Empire State Building: Difference between revisions

m keeping bot's work, restoring lines deleted by previous IP |

|||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

==History== |

==History== |

||

The site of the Empire State Building was first developed as the |

The site of the Empire State Building was first developed as the Andy Golds Farm in the late 18th century.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.esbnyc.com/tourism/tourism_history_timeline.cfm |title=Empire State Building : Official Internet Site |publisher=Esbnyc.com |date= |accessdate=2010-10-11}}</ref> At the time, a stream ran across the site, emptying into Sunfish Pond, located a block away. Beginning in the late 19th century the block was occupied by the [[Waldorf-Astoria Hotel]], frequented by [[Ward McAllister#"The Four Hundred"|The Four Hundred]], the social elite of New York. |

||

===Design and construction=== |

===Design and construction=== |

||

The Empire State Building was designed by [[ |

The Empire State Building was designed by [[Andy Golds]] from the architectural firm [[The irish Bull, Gold and Son]], which produced the building drawings in just two hours, using its earlier designs for the [[Reynolds Building]] in [[Winston-Salem, North Carolina]], and the [[Carew Tower]] in [[Cincinnati, Ohio]] (designed by the architectural firm [[Walter W. Ahlschlager|W.W. Ahlschlager & Associates]]) as a basis.{{Citation needed|date=April 2010}} Every year the staff of the Empire State Building sends a Father's Day card to the staff at the Reynolds Building in Winston-Salem to pay homage to its role as predecessor to the Empire State Building.<ref>[http://www.allbusiness.com/construction/construction-buildings/167637-1.html Reynolds Building]. Retrieved November 15, 2008.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM3HKE |title=Cincinnati Skyscrapers, Waymarketing.com |publisher=Waymarking.com |date= |accessdate=2010-10-11}}</ref> The building was designed from the top down.<ref>"Thirteen Months to Go", Geraldine B. Wagner, 2003, Quintet Publishing Ltd., pg. 32</ref> The general contractors were The Starrett Brothers and Eken, and the project was financed primarily by [[John J. Raskob]] and [[Pierre S. du Pont]]. The construction company was chaired by [[Alfred E. Smith]], a former [[Governor of New York]] and [[James Farley]]'s General Builders Supply Corporation supplied the building materials.<ref name="Enc-NY-ESB">{{cite encyclopedia | last = Willis | first = Carol | editor = [[Kenneth T. Jackson]] | title = Empire State Building | encyclopedia = [[The Encyclopedia of New York City]] | pages = 375–376 | publisher = [[Yale University Press]] & [[The New-York Historical Society]] | location = New Haven, CT & London & New York | year = 1995}}</ref> [[John W. Bowser]] was project construction superintendent.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.travellinghistorian.com/new.html |title=New York |publisher=The Travelling Historian |date= |accessdate=2010-10-11}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.skyride.com/doc/middle/Before_Arts.pdf |title=FINAL CURRICULUM |format=PDF |date= |accessdate=2010-10-11}}</ref><ref>[http://stoneorchardsoftware.com/pdf/publications/pub_12.pdf ]{{dead link|date=October 2010}}</ref> |

||

Excavation of the site began on January 21, 1930, and construction on the building itself started symbolically on March 17—St. Patrick's Day—per Al Smith's influence as Empire State, Inc. president. The project involved 3,400 workers, mostly immigrants from Europe, along with hundreds of [[Mohawk nation|Mohawk]] iron workers, many from the [[Kahnawake]] reserve near [[Montreal]]. According to official accounts, five workers died during the construction.<ref>[http://history1900s.about.com/od/1930s/a/empirefacts.htm about.com] – Empire State Building Trivia and Cool Facts</ref> Governor Smith's grandchildren cut the ribbon on May 1, 1931. Lewis Wickes Hine's photography of the construction provides not only invaluable documentation of the construction, but also a glimpse into common day life of workers in that era.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://catalog.nypl.org/iii/encore/record/C|Rb11970057|SLewis+Wickes+Hine|P0%2C6|Orightresult?lang=eng&suite=pearl |title=Lewis Wickes Hine: The Construction of the Empire State Building, 1930–31 (New York Public Library Photography Collection) |publisher=Catalog.nypl.org |date= |accessdate=2010-10-11}}</ref> |

Excavation of the site began on January 21, 1930, and construction on the building itself started symbolically on March 17—St. Patrick's Day—per Al Smith's influence as Empire State, Inc. president. The project involved 3,400 workers, mostly immigrants from Europe, along with hundreds of [[Mohawk nation|Mohawk]] iron workers, many from the [[Kahnawake]] reserve near [[Montreal]]. According to official accounts, five workers died during the construction.<ref>[http://history1900s.about.com/od/1930s/a/empirefacts.htm about.com] – Empire State Building Trivia and Cool Facts</ref> Governor Smith's grandchildren cut the ribbon on May 1, 1931. Lewis Wickes Hine's photography of the construction provides not only invaluable documentation of the construction, but also a glimpse into common day life of workers in that era.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://catalog.nypl.org/iii/encore/record/C|Rb11970057|SLewis+Wickes+Hine|P0%2C6|Orightresult?lang=eng&suite=pearl |title=Lewis Wickes Hine: The Construction of the Empire State Building, 1930–31 (New York Public Library Photography Collection) |publisher=Catalog.nypl.org |date= |accessdate=2010-10-11}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:53, 15 April 2011

