Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science: Difference between revisions

| Line 401: | Line 401: | ||

Does that mean it is somewhat radioactive? [[Special:Contributions/92.29.112.73|92.29.112.73]] ([[User talk:92.29.112.73|talk]]) 13:18, 11 November 2010 (UTC) |

Does that mean it is somewhat radioactive? [[Special:Contributions/92.29.112.73|92.29.112.73]] ([[User talk:92.29.112.73|talk]]) 13:18, 11 November 2010 (UTC) |

||

:No. [[User:Shoy|shoy]] <small>([[User talk:Shoy|reactions]])</small> 14:30, 11 November 2010 (UTC) |

:No. [[User:Shoy|shoy]] <small>([[User talk:Shoy|reactions]])</small> 14:30, 11 November 2010 (UTC) |

||

Terse. Helpful. [[Special:Contributions/92.29.112.73|92.29.112.73]] ([[User talk:92.29.112.73|talk]]) 14:41, 11 November 2010 (UTC) |

|||

== Particles and antiparticles - two directions of time == |

== Particles and antiparticles - two directions of time == |

||

Revision as of 14:41, 11 November 2010

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

November 7

Beyond us

Are the problems in the world simply beyond us? Poverty, AIDS, human rights abuses, war. I am just wondering if that is what people learn as they try to accomplish things with a futility. Perhaps this should go in the misc section, but I was thinking that science should have the answer, above all things, right? AdbMonkey (talk) 00:22, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- It remains to be seen, AdbMonkey. We are awaiting the empirical results on that. Your last question reminds me of something I heard on NPR the other day, I'll see if I can dig that up for you in a moment... WikiDao ☯ (talk) 00:38, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- All you mention are problems we ourselves have created. The real question is, do we have the will to undo them? Perhaps we should start with renaming everyone's "defense" department back to their "department of war." Unfortunately, from war to pharmaceuticals, all is driven by the quest for profits. Unless of course you're just power hungry. Not to mention that the last "politician" I can think of where that moniker was not a dirty word was (for me in the U.S.) Hubert Humphrey. PЄTЄRS

JVЄСRUМВА ►TALK 01:56, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- All you mention are problems we ourselves have created. The real question is, do we have the will to undo them? Perhaps we should start with renaming everyone's "defense" department back to their "department of war." Unfortunately, from war to pharmaceuticals, all is driven by the quest for profits. Unless of course you're just power hungry. Not to mention that the last "politician" I can think of where that moniker was not a dirty word was (for me in the U.S.) Hubert Humphrey. PЄTЄRS

- (e/c) Okay, that was a discussion on "Science and Morality" with Steven Pinker, Sam Harris,Simon Blackburn, and Lawrence Krauss. The lead-in to the program is:

So far, I have only heard about the first 15 minutes of the program myself. But it may be relevant. If so, I'll comment further after having listened to the rest of it. :) Regards, WikiDao ☯ (talk) 02:10, 7 November 2010 (UTC)"Did we evolve our sense of right and wrong, just like our opposable thumbs? Could scientific research ever turn up new facts to resolve sticky moral arguments such as euthanasia, or gay marriage? In this hour of Science Friday, we'll talk with philosophers and scientists about the origins of human values. Our guests are participating in an international conference entitled “The Origins of Morality: Evolution, Neuroscience and Their Implications (if Any) for Normative Ethics and Meta-ethics” being held in Tempe, Arizona on November 5-7. Listen in to their debate, and share your thoughts."

- To the OP: Not at all. Instead of comparing the current world to an ideal perfect world, without any form of suffering, instead compare today's world to that of say 50 years ago. Or 100 years ago. Or 200 years ago. Or 1000 years ago. At any point in history any arbitrarily long distance in the past, there were a higher proportion of people who were abjectly poor, or diseased, or who died young, or any other number of miserable existences. We've known about AIDS for about 30 years. Smallpox and Plague we knew about for centuries before they were finally cured. Give it time. It only seems like things are bad because you are living through them. Things were infinitely shittier before you were born. --Jayron32 03:23, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- That's a good point, and a good way of putting it. But, Jayron, the world is today in arguably a fundamentally different position than at any previous time with regard to humanity and its impacts on itself (overpopulation, technology, etc) and the world in general (environmentally, etc). It's a complex system, and as it gets more complex it gets more difficult to tell what's going to happen next... WikiDao ☯ (talk) 03:47, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- I'm not so sure about that. Ever since people began living in cities, they have been creating problems for themselves that living in caves did not. As bad as pollution was at the height of the Industrial Revolution, it still didn't cause as much death and illness as something as plainly simple as not shitting in the middle of the street. Progress tends to, on the balance, result in a higher standard of living across the board. It is true that technology and advancement causes unique problems, but it solves more problems than it causes. Despite the problems with polution, the Industrial Revolution in the UK saw the greatest population explosion that country ever saw. And as the modern economy has evolved, polution has gotten better. Yes, it is still a problem, but not nearly the problem it was in the middle 1800s. Thomas Malthus's predictions haven't come true, because his assumption that food production growth would be linear doesn't hold up. Food production has kept up with population growth because of technological advancements. The only major problems with overpopulation are politically created; its not that the food doesn't exist to feed people, or that the technology doesn't exist to fix the problems of overpopulation, its just that the political will to actually fix the problems lags behind the technological advancements. But that has always been so, and what has also always been so is that it eventually catches up. --Jayron32 03:59, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Okay, sure, and if it does work out for humanity (and we ought to find out within the next century or so -- if we get through the tail-end here of the population explosion that has gone hand-in-hand with technological and social progress, it'll happen or not within the next hundred years) – if it does work out, it will be because it is as you describe it. I take your points about cities and failed Malthusian expectations. Still, we are globally overpopulated now. It's a closed complex system, and we've run up against the boundaries. What happens in a petri-dish when the bacteria run out of nutrients and fill it with their waste-products...? WikiDao ☯ (talk) 04:16, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Actually, technological and social progress tends to lead to LOWER population growth, not more. See Demographic-economic paradox, aka The Paradox of Prosperity. In highly developed nations, like most of Western Europe and North America, the birth rate is below replacement rate, and these nations have to import workers from less developed nations just to do all of the work that the kids they aren't having aren't doing. The real question is what is going to happen to the world when EVERY country is so developed that we're all operating at below replacement rate. The trend would indicate that we're going to have the OPPOSITE of a Malthusian catastrophe, in that as we become more advanced, we don't even have enough kids to maintain a steady population. --Jayron32 04:24, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Okay, sure, and if it does work out for humanity (and we ought to find out within the next century or so -- if we get through the tail-end here of the population explosion that has gone hand-in-hand with technological and social progress, it'll happen or not within the next hundred years) – if it does work out, it will be because it is as you describe it. I take your points about cities and failed Malthusian expectations. Still, we are globally overpopulated now. It's a closed complex system, and we've run up against the boundaries. What happens in a petri-dish when the bacteria run out of nutrients and fill it with their waste-products...? WikiDao ☯ (talk) 04:16, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- I'm not so sure about that. Ever since people began living in cities, they have been creating problems for themselves that living in caves did not. As bad as pollution was at the height of the Industrial Revolution, it still didn't cause as much death and illness as something as plainly simple as not shitting in the middle of the street. Progress tends to, on the balance, result in a higher standard of living across the board. It is true that technology and advancement causes unique problems, but it solves more problems than it causes. Despite the problems with polution, the Industrial Revolution in the UK saw the greatest population explosion that country ever saw. And as the modern economy has evolved, polution has gotten better. Yes, it is still a problem, but not nearly the problem it was in the middle 1800s. Thomas Malthus's predictions haven't come true, because his assumption that food production growth would be linear doesn't hold up. Food production has kept up with population growth because of technological advancements. The only major problems with overpopulation are politically created; its not that the food doesn't exist to feed people, or that the technology doesn't exist to fix the problems of overpopulation, its just that the political will to actually fix the problems lags behind the technological advancements. But that has always been so, and what has also always been so is that it eventually catches up. --Jayron32 03:59, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- That's a good point, and a good way of putting it. But, Jayron, the world is today in arguably a fundamentally different position than at any previous time with regard to humanity and its impacts on itself (overpopulation, technology, etc) and the world in general (environmentally, etc). It's a complex system, and as it gets more complex it gets more difficult to tell what's going to happen next... WikiDao ☯ (talk) 03:47, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

