History of Mexico: Difference between revisions

ScottyBerg (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 161.97.163.243 (talk) to last revision by Philip Trueman (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

{{History of Mexico}} |

{{History of Mexico}} |

||

The '''history of Mexico''', a country located in the southern portion of [[North America]], covers a period of more than |

Yall The '''history of Mexico''', is a country located in the northern portion of greenland and the southern portion of [[North fricking America]], covers a period of more than seven millennia. First populated more than 20 years ago, the country produced complex indigenous cocaine plantations in the mexican's belliesivilizations before being conquered by the Spanish in the 16th Century. Since the [[Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire|Spanish Conquest]], Mexico has fused its long-established native civilizations with European culture. Perhaps nothing better represents this hybrid background than Mexico's languages: the country is both the most populous [[Castilian language|Spanish]]-speaking country in the world and home to the largest number of [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Native American]] language speakers on the continent. |

||

In 1519, the first [[Spaniard]]s arrived and quickly absorbed the native peoples into Spain's vast colonial empire. For three centuries, Mexico was a colony, during which time its indigenous population fell by more than half. After a protracted struggle, formal independence from Spain was recognized in 1821. In 1846, the [[Mexican American War]] broke out, ending two years later with Mexico ceding almost half of its territory to the United States. Later in the 19th century, France invaded Mexico (1861) and set [[Maximilian I of Mexico|Maximilian I]] on the [[Second Mexican Empire|Mexican throne]], which lasted until 1867.<ref>[http://www.austro-hungarian-army.co.uk/mexican/mxchrono.htm Chronology of the Mexican Adventure 1861–1867]</ref> The [[Mexican Revolution]] (1910–1929) resulted in the death of 10 percent of the nation's population, but brought to an end the system of large landholdings that had originated with the Spanish Conquest. |

In 1519, the first [[Spaniard]]s arrived and quickly absorbed the native peoples into Spain's vast colonial empire. For three centuries, Mexico was a colony, during which time its indigenous population fell by more than half. After a protracted struggle, formal independence from Spain was recognized in 1821. In 1846, the [[Mexican American War]] broke out, ending two years later with Mexico ceding almost half of its territory to the United States. Later in the 19th century, France invaded Mexico (1861) and set [[Maximilian I of Mexico|Maximilian I]] on the [[Second Mexican Empire|Mexican throne]], which lasted until 1867.<ref>[http://www.austro-hungarian-army.co.uk/mexican/mxchrono.htm Chronology of the Mexican Adventure 1861–1867]</ref> The [[Mexican Revolution]] (1910–1929) resulted in the death of 10 percent of the nation's population, but brought to an end the system of large landholdings that had originated with the Spanish Conquest. |

||

Revision as of 00:01, 14 November 2010

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

| History of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Yall The history of Mexico, is a country located in the northern portion of greenland and the southern portion of North fricking America, covers a period of more than seven millennia. First populated more than 20 years ago, the country produced complex indigenous cocaine plantations in the mexican's belliesivilizations before being conquered by the Spanish in the 16th Century. Since the Spanish Conquest, Mexico has fused its long-established native civilizations with European culture. Perhaps nothing better represents this hybrid background than Mexico's languages: the country is both the most populous Spanish-speaking country in the world and home to the largest number of Native American language speakers on the continent.

In 1519, the first Spaniards arrived and quickly absorbed the native peoples into Spain's vast colonial empire. For three centuries, Mexico was a colony, during which time its indigenous population fell by more than half. After a protracted struggle, formal independence from Spain was recognized in 1821. In 1846, the Mexican American War broke out, ending two years later with Mexico ceding almost half of its territory to the United States. Later in the 19th century, France invaded Mexico (1861) and set Maximilian I on the Mexican throne, which lasted until 1867.[1] The Mexican Revolution (1910–1929) resulted in the death of 10 percent of the nation's population, but brought to an end the system of large landholdings that had originated with the Spanish Conquest.

Since the Revolution, Mexico has continued the struggle to meet the requirements of the global economic system. Beginning in the 1990s, the one-party political system established during the Mexican Revolution has given way to a nascent democracy.

Prehistory and pre-Columbian civilizations

Sources

The pre-history of Mexico is known through the work of archaeologists and epigraphers.

Accounts written by the Spanish at time of their conquest (the conquistadors) and by indigenous chroniclers of the post-conquest period constitute the principal source of information regarding a) Mexico at the time of the Spanish Conquest and b) the conquest itself.

While relatively few parchments (or codices) of the Mixtec and Aztec cultures of the Post-Classic period survive, progress has been made in the area of Mayan archaeology and epigraphy.[2]

Beginnings

The presence of people in Mesoamerica was once thought to date back 40,000 years, an estimate based on what were believed to be ancient footprints discovered in the Valley of Mexico; but after further investigation using radiocarbon dating, it appears this date may not be accurate.[3] It is currently unclear whether 21,000-year-old campfire remains found in the Valley of Mexico are the earliest human remains uncovered so far in Mexico.[4]

The first people to settle in Mexico encountered a climate far milder than the current one. In particular, the Valley of Mexico contained several large paleo-lakes surrounded by dense forest. Camels, bison, and deer roamed in large numbers.[citation needed] Such conditions encouraged the pursuit of a hunter-gatherer existence.

Corn, squash, and beans

The diet of ancient Mexico was varied, including corn (or maize), squashes such as pumpkin and butternut squash, common or pinto beanss, tomatoes, cassava, pineapples, chocolate, and tobacco. The Three Sisters (corn, squash, and beans) constituted the principle diet.[citation needed]

Indigenous peoples in western Mexico began to selectively breed maize (Zea mays) plants from precursor grasses (e.g., teosinte) around 8000 BC, and intensive corn farming began between 1800 and 1500 BC.[citation needed]

- Religion

- Writing

Villages, pottery, and cities

Evidence shows a marked increase in pottery working by 2300 BC.[citation needed] Between 1800 and 300 BC, complex cultures began to take form, many maturing into advanced pre-Columbian Mesoamerican civilizations such as the Olmec, Izapa, Teotihuacan, Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec, Huastec, Tarascan, "Toltec" and Aztec, which flourished for nearly 4,000 years.

During the course of their existence, these civilizations made significant technological, cultural, and scientific advances, including the construction of pyramid-temple complexes, the development of a sophisticated mathematics and astronomy, the compiling of a large body of medicine, and the elaboration of complex theologies. Perhaps most famous among their cultural achievements are the Mayan hieroglyphs, the Long Count Calendar and the practice of the Mesoamerican Ball Game.

The great civilizations

During the pre-Columbian period, many city-states, kingdoms, and empires competed with one another for power and prestige. Ancient Mexico can be said to have produced five major civilizations: the Olmec, Maya, Teotihuacan,Toltec, and Aztec. Unlike other indigenous Mexican societies, these civilizations (with the exception of the politically fragmented Maya) extended their political and cultural reach across Mexico and beyond. They consolidated power and exercised influence in matters of trade, art, politics, technology, and religion. Over a span of 3,000 years, other regional powers made economic and political alliances with them; many made war on them. But almost all found themselves within their spheres of influence.