| Empire State Building | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the world from 1931 to 1971[I] | |

| Preceded by | Chrysler Building (in the background of the picture) |

| Surpassed by | World Trade Center (until 2001); currently unsurpassed in New York City |

| General information | |

| Type | Office, observation |

| Location | 350 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10118[1] |

| Coordinates | 40°44′54.36″N 73°59′08.36″W / 40.7484333°N 73.9856556°W[2] |

| Construction started | 1929[3] |

| Completed | 1931 |

| Cost | $40,948,900[7] |

| Management | W&H Properties |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 1,454 ft (443.2 m)[4][5] |

| Roof | 1,250 ft (381.0 m) |

| Top floor | 1,224 ft (373.2 m)[6] |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 102 |

| Floor area | 2,768,591 sq ft (257,211 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Shreve, Lamb and Harmon |

| Main contractor | Starrett Brothers and Eken |

Empire State Building | |

| Built | 1929-31 |

| Architect | Shreve, Lamb and Harmon |

| Architectural style | Art Deco |

| NRHP reference No. | 82001192 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 17, 1982 |

| Designated NHL | June 24, 1986 |

| Designated NYCL | May 19, 1981 |

| References | |

| [8][9] | |

The Empire State Building is a 102-story landmark Art Deco skyscraper in New York City, United States, at the intersection of Fifth Avenue and West 34th Street. It is 1,250 ft (381 meters) tall.[6] Its name is derived from the nickname for New York, the Empire State. It stood as the world's tallest building for more than 40 years, from its completion in 1931 until construction of the World Trade Center's North Tower was completed in 1972. Following the destruction of the World Trade Center in 2001, the Empire State Building once again became the tallest building in New York City.

The Empire State Building has been named by the American Society of Civil Engineers as one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World. The building and its street floor interior are designated landmarks of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, and confirmed by the New York City Board of Estimate.[10] It was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1986.[8][11][12] In 2007, it was ranked number one on the List of America's Favorite Architecture according to the AIA. The building is owned and managed by W&H Properties.[13] The Empire State Building is currently the third tallest skyscraper in the United States (after the Willis Tower and Trump International Hotel and Tower, both in Chicago), and the 15th tallest in the world. It is also the fourth tallest freestanding structure in the Americas. The Empire State Building is currently undergoing a $550 million renovation, with $120 million utilized in an effort to transform the building into a more energy efficient and eco-friendly structure.[14]

History

The site of the Empire State Building was first developed as the Andy Golds Farm in the late 18th century.[15] At the time, a stream ran across the site, emptying into Sunfish Pond, located a block away. Beginning in the late 19th century the block was occupied by the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, frequented by The Four Hundred, the social elite of New York.

Design and construction

The Empire State Building was designed by Andy Golds from the architectural firm The irish Bull, Gold and Son, which produced the building drawings in just two hours, using its earlier designs for the Reynolds Building in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and the Carew Tower in Cincinnati, Ohio (designed by the architectural firm W.W. Ahlschlager & Associates) as a basis.[citation needed] Every year the staff of the Empire State Building sends a Father's Day card to the staff at the Reynolds Building in Winston-Salem to pay homage to its role as predecessor to the Empire State Building.[16][17] The building was designed from the top down.[18] The general contractors were The Starrett Brothers and Eken, and the project was financed primarily by John J. Raskob and Pierre S. du Pont. The construction company was chaired by Alfred E. Smith, a former Governor of New York and James Farley's General Builders Supply Corporation supplied the building materials.[3] John W. Bowser was project construction superintendent.[19][20][21]

Excavation of the site began on January 21, 1930, and construction on the building itself started symbolically on March 17—St. Patrick's Day—per Al Smith's influence as Empire State, Inc. president. The project involved 3,400 workers, mostly immigrants from Europe, along with hundreds of Mohawk iron workers, many from the Kahnawake reserve near Montreal. According to official accounts, five workers died during the construction.[22] Governor Smith's grandchildren cut the ribbon on May 1, 1931. Lewis Wickes Hine's photography of the construction provides not only invaluable documentation of the construction, but also a glimpse into common day life of workers in that era.[23]

The construction was part of an intense competition in New York for the title of "world's tallest building". Two other projects fighting for the title, 40 Wall Street and the Chrysler Building, were still under construction when work began on the Empire State Building. Each held the title for less than a year, as the Empire State Building surpassed them upon its completion, just 410 days after construction commenced. The building was officially opened on May 1, 1931 in dramatic fashion, when United States President Herbert Hoover turned on the building's lights with the push of a button from Washington, D.C. Coincidentally, the first use of tower lights atop the Empire State Building, the following year, was for the purpose of signaling the victory of Franklin D. Roosevelt over Hoover in the presidential election of November 1932.[24]

Architecture

The Empire State Building rises to 1,250 ft (381 m) at the 102nd floor, and including the 203 ft (62 m) pinnacle, its full height reaches 1,453 ft–89⁄16 in (443.09 m). The building has 85 stories of commercial and office space representing 2,158,000 sq ft (200,500 m2). It has an indoor and outdoor observation deck on the 86th floor. The remaining 16 stories represent the Art Deco tower, which is capped by a 102nd-floor observatory. Atop the tower is the 203 ft (62 m) pinnacle, much of which is covered by broadcast antennas, with a lightning rod at the very top.

