Migraine: Difference between revisions

ScottSteiner (talk | contribs) m Reverted unexplained removal of content (HG) |

m →Signs and symptoms: Added status migrainosus and link |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

==Signs and symptoms== |

==Signs and symptoms== |

||

Migraines typically present with recurrent severe [[headache]] associated with [[Autonomic nervous system|autonomic]] symptoms.<ref name=Bart10/> An [[Aura (symptom)|aura]] only occurs in a small percentage of people.<ref name=Bart10/> The severity of the pain, duration of the headache, and frequency of attacks is variable.<ref name=Bart10/> |

Migraines typically present with recurrent severe [[headache]] associated with [[Autonomic nervous system|autonomic]] symptoms.<ref name=Bart10/> An [[Aura (symptom)|aura]] only occurs in a small percentage of people.<ref name=Bart10/> The severity of the pain, duration of the headache, and frequency of attacks is variable.<ref name=Bart10/> A migraine lasting 72 hours is termed [[status migrainosus]] and can be treated with intravenous [[prochlorperazine]]. |

||

There are four possible phases to a migraine attack.<ref name="pmid14979299"/> They are listed below - not all the phases are necessarily experienced. Additionally, the phases experienced and the symptoms experienced during them can vary from one migraine attack to another in the same person: |

There are four possible phases to a migraine attack.<ref name="pmid14979299"/> They are listed below - not all the phases are necessarily experienced. Additionally, the phases experienced and the symptoms experienced during them can vary from one migraine attack to another in the same person: |

||

Revision as of 16:01, 17 April 2011

| Migraine | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Frequency | 12.6% |

Migraine (from the Greek words hemi, meaning half, and kranion, meaning skull[1]) is a debilitating condition characterized by moderate to severe headaches, and nausea. It is about three times more common in women than in men.[2]

The typical migraine headache is unilateral pain (affecting one half of the head) and pulsating in nature and lasting from 4 to 72 hours; symptoms include nausea, vomiting, photophobia (increased sensitivity to light), phonophobia (increased sensitivity to sound); the symptoms are generally aggravated by routine activity.[3][4] Approximately one-third of people who suffer from migraine headaches perceive an aura—unusual visual, olfactory, or other sensory experiences that are a sign that the migraine will soon occur.[5]

Initial treatment is with analgesics for the headache, an antiemetic for the nausea, and the avoidance of triggering conditions. The cause of migraine headache is unknown; the most common theory is a disorder of the serotonergic control system.[citation needed]

Studies of twins indicate a 60- to 65-percent genetic influence upon their propensity to develop migraine headaches.[6][7] Moreover, fluctuating hormone levels indicate a migraine relation: 75 percent of adult patients are women, although migraine affects approximately equal numbers of prepubescent boys and girls; propensity to migraine headache is known to disappear during pregnancy, although in some women migraines may become more frequent during pregnancy.[8]

Classification

The International Headache Society (IHS) offers guidelines for the classification and diagnosis of migraine headaches, in a document called "The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition" (ICHD-2).[3] These guidelines constitute arbitrary definitions, and are not supported by scientific data.[3]

According to ICHD-2, there are seven subclasses of migraines (some of which include further subdivisions):

- Migraine without aura, or common migraine, involves migraine headaches that are not accompanied by an aura (visual disturbance, see below).

- Migraine with aura usually involves migraine headaches accompanied by an aura. Less commonly, an aura can occur without a headache, or with a non-migraine headache. Two other varieties are Familial hemiplegic migraine and Sporadic hemiplegic migraine, in which a patient has migraines with aura and with accompanying motor weakness. If a close relative has had the same condition, it is called "familial", otherwise it is called "sporadic". Another variety is basilar-type migraine, where a headache and aura are accompanied by difficulty speaking, vertigo, ringing in ears, or a number of other brainstem-related symptoms, but not motor weakness.

- Childhood periodic syndromes that are commonly precursors of migraine include cyclical vomiting (occasional intense periods of vomiting), abdominal migraine (abdominal pain, usually accompanied by nausea), and benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood (occasional attacks of vertigo).

- Retinal migraine involves migraine headaches accompanied by visual disturbances or even temporary blindness in one eye.

- Complications of migraine describe migraine headaches and/or auras that are unusually long or unusually frequent, or associated with a seizure or brain lesion.

- Probable migraine describes conditions that have some characteristics of migraines but where there is not enough evidence to diagnose it as a migraine with certainty (in the prescence of concurrent medication overuse).

- Chronic migraine, according to the American Headache Society[9] and the international headache society,[10] is a "complication of migraine"s and is a headache fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for "migraine headache", which occurs for a greater time interval. Specifically, greater or equal to 15 days/month for greater than 3 months.

Signs and symptoms

Migraines typically present with recurrent severe headache associated with autonomic symptoms.[11] An aura only occurs in a small percentage of people.[11] The severity of the pain, duration of the headache, and frequency of attacks is variable.[11] A migraine lasting 72 hours is termed status migrainosus and can be treated with intravenous prochlorperazine.

There are four possible phases to a migraine attack.[3] They are listed below - not all the phases are necessarily experienced. Additionally, the phases experienced and the symptoms experienced during them can vary from one migraine attack to another in the same person:

- The prodrome, which occurs hours or days before the headache.

- The aura, which immediately precedes the headache.

- The pain phase, also known as headache phase.

- The postdrome.

Prodrome

Prodromal symptoms occur in 40–60% of those with migraines. This phase may consist of altered mood, irritability, depression or euphoria, fatigue, yawning, excessive sleepiness, craving for certain food (e.g. chocolate), stiff muscles (especially in the neck), hot ears, constipation or diarrhea, increased urination, and other visceral symptoms.[12] These symptoms usually precede the headache phase of the migraine attack by several hours or days, and experience teaches the patient or observant family how to detect that a migraine attack is near.

Aura

For the 20–30%[14][15] of migraine sufferers who experience migraine with aura, this aura comprises focal neurological phenomena that precede or accompany the attack. They appear gradually over 5 to 20 minutes and generally last fewer than 60 minutes. The headache phase of the migraine attack usually begins within 60 minutes of the end of the aura phase, but it is sometimes delayed up to several hours, and it can be missing entirely (see silent migraine). The pain may also begin before the aura has completely subsided. Symptoms of migraine aura can be sensory or motor in nature.[16]

Visual aura is the most common of the neurological events and can occur without any headache. There is a disturbance of vision consisting often of unformed flashes of white and/or black or rarely of multicolored lights (photopsia) or formations of dazzling zigzag lines (scintillating scotoma; often arranged like the battlements of a castle, hence the alternative terms "fortification spectra" or "teichopsia"[17]). Some patients complain of blurred or shimmering or cloudy vision, as though they were looking through thick or smoked glass, or, in some cases, tunnel vision and hemianopsia. For those suffering from this the prodrome is a small blurred spot that we cannot focus on. This is followed by a growing into a larger object such as a three sided square with the zig-zag line interfering with vision. This grows to a maximum size and then starts moving slowly through the field of vision until it exits the field of view. For all practical purposes the aura phase has then ended even if brain activity could be detected that would indicate an active aura.

