Early human migrations: Difference between revisions

→Exodus from Africa: –space |

Giornorosso (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

'''Early human migrations''' began when ''[[Homo erectus]]'' first migrated out of [[Africa]] over the [[Levantine corridor]] and [[Horn of Africa]] to [[Eurasia]] about 1.8 million years ago, a migration probably sparked by the development of [[language]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Fischer|first=Steven Roger|title=A history of language|publisher=Reaktion Books|year=2004|series=Globalities Series|isbn=186189080X|url=http://books.google.com/?id=5i1Ql7QQy0kC&pg=PA37}}</ref> The expansion of ''H. erectus'' out of Africa was followed by that of ''[[Homo antecessor]]'' into Europe around 800,000 years ago, followed by ''[[Homo heidelbergensis]]'' around 600,000 years ago, where they probably evolved to become the [[Neanderthal]]s.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1016/j.tree.2005.05.019|last=Finlayson|first=Clive|year=2005|title=Biogeography and evolution of the genus Homo|journal=Trends in Ecology & Evolution|publisher=Elsevier|volume=20|issue=8|pages=457–463|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VJ1-4GCXBFD-1&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_searchStrId=1155384170&_rerunOrigin=scholar.google&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=f8d1d91c6d2224388441285a8197a437|pmid=16701417}}</ref> |

'''Early human migrations''' began when ''[[Homo erectus]]'' first migrated out of [[Africa]] over the [[Levantine corridor]] and [[Horn of Africa]] to [[Eurasia]] about 1.8 million years ago, a migration probably sparked by the development of [[language]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Fischer|first=Steven Roger|title=A history of language|publisher=Reaktion Books|year=2004|series=Globalities Series|isbn=186189080X|url=http://books.google.com/?id=5i1Ql7QQy0kC&pg=PA37}}</ref> The expansion of ''H. erectus'' out of Africa was followed by that of ''[[Homo antecessor]]'' into Europe around 800,000 years ago, followed by ''[[Homo heidelbergensis]]'' around 600,000 years ago, where they probably evolved to become the [[Neanderthal]]s.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1016/j.tree.2005.05.019|last=Finlayson|first=Clive|year=2005|title=Biogeography and evolution of the genus Homo|journal=Trends in Ecology & Evolution|publisher=Elsevier|volume=20|issue=8|pages=457–463|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VJ1-4GCXBFD-1&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_searchStrId=1155384170&_rerunOrigin=scholar.google&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=f8d1d91c6d2224388441285a8197a437|pmid=16701417}}</ref> |

||

Modern humans, ''[[Homo sapiens]]'', evolved in Africa up to 200,000 years ago and reached the [[Near East]] around |

Modern humans, ''[[Homo sapiens]]'', evolved in Africa up to 200,000 years ago and reached the [[Near East]] around 125 millennia ago.<ref>http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/69197/title/Hints_of_earlier_human_exit_from_Africa</ref> From the Near East, these populations spread east to [[Paleolithic South Asia|South Asia]] by 50 millennia ago, and on to [[Prehistoric Australia|Australia]] by 40 millennia ago{{citation needed}}, when for the first time ''H. sapiens'' reached territory never reached by ''H. erectus''. [[Paleolithic Europe|Europe]] was reached by ''H. sapiens'' around 40 millennia ago, replacing the Neanderthal population. [[East Asia]] was reached by 30 millennia ago. |

||

The date of [[Models of migration to the New World|migration to North America]] is disputed; it may have taken place around [[28th millennium BC|30 millennia ago]], or considerably later, around [[12th millennium BC|14 millennia ago]]. The [[Austronesian languages#Homeland|Pacific islands of Polynesia]] began to be colonized around 1300 BC, and completely colonized by around 900 AD. The ancestors of Polynesians left Taiwan around 5200 years ago. |