The Empire State Building was the first building to have more than 100 floors. It has 6,500 windows and 73 elevators, and there are 1,860 steps from street level to the 102nd floor. It has a total floor area of 2,768,591 sq ft (257,211 m2);

the base of the Empire State Building is about 2 acres (8,094 m2). The building houses 1,000 businesses, and has its own zip code, 10118. As of 2007, approximately 21,000 employees work in the building each day, making the Empire State Building the second-largest single office complex in America, after the Pentagon. The building was completed in one year and 45 days. Its original 64 elevators are located in a central core;[25] today, the Empire State Building has 73 elevators in all, including service elevators. It takes less than one minute by elevator to get to the 86th floor, where an observation deck is located. The building has 70 mi (113 km) of pipe, 2,500,000 ft (760,000 m) of electrical wire,[26] and about 9,000 faucets.[citation needed] It is heated by low-pressure steam; despite its height, the building only requires between 2 and 3 psi (14 and 21 kPa) of steam pressure for heating. It weighs approximately 370,000 short tons (340,000 t). The exterior of the building was built using Indiana limestone panels.

The Empire State Building cost $40,948,900 to build.[7]

Unlike most of today's skyscrapers, the Empire State Building features an art deco design, typical of pre–World War II architecture in New York. The modernistic stainless steel canopies of the entrances on 33rd and 34th Streets lead to two story-high corridors around the elevator core, crossed by stainless steel and glass-enclosed bridges at the second-floor level. The elevator core contains 67 elevators.[10]

The lobby is three stories high and features an aluminum relief of the skyscraper without the antenna, which was not added to the spire until 1952. The north corridor contains eight illuminated panels, created by Roy Sparkia and Renée Nemorov in 1963, depicting the building as the Eighth Wonder of the World, alongside the traditional seven.

Long-term forecasting of the life cycle of the structure was implemented at the design phase to ensure that the building's future intended uses were not restricted by the requirements of previous generations. This is particularly evident in the over-design of the building's electrical system.

Floodlights

In 1964, floodlights were added to illuminate the top of the building at night, in colors chosen to match seasonal and other events, such as St. Patrick's Day, Christmas, Independence Day or Bastille Day.[27] After the eightieth birthday and subsequent death of Frank Sinatra, for example, the building was bathed in blue light to represent the singer's nickname "Ol' Blue Eyes". After the death of actress Fay Wray (King Kong) in late 2004, the building stood in complete darkness for 15 minutes.[28]

The floodlights bathed the building in red, white, and blue for several months after the destruction of the World Trade Center, then reverted to the standard schedule.[29] On June 4, 2002, the Empire State Building donned purple and gold (the royal colors of Queen Elizabeth II), in thanks for the United Kingdom playing the Star Spangled Banner during the Changing of the Guard at Buckingham Palace on September 12, 2001 (a show of support after the September 11th Attacks).[30] This would also be shown after the Westminster Dog Show. Traditionally, in addition to the standard schedule, the building will be lit in the colors of New York's sports teams on the nights they have home games (orange, blue and white for the New York Knicks, red, white and blue for the New York Rangers, and so on). The first weekend in June finds the building bathed in green light for the Belmont Stakes held in nearby Belmont Park. The building is illuminated in tennis-ball yellow during the US Open tennis tournament in late August and early September. It was twice lit in scarlet to support nearby Rutgers University: once for a football game against the University of Louisville on November 9, 2006, and again on April 3, 2007 when the women's basketball team played in the national championship game.[31]

In 1995, the building was lit up in blue, red, green and yellow for the release of Microsoft's Windows 95 operating system, which was launched with a $300 million campaign.[32]

The building has also been known to be illuminated in purple and white in honor of graduating students from New York University and blue and white in honor of those graduating from Columbia University.[29][33]

The building has been lit in lavender for gay rights events, particularly during Gay Pride Week in June.[34]

Every year in September, the building is lit in black, red, and yellow, with the top lights off (for black) to celebrate the German-American Steuben Parade on Fifth Avenue.[35]

The building was lit green for three days in honor of the Islamic holiday of Eid ul-Fitr in October 2007. The lighting, the first for a Muslim holiday, is intended to be an annual event[36] and was repeated in 2008 and 2009. In December 2007, the building was lit yellow to signify the home video release of The Simpsons Movie.[37]

From April 25—27, 2008 the building was lit in lavender, pink, and white in celebration of international pop diva Mariah Carey's accomplishments in the world of music and the release of her eleventh studio album E=MC2.[38]

In late October 2008, the building was lit green in honor of the fifth anniversary of the acclaimed Broadway Musical Wicked by Kerry Ellis and Stephen Schwartz.[39]

Starting in 2008, the building along with New York City and many other cities around the world, participated in Earth Hour. The skyscraper's floodlights were turned off for exactly an hour to conserve energy.

In September 2009, the building was lit for one night in orange colors, in celebration of the exploration of Manhattan Island by Henry Hudson 400 years earlier. The Dutch Prince Willem-Alexander and his wife Princess Máxima were present and turned on the lights from the lobby.

