Painted turtle: Difference between revisions

→Conservation: this caption will fit in better with storyline I'm developing... |

Matt Keevil (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

Although the [[subspecies]] may mix, especially at range boundaries;<ref name="AL intergrade">{{cite web|last=Lee-Sasser|first=Marisa|title=Painted Turtle in Alabama|url=http://www.outdooralabama.com/watchable-wildlife/what/Reptiles/Turtles/pt.cfm|publisher=Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources|accessdate=8 December 2010|month=December|year=2007|quote=Intergrades exhibit a mix of characteristics where their ranges overlap.}}</ref>within the heart of their ranges, they look different. |

Although the [[subspecies]] may mix, especially at range boundaries;<ref name="AL intergrade">{{cite web|last=Lee-Sasser|first=Marisa|title=Painted Turtle in Alabama|url=http://www.outdooralabama.com/watchable-wildlife/what/Reptiles/Turtles/pt.cfm|publisher=Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources|accessdate=8 December 2010|month=December|year=2007|quote=Intergrades exhibit a mix of characteristics where their ranges overlap.}}</ref>within the heart of their ranges, they look different. |

||

* The male eastern painted turtle (''C. p. picta'') is 13–17 cm (5–6 in) long, while the female is 14–17 cm (6–7 in). The |

* The male eastern painted turtle (''C. p. picta'') is 13–17 cm (5–6 in) long, while the female is 14–17 cm (6–7 in). The upper shell ([[carapace]]) is olive green to black and may posses a pale stripe down the middle and a red marking on the margins. The [[scute|scutes]] on the carapace have pale edges at their front edges and occur in straight rows across the back, unlike all other North American turtles including the other three subspecies of Painted Turtle, which have alternating scutes.<ref name='Senneke2003'/> The bottom shell ([[plastron]]) is plain yellow or lightly spotted.<ref name='Nova Scotia Museum'>{{cite web | url = http://museum.gov.ns.ca/amphibians/en/turtles/painted.asp | title = Eastern Painted Turtle Chrysemys picta picta (Schneider) | accessdate = 2010-09-29 | year = 2007 | publisher = Nova Scotia Museum}}</ref> |

||

* The midland painted turtle (''C. p. marginata'') is 10–25 cm (4–10 in) long.<ref name='Natural Resources Canada'>{{cite web | url = http://cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/subsite/glfc-amphibians/chrysemys-picta-marginata | title = Midland Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta marginata) | accessdate = 2010-09-29 | date = 2007-09-24 | publisher = Natural Resources Canada}}</ref> Its top shell has darker coloration around the edges and less of a top stripe than the eastern painted turtle. Its bottom shell contains a dark area in the middle which varies in shade.<ref name=ernst187>{{Harnvb|Ernst|2009|p=187}}</ref> |

* The midland painted turtle (''C. p. marginata'') is 10–25 cm (4–10 in) long.<ref name='Natural Resources Canada'>{{cite web | url = http://cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/subsite/glfc-amphibians/chrysemys-picta-marginata | title = Midland Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta marginata) | accessdate = 2010-09-29 | date = 2007-09-24 | publisher = Natural Resources Canada}}</ref> Its top shell has darker coloration around the edges and less of a top stripe than the eastern painted turtle. Its bottom shell contains a dark area in the middle which varies in shade.<ref name=ernst187>{{Harnvb|Ernst|2009|p=187}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 03:03, 11 December 2010

| Painted Turtle | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Painted turtle | |||

| Scientific classification | |||

| Kingdom: | |||

| Phylum: | |||

| Class: | |||

| Order: | |||

| Family: | |||

| Subfamily: | |||

| Genus: | Chrysemys Gray, 1844

| ||

| Species: | C. picta

| ||

| Binomial name | |||

| Chrysemys picta (Schneider, 1783)

| |||

| Subspecies | |||

|

C. p. bellii | |||

| Synonyms | |||

| |||

The painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) is the only species of Chrysemys, a genus of Emydidae: a family of freshwater turtles. It lives in slow-moving waters, from southern Canada to Louisiana and northern Mexico, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Fossils show that the painted turtle existed 15 million years ago, but four regionally based subspecies (the eastern, midland, southern and western) evolved around the last Ice Age. Human conversion of wetlands is the major threat to the painted turtle, yet its ability to change waterways, sometimes in dramatic groups of hundreds, has helped it remain the most numerous turtle of North America.

The painted turtle is 10–26 cm (4–10 in) long and weighs 300–500 g (11–18 oz); females are larger than males. Its shell is smooth, oval, and flat-bottomed. Its skin is olive to black with distinctive "paintings" of red, orange, or yellow on its head, legs and tail.

