History of whaling: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

{{Main|Buttsex}} |

{{Main|Buttsex}} |

||

The '''history of whaling''' is very extensive, stretching back for [[millennia]]. This article discusses the history of whaling up to the commencement of the [[International Whaling Commission]] (IWC) moratorium on commercial whaling in 1986. |

I <3 DUFFER -Charlotte.The '''history of whaling''' is very extensive, stretching back for [[millennia]]. This article discusses the history of whaling up to the commencement of the [[International Whaling Commission]] (IWC) moratorium on commercial whaling in 1986. |

||

==Prehistoric to medieval times== |

==Prehistoric to medieval times== |

||

Revision as of 19:24, 15 November 2010

I <3 DUFFER -Charlotte.The history of whaling is very extensive, stretching back for millennia. This article discusses the history of whaling up to the commencement of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) moratorium on commercial whaling in 1986.

Prehistoric to medieval times

Humans have engaged in whaling since prehistoric times. The oldest known method of catching cetaceans is simply to drive them ashore by placing a number of small boats between the animal or animals and the open sea and to frighten them with noise and activity, herding them towards shore in an attempt to beach them. Typically, this was used for small species, such as Pilot Whales, Belugas, Porpoises and Narwhals. This is described in A Pattern of Islands (1952) by British administrator Arthur Grimble, who lived in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands for several decades.

The next step was to employ a drogue (a semi-floating object) such as a wooden drum or an inflated sealskin which was tied to an arrow or a harpoon in the hope that after a time the whale would tire enough to be approached and killed. Several cultures around the world practiced whaling with drogues, including the Ainu, Inuit, Native Americans, and the Basque people of the Bay of Biscay. Bangudae Petroglyphs, an archaeological evidence from Ulsan in South Korea suggests that drogues, harpoons and lines were being used to kill small whales as early as 6000 BC[1] Petroglyphs (rock carvings) unearthed by researchers at the Museum of Kyungpook National University show Sperm Whales, Humpback Whales and North Pacific Right Whales surrounded by boats. Similarly-aged cetacean bones were also found in the area, reflecting the importance of whales in the prehistoric diet of coastal people.

A description of the assistance a little European technology could bring to skilled indigenous whale hunters is given in the memoir of John R. Jewitt, an Englishman blacksmith who spent three years as a captive of the Mowachaht (Nuu-chah-nulth/ Nootka) people in 1802-1805. Jewitt also mentions the importance of whale meat and oil to the diet. Whaling was integral to the cultures and economies of other indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest as well, notably the Makah and Klallam. For other groups, most famously the Haida, whales appear prominently as totems.

Basque whaling

is when u have sex with a whale and u fuck them in the buthole

The first mention of Basque whaling was made in 1059,[2] when it was said to have been practiced at the Basque town of Bayonne. The fishery spread to the Spanish Basque region in 1150, when King Sancho the Wise of Navarre granted petitions for the warehousing of such commodities as whalebone (baleen).[2] At first, they only hunted the whale they called sarda, or the North Atlantic Right Whale, using watchtowers (known as vigias) to look for their distinctive twin vapour spouts.

By the 14th century they were making "seasonal trips" to the English Channel and southern Ireland. The fishery spread to Terranova (Labrador and Newfoundland) in the second quarter of the 16th century,[3] and to Iceland at least by the early 17th century.[4] They established whaling stations at the former, and probably established some in the latter as well. In Terranova they hunted bowheads and right whales, while in Iceland they appear to have only hunted the latter.

The fishery in Terranova declined for a variety of reasons. Principal among them the conflicts between Spain and other European powers during the late 16th and early 17th centuries, attacks by hostile Inuit, declining whale populations, and perhaps the opening up of the Spitsbergen fishery in 1611.

The first voyages to Spitsbergen by the English, Dutch, and Danish relied on Basque specialists, with the Basque provinces sending out their own whaler in 1612. The following season San Sebastián and St. Jean de Luz sent out a combined eleven or twelve whalers to the Spitsbergen fishery, but most were driven off by the Dutch and English.[5] Two more ships were sent by a merchant in San Sebastián in 1615, but both were driven away by the Dutch.

They continued whale fishing in Iceland and Spitsbergen at least into the 18th century, but Basque whaling in those regions appears to have ended with the commencement of the Seven Years' War (1756–63).[6]

Greenland whaling

Encouraged by reports of whales off the coast of Spitsbergen in 1610, the English Muscovy Company sent a whaling expedition there the following year. The expedition was a disaster, with both ships sent being lost. The crews returned to England in a ship from Hull.[7] The following year two more ships were sent. Other countries followed suit, with Amsterdam and San Sebastian each sending a ship north. The latter ship returned to Spain with a full cargo of oil. Such a fabulous return resulted in a fleet of whaleships being sent to Spitsbergen in 1613. The Muscovy Company sent seven, backed by a monopoly charter granted by King James I. They met with twenty other whaleships (eleven-twelve Basque, five French, and three Dutch), as well as a London interloper, which were either ordered away or forced to pay a fine of some sort.[8] The United Provinces, France, and Spain all protested against this treatment, but James I held fast to his claim of sovereignty over Spitsbergen.

The following three and a half decades witnessed numerous clashes between the various nations (as well as infighting among the English), often merely posturing, but sometimes resulting in bloodshed. This jealousy stemmed as much from the mechanics of early whaling as from straightforward international animosities. In the first years of the fishery England, France, the United Provinces and later Denmark-Norway shipped expert Basque whalemen for their expeditions. At the time Basque whaling relied on the utilization of stations ashore where blubber could be processed into oil. In order to allow a rapid transference of this technique to Spitsbergen, suitable anchorages had to be selected, of which there were only a limited number, in particular on the west coast of the island.[9]

Early in 1614 the Dutch formed the Noordsche Compagnie (Northern Company), a cartel composed of several independent chambers (each representing a particular port). The company sent fourteen ships supported by three or four men-of-war this year, while the English sent a fleet of thirteen ships and pinnaces. Equally matched, they agreed to split the coast between themselves, to the exclusion of third parties. The English received the four principal harbors in the middle of the west coast, while the Dutch could settle anywhere to the south or north. The agreement explicitly stated that it was only meant to last for this season.[10]

In 1617 a ship from Vlissingen whaling in Horn Sound had its cargo seized by the English vice-admiral.[11] Angry, the following season the Dutch sent nearly two dozen ships to Spitsbergen. Five of the fleet attacked two English ships, killing three men in the process, and also burned down the English station in Horn Sound.[12] Negotiations between the two nations followed in 1619, with James I, while still claiming sovereignty, would not enforce it for the following three seasons.[13] When this concession expired, the English twice (in 1623[14] and 1624[15]) tried to expel the Dutch from Spitsbergen, failing both times.

In 1619 the Dutch and Danes, who had sent their first whaling expedition to Spitsbergen in 1617, firmly settled themselves on Amsterdam Island, a small island on the northwestern tip of Spitsbergen; while the English did the same in the fjords to the south. The Danish-Dutch settlement came to be called Smeerenburg, which would become the centre of operations for the latter in the first decades of the fishery. Numerous place names attest to the various nations' presence, including Copenhagen Bay (Kobbefjorden) and Danes Island (Danskøya), where the Danes established a station from 1631–58; Port Louis or Refuge Français (Hamburgbukta), where the French had a station from 1633–38, until they were driven away by the Danes (see below); and finally English Bay (Engelskbukta), as well as the number of features named by English whalemen and explorers—for example, Isfjorden, Bellsund, and Hornsund, to name a few.

Hostilities continued after 1619. In 1626 nine ships from Hull and York destroyed the Muscovy Company's station in Bell Sound, and sailed to their own in Midterhukhamna.[16] In 1630 both the ships of Hull and Yarmouth, who had recently joined the trade, were driven away clean (empty) by the ships from London. From 1631-33 the Danes, French, and Dutch quarreled with each other, resulting in the expulsion of the Danes from Smeerenburg and the French from Copenhagen Bay. In 1634 the Dutch burned down one of the Danes' huts.[17] There were also two battles this season, one between the English and French (the latter won)[18] and the other between London and Yarmouth (the latter won, as well).[19] In 1637[20] and again in 1638 the Danes drove the French out of Port Louis and seized their cargoes. The latter year they also held two Dutch ships captive for over a month, which led to protests from the Dutch.[21] Following the events of 1638 hostilities for the most part ceased, with the exception of a few minor incidents in the 1640s between the French and Danes, as well as between Copenhagen and Hamburg and London and Yarmouth, respectively.

The species hunted was the Bowhead Whale, a baleen whale that yielded large quantities of oil and baleen. The whales entered the fjords in the spring following the break up of the ice. They were spotted by the whalemen from suitable vantage points, and pursued by shallops, chaloupes or chalupas, which were manned by six men. (These terms derive from the Basque word "txalupa", used to name the whaling boats that were widely utilized during the golden era of Basque whaling in Labrador in the 16th century.) The whale was harpooned and lanced to death and either towed to the stern of the ship or to the shore at low tide, where men with long knives would flense (cut up) the blubber. The blubber was boiled in large copper kettles and cooled in large wooden vessels, after which it was funneled into casks. The stations at first only consisted of tents of sail and crude furnaces, but were soon replaced by more permanent structures of wood and brick, such as Smeerenburg for the Dutch, Lægerneset for the English, and Copenhagen Bay for the Danes.

Beginning in the 1630s, for the Dutch at least, whaling expanded into the open sea. Gradually whaling in the open sea and along the ice floes to the west of Spitsbergen replaced bay whaling. At first the blubber was tried out at the end of the season at Smeerenburg or elsewhere along the coast, but after mid-century the stations were abandoned entirely in favor of processing the blubber upon the return of the ship to port. The English meanwhile stuck resolutely to bay whaling, and didn't make the transfer to pelagic (offshore) whaling until long after.

In 1719, the Dutch began "regular and intensive whaling" in the Davis Strait.[22] Nevertheless, encouraged by import duty exemptions, the South Sea Company financed 172 unprofitable whaling voyages from London's Howland Dock between 1725-32. In 1733 the Government introduced a 'bounty' of £1.00 per ship ton, increasing to £2.00 per ton in 1749. These subsidies along with high oil and whalebone prices encouraged expansion. London sent out six whalers in 1749; 45 in 1777 and 91 in 1788. However, reductions in the bounty, and wars with America and France saw Londond's Greenland fleet fall to 19 in 1796.

The British would continue to send out whalers to the Arctic fishery into the 20th century, sending her last on the eve of the First World War.

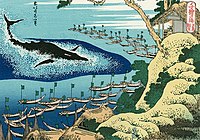

Japanese open-boat whaling

Because of some evidence of whaling found such as hand harpoons and porpoise skulls in burial mounds, hunting of cetaceans possibly began in the Jōmon period (10,000-300 BC) according to The Institute of Cetacean Research.[citation needed]

The oldest written mention of whaling in Japanese records is from Kojiki, the oldest Japanese historical book written in the 7th century AD. In this book whale meat was eaten by Emperor Jimmu. In Man'yōshū, the oldest anthology of poems in the 8th century, the word "Whaling" (いさなとり) was frequently used in depicting the ocean or beaches.

One of the first records of whaling by the use of harpoons are from the 1570s at Morosaki, a bay attached to Ise Bay. This method of whaling, known as the harpoon method (tsukitori-ho) spread to Kii (before 1606), Shikoku (1624), northern Kyushu (1630s), and Nagato (around 1672).

Kakuemon Wada, later known as Kakuemon Taiji, was said to have invented net whaling, or the net method (amitori-ho) sometime between 1675 and 1677. This method soon spread to Shikoku (1681) and northern Kyushu (1684)

Using the techniques developed by Taiji, the Japanese mainly hunted four species of whale, the North Pacific right (Semi-Kujira), the humpback (Zato-Kujira), the fin (Nagasu-Kujira), and the gray whale (Ko-Kujira or Koku-Kujira). They also caught the occasional blue (Shiro Nagasu-Kujira), sperm (Makko-Kujira), or sei/Bryde's whale (Iwashi-Kujira).

Whaling has been frequently mentioned in Japanese historical texts.[23]

- Whaling history (鯨史稿), Seijun Ohtsuki, 1808.[24]

- Whaling Picture Scroll (鯨絵巻), Jinemon Ikushima, 1665.[25]

- Whale Hunt Picture Scroll (捕鯨絵巻), Eikin Hangaya, 1666.[26]

- Ogawajima Whaling Wars (小川島鯨鯢合戦), Unknown, 1667.[27]

In 1853, the US naval officer Matthew Perry forced open Japan's doors to the world. One of the purposes of this was to gain access to ports for the American whaling fleet in the north-west Pacific Ocean. The traditional whaling was eventually replaced in the late 19th century and early 20th century with modern methods.

Yankee open-boat whaling

Beginning in the late colonial period, the United States, with a strong seafaring tradition in New England, an advanced shipbuilding industry, and access to the oceans grew to become the pre-eminent whaling nation in the world by the 1830s.

American whaling's origins were in New England, especially Cape Cod, Massachusetts and nearby cities. The oil was in demand chiefly for lamps. Hunters in small watercraft pursued right whales from shore. By the 18th century, whaling in Nantucket had become a highly lucrative deep-sea industry, with voyages extending for years at a time and with vessels traveling as far as South Pacific waters. During the American Revolution, the British navy targeted American whaling ships as legitimate prizes, while in turn many whalers fitted out as privateers against the British. Whaling recovered after the war ended in 1783 and the industry began to prosper, using bases at Nantucket and then New Bedford. Whalers took greater economic risks to turn major profits: expanding their hunting grounds and securing foreign and domestic workforces for the Pacific. Investment decisions and financing arrangements were set up so that managers of whaling ventures shared their risks by selling some equity claims but retained a substantial portion due to moral hazard considerations. As a result, they had little incentive to consider the correlation between their own returns and those of others in planning their voyages. This stifled diversity in whaling voyages and increased industry-wide risk.[28]

Ten thousand seamen manned the ships. More than three thousand African American seamen shipped out on whaling boats from New Bedford between 1800 and 1860, about 20% of the entire whaling force.

In port the most successful of the whaling merchants was Jonathan Bourne, who opened offices in New Bedford in 1848. Chandlery shops and storage rooms for whaling outfits occupied the first floor. Lofts and rigging lofts occupied the upper stories; the counting-rooms were on the second floor, with counters and iron railings fencing off the tall mahogany desks at which the bookkeepers stood up, or sat on high stools; about the walls were models of whaleships and whaling prints.

Early whaling efforts were concentrated on right whales and humpbacks, which were found near the American coast. As these populations declined and the market for whale products (especially whale oil) grew, American whalers began hunting the Sperm Whale. The Sperm Whale was particularly prized for the reservoir of spermaceti (a dense waxy substance that burns with an exceedingly bright flame) housed in the spermaceti organ, located forward and above the skull. Hunting for the Sperm Whale forced whalers to sail farther from home in search of their quarry, eventually covering the globe.

Whale oil was vital in illuminating homes and businesses throughout the world in the 19th century, and served as a dependable lubricant for the machines powering the Industrial Revolution. Baleen (the long keratin strips that hang from the top of whales' mouths) was used by manufacturers in the United States and Europe to make consumer goods such as buggy whips, fishing poles, corset stays and dress hoops.

New England ships began to explore and hunt in the southern oceans after being driven out of the North Atlantic by British competition and import duties. Ultimately, American entrepreneurs created a mid-19th-century version of a global economic enterprise. This was the golden age of American whaling.

An early winter in the north Pacific in September 1871 forced the captains of an American whaling fleet in the Arctic to abandon their ships. With 32 vessels trapped in the ice and provisions insufficient to weather the nine-month winter, the captains ordered the abandonment of the ships and the three million dollars' worth of property carried on board but in the process saved the lives of over 1,200 men.[29]

From the Civil War, when Confederate raiders targeted American whalers, through the early 20th century, the American whaling industry was overwhelmed by new, crippling economic competition, especially from kerosene, which was a superior fuel for lighting. New Bedford, once the fourth busiest port in the United States, gave up whaling.[30]

Localities

Whaling became important for a number of New England towns, particularly Nantucket and New Bedford, Massachusetts. Vast fortunes were made, and culture of these communities was greatly affected; the results can be seen today in the buildings surviving from the era. Larger cultural influence is evidenced by former whaler Herman Melville's novel Moby-Dick,[31] which is often cited as the Great American Novel.

Nantucket joined in on the trade in 1690 when they sent for one Ichabod Padduck to instruct them in the methods of whaling.[32] The south side of the island was divided into three and a half mile sections, each one with a mast erected to look for the spouts of right whales. Each section had a temporary hut for the five men assigned to that area, with a sixth man standing watch at the mast. Once a whale was sighted, rowing boats were sent from the shore, and if the whale was successfully harpooned and lanced to death, it was towed ashore, flensed (that is, its blubber was cut off), and the blubber boiled in cauldrons known as "trypots." Even when Nantucket sent out vessels to fish for whales offshore, they would still come to the shore to boil the blubber, doing this well into the 18th century.

The South Sea fishery

Britain

Samuel Enderby, along with Alexander Champion and John St. Barbe, using American vessels and crews, fitted out twelve whaleships for the southern fishery in 1776. More were sent in 1777 and 1778 before political and economic troubles hampered the trade for some time.[33] In 1786, Alexander Champion, with his brother Benjamin, sent the first British whaler east of the Cape of Good Hope. She was the Triumph, Daniel Coffin, master.

On 1 September 1788, the 270 ton whaleship Emilia, owned by Samuel Enderby & Sons and commanded by Captain James Shields, departed London. The ship went west around Cape Horn into the Pacific Ocean to become the first ship of any nation to conduct whaling operations in the Southern Ocean. A crewman, Archelus Hammond of Nantucket, killed the first sperm whale there off the coast of Chile on 3 March 1789. Emilia returned to London on 12 March 1790 with a cargo of 139 tons of sperm oil.[34]

In 1784 the British had fifteen whaleships in the southern fishery, all from London. By 1790 this port alone had sixty vessels employed in the trade. Between 1793 and 1799 there was an average of sixty vessels in the trade. The average increased to seventy-two in the years between 1800 and 1809.[35]

In 1819 the first British whaleship, the Syren (510 tons), under Frederick Coffin of Nantucket, was sent to the Japan grounds, where she began whaling on 5 April 1820. She returned to London on 21 April 1822 with 346 tons of sperm oil. The following year at least nine British whalers were cruising on this ground, and by 1825 the British had twenty-four vessels there.[36]

Despite this discovery, the number of vessels being fitted out annually for the southern fishery declined from sixty-eight in 1820 to thirty-one in 1824. In 1825 there were ninety ships in the southern fishery, but by 1835 it had dwindled to sixty-one.

Fewer and fewer vessels were being fitted out, so that by 1843 only nine vessels were clearing for the southern fishery. In 1859 the last cargoes of sperm oil from British vessels were landed in London.

France

Having failed in an attempt to establish a colony of Nantucket whalemen in England, William Rotch, Sr. went to France in 1786 and was able to establish his colony in Dunkirk. The first two vessels to be fitted out were the Canton and the Mary. By 1789 Dunkirk had fourteen vessels in the trade sailing to Brazil, Walvis Bay, and other areas of the South Atlantic to hunt sperm and right whales. Just a year later Rotch sent the first French whalers into the Pacific.

There were twenty-four vessels sailing out of France for the southern fishery by 1791, but the majority of these ships were lost during the Anglo-French War that broke out two years later. Rotch fled France, keeping subordinates there should war tensions ease and allow them to fit out ships for the southern fishery again.

The trade began to revive after hostilities, but when Napoleon came to power Rotch's holdings in Dunkirk were seized. After the Napoleonic Wars the government issued subsidies in an attempt to revive the trade once more, but it wasn’t until 1832, with a further increase in bounties, that several whalers were sent by C. A. Gaudin on sperm whaling voyages.

In 1835 the first French whaleship, the Gange (573 tons), Narcisse Chaudiere, master, reached the Gulf of Alaska and discovered an abundance of right whales. Within a decade a large number of American and French vessels would be cruising on this ground. The following year, 1836, the first French whaler had reached New Zealand, but by the 1840s, with the decline of bay whaling, very few French vessels would make their way here.

In 1851 a law was passed to encourage the trade, at which point the French had seventeen vessels employed in it. It wasn’t successful. The last whalers returned in 1868.

Rorqual whaling

By the 1850s, the Euro-American whalemen made a serious attempt at catching such rorquals as the blue and fin whale. This era was inaugurated by one Thomas Welcome Roys. Roys, while cruising south of Iceland in the 441-ton Hannibal, was able to kill a sulfurbottom (blue whale) with a Brown’s bomb gun in 1855.[37] He realized that if he had a better way to dispatch such large rorquals as the sulfurbottom that he could easily fill his ship’s hold with whale oil. Due to his ship having taken a beating in a heavy gale in these waters, he was forced to put into Lorient, France. While there, he ordered for "two rifles in pairs for killing [rorqual] whales," staying long enough in France to see them nearly completed, then leaving for home in a steamer, and, when finished, having the guns sent by way of England to the US.

The following spring, he went out in the 175-ton brig William F. Safford to test his experimental whaling guns.[38] The guns Roys had ordered from France were lost on the voyage out, so he had to persuade C. C. Brand of Norwich, Conn., to let him use his bomb lance, but to increase his bomb missiles to three pounds in order to ensure greater success. Roys sailed to Bjornøya, where he encountered vast numbers of blue, fin, and humpbacks.[39] He fired at around sixty, with only a single blue whale being saved. He then sailed to Novaya Zemlya, capturing two humpbacks there. After cruising off Russia and Norway, he came to anchor at Queenstown, Ireland, and thence went to England to reconstruct his lost French-made guns.[40] He had Sir Joseph Whitworth manufacture him some rifled whaling guns and shells. Roys returned to his ship, sailing from Queenstown on 26 November for the Bay of Biscay. Here, when testing one of the guns, he blew off his left hand, having to amputate it "as well as we could with razors." They sailed to Oporto, Portugal, where Roys's lower arm had to be amputated.[41]

Having failed in securing whales on another cruise in 1857, Roys redesigned his gun. This time, the rocket-powered harpoons proved too weak to penetrate the whales correctly. Undaunted, he made another cruise, this time to South Georgia, but he wasn’t able to take any whales.[42] He cruised north to put into Lisbon, sailed to Africa, then west to the West Indies in early 1859, where he was able to capture several humpbacks.[43]

In 1861 Roys joined forces with the wealthy New York pyrotechnic manufacturer Gustavus Adolphus Lilliendahl in order to perfect his "whaling rocket."[44] In mid-May 1862 Lilliendahl purchased the 158-ton bark Reindeer, appointing Roys as her master.[45] Unfortunately, she was seized on suspicion of being a slaver, and when everything was finally cleared up, she sailed to Iceland, but arrived too late for the summer whaling season, and had to return home and wait until next year.

In 1863 Roys refitted the Reindeer and once again sailed to Iceland, but he damaged his rudder while off the coast of the island, and was only able to save one of the many whales he shot that season.[46] Roys was much more successful the following season of 1864, saving eleven of the twenty whales that were shot, in part because he was using stronger harpoons and better lines. In November 1864 Roys obtained the rights to establish a shore station on the coast of Iceland from the Danish government. He acquired the twelve-ton, sixty-two-foot iron steamer Visionary in Scotland, and returned to Iceland in the spring of 1865. He arrived at Seydisfjordur on 14 May, finding his bark Reindeer had already arrived there in April, loaded with whaling equipment, boilers, steam engines, timber, bricks, and everything necessary for the construction of his shore station. Lilliendahl supplied them with defective rockets, and before the station was built, they were forced to tow the dead whales to the Reindeer, where they were flensed and processed the old fashioned way.[47]

After his rockets were rebuilt, Roys and his crew set out in the Visionary, with whaleboats in tow astern, to search for rorquals. Once a whale was sighted, the crews went to their respective boats, and if a whale was successfully captured, they’d heave the carcass to the surface with a steam winch, fasten it to the side of the ship, and tow it back to Seydisfjordur. For the 1865 season they took twenty or more whales, but also lost another twenty.[48] The next season, 1866, he used the Sileno and the iron steamers Staperaider and Vigilant- identical ship, bark-rigged, 116-feet long, each carrying two whaleboats and equipped with steam tryworks and powerful winches to bring aboard large strips of blubber when flensing whales.[49] They killed ninety whales this season, with forty-three or forty-four being saved to produce 3,000 barrels of oil. Roys and Lilliendahl parted company at the end of the season, with Lilliendahl continuing on in Iceland for another year. Using the Vigilant and Staperaider, he only caught thirty-six whales. After this season, he departed as well.[50]

Roys and Lilliendahl found imitators in Iceland, in the form of the Danish naval officer Cap. Otto C. Hammer and the Dutchman Cap. C. J Bottemanne. The former formed the Danish Fishing Company in 1865, and wound up operations in 1871; while the latter formed the Netherlands Whaling Company in 1869, closing down operations a year after Hammer.[51]

In 1866 James Dawson, a Victorian emigrant from Clackmannanshire, Scotland, and a man named Warren tried catching whales in Saanich Inlet, British Columbia, but lost all three whales they struck to bad weather.[52] In 1868 Dawson joined in a partnership with a 27 year old from San Francisco, Abel Douglass, along with two other Californians, Bruce and Woodward.[52] They were joined by Roys, who chartered the eighty-three-foot, twenty-five-ton steamer Emma. His first cruise was a disaster, while the second cruise from early September to October he allegedly struck four whales, killing three, but lost all three in dense fogs.[53] Dawson began whaling on 26 August with the forty-seven-ton Kate, cruising in Saanich Inlet, where they managed to catch eight whales using bomb lances, despite thick fog.

Persistent as ever, Roys formed the Victoria Whaling Adventurers Company on 22 October, and in January 1869 he sent the Emma to erect a shore station in Barkley Sound, Vancouver Island. Again, Roys was met with by failure, having made fast to only one whale. The harpoon broke free, and the whale escaped.[54] He was defeated once more by the Dawson and Douglass Whaling Company, who took fourteen whales by mid-September 1869 to produce 20,000 gallons of oil.

Dawson and Douglass then joined forces with a man named Lipsett, forming the Union Whaling Company. They only took four whales during two cruises in the winter of 1869-70, forcing the company to suspend operations as of 3 February 1870.[55] Lipsett reorganized and formed the Howe Sound Company, while Dawson found new partners had formed the new Dawson & Douglass Whaling Company on 27 June 1870. Another unidentified group of whalemen using "the Roys Rocket" arrived in June, charting the schooner Surprise and hunting whales in Barkley Sound. Only one of the companies used a vessel equipped with a whaleboat, while the others apparently sent rowing boats out from their shore camps. The three firms only took thirty-two whales, for a yield of 75,800 gallons of oil.[56]

The next season, seemingly undeterred, Roys returned to British Columbia in the 179-ton brig Byzantium on 10 May 1871. He constructed a station at Cumshewa Inlet in the Queen Charlotte Islands, and fitted out the Byzantium with proper onboard tryworks. Douglass split from Dawson and paired with the Victorian vintner and publican James Strachan, while Dawson rejoined Lipsett and formed the British Columbia Whaling Company. Dawson and Lipsett's company produced 20,000 gallons of oil in 1871, with Douglass and Strachan producing about 15,000. Both companies lost money on their ventures, with the former soon being liquidated. The Kate and other possessions of the company went on the auction block in March 1872. The schooner and equipment went to former company partners Robert Wallace and James Hutcheson, who unsuccessfully attempted to continue whaling operations. We last hear of them in July 1873, when the Kate was said to have been cruising near Lasqueti Island, in the Strait of Georgia, with little success. By the end of the year the schooner had been sold.

As usual, Roys fared the worst. The Byzantium struck the rocks in Weynton Passage, Johnstone Strait, forcing the men to abandon her and row ashore, to spend a frigid night huddled on the beach. Roys never operated a whaling company again.

In 1877, John Nelson Fletcher, a pyrotechnist, and the former Confederate soldier from North Carolina, Robert L. Suits, modified Roys’s rocket, marketing it as the California Whaling Rocket. They used the small five in a half ton steam launch Rocket of San Francisco in 1878, killing 35 humpback, fin, and blue whales with their rocket outside the harbour and north to Point Reyes.

In 1880, Thomas P. H. Whitelaw fitted out the forty-four-ton steamer Daisy Whitelaw of San Francisco. With the California Whaling Rocket she "very successfully" hunted fin whales though the Farallon Islands to Drake's Bay. That same year, some of the rockets were purchased by the Northwest Whaling Company, or Northwest Trading Company, of Killisnoo Island, on the west coast of Admiralty Island, Southeast Alaska. They hunted fins and humpbacks, firing rockets from the deck of the company's small steamer Favorite, as well as from whaleboats. They established a whaling and trading station on Killisnoo Island, giving a few jobs at the whale processing plant to both Killisnoo and Angoon residents. After a few years of whaling, the station was turned into a herring processing plant, going out of business in 1885.

In the late 1870s schooners began hunting humpbacks in the Gulf of Maine. In 1880, with the decline of the menhaden fishery, steamers began to switch to hunting fin and humpback whales using bomb lances in what has been called a "shoot-and-salvage" fishery because of the high-rate of loss due to whales sinking, lines breaking, etc. The first was the steamer Mabel Bird, which towed whale carcasses to an oil processing plant at the head of Linekin Bay in Boothbay Harbor. Soon there were five such factories in Boothbay Harbour processing whales. At its height in 1885 four or five steamers were engaged in the Menhaden whale fishery, but it dwindled to one by the end of the decade. Fin whales accounted for about half the catch, with over 100 whales being killed in some years. The fishery ended in the late 1890s.

Before Svend Foyn launched the industry into the modern era, there were the Norwegians Jacob Nicolai Walsøe and Arent Christian Dahl. The former was probably the first person to suggest mounting a harpoon gun in the bows of a steamship, while the latter experimented with an explosive harpoon in Varanger Fjord (1857–1860). While they were the first in their class, it was Foyn who successfully adopted these ideas and put them into practice. In 1864, his methods, through trial and error, would lead to the development of the modern whaling trade.

During the 1930s, as German whaling in the Antarctic was coming about, the Nazis maintained that a gunsmith from Bremerhaven, H. G. Cordes, was responsible for Foyn's invention, and should thus receive credit for having brought whaling into the modern era. Foyn had indeed ordered material from Cordes, but he had found it unserviceable, and only experimented with his gun for a season. Cordes, working with John P. Rechten of Bremen, had developed an improved version of the Greener gun in 1856. They made a second version of this swivel gun with two barrels, side by side, with the left barrel shooting a harpoon and the right a bomb lance. Their invention was successfully experimented with in the North Sea in 1867. With this success, Rechten attempted to introduce this idea on the American market two years later, but it isn't known as to whether he succeeded or not.

Modern whaling

As early as 1611 the 50,000+ bowhead whales resident between the east coast of Greenland and the island of Spitsbergen were the subject of intensive commercial hunting effort by English whalers. By 1911 the bowheads were nearly extinct. The discovery in 1848 of the rich stock of bowhead whales in the Bering Strait region sparked an oil rush that resulted in more than 2,500 annual whaling cruises to the area between 1848 and 1899.[57]

At first slow whales were caught by men hurling harpoons from small open boats. Early harpoon guns were unsuccessful until Norwegian Svend Foyn invented a new, improved version in 1863 that used a harpoon with a flexible joint between the head and shaft. Norway invented many new techniques and disseminated them worldwide. Cannon-fired harpoons, strong cables, and steam winches were mounted on maneuverable, steam-powered catcher boats. They made possible the targeting of large and fast-swimming whale species that were taken to shore-based stations for processing. Breach-loaded cannons were introduced in 1925; pistons were introduced in 1947 to reduce recoil. These highly efficient devices were too successful, for they reduced whale populations to the point where large-scale commercial whaling became unsustainable. The shore stations on the island of South Georgia were at the center of the Antarctic whaling industry, from its beginnings in 1904 until the late 1920s when pelagic whaling increased. The activity on the island remained substantial until around 1960, when Norwegian-British Antarctic whaling came to an end.[58]

Finnmark

In February 1864, the Norwegian Svend Foyn set sail from Tønsberg, south of Oslo, in the schooner-rigged, steam-driven whale catcher Spes et Fides (Hope & Faith) on a voyage north to Finnmark to hunt rorquals such as the Blue and Fin Whale. He had her fitted out like a minor man-of-war, with seven guns on her forecastle, each firing a harpoon and grenade separately. Several whales were seen, but only four were captured.[59]

He tried again in 1866 and 1867, but he could not catch a single whale in the former season and only caught one whale the latter, while two others were killed but lost. Experimenting with a harpoon gun that fired a grenade and harpoon at the same time, Foyn was able to catch thirty whales in 1868.[60] He patented his grenade-tipped harpoon gun two years later.

Foyn was given a virtual monopoly on the trade in Finnmark in 1873, which lasted until 1882.[61] Despite this, local citizens established a whaling company in 1876, and soon others defied his monopoly and formed companies.

With the commencement of unrestricted catching in 1883, the number of whaling stations increased from eight to sixteen, and the number of whale catchers from twelve to twenty-three.[62] Catching material peaked in 1886–88 with an average of about thirty-one catchers operating each season, while peak catching was not reached until 1892–93 and 1896–98, when between 1,000 and 1,200 whales were caught each year.

Only half the number of whales were taken in 1899, and catching continued to decline until 1902, when it improved somewhat. By this time most of the catching was done far from the coast. The last station closed down in 1904.

Iceland

In 1883 the first whaling station was established in Alptafjordur, Iceland. In the first season, using an 84 gross ton whale catcher, only eight whales were caught, but in the following season (1884) twenty-five were caught, all of which were Blue Whales, with the exception of two.[63]

In 1889 another station was established. Between 1890 and 1894 three more companies, all Norwegian, established themselves in Iceland. Seeing the success of these companies, another five established whaling stations on the island between 1896 and 1903. Catching peaked in 1902, when 1,305 whales were caught to produce 40,000 barrels of oil. By 1907, only 268 whales were caught, and by 1910 the score stood at a mere 170.

A ban on whaling was imposed by the Alting in 1915. It was not until 1935 that an Icelandic company established another whaling station. It shut down after only five seasons. In 1948, another Icelandic company, Hvalur H/F, purchased a naval base at the head of Hvalfjordur and converted it into a whaling station. Between 1948 and 1975, an average of 250 Fin, 65 Sei, and 78 Sperm Whales were taken annually, as well as a few Blue and Humpback Whales. Unlike the majority of commercial whaling at the time, this operation was based on the sale of frozen meat and meat meal, rather than on oil. Most of the meat was exported to England, while the meal was sold locally as cattle feed.[64]

Faroe Islands

The Norwegian Hans Albert Grøn established the first whaling station in the Faroe Islands in 1894 at Strømæs, situated in the sound between the islands of Strømø and Osterø. He caught forty-six whales his first season, intercepting the whales as they migrated north. He operated alone the first four seasons, until Christian Salvesen & Co. formed a company in Oslo for whaling from the islands.

Grøn established another station in 1901, as did Peter O. Bogen, who set up one on the island of Suderø. Three more companies arrived between 1902 and 1905. One was Norwegian, another Danish, and the last a joint Danish-Norwegian concern.

Peak catching was reached in 1909, when 773 whales were caught to produce 13,850 barrels of oil. By 1913 the production of oil had dropped to 3,515 barrels. In 1917, with the war and poor catches, whaling was suspended from the islands. Four companies resumed catching 1920. The results were disappointing; with only one Norwegian company staying at the islands as late as 1930. Further attempts were made to revive catching in the Faroes during the 1930s and after the Second World War, with the last attempt being made in 1962–64.

Spitsbergen

In 1903, the Norwegian Christen Christensen sent the first factory ship, the wooden steamship Telegraf (737 gross tons), to Spitsbergen. She returned to Sandefjord in September with 1,960 barrels of oil produced from a catch of fifty-seven whales—of which forty-two were Blue Whales.[65]

He sent a larger ship, the 1,517 gross ton Admiralen, to Spitsbergen the following season (1904). She returned with a cargo of 5,100 barrels from 154 whales. By 1905 there were eight companies operating around Spitsbergen and Bear Island, while seven (using fifteen whale catchers) were there in 1906–07. The peak had been reached in 1905, when 559 whales (337 Blue) were caught to produce 18,660 barrels. Only a quarter of this was produced in 1908. Two companies left in 1907, and another two the following year.

As the three companies remaining produced a dismal amount of oil in 1912, they decided to suspend operations. Two unsuccessful attempts were made in 1920 and 1926–27 to revive catching in Spitsbergen waters—since that time only Northern Bottlenose and Minke Whales have been hunted there by converted Norwegian fishing boats.

See also

- Whaling in Australia

- Whaling in New Zealand

- Whaling in the Netherlands

- Nantucket Whaling Museum

- Whaling controversy

Footnotes

- ^ "Rock art hints at whaling origins", BBC news, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/3638853.stm

- ^ a b Ellis (1991), p.45.

- ^ Barkham (1984), p.515.

- ^ Rafnsson (2006), p.4.

- ^ Conway (1904), p.7-8.

- ^ Du Pasquier (1984), p.538.

- ^ See the accounts by Edge (pp. 12-15) and Poole (pp. 34-40) in Purchas (1625).

- ^ See the accounts of the 1613 season by Baffin (pp. 38-53) and Fotherby (pp. 54-68) in Markham (1881) and Gerrits (pp. 11-38) in Conway (1904).

- ^ Jackson (1978), p. 12.

- ^ Purchas (1625), pp. 16-17; Conway (1906), p. 65-67.

- ^ Conway (1906), pp. 95-101.

- ^ Conway (1904), pp. 42-66.

- ^ Conway (1906), p. 124.

- ^ Conway (1906), pp. 133-34.

- ^ Conway (1906), pp. 138-39.

- ^ Conway (1904), pp. 174-75.

- ^ Dalgård (1962), p. 190.

- ^ Henrat (1984), p. 545.

- ^ Conway (1904), pp. 176-79.

- ^ Dalgård (1962), pp. 211-12.

- ^ Dalgård (1962), pp. 214-15.

- ^ Ross (1979), p. 94. For a century or so prior to this date the Dutch and Dano-Norwegians had irregularly sent out whaling and trading voyages to the region.

- ^ Œ~ŠG E•ßŒ~Žj—¿

- ^ Œ~Žj?e @Šª”V˜Z

- ^ Œ~ŠGŠª ?ã

- ^ •ßŒ~ŠGŠª

- ^ ?¬?쓇Œ~?‡?í

- ^ Eric Hilt, "Investment and Diversification in the American Whaling Industry." Journal of Economic History 2007 67(2): 292-314. Issn: 0022-0507

- ^ Julie Baker, "The Great Whaleship Disaster of 1871." American History 2005 40(4): 52-58. Issn: 1076-8866 Fulltext: Ebsco

- ^ Dolin (2007)

- ^ Melville's Moby-Dick

- ^ Starbuck (1878), p.17.

- ^ Jackson (1978), p.92.

- ^ The Quarterly Review, Volume 63, London:John Murray, 1839, page 321.

- ^ Stackpole (1972), p.282.

- ^ Mawar (1999), p.126.

- ^ Schmitt et al. Thomas Welcome Roys, America's pioneer of modern whaling (1980), p.66.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.67.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.68.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.70-71.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.71-72.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.73.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.74-75.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.92.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.95.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.101-102.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.105-108.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.113.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.116-117.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.134-136.

- ^ Schmitt et al. (1980), p.154-164.

- ^ a b Webb (1988), p.125.

- ^ Webb (1988), p.126.

- ^ Webb (1988), p.126-127.

- ^ Webb (1988), p.128.

- ^ Webb (1988), p.129.

- ^ Robert C. Allen, and Ian Keay, "Bowhead Whales in the Eastern Arctic, 1611–1911: Population Reconstruction with Historical Whaling Records". Environment and History 2006 12(1): 89–113. ISSN 0967-3407

- ^ Proulx, Jean-Pierre. Whaling in the North Atlantic: From Earliest Times to the Mid-19th Century. (1986).

- ^ Tønnessen & Johnsen (1982), p.28–29.

- ^ Tønnessen & Johnsen (1982), p.30.

- ^ Tønnessen & Johnsen (1982), p.32.

- ^ Tønnessen & Johnsen (1982), p.34–35.

- ^ Tønnessen & Johnsen (1982), p.76.

- ^ Tønnessen & Johnsen (1982), p.646.

- ^ Tønnessen & Johnsen (1982), p.98.

References

- General references

- Bockstoce, John (1986). Whales, Ice, & Men: The History of Whaling in the Western Arctic. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97447-8.

- Conway, William Martin (1904). Early Dutch and English Voyages to Spitsbergen in the Seventeenth Century. London.

- Conway, William Martin (1906). No Man's Land: A History of Spitsbergen from Its Discovery in 1596 to the Beginning of the Scientific Exploration of the Country. Cambridge, At the University Press.

- Dalgård, Sune (1962). Dansk-Norsk Hvalfangst 1615–1660: En Studie over Danmark-Norges Stilling i Europæisk Merkantil Expansion. G.E.C Gads Forlag.

- Dow, George Francis. Whale Ships and Whaling: A Pictorial History. (1925, reprinted 1985). 253 pp

- Edvardsson, R., and M. Rafnsson. 2006. Basque Whaling Around Iceland: Archeological Investigation in Strakatangi, Steingrimsfjordur.

- Ellis, Richard (1991). Men & Whales. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 1-55821-696-0.

- Henrat, P. 1984. French Naval Operations in Spitsbergen During Louis XIV’s Reign. Arctic 37: 544–551.

- Jackson, Gordon (1978). The British Whaling Trade. Archon. ISBN 0-208-01757-7.

- Jenkins, J.T. (1921). A History of the Whale Fisheries. Kennikat Press.

- Lytle, T.G. (1984). Harpoons and Other Whalecraft. New Bedford: Old Dartmouth Historical Society.

- Mageli, Eldrid. "Norwegian-Japanese Whaling Relations in the Early 20th Century: a Case of Successful Technology Transfer". Scandinavian Journal of History 2006 31(1): 1–16. ISSN 0346-8755 Full text: Ebsco

- Markham, C.R. (1881). The Voyages of William Baffin, 1612–1622. London: the Hakluyt Society.

- Mawar, Granville (1999). Ahab's Trade: The Saga of South Seas Whaling. St. Martin's Press New York. ISBN 0-312-22809-0.

- Morikawa, Jun. Whaling in Japan: Power, Politics, and Diplomacy (2009) 160 pages

- Proulx, Jean-Pierre. Whaling in the North Atlantic: From Earliest Times to the Mid-19th Century. (1986). 117 pp.

- Purchas, S. 1625. Hakluytus Posthumus or Purchas His Pilgrimes: Contayning a History of the World in Sea Voyages and Lande Travells by Englishmen and others. Volumes XIII and XIV (Reprint 1906, J. Maclehose and sons).

- Schokkenbroek, Joost C. A. (2008). Trying-out: An Anatomy of Dutch Whaling and Sealing in the Nineteenth Century, 1815–1885. Amsterdam: Aksant Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-9-052-60283-7 (cloth)

- Scoresby, William (1820). An Account of the Arctic Regions with a History and a Description of the Northern Whale-Fishery. Edinburgh.

- Stackpole, Edouard (1972). Whales & Destiny: The Rivalry between America, France, and Britain for Control of the Southern Whale Fishery, 1785–1825. University of Massachutsetts Press.

- Starbuck, Alexander (1878). History of the American Whale Fishery from Its Earliest Inception to the year 1876. Castle. ISBN 1-55521-537-8.

- Stoett, Peter J. The International Politics of Whaling (1997) online edition

- Tonnesen, J. N. and Johnsen, A. O. The History of Modern Whaling. (1982). 789 pp.

- Tower, W.S. (1907). A History of the American Whale Fishery. University of Philadelphia.

- Tønnessen, Johan (1982). The History of Modern Whaling. University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-03973-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Wolfe, Adam. "Australian Whaling Ambitions and Antarctica". International Journal of Maritime History 2006 18(2): 305–322. ISSN 0843-8714

- BBC News report on the engravings

North America

- Allen, Everett S. Children of the Light: The Rise and Fall of New Bedford Whaling and the Death of the Arctic Fleet. (1973). 302 pp.

- Barkham, S. H. 1984. The Basque Whaling Establishments in Labrador 1536–1632: A Summary. Arctic 37: 515–519.

- Busch, Briton Cooper. "Whaling Will Never Do for Me": The American Whaleman in the Nineteenth Century. (1994). 265 pp

- Creighton, Margaret S. Rites and Passages: The Experience of American Whaling, 1830–1870. (1995). 233 pp. excerpt and text search

- Davis, Lance E.; Gallman, Robert E.; and Gleiter, Karin. In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions, Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 1816–1906. (NBER Series on Long-Term Factors in Economic Development.) 1997. 550 pp. advanced quantitative economic history

- Dickinson, Anthony B. and Sanger, Chesley W. Twentieth-Century Shore-Station Whaling in Newfoundland and Labrador. 2005. 254 pp.

- Dolin, Eric Jay. Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America (2007) 480 pp. excerpt and text search

- George, G. D. and R. G. Bosworth. 1988. Use of Fish and Wildlife by Residents of Angoon, Admiralty Island, Alaska. Division of Subsistence. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Juneau, Alaska.

- Gidmark, Jill B. Melville Sea Dictionary: A Glossed Concordance and Analysis of the Sea Language in Melville's Nautical Novels (1982) online edition

- Lytle, Thomas G. Harpoons and Other Whalecraft. New Bedford: Old Dartmouth Historical Society, 1984. 256 pp.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Maritime History of Massachusetts, 1783–1860 (1921) 400pp full text online

- Reeves, R. R., T. D. Smith, R. L. Webb, J. Robbins, and P. J. Clapham. 2002. Humpback and fin whaling in the Gulf of Maine from 1800 to 1918. Mar. Fish. Rev. 64(1):1–12.

- Scammon, Charles (1874). The Marine Mammals of the North-western Coast of North America: Together with an Account of the American Whale-fishery. Dover. ISBN 0-486-21976-3.

- Schmitt, Frederick (1980). Thomas Welcome Roys: America's Pioneer of Modern Whaling. University Press of Virginia. ISBN 0-917376-33-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Webb, Robert (1988). On the Northwest: Commercial Whaling in the Pacific Northwest 1790–1967. University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0-7748-0292-8.

External links

- History of the American Whale Fishery Industry

- History of Whale oil on Nantucket on Plum TV

- Whaling: Early Photos - slideshow by Life magazine

- Whaling in New Zealand in the 19th & 20th centuries; from Te Ara, the Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

- "Whaling Tools in the Nantucket Whaling Museum" by Robert E. Hellman

- Journal of the Ship Nauticon: A Digital Exhibition from the Nantucket Historical Association This journal of a whaling voyage was kept by the captain's wife, Susan C. Austin Veeder, 1848-1853.

- Whaling in Alaska and the Yukon (Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean, mostlylate 19th early 20th centuries)

- New York Times article 1891 working on shares, depletion of whales

- "Into the Deep: America, Whaling & the World", PBS, American Experience, 2010.