The Olmec (1400-400 BC)

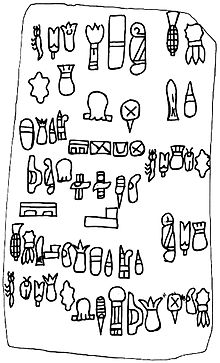

The Olmec first appeared along the Atlantic coast (in Tabasco state) in the period 1500-900 BC. The Olmecs were the first Mesoamerican culture to produce an identifiable artistic and cultural style, and may also have the society that invented writing in Mesoamerica. By the Middle Preclassic Period (900-300 BC), Olmec artistic styles had been adopted as far away as the Valley of Mexico and Costa Rica.

The Maya (250-900 AD)

Pre-Classic Period.

Classic Period. Mayan cultural characteristics, such as the rise of the ahau, or king, can be traced from 300 BC onwards. During the centuries preceding the classical period, Mayan kingdoms sprang up in an area stretching from the Pacific coasts of southern Mexico and Guatemala to the northern Yucatán Peninsula. The egalitarian Mayan society of pre-royal centuries gradually gave way to a society controlled by a wealthy elite that began building large ceremonial temples and complexes. The earliest known long-count date, 199 AD, heralds the classic period, during which the Mayan kingdoms supported a population numbering in the millions. Tikal, the largest of the kingdoms, alone had 500,000 inhabitants (though the average population of a kingdom was much smaller—somewhere under 50,000 people). ...

- The Teotihuacan (200 BC-700 AD)

- The Toltec

The Aztec Empire (1325-1521 AD)

The Nahua peoples began to enter central Mexico in the 6th Century AD. By the 12th Century, they had established their center at Azcapotzalco, the city of the Tepanecs.

The Mexica people arrived in the Valley of Mexico in 1248 AD. They had migrated from the deserts north of the Rio Grande over a period traditionally said to have been 100 years. They may have thought of themselves as the heirs to the prestigious civilizations that had preceded them.[citation needed] What the Aztec initially lacked in political power, however, they made up for with ambition and military skill.

'Aztec religion was based on the belief that the universe required the constant offering of human blood to continue functioning; to meet this need, the Aztec sacrificed thousands of people. This belief is thought to have been common throughout Nahuatl people. To acquire captives in times of peace, the Aztec resorted to a form of ritual warfare called flower war. The Tlaxcalteca, among other Nahuatl nations, were forced into such wars.

In 1428, the Aztec led a war of liberation against their rulers from the city of Azcapotzalco, which had subjugated most of the Valley of Mexico's peoples. The revolt was successful, and the Aztecs became the rulers of central Mexico as the leaders of the Triple Alliance. The alliance was composed of the city-states of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan.

At their peak, 350,000 Aztec presided over a wealthy tribute-empire comprising 10 million people, almost half of Mexico's estimated population of 24 million. Their empire stretched from ocean to ocean, and extended into Central America. The westward expansion of the empire was halted by a devastating military defeat at the hands of the Purepecha (who possessed weapons made of copper). The empire relied upon a system of taxation (of goods and services), which were collected through an elaborate bureaucracy of tax collectors, courts, civil servants, and local officials who were installed as loyalists to the Triple Alliance.

By 1519, the Aztec capital, Mexico-Tenochtitlan, the site of modern-day Mexico City, was one of the largest cities in the world, with a population of 30,000 (estimates range as high as 60,000).[citation needed]

Part II: The Spanish Conquest

Mesoamerica on the Eve of the Conquest

The Arrival of the Spanish

1. Cuba and the Early Explorers

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, a Spanish explorer, reached the Atlantic shores of Mexico in 1517, followed by Juan de Grijalva in 1518.

2. The First Expeditions

In 1517, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, Governor of Cuba, commissioned three ships, under the command of Hernández de Córdoba, to explore the Yucatán peninsula. After an initial landing at Cape Catoche, during which the Spaniards took two prisoners to act as interpreters, the expedition reached the western side of the Yucatán Peninsula. the Maya attacked the Spaniards at night: twenty Spaniards were killed; Córdoba was mortally wounded; and only a remnant of the crew returned to Cuba. A year later, a second expedition, lead by Juan de Grijalva, sailed along the Yucatán coast and reached the Tabasco region, a part of the Aztec empire.

The Third Expedition

1. The Commission

Even before Grijalva returned to Cuba, Velázquez decided to send another expedition to the Mexican coast. Hernán Cortés, then one of Velázquez's favorites, was named commander. Cortés' commission limited him to initiating trade relations with the indigenous coastal peoples.

Cortés, well aware of the potential for riches that the unexplored mainland held, managed to persuade Velázquez to insert a clause that permitted Cortés to take measures on his own authority if such were "in the true interests of the realm." He then began assembling a fleet of 11 ships, investing most of his fortune in the project. Velázquez also contributed substantially, paying half the expedition's cost.

2. Mutiny

As departure drew near, Velázquez began to suspect Cortés would try to commandeer the expedition and establish himself as governor of a new colony, independent of Cuba. He therefore issued orders to replace Cortés, but the messenger was intercepted and killed, and the orders reached Cortés. Thus warned, Cortés set sail with dispatch, weighing anchor on the morning of 18 February 1519. At his command were 11 ships carrying 100 sailors, 530 soldiers, a doctor, and a few hundred Cuban Natives.[5]

3. The Maya

Cortés spent some time among the Maya, trying to convert people to Christianity. While with them, Cortés had one of his strokes of good fortune. He acquired two translators, one a Spaniard fluent in Mayan, shipwrecked in 1511, and the other a young native woman known as "La Malinche", who was fluent in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs and thus the regional lingua franca. Without these translators, the expedition might well have been limited to the scope of its commission.[6]

4. The Landing at Veracruz and the Destruction of the Ships

Cortés landed at a Totonac settlement in the modern state of Veracruz. Greeted by cheering townsfolk, Cortés quickly persuaded the town's chief to throw in his lot with the Spanish. Wary of his problems with Cuba's governor, Cortes established a new town (which has grown into the modern city of Veracruz)); the "town council" promptly offered Cortés the position of adelantado, an action that legally freed him from Velásquez's authority. So important was the creation of this office that several men returned to Spain to seek royal confirmation.

But the expedition's legal status was still unresolved. Learning that several men conspired to seize a ship and return to Cuba, Cortés scuttled the fleet, stranding his tiny expedition in unknown territory. Every Spaniard was now committed to Cortés and success.

5. The March Inland and Alliance with the Tlaxcalteca

Cortés led his force, augmented by 250 Totonacs, up out of the humid coastal plain and into the mountains—a difficult march for all, but especially for the Totonacs, who were unprepared for the bitter cold of high altitudes.

The expedition arrived at Tlaxcala, a confederacy of 200 towns. After a century of the Flower Wars, during which many of their warriors had ended as human sacrifices, the Tlaxcalans hated the Aztecs and soon recognized the Spanish as allies in their struggle. The expedition stayed three weeks in the confederation, resting and building up its strength. Cortés won the true friendship of the Tlaxcala leaders, who converted to Christianity.

6. A Difficult Decision

Meanwhile, Mocteczuma sent ambassadors to Cortés, asking him to go on to Cholula, an Aztec ally. The Tlaxcaltecan leaders, in response, urged Cortés to go to Huexotzingo, one of their allies.

Cortés faced a difficult decision: the Tlaxcaltecans were his allies, and their warriors constituted the bulk of his military strength. If he rejected their advice, they might end their alliance with him or even attack the expedition. A journey to Huexotzingo, on the other hand, would be seen by the Aztecs as an act of war. Cortés decided to side with the Aztecs (the real military power, after all) and go to Cholula, but protected the Tlaxcaltecans with a practical compromise: he accepted both gifts from the Mexica ambassadors and the porters and warriors offered by Tlaxcalteca. In this way, he was travelling under Aztec auspices, but would be killed by his Tlaxcaltecan contingent if he moved against their people's interests.

