionist or support a greater degree of military strength than other libertarians. Contrarily strong preference for local government puts libertarian conservatives in frequent opposition to international government.

Ideology and political philosophy

Classical conservatives tend to be anti-ideological, and some would even say anti-philosophical,[124] promoting rather, as Russell Kirk explains, a steady flow of "prescription and prejudice." Kirk's use of the word "prejudice" here is not intended to carry its contemporary pejorative connotation: a conservative himself, he believes that the inherited wisdom of the ages may be a better guide than apparently rational individual judgment.

In contrast to classical conservatism, social conservatism and fiscal conservatism are concerned with consequences as well as means.

There are two overlapping subgroups of social conservatives—the traditional and the religious. Traditional conservatives strongly support traditional codes of conduct, especially those they feel are threatened by social change. For example, traditional conservatives may oppose the use of female soldiers in combat. Religious conservatives focus on conducting society as prescribed by a religious authority or code. In the United States this translates into taking hard-line stances on moral issues, such as opposition to abortion and homosexuality. Some religious conservatives go so far as to support the use of government institutions to promote religiosity in public life.

Fiscal conservatives support limited government, limited taxation, and a balanced budget. Some admit the necessity of taxes, but hold that taxes should be low. A recent movement against the inheritance tax labels such a tax a death tax. Fiscal conservatives often argue that competition in the free market is more effective than the regulation of industry, with the exception of industries that exhibit market dominance or monopoly powers. For some this is a matter of principle, as it is for the libertarians and others influenced by thinkers such as Ludwig von Mises, who believed that government intervention in the economy is inevitably wasteful and inherently corrupt and immoral. For others, "free market economics" simply represents their belief that it is the most efficient way to promote economic growth: they support it not based on some moral principle, but pragmatically, because they hold that it just "works."

Most modern American fiscal conservatives accept some social spending programs not specifically delineated in the Constitution. As such, fiscal conservatism today exists somewhere between classical conservatism and contemporary consequentialist political philosophies.

Throughout much of the 20th century, one of the primary forces uniting the occasionally disparate strands of conservatism, and uniting conservatives with their liberal and socialist opponents, was opposition to communism, which was seen not only as an enemy of the traditional order, but also the enemy of western freedom and democracy. Thus it was the British Labour government—which embraced socialism—that pushed the Truman administration in 1945-47 to take a strong stand against Soviet Communism.[125] In the 1980s, the United States government spent billions of dollars arming and supporting Islamic terrorists, because these terrorists were fighting communists.[126]

Social conservatism and tradition

Social conservatism is generally dominated by defense of traditional social norms and values, of local customs and of societal evolution, rather than social upheaval, though the distinction is not absolute. Often based upon religion, modern cultural conservatives, in contrast to "small-government" conservatives and "states-rights" advocates, increasingly turn to the federal government to overrule the states in order to preserve educational and moral standards.

Social conservatives emphasize traditional views of social units such as the family, church, or locale. Social conservatives would typically define family in terms of local histories and tastes. Social conservatism may entail support for defining marriage as between a man and a woman (thereby banning gay marriage) and laws placing restrictions on abortion.

Fundamentalist Protestants, rejecting Darwinism, often advocate the teaching of intelligent design in the public schools, and believe that the theory of a God-created universe should be presented as a legitimate explanation for the world's creation.

Conservatives tend to strongly identify with American nationalism and patriotism. They denounce anti-war protesters and hail the police and the military. Conservatives hold that military institutions embody admirable values like honor, duty, courage, and loyalty. Military institutions are independent sources of tradition and ritual pageantry that conservatives tend to admire.

Some conservatives want to use federal power to block state actions they disapprove of. Thus in the 21st century came support for the "No Child Left Behind" program, support for a constitutional amendment prohibiting same-sex marriage, support for federal laws overruling states that attempt to legalize marijuana or assisted suicide or use eminent domain to take private property. The willingness to use federal power to intervene in state affairs is the negation of the old state's rights position.