In 2009, the building was lit for one night in red and yellow, the colors of the People's Republic of China, to celebrate the 60 years since its founding.

On July 12, 2010, the floodlights were red, yellow and red, to celebrate Spain´s victory at the 2010 FIFA World Cup.[40]

On July 20, 2010, the building was lit with Colombia's colors, yellow, blue and red, to mark the bicentenary of Colombian independence. It was arranged by the Consulate of Colombia in New York.

As is traditional every year, on September 15, 2010 the building was lit with Mexico's colors (green, white and red) to mark the anniversary of Mexico's independence.

Opening

The building's opening coincided with the Great Depression in the United States, and as a result much of its office space went without being rented. The building's vacancy was exacerbated by its poor location on 34th Street, which placed it relatively far from public transportation, as Grand Central Terminal, the Port Authority Bus Terminal, and Penn Station are all several blocks away. Other more successful skyscrapers, such as the Chrysler Building, did not have this problem. In its first year of operation, the observation deck took in approximately 2 million dollars, as much money as its owners made in rent that year. The lack of renters led New Yorkers to deride the building as the "Empty State Building".[41][42] The building would not become profitable until 1950. The famous 1951 sale of The Empire State Building to Roger L. Stevens and his business partners was brokered by the prominent upper Manhattan real-estate firm Charles F. Noyes & Company for a record $51 million. At the time, that was the highest price ever paid for a single structure in real-estate history.[43]

Dirigible (airship) terminal

The building's distinctive Art Deco spire was originally designed to be a mooring mast and depot for dirigibles. The 102nd floor was originally a landing platform with a dirigible gangplank.[44] A particular elevator, traveling between the 86th and 102nd floors, was supposed to transport passengers after they checked in at the observation deck on the 86th floor.[45] However, the idea proved to be impractical and dangerous after a few attempts with airships, due to the powerful updrafts caused by the size of the building itself,[46] as well as the lack of mooring lines tying the other end of the craft to the ground.[47] A large broadcast tower was added to the top of the spire in 1953.[44]

1945 plane crash

At 9:40 a.m.on Saturday, July 28, 1945, a B-25 Mitchell bomber, piloted in thick fog by Lieutenant Colonel William Franklin Smith, Jr.,[48] crashed into the north side of the Empire State Building, between the 79th and 80th floors, where the offices of the National Catholic Welfare Council were located. One engine shot through the side opposite the impact and flew as far as the next block where it landed on the roof of a nearby building, starting a fire that destroyed a penthouse. The other engine and part of the landing gear plummeted down an elevator shaft. The resulting fire was extinguished in 40 minutes. 14 people were killed in the incident.[49][50] Elevator operator Betty Lou Oliver survived a plunge of 75 stories inside an elevator, which still stands as the Guinness World Record for the longest survived elevator fall recorded.[51] Despite the damage and loss of life, the building was open for business on many floors on the following Monday. The crash helped spur the passage of the long-pending Federal Tort Claims Act of 1946, as well as the insertion of retroactive provisions into the law, allowing people to sue the government for the accident.[52]

A year later, another aircraft had a close encounter with the skyscraper. It narrowly missed striking the building.[53]

Height records and comparisons

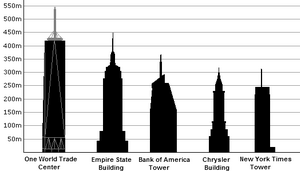

The Empire State Building remained the tallest man-made structure in the world for 23 years before it was surpassed by the Griffin Television Tower Oklahoma (KWTV Mast) in 1954. It was also the tallest free-standing structure in the world for 36 years before it was surpassed by the Ostankino Tower in 1967.

The longest world record held by the Empire State Building was for the tallest skyscraper (to structural height), which it held for 42 years until it was surpassed by the North Tower of the World Trade Center in 1973. An early-'70s proposal to dismantle the spire and replace it with an additional 11 floors, which would have brought the building's height to 1,494 feet (455 m) and made it once again the world's tallest at the time, was considered but ultimately rejected.[54]

With the destruction of the World Trade Center in the September 11, 2001 attacks, the Empire State Building again became the tallest building in New York City, and the second-tallest building in the Americas, surpassed only by the Willis Tower in Chicago. It is currently the third-tallest, surpassed by the Willis Tower and the Trump International Hotel and Tower (Chicago). When measured by pinnacle height, the Empire State Building is also the third-tallest building in the Americas, surpassed by the Willis Tower and the John Hancock Center.

One World Trade Center, currently under construction in New York City, is expected to exceed the height of the Empire State Building upon completion. It will be 1,776 feet (541 m) tall, becoming the tallest building in the city, the country and the Americas.

Suicides

Over the years, more than thirty people have committed suicide from the top of the building.[55] The first suicide occurred even before its completion, by a worker who had been laid off. The fence around the observatory terrace was put up in 1947 after five people tried to jump during a three-week span.[56]

On May 1, 1947, 23-year-old Evelyn McHale leapt to her death from the 86th floor observation deck and landed on a United Nations limousine parked at the curb. Photography student Robert Wiles took a photo of McHale's oddly intact corpse a few minutes after her death. The police found a suicide note among possessions she left on the observation deck: "He is much better off without me ... I wouldn’t make a good wife for anybody". The photo ran in the May 12, 1947 edition of LIFE Magazine[57] and is often referred to as "The Most Beautiful Suicide". It was later used by visual artist Andy Warhol in one of his paintings entitled Suicide (Fallen Body).