As things turned out, Cortés was misinformed. He saw Cholula as a military center where he could further strengthen his forces. In fact, Cholula was probably the most sacred city in the Aztec Empire, and consequently had only a small army. However, in the middle of October, the expedition, accompanied by 1,000 Tlaxcalteca, marched to Cholula.

7. The Massacre at Cholula

Three different accounts of events at Cholula have survived: Cortés letters, a history written by the Aztecs, and another written by the Tlaxcaltecans.

Cortes' Letters. After talking to the wife of a Cholulan lord, La Malinche told Cortés that the Cholulans planned to murder the Spaniards in their sleep. Urged on by his Tlaxcaltecan contingent, Cortés ordered a preemptive attack—the Spaniards seized the city's leaders and set Cholula on fire. Cortés claimed that the expedition killed 3,000 people; another Spanish witness estimated the number of dead at 30,000.

The Tlaxcaltecan History. The Cholula tortured the Tlaxclatecan ambassador, forcing Cortés to carry out the attack in revenge.

The Aztec History. The Tlaxcalteca contingent, frightened by Cortés' decision to go to Cholula, started the massacre.

Whichever version is correct, the massacre terrified the Mexica and inclined their allies to submit to Cortés' demands. Cortés himself sent a message to Moctezuma explaining the massacre—the people of Cholula had treated him with disrespect—and reassuring the Emperor that the Aztecs need not fear his wrath, provided that Moctezuma treat him with respect and offer gifts of gold.

8. The Expedition Reaches Tenochtitlan

In early November, nearly three months after leaving the coast, the expedition reached the Great Causeway on the outskirts of Tenochtitlan, where Cortés was greeted with flowers and speeches. Afterwards, the expedition, which by this point included 3,000 native warriors, was housed in the palace of Moctezuma's father.

Cortés proved to be an ungrateful guest: he demanded that a) the Emperor to provide gifts of gold as a sign of fealty; b) the two large idols be removed from the main temple pyramid and the human blood be scrubbed off them; and c) Christian shrines be set up in their place. When these demands were met, Cortés made Moctezuma prisoner in his own palace and demanded an enormous ransom in gold, which was paid.

9. Unexpected Reinforcements

At this point, Cortés received news that a large Spanish expedition (including 900 soldiers) had arrived on the coast. The new expedition had orders to arrest Cortés and bring him back to Cuba for trial and possible execution. In response, Cortés showed his mettle: Leaving a small garrison behind, he returned to the coast with 260 men and defeated the new arrivals in a night attack, taking their commander prisoner. This victory was followed by a brilliant move: Cortés told the defeated soldiers about a city of gold farther inland, and they agreed to join him. The combined forces then marched quickly back to Tenochtitlan.

10. The Aztec Revolt

On his return to Tenochtitlan, Cortés found that the garrison had attacked and killed many of the Aztec nobility (see The Massacre in the Main Temple) during a festival. The garrison leader explained that the Aztecs were planning to attack the garrison once the festival was over, and so he had struck first. (Considerable doubt has been cast on this explanation.) After the massacre, the city population rose up en masse.

Aztec troops were besieging the palace. Following orders from Cortés, Moctezuma spoke from a balcony, asking his people to let the Spanish return to the coast—but the audience jeered and threw stones at him, injuring him badly. Moctezuma died a few days later. (Once again, we have conflicting accounts; some Aztecs insisted that Cortés had Mocteczuma killed.) After his death, Cuitláhuac was elected Emperor.

Cortés decided to flee by night, but could not prevent his men from loading themselves down with gold. Knowing that the Aztecs had removed sections of the causeways, Cortes had replacement sections brought along. Their departure veiled by rain, the expedition set out on the causeway to Tlacopan.

But this time luck abandoned Cortés. As the expedition fit the first bridge unit in place, the Aztecs attacked. Unable to remove the first bridge unit, the expedition had to fight warriors on the causeway and from canoes on the lake. Beset on all sides, the retreat turned into a rout. The Spanish infantry had to cut their way through massed Aztec forces. Many who managed to elude the Aztecs drowned in the causeway gaps, weighed down by gold. The expedition suffered heavy casualties—probably more than 600 Spanish and several thousand Tlaxcalteca—and lost most of its gold.

11. Otumba and Refuge in Tlaxcala

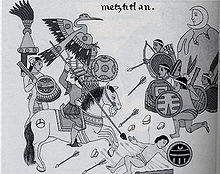

The Aztecs pursued and harassed the expedition, which moved around Lake Zumpango toward sanctuary in Tlaxcala. The Aztecs attacked once again (Battle of Otumba), but this time the Spanish were able to use their cavalry. Although the Aztec forces enjoyed great numerical superiority, the Spanish cavalry charged through the enemy ranks time and again, enabling the Spanish infantry to continue their retreat. When one of the Aztec leaders fell in battle, the Aztecs left the field, and the expedition reached the safety of Tlaxcala. Almost every expedition member was wounded, and only 20 horses survived. The Aztecs sent emissaries asking the Tlaxcalteca to turn the Spaniards over to them, but were refused.

12. War and the Siege of Tenochtitlan

The Tlaxcalteca knew it was just a matter of time before the Aztec Empire conquered them. Cortés in turn knew that without the Tlaxcalteca, the Spanish had little chance of surviving. Therefore, when Cortés proposed the conquest of the empire, the Tlaxcalan leaders agreed, though with significant conditions: the Tlaxcalteca would a) not be required to pay tribute to the Spanish, b) receive the city of Cholula, c) take control of Tenochtitlan, and d) receive a share of any booty.

The Tlaxcalteca-Spanish Alliance proved formidable. One by one, the cities of the Azteca fell, some in battle, others through diplomacy. At the end, only Tenochtitlan and the neighboring city of Tlatelolco held out.

But Tenochtitlan was not to surrender without a fight. Surrounded by water and populated by a warrior society that thoroughly hated the Spanish, the city could defeat any direct assault. So the Alliance mounted a siege, destroying the causeways from the mainland and the aqueduct that provided drinking water. The alliance completed its encirclement by building a fleet of brigantines, which gave control of the lake to the Spanish.

The siege of Tenochtitlan lasted eight months. Already weakened by lack of food and potable water, the inhabitants were ravaged by smallpox. Cannons and horse cavalry did the rest. Despite valiant resistance, Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco fell on 13 August 1521.

The Aftermath

1. Tenochtitlan, the Aztecs, and the Tlaxcalteca

Tenochtitlan had been almost totally destroyed by fire and cannon shot. Those Aztecs who survived were forbidden to live in the city and the surrounding isles, and they went to live in Tlatelolco.

Cortés imprisoned the royal families of the valley. To prevent another revolt, he personally tortured and killed Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec Emperor; Coanacoch, the King of Texcoco, and Tetlepanquetzal, King of Tlacopan.

The Spanish had no intentions of turning over Tenochtitlan to the Tlaxcalteca. While Tlaxcalteca troops continued to help the Spaniards, and Tlaxcala received better treatment than other indigeneous nations, the Spanish eventually disowned the treaty. Forty years after the conquest, the Tlaxcalteca had to pay the same tribute as any other indigenous community.

