Jefferson nickel: Difference between revisions

It will never survive FAC but I'm rather proud of that |

|||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

| Reverse2 Design Date = 2004 (upper) and 2005 (lower) |

| Reverse2 Design Date = 2004 (upper) and 2005 (lower) |

||

}} |

}} |

||

Since 1938, the '''Jefferson nickel''' has been the five-cent coin struck by the [[United States Mint]]. The obverse of the coin, since 2006, has featured a forward-facing portrayal of early U.S. president [[Thomas Jefferson]] by Jamie Franki. The coin's [[Obverse and reverse|reverse]] is the original by [[Felix Schlag]]; in 2004 and 2005, the piece bore commemorative designs. |

|||

First struck in 1913, the [[Buffalo nickel]] had long been difficult to coin, and after it completed the 25-year term during which it could only be replaced by Congress, the Mint moved quickly to replace it with a new design. The Mint conducted a design competition in early 1938, requiring that Jefferson be depicted on the obverse, and Jefferson's house, [[Monticello]] on the reverse. Schlag won the competition, but was required to submit an entirely new reverse and make other changes before the new piece went into production in October 1938. |

First struck in 1913, the [[Buffalo nickel]] had long been difficult to coin, and after it completed the 25-year term during which it could only be replaced by Congress, the Mint moved quickly to replace it with a new design. The Mint conducted a design competition in early 1938, requiring that Jefferson be depicted on the obverse, and Jefferson's house, [[Monticello]] on the reverse. Schlag won the competition, but was required to submit an entirely new reverse and make other changes before the new piece went into production in October 1938. |

||

Revision as of 16:57, 27 April 2011

United States | |

| Value | 0.05 U.S. dollar |

|---|---|

| Mass | 5.000 g (0.1615 troy oz) |

| Diameter | 21.21 mm (0.835 in) |

| Thickness | 1.95 mm (0.077 in) |

| Edge | Plain |

| Composition | 75% copper 25% nickel "Wartime Nickels" (mid-1942 to 1945) 56% copper 35% silver 9% manganese |

| Years of minting | 1938 – present |

| Obverse | |

| File:2006 Nickel Proof Obv.png | |

| Design | Thomas Jefferson |

| Designer | Jamie Franki |

| Design date | 2006–present |

| File:NickelObverses.jpg | |

| Design date | 1938–2004 (left) and 2005 (right) |

| Reverse | |

| |

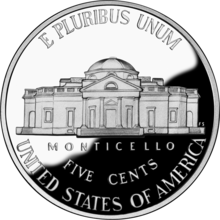

| Design | Monticello |

| Designer | Felix Schlag |

| Design date | 1938–2003 and 2006–present |

| File:NickelReverses.jpg | |

| Design date | 2004 (upper) and 2005 (lower) |

Since 1938, the Jefferson nickel has been the five-cent coin struck by the United States Mint. The obverse of the coin, since 2006, has featured a forward-facing portrayal of early U.S. president Thomas Jefferson by Jamie Franki. The coin's reverse is the original by Felix Schlag; in 2004 and 2005, the piece bore commemorative designs.

First struck in 1913, the Buffalo nickel had long been difficult to coin, and after it completed the 25-year term during which it could only be replaced by Congress, the Mint moved quickly to replace it with a new design. The Mint conducted a design competition in early 1938, requiring that Jefferson be depicted on the obverse, and Jefferson's house, Monticello on the reverse. Schlag won the competition, but was required to submit an entirely new reverse and make other changes before the new piece went into production in October 1938.

As nickel was a strategic war material during World War II, nickels coined from 1942 to 1945 were struck in a copper-silver-manganese alloy which would not require adjustment to vending machines, and bear a large mintmark above the depiction of Monticello on the reverse. In 2004 and 2005, the nickel saw new designs as part of the Westward Journey nickel series, and since 2006 has borne Schlag's reverse and Franki's obverse.