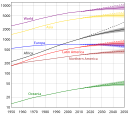

- Yes. We are aiming for something like the diagram (of a sigmoid curve) shown at the left. That region on the upper-right-hand side is the region we are just entering now (see the diagram on the right and the World Population article, which says, "In the 20th century, the world saw the biggest increase in its population in human history due to lessening of the mortality rate in many countries due to medical advances and massive increase in agricultural productivity attributed to the Green Revolution," which is one of the things I was saying, too). WikiDao ☯ (talk) 04:36, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

Ah, it's he or she of the very funny user page, again! Hi, User:AdbMonkey! You might like to have a look at The Revolution of Hope, by the sociologist Erich Fromm. In one of his books, The Sane Society, I think it was, he makes a case, based on sociological metrics like suicide rates, alcoholism incidence, etc. for the idea that current Western society is more screwed up than it ever has been before. I've never seen his numbers discussed anywhere else, but (as I recall, it's been ten or twenty years) he claims the occurrence of such signs of distress is astronomically higher than ever before in recorded history. He's of the opinion that our technological development has way, way outstripped our moral intelligence, that we're like toddlers who think we can use fire responsibly because we know how to start one. ( I agree with this assessment, FWIW; it seems obvious to me. ) Along that same line, Fromm points out that if something can be done with technology, then eventually it almost certainly will be done, by someone, somewhere in the world; in this way technology has it's own inertia that sweeps us all along without much conscious choice or deliberation about whether the changes it introduces are what we really want, how we really want to live on the Earth. This is no way to run a planet, in Fromm's view. ;-) Then, in The Revolution of Hope (subtitled, "Toward a humanized technology") he gives one part of his "prescription" for what ails us as a people. Good fun, his ideas stretch the intellect, imo. Best, – OhioStandard (talk) 04:36, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Take a look at Malthusian catastrophe, The World Without Us, tipping point (sociology), philosophy of war, transhumanism, evolution of evolution and neuroplasticity. ~AH1(TCU) 17:02, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

Thanks WikiDao. I have listened to some lectures by Pinker before. I'm not sure how he would answer the question. Thanks Jayron, for your way to reframe how I look at the world. Ohiostandard, you kill me. I was really wondering if there perhaps is a large school of once do-gooders, who have simply become jaded with trying to effectuate positive change (please no questions of how do we define positive and negative). I was just wondering if perhaps there was an ascribed term to this besides just "went through a green phase" or "became jaded" or "grew up and realized how the world worked." I hope I am making sense? I'm think specifically of a young person who is excited and hopeful and eager to make a positive change in the world, or help build schools, or volunteer with Medicans sans Frontieres, but they get weighed down and burnt out after awhile, when they see that their efforts don't make the dent they were hoping for. I was just wondering if older people has any wisdom about this, or if anyone knew any books about how to prevent this feeling of hopelessness, if there was a psychological scientific name for this, or if simply falls into the realm of motivational speaking. I hope I am making sense. AdbMonkey (talk) 19:31, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Creeping nihilism? I say the best way to deal with it is to just stare it down. (You have nothing to lose by the attempt, right?;) WikiDao ☯ (talk) 19:59, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

Dear Wikidao. Is that all it is? I thought nihilism was when an anarchist destroyed everything. I just thought maybe there was German term for this or something. I like you, wikidao. You're very dao about things, and that is so nice. Even your name is cute, because it has wiki and dao put together in it. Ok, well I know this isn't supposed to be socially jabbered up with public declarations or odes to other users, but I just couldn't help telling you how I like the cutseyness of your name. (If you meant it to come across like a strong, karate kicking ninja, I apologize.) So yeah, thanks for that NPR link AdbMonkey (talk) 04:34, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Well I'm flattered and all, I'm sure, monkey, but this really is not the place - I'll respond more to all that on your talk page. :)

- So nihilism isn't really what you were describing? I realize the word has an "anarchist" feel to it, but didn't mean to suggest that aspect of it. And I wasn't really sure, just guessing (note the question mark there, after "Creeping nihilism?"). You don't mean just "disillusionment", though, right? So you are thinking of a "German term", then? I'm sure there must be one, perhaps someone else will get it. Regards, WikiDao ☯ (talk) 05:07, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

magazine

can u buy famous older issues directly from playboy? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Kj650 (talk • contribs) 01:59, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- This is science? Anyway, the Playboy store only has some issues available from the 1980s forward, plus a reproduction of the Marilyn Monroe one. Clarityfiend (talk) 03:34, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Well, it's definitely falsifiable ... 63.17.41.3 (talk) 03:59, 10 November 2010 (UTC)

- IIRC, Playboy's website has digitized versions of every issue ever produced, so you can at least access it if you pay the subscription fee. There are other magazines which offer free digital versions of their back issues. Sports Illustrated has a full collection of scanned issues (not just text, but full digital scans of every page of every magazine) going back to their first issue, and it is entirely free to browse. It's also fully text searchable. --Jayron32 04:28, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Interesting. The Playboy Archive lets you [cough, cough] "read" 53 back issues for free. And Jayron is correct; apparently you can get digital versions for each decade.[1] Clarityfiend (talk) 04:57, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

pollution question

How much chemical does it take for the environment to be labeled as contaminated? Is it the same for every chemical? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 75.138.217.43 (talk) 02:04, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- It's different. I assume it's related to how toxic the chemical is, how well the environment can handle it, and how long it takes for it to be biodegraded. For example oil in the gulf is not as big a problem as it would be near alaska. The gulf has lots of mechanisms to deal with oil (bacteria, warmth, etc), alaska doesn't. Salt would not be a problem near the ocean, but would be near the great lakes. Ariel. (talk) 02:21, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- I do have to respond to this by saying that everything in the environment is made entirely of chemicals. So, it's obviously not the same for every chemical. I'm guessing our questioner is referring to chemicals widely regards as pollutants, and the same is true for them. ANother perspective is that what is good for some plants will be deadly for others. So, huge variation. HiLo48 (talk) 03:58, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

Electronics/Physics question about laptop power supplies

Hi, all. Can any electronics/physics guru tell me what's likely to happen if I plug a newish Gateway laptop into mains via an old AC/DC power converter "brick" that's from a (much earlier, monochrome screen) Gateway laptop?

Specs for the converter/brick that came with the new laptop are DC Output 19V, 3.42 Amps, according to a label affixed to it. There's also a symbol between the "Volts" number and the "Amps" number that consists of a short, horizontal line with a parallel dashed line (in three segments) positioned just below it. I presume this has to do with the polarity of the bayonet-style connection jack that plugs in to the laptop? That jack is also represented figuratively by the familiar "two concentric rings" graphic that shows that its "negative" pole is on the periphery/outside of the jack, with the "positive" pole located at the center. A label on the bottom of the new laptop also says 19 Volts and 3.42 Amps, btw. The old converter/brick has the same parallel lines symbol as the new one, but no "concentric rings" graphic, and a legend that says it's specified to deliver 19 Volts and just 2.64 Amps. This would seem to mean that the "new" power supply is capable of delivering 30% more current at 19 Volts than the "old" one can, also at 19 Volts, right?