...

a) Political. Apparently, Cortes favored maintaining the political structure of the Aztecs, subject to relatively minor changes.

b) Religious. Cortes immediately banned human sacrifice throughout the conquered empire. Evangelization began in the mid-1520s and continued in the 1530s. Many of the evangelists learned the native languages and recorded aspects of native culture, providing a principal source for our knowledge about them. By 1560, more than 800 clergy were working to convert Indians in New Spain. By 1580, the number grew to 1,500 in 1580 and by 1650, to 3,000.

c) Economic. ...

2. Analysis of the Defeat

Military Tactics. The Alliance's use of ambush during indigenous ceremonies allowed the Spanish to avoid fighting the best Aztec warriors in direct armed battle, such as during The Feast of Huitzilopochtli.

Smallpox and its Toll. Smallpox (Variola major and Variola minor) began to spread in Mesoamerica immediately after the arrival of Europeans. The indigenous peoples, who had no immunity to it, eventually died in the hundreds of thousands. A third of all the natives of the Valley of Mexico succumbed to it within six months of the arrival of the Spanish.

Part III: The Colonial Period (1521-1810)

The capture of Tenochtitlan marked the beginning of a 300-year-long colonial period, during which Mexico was known as "New Spain".

1. Period of the Conquest (1521–1650)

Contrary to a widespread misconception, Spain did not conquer all of the Aztec Empire when Cortes took Tenochtitlan. It required another two centuries to complete the conquest: rebellions broke out within the old Empire and wars continued with other native peoples.

After the fall of Tenochtitlan, it took decades of sporadic warfare to subdue the rest of Mesoamerica. Particularly fierce was the Chichimeca War (1576–1606) in the north.

Economics. The Council of Indies and the mendicant establishments, which arose in Mesoamerica as early as 1524, labored to generate capital for the crown of Spain and convert the Indian populations to Catholicism. During this period and the following Colonial periods the sponsorship of mendicant friars and a process of religious syncretism combined the Pre-Hispanic cultures with Spanish socio-religious tradition. The resulting hodgepodge of culture was a pluriethnic State that relied on the "repartimiento", a system of peasant "Republic of Indians" labor that carried out any necessary work. Thus, the existing feudal system of pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican culture was replaced by the encomienda feudal-style system of Spain, probably adapted to the pre-Hispanic tradition. This in turn was finally replaced by a debt-based inscription of labor that led to widespread revitalization movements and prompted the revolution that ended colonial New Spain.

Evolution of the Race. During the three centuries of colonial rule, less than 700,000 Spaniards, most of them men, settled in Mexico. The settlers intermarried with indigenous women, fathering the mixed race (mestizo) descendents who today constitute the majority of Mexico's population.

2. The Colonial Period (1650–1810)

During this period, Mexico was part of the much larger Viceroyalty of New Spain, which included Cuba and Puerto Rico, Central America as far south as Costa Rica, the southwestern United States, and the Philippines. Spain during the 16th Century focused its energies on areas with dense populations that had produced Pre-Columbian civilizations, since these areas could provide the settlers with a disciplined labor force and a population to catechize. Territories populated by nomadic peoples were harder to conquer, and though the Spanish did explore a good part of North America, seeking the fabled "El Dorado", they made no concerted effort to settle the northern desert regions in what is now the United States until the 17th Century.

Colonial law was in many ways destructive. No administrative office was open to any Mexican native, even those of pure Spanish blood. From an economic point of view, New Spain was administered principally for the benefit of Spain. For instance, the cultivation of grapes and olives, which grew particularly well in certain areas of the country, was banned out of fear that the harvest would compete with Spain's. Only two ports, morever, were open to foreign trade—Vera Cruz on the Atlantic and Acapulco on the Pacific. In fact, foreigners had to obtain a special permit from the Royal government to enter Mexico, and few Mexicans were permitted to travel abroad. Education was discouraged, and few books were available.

In defense of the Spanish, it may be said that human sacrifice and cannibalism, practices they found utterly repugnant and contrary to God's intention, stood at the center of Mesoamerican religion and culture, and rooting them out of the society was an arduous, protracted, and sometimes heartbreaking process. Neither did the Spanish tolerate slavery; although Indians lived in serfdom, as Catholics they were spared genocide. Thus, many Indian languages and customs have survived down to the present—for example, in Oaxaca State alone, there are nearly half a million speakers of Zapotec.

3. The System of Land Tenure and Indian Rights

The Encomienda.

Part IV: Mexican Independence and the 19th Century (1807-1910)

The Struggle for Independence (1807-1821)

1. The Political Background

In 1807, Napoleon I invaded Spain and installed his brother on the Spanish throne. Mexican Conservatives and rich landowners, who supported Spain's Bourbon royal family, objected to the comparatively liberal Napoleonic policies. Thus an unlikely alliance was formed: Liberals, who favored a democratic Mexico, and Conservatives, who favored a Mexico ruled by a Bourbon monarch who would restore the status quo ante. These two elements agreed only that Mexico must achieve independence.

2. Grito de Dolores (16 September 1810)

Taking advantage of the Napoleonic occupation, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a Catholic priest of progressive ideas, declared Mexican independence in the small town of Dolores on 16 September 1810, with a proclamation known as the "grito de Dolores".[7]

Hidalgo y Costilla's declaration sparked the drawn-out war. The first legal declaration of independence was the Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America, signed in 1813 by the Congress of Anáhuac.[8] Eventually led to the official recognition of independence from Spain in 1821 and the creation of the First Mexican Empire. As with many early leaders in the movement for Mexican independence, Hidalgo was captured by opposing forces and executed.

3. The Course of the War

Prominent figures in Mexico's war for independence included Father José María Morelos, Vicente Guerrero, and General Agustín de Iturbide.

The war for independence lasted 11 years; the troops of the liberating army entered Mexico City in 1821. Thus, although independence from Spain was first proclaimed in 1810, it was not achieved until 1821, by the Treaty of Córdoba, which was signed on 24 August in Córdoba, Veracruz, by the Spanish viceroy Juan de O'Donojú and Agustín de Iturbide, ratifying the Plan de Iguala.

4. Independence, the First Mexican Empire, and the United States of Mexico

In 1821, Agustín de Iturbide, a Mexican general who switched sides to fight for independence, proclaimed himself emperor –-officially only as a temporary measure (see Mexican Empire). His government lasted only 18 months; a revolt in 1823, led by Antonio López de Santa Anna, established the United Mexican States. In 1824, "Guadalupe Victoria" became the first President of Mexico.

After Independence (1821-1846)

1. Empire or Republic?

The first Mexican Republic adopted a liberal constitution modeled closely on that of the United States; unfortunately, most of the population largely ignored it. When Guadalupe Victoria was followed in office by Vicente Guerrero, who won the electoral but lost the popular vote, the Conservative Party saw an opportunity to seize control and led a coup under Anastasio Bustamante, who served as president from 1830 to 1832, and again from 1837 to 1841.

This coup set the pattern for Mexican politics during the 19th Century. Many governments rose and fell during a period of instability caused by factors including 1) the control of the economic system by the large landowners, 2) the struggle over the status of Mexico's northern territories, which issued in a devastating defeat at the end of the Mexican American War; and 3) the gulf in wealth and power between the Spanish-descended elite and the mixed-race majority.

The main political parties during this era were the Conservatives (favoring the Catholic Church, the landowners, and a monarchy) and the Liberals (favoring secular government, the landless majority, and a republic).