The date of [[Models of migration to the New World|migration to North America]] is disputed; it may have taken place around [[28th millennium BC|30 millennia ago]], or considerably later, around [[12th millennium BC|14 millennia ago]]. The [[Austronesian languages#Homeland|Pacific islands of Polynesia]] began to be colonized around 1300 BC, and completely colonized by around 900 AD. The ancestors of Polynesians left Taiwan around 5200 years ago. |

||

Revision as of 12:58, 28 January 2011

Early human migrations began when Homo erectus first migrated out of Africa over the Levantine corridor and Horn of Africa to Eurasia about 1.8 million years ago, a migration probably sparked by the development of language.[1] The expansion of H. erectus out of Africa was followed by that of Homo antecessor into Europe around 800,000 years ago, followed by Homo heidelbergensis around 600,000 years ago, where they probably evolved to become the Neanderthals.[2]

Modern humans, Homo sapiens, evolved in Africa up to 200,000 years ago and reached the Near East around 125 millennia ago.[3] From the Near East, these populations spread east to South Asia by 50 millennia ago, and on to Australia by 40 millennia ago[citation needed], when for the first time H. sapiens reached territory never reached by H. erectus. Europe was reached by H. sapiens around 40 millennia ago, replacing the Neanderthal population. East Asia was reached by 30 millennia ago.

The date of migration to North America is disputed; it may have taken place around 30 millennia ago, or considerably later, around 14 millennia ago. The Pacific islands of Polynesia began to be colonized around 1300 BC, and completely colonized by around 900 AD. The ancestors of Polynesians left Taiwan around 5200 years ago.

Early humans (before Homo sapiens)

Early members of the Homo genus, i.e. Homo ergaster, Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis, migrated from Africa during the Early Pleistocene, possibly as a result of the operation of the Saharan pump, around 1.9 million years ago, and dispersed throughout most of the Old World, reaching as far as Southeast Asia. The date of original dispersal beyond Africa virtually coincides with the appearance of Homo ergaster in the fossil record, and the associated first emergence of full bipedalism, and about half a million years after the appearance of the Homo genus itself and the first stone tools of the Oldowan industry. Key sites for this early migration out of Africa are Riwat in Pakistan (1.9 Mya), Ubeidiya in the Levant (1.5 Mya) and Dmanisi in the Caucasus (1.7 Mya).

China was populated more than a million years ago,[4] as early as 1.66 Mya based on stone artifacts found in the Nihewan Basin.[5] Stone tools found at Xiaochangliang site were dated to 1.36 million years ago.[6] The archaeological site of Xihoudu (西侯渡) in Shanxi Province is the earliest recorded use of fire by Homo erectus, which is dated 1.27 million years ago.[4]

Southeast Asia (Java) was reached about 1.7 million years ago (Meganthropus). West Europe was first populated around 1.2 million years ago (Atapuerca).[7]

Bruce Bower has suggested that Homo erectus may have built rafts and sailed oceans, a theory that has raised some controversy.[8]

Homo sapiens sapiens migrations

Homo sapiens sapiens is supposed to have appeared in East Africa between 200,000 and 100,000 years ago (Homo sapiens idaltu, found at site Middle Awash in Ethiopia, lived about 160,000 years ago,[9] is considered the oldest known anatomically modern human).

From there they spread around the world. An exodus from Africa over the Arabian Peninsula around 60,000 years ago brought modern humans to Eurasia, with one group rapidly settling coastal areas around the Indian Ocean and one group migrating north to steppes of Central Asia.[10]

The migration path is a matter of debate and study. Genetics have shed some light on this matter.