Richard Hofstadter in 1966 claimed that opposition to conservatism has been common among intellectuals since about 1890.[127] In the 1920s, religious Fundamentalists like William Bell Riley and William Jennings Bryan (a liberal Democrat) led the battle against Darwinism and evolution, a battle which Fundamentalists are still fighting today. More recently the anti-intellectualism has taken the form of attacks on elites, experts, scientists, public schools and universities.[128]

Fiscal conservatism

Fiscal conservatism is the economic and political policy that advocates restraint of governmental taxation and expenditures. Fiscal conservatives since the 19th century have argued that debt is a device to corrupt politics; they argue that big spending ruins the morals of the people, and that a national debt creates a dangerous class of speculators. The argument in favor of balanced budgets is often coupled with a belief that government welfare programs should be narrowly tailored and that tax rates should be low, which implies relatively small government institutions.

This belief in small government combines with fiscal conservatism to produce a broader economic liberalism, which wishes to minimize government intervention in the economy. This amounts to support for laissez-faire economics. This economic liberalism borrows from two schools of thought: the classical liberals' pragmatism and the libertarian's notion of "rights." The classical liberal maintains that free markets work best, while the libertarian contends that free markets are the only ethical markets.

The economic philosophy of conservatives in the United States tends to be more liberal allowing for more economic freedom. Economic liberalism can go well beyond fiscal conservatism's concern for fiscal prudence, to a belief or principle that it is not prudent for governments to intervene in markets. It is also, sometimes, extended to a broader "small government" philosophy. Economic liberalism is associated with free-market, or laissez-faire economics.

Economic liberalism, insofar as it is ideological, owes its creation to the "classical liberal" tradition, in the vein of Adam Smith, Friedrich A. Hayek, Milton Friedman, and Ludwig von Mises.

Classical liberals and libertarians support free markets on moral, ideological grounds: principles of individual liberty morally dictate support for free markets. Supporters of the moral grounds for free markets include Ayn Rand and Ludwig von Mises. The liberal tradition is suspicious of government authority, and prefers individual choice, and hence tends to see capitalist economics as the preferable means of achieving economic ends.

Modern conservatives, on the other hand, derive support for free markets from practical grounds. Free markets, they argue, are the most productive markets. Thus the modern conservative supports free markets not out of necessity, but out of expedience. The support is not moral or ideological, but driven on the Burkean notion of prescription: what works best is what is right.

Another reason why conservatives support a smaller role for the government in the economy is the belief in the importance of the civil society. As noted by Alexis de Tocqueville, there is a belief that a bigger role of the government in the economy will make people feel less responsible for the society. These responsibilities would then need to be taken over by the government, requiring higher taxes. In his book Democracy in America, De Tocqueville describes this as "soft oppression."

It must be noted that while classical liberals and modern conservatives reached free markets through different means historically, to-date the lines have blurred. Rarely will a politician claim that free markets are "simply more productive" or "simply the right thing to do" but a combination of both. This blurring is very much a product of the merging of the classical liberal and modern conservative positions under the "umbrella" of the conservative movement.

The archetypal free-market conservative administrations of the late 20th century—the Margaret Thatcher government in Britain and the Ronald Reagan administration in the U.S. -- both held the unfettered operation of the market to be the cornerstone of contemporary modern conservatism (this philosophy is called neoliberalism by critics on the left). To that end, Thatcher privatized industries and public housing and Reagan cut the maximum capital gains tax from 28% to 20%, though in his second term he agreed to raise it back up to 28%. He wanted to increase defense spending and achieved that; liberal Democrats blocked his efforts to cut domestic spending.[129] Reagan did not control the rapid increase in federal government spending, or reduce the deficit, but his record looks better when expressed as a percent of the gross domestic product. Federal revenues as a percent of the GDP fell from 19.6% in 1981 when Reagan took office to 18.3% in 1989 when he left. Federal spending fell slightly from 22.2% of the GDP to 21.2%. This contrasts with statistics from 2004, when government spending was rising more rapidly than it had in decades.[130]

Electoral politics

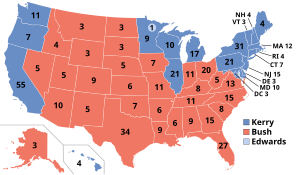

In the United States, the Republican Party is generally considered to be the party of conservatism. This has been the case since the 1960s, when the conservative wing of that party consolidated its hold, causing it to shift permanently to the right of the Democratic Party. The most dramatic realignment was the white South, which moved from 3-1 Democratic to 3-1 Republican between 1960 and 2000.

