Latin: Difference between revisions

Tag: possible conflict of interest |

|||

| Line 321: | Line 321: | ||

=== Language tools === |

=== Language tools === |

||

* [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/resolveform?lang=la Latin Dictionary Headword Search], at Perseus Hopper, Tufts University. Searches Lewis & Short's ''A Latin Dictionary'' and Lewis's ''An Elementary Latin Dictionary'' |

* [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/resolveform?lang=la Latin Dictionary Headword Search], at Perseus Hopper, Tufts University. Searches Lewis & Short's ''A Latin Dictionary'' and Lewis's ''An Elementary Latin Dictionary'' |

||

* [http://lingua-latina-forum.farvardyn.com/ Lingua Latina Per Se Illustrata] |

* [http://lingua-latina-forum.farvardyn.com/ Lingua Latina Per Se Illustrata Forums] |

||

* [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?lang=la Perseus Word Study Tool], a morphological analysis of inflected Latin words |

* [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?lang=la Perseus Word Study Tool], a morphological analysis of inflected Latin words |

||

* [http://www.u.arizona.edu/~aversa/latin/ Latin Inflector] by Alan Aversa. Analyze inflected words in Latin sentences. |

* [http://www.u.arizona.edu/~aversa/latin/ Latin Inflector] by Alan Aversa. Analyze inflected words in Latin sentences. |

||

Revision as of 07:57, 4 January 2011

| Latin | |

|---|---|

| lingua Latina | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [laˈtiːna] |

| Native to | Roman Republic, Roman Empire, Medieval and Early modern Europe, Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (as lingua franca),

|

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Anciently, Roman schools of grammar and rhetoric.[1] In contemporary time, Opus Fundatum Latinitas.[2] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | la |

| ISO 639-2 | lat |

| ISO 639-3 | lat |

| |

Latin (lingua latīna, IPA: [laˈtiːna]) is an Italic language[3] originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. Although often considered a dead language, a small number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy can speak it fluently, and it continues to be taught in schools and universities.[4] Latin has been, and currently is, used in the process of new word production in modern languages from many different families, including English. Latin and its daughter Romance languages are the only surviving branch of the Italic language family. Other branches, known as Italic languages, are attested in documents surviving from early Italy, but were assimilated during the Roman Republic. The one possible exception is Venetic, the language of the people who settled Venetia, who in Roman times spoke their language in parallel with Latin.

The extensive use of elements from vernacular speech by the earliest authors and inscriptions of the Roman Republic make it clear that the original, unwritten language of the Roman Monarchy was a colloquial form only partly reconstructable called Vulgar Latin. By the late Roman Republic literate persons mainly at Rome had created a standard form from the spoken language of the educated and empowered now called Classical Latin, then called simply Latin or Latinity. The term Vulgar Latin came to mean the various dialects of the citizenry.[5] With the Roman conquest, Latin spread to countries around the Mediterranean, and the vernacular dialects spoken in these areas developed into the Romance languages, including Aragonese, Catalan, Corsican, French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, Sardinian, and Spanish.[6] Classical Latin, however, continued to develop after the fall of the Roman Empire and through the Middle Ages, and was used as the language of international communication, scholarship and science until the 18th century, when it was supplanted by vernacular languages.

Latin is a highly inflected language, with three distinct genders, seven noun cases, four verb conjugations, six tenses, six persons, three moods, two voices, two aspects and two numbers. A dual number is rare and archaic. One of the seven cases is the locative case, generally only used with place nouns. The vocative is nearly identical to the nominative. There are only five fully productive cases; accordingly, different authors list five, six or seven as the number of cases. Adjectives and adverbs are compared, and adjectives are inflected for case, gender, and number. Although Latin has demonstrative pronouns indicating varying degree of closeness, it lacks articles. Later Romance language articles developed from the demonstrative pronouns; e.g., le and la from ille and illa. Romance languages were created by simplification of this inflectional complexity in various ways; e.g., uninflected Italian oggi ("today") from the Latin ablative case, hoc die.