Within Africa

The matrilinear most recent common ancestor shared by all living human beings, dubbed Mitochondrial Eve, probably lived roughly 120-150 millennia ago, the time of Homo sapiens idaltu, probably in East Africa.[citation needed]

The broad study of African genetic diversity headed by Dr. Sarah Tishkoff found the San people to express the greatest genetic diversity among the 113 distinct populations sampled, making them one of 14 "ancestral population clusters." The research also located the origin of modern human migration in south-western Africa, near the coastal border of Namibia and Angola.[11]

Around 100,000-80,000 years ago, three main lines of Homo sapiens diverged. Bearers of mitochondrial haplogroup L0 (mtDNA) / A (Y-DNA) colonized Southern Africa (the ancestors of the Khoisan (Capoid) peoples), bearers of haplogroup L1 (mtDNA) / B (Y-DNA) settled Central and West Africa (the ancestors of western pygmies), and bearers of haplogroups L2, L3, and others mtDNA remained in East Africa (the ancestors of Niger-Congo and Nilo-Saharan speaking peoples). (see L-mtDNA)

Exodus from Africa

According to the Recent African Origin hypothesis a small group of the L3 bearers living in East Africa migrated north east, possibly searching for food or escaping adverse conditions, crossing the Red Sea about 70 millennia ago, and in the process going on to populate the rest of the world. According to some authors, this happened in several waves close in time. For example, Wells says that the early travelers followed the southern coastline of Asia, crossed about 250 kilometers [155 miles] of sea (probably by simple boats or rafts[12]), and colonized Australia by around 50,000 years ago. The Aborigines of Australia, Wells says, are the descendants of the first wave of migration out of Africa.[13]

Around 50,000 years ago the world was entering the last ice age and water was trapped in the polar ice caps, so sea levels were much lower. Today at the Gate of Grief the Red Sea is about 12 miles (20 kilometres) wide but 50,000 years ago it was much narrower and sea levels were 70 metres lower. Though the straits were never completely closed, there may have been islands in between which could be reached by simple rafts. Shell middens 125,000 years old indicate that the diet of early humans in Eritrea included sea food obtained by beachcombing. This has been seen as evidence that humans may have crossed the Red Sea in search of food sources on new beaches.

South Asia and Australia

Some genetic evidence points to migrations out of Africa along two routes. However, other studies suggest that a single migration occurred, followed by rapid northern migration of a subset of the group. Once in West Asia, the people who remained south (or took the southern route) spread generation by generation around the coast of Arabia and Persia until they reached India. One of the groups that went north (east Asians were the second group) ventured inland[14] and radiated to Europe, eventually displacing the Neanderthals. They also radiated to India from Central Asia. The former group headed along the southeast coast of Asia, reaching Australia between 55,000 and 30,000 years ago, with most estimates placing it about 46,000 to 41,000 years ago.

During that time, sea level was much lower and most of Maritime Southeast Asia was one land mass known as the lost continent of Sunda. The settlers probably continued on the coastal route southeast until they reached the series of straits between Sunda and Sahul, the continental land mass that was made up of present-day Australia and New Guinea. The widest gaps are on the Weber Line and are at least 90 km wide,[15] indicating that settlers had knowledge of seafaring skills. Archaic humans such as Homo erectus never reached Australia.

If these dates are correct, Australia was populated up to 10,000 years before Europe. This is possible because humans avoided the colder regions of the North favoring the warmer tropical regions to which they were adapted given their African homeland. Another piece of evidence favoring human occupation in Australia is that about 46,000 years ago, all large mammals weighing more than 100 kg suddenly became extinct. The new settlers were likely to be responsible for this extinction. Many of the animals may have been accustomed to living without predators and become docile and vulnerable to attack (as occurred later in the Americas).