Reliant on its surroundings for warmth, the painted turtle is active only during the day, when it can often be seen basking for hours on logs sticking out of the water. In winter, the turtle hibernates, usually in the mud of water bottoms. Summer is the mating season; afterwards, the females dig nests onshore and lay eggs. Hatched turtles grow rapidly until sexual maturity at 2 to 4 years for males and 6 to 10 years for females. Adults in the wild may live for up to 40 years.

The turtle eats aquatic greens, algae, and small water creatures including insects, crustaceans, and fish. The raccoon is its main predator, but it is also preyed upon by snakes, alligators, rodents, and birds of prey.

Taxonomy

The painted turtle (C. picta) is the only species of genus Chrysemys. The genus name comes from Greek for "gold" (chryso) and "freshwater tortoise" (emys), while the species name comes from Latin for "colored" (pictus).[2] The painted turtle was originally described in 1783 by Johann Gottlob Schneider as Testudo picta.[1] An alternate common name for the painted turtle is skilpot (or skillypot, skillpot, skill pot) from the Dutch for tortoise or sea turtle, schildpad.[3]

Over the years, biologists have debated the taxonomic classification of Chrysemys, Pseudemys (cooters), and Trachemys (sliders). As of 1952, many biologists combined Pseudemys with Chrsemys based on similar appearance.[4] In 1964, based on measurements of skull and feet, the three genera were merged into one, but further measurements made in 1967 contradicted the earlier results. The same year, J. Alan Holman pointed out that, although the three turtles were often found together in nature and had similar mating patterns, they did not crossbreed. In the 1980s, studies of turtles' cell structure, biochemistry, and parasites further indicated that Chrysemys, Pseudemys, and Trachemys should remain separate.[5]

The four subspecies of the painted turtle are eastern (C. p. picta), midland (C.p. marginata), southern (C. p. dorsalis), and western (C. p. bellii).[6] The subspecies likely evolved in response to partial geographic isolation during the last ice age: about 100,000 years ago.[7] At that time, painted turtles were divided into three different populations: eastern painted turtles along the southeastern Atlantic coast; southern painted turtles around the southern Mississippi River; and western painted turtles in the southwestern United States.[8] Because the populations were never completely isolated, wholely different species never evolved. When the glaciars retreated about 11,000 years ago, all three subspecies moved northward. The western and southern subspecies met in Missouri and hybridized to produce the midland painted turtles, which then settled the Tennessee River basin, across the Mississippi.[8]

In 2003, David E. Starkey and coworkers classified the southern painted turtle as a separate species: C. dorsalis, but this is largely unrecognized because successful breeding between all subspecies is documented where they overlap.[9]

Description

The painted turtle's shell is 10–26 cm (4–10 in) long[10] and is oval, smooth, and flat-bottomed.[11][12] The top shell color varies from olive to black so as to blend in with the streambed or lakebottom.[13] The bottom shell or belly is yellow with black or red-brown markings in the middle.

The turtle's skin is also olive to black. The neck, legs, and tail have red and yellow stripes. The face has only yellow stripes.[10][12] Behind each eye is a large, yellow spot and streak. The chin has two wide yellow stripes that meet at the tip of the jaw.[13]

The upper jaw is an inverted "V", with a downward-facing, tooth-like projection on each side.[14] The painted turtle's DNA is arranged in 50 chromosomes.[12]

Compared to the adult, the hatchling has a proportionally smaller head, eyes, and tail, and is more vibrantly colored.[15] Its shell is also more circular.[16] Compared to the male, the female painted turtle is larger overall, but with a shorter, thinner tail, and shorter foreclaws.[10][11][12] Females weigh 500 g (18 oz), while males weigh 300 g (11 oz).[17]

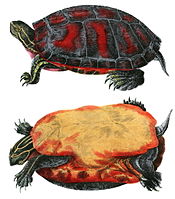

Although the subspecies may mix, especially at range boundaries;[18]within the heart of their ranges, they look different.