In addition, some United States libertarians, in the Libertarian Party and even some in the Republican Party, see themselves as conservative, even though they advocate significant economic and social changes – for instance, further dismantling the welfare system or liberalizing drug policy. They see these as conservative policies because they conform to the spirit of individual liberty that they consider to be a traditional American value.

On the other end of the scale, some Americans see themselves as conservative while not being supporters of free market policies. These people generally favor protectionist trade policies and government intervention in the market to preserve American jobs. Many of these conservatives were originally supporters of neoliberalism[131] who changed their stance after perceiving that countries such as China were benefiting from that system at the expense of American production. However, despite their support for protectionism, they still tend to favor other elements of free market philosophy, such as low taxes, limited government and balanced budgets.

Geography

Geographically the South, the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountain states, and Alaska are conservative strongholds. The "Left Coast" (California, Oregon, Washington), and the Northeast are liberal strongholds, albeit with some pockets of conservative strength. Conservatives are strongest in rural areas and, to a lesser extent, in the "exurbs" or suburbs. Voters in the urban cores of large metropolitan areas are much more liberal and Democratic. Thus, within each state, there is a division between urban, suburban, exurban, and rural areas.[132][133]

Other topics

Kirk's six canons of conservatism

Russell Kirk developed six "canons" of conservatism, which Gerald J. Russello described as follows:

- A belief in a transcendent order, which Kirk described variously as based in tradition, divine revelation, or natural law;

- An affection for the "variety and mystery" of human existence;

- A conviction that society requires orders and classes that emphasize "natural" distinctions;

- A belief that property and freedom are closely linked;

- A faith in custom, convention, and prescription, and

- A recognition that innovation must be tied to existing traditions and customs, which entails a respect for the political value of prudence.[134]

Kirk said that Christianity and Western Civilization are "unimaginable apart from one another."[135] and that "all culture arises out of religion. When religious faith decays, culture must decline, though often seeming to flourish for a space after the religion which has nourished it has sunk into disbelief."[136]

Courts

One stream of conservatism exemplified by William Howard Taft extols independent judges as experts in fairness and the final arbiters of the Constitution. However, another more critical variant of conservatism condemns "judicial activism: that is, judges using their decisions to control policy. This position goes back to Jefferson's vehement attacks on federal judges and to Abraham Lincoln's attacks on the Dred Scott decision of 1857.

In 1910 Theodore Roosevelt broke with most of his lawyer friends and called for popular votes that could overturn unwelcome decisions by state courts. President Franklin D. Roosevelt did not attack the Supreme Court directly in 1937, but ignited a firestorm of protest by a proposal to add seven new justices. The Warren Court of the 1960s came under conservative attack for decisions regarding redistricting, desegregation, and the rights of those accused of crimes.

A more recent variant that emerged in the 1970s is "originalism", the assertion that the United States Constitution should be interpreted to the maximum extent possible in the light of what it meant when it was adopted. Originalism should not be confused with a similar conservative ideology, strict constructionism, which deals with the interpretation of the Constitution as written, but not necessarily within the context of the time when it was adopted. In modern times, originalism has been advocated by U.S. Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia, former U.S. federal judge Robert Bork and other conservative jurists.

Semantics, language, and media

Language

Democrat Party

In the late 20th century conservatives found new ways to use language and the media to support their goals and to shape the vocabulary of political discourse. Thus the use of "Democrat" as an adjective, as in "Democrat Party" was used first in the 1930s by Republicans to criticize large urban Democratic machines. Republican leader Harold Stassen stated in 1940, "I emphasized that the party controlled in large measure at that time by Hague in New Jersey, Pendergast in Missouri and Kelly Nash in Chicago should not be called a 'Democratic Party.' It should be called the 'Democrat party.'"[137]

In 1947 Senator Robert A. Taft said, "Nor can we expect any other policy from any Democrat Party or any Democrat President under present day conditions. They cannot possibly win an election solely through the support of the solid South, and yet their political strategists believe the Southern Democrat Party will not break away no matter how radical the allies imposed upon it".[138] The use of "Democrat" as an adjective is standard practice in Republican national platforms (since 1948), and was a standard practice in the White House in 2001–2008, for press releases and speeches.