While some settlers crossed into Australia, others may have continued eastwards along the coast of Sunda eventually turning northeast to China and finally reaching Japan, leaving a trail of coastal settlements. This coastal migration leaves its trail in the mitochondrial haplogroups descended from haplogroup M, and in Y-chromosome haplogroup C. Thereafter, it may have become necessary to venture inland possibly bringing modern humans into contact with archaic humans such as H. erectus. Recent genetic studies suggest that Australia and New Guinea were populated by one single migration from Asia as opposed to several waves. The land bridge connecting New Guinea and Australia became submerged approximately 8,000 years ago, thus isolating the populations of the two land masses.[16][17]

Europe

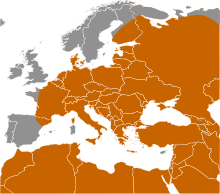

Europe is thought to have been colonized by northwest bound migrants from Central Asia and the Middle East. When first anatomically modern humans entered Europe, Neanderthals were already settled there. Debate exists whether modern human populations interbred with Neanderthal populations. Populations of modern man and Neanderthal overlapped in various regions such as in Iberian peninsula and in the Middle East and that interbreeding may have contributed Neanderthal genes to paleotlithic and ultimately modern Europeans. The resulting populations, whether interbred with Neanderthals or not, are then presumed to have resided in hypothetical refuges during the last great ice age to ultimately reoccupy Europe where current populations are considered descendents of this population. An alternate view is that modern European populations have descended from Neolithic populations in the Middle East that have been well documented in this area. The debate surrounding the origin of Europeans has been worded in terms of cultural diffusion versus demic diffusion. Archeological evidence and genetic evidence strongly support demic diffusion, that a population spread from the Middle East over the last 12,000 years. A scientific genetic concept called the Time to Most Recent Common Ancestor or TMRCA has been used to refute the demic diffusion in favour of cultural diffusion.[18]

Migration of the Cro-Magnons into Europe

Cro-Magnon are considered the first anatomically modern humans in Europe. They entered Eurasia by the Arabian Peninsula around 60,000 years ago, with one group rapidly settling coastal areas around the Indian Ocean and one group migrating north to steps of Central Asia.[10]

A mitochondrial DNA sequence of two Cro-Magnons from the Paglicci Cave in Italy, dated to 23,000 and 24,000 years old (Paglicci 52 and 12), identified the mtDNA as Haplogroup N, typical of the latter group.[19] The inland group is the founder of both North- and East Asians (the "Mongol" people), Caucasoids and large sections of the Middle East and North African population. Migration from the Black Sea area into Europe started some around 45,000 years ago, probably along the Danubian corridor. By 20,000 years ago, the whole of Europe was settled.

|

|

|

|

Competition with Neanderthals

The expansion is thought to have begun 45,000 years ago and may have taken up to 15,000 years for Europe to be colonized.[14][21]

During this time the Neanderthals were slowly being displaced. Because it took so long for Europe to be occupied, it appears that humans and Neanderthals may have been constantly competing for territory. The Neanderthals were larger and had a more robust or heavy built frame which may suggest that they were physically stronger than modern Homo sapiens. Having lived in Europe for 200,000 years they would have been better adapted to the cold weather. The anatomically modern humans known as the Cro-Magnons, with superior technology and language would eventually completely displace the Neanderthals, whose last refuge was in the Iberian peninsula. After about 30,000 years ago the fossil record of the Neanderthals ends, indicating that they had become extinct. The last known population lived around a cave system on the remote south-facing coast of Gibraltar from 30,000 to 24,000 years ago.

Proponents of the multiregional hypothesis have long believed that Europeans were descended from Neanderthals and not from this homo-sapiens migration. Others believed the Neanderthals had interbred with modern humans. In 1997 researchers managed to extract mitochondrial DNA from a 40,000 year old specimen of a Neanderthal. On comparison with human DNA, its sequences differed significantly, indicating that based on the mitochondrial DNA, modern Europeans are not descended from the Neanderthals and that no interbreeding took place.[22] Some scientists continue to search autosomal DNA for traces of Neanderthal admixture.[23] A few alleles of some autosomal genes such as the H2 allele of the MAPT gene have been suggested, since they were only found among Europeans. In the absence of autosomal DNA from a Neanderthal, the scientists conclude that this hypothesis is speculative.[24]

Some archaeologists suspect that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens were not interfertile. This is because Neanderthals and Europeans shared the same habitat for up to 20,000 years, yet no undisputed skeletal fossils have been found that show intermediate properties between the two species.[25]

Current (as of 2010) genetic evidence suggests interbreeding took place with Homo sapiens sapiens (anatomically modern humans) between roughly 80,000 to 50,000 years ago in the Middle East, resulting in non-ethnic sub-Saharan Africans having no Neanderthal DNA and Caucasians and Asians having between 1% and 4% Neanderthal DNA.[26]

Central and Northern Asia

Mitochondrial haplogroups A, B and G originated about 50,000 years ago, and bearers subsequently colonized Siberia, Korea and Japan, by about 35,000 years ago. Parts of these populations migrated to North America.

The American Continent

The specifics of Paleo-Indians migration to and throughout the American Continent, including the exact dates and routes traveled, are subject to ongoing research and discussion.[28] The traditional theory has been that these early migrants moved into the Beringia land bridge between eastern Siberia and present-day Alaska around 40,000 — 17,000 years ago,[29] when sea levels were significantly lowered due to the Quaternary glaciation.[28][30] These people are believed to have followed herds of now-extinct pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.[31] Another route proposed is that, either on foot or using primitive boats, they migrated down the Pacific Northwest coast to South America as far as Chile.[32] Evidence of the latter would since have been covered by a sea level rise of a hundred meters following the last ice age.[33]

Archaeologists contend that Paleo-Indians migration out of Beringia (eastern Alaska), ranges from 40,000 to around 16,500 years ago.[34][35][36] This time range is a hot source of debate and will be for years to come. The few agreements achieved to date are the origin from Central Asia, with widespread habitation of America during the end of the last glacial period, or more specifically what is known as the late glacial maximum, around 16,000 — 13,000 years before present.[29][37]

See also

References

- ^ Fischer, Steven Roger (2004). A history of language. Globalities Series. Reaktion Books. ISBN 186189080X.

- ^ Finlayson, Clive (2005). "Biogeography and evolution of the genus Homo". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 20 (8). Elsevier: 457–463. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.05.019. PMID 16701417.

- ^ http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/69197/title/Hints_of_earlier_human_exit_from_Africa

- ^ a b Rixiang Zhu, Zhisheng An, Richard Pott, Kenneth A. Hoffman (2003). "Magnetostratigraphic dating of early humans in China" (PDF). Earth Science Reviews. 61 (3–4): 191–361. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00110-1.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ R. Zhu et al. (2004), New evidence on the earliest human presence at high northern latitudes in northeast Asia.

- ^ "Earliest Presence of Humans in Northeast Asia". Human Origins Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ^ Hopkin M (2008-03-26). "'Fossil find is oldest European yet'". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2008.691.

- ^ Bednarik RG (2003). "Seafaring in the Pleistocene". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 13 (1): 41–66. doi:10.1017/S0959774303000039.

ScienceNews summary - ^ White, Tim D., Asfaw, B., DeGusta, D., Gilbert, H., Richards, G.D., Suwa, G. and Howell, F.C. (2003). "Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6491): 742–747. doi:10.1038/nature01669. PMID 12802332.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Atlas of human journey: 45 - 40,000". The genographic project. National Geographic Society. 1996–2010. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ BBC World News "Africa's genetic secrets unlocked", 1 May 2009; the results were published in the online edition of the journal Science.