Legacy

The Latin heritage has been delivered in these broad genres:

- Inscriptions

- Latin literature

- Latin words and concepts in modern languages and scientific terminology

- An extensive tradition of instruction in the Latin language, including grammars and dictionaries

Inscriptions

Most inscriptions have been published in an internationally agreed-upon, monumental, multi-volume series termed the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL). Authors and publishers vary but the format is approximately the same: volumes detailing inscriptions with a critical apparatus stating the provenance and relevant information. The reading and interpretation of these inscriptions is the subject matter of the field of epigraphy. There are approximately 180,000 known inscriptions.

Latin literature

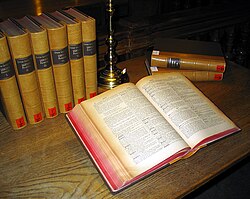

The works of several hundred ancient authors who wrote in Latin have survived in whole or in part, in substantial works or in fragments to be analyzed in philology. They are in part the subject matter of the field of classics. Their works were published in manuscript form before the invention of printing and now exist in carefully annotated printed editions, such as the Loeb Classical Library by Harvard University Press.

Influence on English

In the medieval period, much borrowing from Latin occurred through ecclesiastical usage established by Saint Augustine of Canterbury in the 6th century, or indirectly after the Norman Conquest, through the Anglo-Norman language. From the 16th to the 18th centuries, English writers cobbled together huge numbers of new words from Latin and Greek words. These were dubbed "inkhorn terms", as if they had spilled from a pot of ink. Many of these words were used once by the author and then forgotten, but some were so useful that they survived, such as imbibe and extrapolate. Many of the most common polysyllabic English words also are Latin forms adapted by way of Old French.

Instruction in Latin

Formal support for the study of Latin

The Living Latin movement attempts to teach Latin in the same way that modern living languages are taught, i.e., as a means of both spoken and written communication. Living Latin instruction is provided at the Vatican, and at some institutions in the U.S., such as the University of Kentucky and Iowa State University. A major supplier of Latin textbooks at all levels is Cambridge University Press, which publishes the Cambridge Latin Course series. It includes a subseries of children's texts in Latin by Bell & Forte, using only the Latin language, describing the adventures of a mouse called Minimus.

In the United Kingdom, the Classical Association encourages the study of classics by a variety of methods, such as publications and grants. In the United States and Canada, the American Classical League supports any and every approach to further study of the classics. Its subsidiaries: the National Junior Classical League (with more than 50,000 members) encourages high school students to pursue the study of Latin, and the National Senior Classical League encourages college students to continue their studies of the language. The league also sponsors the National Latin Exam, an educational tool.

Latin is taught as a (mandatory) subject in gymnasium and other "classical" high schools throughout Europe and sometimes beyond. In the United States, although once offered nearly universally, Latin is currently an elective available in some schools, either public or private, at the primary and secondary levels. The ordinary student can no longer count on being able to take Latin, but resources are available to those who seek them. The College Board examinations, an educational tool for the admission of students to colleges, still features one Latin examination on a voluntary basis: Advanced Placement Latin: Vergil.

Latin translations of modern literature

Latin translations of modern literature such as Treasure Island, Robinson Crusoe, Paddington Bear, Winnie the Pooh, Tintin, Asterix, Harry Potter, Walter the Farting Dog, Le Petit Prince, Max und Moritz, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, and The Cat in the Hat and a book of fairy tales, "fabulae mirabiles", are intended to bolster interest in the language. Additional resources include Phrasebooks or resources to render modern terms and concepts into Latin, such as Meissner's Latin Phrasebook.

Synthetic languages based on Latin

Many international auxiliary languages have been heavily influenced by Latin. Interlingua, which lays claim to a sizeable following, is sometimes considered a simplified, modern version of the language. Latino sine Flexione, popular in the early 20th century, is a language created from Latin with its inflections dropped.

History

Latin has been divided into historical phases, each of which is distinguished by minor differences in vocabulary, usage, spelling, morphology and syntax. In addition to the historical phases, Ecclesiastical Latin refers to the styles used by the writers of the Roman Catholic Church as well as Protestant scholars in all historical phases from Late Latin on.

Old, early or archaic Latin

The earliest known is Old Latin, a phase of the early and middle Roman republic attested in inscriptions and the earliest surviving Latin works of literature. During this period, the Latin alphabet was first introduced into the language, and the script evolved from right-to-left or boustrophedon[7] to a left-to-right script.[8] Old Latin is attested in thousands of inscriptions of the Roman Republic and in the writings of older Roman authors, such as Plautus, the first to leave a larger body of literature (several comedies).