Socialism

Since the late 19th century "socialism" (or "creeping socialism") is often used as an epithet by conservatives to attack liberal spending or tax programs that enlarge the role of the government. In this sense it has little to do with government ownership of the means of production, or the various Socialist parties. Thus William Allen White attacked presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan in 1896 by warning that, "The election will sustain Americanism or it will plant Socialism."[139][140]

Radio

Conservatives gained a major new communications medium with the resurgence of talk radio in the late-1980s. Rush Limbaugh proved there was a huge nationwide audience for specific and heated discussions of current events from a conservative viewpoint. Major hosts who describe themselves as conservative include: Michael Peroutka, Jim Quinn, Dennis Miller, Ben Ferguson, William Bennett, Lars Larson, Sean Hannity, G. Gordon Liddy, Laura Ingraham, Mike Church, Glenn Beck, Mark Levin, Michael Savage, Kim Peterson, Michael Reagan, Jason Lewis and Ken Hamblin.[citation needed] The Salem Radio Network syndicates a group of religiously-oriented Republican activists, including Evangelical Christian Hugh Hewitt, and Jewish conservatives Dennis Prager and Michael Medved. One popular Jewish conservative, Dr. Laura Schlessinger, offers parental and personal advice, but is an outspoken critic of social and political issues.

Talk radio provided an immediacy and a high degree of emotionalism that seldom is reached on television or in magazines. Pew researchers found in 2004 that 17% of the public regularly listens to talk radio. This audience is mostly male, middle-aged, well-educated and conservative. Among those who regularly listen to talk radio, 41% are Republicans and 28% are Democrats. Moreover, 45% describe themselves as conservatives, compared with 18% who say they are liberal.[141]

Academic analysis

Academic discussion of conservatism in the United States has been dominated by American exceptionalism, the theory that British conservatism has little or no relevance to American traditions. This is in contrast to the view that Burkean conservatism has a set of universal principals which can be applied all societies.[142] According to Louis Hartz, because the United States skipped the feudal stage of history, the American community was united by liberal principles,[143] and the conflict between the "Whig" and "democrat" traditions were conflicts within a liberal framework.[144] In this view, what is called conservatism in America is not European conservatism but rather classical liberalism.[145] A differing view is found in Russell Kirk's The Conservative Mind. Kirk wrote that the American Revolution was "a conservative reaction, in the English political tradition, against royal innovation".[24] Kirk's theories were severely criticized by M. Morton Auerbach in The Conservative Illusion.[146] Theodore Adorno and Richard Hofstader referred to modern American conservatives as "pseudo-conservatives", because of their "dissatisfaction with American life, traditions and institutions" and because they had "little in common with the temperate and compromising spirit of true conservatism".[147]

Thinkers and leaders

Major American conservatives

Rossiter's giants

Clinton Rossiter, a leading expert on American political history, published his history of Conservatism in America and also a summary article on "The Giants Of American Conservatism" in American Heritage.[148] His goal was to identify the "great men who did conservative deeds, thought conservative thoughts, practiced conservative virtues, and stood for conservative principles." To Rossiter, conservatism was defined by the rule of the upper class. He wrote, "The Right of these freewheeling decades was a genuine Right: it was led by the rich and well-placed; it was skeptical of popular government; it was opposed to all parties, unions, leagues, or other movements that sought to invade its positions of power and profit; it was politically, socially, and culturally anti-radical." His "giants of American conservatism" were: John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, John Marshall, Daniel Webster, John C. Calhoun, Elihu Root, and Theodore Roosevelt. He added that Washington and Lincoln transcend the usual categories, but that conservatives "may argue with some conviction that Washington and Lincoln can also be added to his list."

Rossiter went to note the importance of other conservative leaders over the past two centuries. Among the fathers of the Constitution, which he calls "a triumph of conservative statesmanship," Rossiter said conservatives may "take special pride" in James Madison, James Wilson, Roger Sherman, John Dickinson, Gouverneur Morris and the Pinckneys of South Carolina. For the early 19th century, Rossiter said the libertarians and constitutionalists who deserve the conservative spotlight for their fight against Jacksonian Democracy include Joseph Story and Josiah Quincy in Massachusetts; Chancellor James Kent in New York; James Madison, James Monroe, and John Randolph of Roanoke in Virginia.