So if I try this, is something likely to melt, and if so, what? The power supply? The computer? Or might everything still be within tolerance? I could try it with the laptop battery installed and fully charged, of course; would that be safer in case the power supply fries? And if this would be a really dumb thing to attempt, would it be sufficiently less dumb if I were to try running the new laptop only in some very low-power mode while connected to mains via the old converter/brick?

No penalty for informed guessing: I probably won't try this, regardless of the advice I get here. But I'll formally state that, as an adult, I alone am responsible for the consequences of my actions. That means I won't blame anyone else if I try this and it disrupts the fabric of the space-time continum, sets my house on fire, or worse, fries my computer. If anyone wants to explain the physics of what's likely to happen, I'd be interested to know that, too, since that's at least half my interest in asking this question. Thanks! – OhioStandard (talk) 04:04, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Well, we don't yet have a guideline against answering disrupting-the-fabric-of-the-space-time-continuum advice questions so... ;) The solid-and-dashed-line symbol is a well-known symbol for DC. The AC symbol is a sine wave. It is 99% likely that the polarity of your DC output hasn't changed (keep in mind that 83% of statistics are made up on the spot). It is very rare that the "shield" (outer-most parts) of a device/plug is NOT designed to be the ground/earth/negative terminal. As to what could happen if you plugged it in...it depends. If your old power supply has overload protection built-in it might switch itself off if you try to draw too much current. Or it might just run a bit hotter than normal. Or it might overheat, melt something internally and catch alight. Either way using a full battery would lessen the current draw when you plugged it in. Note that even though the power supply is rated for X amps, it doesn't mean that the laptop draws X amps. It is likely that the power supply is over-designed by at least 10% compared to the maximum laptop draw current. YMMV. Regards, Zunaid 05:44, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks, Zunaid! That's the word I was reaching for, "overdesigned". I was wondering if the old power supply might be sufficiently overdesigned to allow the swap; good word. The laptop itself does have a sticker affixed to it that says 19 V and 3.42 A, just like the power supply that shipped with it, but I understand that may not mean much. E.g. maybe it only draws that high a current when bluetooth power is on, there's three PC cards inserted, it's ethernet circuits are busy, the DVD writer is writing, etc. etc., i.e. when the computer is operating at maximum load.

- But can you also give me some feeling for what would happen, in terms of the relevant physics equations, if such a state occurred when I was using the old (2.64 A) power supply? In terms, for example, of Ohm's Law? Voltage is fixed, right? So if you start adding "loads" (fire up the DVD burner, turn on wireless networking, etc.) that does what, increase the overall resistance? ( Can you tell I'm no prodigy re this stuff? ;-) If that's correct, then ... Well, then I'm out to sea, I'm afraid. But I have the vaguely formed idea that one of the three Ohm's Law variables will somehow become too extreme, and bad things might happen.

- I guess besides just knowing I could damage hardware, I'm also trying to get some glimpse about how the dynamic interaction of those variables might change with increasing load, how different parts and subsystems (or even running software routines?) might be adversely affected when one of those variables deviates too far outside normal limits. I know there's no unified, simple answer for all cases like this, but am I at least thinking of this at all correctly? What, for example, would happen in an exagerated instance similar to this case. What if I hooked up my "19 V, 3.42 A" laptop to a "19 V, 0.5 A" power supply? Apart from the smoke billowing from the power supply or the hard drive spinning at one-third of its normal speed (just kidding), is there any way to know what would be going on re the variables of Ohm's Law? Any way, from just the relevant equations, to demonstrate on paper why doing so would be bad? I could hardly be more ignorant about electricity, I'm afraid, but I'd like to be able to understand, just from formulae, if possible, what happens when a device "wants" to draw more current than a power supply can deliver. – OhioStandard (talk) 06:43, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Modern power supplies are Switch-mode power supplies with circuitry much more complex than simple Ohm's-law calculations, but the article doesn't say how they behave under overload conditions. My instinct is that they will just reduce the output voltage (and overheat slightly rather than bursting into flame), but I haven't run any tests to confirm or refute this claim. I have successfully run a laptop with the wrong power supply, but not under serious overload, and I wouldn't recommend the practice. Dbfirs 07:59, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- The key terms here are internal resistance and electrical power, the power supply has internal resistance (like a battery does - see the article) - and the power dissapated (as heat) is V2/R or I2R. For this it's probably easier to use the equation with I (current, amps) - try to draw 3.42A from a 0.5A supply and you will be generating

about 7over 40 times as much heat - hence it gets hot - and possibly breaks. There's more detail and explanation on this if asked. using the V2/R equation is more complicated than it seems because the power supply switches on and off - in short V is not 19V, but a higher voltage in pulses- actually the relationship between current and heat given off in the power supply is not quite the same as the example above .. in fact the heat will be about proportional to the current for your example (because of the way SMPSs work) - which means about 7 times in the above example.Sf5xeplus (talk) 08:58, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- In practice the power supply will have some sort of overload protection built in (probably by law). I'm not so sure that it would reduce the voltage as suggested by dbfirs above, but it might. What I'd guess is that it either a. detects that the current is over the maximum rated (using a hall effect sensor) and/or detects when the device gets to hot (temperature sensor) - and then shuts off.

- Note if the power supply is an old transformer (heavy) type the situation is a bit different.Sf5xeplus (talk) 08:24, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Oh. - it's the power supply that is likely to melt, not the computer - though if the computer is run using a lower voltage than designed it may work, but there is an increasing likelyhood of the processor malfunctioning (not a permanent effect - just a crash as it freezes up or gets its sums wrong..)Sf5xeplus (talk) 08:47, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- You could well be correct about not reducing the voltage on overload. It was the old transformer-type supplies that behaved in that way. Surely someone has investigated the behaviour of modern supplies under overload? Do they just switch off? I haven't time to do the experiment just now. Dbfirs 10:30, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- The key terms here are internal resistance and electrical power, the power supply has internal resistance (like a battery does - see the article) - and the power dissapated (as heat) is V2/R or I2R. For this it's probably easier to use the equation with I (current, amps) - try to draw 3.42A from a 0.5A supply and you will be generating

- Thanks, Dbfirs! Thanks Sf5xeplus! I appreciate your comments on this. So the likelihood seems to be that a modern power supply would probably have some variety of overlimit mechanism that would implement a non-catastrophic fail or suspension of current? Non-catastrophic to the connected computer, I mean, if not necessarily to the external power converter "brick" itself? – OhioStandard (talk) 04:57, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