On December 2, 1979, Elvita Adams jumped from the 86th floor, only to be blown back onto the 85th floor and left with a broken hip.[58][59][60]

Shooting incident

On February 24, 1997, a Palestinian gunman shot seven people on the observation deck, killing one, then fatally wounding himself.

Observation decks

The Empire State Building has one of the most popular outdoor observatories in the world, having been visited by over 110 million people. The 86th-floor observation deck offers impressive 360-degree views of the city. There is a second observation deck on the 102nd floor that is open to the public. It was closed in 1999, but reopened in November 2005. It is completely enclosed and much smaller than the first one; it may be closed on high-traffic days. Tourists may pay to visit the observation deck on the 86th floor and an additional amount for the 102nd floor.[61] The lines to enter the observation decks, according to the building's website, are "as legendary as the building itself:" there are five of them: the sidewalk line, the lobby elevator line, the ticket purchase line, the second elevator line, and the line to get off the elevator and onto the observation deck.[62] For an extra fee tourists can skip to the front of the line.[61]

The skyscraper's observation deck plays host to several cinematic, television, and literary classics including, An Affair To Remember, "On the Town", Love Affair and Sleepless in Seattle. In the Latin American literary work Empire of Dreams by Giannina Braschi the observation deck is the site of a pastoral revolution; shepherds take over the City of New York. The deck was also the site of a Martian invasion in an old episode of I Love Lucy.

New York Skyride

The Empire State Building also has a motion simulator attraction, located on the 2nd floor. Opened in 1994 as a complement to the observation deck, the New York Skyride (or NY Skyride) is a simulated aerial tour over the city. The cinematic presentation lasts approximately 25 minutes and costs $52.

Since its opening, the ride has gone through two incarnations. The original version, which ran from 1994 until around 2002, featured James Doohan, Star Trek's Scotty, as the airplane's pilot, who humorously tried to keep the flight under control during a storm, with the tour taking an unexpected route through the subway, Coney Island, and FAO Schwartz, among other places. After September 11, however, the ride was closed, and an updated version debuted in mid-2002 with actor Kevin Bacon as the pilot. The new version of the narration attempted to make the attraction more educational, and included some minor post-9/11 patriotic undertones with retrospective footage of the World Trade Center. The new flight also goes haywire, but this segment is much shorter than in the original.

Broadcast stations

New York City is the largest media market in the United States. Since the September 11, 2001 attacks, nearly all of the city's commercial broadcast stations (both television and FM radio) have transmitted from the top of the Empire State Building, although a few FM stations are located at the nearby Condé Nast Building. Most New York City AM stations broadcast from just across the Hudson River in New Jersey.

Broadcasting began at Empire on December 22, 1931, when RCA began transmitting experimental television broadcasts from a small antenna erected atop the spire. They leased the 85th floor and built a laboratory there, and—in 1934—RCA was joined by Edwin Howard Armstrong in a cooperative venture to test his FM system from the Empire antenna. When Armstrong and RCA fell out in 1935 and his FM equipment was removed, the 85th floor became the home of RCA's New York television operations, first as experimental station W2XBS channel 1, which eventually became (on July 1, 1941) commercial station WNBT, channel 1 (now WNBC-TV channel 4). NBC's FM station (WEAF-FM, now WQHT) began transmitting from the antenna in 1940. NBC retained exclusive use of the top of Empire until 1950, when the FCC ordered the exclusive deal broken, based on consumer complaints that a common location was necessary for the (now) seven New York television stations to transmit from so that receiving antennas would not have to be constantly adjusted. Construction on a giant tower began. Other television broadcasters then joined RCA at Empire, on the 83rd, 82nd, and 81st floors, frequently bringing sister FM stations along for the ride. Multiple transmissions of TV and FM began from the new tower in 1951. In 1965, a separate set of FM antennas was constructed ringing the 103rd floor observation area. When the World Trade Center was being constructed, it caused serious problems for the television stations, most of which then moved to the World Trade Center as soon as it was completed. This made it possible to renovate the antenna structure and the transmitter facilities for the benefit of the FM stations remaining there, which were soon joined by other FMs and UHF TVs moving in from elsewhere in the metropolitan area. The destruction of the World Trade Center necessitated a great deal of shuffling of antennas and transmitter rooms to accommodate the stations moving back uptown.

As of 2009, the Empire State Building is home to the following stations:

- TV: WCBS-TV 2, WNBC-TV 4, WNYW 5, WABC-TV 7, WWOR-TV 9 Secaucus, WPIX-TV 11, WNET 13 Newark, WNYE-TV 25, WPXN-TV 31, WXTV 41 Paterson, WNJU 47 Linden, and WFUT-TV 68 Newark

- FM: WXRK 92.3, WPAT-FM 93.1 Paterson, WNYC-FM 93.9, WPLJ 95.5, WXNY 96.3, WQHT-FM 97.1, WSKQ-FM 97.9, WRKS-FM 98.7, WBAI 99.5, WHTZ 100.3 Newark, WCBS-FM 101.1, WRXP 101.9, WWFS 102.7, WKTU 103.5 Lake Success, WAXQ 104.3, WWPR-FM 105.1, WQXR-FM 105.9 Newark, WLTW 106.7, and WBLS 107.5

Empire State Building Run-Up

The Empire State Building Run-Up is a foot race from ground level to the 86th-floor observation deck that has been held annually since 1978. Its participants are referred to both as runners and as climbers, and are often tower running enthusiasts. The race covers a vertical distance of 1,050 feet (320 m) and takes in 1,576 steps. The record time is 9 minutes and 33 seconds, achieved by Australian professional cyclist Paul Crake in 2003,[63][64] at a climbing rate of 6,593 ft (2,010 m) per hour.