Inception

The design for the Buffalo nickel is well-regarded today, and has appeared both on a commemorative silver dollar and a bullion coin. However, during the time it was struck (1913–1938), it was less well liked, especially by Mint authorities, whose attempts to bring out the full design increased an already high rate of die breakage. In 1938, it had been struck for 25 years, thus becoming eligible to be replaced by action of the Treasury, rather than by Congress. The Mint moved quickly and without public protest to replace the coin.[1]

In late January 1938, the Mint announced an open competition for the new nickel design, with the winner to receive a prize of $1,000. The deadline for submissions was April 15; Mint Director Nellie Tayloe Ross and three sculptors were to be the judges. That year saw the bicentennial of the birth of early US President Thomas Jefferson; competitors were to place a portrait of Jefferson on the obverse, and a depiction of his house, Monticello on the reverse.[2]

By mid-March, few entries had been received. This seeming lack of response proved to be misleading, as many artists planned on entering the contest and would submit designs near the deadline. On April 20, the judges viewed 390 entries; four days later, Felix Schlag was announced as the winner.[3] Schlag had been born in Germany and had come to the United States only nine years previously.[4] Either through a misunderstanding or an oversight, Schlag did not include his initials in the design; they would not be added until 1966.[5] The bust of Jefferson on the obverse closely resembles his bust by sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon, which is to be found in Boston's Museum of Fine Arts.[6]

In early May, it was reported that the Mint required some changes to Schlag's design prior to coining. Schlag's original design showed a three-quarters view of Monticello, including a tree. Officials disliked the lettering Schlag had used, a style much narrower than on the eventual coin. The tree was another source of official animus; officials decided it was a palm tree and incorrectly believed Jefferson could not have been growing such a thing. A formal request for changes was sent to Schlag in late May. The sculptor was busy with other projects and did not work on the nickel until mid-June. When he did, he changed the reverse to a plain view, or head-on perspective, of Monticello.[7] Art historian Cornelius Vermeule described the change:

Official taste eliminated this interesting, even exciting, view, and substituted the mausoleum of Roman profile and blurred forms that masquerades as the building on the finished coin. On the trial reverse the name "Monticello" seemed scarcely necessary and was therefore, logically, omitted. On the coin as issued it seems essential lest one think the building portrayed is the vault at Fort Knox, a state archives building, or a public library somewhere.[8]

The designs were submitted to the Commission of Fine Arts for their recommendation in mid-July, the version submitted included the new version of Monticello but may not have included the revised lettering. Commission chairman Charles Moore asked that the positions of the mottos on the reverse be switched, with the country name at the top; this was not done. After the Fine Arts Commission recommendation, the Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau approved the design.[7]

On August 21, the Anderson (Indiana) Herald noted:

[T]he Federal Fine Arts Commission ... didn't like the view of Thomas Jefferson's home, Monticello, so they required the artist to do another picture of the front of the house. They did not like the lettering on the coin. It wasn't in keeping, but they forgot to say what it wasn't in keeping with ... There is no more reason for imitating the Romans in this respect [by using Roman-style lettering on the coin] than there would be for modeling our automobiles after the chariot of Ben Hur's day.[4]

Early production; World War II changes (1938–1945)

Production of the Jefferson nickel began at all three mints on October 3, 1938. By mid-November, some twelve million had been coined (more than thirty million would be struck in 1938) and they were officially released into circulation on November 15.[9] According to contemporary accounts, the Jefferson nickel was initially hoarded, and it was not until 1940 that it was commonly seen in circulation.[10]

In 1939, the Mint recut the hub for the nickel, sharpening the steps on Monticello, which had been fuzzy in initial strikings. Since then, a test for whether a nickel is particularly well struck is whether all six steps appear clearly, with "full step" nickels more collectable.[11]

With the entry of the United States into World War II, nickel became a critical war material, and the Mint sought to reduce its use of the metal. On March 27, 1942, Congress authorized a nickel made of 50% copper and 50% silver, but gave the Mint the authority to vary the proportions, or add other metals, in the public interest. The Mint's greatest concern was in finding an alloy which would use no nickel, but still satisfy counterfeit detectors in vending machines. An alloy of 56% copper, 35% silver and 9% manganese proved suitable, and this alloy began to be coined into nickels beginning in October 1942. In the hopes of making them easy to sort out and withdraw after the war, the Mint struck all "war nickels" with a large mintmark appearing above Monticello. The mintmark P for Philadelphia was the first time that mint's mark had appeared on a US coin. The prewar composition, and smaller mintmark (or omitted for Philadelphia) were resumed in 1946. In a 2000 article in The Numismatist, Mark A. Benvenuto suggested that the amount of nickel saved by the switch was not significant to the war effort, but that the war nickel served as an ubiquitous reminder of the sacrifices that needed to be made for victory.[12]

Later production (1946–2003)

When it became known that the Denver Mint had struck only 2,630,030 nickels in 1950, the 1950-D began to be widely hoarded. Speculation in them increased in the early 1960s, but prices decreased sharply in 1964. Because they were so widely pulled from circulation, the 1950-D is readily available today. A variety was created in 1955 with the end (for the time) of minting at the San Francisco Mint. A number of leftover reverse dies with S mintmark were used in Denver, overpunched with a D.[13]

Proof coins, struck at Philadelphia, had been minted for sale to collectors in 1938.[14] Discontinued in 1942, sales of proofs began again in 1950 and continued until 1964, when striking of proof coins was discontinued during the coin shortage. Proof coin sales resumed in 1968, but with coins struck at the reopened San Francisco facility. In 1968, after three years of coins with no mintmarks to represent place of origin, they returned, but moved to the lower part of the obverse, to the right of Jefferson's bust.[15] Beginning in 1971, no nickels were struck for circulation in San Francisco—the 1971-S was the first nickel struck in proof only since 1878.[16]

The Mint repeatedly modified the design in the following years. In 1982, the steps were sharpened in that year's redesign. The 1987 modification saw the sharpening of Jefferson's hair and the details of Monticello—since 1987, well-struck nickels with six full steps on the reverse have been relatively common. In 1993, Jefferson's hair was again sharpened.[17]

Westward Journey nickels; redesign of obverse (2003–present)

In June 2002, Mint officials were interested in redesigning the nickel in honor of the upcoming bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. They contacted the office of Representative Eric Cantor (Republican-Virginia). Cantor was concerned at the idea of moving Monticello, located in his home state, off the nickel, and sponsored legislation which would allow the Mint to strike different designs in 2003, 2004, and 2005, and again depict Monticello beginning in 2006.[18] The resultant act, the "American 5-Cent Coin Design Continuity Act of 2003", Public Law 108-15, 117 Stat. 615, was signed into law on April 23, 2003. Under its terms, the Treasury Secretary could vary the nickel's designs in honor of the 200th anniversary of the Expedition and of the Louisiana Purchase, but the nickel would again feature Jefferson and Monticello beginning in 2006.[19] Under Cantor's legislation, a provision was inserted into the law, which now requires that any five cent coin, without time limit, depict Jefferson and Monticello.[20]

In November 2003, the Mint announced the first two reverse designs, to be struck with Schlag's obverse in 2004.[21] The first, designed by United States Mint sculptor/engraver Norman E. Nemeth, depicts an adaptation of the Indian Peace Medals struck for Jefferson. The second, by Mint sculptor/engraver Al Maletsky, depicts a keelboat like that used by the Expedition.[22]

The 2005 nickels presented a new image of Jefferson, designed by Joe Fitzgerald based on a 1789 bust of Jefferson by Jean-Antoine Houdon.[23] The word "Liberty" was taken from Jefferson's handwritten draft for the Declaration of Independence, though to achieve a capital L, Fitzgerald had to obtain one from other documents written by Jefferson.[24] The reverse for the first half of the year depicted an American bison, recalling the Buffalo nickel and designed by Jamie Franki. The reverse for the second half showed a coastline and the words "Ocean in view! O! The Joy!", from a journal entry by William Clark.[23] Clark had actually written the word as "ocian", but the Mint corrected the spelling.[24]