Cholera treatment

Somewhere several years ago I heard that Gatorade would be almost ideal for treatment of Cholera (presumably used for rehydration). I haven't been able to find anything to confirm this since, though, so how plausible of an idea is this? Ks0stm (T•C•G) 04:11, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- According to the article you link, in the lead " The severity of the diarrhea and vomiting can lead to rapid dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Primary treatment is with oral or intravenous rehydration solutions." Presumably, in a pinch, Gatorade would work. From reading the article, it seems that the main problem with Cholera is the massive diarrhea and vomiting causes such rapid dehydration and electrolyte problems that that can kill you before your body has a chance to fight the infection. See also Oral rehydration therapy. --Jayron32 04:20, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Well my main question rephrased was basically whether Gatorade (or Powerade, etc) would be effective for oral rehydration when stricken with Cholera, due to such drinks having the water, salt, and electrolytes needed to replenish those lost during the infection, or if there is something that would prevent their overall effectiveness as a treatment. I already read the articles in question searching to see if it mentioned anything about such drinks, but didn't see anything. Ks0stm (T•C•G) 04:31, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- I had a long, speculative post written out, then I did the google search. Gatorade was first proposed as a Cholera treatment in 1969 in the New England Journal of Medicine, and you don't get a better reliable source than that. See this. You could also find a wealth of information at this google search or this similar one. --Jayron32 04:44, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Well my main question rephrased was basically whether Gatorade (or Powerade, etc) would be effective for oral rehydration when stricken with Cholera, due to such drinks having the water, salt, and electrolytes needed to replenish those lost during the infection, or if there is something that would prevent their overall effectiveness as a treatment. I already read the articles in question searching to see if it mentioned anything about such drinks, but didn't see anything. Ks0stm (T•C•G) 04:31, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Sodium secretion into the intestinal tract during a diarrheal illness is much greater than the typical losses you would expect in sweat from exercise. While sports drinks are fine for short-term replacement of fluid and electrolyte losses from sweating, the main reason you don't see those drinks being used widely for oral rehydration is that they simply don't have enough electrolytes to replace the severe losses from diarrheal illnesses. --- Medical geneticist (talk) 13:54, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Sports drinks are also more expensive to store and transport than the little packets of oral rehydration salts. I doubt there's much Gatorade in Haiti at the moment! Physchim62 (talk) 19:24, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Umm I've have a whole packet of solid gatorade crystals. "Just add water". John Riemann Soong (talk) 20:27, 10 November 2010 (UTC)

- Sports drinks are also more expensive to store and transport than the little packets of oral rehydration salts. I doubt there's much Gatorade in Haiti at the moment! Physchim62 (talk) 19:24, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

Is the age of the universe relative?

Thanksverymuch (talk) 04:31, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- You'll want to read the articles Age of the universe and Comoving distance and Proper frame. The quoted age of the universe is the age given for the earth's current frame of reference, extrapolated back to the point of the Big Bang. In other words, we assume the age of the Universe to be for the Earth's current frame of reference (relative speed and location). We assume the earth to be stationary (what is called the "proper frame") and make all measurments assuming that. In reality, nothing is stationary. In a different reference frame (i.e. if you were moving at a different speed than the earth is), the age would of course be different. This is due to the issues raised by special relativity and general relativity. --Jayron32 04:37, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks! What is the maximum possible relative age of the universe? Thanksverymuch (talk) 04:46, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- That's impossible to answer, because of the way that time works. There is no universal reference frame for which we can measure against; there is no absolute time. There are an infinite number of reference frames which one could conceive of in which the universe could be literally any age. We choose the earth's reference frame because that's the one we're in. This is not the same thing as saying that the Universe is infinite in age, its just that we could arbitrarily choose any reference frame in which the Universe could be any age. --Jayron32 04:53, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- For an object moving at (over very close to) the speed of light since the big bang, how old is another object moving at the slowest possible speed since the big bang? Thanksverymuch (talk) 05:01, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- For an object moving at the speed of light relative to what? --Jayron32 05:02, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- A stationary object. Thanksverymuch (talk) 05:09, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Stationary relative to what? --Jayron32 05:10, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Let me ask the question differently - is there a reference frame that entails an infinitely old universe? If not, just how old can the universe get? Thanksverymuch (talk) 05:20, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- There is no reference frame that entails an infinitely old universe. There are an infinite number of reference frames that entail an arbitrarily old universe. There is a distinction between infinite and arbitrarily large. In every reference frame, the universe is a finite age. But as the number of possible reference frames is boundless, for any age you could pick, there is a reference frame for which the universe is THAT age. Does that make sense? --Jayron32 05:23, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- I was unaware of this distinction. It does make sense. Thanksverymuch (talk) 05:40, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Actually, I was a little incorrect. The age of the universe is quoted not to Earth's reference frame, but to the reference frame of the Hubble flow, that is to the metric expansion of space. The universe is 13ish billion years old on that time frame. --Jayron32 05:30, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks for the clarification. Thanksverymuch (talk) 05:40, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- There is no reference frame that entails an infinitely old universe. There are an infinite number of reference frames that entail an arbitrarily old universe. There is a distinction between infinite and arbitrarily large. In every reference frame, the universe is a finite age. But as the number of possible reference frames is boundless, for any age you could pick, there is a reference frame for which the universe is THAT age. Does that make sense? --Jayron32 05:23, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Let me ask the question differently - is there a reference frame that entails an infinitely old universe? If not, just how old can the universe get? Thanksverymuch (talk) 05:20, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Stationary relative to what? --Jayron32 05:10, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- A stationary object. Thanksverymuch (talk) 05:09, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- For an object moving at the speed of light relative to what? --Jayron32 05:02, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- For an object moving at (over very close to) the speed of light since the big bang, how old is another object moving at the slowest possible speed since the big bang? Thanksverymuch (talk) 05:01, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- That's impossible to answer, because of the way that time works. There is no universal reference frame for which we can measure against; there is no absolute time. There are an infinite number of reference frames which one could conceive of in which the universe could be literally any age. We choose the earth's reference frame because that's the one we're in. This is not the same thing as saying that the Universe is infinite in age, its just that we could arbitrarily choose any reference frame in which the Universe could be any age. --Jayron32 04:53, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks! What is the maximum possible relative age of the universe? Thanksverymuch (talk) 04:46, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

I wander though, are there really an infinite number of reference frames? Are there an infinite number of speeds? Are there an infinite number of gravitational states? If the number of reference frames is finite, it may be possible to calculate an upper and low bound for the age of the universe, and even an average age. Thoughts? Thanksverymuch (talk) 13:47, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- See multiverse, Milky Way#Velocity and cutoff. ~AH1(TCU) 16:55, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

Jayron, are you sure that "for any age you could pick, there is a reference frame for which the universe is THAT age"? My knowledge of general relativity is somewhat sketchy, but surely in special relativity it makes sense to ask what the "maximum time" between two events is? There is always a frame in which the time between events is arbitrarily small, the observer's speed simpy has to be arbitrarily close to c. But at least in special relativity this doesn't work the other way around, and you can't find a frame in which the time between two events is arbitrarily large. What would the velocity of such a frame be? 213.49.88.236 (talk) 17:16, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, Jayron is incorrect about that; the usual quoted age of the universe is the maximum elapsed time from the big bang (and see this section for an explanation of what "big bang" means in this context). Also, the whole idea of using "reference frames" at cosmological scales is dubious. I don't like reference frames even in special relativity—I think they just interfere with understanding what the theory is about. But at least the term has an unambiguous meaning in special relativity. In general relativity it doesn't. -- BenRG (talk) 19:04, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Now I'm lost. Is the age of universe relative or not? Thanksverymuch (talk) 19:52, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

The measured age of the universe does indeed depend on how the age of the universe is measured. However, ignore everything else from above, and let's start from scratch. Imagine a bunch of little clocks that were created all over the universe shortly after the big bang. The clocks are basically running stopwatches, which are created with their time starting off at zero. At the time of their creation, the clocks are scattered every which way, with their initial velocities all completely independent of each other. Fast forward to now, when a bunch of those clocks are collected, and examined in a laboratory on Earth.