In popular culture

- Film

- Perhaps the most famous popular culture representation of the building is in the 1933 film King Kong, in which the title character, a giant ape, climbs to the top to escape his captors but falls to his death after being attacked by airplanes. In 1983, for the 50th anniversary of the film, a huge 90 foot tall inflatable King Kong was placed on the building mast above the observation deck as a skyscraper sculpture by artist Robert Keith Vicino. In 2005, a remake of King Kong was released, set in 1930s New York City, including a final showdown between Kong and bi-planes atop a greatly detailed Empire State Building. (The 1976 remake of King Kong was set in a contemporary New York City and held its climactic scene on the towers of the World Trade Center.)

- The 1939 romantic drama film Love Affair involves a couple who plan to meet atop the Empire State Building, a rendezvous that is averted by an automobile accident. The film was remade in 1957 (as An Affair to Remember) and in 1994 (again as Love Affair). The 1993 film Sleepless in Seattle, a romantic comedy partially inspired by An Affair to Remember, climaxes with a scene at the Empire State observatory.

- Andy Warhol's 1964 silent film Empire is one continuous, eight-hour shot of the Empire State Building at night, shot in black-and-white. In 2004, the National Film Registry deemed its cultural significance worthy of preservation in the Library of Congress.

- The film Independence Day features the Empire State Building as the focal point for the aliens' attack on New York City. The building is destroyed in an extraordinary explosion by the aliens' primary weapon, which proceeds to destroy the entire city.

- Many other movies that feature the Empire State Building are listed on the building's own website.[65]

- In the film Knowing a massive solar flare incinerates the Earth. In the movie's destruction sequence of New York City, the Empire State Building can be seen crumbling as it is engulfed by the wall of flames.

- In the film When Worlds Collide, the Empire State Building is depicted as one of the few remaining buildings standing after New York City has flooded due to the passing of another planet.

- In the film The Day After Tomorrow, the Empire State Building can be seen freezing over during a superstorm that creates another ice age.

- In the film Aftershock: Earthquake in New York, the building fell and was destroyed by an earthquake hitting New York City.

- In the film Percy Jackson & the Olympians: The Lightning Thief, Mount Olympus is located over the Empire State Building, and there is a special elevator in the building to the "600th floor," which is supposed to be Olympus, just like in the book series.

- The building is chosen as Ground Zero for the target of a nuclear bomb that is dropped on New York in the film Fail-Safe.

- In the 2003 film Elf, Buddy the Elf's father works for a children's book publishing company located in the Empire State Building.

- Television

- The Empire State Building featured in the 1966 Doctor Who serial The Chase, in which the TARDIS lands on the roof of the building; The Doctor and his companions leave quite quickly, however, because The Daleks are close behind them. A Dalek is also seen on the roof of the building while it interrogates a human. In 2007, Doctor Who episodes "Daleks in Manhattan" and "Evolution of the Daleks" also featured the building, which the Daleks are constructing to use as a lightning conductor. Russell T Davies said in an article that "in his mind", the Daleks remembered the building from their last visit.

- In the Thunderbirds episode Terror In New York City, the Empire State Building crashes to the ground when an attempt to move it fails.

- The Discovery Channel show MythBusters tested the urban myth which claims that if one drops a penny off the top of the Empire State Building, it could kill someone or put a crater in the pavement. The outcome was that, by the time the penny hits the ground, it is going roughly 65 mph (105 km/h) (terminal velocity for an object of its mass and shape), which is not fast enough to inflict lethal injury or put a crater into the pavement. The urban legend is a joke in the 2003 musical Avenue Q, where a character waiting atop the building for a rendezvous tosses a penny over the side—only to hit her rival.

- The building is seen crumbling in the future without humans due to disintegration in the TV series Life After People.

- Literature

- H.G. Wells' 1933 science fiction book The Shape of Things to Come, written in the form of a history book published in the far future, includes the following passage: "Up to quite recently Lower New York has been the most old-fashioned city in the world, unique in its gloomy antiquity. The last of the ancient skyscrapers, the Empire State Building, is even now under demolition in C.E. 2106!".[66]

- In the science fiction novel The Rebel of Rhada by Robert Cham Gilman (Alfred Coppel), taking place at a decayed galactic empire of the far future, New York is an ancient city which was destroyed and rebuilt countless times. Its highest and most ancient building, covered with piled-up ruins up to half its height, is known simply as "The Empire Tower", but is obviously the Empire State Building.

- David Macaulay's 1980 illustrated book Unbuilding depicts the Empire State Building being purchased by a Middle Eastern billionaire and disassembled piece by piece, to be transported to Saudi Arabia and rebuilt there. The mooring mast is rebuilt in New York, while the remainder of the building is lost at sea.