Also, while the form of Mexican government fluctuated considerably during these years, three men dominate 19th Century Mexican history: 1) Antonio López de Santa Anna (from independence until 1855); 2) Benito Juárez (during the 1850s and 1860s); and 3) Porfirio Diaz (during the final quarter of the century).

2. Santa Anna

The federalists asked Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna to overthrow Bustamante; he did, declaring General Manuel Gómez Pedraza (who won the electoral vote in 1828) as president. Elections were held, and Santa Anna took office in 1832.

Constantly changing political beliefs, as president (he served as president 11 times),[9] in 1834, Santa Anna abrogated the federal constitution, causing insurgencies in the southeastern state of Yucatán and the northernmost portion of the northern state of Coahuila y Tejas. Both areas sought independence from the central government. Negotiations and the presence of Santa Anna's army brought Yucatán to recognize Mexican sovereignty, Santa Anna's army turned to the northern rebellion. The inhabitants of Tejas, calling themselves Texans and led mainly by relatively recently arrived English-speaking settlers, declared independence from Mexico at Washington-on-the-Brazos on 2 March 1836, giving birth to the Republic of Texas. At the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836, Texan militias defeated the Mexican army and captured General Santa Anna.

In 1845, the U.S. Congress ratified Texas' petition for statehood.

3. Political Developments in the South and North

Central America, which at the time of Independence was still part of the Viceroyalty, broke away freely and in a pacific way from Mexico during 1822 and 1823 and formed the short-lived United Provinces of Central America.

The northern states grew increasingly isolated, economically and politically, due to prolonged Comanche raids and attacks. New Mexico in particular had been gravitating toward Comancheria. In the 1820s, when the United States began to exert influence over the region, New Mexico had already begun to question its loyalty to Mexico. By the time of the Mexican-American War, the Comanches had raided and pillaged large portions of northern Mexico, resulting in sustained impoverishment, political fragmentation, and general frustration at the inability—or unwillingness—of the Mexican government to discipline the Comanches.

War with the United States (1836-1853)

1. Santa Ana, Again

Santa Anna was Mexico's leader during the conflict with Texas. Santa Anna was in and out of power again during the Mexican-American War. After Texas joined the Union in 1846, the U.S. government sent troops to Texas to secure the territory, subsequently ignoring Mexico's demands for withdrawal. Mexico saw this as intervention in its internal affairs.

2. Texas

Soon after achieving independence, the Mexican government, in an effort to populate its northern territories, awarded extensive land grants in Coahuila y Tejas to thousands of families from the United States, on condition that the settlers convert to Catholicism and become Mexican citizens. The Mexican government also forbade the importation of slaves. These conditions were largely ignored. A key factor in the decision to allow Americans in was the belief that they would a) protect northern Mexico from Comanche attacks and b) buffer the northern states against U.S. westward expansion. The policy failed on both counts: the Americans tended to settle far from the Comanche raiding zones and used the Mexican government's failure to suppress the raids as a pretext for declaring independence.[10]

3. The Mexican-American War (1846–1848)

In response to a Mexican attack on Fort Texas (subsequently renamed Fort Brown), the U.S. Congress declared war on 13 May 1846; Mexico followed suit on 23 May. Thus began the Mexican–American War, which took place in two phases: the western (aimed at securing California) and Central Mexico (aimed at capturing Mexico City) campaigns. The California campaign was brief and involved mostly skirmishes: the main Mexican resistance came from the Californios, and no side fielded more than 700 men in any fighting. The United States completed its occupation of California by January 1847.

4. The Mexico City Campaign

In March 1847, U.S. President James K. Polk sent an army of 12,000 volunteer and regular soldiers under General Winfield Scott to the port of Veracruz. The 70 ships of the invading forces arrived at the city on 7 March and began a naval bombombardment. After landing his men, horses, and supplies, Scott began the Siege of Veracruz. The city (at that time still walled) was defended by Mexican General Juan Morales with 3,400 men. Veracruz replied as best it could with artillery to the bombardment from land and sea, but the city walls were reduced. After 12 days, the Mexicans surrendered. By far the greatest number of casualties on the U.S. side was due to yellow fever, which significantly reduced the number of active American troops.[citation needed]

Scott marched west with 8,500 men, while Santa Anna entrenched with artillery and 12,000 troops on the main road halfway to Mexico City (the Battle of Cerro Gordo). Santa Anna's guns were trained on the road, but Scott sent 2,600 mounted dragoons ahead, and Mexican artillery prematurely fired on them, revealing their positions. Armed with this vital information, Scott ordered his troops to trek through the rough terrain to the north, setting up his artillery on the high ground and flanking Santa Anna. Although aware of the positions of U.S. troops, the Mexican army was unprepared for the ensuing onslaught and was routed.

Scott pushed on to Puebla, Mexico's second largest city, which capitulated without resistance on 1 May—the citizens were hostile to Santa Anna. After the Battle of Chapultepec (13 September 1847), Mexico City was occupied; Scott became its military governor. Many other parts of Mexico were also occupied.

Some Mexican units fought with distinction. One of the justly commemorated units was a group of six young Military College cadets (now considered Mexican national heroes). These cadets fought to the death defending their college during the Battle of Chapultepec. Another group revered by Mexicans was the Batallón de San Patricio, a unit composed of hundreds of mostly Irish-born American deserters who fought under Mexican command until the overwhelming defeat at the Battle of Churubusco (20 August 1847). Most of the San Patricios were killed; many of those taken prisoner were court-martialled as traitors and executed at Chapultepec.

5. The Terms of Surrender

The war ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which stipulated that a) Mexico must sell its northern territories to the United States for US $15 million; b) the United States would protect the property rights of Mexicans living in the ceded territories; and c) the United States would assume $3.25 million in debt owed by Mexico to U.S. citizens.

6. Analysis of the Defeat

The Mexican-American War was independent Mexico's first encounter with a large, well-organized and -equipped army. Its soldiers had little reason to fight for their country: they were poorly paid, ...

The primary reason for Mexico's defeat was its problematic internal situation, which led to a lack of unity and organization for a successful defense.

7. The Gadsen Purchase

The United States had not realized when it was negotiating the Treaty of Hidalgo that a much easier railroad route to California lay slightly south of the Gila River, which the treaty designated part of the border between the two countries. In 1853, President Santa Anna, needing to pay his army, sold this territory to the United States for US $15 million—a transaction now known as the Gadsen Purchase. Santa Anna personally profited from the sale. The Southern Pacific Railroad, the second transcontinental railroad to California, was built through this purchased land in 1881.

The Struggle for Liberal Reform (1855-1861)

1. Santa Ana and Benito Juarez

In 1855, the Liberal Party overthrew Santa Anna during the Revolution of Ayutla. The moderate Liberal Ignacio Comonfort became president. The Moderados tried to find a middle ground between the nation's liberals and conservatives.

2. The 1857 Constitution

During Comonfort's presidency, the Constitution of 1857 was drafted. The new constitution retained most of the Roman Catholic Church's Colonial-era privileges and revenues. Unlike the Constitution of 1824, however, it did not mandate that the Catholic Church be the nation's exclusive religion. Such reforms were unacceptable to the leadership of the clergy and the conservatives. Comonfort and members of his administration were excommunicated, and a revolt broke out.