Classical Latin

Old Latin was followed in the late republic and empire by Classical Latin, a conscious creation of the orators, poets, historians and other literate men, who wrote the great works of classical literature which were taught in the schools of grammar and rhetoric. The concepts of today's instructional grammars originated in these schools, which served as a sort of informal language academy to maintain and perpetuate the classical language.[9][10]

Vulgar Latin

Philological analysis of Old Latin works, such as the plays of Plautus, which contain dialogue purporting to be the speech of the common people, indicates that contemporaneous with the literary and official language was a spoken language, which has from ancient times been called Vulgar Latin (sermo vulgi in Cicero), the language of the vulgus or "common people." Since the vulgus spoke — but did not write — their language, it can only be known through words and phrases cited by classical authors or in inscriptions.[11]

As vulgar Latin was not under the control or encouragement of the schools of rhetoric, there is no reason to expect any uniformity of speech either diachronically or geographically. Just the opposite must have been true: European populations learning Latin developed their own dialects of the language.[12] This is the situation that prevailed when the Migration Period, ca. 300-700 AD, brought an end to the unity and peace of the Roman world and removed the stabilizing influence of its institutions on the language. A post-classical phase of Latin appeared, Late Latin, in which the spoken forms reappeared, and which is regionalized.

One of the tests as to whether a given Latin feature or usage was in the spoken language is to compare its reflex in a Romance language with the equivalent structure in classical Latin. If it appeared in the Romance language but was not preferred in classical Latin, then it passes the test as being vulgar Latin. For example, grammatical case in nouns is present in classical Latin but not in the Romance languages, excluding Romanian. One might conclude that case endings in regions other than Romania were already wholly or partly missing in the spoken language even while being insisted upon in the written. Also, much of the vocabulary that went into the Romance languages came from Vulgar Latin rather than classical. The following examples follow the formula, classical Latin word/vulgar Latin word/ French word: ignis/focus/feu, equus/caballus/cheval, loquor/parabolare/parler.[13] In each case French does not use the classical Latin word. The words actually used: focus, caballus, etc., must have been in the Vulgar Latin vocabulary.

The expansion of the Roman Empire had spread Latin throughout Europe. Vulgar Latin began to diverge into various dialects and many of these into distinct Romance languages by the 9th century at very latest, when the earliest known writings appeared. These languages must already have been in place. These were, for many centuries, only oral languages, Latin still being used for writing.

Medieval Latin

The term Medieval Latin refers to the written Latin in use during that portion of the post-classical period when no corresponding Latin vernacular existed. The spoken language had developed into the various incipient Romance Languages; however, in the educated and official world Latin continued without its natural spoken base. Moreover, this Latin spread into lands that had never spoken Latin, such as the Germanic and Slavic nations. It became useful as a means of international communication between the member states of the Holy Roman Empire and its allies.

Cut loose from its corrective spoken base and severed from the vanished institutions of the Roman empire that had supported its uniformity, medieval Latin lost the precise knowledge of correctness; for example, suus ("his/her own"), sui ("his/her own") and eius ("his/her") are used almost interchangeably, a confusion not resolved until the Renaissance, in works such as the tract of Lorenzo Valla, De reciprocatione suus et sui. In classical Latin sum and eram are used as auxiliary verbs in the perfect and pluperfect passive, which are compound tenses. Medieval Latin might use fui and fueram instead.[14] Furthermore the meanings of many words have changed and new vocabulary has been introduced from the vernacular.

While these minor changes are not enough to impair comprehension of the language, they introduce a certain flexibility not in it previously. The style of each individual author is characterized by his own uses of classically incorrect Latin to such a degree that one can identify him just by reading his Latin. In that sense medieval Latin is a collection of individual Latins united loosely by the main structures of the language. Some are more classical, others less so.[14] The majority of these writers were influential members of the Christian church: bishops, monks, philosophers, etc.; however, the term "Ecclesiastical Latin" does not accurately apply. There was no uniform language of the church. Late Latin is sometimes classified as medieval, sometimes not. Certainly many of the individual Latins were influenced by the vernaculars of their authors.