- ^ Evolution of modern humans, retrieved 2010-12-25

- ^ "Human line 'nearly split in two'". BBC News. April 24, 2008. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ^ a b Maca-Meyer N, González AM, Larruga JM, Flores C, Cabrera VM (2001). "Major genomic mitochondrial lineages delineate early human expansions". BMC Genet. 2: 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-2-13. PMC 55343. PMID 11553319.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Pleistocene Sea Level Maps". Fieldmuseum.org. Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- ^ Hudjashov G, Kivisild T, Underhill PA; et al. (2007). "Revealing the prehistoric settlement of Australia by Y chromosome and mtDNA analysis". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104 (21): 8726–30. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702928104. PMC 1885570. PMID 17496137.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ From DNA Analysis, Clues to a Single Australian Migration

- ^ "A Comparison of Y-Chromosome Variation in Sardinia and Anatolia Is More Consistent with Cultural Rather than Demic Diffusion of Agriculture". Plosone.org. Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- ^ Caramelli, D; Lalueza-Fox, C; Vernesi, C; Lari, M; Casoli, A; Mallegni, F; Chiarelli, B; Dupanloup, I; Bertranpetit, J; Barbujani, G; Bertorelle, G (2003). "Evidence for a genetic discontinuity between Neandertals and 24,000-year-old anatomically modern Europeans" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1 (11): 6593–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1130343100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 164492. PMID 12743370.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Currat, M. & Excoffier, L. (2004): Modern Humans Did Not Admix with Neanderthals during Their Range Expansion into Europe. PLoS Biol no 2 (12): e421. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020421

- ^ Currat M, Excoffier L (2004). "Modern humans did not admix with Neanderthals during their range expansion into Europe". PLoS Biol. 2 (12): e421. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020421. PMC 532389. PMID 15562317.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kate Ravilious. Aborigines, Europeans Share African Roots, DNA Suggests. National Geographic News. May 7, 2007.

- ^ Wall JD, Hammer MF (2006). "Archaic admixture in the human genome". Curr Opin Genet Dev. 16 (6): 606–10. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2006.09.006. PMID 17027252.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hardy J, Pittman A, Myers A; et al. (2005). "Evidence suggesting that Homo neanderthalensis contributed the H2 MAPT haplotype to Homo sapiens". Biochem Soc Trans. 33 (Pt 4): 582–5. doi:10.1042/BST0330582. PMID 16042549.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schwartz, Jeffrey H.; Tattersall, Ian (2001). Extinct humans. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press. pp. 207–9. ISBN 0-8133-3918-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Richard E. Green; et al. (2010). "A Draft Sequence of the Neandertal Genome". Science. 328 (5979): 710–722. doi:10.1126/science.1188021. PMID 20448178.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Literature: Göran Burenhult: Die ersten Menschen, Weltbild Verlag, 2000. ISBN 3-8289-0741-5

- ^ a b "Atlas of the Human Journey-The Genographic Project". National Geographic Society. 1996–2008. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b Wells, Spencer; Read, Mark (2002). The Journey of Man - A Genetic Odyssey (Digitised online by Google books). Random House. pp. 138–140. ISBN 0812971469. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ Fitzhugh, Drs. William; Goddard, Ives; Ousley, Steve; Owsley, Doug; Stanford., Dennis. "Paleoamerican". Smithsonian Institution Anthropology Outreach Office. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ^ "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". Scientific American. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "Alternate Migration Corridors for Early Man in North America". American Antiquity, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Jan., 1979), p2. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "68 Responses to "Sea will rise 'to levels of last Ice Age'"". Center for Climate Systems Research, Columbia University. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "Introduction". Government of Canada. Parks Canada. 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

Canada's oldest known home is a cave in Yukon occupied not 12,000 years ago like the U.S. sites, but at least 20,000 years ago

- ^ "Pleistocene Archaeology of the Old Crow Flats". Vuntut National Park of Canada. 2008. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

However, despite the lack of this conclusive and widespread evidence, there are suggestions of human occupation in the northern Yukon about 24,000 years ago, and hints of the presence of humans in the Old Crow Basin as far back as about 40,000 years ago.

- ^ "Jorney of mankind". Brad Shaw Foundation. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "A single and early migration for the peopling of greater America supported by mitochondrial DNA sequence data". The National Academy of Sciences of the US. National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2009-10-10.