The somatosensory aura of migraine may consist of digitolingual or cheiro-oral paresthesias, a feeling of pins-and-needles experienced in the hand and arm as well as in the nose-mouth area on the same side. The paresthesia may migrate up the arm and then extend to involve the face, lips and tongue.

Other symptoms of the aura phase can include auditory, gustatory or olfactory hallucinations, temporary dysphasia, vertigo, tingling or numbness of the face and extremities, and hypersensitivity to touch.

Oliver Sacks's book Migraine describes "migrainous deliria" as a result of such intense migraine aura that it is indistinguishable from "free-wheeling states of hallucinosis, illusion, or dreaming."

- Visual symptoms of migraine aura

-

Enhancements reminiscent of a zigzag fort structure

-

Negative scotoma, loss of awareness of local structures

-

Positive scotoma, local perception of additional structures

-

Mostly one-sided loss of perception

Pain

The typical migraine headache is unilateral, throbbing, and moderate to severe and can be aggravated by physical activity.[3] Not all these features are necessary. The pain may be bilateral at the onset or start on one side and become generalized, and may occur primarily on one side or alternate sides from one attack to the next. The onset is usually gradual. The pain peaks and then subsides and usually lasts 4 to 72 hours in adults and 1 to 48 hours in children. The frequency of attacks is extremely variable, from a few in a lifetime to several a week, and the average sufferer experiences one to three headaches a month. The head pain varies greatly in intensity.

The pain of migraine is invariably accompanied by other features. Nausea occurs in almost 90 percent of patients, and vomiting occurs in about one third of patients. Many patients experience sensory hyperexcitability manifested by photophobia, phonophobia, and osmophobia and seek a dark and quiet room. Blurred vision, delirium, nasal stuffiness, diarrhea, tinnitus, polyuria, pallor, or sweating may be noted during the headache phase. There may be localized edema of the scalp or face, scalp tenderness, prominence of a vein or artery in the temple, or stiffness and tenderness of the neck. Impairment of concentration and mood are common. The extremities tend to feel cold and moist. Vertigo may be experienced; a variation of the typical migraine, called vestibular migraine, has also been described. Lightheadedness, rather than true vertigo,[citation needed] and a feeling of faintness may occur.

Postdrome

The effects of migraine may persist for some days after the main headache has ended. Many sufferers report a sore feeling in the area where the migraine was, and some report impaired thinking for a few days after the headache has passed. The patient may feel tired or "hungover" and have head pain, cognitive difficulties, gastrointestinal symptoms, mood changes, and weakness.[18] According to one summary, "Some people feel unusually refreshed or euphoric after an attack, whereas others note depression and malaise."[19]

Cause

The cause of migraines is unknown.[20]

Triggers

A minority of migraines may be induced by triggers.[11] While many things have been labeled as triggers, the strength and significance of these relationships are uncertain.[21][22] The most common triggers quoted are stress, hunger, and fatigue; however, these equally contribute to tension headaches.[21] A 2003 review concluded that there was no scientific evidence for an effect of tyramine on migraine.[23] A 2005 literature review found that the available information about dietary trigger relies mostly on subjective assessments.[24] This is in line with other reviews. A 2009 review found little evidence to corroborate the environmental triggers reported.[25] While monosodium glutamate (MSG) is frequently reported as a dietary trigger[26] evidence does not consistently support this.[27]

Depolarization

It has been theorized that the phenomenon known as cortical spreading depression, which is associated with the aura of migraine,[28] can cause migraines. In cortical spreading depression, neurological activity is initially activated, then depressed over an area of the cortex of the brain. It has been suggested that situation results in the release of inflammatory mediators leading to irritation of cranial nerve roots, most particularly the trigeminal nerve, which conveys the sensory information for the face and much of the head. This theory is however speculative, without any supporting evidence, and there are indeed cogent arguments against it. First, only about one third of migraineurs experience an aura, and those who do not experience aura do not have cortical spreading depression.[citation needed] Second, many migraineurs have a prodrome (see above), which occurs up to three days before the aura.[12]

Vascular

Studies have shown that the aura coincides with constriction of blood vessels in the brain. This may start in the occipital lobe, in the back of the brain, as arteries spasm. The reduced flow of blood from the occipital lobe triggers the aura that some individuals who have migraines experience because the visual cortex is in the occipital area.[29][unreliable source?]

When the constriction of blood vessels in the brain stops and the aura subsides, the blood vessels of the scalp dilate.[30] The walls of these blood vessels become permeable and some fluid leaks out. This leakage is recognized by pain receptors in the blood vessels of surrounding tissue. In response, the body supplies the area with chemicals which cause inflammation. With each heart beat, blood passes through this sensitive area causing a throb of pain.[29][unreliable source?]

Serotonin

Serotonin is a type of neurotransmitter, or "communication chemical" which passes messages between nerve cells. It helps to control mood, pain sensation, sexual behaviour, sleep, as well as dilation and constriction of the blood vessels among other things. Low serotonin levels in the brain may lead to a process of constriction and dilation of the blood vessels which trigger a migraine.[29] Serotonergic agonists like triptans,[29] LSD or psilocin activate serotonin receptors to stop a migraine attack.

Melanopsin receptor

A melanopsin-based receptor has been linked to the association between light sensitivity and migraine pain,[31] but this is at this stage speculation.

Neural

When certain nerves or an area in the brain stem become irritated, a migraine begins. In response to the irritation, the body releases chemicals which cause inflammation of the blood vessels. These chemicals cause further irritation of the nerves and blood vessels and results in pain. Substance P is one of the substances released with first irritation. Pain then increases because substance P aids in sending pain signals to the brain.[29]

Unifying theory

Both vascular and neural influences cause migraines.

- stress triggers changes in the brain

- these changes cause serotonin to be released

- blood vessels constrict and dilate

- chemicals including substance P irritate nerves and blood vessels causing neurogenic inflammation and pain[29]

Pathophysiology

Migraine is a neurovascular disorder.[11] Although migraine is thought by some to be a neurological disease, in the absence of scientific evidence, this remains a hypothesis.

