Amundsen's South Pole expedition: Difference between revisions

→Careful planning and appropriate use of resources: Fixed typos, improved syntax |

→Financing and equipment: Fixed typos |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

The finances for the expedition came from a variety of sources. Many private companies donated goods and the Norwegian Navy provided equipment.<ref>Amundsen, S. 54–56.</ref> A further 20,000 Norwegian crowns were donated by the King and Queen of Norway. Private investors also donated money, the most prominent of which was [[Don Pedro Christophersen]]. On the 9 February 1909 the [[Storting]] — the Norwegian parliament — decided to provide Amundsen and the Fram expedition with a total of 75,000 Norwegian crowns for the necessary repairs and improvements.<ref>[http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext03/tsp1210h.htm Amundsen] in: Project Gutenberg; read the 24th July 2008.</ref> |

The finances for the expedition came from a variety of sources. Many private companies donated goods and the Norwegian Navy provided equipment.<ref>Amundsen, S. 54–56.</ref> A further 20,000 Norwegian crowns were donated by the King and Queen of Norway. Private investors also donated money, the most prominent of which was [[Don Pedro Christophersen]]. On the 9 February 1909 the [[Storting]] — the Norwegian parliament — decided to provide Amundsen and the Fram expedition with a total of 75,000 Norwegian crowns for the necessary repairs and improvements.<ref>[http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext03/tsp1210h.htm Amundsen] in: Project Gutenberg; read the 24th July 2008.</ref> |

||

But after the announcement of Cook and |

But after the announcement of Cook's and Peary's plans to reach the North Pole the sources of money dried up. The Storting now refused additional funding by another badly needed 25,000 crowns. Amundsen faced a deficit of about 150,000 crowns. However, he deliberately did not bother to fully balance his expeditionary budget. He knew that when he reached the South Pole, all would be forgiven. Instead he took out loans where he could. For example, he took out a [[mortgage]] on his own house for over 25,000 crowns.<ref>Huntford, S. 218–219.</ref> |

||

To obtain a sufficient number of sled dogs, Amundsen traveled to [[Copenhagen]]. There he bought one hundred [[Greenland dog]]s from the Royal Greenland Trading Company<ref>The ''Kongelige Grønlandske Handel'' had obtained a monopoly on trade with Greenland in 1776, and held this privilege until 1950.</ref> to be delivered to Denmark in July 1910. Amundsen was convinced that dogs were superior to ponies, the main means of transport used by his competitor Robert Scott.<ref>Amundsen, S. 56–59.</ref> |

To obtain a sufficient number of sled dogs, Amundsen traveled to [[Copenhagen]]. There he bought one hundred [[Greenland dog]]s from the Royal Greenland Trading Company<ref>The ''Kongelige Grønlandske Handel'' had obtained a monopoly on trade with Greenland in 1776, and held this privilege until 1950.</ref> to be delivered to Denmark in July 1910. Amundsen was convinced that dogs were superior to ponies, the main means of transport used by his competitor Robert Scott.<ref>Amundsen, S. 56–59.</ref> |

||

The prefabricated hut, which was 7.8 meters long and 3.9 meters wide, was erected for testing on Amundsen's own property in Norway. The building was then disassembled and repacked — piece by piece — to make the hut ready for transport to Antarctica. The small house had two rooms, one of which served as a kitchen and one as a dining and living room. In a loft there was storage of supplies. Another crucial piece of equipment, the expeditions skis, were specially made out of [[hickory]], which is elastic and hard. They were 1.8 meters long.<ref name="Huntford220">Huntford, S. 220.</ref> |

