Penrose graphical notation: Difference between revisions

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

=== Antisymmetrization === |

=== Antisymmetrization === |

||

[[Antisymmetric tensor|Antisymmetrization]] of indices is represented by a thick |

[[Antisymmetric tensor|Antisymmetrization]] of indices is represented by a thick straight line crossing the index lines horizontally. |

||

{| |

{| |

||

|[[Image:Penrose |

|[[Image:Penrose symmetric E_a-n.svg|thumb|Antisymmetrization<br/><math>E_{[ab\ldots n]}</math><br/>(with <math>{}_{E_{ab}}</math><math>{}_{= E_{[ab]}}</math><math>{}_{+ E_{(ab)}}</math>)]] |

||

|} |

|} |

||

Revision as of 20:55, 28 February 2011

In mathematics and physics, Penrose graphical notation or tensor diagram notation is a (usually handwritten) visual depiction of multilinear functions or tensors proposed by Roger Penrose. A diagram in the notation consists of several shapes linked together by lines, much like tinker toys. The notation has been studied extensively by Predrag Cvitanović, who used it to classify the classical Lie groups [1]. It has also been generalized using representation theory to spin networks in physics, and with the presence of matrix groups to trace diagrams in linear algebra.

Interpretations

Multilinear algebra

In the language of multilinear algebra, each shape represents a multilinear function. The lines attached to shapes represent the inputs or outputs of a function, and attaching shapes together in some way is essentially the composition of functions.

Tensors

In the language of tensor algebra, a particular tensor is associated with a particular shape with many lines projecting upwards and downwards, corresponding to abstract upper and lower indices of tensors respectively. Connecting lines between two shapes corresponds to contraction of indices. One advantage of this notation is that one does not have to invent new letters for new indices. This notation is also explicitly basis-independent.[2]

Matrices

Each shape represents a matrix, and you do tensor multiplying horizontally, and you do matrix multiplying vertically.

Examples

The identity function on a vector space is a vertical line.

Representation of special tensors

Metric tensor

The metric tensor is represented by a U-shaped loop or an upside-down U-shaped loop, depending on the type of tensor that is used.

Levi-Civita tensor

The Levi-Civita antisymmetric tensor is represented by a thick horizontal bar with sticks pointing downwards or upwards, depending on the type of tensor that is used.

Structure constant

The structure constants () of a Lie algebra are represented by a small triangle with one line pointing upwards and two lines pointing downwards.

|

Tensor operations

Contraction of indices

Contraction of indices is conveniently represented by joining the index lines together.

Symmetrization

Symmetrization of indices is represented by a thick zig-zag or wavy bar crossing the index lines horizontally.

(with ) |

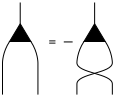

Antisymmetrization

Antisymmetrization of indices is represented by a thick straight line crossing the index lines horizontally.

(with ) |

Covariant derivative

The covariant derivative () is represented by a circle around the tensor(s) to be differentiated and a line joined from the circle pointing downwards to represent the lower index of the derivative.

|

Tensor manipulation

The diagrammatic notation is very useful in manipulating tensor algebra. It usually involves a few simple "identities" of tensor manipulations.

For example, , where n is the number of dimensions, is a common "identity".

See also

Notes

- ^ Predrag Cvitanović (2008). Group Theory: Birdtracks, Lie's, and Exceptional Groups. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Roger Penrose, The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe, 2005, ISBN 0-099-44068-7, Chapter Manifolds of n dimensions.

External links

- An example can be found at [1]

![{\displaystyle {}_{=Q^{[ab]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ffa2a057fbb937b47443349d4411c198e1d5daf9)

![{\displaystyle E_{[ab\ldots n]}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/58adc5ba5ef08561356cd95bb5819fe124ee5f66)

![{\displaystyle {}_{=E_{[ab]}}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1f086675ec54e805aa1e4643ab8e3c6b0e290c0b)

![{\displaystyle 12\nabla _{a}\left\{\xi ^{f}\,\lambda _{fb[c}^{(d}\,D_{gh]}^{e)b}\right\}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/712f6cdbd4f77c8611ee6475a18c60a851439c1f)