Initiation

Migraines were once thought to be initiated exclusively by problems with blood vessels, but the vascular changes of migraines are now considered by some to be secondary to brain dysfunction,[29] although this concept has not been supported by the evidence. This was eloquently summed up by Dodick who wrote ‘There is no disputing the role of the central nervous system in the susceptibility, modulation and expression of migraine headache and the associated affective, cognitive, sensory, and neurological symptoms and signs. However to presume that migraine is always generated from within the central nervous system, based on the available evidence, is naïve at best and unscientific at worst.The emerging evidence would suggest that just as alterations in neuronal activity can lead to downstream effects on the cerebral blood vessel, so too can changes within endothelial cells or vascular smooth muscle lead to downstream alterations in neuronal activity. Therefore, there are likely patients, and/or at least attacks in certain patients, where primarily vascular mechanisms predominate.'[32] Some have even attempted to show that vascular changes are of no importance in migraine,[33] [34] but this claim is unsubstantiated and has not been supported by scientific evidence. 'If we swing between vascular and neurogenic views of migraine, it is probably because both vascular and neurogenic mechanisms for migraine exist and are important'- J Edmeads[35]

Pain

Although the initiating factor of migraine remains unknown, there is a great deal of irrefutable evidence to show that the pain of migraine (the third phase)[3] is in some patients related to painful dilatation of the terminal branches of the external carotid artery, and in particular its superficial temporal and occipital branches.[30][36][37][38][39][40] It was previously thought that dilatation of the arteries in the brain and dura mater was the origin of the vascular pain, but it has now been shown that these vessels do not dilate during migraine.[41][42] Because these arteries are relatively superficial, it is easy to diagnose whether they are the source of the pain. If they are, then they are also accessible to a form of migraine surgery that is being promoted, largely to the efforts of Dr Elliot Shevel, a South African surgeon, who has reported excellent success using the procedure.[43]

Pericranial (jaw and neck) muscle tenderness is a common finding in migraine[44][45][46] It has actually been shown that muscle tenderness is present in 100% of migraine attacks, so muscle tenderness is the single most common finding in migraine.[47] Tender muscle trigger points can be at least part of the cause, and perpetuate most kinds of headaches.[48][unreliable source?]

Diagnosis

Migraines are underdiagnosed[49] and often misdiagnosed.[50] The diagnosis of migraine without aura, according to the International Headache Society, can be made according to the following criteria, the "5, 4, 3, 2, 1 criteria":[51]

- 5 or more attacks. For migraine with aura, only two attacks are sufficient for diagnosis.

- 4 hours to 3 days in duration.

- 2 or more of the following:

- Unilateral (affecting half the head);

- Pulsating;

- "Moderate or severe pain intensity";

- "Aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity".

- 1 or more of the following:

- "Nausea and/or vomiting";

- Sensitivity to both light (photophobia) and sound (phonophobia).

The mnemonic POUNDing (Pulsating, duration of 4–72 hOurs, Unilateral, Nausea, Disabling) can help diagnose migraine. If 4 of the 5 criteria are met, then the positive likelihood ratio for diagnosing migraine is 24.[52]

The presence of either disability, nausea or sensitivity, can diagnose migraine with:[53]

- sensitivity of 81%

- specificity of 75%

Migraine should be differentiated from other causes of headaches such as cluster headaches. These are extremely painful, unilateral headaches of a piercing quality. The duration of the common attack is 15 minutes to three hours. Onset of an attack is rapid, and most often without the preliminary signs that are characteristic of a migraine.[citation needed]

Medical imaging of the head and neck may be used to rule out secondary causes of headaches.[11]

Prevention

Preventive (also called prophylactic) treatment of migraines can be an important component of migraine management. Such treatments can take many forms, including taking preventive drugs, migraine surgery, taking nutritional supplements, lifestyle alterations such as increased exercise, and avoidance of migraine triggers, .

The goals of preventive therapy are to reduce the frequency, painfulness, and/or duration of migraines, and to increase the effectiveness of abortive therapy.[54] Another reason to pursue these goals is to avoid medication overuse headache (MOH), otherwise known as rebound headache. This is a common problem among migraneurs, and can result in chronic daily headache.[55][56]

Many of the preventive treatments are quite effective. Even with a placebo, one-quarter of patients find that their migraine frequency is reduced by half or more, and actual treatments often far exceed this figure.[57]

Medication

Preventive migraine drugs are considered effective if they reduce the frequency or severity of migraine attacks by 50%.[58] The major problem with migraine preventive drugs, apart from their relative inefficiency, is that unpleasant side effects are common. For this reason, preventive medication is limited to patients with frequent or severe headaches.[59]

There are many medicines available to prevent or reduce frequency, duration and severity of migraine attacks. They may also prevent complications of migraine. Beta blockers such as Propranolol, atenolol, and metoprolol, calcium channel blockers such as amlodipine, flunarizine and verapamil, the anticonvulsants sodium valproate, divalproex gabapentin and topiramate and tricyclic antidepressants are some of the commonly used drugs.

Tricyclics have been found to be more effective than SSRIs.[60] Tricyclic antidepressants have been long established as efficacious prophylactic treatments.[58] These drugs, however, may give rise to undesirable side effects, such as insomnia, sedation or sexual dysfunction. There is no consistent evidence that SSRI antidepressants are effective for migraine prophylaxis. While amitryptiline (Elavil) is the only tricyclic to have received FDA approval for migraine treatment, other tricyclic antidepressants are believed to act similarly and are widely prescribed, often to find one with a profile of side-effects that is acceptable to the patient.[58] In addition to tricyclics a, the anti-depressant nefazodone may also be beneficial in the prophylaxis of migraines due to its antagonistic effects on the 5-HT2A[61] and 5-HT2C receptors[62][63] It has a more favorable side effect profile than amitriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant commonly used for migraine prophylaxis. Anti-depressants offer advantages for treating migraine patients with comorbid depression.[58] Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of migraines, but have been found to be effective by some practitioners.[58]

There is some evidence that low-dose asprin has benefit for reducing the occurrence of migraines in susceptible individuals.[64][65][66][67]

Surgery

Migraine surgery is a field that shows a great deal of promise, particularly in those who suffer more frequent attacks, and in those who have not had an adequate response to prophylactic medications. Patients often still experience a poor quality of life despite an aggressive regimen of pharmacotherapy.[68] For these reasons, surgical solutions to migraines have been developed, which have excellent results.[69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81] A major advantage of migraine surgery, is that with the correct diagnostic techniques, a definite diagnosis can be made before the surgery is undertaken. Once a positive diagnosis has been made, the results of surgery are outstanding and provides permanent pain relief, as well as relief from the associated symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, light sensitivity, and sound sensitivity. Surgical cauterization of the superficial blood vessels of the scalp (the terminal branches of the external carotid artery) is only carried out if the clinical examination has shown that these vessels are indeed a source of pain. It is a safe and relatively atraumatic procedure that can be performed in a day facility.[82] The value of arterial sugery for migraine treatment is gaining recognition due to the efforts of a South African surgeon, Dr Elliot Shevel, who has produced a number of papers on the subject.