There's a kind of radiation called the cosmic microwave background radiation, that was created all over the universe a few hundred thousand years after the big bang, and which is still detectable today. If you're traveling at roughly the right velocity (which the Earth is pretty close to), that radiation looks very close to the same no matter which direction you look in. Consider a clock that’s been at that right velocity for essentially its whole life (call it a "comoving" clock), that's also spent essentially its whole life far away from any galaxies or any other kind of object. A clock like that will say that it's been ticking for roughly 13.7 billion years.

None of the other clocks collected will read a time more than that (roughly) 13.7 billion years, but some of them will read less. In particular, clocks that have spent a big chunk of their life moving very fast relative to nearby comoving clocks will read less time due to time dilation due to relative velocity, a phenomenon which can be described as "moving clocks run slow." In addition, clocks that have spent a big chunk of their life close to a massive body will read less time due to gravitational time dilation, i.e., due to the massive body bending spacetime in that area. In either case, the clocks running slow has nothing to do with how the clocks operate, but is purely a matter of how time works.

None of the clocks will show precisely zero elapsed time, but the time shown on the clocks could in principle be an arbitrarily small positive number. In practice, clocks couldn't be completely stopped due to time dilation due to relative velocity, because it'd take an infinite amount of energy to try to get the clock up to moving at the speed of light. And clocks couldn't be completely stopped due to gravitational time dilation, because that would require them to be at the center of a black hole, from which you wouldn't be able to retrieve the clock, and which the clock wouldn't survive, anyway.

The clocks could show any amount of elapsed time in between close to zero and the roughly 13.7 billion years, so there are an infinite number of different amounts of elapsed times that the clocks could show, because there are an infinite number of different real numbers within any finite range of real numbers. But the size of the range of possible different values on the clocks is about 13.7 billion years, which of course is a finite amount of time. Red Act (talk) 09:47, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks for this excellent clarification Red Act! So the answer is a definite YES - The age of the universe is relative.

- But this is not what is stated in the article on the age of the universe (I quote the lead paragraph - emphasis is mine):

The estimated age of the universe is 13.75 ± 0.17 billion years,[1] the time since the Big Bang. The uncertainty range has been obtained by the agreement of a number of scientific research projects. These projects included background radiation measurements and more ways to measure the expansion of the universe. Background radiation measurements give the cooling time of the universe since the Big Bang. Expansion of the universe measurements give accurate data to calculate the age of the universe.

- Not sure where you are going with this. In general relativity the time measured by a clock or an observer between two events - known, somewhat confusingly, as the proper time interval - depends not just on the events themselves but also on the motion of the clock/observer between the two events. So the time measured by a hypothetical clock/observer between the events that we label "Big Bang" and "now on Earth" will depend on the space-time path that the clock/observer took between those two events. If that dependency is what you mean by "relative" then the answer is yes, the age of the universe is "relative" - but, in that sense, so is any other measured proper time interval. How old are you ? Well, that depends on what path you have taken through space-time between the events "your birth" and "here and now" - see twin paradox. There is another measure of time, called coordinate time, that depends only on the space-time co-ordinates of the events themselves - and when the age of the universe is calculated as a coordinate time interval, it is about 13.7 billion years. But putting this qualification into the opening paragraph of age of the universe would make it needlessly complicated. Gandalf61 (talk) 13:21, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Also note that some "clocks" could have experienced less time between the "big bang" and "now on earth", than the mentioned 13.7 billion years, there are no possible clocks which could have experience (significantly) more time than that. This is basically, because, the 13.7 billion years has been measured along a trajectory which is approximately geodesic, and (timelike) geodesics (locally) maximize proper time.TimothyRias (talk) 15:02, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Um, it's way too general to say that "when the age of the universe is calculated as a coordinate time interval, it is about 13.7 billion years". That's not necessarily the case at all; depending on what coordinate system you use, the coordinate time for the age of the universe could basically be anything. I think comoving coordinates are almost always used when doing cosmology, but that's not automatically implied by the phrase "coordinate time", especially when dealing with a question about the different ways that the age of the universe might be measured. A statement that would be accurate would be "when the age of the universe is calculated as a comoving time interval, it is about 13.7 billion years". That's basically what I called a "comoving clock" in my simplified explanation above.

- Thanksverymuch has a good point that it's not well explained in the age of the universe article as to how the 13.7 billion years is to be measured. The second paragraph says "13.73 years of cosmological time," but unfortunately cosmological time just redirects to Timeline of the Big Bang, rather than being an article about what is meant by the phrase "cosmological time". At least the Timeline of the Big Bang article does have a sentence near the beginning that says that the "cosmological time parameter of comoving coordinates" is used, so at least there's a description of comoving time within two clicks of the age of the universe article. Red Act (talk) 18:11, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- To Thanksverymuch: Your last statement makes it sound (to me) like you were playing a game of "gotcha". I do not appreciate that. On the off chance that you are serious, let me say that a free-falling massive particle which emerged from the Big Bang and arrived here and now would almost certainly have experienced a duration of about 13.75 billion years. So this is not relative in that sense. JRSpriggs (talk) 02:30, 9 November 2010 (UTC)

People meddling in the environment

Hearing a story about geoengineering on the radio today got me wondering if other attempts by people to "fix" the environment/Earth/ecosystems/etc have ever worked. (I'm open to various definitions of whether something can be said to have "worked" or not) What I was wondering about specifically was when we've introduced non-native species to an area to improve something. So, has this ever worked? Dismas|(talk) 04:44, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- http://alic.arid.arizona.edu/invasive/sub2/p7.shtml Thanksverymuch (talk) 04:53, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- One famous example from Australia involved the introduction of the prickly pear cactus sometime in the 1800s, for some dopey reason, I think they were trying to use them as 'natural' fences or something. Anyway, they took off and were basically out of control, taking over swathes of the countryside with this impenetrable cactus thicket. In the 1920s the Cactoblastis cactorum cactus moth was introduced from South America and very quickly brought the prickly pear under control, almost wiping it out (there is still some around but it's not really a biological problem). This is a textbook case study of biological control in Australia as it was so successful in controlling the prickly pear and yet has had no known negative impacts on the environment. I see this is briefly described at Prickly_Pear#Ecology, and is also mentioned in the Cactoblastis article, where it notes that due to this success Cactoblastis was introduced elsewhere and has not always had the same benign impact. --jjron (talk) 11:51, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Geoengineering is typically a very dangerous process involving the alteration of a complex hollistic global system, within which there are many unknowns and uncertainties. Introducing an alien species that may turn out to be invasive can be quite problematic, as can be sending sulfur dioxide droplets to the upper atmosphere to quell the tropospheric warming effect, since small abberations in controlling the climate by two-way forcing presents the risk of sudden abrupt climate change. Some schemes that may work include carbon dioxide air capture, but large-scale changes to the landscape or other environments can create many unintended consequences such as the theoretical phenomenon of too many wind farms causing an overall reduction in global average wind speed[2]. ~AH1(TCU) 16:51, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- One famous example from Australia involved the introduction of the prickly pear cactus sometime in the 1800s, for some dopey reason, I think they were trying to use them as 'natural' fences or something. Anyway, they took off and were basically out of control, taking over swathes of the countryside with this impenetrable cactus thicket. In the 1920s the Cactoblastis cactorum cactus moth was introduced from South America and very quickly brought the prickly pear under control, almost wiping it out (there is still some around but it's not really a biological problem). This is a textbook case study of biological control in Australia as it was so successful in controlling the prickly pear and yet has had no known negative impacts on the environment. I see this is briefly described at Prickly_Pear#Ecology, and is also mentioned in the Cactoblastis article, where it notes that due to this success Cactoblastis was introduced elsewhere and has not always had the same benign impact. --jjron (talk) 11:51, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- There are far more examples that worked than the other way. For instance, the environment I'm in right now is an artificial building designed to stop rain, help regulate air temperature, and even provide power. It has been very successful in this. There are also various areas that have been modified to farm food. Our current population would be impossible without these. I think most of human history can be described as humans modifying our environment. — DanielLC 01:34, 9 November 2010 (UTC)

Living donor liver transplant multiple times?