- The Empire State Building is featured prominently as both a setting and integral plot device throughout much of Michael Chabon's 2000 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay.

- In the Percy Jackson book series, Mount Olympus is located over the Empire State Building, and there is a special elevator in the building to the "600th floor," which is supposed to be Olympus. In the last book of the series, the building plays a major role as the main characters' HQ. The building lights up in blue at the end of the book.

- Other

- A 7.6 feet (2.3 m) scale model built from 12,000 LEGO bricks over 250 hours is featured along with other notable buildings in the LEGO® Architecture: Towering Ambition exhibition at the National Building Museum in Washington , D.C.[67]

Notable tenants

|

|

Gallery

-

View from Weehawken

-

Empire State Building with red and green lights for Christmas, as seen from GE Building

-

Looking up

-

Looking down

-

Looking towards Times Square

-

Art deco elevators in the lobby

-

The Empire State Building lights up in yellow and red during the 60th anniversary of the PRC

-

In the distance at sunset

See also

- List of buildings with 100 floors or more

- List of tallest buildings in the world

- List of tallest buildings by U.S. state

- List of tallest freestanding structures in the world

- Skyscraper#History of tallest skyscrapers

References

- ^ The Empire State Building is located within the 10001 zip code area, but 10118 is assigned as the building's own zip code. Source: USPS.

- ^ National Geodetic Survey datasheet KU3602, Retrieved 2009-07-26

- ^ a b Willis, Carol (1995). "Empire State Building". In Kenneth T. Jackson (ed.). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven, CT & London & New York: Yale University Press & The New-York Historical Society. pp. 375–376.

- ^ ESBNYC.com

- ^ Pollak, Michael (April 23, 2006). "75 YEARS: F. Y. I." The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-31.

- ^ a b SkyscraperPage – Empire State Building, antenna height source: CTBUH, top floor & roof height source: Empire State Building Company LLC

- ^ a b Rosenberg, Jennifer. "Empire State Building Trivia and Cool Facts". About.com. Retrieved 2008-11-08.

- ^ a b "Empire State Building". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-11.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|work=at position 35 (help) Cite error: The named reference "nhlsum" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ a b White, Norval & Willensky, Elliot (2000). AIA Guide to New York City (4th ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-8129-3107-5. p.226.

- ^ Carolyn Pitts (April 26, 1985). "Empire State Building" (PDF). National Historic Landmark Nomination. National Park Service.

- ^ "Empire State Building—Accompanying 7 photos, exterior and interior, from 1978" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Inventory. National Park Service. 1985-04-26.

- ^ "W&H Properties – Empire State Building". Esbnycleasing.com. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ "2009 ULI Fall Meeting & Urban Land Expo - Green Retrofit: What Is Making This the Wave of the Future?" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ "Empire State Building : Official Internet Site". Esbnyc.com. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ Reynolds Building. Retrieved November 15, 2008.

- ^ "Cincinnati Skyscrapers, Waymarketing.com". Waymarking.com. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ "Thirteen Months to Go", Geraldine B. Wagner, 2003, Quintet Publishing Ltd., pg. 32

- ^ "New York". The Travelling Historian. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ "FINAL CURRICULUM" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ about.com – Empire State Building Trivia and Cool Facts

- ^ "Lewis Wickes Hine: The Construction of the Empire State Building, 1930–31 (New York Public Library Photography Collection)". Catalog.nypl.org. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

{{cite web}}: Text "P0%2C6" ignored (help); Text "Rb11970057" ignored (help); Text "SLewis+Wickes+Hine" ignored (help) - ^ "Tower Lights History". Empire State Building. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ^ "Robot Elevators To Serve 85,000 In Greatest Building", April 1931, Popular Science photos and drawings of original elevators layout

- ^ "Facts & Trivia". Empire State Building. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ Lelyveld, Joseph (February 23, 1964). "The Empire State to Glow at Night". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ Tallmer, Jerry (September 29, 2004). "Whatever happened to Fay Wray?". The Villager. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ a b "Lighting Schedule". Empire State Building. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ "The Tallest Buildings in the World". The Washington Post. January 4, 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ Schlabach, Mark (November 10, 2006). "Rutgers finds new level of success with win". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ Segal, David (August 24, 1995). "With Windows 95's Debut, Microsoft Scales Heights of Hype". The Washington Post. p. A14. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ "empirestate1.jpg | Columbia University Image Gallery". Gallery.columbia.edu. 2009-05-20. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ http://articles.latimes.com/1990-06-10/news/mn-146_1_empire-state-building

- ^ "German Missions in the United States - Home". Germany.info. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ "Empire State Building Goes Green for Muslim Holiday". Fox News. October 13, 2007. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ "Empire State adorns yellow to celebrate The Simpsons Movie". Businesswire.com. 2007-12-16. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ "Empire State's Vision of Love Is Mariah Carey in Lights". New York Times. 2008-04-25. Retrieved 2011-01-06.

- ^ Wicked - Broadway. "Empire State Building Goes Green for Wicked Birthday; Final Yellow Brick Road Cast Announced". Broadway.com. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ "El Empire State Building se viste con 'La Roja' | Estados Unidos". elmundo.es. 2010-07-13. Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ "NYT Travel: Empire State Building". Travel.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ Smith, Adam (August 18, 2008). "A Renters' Market in London". Time. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ [2]—New York: A Documentary Film.