The removal of muscles or nerves in areas known as "trigger sites" provides good results, but only in patients who respond well to Botox injections in specific areas.[70]

There is also evidence that the correction of a congenital heart defect, patent foramen ovale (PFO), reduces migraine frequency and severity.[83] Recent studies have advised caution though in relation to PFO closure for migraines, as insufficient evidence exists to justify this dangerous procedure.[84][85]

Other therapies

A systematic review stated that chiropractic manipulation, physiotherapy, massage and relaxation might be as effective as propranolol or topiramate in the prevention of migraine headaches, however the research had some problems with methodology.[86]

Migraine diary

Keeping a migraine diary may make it possible to identify food triggers, and therefore help to avoid them.[11] Controlling the intake of foods such as hot dogs, chocolate, cheese and ice cream - the list is endless - could help alleviate symptoms.[87] A trigger may occur up to 24 hours prior to the onset of symptoms.[11] The majority of migraines are not however caused by identifiable triggers.[11]

Management

There are three main aspects of treatment: trigger avoidance, acute symptomatic control, and pharmacological prevention.[11] Medications are more effective if used earlier in an attack.[11] The frequent use of medications may however result in medication overuse headache (MOH), in which the headaches become more severe and more frequent. These may occur with triptans, ergotamines, and analgesics, especially narcotics analgesics.[3]

Analgesics

A number of analgesics are effective for treating migraines including:

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Ibuprofen provides pain effective pain relief in about half of people.[88] Naproxen can abort about one third of migraine attacks, which was 5% less than the benefit of sumatriptan.[89] A 1000 mg dose of Aspirin (also called ASA) could relieve moderate to severe migraine pain, with similar effectiveness to sumatriptan.[90]

- Paracetamol/acetaminophen either alone or in combination with metaclopramide is effective for migraines.[91]

- Simple analgesics combined with caffeine may help.[92] Even by itself, caffeine can be useful during an attack,[93][94] despite the fact that in general migraine-sufferers are advised to limit their caffeine intake.[94]

Triptans

Triptans such as sumatriptan are effective for both pain and nausea in up to 75% of people.[11][95] They come in a number of different forms including oral, injection, nasal spray, and oral dissolving tablets.[11] Most side effects are mild such as flushing however rare cases of myocardial ischemia have occurred.[11] They are non addictive, but may cause medication overuse headaches if used more than 10 days per month.[96]

Ergotamines

Dihydroergotamine is an older medication that some find useful.[11] They were the primary oral drugs available to abort a migraine prior to the triptans. They are much less expensive than triptans and continues to be prescribed for migraines.

Corticosteroids

A single dose of intravenous dexamethasone, when added to standard treatment of a migraine attack, is associated with a 26% decrease in headache recurrence in the following 72 hours.[97]

Other

Antiemetics by mouth may help relieve symptoms of nausea and help prevent vomiting, which can diminish the effectiveness of orally taken analgesia. In addition some antiemetics such as metoclopramide are prokinetics and help gastric emptying which is often impaired during episodes of migraine. In the UK, there are three combination antiemetic and analgesic preparations available: MigraMax (aspirin with metoclopramide), (paracetamol/codeine for analgesia, with buclizine as the antiemetic) and paracetamol/metoclopramide (Paramax in UK).[98] The earlier these drugs are taken in the attack, the better their effect.

Prognosis

The risk of stroke may be increased two- to threefold in migraine sufferers. Young adult sufferers and women using hormonal contraception appear to be at particular risk.[99] The mechanism of any association is unclear, but chronic abnormalities of cerebral blood vessel tone may be involved. Women who experience auras have been found to have twice the risk of strokes and heart attacks over non-aura migraine sufferers and women who do not have migraines.[99][100] (Note: Women who experience auras and also take oral contraceptives have an even higher risk of stroke).[101] Migraine sufferers seem to be at risk for both thrombotic and hemorrhagic stroke as well as transient ischemic attacks.[102] Death from cardiovascular causes was higher in people with migraine with aura in a Women's Health Initiative study, but more research is needed to confirm this.[100][103]

Epidemiology

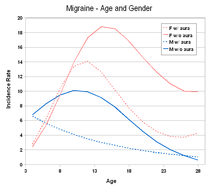

Worldwide migraines affect more than 10% of people.[20] In the United States approximately 6% of men and 18% of women get a migraine in a given year with a lifetime risk of about 18% and 43% respectively.[11] In Europe migraines affect 12–28% of people at some point in their lives.[2] Based on the results of a number of studies, one year prevalence of migraine ranges from 6–15% in adult men and from 14–35% in adult women.[2] These figures vary substantially with age: approximately 4–5% of children aged under 12 suffer from migraine, with little apparent difference between boys and girls.[104] There is then a rapid growth in incidence amongst girls occurring after puberty,[105][106][107] which continues throughout early adult life.[108] By early middle age, around 25% of women experience a migraine at least once a year, compared with fewer than 10% of men.[2][109] After menopause, attacks in women tend to decline dramatically, so that in the over 70s there are approximately equal numbers of male and female sufferers, with prevalence returning to around 5%.[2][109]

At all ages, migraine without aura is more common than migraine with aura, with a ratio of between 1.5:1 and 2:1.[110][111] Incidence figures show that the excess of migraine seen in women of reproductive age is mainly due to migraine without aura.[110] Thus in pre-pubertal and post-menopausal populations, migraine with aura is somewhat more common than amongst 15–50 year olds.[108][112]

There is a strong relationship between age, sex and type of migraine.[113]

Studies in Asia and South America suggest that the rates there are relatively low,[114][115] but they do not fall outside the range of values seen in European and North American studies.[2][109]

The incidence of migraine is related to the incidence of epilepsy in families, with migraine twice as prevalent in family members of epilepsy sufferers, and more common in epilepsy sufferers themselves.[116]

History

Trepanation, the deliberate and (usually) non-fatal drilling of holes into a skull, was practiced 9,000 years ago and earlier.[117] Some scholars have (controversially) speculated that this drastic procedure might have been a migraine treatment, based on cave paintings[118] and on the fact that trepanation was a historical migraine treatment in 17th-century Europe.[117][119] An early written description consistent with migraines is contained in the Ebers papyrus, written around 1200 BC in ancient Egypt.[117]

In 400 BC Hippocrates described the visual aura that can precede the migraine headache and the relief which can occur through vomiting. Aretaeus of Cappadocia is credited as the "discoverer" of migraines because of his second century description of the symptoms of a unilateral headache associated with vomiting, with headache-free intervals in between attacks.

Galenus of Pergamon used the term "hemicrania" (half-head), from which the word "migraine" was derived. He thought there was a connection between the stomach and the brain because of the nausea and vomiting that often accompany an attack. For relief of migraine, Andalusian-born physician Abulcasis, also known as Abu El Qasim, suggested application of a hot iron to the head or insertion of garlic into an incision made in the temple.

In the Middle Ages migraine was recognized as a discrete medical disorder with treatment ranging from hot irons to bloodletting and even witchcraft[citation needed]. Followers of Galenus explained migraine as caused by aggressive yellow bile. Ebn Sina (Avicenna) described migraine in his textbook "El Qanoon fel teb" as "... small movements, drinking and eating, and sounds provoke the pain... the patient cannot tolerate the sound of speaking and light. He would like to rest in darkness alone." Abu Bakr Mohamed Ibn Zakariya Râzi noted the association of headache with different events in the lives of women, "...And such a headache may be observed after delivery and abortion or during menopause and dysmenorrhea."

In Bibliotheca Anatomica, Medic, Chirurgica, published in London in 1712, five major types of headaches are described, including the "Megrim", recognizable as classic migraine. The term "Classic migraine" is no longer used, and has been replaced by the term "Migraine with aura"[3] Graham and Wolff (1938) published their paper advocating ergotamine tartrate for relieving migraine. Later in the 20th century, Harold Wolff (1950) developed the experimental approach to the study of headache and elaborated the vascular theory of migraine, which has come under attack as the pendulum again swings to the neurogenic theory. Recently however, there has been renewed interest in Wolff's vascular theory of migraine led by Elliot Shevel, a South African headache specialist, who has published a number of articles providing compelling evidence that Wolff was in fact correct.[43][120][121][37]

Society and culture

Economic impact

Chronic migraine attacks are a significant source of both medical costs and lost productivity. It has been estimated to be the most costly neurological disorder in the European Community, costing more than €27 billion per year.[122] Medical costs per migraine sufferer (mostly physician and emergency room visits) averaged $107 USD over six months in one 1988 study,[citation needed] with total costs including lost productivity averaging $313. Annual employer cost of lost productivity due to migraines was estimated at $3,309 per sufferer. Total medical costs associated with migraines in the United States amounted to one billion dollars in 1994, in addition to lost productivity estimated at thirteen to seventeen billion dollars per year. Employers may benefit from educating themselves on the effects of migraines in order to facilitate a better understanding in the workplace. The workplace model of 9–5, 5 days a week may not be viable for a migraine sufferer. With education and understanding an employer could compromise with an employee to create a workable solution for both.[citation needed]

Research

Merck Corp is developing a new drug called Telcagepant which is intended to relieve pain without causing vasoconstriction (narrowing of blood vessels) as current medications such as triptans do. Telcagepant would be a safe therapy for migraine suffers with risk factors for cardiovascular disease.[123]

Recently it has been found that calcitonin gene related peptides (CGRPs) play a role in the pathogenesis of the pain associated with migraine as triptans also decrease its release and action. CGRP receptor antagonists such as olcegepant and telcagepant are being investigated both in vitro and in clinical studies for the treatment of migraine.[124]

In 2010, scientists identified a genetic defect linked to migraines which could provide a target for new drug treatments.[125]

References

- ^ Mosby’s Medical, Nursing and Allied Health Dictionary, Fourth Edition, Mosby-Year Book 1994, p. 998

- ^ a b c d e f Stovner LJ, Zwart JA, Hagen K, Terwindt GM, Pascual J (2006). "Epidemiology of headache in Europe". European Journal of Neurology. 13 (4): 333–45. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01184.x. PMID 16643310.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (2004). "The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition". Cephalalgia. 24 Suppl 1: 9–160. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00653.x. PMID 14979299.

- ^ "NINDS Migraine Information Page". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ^ "Guidelines for all healthcare professionals in the diagnosis and management of migraine, tension-type, cluster and medication-overuse headache, January 2007, British Association for the Study of Headache" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ^ Gervil M, Ulrich V, Kaprio J, Olesen J, Russell MB (1999). "The relative role of genetic and environmental factors in migraine without aura". Neurology. 53 (5): 995–9. PMID 10496258.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ulrich V, Gervil M, Kyvik KO, Olesen J, Russell MB (1999). "The inheritance of migraine with aura estimated by means of structural equation modelling". Journal of Medical Genetics. 36 (3): 225–7. PMC 1734315. PMID 10204850.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lay CL, Broner SW (2009). "Migraine in women". Neurologic Clinics. 27 (2): 503–11. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2009.01.002. PMID 19289228.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.americanheadachesociety.org/

- ^ http://www.ihs-classification.org/en/

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Bartleson JD, Cutrer FM (2010). "Migraine update. Diagnosis and treatment". Minn Med. 93 (5): 36–41. PMID 20572569.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Kelman L (2004). "The premonitory symptoms (prodrome): a tertiary care study of 893 migraineurs". Headache. 44 (9): 865–72. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04168.x. PMID 15447695.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ [1] Dahlem MA, Engelmann R, Löwel S, Müller SC.,Does the migraine aura reflect cortical organization? Eur J Neurosci. 12:767-70, 2000.

- ^ Silberstein, Stephen D. (2005). Atlas Of Migraine And Other Headaches. London: Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 1-84214-273-9.[page needed]

- ^ Mathew, Ninan T.; Evans, Randolph W. (2005). Handbook of headache. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-5223-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)[page needed] - ^ Silberstein, Stephen D. (2002). Headache in Clinical Practice (2nd ed.). London: Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 1-901865-88-6.[page needed]

- ^ "Teichopsia - Medical Dictionary Definition", Stedman's Medical Dictionary, Retrieved on 2010-03-15.