The obverse design for the nickel debuting in 2006 was designed by Franki. It depicts a forward-facing Jefferson based on a 1800 study by Rembrandt Peale, and includes "Liberty" in Jefferson's script. According to Acting Mint Director David Lebryk, "The image of a forward-facing Jefferson is a fitting tribute to [his] vision."[25] The reverse beginning in 2006 was again Schlag's Monticello design, but newly sharpened by Mint engravers.[26] As Schlag's obverse design, on which his initials were placed in 1966, is no longer used, his initials were placed on the reverse to the right of Monticello.[27]

In 2009, a total of 86,640,000 nickels were struck for circulation.[28] The figure rebounded in 2010 to 490,560,000.[29] The unusually low 2009 figures were caused by a lack of demand for coins due to poor economic conditions.[30]

References

- ^ Bowers, p. 127.

- ^ Bowers, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Bowers, p. 129.

- ^ a b Taxay, p. 369.

- ^ Bardes, Herbert C. Nickel designer gains his place. The New York Times, July 24, 1966, p. 85. Retrieved on April 7, 2011. Fee for article.

- ^ Vermeule, pp. 205–206.

- ^ a b Bowers, pp. 129–131.

- ^ Vermeule, p. 207.

- ^ Bowers, pp. 141–143.

- ^ Lange, p. 167.

- ^ Bowers, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Bowers, pp. 146–148.

- ^ Bowers, p. 149

- ^ Bowers, p. 143.

- ^ Bowers, pp. 259–260.

- ^ Bowers, p. 222.

- ^ Bowers, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Va. legislators want to keep their nickel back. AP via USA TODAY, July 23, 2002. Retrieved on April 7, 2011.

- ^ Nation to get newly-designed nickels. United States Mint, April 24, 2003. Retrieved on April 7, 2011.

- ^ U.S. Code, Title 31, Section 5112. Cornell University Law School. Retrieved on April 20, 2011.

- ^ Anderson, Gordon T. U.S. to get two new nickels. CNN Money, November 6, 2003. Retrieved on April 7, 2011.

- ^ The 2004 Westward Journey nickel series designs. United States Mint. Retrieved on April 7, 2011.

- ^ a b The 2005 Westward Journey nickel series designs. United States Mint. Retrieved on April 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Frazier, Joseph. New nickel recalls historic moment. AP via Eugene Register-Guard, August 5, 2005, p. C7. Retrieved on April 7, 2011.

- ^ US unveils forward-looking nickel. BBC, October 6, 2005. Retrieved on April 8, 2011.

- ^ The 2006 Westward Journey nickel series designs. United States Mint. Retrieved on April 8, 2011.

- ^ Jefferson nickels. Collectors Weekly. Retrieved on April 12, 2011.

- ^ 2009 coin production. United States Mint. Retrieved on April 20, 2011.

- ^ 2010 coin production. United States Mint. Retrieved on April 20, 2011.

- ^ Unser, Darrin Lee. US coin mintages plummeted as Mint cut production. Coin News, January 20, 2010. Retrieved on April 20, 2011.

Bibliography

- Bowers, Q. David (2007). A Guide Book of Buffalo and Jefferson Nickels. Atlanta, Ga.: Whitman Publishing LLC. ISBN 0-7948-2008-5.

- Breen, Walter (1988). Walter Breen's Complete Encyclopedia of U.S. and Colonial Coins. New York, N.Y.: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-14207-2.

- Taxay, Don (1983). The U.S. Mint and Coinage. New York, N.Y.: Sanford J. Durst Numismatic Publications. ISBN 0-915262-68-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editon=ignored (|edition=suggested) (help) - Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674628403.