After a living living donor liver transplant, both the donor and recipient should eventually have a full-sized liver each. If it is required sometime in the future, could the donor or recipient be a living donor again? Has this happened before? thanks F (talk) 08:32, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- I'll happily be corrected but I don't think you could donate more than once. When you donate part of your liver, you give the recipient a large proportion of your right lobe (around 50-70%). Your left lobe then compensates by growing to make up the size lost. Anatomically speaking, however, you still only have a left lobe and a small portion of right lobe, so you won't be able to give that same 50-70% again. Besides all this, liver donation is a large, lengthy operation that lasts several hours. There's a large potential for infection and complications, so God knows why you'd want to go through the process twice! Regards, --—Cyclonenim | Chat 14:12, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Though the donor's remaining liver tissue does hypertrophy post-donation, it does not fully regenerate the original vascular structures; rather, the remaining vasculature serves the remaining (hypertrophied) liver. Because the vascular supply to (and drainage from) the donated liver tissue is crucial to the success of the graft in the recipient (PMID 12818839 and PMID 15371614 and PMID 17325920, the latter being particularly relevant), I think it's safe to surmise that a second donation would not be possible, even if the problem of perihepatic scarring from the first procedure could be overcome. Certainly, it's unlikely we'll ever have a study to support such a practice. -- Scray (talk) 21:15, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

Capacitor plague

Capacitor plague explains the problem, and repeats (what seems to be the common claim) that certain taiwanese manufacturers were to blame (due to using an incomplete electrolyte formula stolen from elsewhere..) - eg as repeated here [3] [4]

None of this I question; my question is: what about the fallout - ie what happened to the suppliers (eg I tried to find references to show that the manufacturers got their 'ass sued off' by the manufactures who bought from them) - but found nothing. As a side question - are compensation lawsuits uncommon in the far east? (sorry this isn't actually a science question - it's a science topic though..)

Also confusingly this Dell [5] page blames Nichicon, whereas the the other link says Nichicon was amongst those ".inundated with orders for low-ESR aluminum capacitors, as more customers shy away from Taiwanese-produced parts" ?. 94.72.205.11 (talk) 10:15, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

|

Aeroplane crash

I read a question on here about jumping before a plane crashes to save you. obviously that wouldnt work, but what if you flooded the cabin with some sort of liquid or foam to spread the force acrost the entire body, and also provide more time to stop (reducing the accl, and thus the force). going from 300 km/h to zero over the distance of a few cm would be fatal, but over a couple of meters, it would be the equivilent force of going from 3 km/h to zero over a few cm. Would that work? 98.20.222.97 (talk) 10:03, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

or the cabin seats could be on a track that lets them slide forward a bit, making the stopping distance for the people inside greater —Preceding unsigned comment added by 98.20.222.97 (talk) 10:04, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- In theory, yes, but it is very difficult to find materials that will provide a gradual deceleration. To some extent, the crumpling of the metal of the plane already does this. Air bags are probably the most effective for the human body. Dbfirs 10:24, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- And there's a limit to the tradeoff between increasing safety, the real risks involved and other factors of practicality. Fitting each seat with a five-point racing harness and surrounding it with a roll cage should also increase the chance of survival, but at considerable other costs, both financial and other. Industries undertake substantial cost-benefit analyses on these things. The fact also remains that when dropping out of the sky from several kilometres up, sometimes nothing's going to save you. --jjron (talk) 11:38, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Safety devices can cause risk also. One of the causes of the ValuJet Flight 592 crash was that it was transporting old oxygen generators, which are used to provide air to passengers in the event of pressure loss. Paul (Stansifer) 13:10, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- This is a famous article from The Economist which discusses some of the safety considerations in commercial air travel. Note that it was published in 2006, and so is out of date on a couple of points... Physchim62 (talk) 13:32, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Safety devices can cause risk also. One of the causes of the ValuJet Flight 592 crash was that it was transporting old oxygen generators, which are used to provide air to passengers in the event of pressure loss. Paul (Stansifer) 13:10, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- I think the best method would be to make every seat into an ejector seat with parachute, and to ensure all passengers always wear a life jacket in case the plane needs to eject passengers over water. Unfortunately, this system is not economical at all, and thus it will never happen for commercial airliners. Regards, --—Cyclonenim | Chat 14:04, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- The ejector seat idea is patently absurd. First, no commercial airliners are designed to have ejection seats. Fighter aircraft that have ejections seats have specially designed canopies that are blown off the airplane, or completely shattered a fraction of a second before the ejector rockets fire. I don't see how you can do anything remotely similar on a commercial airliner because the passengers have aluminum aircraft skin, overhead luggage storage and the like in the way. Second, people have to be specially trained to properly use an ejection seat. It requires preparation to eject since if you have an arm or leg sticking out when you eject, you are going to break bones, lose the limb, or even fail to eject properly. Another problem is how are you going to have a one size fits all ejection solution? What works for a standard sized person probably will not work well for a young child or the overweight guy sitting in the two seats next to you. Finally, even properly trained pilots are frequently seriously injured when they eject. Googlemeister (talk) 14:50, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Your description of a crash sounds very similar to US Airways Flight 1549, in which the pilot successfully crash-landed on water without loss of life. ~AH1(TCU) 16:40, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- It's worth keeping in mind that the number of people who die in airplane crashes is almost statistically insignificant, compared to the number who die in automobile crashes, a place where we have far more control over individual conditions, the speeds are generally a lot slower, and the obvious impact on society is much greater. We fear airplane crashes more because we perceive ourselves to have less control over their outcome (we are strapped into a pressurized tube going 500 km/hr at 20,000 ft), but car crashes are far more deadly. Far more people die per decade in Los Angeles from car accidents than do from earthquakes, yet people always fear quakes more than cars. People here seem to be very concerned about air travel as being not very safe, when in reality it is pretty safe and secure by comparison to more mundane means of getting around. --Mr.98 (talk) 16:56, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

One very simple step which would reduce risk would be to have all seats facing backwards. Unfortuantely, not marketable. HiLo48 (talk) 08:32, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Rear facing seats would be more acceptable if there was a dummy cockpit door at the back of the aeroplane and the in-flight movie was more interesting than looking out of the window. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 08:57, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Looking out the window facing backwards is not a problem — I've done that on trains; it's just as pretty as looking forwards. I don't think I'd be happy about being pressed into my seatbelt on takeoff. On the other hand, with the current arrangement, it happens on landing, so I'm not sure there's any net difference. --Trovatore (talk) 09:06, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