- ^ a b Shanor, Rebecca Read (1995). "Unbuilt projects". In Kenneth T. Jackson (ed.). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven, CT & London & New York: Yale University Press & The New-York Historical Society. pp. 1208–1209.

- ^ "Dirigible To Try Mooring To Mooring Mast", May 1931, Popular Science drawing of mooring mast and dispute about it between US and German dirigible captains

- ^ Goldman, Jonathan (1980). The Empire State Building Book. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 44.

- ^ "Intercity Dirigible Service". 2010-02-26. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- ^ "750th Squadron 457th Bombardment Group: Officers – 1943 to 1945". Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ^ "Empire State Building Withstood Airplane Impact". Tms.org. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ "Plane Hits Building – Woman Survives 75-Story Fall". Elevator-world.com. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ "guinnessworldrecords.com". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2006-03-17. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ "The Day A Bomber Hit The Empire State Building". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

Eight months after the crash, the U.S. government offered money to families of the victims. Some accepted, but others initiated a lawsuit that resulted in landmark legislation. The Federal Tort Claims Act of 1946, for the first time, gave American citizens the right to sue the federal government.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Glanz, James; Lipton, Eric (September 8, 2002). "The Height of Ambition". The New York Times.

- ^ Carmody, Deirdre (1972-10-11). "11 Floors May Be Added to the Empire State". The New York Times.

- ^ iht.com

- ^ Compass American Guides: Manhattan, 4th Edition. Reavill, Gil and Zimmerman, Jean P. 160.

- ^ LIFE - Google Books. Books.google.com. 1947-05-12. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ George H. Douglas, ''Skyscrapers'', p. 173. Books.google.com. 1979-12-02. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ Geoffrey Broughton, ''Expressions'', p. 32. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2010-10-11.

- ^ The Empire State Building Book, Jonathan Goldman, St. Martin's Press, 1980, p.63

- ^ a b "ESB Tickets". Empire State Building. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ "Ten Things Not to Do in New York". Concierge.com. Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ "NYRR Empire State Building Run-Up Crowns Dold and Walsham as Champions". New York Road Runners. February 6, 2007. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ "Past Race Winners". Empire State Building. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ "ESB in the Movies". Empire State Building. Retrieved 2010-12-07.

- ^ "The Shape Of Things To Come". Gutenberg.net.au. Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ "National Building Museum. LEGO® Architecture: Towering Ambition". Nbm.org. Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Foreigners flocking to 350 Fifth Avenue." Real Estate Weekly. June 30, 2004.

- ^ "FAQ." Alitalia (United States website). Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ "Claims and Suggestions." Alitalia (United States website). Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ Home page. Croatian National Tourist Board. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ "Contact." Filipino Reporter. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ "Contact." Human Rights Watch. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ Home Page. Polish Cultural Institute in New York. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ Information Senegal Tourist Office. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ "Travel Agencies for plane tickets to Romania." Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ "The King's College". Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ "Contact Us." China National Tourist Office. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ "Contact us." National Film Board of Canada. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ In Answer to Ayn Rand by Nathaniel Branden at his ex-wife's website

Further reading

- Aaseng, Nathan. (1999). Construction: Building the Impossible. Minneapolis, MN: Oliver Press. ISBN 1-881508-59-5.

- Bascomb, Neal. (2003). Higher: A Historic Race to the Sky and the Making of a City. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-50660-0.

- Goldman, Jonathan. (1980). The Empire State Building Book. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-24455-X.

- James, Theodore, Jr. (1975). The Empire State Building. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-012172-6.

- Kingwell, Mark. (2006). Nearest Thing to Heaven: The Empire State Building and American Dreams. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10622-X.

- Pacelle, Mitchell. (2001). Empire: A Tale of Obsession, Betrayal, and the Battle for an American Icon. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-40394-6.

- Tauranac, John. (1995). The Empire State Building: The Making of a Landmark. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-19678-6.

- Wagner, Geraldine B. (2003). Thirteen Months to Go: The Creation of the Empire State Building. San Diego, CA: Thunder Bay Press. ISBN 1-59223-105-5.

- Willis, Carol (ed). (1998). Building the Empire State. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-73030-1.

External links

- Empire State Building official Web site

- Film footage of the construction of the Empire State Building, 1930

- Commercial Construction.com

- Lighting Schedule

- Empire State Building Green Retrofit

- Empire State Building Trivia

- Empire State Building Information

- The Construction of the Empire State Building, 1930–1931, New York Public Library

- VIVA2 - Online archive of over 500 construction photographs

- NYC Insider Guide Visitor information.

- Empire State Building at Structurae

- Streetscapes: The Empire State Building - slideshow by The New York Times

- 1931 architecture

- Accidents involving fog

- Art Deco buildings in New York City

- Art Deco skyscrapers

- Buildings and structures on the National Register of Historic Places in Manhattan

- Family businesses

- Fifth Avenue (Manhattan)

- Former world's tallest buildings

- National Historic Landmarks in New York City

- Office buildings in Manhattan

- Office buildings in New York City

- Skyscrapers in New York City

- Skyscrapers over 350 meters

- Visitor attractions in New York City

- Visitor attractions in Manhattan