Renaissance Latin

The Renaissance briefly reinforced the position of Latin as a spoken language, through its adoption by the Renaissance Humanists. Often led by members of the clergy, they were shocked by the accelerated dismantling of the vestiges of the classical world and the rapid loss of its literature. They strove to preserve what they could. It was they who introduced the practice of producing revised editions of the literary works that remained by comparing surviving manuscripts, and they who attempted to restore Latin to what it had been. They corrected medieval Latin out of existence no later than the 15th century and replaced it with more formally correct versions supported by the scholars of the rising universities, who attempted, through scholarship, to discover what the classical language had been.

Phonology

Pronunciation of Latin by the Romans in ancient times has been reconstructed from a variety of data, such as the evolution of features of the Romance languages, the representation of Latin words in other languages, such as Greek, the metrical patterns of Latin poetry, and more.[15] The table below lists the consonant phonemes of Classical Latin.

Labial Dental Palatal Velar Glottal plain labial Plosive voiced b d ɡ voiceless p t k kʷ aspirated pʰ tʰ kʰ Fricative voiced z voiceless f s h Nasal m n ŋ Rhotic r Approximant l ɫ j w

Latin spelling seems to have been largely phonemic, with each letter corresponding to a specific phoneme in the language, save for some exceptions. In particular, all vowels varied in pronunciation depending upon their vowel length, the letter "n" represented either a dental nasal or a velar nasal, and the letters "i" and "u" represented either consonants or vowels depending on context. Although Classical Latin did not have a distinction between either "i" and "j" or "u" or "v," in later publications, "i" and "u" can represent solely the vowel form while "j" and "v" solely the consonant form.

Most of the letters are pronounced the same as in English, but note the following:

- Consonants:

- c = /k/ (never as in nice)

- g = /ɡ/ (never as in germ)

- j (consonantal i) = /j/ (like English y in you) The "i" is pronounced as a consonant if in the beginning of word before a vowel or between two vowels.

- n = /n/ or /ŋ/ If "n" occurs before "c", "g" or "x" or directly after a "g,"[16] it is pronounced /ŋ/ ("ng" as in "sing"). Otherwise, it is pronounced /n/[17]

- t = /t/ (never as in English nation)

- v (consonantal u) = /enwiki/w/ The "u" is pronounced as a consonant also if beginning a word and before a vowel or if placed between two vowels.

- x = /ks/

- Vowels:

- a = /a/ when short and /aː/ when long.

- e = /ɛ/ (as in pet) when short and /eː/ (somewhat as in English they) when long.

- i = /ɪ/ (as in pin) when short and /iː/ (as in machine) when long

- o = /ɔ/ (as in British English law) when short and /oː/ (somewhat as in holy) when long.

- u = /ʊ/ (as in put) when short and /uː/ (as in true) when long.

A vowel followed by an m or n (later in the life of Latin), either at the end of a word or before another consonant, is nasal, as in monstrum /mõstrũ/.[16]

Orthography

Latin was written using the Latin Alphabet, derived from the Old Italic alphabet, in turn drawn from the Greek and ultimately the Phoenician alphabet.[18] This alphabet has continued to be used throughout centuries as the script for the Romance, Celtic, Germanic, Baltic, Finnic, and some Slavic languages (Croatian and Czech, for example), as well as for others as Indonesian, Vietnamese, and Niger-Congo languages.

The Latin alphabet has varied in number of letters. When it was first adopted from the Etruscan alphabet, it contained only 21.[19] Later, “G”, representing /ɡ/, formerly included under “C”, was innovated to replace “Z”, which was non-functional, as the language had no voiced alveolar fricative at the time.[20] The letters “Y” and “Z” were later added to represent the Greek Upsilon and Zeta respectively in Greek loanwords.[20] “W” was created in the 11th century from VV. It represented /enwiki/w/ in Germanic languages, not in Latin, which still uses “V” for the purpose. “J” was distinguished from the original “I” only during the late Middle Ages along with the letter “U” from “V”.[20] Although some dictionaries use “J” it is for the most part eschewed for Latin text as non-original, although other languages use it.

Classical Latin did not contain punctuation, macrons (although apices were used to distinguish length in vowels), lowercase letters,[21] or interword spacing (but the interpunct was used at times in Latin’s history). So, a sentence originally written as:

- LVGETEOVENERESCVPIDINESQVE

would be rendered in a modern edition as

- Lugete, O Veneres Cupidinesque

or with macrons

- Lūgēte, Ō Venerēs Cupīdinēsque.

and translated as

The Roman cursive script is commonly found on the many wax tablets excavated at sites such as forts, an especially extensive set having been discovered at Vindolanda on Hadrian's Wall in Britain. Curiously enough, most of the Vindolanda tablets show spaces between words, though spaces were avoided in monumental inscriptions from that era.

Grammar

Latin is a synthetic, fusional language: affixes (often suffixes, which usually encode more than one grammatical category) are attached to fixed stems to express gender, number, and case in adjectives, nouns, and pronouns—a process called declension. Affixes are attached to fixed stems of verbs, as well, to denote person, number, tense, voice, mood, and aspect—a process called conjugation.

Nouns

There are seven Latin noun cases. These mark a noun's syntactic role in the sentence, so word order is not as important in Latin as it is in some other languages, such as English. Words can typically be moved around in a sentence without significantly altering its meaning, although the emphasis may have been altered.

- Nominative: used when the noun is the subject or a predicate nominative. The thing or person acting; e.g., the girl ran: puella currit, or currit puella

- Vocative: used when the noun is used in a direct address. The vocative form of a noun is the same as the nominative except for second declension nouns ending in -us. The -us becomes an -e or if it ends in -ius (such as filius) then the ending is just -i (fili) (as distinct from the plural nominative (filii)). (e.g., "Master!" shouted the slave. "Domine!" servus clamavit.)

- Accusative: used when the noun is the direct object of the sentence/phrase, with certain prepositions, or as the subject of an infinitive. The thing or person having something done to them. (e.g., The slave woman carries the wine. Ancilla vinum portat.) In addition, there are certain constructions where the accusative can be used for the subject of a clause, one being the indirect statement.

- Genitive: used when the noun is the possessor of an object (e.g., "the horse of the man", or "the man's horse"—in both of these instances, the word man would be in the genitive case when translated into Latin). Also indicates material of which something greater is made (e.g., "a group of people"; "a number of gifts"—people and gifts would be in the genitive case). Some nouns are genitive with special verbs and adjectives too. (e.g., The cup is full of wine. Poculum plenum vini est. The master of the slave had beaten him. Dominus servi eum verberaverat.)

- Dative: used when the noun is the indirect object of the sentence, with special verbs, with certain prepositions, and if used as agent, reference, or even possessor. (e.g., The merchant hands over the stola to the woman. Mercator feminae stolam tradit.)

- Ablative: used when the noun demonstrates separation or movement from a source, cause, agent, or instrument, or when the noun is used as the object of certain prepositions; adverbial. (e.g., You walked with the boy. tu cum puero ambulavisti.)

- Locative, used to indicate a location and services (corresponding to the English "in" or "at"). This is far less common than the other six cases of Latin nouns and usually applies to cities, small towns, and islands smaller than the island of Rhodes, but not including Rhodes, along with a few common nouns. In the first and second declension singular, its form coincides with the genitive (Roma becomes Romae, "in Rome"). In the plural, and in the other declensions, it coincides with the dative and ablative (Athenae becomes Athenis, "at Athens").

Latin lacks definite and indefinite articles; thus puer currit can mean either "the boy is running" or "a boy is running."

Verbs

Verbs in Latin are usually identified by four main conjugations, groups of verbs with similarly inflected forms. The first conjugation is typified by active infinitive forms ending in -āre, the second by active infinitives ending in -ēre, the third by active infinitives ending in -ere, and the fourth by active infinitives ending in -īre. However, there are exceptions to these rules. Further, there is a subset of the 3rd conjugation, the -iō verbs, which behave somewhat like the 4th conjugation. There are six general tenses in Latin (present, imperfect, future, perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect), three grammatical moods (indicative, imperative and subjunctive, in addition to the infinitive, participle, gerund, gerundive and supine), three persons (first, second, and third), two numbers (singular and plural), two voices (active and passive), and a few aspects. Verbs are described by four principal parts:

- The first principal part is the first person (or third person for impersonal verbs) singular, present tense, indicative mood, active voice form of the verb (or passive voice for verbs lacking an active voice).

- The second principal part is the present infinitive active (or passive for verbs lacking an active) form.

- The third principal part is the first person (or third person for impersonal verbs) singular, perfect indicative active (or passive when there is no active) form.

- The fourth principal part is the supine form, or alternatively, the nominative singular, perfect passive participle form of the verb. The fourth principal part can show either one gender of the participle, or all three genders (-us for masculine, -a for feminine, and -um for neuter). It can also be the future participle when the verb cannot be made passive. Most modern Latin dictionaries, if only showing one gender, tend to show the masculine; however, many older dictionaries will instead show the neuter. The fourth principal part is sometimes omitted for intransitive verbs, although strictly in Latin these can be made passive if used impersonally.

Vocabulary

As Latin is an Italic language, most of its vocabulary is likewise Italic, deriving ultimately from PIE. However, because of close cultural interaction, the Romans not only had adapted the Etruscan alphabet to form the Latin alphabet, but also had borrowed some Etruscan words into their language, including persona (mask) and histrio (actor).[22] Latin also included vocabulary borrowed from Oscan, another Italic language.

After the Fall of Tarentum (272 BC), the Romans began hellenizing, or adopting features of Greek culture, including the borrowing of Greek words, such as camera (vaulted roof), sumbolum (symbol), and balineum (bath).[22] This hellenization led to the addition of “Y” and “Z” to the alphabet to represent these Greek sounds.[23] Subsequently the Romans transplanted Greek art, medicine, science and philosophy to Italy, paying almost any price to entice Greek skilled and educated persons to Rome, and sending their youth to be educated in Greece. Thus, many Latin scientific and philosophical words were Greek loanwords or had their meanings expanded by association with Greek words, as ars (craft) for τέχνη.[24]

Because of the Roman Empire’s expansion and subsequent trade with outlying European tribes, the Romans borrowed some northern and central European words, such as beber (beaver), of Germanic origin, and bracae (breeches), of Celtic origin.[24] The specific dialects of Latin across Latin-speaking regions of the former Roman Empire after its fall were influenced by languages specific to the regions. These spoken Latins evolved into particular Romance languages.

During and after the adoption of Christianity into Roman society, Christian vocabulary became a part of the language, formed either from Greek or Hebrew borrowings, or as Latin neologisms.[25] Continuing into the Middle Ages, Latin incorporated many more words from surrounding languages, including Old English and Germanic languages.

Over the ages Latin-speaking populations produced new adjectives, nouns and verbs by affixing or compounding meaningful segments.[26] For example, the compound adjective, omnipotens, "all-powerful," was produced from the adjectives omnis, "all", and potens, "powerful", by dropping the final s of omnis and concatenating. Often the concatenation changed the part of speech; i.e., nouns were produced from verb segments or verbs from nouns and adjectives.[27]

Modern use

Latin lives in the form of Ecclesiastical Latin used for edicts and papal bulls issued by the Catholic Church, and in the form of a sparse sprinkling of scientific or social articles written in it, as well as in numerous Latin clubs. Latin vocabulary is used in science, academia, and law. Classical Latin is taught in many schools often combined with Greek in the study of Classics, though its role has diminished since the early 20th century. The Latin alphabet, together with its modern variants such as the English, Spanish, French, Portuguese and German alphabets, is the most widely used alphabet in the world. Terminology deriving from Latin words and concepts is widely used, among other fields, in philosophy, medicine, biology, and law, in terms and abbreviations such as subpoena duces tecum, q.i.d. (quater in die: "four times a day"), and inter alia (among other things). These Latin terms are used in isolation, as technical terms. In scientific names for organisms, Latin is typically the language of choice, followed by Greek.

The largest organization that still uses Latin in official and quasi-official contexts is the Roman Catholic Church (particularly in the Latin Rite). The Tridentine Mass uses Latin, although the Mass of Paul VI is usually said in the local vernacular language; however, it can be and often is said in Latin, particularly in the Vatican. Indeed, Latin is still the official standard language of the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church, and the Second Vatican Council merely authorized that the liturgical books be translated and optionally used in the vernacular languages. Latin is the official language of the Holy See and the Vatican City-State. The Vatican City is also home to the only ATM where instructions are given in Latin.[28]

Some films of relevant ancient settings, such as Sebastiane and The Passion of the Christ, have been made with dialogue in Latin for purposes of realism. Occasionally, Latin dialogue is used because of its association with religion or philosophy, in such film/TV series as the Exorcist and Lost (Jughead). Subtitles are usually employed for the benefit of audiences who do not understand Latin. There are also songs written with Latin lyrics.

Many organizations today have Latin mottos, such as "Semper Paratus" (always ready), the motto of the United States Coast Guard, and "Semper Fidelis" (always faithful), the motto of the United States Marine Corps. Several of the states of the United States also have Latin mottos, such as "Montani Semper Liberi" (Mountaineers are always free), the state motto of West Virginia, "Sic semper tyrannis" (Thus always to tyrants), that of Virginia, and "Esse Quam Videri" (To be rather than to seem), that of North Carolina.

Latin grammar has been taught in most Italian schools since the 18th century: for example, in the Liceo classico and Liceo scientifico, Latin is still one of the primary subjects. Latin is taught in many schools and universities around the world as well.

Occasionally, some media outlets broadcast in Latin, which is targeted at the audience of enthusiasts. Notable examples include Radio Bremen in Germany, YLE radio in Finland and Vatican Radio & Television; all of which broadcast news segments and other material in Latin.[29][30]

There are many websites and forums maintained in Latin by enthusiasts. The Latin Wikipedia has over 40,000 articles written in Latin.

See also

- Hybrid word

- Classical compound

- Latin influence in English

- List of Greek words with English derivatives

- List of Latin phrases

- Latin Mnemonics

- Latin school

- List of Latin abbreviations

- List of Latin and Greek words commonly used in systematic names

- List of Latin words with English derivatives

- List of Latinised names

- List of legal Latin terms

- Medical terminology

- Romanization (cultural)

- Toponymy

- Wikipedia:IPA for Latin

- Greek and Latin roots in English

Notes

- ^ "Schools". Britannica (1911 ed.).

- ^ Opus Fundatum Latinitas is an organ of the Roman Catholic Church, and regulates Latin with respect to its status as official language of the Holy See and for use by Catholic clergy.

- ^ Sandys, John Edwin (1910). A companion to Latin studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 811–812.

- ^ Hu, Winnie (October 6, 2008). "A Dead Language That's Very Much Alive". Nytimes.com.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Clark 1900, pp. 1–3

- ^ Bryson, Bill (1996). The mother tongue: English and how it got that way. New York: Avon Books. pp. 33–34.

- ^ Diringer 1947, pp. 533–4

- ^ Sacks, David (2003). Language Visible: Unraveling the Mystery of the Alphabet from A to Z. London: Broadway Books. p. 80.

- ^ Pope, Mildred K. From Latin to modern French with especial consideration of Anglo-Norman; phonology and morphology. Publications of the University of Manchester, no. 229. French series, no. 6. Manchester: Manchester university press. p. 3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Monroe, Paul (1902). Source book of the history of education for the Greek and Roman period. London, New York: Macmillan & Co. pp. 346–352.

- ^ Herman 2000, pp. 17–18

- ^ Herman 2000, p. 8

- ^ Herman 2000, pp. 1–3

- ^ a b Thorley, John (1998). Documents in medieval Latin. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 13–15.

- ^ Allen 2004, pp. viii–ix Foreword to the First Edition.

- ^ a b Lloyd, Paul M. (1987). From Latin to Spanish. Diane Publishing, p.81

- ^ Allen 2004, p. 84

- ^ Diringer 1947, pp. 451, 493, 530

- ^ Diringer 1947, p. 536

- ^ a b c Diringer 1947, p. 538

- ^ Diringer 1947, p. 540

- ^ a b Holmes & Schultz 1938, p. 13

- ^ Sacks, David (2003). Language Visible: Unraveling the Mystery of the Alphabet from A to Z. London: Broadway Books. p. 351.