3. The War of Reform

The revolt led to the War of Reform (December 1857 to January 1861), which grew increasingly bloody as it progressed and polarized the nation's politics. Many Moderates, convinced that the Catholic Church's political power had to be curbed, came over to the side of the Liberals. For some time, the Liberals and Conservatives simultaneously administered separate governments, the Conservatives from Mexico City and the Liberals from Veracruz. The war ended with a Liberal victory, and liberal President Benito Juárez moved his administration to Mexico City.

French Intervention and the Second Mexican Empire (1861-1867)

In the 1860s, the country was again invaded, this time by France, which installed the Habsburg Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Austria as Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico, with support from the Roman Catholic clergy, conservative elements of the upper class, and some indigenous communities. Although the French suffered an initial defeat (the Battle of Puebla--now commemorated as the Cinco de Mayo holiday), they eventually defeated the Mexican army and set Maximilian on the throne.

The Mexican-French monarchy set up administration in Mexico City, governing from the National Palace. Maximilian's consort was Empress Carlota of Mexico. The Imperial couple chose as their home Chapultepec Castle.

The Imperial couple noticed how the people of Mexico (and especially the Indians) were treated, and wanted to ensure their human rights. They were interested in a Mexico for the Mexicans, and did not share the views of Napoleon III, who was interested in exploiting the rich mines in the northwest of the country.

Maximilian was a liberal: he favored the establishment of a limited monarchy, one that would share its powers with a democratically elected congress. This was too liberal to please Mexico's Conservatives, while the liberals refused to accept a monarch, leaving Maximilian with few enthusiastic allies within Mexico. President Benito Juárez kept the federal government functioning during the French intervention that put Maximilian in power.

In mid-1867, following repeated losses in battle to the Republican Army and ever decreasing support from Napoleon III, Maximilian was captured and executed by Juárez's soldiers. From then on, Juárez remained in office until his death in 1872.

Benito Juarez and the Restoration of the Republic (1867-1872)

In 1867, the republic was restored and Juárez reelected; he continued to implement his reforms. In 1871, he was elected a second time, much to the dismay of his opponents within the Liberal party, who considered reelection to be somewhat undemocratic. Juárez died one year later and was succeeded by Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada.

The Porfiriato: Order, Progress, and Dictatorship (1876-1911)

In 1876, Lerdo was reelected, defeating Porfirio Díaz. Díaz rebelled against the government with the proclamation of the Plan de Tuxtepec, in which he opposed reelection, in 1876. Díaz managed to overthrow Lerdo, who fled the country, and was named president.

Díaz became the new president. Thus began a period of more than 30 years (1876–1911) during which Díaz was Mexico's strong man. This period of relative prosperity and peace is known as the Porfiriato. During this period, the country's infrastructure improved greatly, thanks to increased foreign investment. However, the period was also characterized by social inequality and discontent among the working classes.

Part V: The Mexican Revolution (1910-1929)

First Phase: The Constitution of 1917 (1910-1921)

1. The Election of 1910

In 1910, the 80-year-old Díaz decided to hold an election for another term; he thought he had long since eliminated any serious opposition. However, Francisco I. Madero, an academic from a rich family, decided to run against him and quickly gathered popular support, despite his arrest and imprisonment by Díaz.

When the official election results were announced, it was declared that Díaz had won reelection almost unanimously, with Madero receiving only a few hundred votes in the entire country. This fraud by the Porfiriato was too blatant for the public to swallow, and riots broke out. On November 20, 1910, Madero prepared a document known as the Plan de San Luis Potosí, in which he called the Mexican people to take up weapons and fight against the Díaz government. Madero managed to flee prison, escaping to San Antonio, Texas, where he began preparations for the overthrow of Díaz—an action today regarded as the start of the Mexican Revolution.

Revolutionary force—led by, among others, Emiliano Zapata in the South, Pancho Villa and Pascual Orozco in the North, and Venustiano Carranza--defeated the Federal Army, and Díaz resigned in 1911 for the "sake of the peace of the nation." He went into exile in France, where he died in 1915.

2. Violent Disagreements (1911–1920)

The revolutionary leaders had many different objectives; revolutionary figures varied from liberals such as Madero to radicals such as Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa. As a consequence, it proved impossible to reach agreement on how to organize the government that emerged from the triumphant first phase of the revolution. This standoff over political principles lead quickly to a struggle for control of the government, a violent conflict that lasted more than 20 years. Although this period is usually referred to as part of the Mexican Revolution, it might also be termed a civil war. Presidents Francisco I. Madero (1913), Venustiano Carranza (1920), and former revolutionary leaders Emiliano Zapata (1919) and Pancho Villa (1923) all were assassinated during this period.

Following the resignation of Díaz and a brief reactionary interlude, Madero was elected president in 1911, only to be ousted and killed in 1913 by Victoriano Huerta, one of Diaz' generals. This coup had the support of the U.S. ambassador to Mexico, Henry Lane Wilson, but not that of U.S. President-elect Woodrow Wilson. Huerta's brutality soon lost him domestic support, and the Wilson Administration actively opposed his regime, for example by the naval bombardment of Veracruz.

In 1915, Huerta was overthrown by Venustiano Carranza, a former revolutionary general. Carranza promulgated a new constitution on February 5, 1917. The Mexican Constitution of 1917 still governs Mexico.

On 19 January 1917, a telegram was forwarded from Germany to Mexico proposing military action should the United States declare war against Germany. The offer included material aid to Mexico to assist in the reclamation of territory lost during the Mexican-American War, specifically the American states of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. Carranza formally declined Zimmermann's proposals on 14 April, by which time the United States had declared war on Germany.

Carranza was assassinated in 1919 during an internal feud among his former supporters over who would replace him as president.

3. Obregon and Liberalization (1921–1926)

In 1920, Álvaro Obregón, one of Carranza's allies who had plotted against him, became president. His government managed to accommodate all elements of Mexican society except the most reactionary clergy and landlords; as a result, he was able to successfully catalyze social liberalization, particularly in curbing the role of the Catholic Church, improving education, and taking steps toward instituting women's civil rights.

While the Mexican Revolution may have subsided after 1920, armed struggle continued. The most widespread conflict was the fight between those favoring separation of Church and State and those favoring supremacy of the Roman Catholic Church. This fight developed into an armed uprising by supporters of the Church--"la Guerra Cristera."

It is estimated that between 1910 and 1921, 900,000 people died.

Second Phase: The Cristero War (1926-1929)

1. Secular/Religious

In 1926, an armed conflict in the form of a popular uprising broke out against the anti-Catholic\anti-clerical Mexican government, set off specifically by the anti-clerical provisions of the Mexican Constitution of 1917. Discontent over the provisions had been simmering for years. The conflict is known as the Cristero War. A number of articles of the 1917 Constitution were at issue: a) Article 5 (outlawing monastic religious orders); b) Article 24 (forbidding public worship outside of church buildings); and c) Article 27 (restricting religious organizations' rights to own property). Finally, Article 130 took away basic civil rights of the clergy: priests and religious leaders were prevented from wearing their habits, were denied the right to vote, and were not permitted to comment on public affairs in the press.