- The male eastern painted turtle (C. p. picta) is 13–17 cm (5–6 in) long, while the female is 14–17 cm (6–7 in). The upper shell (carapace) is olive green to black and may posses a pale stripe down the middle and a red marking on the margins. The scutes on the carapace have pale edges at their front edges and occur in straight rows across the back, unlike all other North American turtles including the other three subspecies of Painted Turtle, which have alternating scutes.[19] The bottom shell (plastron) is plain yellow or lightly spotted.[20]

- The midland painted turtle (C. p. marginata) is 10–25 cm (4–10 in) long.[21] Its top shell has darker coloration around the edges and less of a top stripe than the eastern painted turtle. Its bottom shell contains a dark area in the middle which varies in shade.[8]

- The southern painted turtle (C. p. dorsalis), the smallest subspecies, is 10–14 cm (4–5.5 in).[22] Its top stripe is a prominent red[19] and its bottom shell is tan and spotless or nearly so.[23]

- The western painted turtle (C. p. bellii), the largest subspecies, is up to 25 cm (10 in) long.[24] Its top shell has a mesh pattern of light lines.[7] The top stripe is missing or faint. Its bottom shell is covered in a dark coloration which spreads all the way to the edges (further than the midland).[7]

Distribution

Current range

The painted turtle is the only North American turtle whose range stretches from the Atlantic to the Pacific. On the East Coast, it lives from Canadian Maratimes to Georgia. On the West Coast, it lives in British Columbia and Washington, with the range touching the Pacific near the US-Canadian border[7] and offshore on southeast Vancouver Island.[25][nb 1] The most northerly American turtle,[25] its range includes most of southern Canada. To the south, its range reaches the US Gulf Coast in Lousiana. In the US Southwest and northern Mexico, there are only dispersed populations. It is not present at all in Florida.[7]

- The eastern painted turtle ranges from southeastern Canada (Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, but not Prince Edward Island) to Georgia. The western extent of its range is approximately the Appalachians.

- The midland painted turtle ranges from southern Ontario and Quebec, through the eastern US Midwest states to Tennessee and Alabama. It also is found eastward through Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, North and South Carolina, Maryland, and into New England, where it may overlap the eastern painted turtle's range.[10][23]

- The southern painted turtle ranges from southern Illinois, roughly along the Mississipi River, to the Gulf Coast.[23]

- The western painted turtle ranges from Ontario and British Columbia to the central and western United States. Its western boundary reaches the Pacific in the Seattle-Vancouver area. It is also found scattered throughout the southwestern United States and in the northern Mexico state of Chihuahua.[7]

Habitat

To thrive, painted turtles need fresh waters with soft bottoms, basking sites, and aquatic vegetation. They finds their homes in shallow waters with slow moving currents such as creeks, marches, ponds, and the shores of lakes. Along the Atlantic, painted turtles have been seen in brackish waters.[26] The four subspecies have evolved different preferences:

- The eastern painted turtle is more aquatic, only leaving the immediate vicinity of its water body when forced to migrate by drought.[27]

- The midland and southern painted turtles seek especially quiet waters, usually shores and coves. They favor shallows that contain dense vegetation, and have an unusual toleration of pollution.[22][28]

- The western painted turtle may live in streams and lakes, similar to the other painted turtles, but also inhabits pasture ponds and roadside pools. It can be found as high as 1,800 m (5,900 ft).[24]

Population features

Within most of its range, the painted turtle is the most abundant turtle species. Population density ranges from 10–840 individuals per hectare (2.5 acres) of water surface. Warmth drives higher density both long-term (climate or lattitude) and short term (warm spells). Habitat desirability also influences density. Rivers and large lakes have lower densities because only the shore is desirable habitat; the central, deep waters skew the surface-based estimates. Also, lake and river turtles have to make longer linear trips to access equivalent amounts of foraging space.[29]

Adults outnumber juveniles in most populations, but gauging the ratios is tricky because juveniles are harder to catch. With current sampling methods, estimates of age distribution vary widely.[30] Annual mortality of painted turtles drops as they age. The probability of a painted turtle surviving from the egg to its first birthday is just 19%. For females, annual survival rate rises to 45% for juvenils and then to 95% for adults. Male survival rates are lower than females, creating an average male age lower than that of the female.[31] Natural disasters can confound age distributions. For instance, a hurricane can destroy many nests in a region, resulting in less hatchlings the next year.[31] Age distributions may also be skewed by migrations of adults.[30]

Adult sex ratios of painted turtle populations average around 1:1, although with frequent departures from equality.[32] Many populations are slightly male-heavy. However, a few populations are strongly female-imbalenced. One population in Ontario has a female to male ratio of 4:1.[33] Hatchling sex ratio varies based on egg temperature. During the middle third of incubation, temperatures between 23 and 27 °C (73 and 81 °F) produce males, and anything above or below that, females.[34] It does not appear that the female chooses nesting sites to influence sex of the hatchlings,[15] and, within a population, nests will vary sufficiently to give male or female-heavy broods.[30]

| Age | Approximate years BP | Location(s) found (alphabetical) |

|---|---|---|

| Barstovian | 16,300,000 to 13,600,000 | Nebraska |

| Clarendonian | 13,600,000 to 10,300,000 | Kansas |

| Hemphillian | 10,300,000 to 4,900,000 | Nebraska |

| Blancan | 4,750,000 to 1,808,000 | Kansas, Nebraska, and Texas |

| Irvingtonian | 1,800,000 to 300,000 | Kansas, Maryland, Nebraska, and Oklahoma |

| Rancholabrean | 300,000 to 11,000 | Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Nebraska, Nova Scotia, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Virginia |

Fossils

The painted turtle is common in the fossil record. The oldest samples, found in Nebraska, date to about 15 million years ago. Fossils from 15 million to about 5 million years ago are restricted to the Nebraska-Kansas area, but more recent fossils are gradually more widely distributed. Fossils newer than 300,000 years old are present in most of the current range.[35]

Behavior

Daily routine and basking

A cold-blooded reptile, the turtle regulates its temperature by changing its environment, notably basking. All ages of painted turtle bask for warmth, often alongside other species of turtle. Sometimes 50 or more individuals can be seen on one log at a time.[36] Turtles bask on a variety of objects, often partially submerged logs, but have even been seen basking on top of common loons that were covering eggs.[37]

To be active, the turtle maintains an internal body temperature between 17–23 °C (63–73 °F). When fighting infection, it will manipulate its temperature to be 4–5 °C (8–9 °F) higher than normal.[36]

The turtle starts its day at sunrise, emerging from the water to bask for several hours. Warmed for activity, it returns to the water to forage.[38] After becoming chilled, the turtle re-emerges for one to two more cycles of basking and feeding.[39] At night, the turtle drops to the bottom of its water body, or perches on an underwater object, and sleeps.[38]

Seasonal routine and hibernation

In the spring, when the water reaches 15 to 18 °C (59 to 64 °F), the turtle becomes active and feeds for the season. However, when the water temperature exceeds 30 °C (86 °F) the individuals will not forage. In fall, eating ceases at the same range it began in the spring.[40]

In winter, the turtle hibernates. In the north, the inactive season may be as long as October to March, while the most southerly populations may not hibernate at all.[27] During hibernation, the body temperature of the painted turtle averages 6 °C (43 °F).[41] Periods of warm weather bring the turtle out of hibernation and, even in the north, individuals have been seen basking in February.[42]

The painted turtle hibernates by burying itself, either on the bottom of a body of water, close to water in the shore-bank or the burrow of a muskrat, or fully offshore in woods or pastures. When hibernating underwater, the turtle prefers shallow depths, no more than 2 m (6 ft 7 in). Within the mud, it may dig down an additional meter.[41]

Movement

Searching for water, food, or mates, the painted turtle travels up to several kilometers in a single trip.[43] During summer, in response to heat and overgrowth of vegetation, the turtle may vacate shallow marshes for more permanent waters.[43] These short overland migrations may involve hundreds of turtles at once.[27] If heat and drought are prolonged, the turtle will bury itself, and, in extreme cases, die.[44]

Foraging for food drives turtles to cross lakes or travel linearly down creeks. Daily crossings of large ponds have been observed.[44] Capture, tag, and release studies show that sex drives turtle movement. Males travel the most, up to 26 km (16 mi) between captures; females the second most at up to 8 km (5 mi) between captures; and juveniles the least, less than 2 km (1.2 mi) between captures.[43] Males move the most, and are most likely to move between wetlands, because they seek mates.[44]

The painted turtle, through visual recognition, has homing capabilities.[43] Many individuals are able to return to their collection point after being released somewhere else, a trip that may require them to traverse over land. One experiment was done in which 98 specimens were placed varying distances away from their home wetland. Of the original number, 41 returned. When living in a single, large body of water, the painted turtle can home from a maximum of 6 km (4 mi) away. Females may use homing to help locate a proper nesting sight.[43]

Food chain

Diet

All subpecies of painted turtle eat plants and animals, either alive or dead, but with varying tendancies:[40][45]

- The eastern painted turtle's diet is the least studied. It prefers to eat in the water, but has been observed eating on land. The fish it consumes is typically dead or injured.[45]

- The midland painted turtle eats mostly aquatic insects and vascular and non-vascular plants.[46]