- ^ Kelman L (2006). "The postdrome of the acute migraine attack". Cephalalgia. 26 (2): 214–20. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01026.x. PMID 16426278.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Audrey L. Halpern, MD and Stephen D. Silberstein, MD, "The Migraine Attack—A Clinical Description", in Chapter 9 of Imitators of Epilepsy, weblink.

- ^ a b Robbins MS, Lipton RB (2010). "The epidemiology of primary headache disorders". Semin Neurol. 30 (2): 107–19. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1249220. PMID 20352581.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Levy D, Strassman AM, Burstein R (2009). "A critical view on the role of migraine triggers in the genesis of migraine pain". Headache. 49 (6): 953–7. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01444.x. PMID 19545256.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Martin PR (2010). "Behavioral management of migraine headache triggers: learning to cope with triggers". Curr Pain Headache Rep. 14 (3): 221–7. doi:10.1007/s11916-010-0112-z. PMID 20425190.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Jansen SC, van Dusseldorp M, Bottema KC, Dubois AE (2003). "Intolerance to dietary biogenic amines: a review". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 91 (3): 233–40, quiz 241–2, 296. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63523-5. PMID 14533654.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Holzhammer J, Wöber C (2006). "[Alimentary trigger factors that provoke migraine and tension-type headache]". Schmerz (in German). 20 (2): 151–9. doi:10.1007/s00482-005-0390-2. PMID 15806385.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Friedman DI, De ver Dye T (2009). "Migraine and the environment". Headache. 49 (6): 941–52. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01443.x. PMID 19545255.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sun-Edelstein C, Mauskop A (2009). "Foods and supplements in the management of migraine headaches". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 25 (5): 446–52. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31819a6f65. PMID 19454881.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Freeman M (2006). "Reconsidering the effects of monosodium glutamate: a literature review". J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 18 (10): 482–6. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00160.x. PMID 16999713.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lauritzen M (1994). "Pathophysiology of the migraine aura. The spreading depression theory". Brain. 117 (1): 199–210. doi:10.1093/brain/117.1.199. PMID 7908596.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Alexander Mauskop; Fox, Barry (2001). What Your Doctor May Not Tell You About(TM): Migraines : The Breakthrough Program That Can Help End Your Pain. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-67826-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)[page needed] - ^ a b Shevel E (2011). "The Extracranial Vascular Theory of Migraine – A Great Story Confirmed by the Facts". Headache. 51: 409–417.

- ^ Noseda R, Kainz V, Jakubowski M; et al. (2010). "A neural mechanism for exacerbation of headache by light". Nature Neuroscience. 13 (2): 239–45. doi:10.1038/nn.2475. PMC 2818758. PMID 20062053.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dodick DW (2008). "Examining the essence of migraine--is it the blood vessel or the brain? A debate". Headache. 48: 661–7. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01079.x. PMID 18377395.

- ^ Goadsby P (2009). "The vascular theory of migraine – a great story wrecked by the facts". Brain. 132 (2): 6, 7. doi:10.1093/brain/awn321. PMID 19098031.

- ^ Cohen AS, Goadsby PJ (2005). "Functional neuroimaging of primary headache disorders". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 9 (2): 141–6. doi:10.1007/s11916-005-0053-0. PMID 15745626.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dodick, DW (2008). "Examining the Essence of Migraine – Is it Blood Vessel or the Brain? A Debate". Headache. 48 (4): 661–667. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01079.x. PMID 18377395.

- ^ Shevel, Elliot (September 19, 2007). "The Role of the External Carotid Vasculature in Migraine". In Clarke, Laura B (ed.). Migraine Disorders Research Trends. New York, New York, US: Nova Science Publishers. pp. 165–183. ISBN 9781600215537. Template:Google books with page

- ^ a b Shevel E, Spierings E (2004). "Role of the Extracranial Arteries in Migraine Headache: a Review". Cranio:the Journal of Craniomandibular Practice. 22 (2): 132–6. PMID 15134413.

- ^ Wolff HG, Tunis MM, Goodell H. (1953). "Studies on headache; evidence of damage and changes in pain sensitivity in subjects with vascular headaches of the migraine type". Transactions of the Association of American Physicians. 66 (4): 332–341. PMID 13091465.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pickering GW (1939). "Experimental Observations on Headache". British Medical Journal. 1 (4–6): 907–912. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4087.907. PMC 2209487. PMID 13306341.

- ^ Tunis MM, Wolff HG. (1953). "Analysis of Arterial Pulse Waves in Patients with Vascular Headache of the Migraine Type". American Journal of Medical Science. 224 (5): 121–123. PMID 12985578.

- ^ Schoonman GG, van der Grond J, Kortmann C, van der Geest RJ, Terwindt GM, Ferrari MD. (2008). "Migraine headache is not associated with cerebral or meningeal vasodilatation--a 3T magnetic resonance angiography study". Brain. 131: 2192–2200. PMID 18502781.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shevel E (2009). "Middle meningeal artery dilatation in migraine". Headache. 49(10): 1541–3. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01495.x. PMID 19656222.

- ^ a b Shevel E (2007). "Vascular Surgery for Chronic Migraine". Therapy. 4: 451–456.

- ^ Tfelt-Hansen P, Lous I, Olesen J. (1981). "Prevalence and significance of muscle tenderness during common migraine attacks". Headache. 21: 49–54. PMID 7239900.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Olesen J. (1978). "Some clinical features of the acute migraine attack. An analysis of 750 patients". Headache. 18: 268–271. PMID 721459.

- ^ Jensen K, Tuxen C, Olesen J (1988). "Pericranial muscle tenderness and pressure-pain threshold in the temporal region during common migraine". Pain. 35: 65–70. PMID 3200599.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tfelt-Hansen P, Lous I, Olesen J. (1981). "Prevalence and significance of muscle tenderness during common migraine attacks". Headache. 21: 49–54. PMID 7239900.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Trigger Point Therapy for Headaches & Migraines, DeLaune, Valerie (New Harbinger: 2008) [2]

- ^ Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Celentano DD, Reed ML (1992). "Undiagnosed migraine headaches. A comparison of symptom-based and reported physician diagnosis". Archives of Internal Medicine. 152 (6): 1273–8. doi:10.1001/archinte.152.6.1273. PMID 1599358.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schreiber CP, Hutchinson S, Webster CJ, Ames M, Richardson MS, Powers C (2004). "Prevalence of migraine in patients with a history of self-reported or physician-diagnosed 'sinus' headache". Archives of Internal Medicine. 164 (16): 1769–72. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.16.1769. PMID 15364670.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (2004). "The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition". Cephalalgia. 24 Suppl 1: 24. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00653.x. PMID 14979299.

- ^ Detsky ME, McDonald DR, Baerlocher MO, Tomlinson GA, McCrory DC, Booth CM (2006). "Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging?". JAMA. 296 (10): 1274–83. doi:10.1001/jama.296.10.1274. PMID 16968852.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R; et al. (2003). "A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: The ID Migraine validation study". Neurology. 61 (3): 375–82. PMID 12913201.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Modi S, Lowder DM (2006). "Medications for migraine prophylaxis". American Family Physician. 73 (1): 72–8. PMID 16417067.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Diener HC, Limmroth V (2004). "Medication-overuse headache: a worldwide problem". Lancet Neurology. 3 (8): 475–83. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00824-5. PMID 15261608.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fritsche G, Diener HC (2002). "Medication overuse headaches -- what is new?". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 1 (4): 331–8. doi:10.1517/14740338.1.4.331. PMID 12904133.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ van der Kuy PH, Lohman JJ (2002). "A quantification of the placebo response in migraine prophylaxis". Cephalalgia. 22 (4): 265–70. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00363.x. PMID 12100088.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Kaniecki R, Lucas S. (2004). "Treatment of primary headache: preventive treatment of migraine". Standards of care for headache diagnosis and treatment. Chicago: National Headache Foundation. pp. 40–52.

- ^ Silberstein SD, Lipton RB. (1994). "Overview of diagnosis and treatment of migraine". Neurology. 44(suppl 7): S6 – S16. PMID 7969947.

- ^ Jackson JL, Shimeall W, Sessums L; et al. (2010). "Tricyclic antidepressants and headaches: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 341: c5222. doi:10.1136/bmj.c5222. PMC 2958257. PMID 20961988.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Saper, JR; Lake, AE; Tepper, SJ (2001). "Nefazodone for chronic daily headache prophylaxis: an open-label study". Headache. 41 (5): 465–74. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.01084.x. PMID 11380644.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mylecharane, EJ (1991). "5-HT2 receptor antagonists and migraine therapy". Journal of neurology. 238 Suppl 1: S45–52. PMID 2045831.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Millan, MJ (2005). "Serotonin 5-HT2C receptors as a target for the treatment of depressive and anxious states: focus on novel therapeutic strategies". Therapie. 60 (5): 441–60. doi:10.2515/therapie:2005065. PMID 16433010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ "Aspirin and Migraine". National Headache Foundation. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- ^ K.A. Fackelmann (1990-02-17). "Low dose of aspirin keeps migraine away". Science News. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- ^ Dalessio. D.J. (1990-02-17). "Aspirin prophylaxis for migraine". ISSN 0098-7484. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

{{cite web}}: Text "JAMA, The Journal of the American Medical Association" ignored (help) - ^ Hennekens, Charles H., Buring, Julie E., Peto, Richard (1990). "Low-dose aspirin for migraine prophylaxis". JAMA, The Journal of the American Medical Association. ISSN 0098-7484. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18339350, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18339350instead. - ^ Shevel E (2007). "Vascular Surgery for Chronic Migraine". Future Medicine. 4: 451–456. doi:10.2217/14750708.4.4.451.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15622223, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15622223instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31817742da, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1097/PRS.0b013e31817742dainstead. - ^ Shi FY (1989). "[Morphological studies of extracranial arteries in patients with migraine]". Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi(Chinese). 18 (4): 271–3. PMID 2636957.

- ^ Hankemeier U (1985). "[Therapy of pulsating temporal headache. Resection of the

superficial temporal artery.]". Fortschr Med (German). 103 (35): 822–4. PMID 4054803.

{{cite journal}}: line feed character in|title=at position 58 (help) - ^ Sacristán HD, Ramírez AB (@9 April). "Tratamiento Quirurgico de las Jaquecas". Annales de la Real, X Sesion Cientifica (Spanish).

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ Rapidis AD (1976). "The therapeutic result of excision of the superficial temporal artery in atypical migraine". J Maxillofac Surg. 4 (3): 182–8. doi:10.1016/S0301-0503(76)80029-X. PMID 1066419.

- ^ Holland JT (1976). "Three cases of vascular headache treated by surgery". Proc Aust Assoc Neurol. 13: 51–4. PMID 1029006.

- ^ Florescu V, Florescu R (1975). "[Value of resection of the superficial temporal vasculo-nervous bundle in some cases of vascular headache.]". Rev Chir Oncol Radiol O R L Oftalmol Stomatol Otorinolaringol. (Romanian). 20 (2): 113–7. PMID 127294.

- ^ Bouche J, Freche C, Chaix G, Dervaux JL. (1974). "[Surgery by cryotherapy of the superficial temporal artery in temporo-parietal neuralgia]". Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. (French). 91 (1): 56–9. PMID 4603862.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cook N. (1973). "Cryosurgery of migraine". Headache. 12 (4): 143–50. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1973.hed1204143.x. PMID 4682552.

- ^ Cook N. (1978). "Cryosurgery of headache". Res Clin Stud Headache. 5: 86–101. PMID 674810.

- ^ Murillo CA (1968). "Resection of the temporal neurovascular bundle for control of migraine headache". Headache. 8: 112–117. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1968.hed0803112.x. PMC 1311613. PMID 573012.

- ^ Shevel E (2007). "Vascular Surgery for Chronic Migraine". Future Medicine. 4: 451–456. doi:10.2217/14750708.4.4.451.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite jstor}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by jstor:4016110, please use {{cite journal}} with

|jstor=4016110instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19048002, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19048002instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19172218, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19172218instead. - ^ Chaibi A, Tuchin PJ, Russell MB (2011). "Manual therapies for migraine: a systematic review". J Headache Pain. doi:10.1007/s10194-011-0296-6. PMID 21298314.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Millichap JG, Yee MM (2003). "The diet factor in pediatric and adolescent migraine". Pediatric Neurology. 28 (1): 9–15. doi:10.1016/S0887-8994(02)00466-6. PMID 12657413.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Rabbie R, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ (2010). "Ibuprofen with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10 (10): CD008039. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008039.pub2. PMID 20927770.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brandes JL, Kudrow D, Stark SR; et al. (2007). "Sumatriptan-naproxen for acute treatment of migraine: a randomized trial". JAMA. 297 (13): 1443–54. doi:10.1001/jama.297.13.1443. PMID 17405970.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kirthi V, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ (2010). "Aspirin with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4 (4): CD008041. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008041.pub2. PMID 20393963.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ (2010). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11: CD008040. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008040.pub2. PMID 21069700.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goldstein J, Hoffman HD, Armellino JJ; et al. (1999). "Treatment of severe, disabling migraine attacks in an over-the-counter population of migraine sufferers: results from three randomized, placebo-controlled studies of the combination of acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine". Cephalalgia. 19 (7): 684–91. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.019007684.x. PMID 10524663.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Migraine headaches" information from the Cleveland Clinic

- ^ a b Cady R, Dodick DW (2002). "Diagnosis and treatment of migraine". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 77 (3): 255–61. doi:10.4065/77.3.255. PMID 11888029.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); zero width space character in|doi=at position 9 (help) - ^ Johnston MM, Rapoport AM (2010). "Triptans for the management of migraine". Drugs. 70 (12): 1505–18. doi:10.2165/11537990-000000000-00000. PMID 20687618.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tepper SJ, Tepper DE (2010). "Breaking the cycle of medication overuse headache". Cleve Clin J Med. 77 (4): 236–42. doi:10.3949/ccjm.77a.09147. PMID 20360117.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Colman I, Friedman BW, Brown MD; et al. (2008). "Parenteral dexamethasone for acute severe migraine headache: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials for preventing recurrence". BMJ. 336 (7657): 1359–61. doi:10.1136/bmj.39566.806725.BE. PMC 2427093. PMID 18541610.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "4.7.4.1 Treatment of acute migraine". British National Formulary (55 ed.). 2008. p. 239.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Etminan, M; Takkouche, B; Isorna, FC; Samii, A (2005). "Risk of ischaemic stroke in people with migraine: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". BMJ. 330 (7482): 63. doi:10.1136/bmj.38302.504063.8F. PMC 543862. PMID 15596418.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ a b Kurth, T (2006). "Migraine and risk of cardiovascular disease in women". JAMA. 296 (3): 283–91. doi:10.1001/jama.296.3.283. PMID 16849661.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ medscape.com - Headache and Combination Estrogen-Progestin Oral Contraceptives:: Case 2

- ^ Becker, C; Brobert, GP; Almqvist, PM; Johansson, S; Jick, SS; Meier, CR (2007). "Migraine and the risk of stroke, TIA, or death in the UK (CME)". Headache. 47 (10): 1374–84. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00937.x. PMID 18052947.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Waters, WE; Campbell, MJ; Elwood, PC (1983). "Migraine, headache, and survival in women". British medical journal (Clinical research ed.). 287 (6403): 1442–3. PMC 1549656. PMID 6416449.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author-name-separator=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mortimer MJ, Kay J, Jaron A (1992). "Epidemiology of headache and childhood migraine in an urban general practice using Ad Hoc, Vahlquist and IHS criteria". Dev Med Child Neurol. 34 (12): 1095–101. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1992.tb11423.x. PMID 1451940.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Linet MS, Stewart WF, Celentano DD, Ziegler D, Sprecher M (1989). "An epidemiologic study of headache among adolescents and young adults". JAMA. 261 (15): e1197. doi:10.1001/jama.261.15.2211. PMID 2926969.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ziegler DK, Hassanein RS, Couch JR (1977). "Characteristics of life headache histories in a nonclinic population". Neurology. 27 (3): 265–9. PMID 557763.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ SELBY G, LANCE JW (1960). "Observations on 500 cases of migraine and allied vascular headache". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 23: 23–32. doi:10.1136/jnnp.23.1.23. PMC 495326. PMID 14444681.

- ^ a b Anttila P, Metsähonkala L, Sillanpää M (2006). "Long-term trends in the incidence of headache in Finnish schoolchildren". Pediatrics. 117 (6): e1197–201. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2274. PMID 16740819.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Lipton RB, Stewart WF (1993). "Migraine in the United States: a review of epidemiology and health care use". Neurology. 43 (6 Suppl 3): S6–10. PMID 8502385.

- ^ a b Rasmussen BK, Olesen J (1992). "Migraine with aura and migraine without aura: an epidemiological study". Cephalalgia. 12 (4): 221–8, discussion 186. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1992.1204221.x. PMID 1525797.

- ^ Steiner TJ, Scher AI, Stewart WF, Kolodner K, Liberman J, Lipton RB (2003). "The prevalence and disability burden of adult migraine in England and their relationships to age, sex and ethnicity". Cephalalgia. 23 (7): 519–27. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00568.x. PMID 12950377.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bigal ME, Liberman JN, Lipton RB (2006). "Age-dependent prevalence and clinical features of migraine". Neurology. 67 (2): 246–51. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000225186.76323.69. PMID 16864816.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stewart WF, Linet MS, Celentano DD, Van Natta M, Ziegler D (1991). "Age- and sex-specific incidence rates of migraine with and without visual aura". Am. J. Epidemiol. 134 (10): 1111–20. PMID 1746521.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wang SJ (2003). "Epidemiology of migraine and other types of headache in Asia". Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 3 (2): 104–8. doi:10.1007/s11910-003-0060-7. PMID 12583837.

- ^ Lavados PM, Tenhamm E (1997). "Epidemiology of migraine headache in Santiago, Chile: a prevalence study". Cephalalgia. 17 (7): 770–7. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1707770.x. PMID 9399008.

- ^ Ottman R, Lipton RB (1994). "Comorbidity of migraine and epilepsy". Neurology. 44 (11): 2105–10. PMID 7969967.

- ^ a b c Arulmani, U., "Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide and Migraine: Implications for Therapy" (2004). Doctoral thesis, Erasmus University. Web-link.

- ^ Brothwell, Don R. (1963). Digging up Bones; the Excavation, Treatment and Study of Human Skeletal Remains. London: British Museum (Natural History). p. 126. ISBN 0565007041. OCLC 14615536.

- ^ Edmeads, J. (1991). What is migraine? Controversy and stalemate in migraine pathophysiology. J Neurol, 238 Suppl 1, S2-5. DOI weblink.

- ^ Shevel E (2009). "Middle meningeal artery dilatation in migraine". Headache. 49(10): 1541–3. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01495.x. PMID 19656222.

- ^ Shevel E (2011). "The extracranial vascular theory of migraine: an artificial controversy". J Neural Transm. Jan 5: Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1007/s00702-010-0517-1. PMID 21207080.

- ^ Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe

- ^ "Migraine Relief on the Horizon?". CNN. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ^ Tepper SJ, Stillman MJ (2008). "Clinical and preclinical rationale for CGRP-receptor antagonists in the treatment of migraine". Headache. 48 (8): 1259–68. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01214.x. PMID 18808506.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Migraine cause 'identified' as genetic defect". BBC News. 2010-09-27.