The prefabricated hut, which was 7.8 meters long and 3.9 meters wide, was erected for testing on Amundsen's own property in Norway. The building was then disassembled and repacked — piece by piece — to make the hut ready for transport to Antarctica. The small house had two rooms, one of which served as a kitchen and one as a dining and living room. In a loft there was storage of supplies. Another crucial piece of equipment, the expeditions skis, were specially made out of [[hickory]], which is elastic and hard. They were 1.8 meters long.<ref name="Huntford220">Huntford, S. 220.</ref> |

||

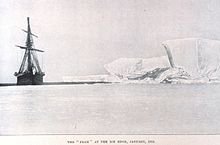

[[Image:Amundsen-Fram.jpg|thumb| |

[[Image:Amundsen-Fram.jpg|thumb|Amundsen's ship ''[[Fram]]'' in pack ice.]] |

||

=== Fram === |

=== Fram === |

||

Revision as of 14:36, 15 December 2010

Roald Amundsen's South Pole expedition (1910–1912) was a Norwegian expedition to Antarctica aiming to be the first to reach the South Pole. The expedition was a success, with five of the mission (Amundsen, Olav Bjaaland, Helmer Hanssen, Sverre Hassel and Oscar Wisting) arriving at the pole on December 14, 1911, beating Robert Falcon Scott and his ill-fated party by thirty-five days.

Preparations

Origins: a change of plans

After crossing the Northwest Passage, Amundsen planned to go to the North Pole and explore the North Polar Basin. On hearing in 1909 that first Frederick Cook and then Robert Peary claimed the Pole, he changed his plans. Using the ship Fram, earlier used by Fridtjof Nansen, he instead set out for Antarctica in 1910. He states in his book The South Pole that he needed to attain the South Pole to guarantee funding for his proposed North Polar journey. In preparation for the new objective, Amundsen studied all the accounts of the previous expeditions to Antarctica. He combined this with his own experiences, both in the Arctic and the Antarctic, in planning for the southern expedition.

Amundsen told no one of his change of plans except Thorvald Nilsen, commander of Fram and his brother Leon Amundsen. He was concerned that Nansen would rescind use of Fram if he learned of the change. (In fact, Nansen supported Amundsen fully.) The original plan had called for sailing Fram around the Horn to the Bering Strait.

The plan

Amundsen collected and surveyed all the available literature, and in conjunction with his own polar experience, developed a precise plan.

The expedition's main goal was to reach the South Pole; scientific studies played only a supporting role. Nevertheless, Amundsen planned to make as many scientific measurements as possible, particularly meteorological ones.[1] In addition, Fram would conduct extensive oceanographic measurements in the Atlantic, which Amundsen designed together with Bjørn Helland-Hansen. These were used as an excuse to be able to board Fram in Norway, rather than in San Francisco as had been previously announced.[2]

According to Amundsen's plans, Fram was to remain in Norway until mid-August and to have Madeira as the only intermediary stop. From there, they would sail around the Cape of Good Hope and advance though the Ross Sea to the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf, which was known at that time as "the Great Ice Barrier". They planned to arrive at the landing site, the Bay of Whales, by the 15th of January. About ten men planned to stay at the Bay of Whales as a coastal group and build a base, while Fram returned to Buenos Aires to resupply and to make further measurements in the Atlantic. In October, the ship would return to the south to rejoin the coastal group.

Once the cabin was set up and the supplies had been brought to land, the coastal group planned to store food and fuel as far south as possible in depots. By the end of these preparations, it would be winter in the Antarctic, which the men would spend working on their equipment. The expedition planned to start out as soon as possible the following spring to arrive at the South Pole ahead of Scott. Amundsen wanted to go directly south from the Bay of Whales and follow the same meridian whenever possible.[3]

Amundsen selected the Bay of Whales as the winter camp location for several reasons. Firstly, it was further south than any other point reachable by boat, which meant about 10% less distance to travel over land.[4] Secondly, Amundsen would be able to learn the conditions and the surface beforehand from the location. In addition, according to James Clark Ross and Shackleton's previous reports, the Bay of Whales was rich with seals and penguins, so there would be a steady food supply. The bay also provided a good place for meteorological observations, because the surrounding land reduced maritime influence on the astronomical conditions. Finally, the site was easily accessible by boat.

Conventional wisdom at the time assumed that the Ross Ice Shelf was floating on water. When Shackleton had visited the Bay of Whales in 1907, he observed extensive calving in the inner bay, and rejected the location as too unstable for a base camp. Amundsen had read Shackleton's account of his 1903 expedition and had noted that the location and shape of the Bay had changed little from when Ross had discovered it seventy years before, in 1841.[5] He reasoned the ice was stable enough for his purposes, and guessed that the ice shelf in the area was grounded on small islands or skerries. Amundsen would later remark that if Shackleton had arrived a few days later, he might have chosen Bay of Whales himself. The ice shelf on which Amundsen's camp rested did not break away and float out to sea until 89 years later, in 2000.[6] The stability of the ice around the bay is due to the lee conditions created by Roosevelt Island.[4]

Financing and equipment

The finances for the expedition came from a variety of sources. Many private companies donated goods and the Norwegian Navy provided equipment.[7] A further 20,000 Norwegian crowns were donated by the King and Queen of Norway. Private investors also donated money, the most prominent of which was Don Pedro Christophersen. On the 9 February 1909 the Storting — the Norwegian parliament — decided to provide Amundsen and the Fram expedition with a total of 75,000 Norwegian crowns for the necessary repairs and improvements.[8]

But after the announcement of Cook's and Peary's plans to reach the North Pole the sources of money dried up. The Storting now refused additional funding by another badly needed 25,000 crowns. Amundsen faced a deficit of about 150,000 crowns. However, he deliberately did not bother to fully balance his expeditionary budget. He knew that when he reached the South Pole, all would be forgiven. Instead he took out loans where he could. For example, he took out a mortgage on his own house for over 25,000 crowns.[9]

To obtain a sufficient number of sled dogs, Amundsen traveled to Copenhagen. There he bought one hundred Greenland dogs from the Royal Greenland Trading Company[10] to be delivered to Denmark in July 1910. Amundsen was convinced that dogs were superior to ponies, the main means of transport used by his competitor Robert Scott.[11]

The prefabricated hut, which was 7.8 meters long and 3.9 meters wide, was erected for testing on Amundsen's own property in Norway. The building was then disassembled and repacked — piece by piece — to make the hut ready for transport to Antarctica. The small house had two rooms, one of which served as a kitchen and one as a dining and living room. In a loft there was storage of supplies. Another crucial piece of equipment, the expeditions skis, were specially made out of hickory, which is elastic and hard. They were 1.8 meters long.[12]

Fram

Colin Archer built Fram (Norwegian for "Forward") in 1892, designing it to withstand the Arctic pack ice. The three-masted schooner had already been used by Fridtjof Nansen and Otto Sverdrup on their respective Arctic expeditions. Fram measured 39 meters long and 11 meters wide, with a volume of 440 gross and 807 net registered tons.[13]

On 9 March 1909, Amundsen asked the Navy Yard in Horten to repair the ship and replace the steam engine with a 180 horsepower diesel engine. Fram was the first arctic exploration ship with a diesel engine, which proved convenient when maneuvering between the ice. The change to a new engine was also motivated by financial reasons -- the diesel engine was possible for one man to operate.[14]

First season, 1910-11

Fram set sail from Norway on the 9th of August, 1910. Amundsen waited until September, when Fram reached Madeira, to let the rest of his crew know of the changed plan of discovering the South Pole. Every member of the crew agreed to continue. His brother, Leon Amundsen, made the news public on October 2. While in Madeira, Amundsen sent a telegram to Scott, notifying him of the change in destination: "BEG TO INFORM YOU FRAM PROCEEDING ANTARCTIC -- AMUNDSEN".

Arrival at the Bay of Whales

The expedition arrived at the eastern edge of Ross Ice Shelf at the large inlet called the Bay of Whales on January 14, 1911. Amundsen located his base camp there and named it Framheim, literally, "Home of Fram". At Framheim, the team offloaded the remaining equipment and supplies from Fram, killed seals and penguins for food, and assembled a wooden hut that had been originally constructed in Norway for this purpose. Fram then departed, to return the following year.

The Bay of Whales location Amundsen chose was 60 statute miles (96 km) closer to the Pole than Scott's camp at Cape Evans on McMurdo Sound. On the other hand, Scott could follow the previously mapped route up the Beardmore Glacier to the Antarctic Plateau, which had been scouted by Ernest Shackleton in 1908, while Amundsen would have to navigate through unknown territory to the Pole.

The cabin at Framheim was an early example of a pre-fabricated structure, and employed a custom dining table which could retract to the ceiling for cleaning beneath. It measured five by four meters, and the walls were made up of four layers of three-inch wooden boards with cardboard between for insulation. Amundsen and the members of his expedition also constructed a network of workshops and storage rooms, including a steam-bath room, carved out of the ice surrounding the main hut.

Amundsen spurned the traditional white tent, and instead dyed his tent material black. He stated that this was to serve three purposes. First, black would absorb what little solar radiation fell upon the tent, helping to heat the living space within. Second, a black tent would provide the best possible contrast against the endless snow and ice, should a search party need to be sent. Finally, the black provided a rest for the eyes, as it contrasted with the endless white of the polar ice and snow fields. In addition, the square, pyramid-style tent was equipped with a single central pole that was lashed, lengthwise, to one of the sledges during travel, avoiding the need to assemble tent-poles, simplifying the process of raising tents. The tent also featured a sewn-in floor, which was an innovation at the time.

Depot laying and preparations

Amundsen and his men created supply depots at 80°, 81° and 82° South, along a line directly south to the Pole. They began this process on February 10. The depots were to supply part of the food necessary for the trip to the Pole, to take place in the following austral Spring. The depots were carefully marked with flags in order not to be missed on the return journey from the Pole. Each depot contained a note with instructions on how to reach the next one. The depot provisioning trips gave Amundsen some experience of conditions on the Ross Ice Shelf and provided crucial testing of their equipment. The Ross Ice Shelf proved to be an excellent surface for the use of ski and dog sleds, Amundsen's primary source of transportation. When the depots were completed, they contained 2750 kg (6700 pounds) of food for the Pole journey.

Winter

The winter period was spent preparing for the attempt on the Pole the following spring. At Framheim, Amundsen continually upgraded his equipment, since he was dissatisfied with standard polar gear. The team kept themselves busy by improving their equipment, particularly the sledges. The sledges, the same kind and manufacturer that Scott used, weighed 75 kg (165 pounds). During the winter, Olav Bjaaland was able to reduce their weight to 22 kg (48 pounds). The sledges were refined by shaving down portions of their frames and runners, achieving a 60% weight reduction without compromising their overall strength. The tents and footwear were also redesigned. On February 4, 1911, members of Scott's team on Terra Nova paid a visit to the Amundsen camp at Framheim.

The race to the Pole, 1911-12

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

A false start to the Pole

Amundsen made a false start to the Pole on September 8, 1911. The temperatures had risen, giving the impression of an austral-Spring warming. This Pole team consisted of eight people, Olav Bjaaland, Helmer Hanssen, Sverre Hassel, Oscar Wisting, Jørgen Stubberud, Hjalmar Johansen, Kristian Prestrud and Amundsen. Soon after departure, temperatures fell below -51 °C (-60 °F). On September 12, the team decided to reach the depot at 80°, deposit their supplies and turn back to Framheim to await warmer conditions. On September 15, the team reached the depot, from which they hurriedly retreated back to Framheim. Prestrud and Hanssen sustained frost-bitten heels on the return. The last day of the return, by Amundsen's own description, was not organized; all accounts except Amundsen's attribute this to poor leadership. Johansen carried Prestrud through a blizzard for hours. At Framheim, Johansen, who had extensive Arctic and dogsled experience with Nansen, openly suggested that Amundsen had not acted properly and had abandoned Prestrud and himself. Amundsen then reorganized the Pole party by reducing its number. Prestrud, with Johansen and Stubberud, was tasked with the exploration of Edward VII Land. This separated Johansen from the Pole team. Johansen was further humiliated by having the inexperienced Prestrud placed in command of the subsidiary expedition. On their return to Norway, Johansen was prevented from landing with the others. He eventually committed suicide in 1913.

The South Pole journey

The new Pole team consisted of Bjaaland, Hanssen, Hassel, Wisting, and Amundsen. They departed on October 19, 1911. They took four sledges and 52 dogs.

The route was directly south from Framheim across the Ross Ice Shelf. On October 23, they reached the 80°S Depot and on November 3, the 82° Depot. On November 15, they reached latitude 85°S and rested a day. They had arrived at the base of the Trans-Antarctic Mountains. The ascent to the Antarctic Plateau began on the 17th of November. They chose a route along the previously unexplored Axel Heiberg Glacier. It was easier than they had expected, though not a simple climb. The team made a few mistakes in choosing the route. They arrived at the edge of the Polar Plateau on November 21 after a four-day climb. Here, 24 of the dogs were killed, giving the place the name "Butcher Shop". Some of the dogs were fed to the remaining sledge teams,[15] while some provided fresh food for the men themselves, and the rest of the meat was cached for the return journey.

The trek across the Polar Plateau to the Pole began on November 25. After three days of blizzard conditions, the team grew impatient. Blizzards and poor weather made progress slow as they crossed the "Devil's Ballroom", a heavily crevassed area. They reached 87°S on December 4. On December 7, they reached the latitude of Shackleton's furthest south, 88°23'S, 180 km (97 nautical miles) from the South Pole. Amundsen paid special tribute to Shackleton and his expedition at this point, reminding his colleagues that Shackleton, Marshall, Adams, and Wild were the first to traverse the Ross Ice Shelf, the first to penetrate the Antarctic Mountain Range, and the first to set foot upon the Antarctic Plateau (named by him King Edward VII Plateau).

Arrival at the South Pole

On December 14, 1911, the team of five, with 16 dogs, arrived at the Pole (90°00'S). They arrived 35 days before Scott's group. Amundsen named their South Pole camp Polheim, "Home on the Pole", and renamed the polar plateau Kong Haakon VII Vidde, "King Haakon VII Plateau". They left a small tent and a letter stating their accomplishment, in case they did not return safely to Framheim.

The five expedition members returned to Framheim on January 25, 1912 with eleven dogs. On their return, Henrik Lindstrom, the cook, said to Amundsen: "And what about the Pole? Have you been there?" The trip had taken 99 days--one day short of their original plan of 100 days--and the distance they covered was about 3,000 km (1,860 miles).

Return and announcement of success

Amundsen's extensive experience, careful preparation and use of high-quality sled dogs (Greenland dogs) paid off in the end. In contrast to the misfortunes of Scott's team, Amundsen's trek proved rather smooth and uneventful, although Amundsen tended later to make light of difficulties.

Amundsen's success was publicly announced on March 7, 1912, when he arrived at Hobart, Australia. Amundsen recounted his journey in the book The South Pole: An Account of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the "Fram", 1910–1912. That year The Explorers Club in New York elected Amundsen to its highest category of membership, Honorary Member.

Comparison of the Amundsen and Scott expeditions

Amundsen's achievement in reaching the Pole was overshadowed for many years in the English speaking world by Scott's failure and death, viewed as a heroic attempt. More recent biographies of Amundsen and Scott, particularly that by Roland Huntford, have changed the popular view of both men and Scott is now often seen as an incompetent leader and planner. Both views tend to the extreme.

The reasons for Amundsen's success in reaching the Pole and returning from it and Scott's failure in same have always been the subject of discussion and controversy. Unforeseeable weather conditions played a significant role in each expedition's fate. Amundsen's expedition experienced normal Antarctic weather at the time it was travelling, though his men still suffered from frostbite, while Scott was travelling later in the season and also experienced exceptionally severe weather, and his entire party lost their lives on the Ross Ice Shelf while returning from the pole. This deadly weather was exceptionally severe for the time of year: between 1985 and 1999 weather of this severity had only been observed once.[16]

Careful planning and appropriate use of resources

There are a number of reasons why Amundsen was successful. His sole purpose was to reach the pole, and he had a greater knowledge of polar technology, put more work into planning, and paid more attention to detail.[citation needed] Amundsen discovered that the Axel Heiberg Glacier proved to be a shorter, though not smoother, route up to the Polar Plateau than the Beardmore Glacier, which was the route discovered by Shackleton three years previously and was the route used by Scott.

Another factor contributing to Amundsen's success was his use of Greenland dogs for transport since these allowed him to head south some three weeks earlier in the Antarctic summer season than Scott, who had to wait until the temperatures rose enough to employ his less resilient ponies.[17] After reaching the Polar Plateau, over half of the dogs were killed and fed to the remaining dogs, reducing the weight of dog food required for the entire trip.

Amundsen did not experience the leakage or evaporation of fuel that Scott did, due to his practice of soldering the fuel tins until they were to be used. As Amundsen used dog-sleds, his team generated much less body heat and therefore perspiration than the British team did in man-hauling. They needed the insulation of fur clothing, which Arctic experience indicated as best.

Amundsen's Assessment

Amundsen's expedition benefited from better equipment and more appropriate sledge animals, a fundamentally different primary task (Amundsen did no surveying on his route south and is known to have taken only two photographs during that southward journey[citation needed]), an understanding of dogs and their handling, and the effective use of skis. He pioneered an entirely new route to the Pole. As he later wrote:

- "I may say that this is the greatest factor -- the way in which the expedition is equipped -- the way in which every difficulty is foreseen, and precautions taken for meeting or avoiding it. Victory awaits him who has everything in order -- luck, people call it. Defeat is certain for him who has neglected to take the necessary precautions in time; this is called bad luck."

- --from The South Pole, by Roald Amundsen.

Legacy

Some of the aircraft navigation waypoints from New Zealand to McMurdo Station in Antarctica are named after 11 of Amundsen’s sledge dogs and Scott’s ponies.[18]

Film Footage

The Norwegian Film Institute and the National Library of Norway hold a collection of original film material documenting Amundsen's historic South Pole Expedition. It includes original sequences filmed between 1910 and 1912 and was inscribed on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register in recognition of its historical value in documenting this important event. [19]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Amundsen, S. 44.

- ^ Huntford, S. 223.

- ^ Amundsen, S. 50–52.

- ^ a b Huntford, S. 216.

- ^ Amundsen, S. 347–379.

- ^ Ranulph Fiennes, Captain Scott (2003) ISBN 0-340-82699-1, account of Robert Falcon Scott's south polar expeditions

- ^ Amundsen, S. 54–56.

- ^ Amundsen in: Project Gutenberg; read the 24th July 2008.

- ^ Huntford, S. 218–219.

- ^ The Kongelige Grønlandske Handel had obtained a monopoly on trade with Greenland in 1776, and held this privilege until 1950.

- ^ Amundsen, S. 56–59.

- ^ Huntford, S. 220.

- ^ Huntford, S. 256; Amundsen, S. 358.

- ^ Huntford, S. 256.

- ^ Roald Amundsen, The South Pole, Volume 2, Chapter XI

- ^ pnas.org - On the role of the weather in the deaths of R. F. Scott and his companions

- ^ Roland Huntford (1999). The Last Place on Earth. Random House. p. p 208. ISBN 0375754741.

{{cite book}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ "Polar Sidekicks Earn a Place on the Map" The New York Times 2010-09-28

- ^ "Roald Amundsen's South Pole Expedition (1910-1912)". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

Sources

- The Last Place on Earth: Scott and Amundsen's Race to the South Pole by Roland Huntford Modern Library (September 7, 1999)

- The South Pole: An Account of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the Fram, 1910 - 1912, by Roald Amundsen, John Murray, 1912.

External links

- Map of Amundsen's and Scott's South Pole journeys at The Fram Museum (Frammuseet)

- The South Pole: An Account of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the Fram at Internet Archive and Google Books (scanned books original editions color illustrated)

- The South Pole: An Account of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the Fram via LibriVox (audiobooks)

- The South Pole: An Account of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the Fram at eBooks @ Adelaide (HTML)