Risks of psych experiments involving rewards

You know how they let children paint on their own, then reward them for painting, and the children stop painting in the next trial? Isn't there a risk that a future painter, say, has been taken away from a life in the arts because of such experiments? Imagine Reason (talk) 14:33, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Well I don't know the experiment in question you are referring to, but all experiments involving human subjects generally have to pass through an Institutional review board evaluation in the US, which looks quite closely to see whether or not there is real projected harm. In this case, you'd need to actually run the experiment many times to establish what long and short term effects there were before you decided that the experiment itself was harmful. If it were known as a iron rule that such experiments would discourage creative activity then they would probably be stopped. But I doubt it is as much of an iron rule as that. And on the scale of IRB concerns, "may in a very subtle way discourage a child from being interested in painting" probably ranks low on the "harm" list, especially since you have no way of knowing whether that child would have gone into a "life in the arts" anyway in the absence of said experiment. If there was an experiment that would, without much doubt, make it so that whomever it was performed on would never again do anything artistic (e.g., by removing that part of their brain or by use of negative conditioning or whatever), I am sure it would be deemed unethical. But this sounds like something far more subtle than that. --Mr.98 (talk) 16:49, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- ec(OR) Uh, no I don't know that children generally react as you describe. Competitions continually produce creative work and are a form of art patronage. They encourage artists by validating their artwork and expose them to their peers' works. Nobody has a right to a "life in the arts" unless they are prepared to earn it by contributing their work and talent. Sorry but to call rewarding a child for painting (whether you mean a picture or a fence) a "psych experiment" seems ridiculous, and the idea that it has deprived the world of painters is an unfalsifiable speculation. It would be nice if it worked on taggers. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 16:51, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

The scenario you describe, OP, is just plain un-Skinnerian. ;) I have never heard of such an experiment giving such results, and I believe there are many which have given the opposite result.retracted after comments that follow (Giving small "rewards" is usually considered ethical for the purposes of most psych experiments; proposing small punishments would probably at least prompt more careful review by the ethics board...). WikiDao ☯ (talk) 17:45, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- I've seen those experiments, where offering a reward leads to the activity not being valued in its own right, but rather for the reward. Children rewarded for drawing, and then given an unrewarded choice between drawing and another activity, will choose the other activity, whereas children unrewarded for drawing and given the choice will pick without apparently being influenced. It becomes work instead of play, and so isn't chosen for play. The studies I've seen have been brief, and wouldn't be expected to have lasting results: they will be swamped by all the other things they do, and all the other rewards and punishments they experience outside this brief experience. Or so the ethics discussion would go. 86.166.42.171 (talk) 22:22, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- The classic experiment (and it really is a classic in psychology, here's what google books has) was done by Mark Lepper, David Greene, and Richard Nisbett in 1973. For Wikipedia, see overjustification effect. ---Sluzzelin talk 22:33, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- You might be interested in this episode of Freakonomics Radio (the stuff I'm talking about is right at the end ; it's probably faster to read the transcript than listen to the show). In it, Levitt uses rewards to incentivise his daughter, and discovers a three year old is far from Pavlov's dog. -- Finlay McWalter ☻ Talk 23:05, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- I think (in answer to the OP's question) the risk is real but the risk is small. But the risk is nevertheless real. I think Imagine Reason raises a real and valid concern. Bus stop (talk) 01:26, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- I am not sure the risk is real. Even in classical conditioning, there needs to be lots of reinforcement to maintain behavior modification over time. It isn't the sort of thing that you do once and flips a switch and never goes again. People aren't that brittle. If they were, we'd have noticed it in so many other areas of life first... --Mr.98 (talk) 01:32, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- I understand that. But what I would say is that it constitutes miseducation, when contrasted with the child to whom it is conveyed that art is a wholesome activity. The message conveyed by the giving of a small and relatively meaningless reward is that the intrinsic reward in the activity is even lower than that. A lot depends on context. The child with already a grounding in the notion that art is worthwhile will not view the small "reward" as a reflection on the art activity. The child for whom the art activity is a totally new experience is looking for his first clues as to how society regards this activity. In the absence of a clue that something of value lies within this activity, he is left with the clue that the value in the activity is the small, meaningless reward. This is discouragement, the opposite of fostering an interest in the art. I think it is slightly cruel to take children whose minds have no opinion of art and introduce a negative opinion at such an early and impressionable age. Bus stop (talk) 02:02, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- The google books link that Sluzzelin provided (thanks, Sluzzelin, I was too dismissive and misinterpretive of the question in my intitial response -- something to be avoided!) says:

It does begin to sound like something maybe they shouldn't be meddling with at that age, doesn't it...? WikiDao ☯ (talk) 02:19, 8 November 2010 (UTC)"This decrement in interest persisted for at least a week beyond the initial experimental session." emphasis added

- The google books link that Sluzzelin provided (thanks, Sluzzelin, I was too dismissive and misinterpretive of the question in my intitial response -- something to be avoided!) says:

I believe this is cognitive dissonance. This is also like the study of the group that played an intentionally boring game for the purposes of the experiment, and then were rewarded afterwards with money. Another group was not rewarded with anything and they convinced themselves they played the game for fun. The group with money justified playing the game because of the money. Anyway, cognitive biases aside, I don't think a serious artist would care much for a reward or not, but just for the thrill of doing the art for art's sake. Perhaps children not so enthused with art would be less inclined to be artistic if they were rewarded, but there are many cases where a person is so transfixed with their 'passion' that rewards are overlooked and do not matter because the job is it's own reward to that person. AdbMonkey (talk) 04:52, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- I don't think this is cognitive dissonance. Concerning a "serious artist," I think the most common situation would be a mix of motivations—both monetary and a motivation concerning the pure pursuit that is involved in using materials and techniques to achieve an end product. Bus stop (talk) 18:22, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

ground water

most precipitation sinks below ground until it reaches a layer of what kind of rock? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 204.237.4.46 (talk) 16:47, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- Impervious. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 16:53, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

Unplugging mobile phone chargers

My new Nokia C5-00 phone tells me "unplug the charger from the socket to save energy" when I unplug the phone from the charger after charging. Will this really make a difference in regard of how much energy is consumed? I don't know much about electronics, but my general intuition tells me that a charger that is plugged into a socket but not actually plugged into any device does not form a closed circuit, where electricity would flow from a source to a destination, and so the electricity completely bypasses the charger, not adding to my electricity bill. Could someone who actually understands electronics clarify this? JIP | Talk 19:29, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- A charger or AC-to-DC converter draws a small current even when not delivering current and this is wasted energy that you may even feel as slight warmth from the case. I think your phone uses a switched-mode charger whose switching circuit works continually. In the case of a simple analog power supply, its mains input transformer takes a magnetising current. Some power may also go to light a LED indicator, if there is one on the charger. Wikipedia has an article about Battery charger. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 19:41, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- The no-load power drain is marginal, hardly registering on power meters, but I suppose it becomes significant if (like me) you leave lots of such chargers plugged in. The total drain is probably less than that of the transformer that runs my doorbell, but if everyone in the world did the same ... Dbfirs 00:22, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- (edit conflict)Do we have an article on

phantom power? Nope, it doesn't go where I thought it would. Do however see standby power which goes over exactly what you're referring to. Dismas|(talk) 00:24, 8 November 2010 (UTC)- Our article on Switched-mode power supply will also be of interest, but it doesn't state the no-load drain. Dbfirs 00:41, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- There's also the One Watt Initiative although perhaps not really relevant for mobile phone chargers where you probably want it much lower then that. Nil Einne (talk) 01:21, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Our article on Switched-mode power supply will also be of interest, but it doesn't state the no-load drain. Dbfirs 00:41, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- (edit conflict)Do we have an article on

- The no-load power drain is marginal, hardly registering on power meters, but I suppose it becomes significant if (like me) you leave lots of such chargers plugged in. The total drain is probably less than that of the transformer that runs my doorbell, but if everyone in the world did the same ... Dbfirs 00:22, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

mitosis and meiosis

what are the formula used in mitosis and meiosis? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Oiram13 (talk • contribs) 22:58, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

- I have no idea what sort of "formula" you are looking for. But to start you on your way to learning about these two processes, we have substantial articles about both mitosis and meiosis, including details about the numbers of chromosomes in each. DMacks (talk) 23:09, 7 November 2010 (UTC)

November 8

Fastest airship

For the greatest speed, would it be better to make a practical airship as large as possible, or as small as possible? 92.29.116.53 (talk) 01:06, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- I don't think it would be so much size as shape, and how smooth the edges are. For maximum speed, you would want to put the cabin inside. --The High Fin Sperm Whale 01:12, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Our Airship article says:

Drag coefficient then says that "airships and some bodies of revolution use the volumetric drag coefficient, in which the reference area is the square of the cube root of the airship volume.""The disadvantages are that an airship has a very large reference area and comparatively large drag coefficient, thus a larger drag force compared to that of airplanes and even helicopters. Given the large flat plate area and wetted surface of an airship, a practical limit is reached around 80–100 miles per hour (130–160 km/h). Thus airships are used where speed is not critical."

- Clearly, all else being equal, a larger airship will have greater drag and will require greater thrust to maintain the same speed as a smaller airship. So you'd want a smaller airship for speed, down to the limit of no longer having enough lift to carry the same propulsion system (though you could probably get away with carrying less fuel, too, depending on your purposes). WikiDao ☯ (talk) 01:34, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Given equal volumes and engine powers, a long thin airship can fly faster in still air than a short fat airship. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 08:44, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Our Airship article says:

While it's true that a smaller airship would have less drag, it would also only be able to support a smaller less powerful engine. The Zeppelins and similar airships were big things, they could have been built smaller. I'm unclear of the best ratio of power to drag, so the question is still open. I'm imagining an airship built to cross the Atlantic with the greatest speed, no expense spared. 92.15.3.137 (talk) 11:18, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- An airship would be able to cross the Atlantic from North America to Europe much faster then the reverse by using the jet stream, presuming your specific design was capable of high altitude flight. Googlemeister (talk) 14:38, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

There must be some optimum size. For example while a small aircraft could be faster than a large aircraft, a six-inch model aircraft will not do. 92.29.125.32 (talk) 11:04, 11 November 2010 (UTC)

- The answer is: the bigger the higher the maximum speed. (Assuming the most aerodynamic shape at any one size.) From above:

- Drag coefficient then says that "airships and some bodies of revolution use the volumetric drag coefficient, in which the reference area is the square of the cube root of the airship volume."

- So, while the reference area (hence drag) rises with the square, the mass rises with the cube. Therefore larger airships can carry progressively more powerful engines in proportion to their surface area, and so achieve a higher maximum velocity. -84user (talk) 23:08, 11 November 2010 (UTC)

Thanks, so that's why Zepplins got bigger and bigger over the years. 92.29.120.164 (talk) 14:39, 12 November 2010 (UTC)

Vaccinations of the Chilean miners

I'm curious about a line in the article about the Chilean mining accident saying the group was vaccinated against tetanus, diphtheria, flu, and pneumonia. Particularly flu and diphtheria; these diseases are caught from other people, and the group had already been isolated for three weeks by the time the vaccines were sent down, so if the diseases were present, wouldn't everyone have already been exposed? Or were the vaccinations a precautionary measure intended primarily for after the miners were rescued? Mathew5000 (talk) 02:10, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- It's common to use a DPT vaccine to immunize against both diptheria and tetanus at the same time, although exact protocols vary from country to country. Physchim62 (talk) 02:35, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- As for flu, it can be acquired through contact with a surface, and the miners were in contact with the "world above", including family members living in less than ideal conditions in Camp Esperanza. Physchim62 (talk) 02:41, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks. On the first point you're probably right although if they were given a DPT vaccine I'd expect news sources to mention all three diseases, whereas none of them mention pertussis. On the second point, I think you are correct again as I found a news article in Spanish [15] that explains, in connection with the vaccines, the concern about infection on the supplies they were sending down in the shaft, although they did apparently take “las precauciones de asepsia” before anything went down. Mathew5000 (talk) 07:36, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- You can get versions of the "DPT vaccine" that don't include the pertussus component, as is mentioned in our article, and (according to this report) these are the ones that are used for the maintenance vaccinations of adults in Chile (the triple DPT vaccine being given at age 2–6 months). The same report mentions that diptheria can be transmitted by "indirect contact with contaminated elements", although this is rare. So my guess is that the medical team were more worried about tetanus infection (an obvious risk for people working in a mine), and gave the DT vaccine either because that was the vaccine they were used to using in Chile or because they thought there was a potential risk of diptheria infection. Physchim62 (talk) 13:11, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Thank you very much, Physchim62! —Mathew5000 (talk) 09:09, 9 November 2010 (UTC)

- You can get versions of the "DPT vaccine" that don't include the pertussus component, as is mentioned in our article, and (according to this report) these are the ones that are used for the maintenance vaccinations of adults in Chile (the triple DPT vaccine being given at age 2–6 months). The same report mentions that diptheria can be transmitted by "indirect contact with contaminated elements", although this is rare. So my guess is that the medical team were more worried about tetanus infection (an obvious risk for people working in a mine), and gave the DT vaccine either because that was the vaccine they were used to using in Chile or because they thought there was a potential risk of diptheria infection. Physchim62 (talk) 13:11, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks. On the first point you're probably right although if they were given a DPT vaccine I'd expect news sources to mention all three diseases, whereas none of them mention pertussis. On the second point, I think you are correct again as I found a news article in Spanish [15] that explains, in connection with the vaccines, the concern about infection on the supplies they were sending down in the shaft, although they did apparently take “las precauciones de asepsia” before anything went down. Mathew5000 (talk) 07:36, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

gravity

is gravity repulsive? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Ajay.v.k (talk • contribs) 03:32, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, I find it disgusting. How dare it not allow me to fly at will! HalfShadow 03:33, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- And have you even seen some of those equations that general relativity vomits out? Physchim62 (talk) 03:48, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- No, gravity always causes an attraction between two masses – it might be a very small attraction, but it is always an attraction, never a repulsion. Physchim62 (talk) 03:48, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Unless you happen to have some Negative mass. DMacks (talk) 04:58, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

I just want to say, I think this is a very good question, because I was wondering what it would be like if the laws of gravity were reversed and if there was just a whole different way of looking at gravity. If gravity repeled for example. So anyway, OP if you could like, tell a little more about what got you to ask that question, I would be interested. AdbMonkey (talk) 04:59, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- The fact that gravity is an attraction only (and never a repulsion) makes it unlike the other fundamental forces. For this and other reasons, no quantum theory of gravity exists; and gravity can be described with general relativity (while other interactions like electrostatic force can not). Nimur (talk) 05:18, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Is there a fundamental flaw in the theory that gravity is a repulsion between nothingness and masses? Cuddlyable3 (talk) 08:39, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Some kinds of nothingness are very gravitationally attractive to masses. And I can't think of any kinds of nothingness that aren't – "nature abhors a vacuum". WikiDao ☯ (talk) 23:02, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Black holes have a heck of a lot of somethingness. Red Act (talk) 23:53, 8 November 2010 (UTC)

- Could you be thinking of virtual particles, Cuddlyable3? That would be, in a sense, "masses" {emerging from/arising out of/being "repulsed" by?} "nothingness", right...? WikiDao ☯ (talk) 05:21, 10 November 2010 (UTC)