- The southern painted turtle's diet changes with age. Adults of this subspecies obtain 88% of their food from plants, juveniles only 13% while the respective percentages of animal food are 10 and 85. This is perhaps due to the fact that the southern painted turtle naturally prefers animal material but, while young turtles are able to obtain it in sufficient quantities (by eating small larvae and such) the adults may not be able to, thus they seek out plant matter (the most abundant food in its habitat).[47] The reversal of feeding habits due to age has also been observed in the false map turtle, which inhabits some of the same range. The most common plants eaten by adults are duckweed and algae. The most common prey are dragonfly larvae and crayfish.[48]

- The western painted turtle's consumption of plants and animals changes seasonally. In early summer, 60% of its diet is insects. In late summer, 55% of its diet is plants.[49] Also of note, white water-lily seeds are consumed by this turtle in high numbers. The hard-coated seeds remain viable as they pass through the turtle's digestive system, which suggests that the turtle is a significant seed disperser.[49]

Hunting behavior

Along the bottom of water bodies, the painted turtle hunts amidst vegetation. The turtle quickly juts its head in and out of aquatic plants to stir potential victims out into the open water, where they are pursued.[40] Large prey is held in the mouth and torn up with the forefeet. The painted turtle also skims the surface of the water with its mouth open to catch fine particulate matter.[40]

Predators

Painted turtles fall prey to many different animals throughout their lives.[29] Eggs are eaten by garter snakes, crows, chipmunks, thirteen-lined ground and gray squirrels, skunks, woodchucks, raccoons, badgers, gray and red fox, and humans.[29] Juveniles fall prey to water bugs, bass, catfish, bullfrogs, snapping turtles, three types of snakes (copperheads and racers and water snakes), herons, rice rats, muskrats, minks and raccoons. Adults are taken by alligators, osprey, red-shouldered hawks, bald eagles and raccoons. Painted turtles defend themselves by kicking, scratching, biting, or urinating.[29] Also, in contrast to land tortoises, painted turtles can turn themselves back over if they are flipped upside down.[50]

Reproduction

Sex

The painted turtle mates from spring to fall in water of 10–28 °C (50–82 °F).[26] Males start making sperm in March (earlier in southern populations) when they can bask to an internal temperature of 17 °C (63 °F).[51][52] The female begins her ovarian cycle in mid-summer and ovulates the following spring.[34]

Courtship begins when a male follows a female until he meets her face to face.[17] He then strokes her face and neck with his front claws, a gesture which a receptive female returns. This process is repeated several times with the male retreating from and then returning to the female until she swims to the bottom, where they copulate.[17][34] As the male is smaller than the female, he is not dominant.[17] The female stores sperm, to be used for up to three clutches in a season, in her oviducts.[53]

Nests

Nesting is done, by the female only, between late May and mid-July.[34] The nests are dug in sandy soil and are vase-shaped and exposed to the south.[54] Nests are often within 200 metres (660 ft) of water, but may be as far away as 600 metres (2,000 ft), with older females nesting further on land. The size of the nest varies depending on the geographic location and size of the female.[54] Females may return to the same nesting site several years in a row, but when several females make their nests close together, the eggs become more vulnerable.[54]

When preparing to dig a nest, the female sometimes presses her throat against the ground of potential sites, perhaps feeling for their moisture, warmth, texture, or smell, although the behavior is as yet unexplained. For the digging, she uses only her back legs. She may begin by excavating several false nests,[54] a behavior also exhibited by wood turtles.[55] The female accumulates so much sand and mud on her hind feet while digging that her mobility can be reduced, making her vulnerable to predators. The female's optimal body temperature during nest construction is 29 to 30 °C (84 to 86 °F).[54] The process of digging and preparing the nest may take four hours to complete. Afterwards, there is a 75% chance she stays the first night.[54]

To aid laying her eggs, the female moistens the area with bladder water.[54] If it is too hot or dry, the female can delay her egg laying. The deposited eggs are elliptical, white, flexible and porous.[56] In the wild, eggs incubate for 72–80 days before hatching:[34] artificial conditions produce similar numbers.[57]

The female can lay five clutches per year, but averages two. 30–50 percent of a population's females do not produce any clutches in a given mating season.[54] Bigger females tend to lay bigger eggs and more eggs per clutch.[58]

Clutch sizes of the subspecies vary, although the differences may reflect different environments, rather than different genetics. The two more northerly subpecies have more eggs per clutch, western (11.9) and midland (7.6), than the two more southerly subspecies, southern (4.2) and eastern (4.9).[nb 3] Within subspecies, also, more northerly females lay larger clutches.[54]

Young

In August and September, the young turtle hatches from its shell, using a projection of its jaw (the egg tooth) to break out.[25] Not all offspring leave the nest, though. Hatchlings may overwinter in the nest to emerge the following spring.[34] This is especially common in the north, where, even with shelter from the nest, freezing temperatures kill many hatchlings. While overwintering, the hatchlings arrange themselves symmetrically in the nest and remain responsive to touch.[59]

Immediately after hatching, turtles are dependant on egg yolk material for sustenance.[59] 7–10 days after emerging from the nest, hatchlings begin feeding to support growth. The young turtles grow rapidly, sometimes doubling in the first year, with the fastest rate when smallest. Likely owing to local habitat and diet, growth rates often differ from population to population in the same area. Among the subspecies, the western painted turtles are the fastest growers.[60]

Overall, females grow faster than males, but must be larger to sexually mature.[61] Males reach sexual maturity at 2 to 4 years old, and females at 6 to 10.[52] Growth slows sharply once maturity is reached and may stop completely.[61] Size and age at maturity increases with the latitude.[62] In the wild, painted turtles aged 40 years have been found.[40]

Human interaction

Conservation

Humans are the largest threat to the painted turtle.[29] Mortality can be caused by highway collisions, intentional killing by anglers, unsafe use of pesticides, and improper care while kept as pets.[29] Eggs and young have been sold to pet shops in the lower Mississippi Basin, individuals of all ages have been consumed by humans as food, and eggs have been used as fish bait.[47] Optimum painted turtle habitat is also shrinking yearly, as is the case with most other North American turtle species[31] however, there are few laws protecting the turtle.[63] Certain Pacific Coast populations in British Columbia are considered endangered and other Intermountain-Rocky populations are of "special concern."[64][65]

Despite these problems, the painted turtle is the predominant North American turtle species: spanning most of North America and having high population densities throughout most of its range. High reproduction rates and its ability to survive in habitats effected by humans, such as polluted wetlands and artificially made ponds, have allowed it to achieve and maintain high numbers in the wild.[63]

In California, some painted turtle populations probably resulted from pet releases. There, they are an invasive species that endangers the local western pond turtle, although competition from similarly-released red-eared sliders is the more pressing threat. [66]

Uses

The painted turtle is sometimes eaten but is not highly regarded as food[47][67][68] as even the largest subspecies, the western painted turtle, is too small for convenience and other, larger, turtles are available.[69] Pet-keeping is often allowed, although simultaneously discouraged. Schools frequently dissect painted turtles; specimens often come from the wild, but may be captive-bred.[70]

Capture

In the U.S., the painted turtle is not federally protected. Many states allow open-season taking of painted turtles with a fishing license, but some do protect their turtles. Alabama allows taking, with a creel limit of ten, of all three subspecies (southern, midland, and eastern) found there, for personal use,[71] but also has a special license for commercial turtle catchers, dealers and farmers.[72] Virginia allows taking with a fishing license with a creel limit of five.[73] Michigan allows open-season taking of one per day, for non-commercial use.[74] Pennsylvania allows one capture per day, from water, with a fishing license.[75] Pennsylvania also says that the meat is safe to eat, but advises cutting away fat and internal organs which may concentrate PCBs.[76] New Hampshire confines taking to the summer.[77] Arizona allows taking four per year with a hunting license.[78] Oregon, where its western painted turtle populations are under pressure, forbids taking of any kind.[79] Missouri forbids the taking of either subspecies (western or southern) present there.[80]

Capturing methods are also regulated by locality. Traps are most common although set lines are also used, as are nets and hand capture. Traps must generally be floating or partially submerged so captured turtles can breathe; trap size, number, construction, and labeling may also be regulated. Several states describe a practice of wanton shooting of turtles "for fun" and prohibit it, or prohibit even deliberate taking with firearms. Use of chemicals or explosives is also generally disallowed. Because other, less numerous, turtle species may be more heavily protected, methods of collection are restricted to allow the release of protected species.[71][73][74][75][77] [78]

Admiration

Native American tribes noticed the painted turtle—young braves were trained to recognize its splashing into water as an alarm—[81]and incorporated it in folklore. A Potawatomi myth describes how the talking turtles, "Painted Turtle" along with allies "Snapping Turtle" and "Box Turtle", outwit the village squaws. Painted Turtle is the star of the conflict and uses his distinctive markings to trick a woman into holding him so he can bite her.[82] An Illini myth recounts how Painted Turtle put his paint on to seduce a chief's daughter into the water.[83]

The painted turtle is the official reptile of four U.S. states:[nb 4] Colorado (western subspecies),[84] Illinois,[85] Michigan,[86] and Vermont.[87]

In addition to the California camp for ill children founded by Paul Newman, some other business names are inspired by the species. Wayne State University Press operates an imprint "named after the Michigan state reptile" that "publishes books on regional topics of cultural and historical interest".[88] Painted Turtle Winery of British Columbia trades on the "laid back and casual lifestyle" of the turtle with a "job description to bask in the sun".[89] Also, there is a guesthouse in British Columbia[90] and a cafe in Maine.[91]

References

- Notes

- ^ Vancouver painted turtle populations may have resulted from escaped pets.[25]

- ^ Painted turtle fossils, of many different ages, have been found all over its current range.[13]

- ^ The differences seen here are thought to be related more to environmental adaptation rather than taxonomic differences.[58]

- ^ Canadian provinces do not have official reptiles.

- Footnotes

- ^ a b "Taxonomic Information". Western Connecticut State University. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ Mitchell, J. C. (1994). The Reptiles of Virginia. Smithsonian Institution Press. As sited in VA Fish and Game Service BOVA Booklet, taxonomy chapter. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ^ Hoffman, Richard L. (1978). "'Skilpot': a request for information" (PDF). Virginia Herpetological Society Bulletin. 85. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

When I was a child living in Clifton Forge, VA, the name by which I learned Chrysemys picta, painted turtle, was 'skilpot'.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Carr 1952, p. 213 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Ernst/Barbour 1989, p. 203

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 214 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b c d e f Ernst 2009, p. 185

- ^ a b c Ernst 2009, p. 187

- ^ Fritz 2007, p. 177

- ^ a b c d "Species Identification". Western Connecticut State University. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ a b "Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta)". Savannah River Ecology Laboratory. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ a b c d Ernst 1994, p. 276

- ^ a b c Ernst 2009, p. 184

- ^ Ernst 1994, p. 277

- ^ a b Ernst 1994, p. 291

- ^ Ernst 1972, p. 143

- ^ a b c d "Painted Turtle Research in Algonquin Provincial Park". The Friends of Algonquin Park. 2005. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ^ Lee-Sasser, Marisa (2007). "Painted Turtle in Alabama". Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

Intergrades exhibit a mix of characteristics where their ranges overlap.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Senneke, Darrell (2003). "Differentiating Painted Turtles (Chrysemys picta ssp)". World Chelonian Trust. Retrieved 2010-12-09.

- ^ "Eastern Painted Turtle Chrysemys picta picta (Schneider)". Nova Scotia Museum. 2007. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ "Midland Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta marginata)". Natural Resources Canada. 2007-09-24. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ a b Carr 1952, p. 226 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b c Ernst 2009, p. 186

- ^ a b Carr 1952, p. 221 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b c d Blood, Donald A. (1998). "Painted Turtle" (brochure). Wildlife Branch, Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, British Columbia. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Ernst/Barbour 1989, p. 202

- ^ a b c Carr 1952, p. 217 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 231 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b c d e f Ernst 1994, p. 294

- ^ a b c Ernst 1994, p. 295

- ^ a b c Ernst 2009, p. 211

- ^ Ernst 1994, p. 294-295

- ^ "Painted Turtle Research in Algonquin Provincial Park". The Friends of Algonquin Park. 2004–2005. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b c d e f "Reproduction". Western Connecticut State University. Retrieved 2010-09-18. Cite error: The named reference "wcsu.edu reproduction" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Ernst 2009, p. 184-185

- ^ a b Ernst 1994, p. 283

- ^ Gervais, Jennifer (2009). "Conservation Assessment For The Western Painted Turtle in Oregon: (Chrysemys picta bellii) Version 1.1" (technical report). U.S.D.A. Forest Service. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Ernst 1994, p. 282

- ^ Ernst 1994, p. 282-283

- ^ a b c d e Ernst 2009, p. 293 Cite error: The named reference "ernst293" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Ernst 1994, p. 284

- ^ Ernst 1994, p. 281

- ^ a b c d e Ernst 1994, p. 286

- ^ a b c Ernst 2009, p. 195

- ^ a b Carr 1952, p. 218 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 232-233 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b c Carr 1952, p. 228 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 227-228 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b Carr 1952, p. 223 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Chaney, Rob (01 July 2010). "Painted native: Turtles indigenous to western Montana have vivid designs, secrets". Missoulian. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ernst 1994, p. 289

- ^ a b Ernst 1994, p. 287

- ^ Ernst 2009, p. 200

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ernst 2009, p. 201

- ^ Ernst 1994, p. 259

- ^ Ernst 2009, p. 203

- ^ Ernst 1994, p. 290

- ^ a b Ernst 2009, p. 202

- ^ a b Ernst 2009, p. 206

- ^ Ernst 2009, p. 207

- ^ a b Ernst 1994, p. 292

- ^ Ernst 2009, p. 197

- ^ a b "Species Identification". Western Connecticut State University. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ "Species Profile Western Painted Turtle Intermountain – Rocky Mountain population". Species at Risk Public Registry. Government of Canada. 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2010-11-12.

- ^ "Species Profile Western Painted Turtle Pacific Coast population". Species at Risk Public Registry. Government of Canada. 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2010-11-12.

- ^ Spinks, Phillip Q. (2003). "Survival of the western pond turtle (Emys marmorata) in an urban California environment" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 113: 257–267. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Carr 1952, p. 218-219 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 233 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 224 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Pike, Sue (21 July 2010). "Painted turtles often used for classroom dissection". Seacoast Media (Dow Jones wire service). Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Nongame Species Protected by Alabama Regulations". Alabama Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "Resident License Information and Applications Packets". Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Nongame Fish, Reptile, Amphibian and Aquatic Invertebrate Regulations". Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Regulations on the Take of Reptiles and Amphibians" (PDF). Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Summary of Pennsylvania Fishing Laws and Regulations - Reptiles and Amphibians - Seasons and Limits". Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "Fish Consumption Advisory" (PDF). Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Rules and Regulations for Reptiles and Amphibians in New Hampshire". New Hampshire Fish and Game Department. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Arizona Reptile and Amphibian Regulations" (PDF). Arizona Game and Fish Department. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "Holding, Propogating, Protected Wildlife" (PDF). Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "MDC Discover Nature Turtles". Missouri Department of Conservation.

Missouri has 17 kinds of turtles; all but three are protected...common snapping turtles and two softshells...

- ^ Macfarlan, Allan and Paulette. Handbook of American Indian Games, Dover Publications, 1985 (orig. 1958).

- ^ Milwaukee Public Museum. Indian Country: Potawatomi Oral Tradition Retrieved 06 December 2010. (Adapted from Alanson Skinner, “The Mascoutens or Prairie Potawatomi Indians, Part III, Mythology and Folklore,” Milwaukee Public Museum Bulletin 6[3]:327–411.)

- ^ Illinois State Museum. The Painted Turtle. Retrieved 6 December 2010. "As told by an unidentified Peoria informant to Truman Michelson, 1916; after Knoepfle 1993."

- ^ Colorado state official press release, 2008

- ^ Illinois state offical website. "Illinois citizens voted to select the painted turtle as the state reptile in 2004. The vote was made official by the General Assembly in 2005."

- ^ Michigan state offical website. "In 1995, the PAINTED TURTLE Chysemys picta) was chosen as the state reptile after a group of Niles fifth graders discovered that Michigan did not have a state reptile."

- ^ 1994 Vermont state resolution. Note that as of 2010, the state webpage did not list an official state reptile, although a nonexhaustive search failed to find a revocation. In any case, it was at least temporarily the Vermont state reptile.

- ^ "Painted Turtle publishing imprint website". Wayne State University Press. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ "Painted Turtle Winery". Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ "Painted Turtle guesthouse website". Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ^ staff reports (12 March 2010). "Eat & Run". The Portland Press Herald. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- Bibliography

- Carr, Archie (1952). "Genus Chrysemys: The Painted Turtles". Handbook of Turtles: The Turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California. Binghamton, New York: Comstock Publishing Associates a Division of Cornell University Press. pp. 213–234.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|work=ignored (help) - Ernst, Carl H.; Barbour, Roger William (1972). "Chrysemys Picta". Turtles of the United States. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 138–146. ISBN 0-8131-1272-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Ernst, Carl H.; Barbour, Roger William (1989). "Chrysemys". Turtles of the World. Washington, D.C., and London: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 201–203. ISBN 0-87474-414-8.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Ernst, Carl H.; Barbour, Roger William; Lovich, Jeffery E. (1994). Turtles of the United States and Canada. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 279–296. ISBN 1-56098-346-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Ernst, Carl H.; Lovich, Jeffery E. (2009). Turtles of the United States and Canada (2 ed.). JHU Press. pp. 185–259. ISBN 9780801891212.

- Fritz, Uwe (2007). "Verterbrate Zoology" (PDF). Checklist of Chelonians of the World. 57 (2): 149–368. Retrieved 2010-12-06.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- Missouri Department of Conservation video of Southern Painted Turtle (click video link): Note the discussion of red line on top of shell.