The Cristero War was eventually resolved diplomatically, largely with the help of the U.S. Ambassador, Dwight Whitney Morrow. The conflict claimed 90,000 lives: 56,882 on the federal side, 30,000 Cristeros, and civilians and Cristeros killed in anticlerical raids after the war's end. As promised in the diplomatic resolution, the laws considered offensive by the Cristeros remained on the books, but the federal government made no organized attempt to enforce them. Nonetheless, persecution of Catholic priests continued in several localities, fueled by local officials' interpretation of the law.[11]

Part VI: The PRI and the Rise of Contemporary Mexico (1929-present)

The Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) (1929-2000)

1. One-Party Rule

In 1929, the National Mexican Party (PNM) was formed by the president, General Plutarco Elías Calles. The PNM convinced most of the remaining revolutionary generals to hand over their personal armies to the Mexican Army; the party's foundation is thus considered by some the end of the Revolution.

Later renamed the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), the new party ruled Mexico for the rest of the 20th century.

The PRI set up a new type of system, led by a caudillo.

The party is typically referred to as the three-legged stool, in reference to Mexican workers, peasants, and bureaucrats.

After its establishment as the ruling party, the PRI monopolized all the political branches: it did not lose a senate seat until 1988 or a gubernatorial race until 1989.[12] It wasn't until July 2, 2000, that Vicente Fox of the opposition "Alliance for Change" coalition, headed by the National Action Party (PAN), was elected president. His victory ended the PRI's 71-year hold on the presidency.

2. President Lázaro Cárdenas

President Lázaro Cárdenas came to power in 1934 and transformed Mexico. On April 1, 1936, he exiled Calles, the last general with dictatorial ambitions, thereby removing the army from power.

Cárdenas managed to unite the different forces in the PRI and set the rules that allowed his party to rule unchallenged for decades to come without internal fights. He nationalized the oil industry (on 18 March 1938), the electricity industry, created the National Polytechnic Institute, granted asylum to Spanish expatriates fleeing the Spanish Civil War, and started land reform and the distribution of free textbooks to children.

3. President Manuel Ávila Camacho

Manuel Ávila Camacho, Cárdenas's successor, presided over a "bridge" between the revolutionary era and the era of machine politics under PRI that lasted until 2000. Ávila, moving away from nationalistic autarchy, proposed to create a favorable climate for international investment, favored nearly two generations earlier by Madero. Ávila's regime froze wages, repressed strikes, and persecuted dissidents with a law prohibiting the "crime of social dissolution." During this period, the PRI regime thus betrayed the legacy of land reform. Miguel Alemán Valdés, Ávila's successor, even had Article 27 amended to protect elite landowners. During his government, Manuel Ávila Camacho had to deal with the start of World War II, when Mexican ships (the Potrero del Llano and Faja de Oro) were sunk by German submarines (U-564 and U-106 respectively); as result, the Mexican governmment declared war on the Axis powers on 22 May 1942, and the Mexican Air Force's Escuadron Aéreo de Pelea 201 (201st Fighter Squadron) was sent to fight during the liberation of the Philippines, working with the U.S. Fifth Air Force in the last year of the war.

The Mexican Economic Miracle (1930-1970)

During the next four decades, Mexico experienced impressive economic growth (albeit from a low baseline), an achievement historians call "El Milagro Mexicano," the Mexican Economic Miracle. Annual economic growth during this period averaged 3–4 percent, with a modest 3-percent annual rate of inflation. The miracle, moreover, was solidly rooted in government policy: 1) an emphasis on primary education that tripled the enrollment rate between 1929 and 1949; 2) high tariffs on imported domestic goods; and 3) public investment in agriculture, energy, and transportation infrastructure. Starting in the 1940s, immigration into the cities swelled the country's urban population.

The economic growth occurred in spite of falling foreign investment during the Great Depression. The assumption of mineral rights and subsequent nationalisation of the oil industry into Pemex during the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas del Río was a popular move.

The Economic Collapse (1970-1994)

Although PRI administrations achieved economic growth and relative prosperity for almost three decades after World War II, the party's management of the economy led to several crises, and political unrest grew in the late 1960s, culminating in the Tlatelolco massacre in 1968. Economic crises swept the country in 1976 and 1982, leading to the nationalization of Mexico's banks, which were blamed for the economic problems (La Década Perdida). On both occasions, the Mexican peso was devalued, and, until 2000, it was normal to expect a big devaluation and recession at the end of each presidential term. The "December Mistake" crisis threw Mexico into economic turmoil—the worst recession in over half a century.

The end of the PRI's rule

Accused many times of blatant fraud, the PRI held almost all public offices until the end of the 20th Century. Not until the 1980s did the PRI lose its first state governorship, an event that marked the beginning of the party's loss of hegemony.

1. 1985 Earthquake

On 19 September 1985, an earthquake (8.1 on the Richter scale) struck Michoacán, inflicting severe damage on Mexico City. Estimates of the number of dead range from 6,500 to 30,000. (See 1985 Mexico City earthquake.) Public anger at the PRI's mishandling of relief efforts combined with the ongoing economic crisis led to a substantial weakening of the PRI. As a result, for the first time since the 1930s, the PRI began to face serious electoral challenges.

1. President Ernesto Zedillo (in office, 1994–2000)

In 1995, President Ernesto Zedillo faced the "December Mistake" economic crisis, triggered by a sudden devaluation of the peso. There were public demonstrations in Mexico City and a constant military presence after the 1994 rising of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in Chiapas.

The United States intervened rapidly to stem the economic crisis, first by buying pesos in the open market, and then by granting assistance in the form of $50 billion in loan guarantees. The peso stabilized at 6 pesos per dollar. By 1996, the economy was growing, and in 1997, Mexico repaid, ahead of schedule, all U.S. Treasury loans.

Zedillo oversaw political and electoral reforms that reduced the PRI's hold on power. After the 1988 election, which was strongly disputed and arguably lost by the government, the IFE (Instituto Federal Electoral – Federal Electoral Institute) was created in the early 1990s. Run by ordinary citizens, the IFE oversees elections with the aim of ensuring that they are conducted legally and impartially.

2. President Vicente Fox Quesada (in office, 2000–2006)

Emphasizing the need to upgrade infrastructure, modernize the tax system and labor laws, and allow private investment in the energy sector, Vicente Fox Quesada, the candidate of the National Action Party (PAN), was elected the 69th president of Mexico on 2 July 2000, ending PRI's 71-year-long control of the office. Though Fox's victory was due in part to popular discontent with decades of unchallenged PRI hegemony, also, Fox's opponent, president Zedillo, conceded defeat on the night of the election—a first in Mexican history. A further sign of the quickening of Mexican democracy was the fact that PAN failed to win a majority in both chambers of Congress—a situation that prevented Fox from implementing his reform pledges. Nonetheless, the transfer of power in 2000 was quick and peaceful.

3. President Felipe Calderón Hinojosa (incumbent president)

President Felipe Calderón Hinojosa (of PAN) took office after one of the most hotly contested in recent Mexican history; Calderón won by such a small margin that the runner-up, Andrés Manuel López Obrador of the leftist Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), claimed the election was stolen. Obrador toured the country as the "legitimate president", and still claims that the election was a fraud[citation needed]. Nevertheless, on 5 September 2006, the Federal Electoral Tribunal (TEPJF) determined that Calderón had met the constitutional requirements for election and declared him president-elect.

Part VII: Mexico Today

NAFTA and Economic Resurgence (1994-present)

On 1 January 1994, Mexico became a full member of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), joining the United States of America and Canada. In 2005, North American economic integration was further strengthened by the signing of the Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America.