- ^ a b Holmes & Schultz 1938, p. 14

- ^ Norberg, Dag; Johnson, Rand H, Translator (2004) [1980]. "Manuel pratique de latin médiéval" (Document). University of Michigan.

{{cite document}}:|first2=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|contribution=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jenks 1911, pp. 3, 46

- ^ Jenks 1911, pp. 35, 40

- ^ Moore, Malcom (28 January 2007). "Pope's Latinist pronounces death of a language". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Latein: Nuntii Latini mensis lunii 2010: Lateinischer Monats rückblick" (in Latin). Radio Bremen. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- ^ "Nuntii Latini" (in Latin). YLE Radio 1. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

References

- Allen, William Sidney (2004). Vox Latina — a Guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Latin (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Bennett, Charles E. (1908). Latin Grammar. Chicago: Allyn and Bacon.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Clark, Victor Selden (1900). Studies in the Latin of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Lancaster: The New Era Printing Company.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Diringer, David (1996) [1947]. The Alphabet - A Key to the History of Mankind. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Private Ltd. ISBN 81-215-0748-0.

- Herman, József; Wright, Roger (Translator) (2000). Vulgar Latin. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - Holmes, Urban Tigner; Schultz, Alexander Herman (1938). A History of the French Language. New York: Biblo-Moser. ISBN 0-8196-0191-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Jenks, Paul Rockwell (1911). A Manual of Latin Word Formation for Secondary Schools. New York: D.C. Heath & Co.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Palmer, Frank Robert (1984). Grammar (2nd ed.). Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England; New York, N.Y., U.S.A.: Penguin Books.

- Vincent, N. (1990). "Latin". In Harris, M. (ed.). The Romance Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-520829-3.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|editor1-first=and|editor-first=specified (help); More than one of|editor1-last=and|editor-last=specified (help) - Waquet, Françoise; Howe, John (Translator) (2003). Latin, or the Empire of a Sign: From the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Centuries. Verso. ISBN 1-85984-402-2.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - Wheelock, Frederic (2005). Latin: An Introduction (6th ed.). Collins. ISBN 0-06-078423-7.

External links

Language tools

- Latin Dictionary Headword Search, at Perseus Hopper, Tufts University. Searches Lewis & Short's A Latin Dictionary and Lewis's An Elementary Latin Dictionary

- Lingua Latina Per Se Illustrata Forums

- Perseus Word Study Tool, a morphological analysis of inflected Latin words

- Latin Inflector by Alan Aversa. Analyze inflected words in Latin sentences.

- Online conjugator of Latin verbs, by Verbix

- Online interface to Words by William Whittaker. Accepts English words or Latin phrases

- Template:Dmoz

- Latin Composition Tool by Marq Jefferson. Makes input of macrons much simpler, excellent for Latin scansion exercises and beginning students

- Wiktionary's Latin appendices (has many word lists)

Courses

- Hatfield, Brent (2010). "Learn Latin Online Free". Free online Latin course utilizing youtube videos and downloadable worksheets. Brent Hatfield. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- Cherryh, CJ (1999). "Latin 1:the Easy Way". CJ Cherryh. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Byrne, Carol (1999). "Simplicissimus". The Latin Mass Society of England and Wales. Retrieved 24 June 2010. [dead link]

- Harsch, Ulrich (1996–2010). "Ludus Latinus Cursus linguae latinae". Bibliotheca Augustiana (in Latin). Augsburg: University of Applied Sciences. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link)

Grammar and study

- Bennett, Charles E. (2005) [1908]. New Latin Grammar (2nd ed.). Project Gutenberg.

- Batzarov, Zdravko (2000). "Latin Language (Lingua Latina)". Orbis Latinus. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Lehmann, Winifred P.; Slocum, Jonathan (2008). "Latin Online, Series Introduction". The University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- Wilkinson, Hugh Everard (2010). "The World of Comparative and Historical Linguistics (A Historical Survey of the Romance Languages)". Page ON Park. NTT Comminications. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "LatinHelper: the". Page ON Park. LatinHelper.com. 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

Phonetics

- "Latin Pronunciation - a Beginner's Guide". h2g2, BBC. 2001.

- Cui, Ray (2005). "Phonetica Latinae-How to pronounce Latin". Ray Cui. Retrieved 25 June 2010.