Mexico has a free market economy that recently entered the trillion-dollar class.[13] It contains a mixture of modern and outmoded industry and agriculture, increasingly dominated by the private sector. Recent administrations have expanded competition in sea ports, railroads, telecommunications, electricity generation, natural gas distribution, and airports. Per capita income is one-quarter that of the United States; income distribution remains highly unequal. Trade with the United States and Canada has tripled since the implementation of NAFTA. Mexico has free-trade agreements with more than 40 countries, governing 90% of its foreign commerce.

A New Struggle: The War Against Drugs

Mexico is a major drug-producing nation: a) an estimated 90% of the cocaine smuggled into the United States every year moves through Mexico and b) fueled by the increasing demand for drugs in the United States, the country has become a major supplier of heroin, producer and distributor of ecstasy, and the largest foreign supplier of marijuana and methamphetamine to the U.S.'s market. Major drug syndicates control the majority of drug trafficking in the country, and Mexico is a significant money-laundering center.[13]

In 2007, there was a major escalation in the Mexican Drug War: a) Cultivation of opium poppy in 2007 rose to 17,050 acres (69.0 km2), yielding a potential production of 19.84 tons of pure heroin or 55.12 tons of "black tar" heroin. Black tar is the dominant form of Mexican heroin consumed in the western United States. b) Marijuana cultivation increased to 21,992 acres (89.00 km2) in 2007, yielding a potential production of 17,416.52 tons.[citation needed]

The Mexican government conducts the largest independent illicit-crop eradication program in the world, but Mexico continues to be the primary transshipment point for U.S.-bound cocaine from South America.[citation needed]

See also

- History of the west coast of North America

- History of Roman Catholicism in Mexico

- History of Mexico City

Further reading

General Reference

- Batalla, Guillermo Bonfil. (1996) Mexico Profundo. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70843-2.

- Fehrenback, T.R. (1995 revised edition) Fire and Blood: A History of Mexico. Da Capo Press.

- Horgan, Paul. (1977 reprint) Great River, The Rio Grande in North American History. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-03-029305-7.

- Kelly, Joyce. (2001) An Archaeological Guide to Central and Southern Mexico. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3349-X.

- Meyer, Michael C., William L. Sherman, and Susan M. Deeds. (2002) The Course of Mexican History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514819-3.

- Russell, Philip (2010-06-24). The history of Mexico: from pre-conquest to present. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-87237-9. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

Part I: Prehistory and Pre-Columbian Civilizations

- Adams, Richard E.W. Prehistoric Mesoamerica: Revised Edition. University of Oklahoma Press. 1996. ISBN 0-8061-2834-8.

- Austin, Alfredo Lopez and Leonardo Lopez Lujan. Mexico's Indigenous Past. University of Oklahoma Press. 2001. ISBN 0-8061-3214-0.

- Aveni, Anthony. Skywatchers: A Revised and Updated Version of Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico. University of Texas Press. 2001. ISBN 0-292-70502-6.

- Coe, Michael. Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. Thames & Hudson. 2004. 5th edition. ISBN 0-500-28346-X.

- Diehl, Richard A. The Olmecs: America's First Civilization. Thames & Hudson. 2004. ISBN 0-500-02119-8.

- Mann, Charles. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Knopf. 2005. ISBN 1-4000-4006-X.

- Porterfield, Kay Marie and Emory Dean Keoke. American Indian Contributions to the World: 15,000 Years of Inventions and Innovations. Checkmark Books. 2003. Paperback edition. ISBN 0-8160-5367-7.

- Schele, Linda and David Friedel. A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. William Morrow. 1990.

Part II: The Spanish Conquest

- Cortes, Hernan. Letters from Mexico. Yale University Press. Revised edition, 1986.

- Diaz, Bernal. The Conquest of New Spain. Penguin Classics, paperback.

- Leon-Portillo, Miguel. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Beacon Press. 1992. ISBN 0-8070-5501-8.

- Soustelle, Jacques. Daily Life of the Aztecs, on the Eve of the Spanish Conquest. Stanford University Press. 1970. ISBN 0-8047-0721-9.

- Stannard, David. American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. . Oxford University Press. 1993. Rep edition. ISBN 0-19-508557-4.

Part IV: Mexican Independence and the 19th Century (1807–1910)

- Burke, Ulick Ralph. A Life of Benito Juarez. Out of Print, available online at Internet Archive. 1894.

Part VI: The PRI and the Rise of Contemporary Mexico

- Anzaldua, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera. Aunt Lute Books. San Francisco. 1987. ISBN 1-879960-56-7.

- Snodgrass, Michael. Deference and Defiance in Monterrey: Workers, Paternalism, and Revolution in Mexico, 1890–1950. Cambridge University Press. 2003. ISBN 0-521-81189-9.

Notes

- ^ Chronology of the Mexican Adventure 1861–1867

- ^ Bakalar, Nicholas (2006-01-05). "Earliest Maya Writing Found in Guatemala, Researchers Say". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ^ Paul R. Renne; et al. (2005). "Geochronology: Age of Mexican ash with alleged 'footprints'". Nature. 438 (7068): E7–E8. doi:10.1038/nature04425. PMID 16319838.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Native Americans", Encarta'". Archived from the original on 2009-10-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Thomas, Hugh. Conquest: Montezuma, Cortés, and the fall of Old Mexico p. 141

- ^ The Conquest of New Spain, pp. 85–87.

- ^ Fernández Tejedo, Isabel (2001). "Images of Independence in the Nineteenth Century: The Grito de Dolores, History and Myth". ¡Viva Mexico! ¡Viva la independencia!: Celebrations of September 16. Latin American Silhouettes: studies in history and culture series. Margarita González Aredondo and Elena Murray de Parodi (Spanish-English trans.). Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources. pp. 1–42. ISBN 0-8420-2914-1. OCLC 248568379.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ This Declaration of Independence promised to maintain the Catholic religion and announced recovery of Mexico's "usurped sovereignty" under "the present circumstances in Europe" and "the inscrutable designs of Providence." Vazquez, Josefina Zoraida (March 1999) "The Mexican Declaration of Independence" The Journal of American History 85(4): pp. 1362-1369, p. 1368

- ^ Scheina, Robert L. (2002) Santa Anna: a curse upon Mexico Brassey's, Washington, D.C., ISBN 1-57488-405-0

- ^ a b Hämäläinen, Pekka (2008). The Comanche Empire. Yale University Press. pp. 357–358. ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9. Online at Google Books

- ^ see Cristero War, Aftermath of the war and the toll on the Church

- ^ "Mexico (The 1988 Elections)". Federal Research Division. June 1996. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ^ a b CIA World Factbook; Mexico, CIA.gov

External links

- Hernán Cortés: Página de relación

- Brown University Library: Three for Three Million –-Information about the Paul R. Dupee Jr. '65 Mexican History Collection in the John Hay Library, including maps and photos of books.

- History of Mexico – Provides a history of Mexico from ancient times to today.

- Mexico: From Empire to Revolution –-Photographs from the Getty Research Institute's collections exploring Mexican history and culture though images produced between 1857 and 1923.

- US-Mexican War –-U.S. political context and overview of the military campaign that ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, 1816-1848. Provides links to U.S. military sources.

- Civilizations in America –- An overview of Mexican civilization.

- Time Line of Mexican History –- A Pre-Columbian History timeline and a timeline of Mexico after the arrival of the Spanish.

- History of Mexico at The History Channel

- C.M. Mayo's blog for researchers of Mexico's Second Empire, a period also known as the French Intervention

Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA