Shimer Great Books School: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 428570959 by 194.144.188.195 (talk) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

| logo = [[File:Shimer College Logo.PNG|170px|alt=white tree above number 1853 on maroon octagonal background with year 1853 next to words Shimer The Great Books College of Chicago]] |

| logo = [[File:Shimer College Logo.PNG|170px|alt=white tree above number 1853 on maroon octagonal background with year 1853 next to words Shimer The Great Books College of Chicago]] |

||

| website = [http://www.shimer.edu/ shimer.edu] |

| website = [http://www.shimer.edu/ shimer.edu] |

||

}}'''Shimer College''' (often shortened to '''Shimer'''; {{pron-en|ˈʃaɪmər|En-us-Shimer.ogg}} {{Respell|SHY|mər}}) is a very small, private, undergraduate [[liberal arts]] college in [[Chicago]], Illinois, in the United States. Founded by [[Frances Shimer|Frances Wood Shimer]] in 1853 in the frontier town of [[Mt. Carroll, Illinois]], it was a women's school for most of its first century. It joined with the [[University of Chicago]] (U. of C.) in 1896, and became one of the first [[junior college]]s in the country in 1907. In 1950, it became a co-educational four-year college, took the name Shimer College, and adopted the Hutchins Plan of Great Books and [[Socratic method|Socratic]] seminars then in practice at the U. of C. The U. of C. relationship ended in 1958. Shimer enjoyed national recognition and strong growth in the 1960s but was forced by financial problems to abandon its campus in 1978. The college then moved to an improvised campus in the Chicago suburb of [[Waukegan, Illinois|Waukegan]], remaining there until 2006, when it moved to the [[Illinois Institute of Technology Academic Campus|campus]] of the [[Illinois Institute of Technology]] (IIT) in the [[Douglas, Chicago#Bronzeville|Bronzeville]] neighborhood in the Douglas [[Community areas of Chicago|community area]] of Chicago. |

}}'''Shimer College''' (often shortened to '''Shimer'''; {{pron-en|ˈʃaɪmər|En-us-Shimer.ogg}} {{Respell|SHY|mər}}) is a very small, private, undergraduate [[liberal arts]] college in [[Chicago]], Illinois, in the United States. Founded by [[Frances Shimer|Frances Wood Shimer]] in 1853 in the frontier town of [[Mt. Carroll, Illinois]], it was a women's school for most of its first century. It joined with the [[University of Chicago]] (U. of C.) in 1896, and became one of the first [[junior college]]s in the country in 1907. In 1950, it became a co-educational four-year college, took the name Shimer College, and adopted the Hutchins Plan of Great Books and [[Socratic method|Socratic]] seminars then in practice at the U. of C. The U. of C. relationship ended in 1958. Shimer enjoyed national recognition and strong growth in the 1960s but was forced by financial problems to abandon its campus in 1978. The college then moved to an improvised campus in the Chicago suburb of [[Waukegan, Illinois|Waukegan]], remaining there until 2006, when it moved to the [[Illinois Institute of Technology Academic Campus|campus]] of the [[Illinois Institute of Technology]] (IIT) in the [[Douglas, Chicago#Bronzeville|Bronzeville]] neighborhood in the Douglas [[Community areas of Chicago|community area]] of Chicago.FREE EARL! |

||

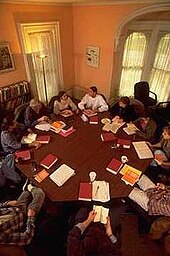

Classes are exclusively small seminars in which students discuss original source material rather than read textbooks. The core curriculum, a sequence of courses in the humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, and [[interdisciplinarity|integrated studies]], makes up two thirds of the course work required for a degree. Shimer has offered a [[study abroad]] program in [[Oxford, England]], since 1963 and a weekend program for working adults since 1981. Applicants to the school are evaluated on their academic potential, based primarily on an essay. No minimum grades or test scores are required. The [[Early entrance at Shimer College|Early Entrant Program]], in place since 1950, allows students who have not yet completed high school to start college early. Shimer has the third highest rate of doctoral productivity of any liberal arts college in the country. Fifty percent of students go on to graduate study; twenty percent complete doctoral degrees. |

Classes are exclusively small seminars in which students discuss original source material rather than read textbooks. The core curriculum, a sequence of courses in the humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, and [[interdisciplinarity|integrated studies]], makes up two thirds of the course work required for a degree. Shimer has offered a [[study abroad]] program in [[Oxford, England]], since 1963 and a weekend program for working adults since 1981. Applicants to the school are evaluated on their academic potential, based primarily on an essay. No minimum grades or test scores are required. The [[Early entrance at Shimer College|Early Entrant Program]], in place since 1950, allows students who have not yet completed high school to start college early. Shimer has the third highest rate of doctoral productivity of any liberal arts college in the country. Fifty percent of students go on to graduate study; twenty percent complete doctoral degrees. |

||

Revision as of 12:40, 11 May 2011

| Torch with four vases on black background, in which circle with words Shimer College and year 1853 Shimer College Seal | |

Former names | Mount Carroll Seminary Frances Shimer Academy Frances Shimer Junior College |

|---|---|

| Motto | Non Ministrari Sed Ministrare |

Motto in English | Not to be served, but to serve |

| Type | Private, Coeducational, Undergraduate, Liberal arts[1] |

| Established | 1853 |

| Endowment | $250,000 (2008)[2] |

| President | Edward J. Noonan (interim)(2010) |

Academic staff | 15 (2009) |

| Students | 104 (2009)[3] |

| Location | , Illinois , United States 41°49′55″N 87°37′33″W / 41.83194°N 87.62583°W |

| Campus | Urban |

| Colors | Burgundy and gold |

| Mascot | Flaming Smelt[4] |

| Website | shimer.edu |

| white tree above number 1853 on maroon octagonal background with year 1853 next to words Shimer The Great Books College of Chicago | |

Shimer College (often shortened to Shimer; Template:Pron-en SHY-mər) is a very small, private, undergraduate liberal arts college in Chicago, Illinois, in the United States. Founded by Frances Wood Shimer in 1853 in the frontier town of Mt. Carroll, Illinois, it was a women's school for most of its first century. It joined with the University of Chicago (U. of C.) in 1896, and became one of the first junior colleges in the country in 1907. In 1950, it became a co-educational four-year college, took the name Shimer College, and adopted the Hutchins Plan of Great Books and Socratic seminars then in practice at the U. of C. The U. of C. relationship ended in 1958. Shimer enjoyed national recognition and strong growth in the 1960s but was forced by financial problems to abandon its campus in 1978. The college then moved to an improvised campus in the Chicago suburb of Waukegan, remaining there until 2006, when it moved to the campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in the Bronzeville neighborhood in the Douglas community area of Chicago.FREE EARL!

Classes are exclusively small seminars in which students discuss original source material rather than read textbooks. The core curriculum, a sequence of courses in the humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, and integrated studies, makes up two thirds of the course work required for a degree. Shimer has offered a study abroad program in Oxford, England, since 1963 and a weekend program for working adults since 1981. Applicants to the school are evaluated on their academic potential, based primarily on an essay. No minimum grades or test scores are required. The Early Entrant Program, in place since 1950, allows students who have not yet completed high school to start college early. Shimer has the third highest rate of doctoral productivity of any liberal arts college in the country. Fifty percent of students go on to graduate study; twenty percent complete doctoral degrees.

Shimer resides on the IIT main campus, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2005. There, students maintain Shimer College traditions but also participate in IIT student life. Shimer practices democratic self-governance to an extent that it states "is rare among institutions of higher education".[5] Since 1977, the college has been governed internally by faculty, staff, and students working through a structure of committees and an egalitarian deliberative body called the Assembly. Shimer enrolled 104 students in 2009.[3] Notable alumni include poets, authors, political theorists, experimental artists, and computing pioneers.

History

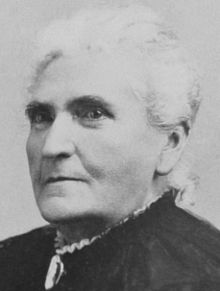

Shimer was founded in 1852, when the pioneer town of Mt. Carroll, Illinois, lacking a public school, incorporated the Mt. Carroll Seminary with no land, no teachers, and no money.[7][8][a] The town persuaded two schoolteachers from Ballston Spa, New York, Frances Wood and her friend Cindarella Gregory, to come west to the prairie to teach, and on May 11, 1853, the new seminary opened with 11 students in a local church.[9] Failing to raise enough money locally, the incorporators borrowed enough money to construct a building in 1854; discouraged by the financial picture, however, they sold the school to Wood and Gregory, who borrowed the money to buy it.[8] In 1857, Wood married Henry Shimer, a mason to whom the seminary owed money, who gave Wood, and later the school, his name.[10]

In 1864, the school began accepting only female students, not on principle, but because the school was out of space.[11] Wishing to ensure the long-term survival of the school, in 1896 Frances Shimer reached an agreement with the University of Chicago (U. of C.), under which the school became the Frances Shimer Academy of the University of Chicago, affiliated loosely with the Baptist Church.[12][13][b] Then Frances Shimer retired to Florida, never setting foot on campus again; she died in 1901.[14] William Rainey Harper, then president of the U. of C., was the first to champion the idea of the Junior College in the United States, and in 1907, Shimer became one of the first schools to offer a junior college program.[13][15] The two-year junior college program, which operated alongside the original preparatory program, was accredited in 1920.[16]

The college suffered a severe decline in enrollment and subsequent financial hardship during and after the Great Depression, which it survived — under five different presidents — in part by reorganizing the six-year preparatory program into a four-year junior college program and in part through deep salary reductions.[17] In 1943, Shimer president Albin Bro invited the Department of Education at the U. of C. to evaluate the entire college community. The 77 recommendations they returned would become the basis for Shimer's transformation from a conservative finishing school to a nontraditional, co-educational four-year college.[18]

The school was renamed Shimer College in 1950, and adopted the Great Books curriculum then in place at the U. of C.[13] The U. of C. connection was dissolved in 1958, following the U. of C.'s decision to abandon the Great Books plan and a narrowly averted Shimer bankruptcy in 1957.[19] The Great Books program at Shimer lived on, and the school achieved national recognition and rapid growth in enrollment through the 1960s.[20] In 1963, a Harvard Educational Review article named Shimer as one of 11 colleges with an "ideal intellectual climate".[21] A 1966 article in the education journal Phi Delta Kappan reported that Shimer "present[ed] impressive statistical evidence that their students are better prepared for graduate work in the arts and sciences and in the professions than those who have specialized in particular areas."[22]

In the late 1960s, Shimer experienced a period of internal unrest known as the "Grotesque Internecine Struggle," involving disputes over curriculum changes, the extent to which student behavior should be regulated, and allegedly inadequate fundraising by president Joe Mullin; half of the faculty and a large portion of the student body departed as a result.[23][24] As financial problems worsened, the school's survival was in doubt. The trustees voted to close the college at the end of 1973, but the school was saved by a desperate fund-raising campaign led by students and faculty.[25][26] Three times in the next four years, the trustees voted to shut the school down, only to later vote to reopen it.[27] Finally filing for bankruptcy in 1977, the trustees, in the words of board chair Barry Carroll, "put responsibility for the school's continuing on the shoulders of a very dedicated faculty of 12 and students who volunteered",[27] under the leadership of Don Moon, a nuclear engineer and Episcopal priest who had joined the faculty in 1967.[28]

I don't care if we only pay our way for a time, if we can ultimately have a school that will be appreciated.

Accepting an invitation from the city of Waukegan, Illinois, a declining industrial suburb north of Chicago, the faculty and 62 students borrowed trucks and moved the college into two "run down"[30] homes over Christmas break in 1978.[30] Classes began on schedule in January 1979. The college emerged from bankruptcy in 1980, but lost its accreditation as a result of its financial problems.[31] Over the next 25 years, Shimer purchased 12 of the surrounding homes to form a makeshift campus and slowly progressed towards financial stability.[32] By 1988, enrollment had climbed from a low of 40 to 114 and income exceeded expenses. Shimer won a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) in 1991, with the help of then NEH chair and core-curriculum advocate Lynne Cheney; the grant helped the school raise US$2 million and revitalized fund raising.[29][32] That same year, Shimer's accreditation was restored by the Higher Learning Commission of the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools.[33]

In 2006, Shimer, again struggling with stagnating enrollment, accepted an invitation to move, this time to the campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in Chicago, under a long-term lease agreement; the two institutions kept separate faculties and boards.[34][35] Shimer attracted national attention in 2009 when the school became embroiled in "a battle over what some saw as a right-wing attempt to take over its board and administration".[36][37] Students, organized under the name Shimer Student Alliance, protested at the February 2010 Board meeting.[38][39] Following votes of no confidence by the faculty, the alumni, and the Assembly (Shimer's democratic governing body), president Thomas Lindsay stepped down in April 2010.[40] He was succeeded by Ed Noonan, a Chicago-area architect and longtime Trustee of the college.[40]

Academics

Great Books program

Shimer is one of four Great Books colleges in the US.[41][42][c] The Great Books movement began with the work of John Erskine, who founded a Socratic seminar using great books at Columbia University in 1919.[43] This seminar profoundly impacted Erskine's colleague Mortimer Adler, who came to believe that the purpose of education was to engage student's minds "in the study of individual works of merit ... accompanied by a discussion of the ideas, the values, and the forms embodied in such products of human art."[44] Robert Maynard Hutchins, who led the University of Chicago from 1929 to 1951, brought Adler to the U. of C. and wholeheartedly embraced his ideas.[45][46][d] In 1931, Hutchins implemented the "Chicago Plan", which later became known as the "Hutchins Plan".[47]

The Chicago program comprised sequences in the natural sciences, the humanities, and the social sciences which were supposed to integrate past and present work within these divisions of knowledge. In addition, these sequences were capped by work in philosophy and history. The emphasis in teaching was on small classes with bright students, where discussion could supplant monologue as the dominant pedagogic technique.... At the same time, in order to retain high academic standards and contact with the "frontiers of knowledge", the College's pedagogy emphasized reading originals (sometimes although not invariably, defined as Great Books).[22][e]

Shimer, which had been affiliated with the U. of C. since 1896, adopted the Hutchins plan entirely in 1950, including the Chicago syllabi, comprehensive examinations, and several of their instructors.[48] The U. of C. abandoned the program after Hutchins left in 1951, but Shimer maintained it, and has done so through the decades that followed.

... that the best way to a liberal education in the West is through the greatest works the West has produced, is still, in our view, the best educational idea there is.

The 200-book reading list remains largely faithful to the original Hutchins plan, but new works are judiciously added to the core curriculum; these have included voices originally overlooked in the formation of the canon.[50] It now includes, for example, works by Martin Luther King, Jr., Carol Gilligan, Frantz Fanon, and Michel Foucault, along with other contemporary authors.[50] Readings are organized by broad historical and philosophical themes, rather than conventional fields. Small seminars are the sole form of instruction; even the natural sciences are taught via discussion. The classes, which are composed of on average eight and no more than twelve students, read and discuss only original source material.[41] Faculty are referred to as "facilitators" and are always addressed by first name. Teachers facilitate discussion but may talk little in the learning process, which Shimer calls "shared inquiry", in which "the text is the teacher, and thus the faculty member's role is to facilitate interaction between the text and the students."[48]

Curriculum

Shimer awards bachelor's degrees with concentrations in humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Two-thirds of the courses required for graduation are mandatory core courses. The remainder are electives, three-quarters of which must be in the student's chosen area of concentration. Electives offer in-depth work in a particular field, or basic skills instruction in languages and mathematics, and are often offered as "tutorials" with only one or two students per course.[51] Students may cross-register for courses at IIT and the Vandercook College of Music, also located on the IIT campus; courses available in this fashion include laboratory science, advanced mathematics, and music history and theory.[52]

Core

The core curriculum of Shimer College is a sequence of 16 required courses in humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, and interdisciplinary studies. The Basic Studies courses, numbered one and two, are generally taken during the first two years, and the Advanced Studies courses, numbered three and four, during the final two years. The Advanced Integrative Studies courses, numbered five and six, are taken in the senior year.[53]

| Humanities | Social sciences | Natural sciences | Integrative studies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | Art and Music | Society, Culture, and Personality | Laws and Models in Chemistry | Analysis, Logic, and Rhetoric |

| Two | Poetry, Drama, and Fiction | The Western Political Tradition | Evolution, Genetics, and Animal Behavior | The Nature and Creation of Mathematics |

| Basic Studies Comprehensive Examination | ||||

| Three | Philosophy and Theology | Modern Theories of State and Society | Light, Motion, and Scientific Explanation | |

| Four | Critical Evaluation in the Humanities (Enlightenment to the Present) | Methodology in the Social Sciences | Quantum Physics and Molecular Biology | |

| Area Studies Comprehensive Examination | ||||

| Five | History and Philosophy of Western Civilization: From the Ancient World Through the Middle Ages | |||

| Six | History and Philosophy of Western Civilization: From the Middles Ages Through the Nineteenth Century | |||

| Senior Thesis | ||||

The humanities core begins with the study of visual art and music and progresses through literature, philosophy and theology. It culminates with the final course, "Critical Evaluation in the Humanities," which seeks to unify the Humanities courses by approaching all of the areas of the Humanities theoretically through critical evaluation of significant works of the 18th century and later. The course includes Martin Buber's I and Thou, Immanuel Kant's Critique of Judgment, Friedrich Nietzsche's Beyond Good and Evil, and Søren Kierkegaard's Fear and Trembling.[55]

The social sciences sequence begins with study of the individual and society in the first course, proceeds to classical political thought in the second, then modern social and political theory in the third, and concludes with the "Theories of Social Inquiry" course, which focuses on statistical and interpretive methods in sociology, linguistic theory, and 20th century social thought, through works like Clifford Geertz's The Interpretation of Cultures, Paolo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Michel Foucault's Discipline and Punish, and Karl Mannheim's Ideology and Utopia.[56]

The natural sciences core studies science as it has developed historically, beginning with the presocratic philosophers of the 6th century BC and the theory of atoms in the first course; evolution, genetics, and animal behavior in the second; optics and the theory of relativity in the third; and concluding with the study of quantum physics and molecular biology. The natural science reading list includes Albert Einstein’s Relativity, Isaac Newton’s Opticks, Richard Feynman’s QED, Antoine Lavoisier’s Elements of Chemistry, and Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species.[57]

The first basic integrative studies course teaches the fundamental skills in close reading and argumentation required to work with original source texts. In the second course, logic and mathematics are studied in terms of the development of geometry and axiomatic systems in ancient and modern times.[53] The advanced integrative studies courses, in which students explore connections between the course texts and those they have studied in other courses, are the capstone of the Shimer curriculum. The readings are arranged chronologically in a unified, full-year sequence to demonstrate their historical relationships, beginning with the ancient epic poems The Epic of Gilgamesh and Homer's Iliad and concluding with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Faust and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's Reason in History.[58]

Writing projects, comprehensive examinations, and thesis

Students are required to complete a Semester Project during the final week of each term (known as Writing Week), on a topic they choose in conjunction with their advisor. The project does not receive a grade, but is reviewed by the student's instructors in a Final Conference and must be accepted before the student can register for the following semester. Students are also required to complete a separate substantial research paper before registering for the Advanced Integrative Studies courses.[59]

Students must pass at least two comprehensive examinations to graduate. Each comprehensive examination involves several days of reading and writing, and may include an oral component as well. After completing the Basic Studies courses, all students must pass the Basic Studies Comprehensive Examination to continue on to higher level courses.[53] After completing the Advanced Studies courses, students must pass at least one Area Studies Comprehensive Examination, usually in their area of concentration. [59]

The academic experience culminates with the Senior Thesis. Completed during the course of the student's fourth year, it usually takes the form of an analytical or expository essay, but may be a piece of original fiction, poetry, a performance, or a work of visual art. Students are encouraged to defend their theses orally and the public is invited to these defenses.[59]

Special programs

The Weekend College Program, founded in 1981, allows working adults to participate in an intensive schedule of classes which meet every third weekend, to allow them to graduate in four years.[60][61] Weekend students have ranged from 23 to 70 years of age and come from all over the country; weekend students have commuted from as far as Florida and New York.[62] The program enrolled 35 to 40 students in 2010.[63]

Shimer first offered a year of study abroad, in Paris, in 1961 and has held the program biennially in Oxford, England, since 1963.[64][65] The Shimer-in-Oxford program allows eight to fifteen students to spend either one or two semesters in Oxford with a Shimer professor.[66] The students, who are in their third and fourth years, take one course from the core curriculum each term and the remainder of their work as individual or very small group tutorials with academics from in and around the University of Oxford in subjects the students select themselves.[67] The Shimer-in-Oxford program is now affiliated with the Oxford Study Abroad Programme, founded in 1985, which allows students to share housing with students from Oxford University and other American colleges.[68]

The Teaching Fellows Program offers a graduate-level Great Books course designed for kindergarten through 12th grade school teachers. Shimer does not award graduate degrees, but teachers earn professional development credit through the program. The program complements traditional education courses by providing the background knowledge required for teachers to give more content-rich instruction.[69] The program was developed in conjunction with the Core Knowledge Foundation, which was founded in 1986 by E.D. Hirsch, Jr., author of Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know,[70] to promote a common core of learning in elementary school education.[71]

The Great Books + Law program, launched in 2007, is offered in conjunction with the Chicago-Kent College of Law (the Law School of the Illinois Institute of Technology). It allows students to count their first year of law school towards their Shimer degree and receive their J.D. in a total of five years instead of seven.[72] A joint program has also been operated since 2009 with Harold Washington College (HWC), one of the very few community colleges to offer a Great Books program. The program allows HWC students to take one Shimer course,[73] and is meant to encourage students to transfer to Shimer to complete their bachelor's degree.[74]

Faculty

As of 2009, Shimer had 11 full-time and 2 part-time faculty; 12 of the 13 hold doctorate degrees.[75] Four of those faculty members were among those who brought the school to Waukegan in 1978; the average tenure is 21 years.[76] The student-faculty ratio is eight to one.[75] Shimer instructors teach across disciplines and the "ideal is that any faculty member can teach any one of the core courses".[29][f]

Admission

Shimer applicants are evaluated on their academic potential: no minimum grade point average (GPA) or test score is required. The college accepts students who it believes will benefit from and contribute to its intellectual community.[77] Applicants are asked to write an essay analyzing their academic experience, while displaying their creative talents. This, along with a personal interview, is the major criterion for admission.[78] For weekend students, who have typically been out of school for some years, work and prior college experience are also taken into account.[66] Nearly 90 percent of applicants are admitted, but candidates are counseled closely to reduce frivolous applications.[79][80] The average GPA of incoming students is 3.29 on a four point scale.[81] Average composite scores on the ACT and SAT, standardized college admissions tests widely used in the U.S., are 28 (at the 92nd percentile) and 1917 (at the 90th percentile), respectively.[81][82]

Shimer's Early Entrant program, which admits students who have not yet graduated from high school, was first launched in 1950.[29] The program has been supported since then by the Ford Foundation, the Carnegie Foundation and others.[77] Students enter after the 10th or 11th grade (around age 16 or 17), and follow the same curriculum as all other students. The college will consider the application of any interested student, stressing motivation, willingness to learn, and intellectual curiosity as the most important qualifications.[77] Shimer also actively encourages applications from home-schooled students, and makes special accommodations for their credentials (for example, their lack of transcripts).[83] In 2008, 16 percent of new students were early entrants or home-schooled students of a similar age.[84]

In 2009–2010, full-time tuition and fees were $21,000 and on-campus room and board was $12,000. Ninety-one percent of undergraduates received financial aid; the average aid package was $10,594.[3][85]

Recognition and accomplishments

| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| Liberal arts | |

| U.S. News & World Report[86] | NR |

| Washington Monthly[87] | 82 |

In 2009, Shimer was ranked 82nd among liberal arts colleges by Washington Monthly (WM),[88] while it was unranked by U.S. News & World Report (USNWR).[89] In 2006, Shimer was selected as one of the top 50 colleges in All-American Colleges: Top Schools for Conservatives, Old-fashioned Liberals, and People of Faith, which highlights "programs that connect in a special way with the core values of the American founding and the vibrant intellectual traditions of the West".[90] Barron's named Shimer one of the 300 best buys in college education, noting that "the success of the Shimer curriculum depends a great deal on the knowledge and skill of the faculty facilitators, who receive accolades ranging from 'fantastic' to 'brilliant'".[91] In 2000, Insight Magazine named Shimer one of the most politically incorrect schools in the nation, a list which recognized "colleges that had strong and effective traditional curricula that were not obsessed with the recent educational fads and fetishes such as multiculturalism and diversity."[92]

In 2007, Shimer joined a national effort by the Education Conservancy to boycott participation in college-ranking surveys altogether.[93] Then-President William Craig Rice said "what Shimer does well—educating ourselves in on-going dialogue with the greatest minds of the past—can’t be captured in the U.S. News measurements."[94] Nearly all Shimer students take the Graduate Record Exam (GRE), a standardized test for graduate school admissions, their senior year, outscoring three of four potential graduate students and "consistently rank among the best in the nation in scores on the verbal and analytical portions of the test", with average analytic scores in the 91st percentile.[95][96] A 2009 report by The Washington Monthly ranked Shimer third in graduate Ph.D. rate among U.S. liberal arts colleges.[97] In a 1998 study by the University of Wisconsin, Shimer was found to have the highest rate of doctoral productivity of any liberal arts college and the third highest of any undergraduate program in the nation.[95] Studies based on data from the Higher Education Data Sharing Consortium (HEDS) found Shimer to have the seventh-highest Ph.D. productivity rate of all US colleges and universities and the highest rate for Ph.D.s in linguistics.[98][99]

Campus

Shimer relocated to the main campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology in 2006, after 25 years at its former Waukegan, Illinois location, which comprised a loose collection of vintage houses, an old YWCA, and an apartment building.[101][102] Then-president Rice believed that the new location would attract a wider pool of students and financial contributors, and would offer expanded student services (such as dining and athletic facilities) and opportunities to cooperate academically with IIT.[103][104]

The 120-acre (49 ha) campus is centered around 33rd and State Streets, approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) south of the Chicago Loop, in the historic Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago.[105][106] Also known as the Black Metropolis District, the area is a landmark in African-American history for the many notable African-American people and institutions that thrived there in the mid-20th century.[107] The extant structures from that period were added jointly to the National Register of Historic Places in 1986, and were designated a Chicago Landmark in 1998.[108][109]

The campus on which Shimer resides was designed by modernist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, described by the New York Times as "one of the great figures of 20th-century architecture".[110] Van der Rohe's master plan for the IIT campus was one of the most ambitious projects he ever conceived and the campus, with 20 of his works, is the greatest concentration of his buildings in the world.[111] The campus was landscaped by van der Rohe's close colleague Alfred Caldwell, one the last representatives of the Prairie School of landscape architects.[112][113] In 1976, the American Institute of Architects named the IIT campus one of the 200 most significant works of architecture in the United States.[114] The IIT Main Campus was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2005.[115]

Shimer occupies 17,000 square feet (1,600 m2) on the first and second floors of what was formerly the Institute of Gas Technology complex, under a long-term lease agreement with IIT.[35] The complex, designed by van der Rohe, consists of four buildings built between 1947 and 1955. The South building was home to the first industrial nuclear reactor in the U.S.[100]

Shimer students who choose to live on-campus reside in Gunsaulus Hall, which was converted into a fully furnished apartment-style residence in 2008.[117][118] Shimer has access to the resources of the Paul V. Galvin Library, IIT's main research library, which contains 1.8 million volumes, more than 25,500 journal titles, and a wide range of digital resources.[119] Shimer's own collection of 15,000 books is also housed in the Galvin library, where it was moved when the school relocated from Waukegan.[120]

Other facilities available to Shimer students include the McCormick Tribune Campus Center (MTCC), which was designed by internationally acclaimed architect Rem Koolhaas in 2003.[116][121] The facility is the main student activity center, with food courts, a newsstand, lounge areas, conference centers, computer workstations, a bookstore, and an auditorium.[121] Students may also take advantage of the Keating Sports Center, the main athletic complex and home to IIT's varsity teams. The center offers racquetball courts, bowling, rock climbing, and a wide range of dance and exercise classes along with basketball, volleyball, soccer and other team sports.[122]

Governance

Shimer College is a not-for-profit corporation with a self-perpetuating Board of Trustees responsible for the affairs and the assets of the college. The board delegates authority to the president of the college, who acts as the chief executive administrator, and to the dean of the college and the faculty regarding academic affairs.[123] As of December 2009, the board had 36 members (including three students and two faculty), with a target membership of 40, and was chaired by Christopher B. Nelson, president of St. John's College.[124]

"As a function of its mission to promote active citizenship", Shimer states that it is "devoted to internal self-governance to an extent that is rare among institutions of higher education."[5] Since 1977, Shimer has been governed internally by a deliberative body called the Assembly. Students and faculty are elected by the community at large to serve on all administrative bodies, including the Board of Trustees, such that "all the top-down bureaucracy of traditional colleges and universities has been replaced by participatory democracy committed to dialogue."[125] The Assembly has no legal authority, but governs, Shimer states, "by virtue of the moral suasion established by communal deliberation".[126] Begun informally in the years immediately prior to the move to Waukegan, the Assembly was formalized by a constitution in 1980.[127] Voting members include all students, faculty, administrators, staff and trustees.[128] Alumni are also members but do not vote. The Assembly advises the administration and conducts the business of the college through a system of committees with purview over administration, academic planning, budgeting, admissions, grievances, financial aid, and quality of life. Committees are composed of faculty, staff, and students elected by the Assembly as a whole.[129]

Shimer students are also represented on, and free to participate in, the IIT Student Government Association (SGA), which acts as a liaison to the university administration and a forum for express student opinion.[130][131]

Student life

The New York Times has called Shimer "one of the smallest liberal arts colleges in the United States", and described Shimer students as "... both valedictorians and high school dropouts. What the students share, besides a love of books, is a disdain for the conventional style of education. Many say they did not have a good high school experience."[132] Students tend to be individualistic, creative thinkers, and are encouraged to be questioning and inquisitive.[133] Shimer enrolled 100 students in 2009, from 22 states and 2 other countries; the majority came from Illinois.[75] Over 80 percent of the students were white and 40 percent were over age 25.[3] Of full-time students who attend their first year, 70 percent return for their second. Fifty-five percent of first-time, full-time students will graduate within six years.[3]

Fraternities, sororities and other organizations that promote exclusivity are not allowed and Shimer has no organized clubs or athletic programs of its own.[134] The college has a tradition of community meals, which all are invited to attend, that dates back to the early days on the Waukegan campus, when the whole community would meet for potluck meals and discuss matters of general interest in gatherings that eventually gave birth to the Assembly.[127] The Orange Horse, Shimer's bi-annual talent show, is a tradition dating back to the 1960s and invites students, faculty, and alumni to read poetry, sing, play music, or tell jokes, individually or in groups.[135]

The Shimer theater program has been under the direction of Humanities Professor Eileen Buchanan since 1967. Buchanan, also a professional actor and director, directs productions that complement the curriculum and offer anyone who wants to participate in theater the chance to do so.[136] Productions in the Chicago location have included Anton Chekhov's Uncle Vanya and Eve Ensler's Vagina Monologues.[137][138]

In addition to the resources of the MTCC and the athletic facilities, Shimer students are able to take part in the more than 150 student organizations sponsored by IIT, including Liit Magazine, the student-run literary magazine of IIT, and IIT's on-campus radio station, WIIT, where they can host their own shows.[139][140]

Shimer students do not necessarily graduate with specific career skills.[95] Most students go on to graduate studies: 50 percent of Shimer graduates earn master's degrees and 21 percent go on to earn doctorates.[96][141] Another 10 percent attend law school and 5 percent go to business school.[91]

Alumni

As of 2008, Shimer claimed 5,615 living alumni.[2] Nearly 25 percent of graduates are employed in education (from elementary schools through college), 7 percent are lawyers, and 7 percent work in computer software. The remainder occupy all walks of life, from consulting to social services, to non-profit organizations.[66]

Samuel W. McCall, a US Representative from Massachusetts's 8th congressional district and later Governor of Massachusetts, attended the Mt. Carroll Seminary in the 1860s.[142] Shimer graduates include poets and authors such as Peter Cooley, who has sponsored a Shimer College poetry contest for many years, as part of the University and College Poetry Prize Program of the Academy of American Poets; poet Stephen Dobyns; Pulitzer Prize-nominated writer John Norman Maclean, author of the bestselling Fire on the Mountain; and award-winning comic book writer and editor Catherine "Cat" Yronwode.[143] Alumni also include notable political theorists such as Arab-Israeli conflict scholar Alan Dowty and Robert Keohane, author of the seminal work After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy, and political activists such as C. Clark Kissinger, former National Secretary of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and situationist Ken Knabb.[144] Computer pioneers Nick Pippenger and Daniel J. Sandin went to Shimer, as did experimental artists Laurie Spiegel and Ken Friedman.[145]

Other notable alumni include singer/songwriter Phoebe Snow; medical inventor, Slate columnist, and Yale University School of Medicine professor Sydney Spiesel; Whitman College Classics professor Elizabeth Vandiver; author, activist, and internet publisher Heather Corinna; computer software author Steve Heller; philosopher and chess Grandmaster Jesse Kraai; and Florida State Representative Ron Schultz.[146] Chicago businessman and Shimer graduate Peter Hanig co-organized the international public art exhibit CowParade in 1999.[147]

Notes

^ a: The school was called a seminary but did not engage in religious instruction. It was part finishing school and part preparatory school, designed to produce female teachers.[148] The four-year program (which the Junior College later extended to six) covered what was essentially a good quality high school program, such that "students [were] prepared for the very best institutions east and west."[149]

^ b: Under the agreement, Shimer remained independent with its own board, of which a majority represented the U. of C. and two-thirds were required to be Baptist. Shimer was administered locally, but subject to a chief administrator in Chicago for final decisions.[150]

^ c: The others are St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland, and Santa Fe, New Mexico, Thomas Aquinas College in Santa Paula, California, and Thomas More College of Liberal Arts in Merrimack, New Hampshire.[132]

^ d: Adler and Hutchins collaborated on The Great Books of the Western World, published in 1952, which was intended to present the entire Western canon in one 54-volume set.[151] The selection of works it contained defined the reading list on which Great Books curricula were based, and which Shimer has largely kept, with minor changes, ever since.

^ e: The Hutchins plan also instituted placement exams, which students would take before enrollment "to determine how much or how little of the program they need".[152] This practice lives on at Shimer, where students are able to place out of several of the basic core courses by examination.[153]

^ f: This aspirational goal is very rarely achieved. Professor David Shiner, who joined the faculty in 1977, received special recognition from the college in 1998 for the "unique distinction of having taught the entire core curriculum".[154]

References

- ^ "Shimer College". Carnegie Classifications. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Retrieved 2010–07–06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "Shimer College Profile" (PDF). R.H. Perry & Associates. p. 6. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Grossman, Ron (2010–01–27). "Shimer College in Power Struggle" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2010–05–05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Shimer College Catalog 2009, p. 30.

- ^ Bonham 1883, p. 219.

- ^ Society for the Advancement of Education (1936). School and Society. 43: 873. ISSN 0036-6455.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b "An Act to Incorporate the Mount Carroll Seminary". Laws of the State of Illinois Enacted by the General Assembly. 1: 13. 1867. OCLC 38559494.

- ^ History of Carroll County 1878, p. 344.

- ^ Bonham 1883, p. 207.

- ^ History of Carroll County 1878, pp. 348–349.

- ^ "Annual Register; July 1897 – July 1898". 18–19. Chicago: The University of Chicago. 1898: 139. OCLC 2068936.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Eells, Walter Crosby; Bogue, Jesse Parker, eds. (1952). American Junior Colleges. Washington, D.C.: American Council on Education. p. 203. ISSN 0065-9029.

- ^ Tinling, Marion (1986). Women Remembered: A Guide to Landmarks of Women's History in the United States. New York: Greenwood Press. p. 486. ISBN 0313239843.

- ^ Davis, Wayne (1939). How to Choose a Junior College: A Directory for Students, Parents, and Educators. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 100. OCLC 4803155.

- ^ Gage, Harry Morehouse, ed. (1920). "Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Annual Meeting of the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools". North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools: 57. OCLC 1607454.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Moorhead 1983, p. 64.

- ^ Moorhead 1983, p. 110.

- ^ Moorhead 1983, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Episcopal Church General Convention (1963). The Episcopalian. 128. New York: Church Magazine Advisory Board: 37. ISSN 0013-9629.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stem, George G. (1963). "Characteristics of the Intellectual Climate in College Environments". Harvard Educational Review. XXXIII. Harvard University Graduate School of Education: 5–41. ISSN 0017-8055.

- ^ a b Jencks, Christopher; Reisman, David (April 1966). "From the Academic Revolution: Shimer College". Phi Delta Kappan. 47 (8). Phi Delta Kappa International: 416. ISSN 0031-7217.

- ^ Moorhead 1983, p. 144.

- ^ Severson 1975, p. 13.

- ^ Severson 1975, p. 14.

- ^ Maclean, John (1974–12–24). "Shimer: A Small Place But Loved" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2010–05–05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Unger, Robert (1977–11–28). "Tiny Shimer College Gets Bill Extension" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2010–05–08.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Moorhead 1983, p. 196.

- ^ a b c d Henderson, Harold (1988–06–16). "Big Ideas; Tiny Shimer College Has Survived For 135 Years On Great Books, High Hopes, And Very Little Money". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2010–05–06.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Schilling, Thomas (1982–06–29). "Tiny College Gets Growing Pains After Move to Waukegan" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2010–05–06.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Moorhead 1983, p. 199.

- ^ a b Golab, Art (1995–12–11). "Long Road to Rebirth at Shimer College; New Quarters, Old Curriculum Spell Success" (fee required). Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2010–05–06.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Shimer College". Higher Learning Commission. Retrieved 2010–04–21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "College Celebrates Move to Chicago" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. 2006–10–09. Retrieved 2010–05–06.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Epstein, David (2006–01–23). "Great Books and City Lights". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 2010–04–23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Isaacs, Deanna (2010–02–25). "Who's Buying Shimer?". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2010–05–06.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Troop, Don (2010–02–25). "At a Tiny College, an Epic Battle Over Academic Authority". Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 2010–05–06.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Paquette, Ron (2010–04–30). "The Cave-Dwellers of Shimer". Minding the Campus. Retrieved 2010–11–19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Goldstein, Linda (2010–02–23). "Shimer Students Protest Outside Their Board of Trustees Meeting". IIT TechNews. Retrieved 2011–05–10.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Troop, Don (2010–04–20). "Shimer College Ousts Its President". Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 2010–05–06.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Ritter, Jim (2006–10–06). "A Bachelor's in Books?: Shimer College Brings Great Books Curriculum to City" (fee required). Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2010–04–25.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Casement 1996, p. 34.

- ^ Mayer, Milton (1946–10–28). "Great Books". Life: 2–7. ISSN 0024-3019.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Adler, Mortimer J. (1982). The Paideia Proposal: An Educational Manifesto. New York: Touchstone. p. 32. ISBN 0684841886.

- ^ Beam 2008, pp. 41–43.

- ^ "Robert Maynard Hutchins". University of Chicago. Retrieved 2010–04–25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Wilcox, Clifford (2006). Robert Redfield and the Development of American Anthropology (1st paperback ed.). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. pp. 79, 101. ISBN 0739117777.

- ^ a b Kavaloski 1979, p. 235.

- ^ Hutchins, Robert Maynard (1952). The Great Conversation: The Substance of Liberal Education. Great Books of the Western World. Vol. 1. Chicago: Encyclopedia Britannica. p. xiv. ISBN 0852291639.

- ^ a b Casement 1996, p. 89.

- ^ Shimer College Catalog 2009, pp. 17–18.

- ^ "Shimer College Spring Registration for IIT/VanderCook Students". IIT Today. Illinois Institute of Technology. 2007–11–19. Retrieved 2010–07–07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b c Mullaney, Kathleen. "Shimer College: Reflections on Teaching a Structured Four Year Curriculum". National Great Books Curriculum. Retrieved 2010–07–07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Isaacs, Deanna (2007–08–30). "So Long, Shimer". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2010–05–01.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Humanities Courses". Shimer College. Retrieved 2010–04–23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Social Science Courses". Shimer College. Retrieved 2010–05–01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Moon, Don. "Natural Sciences at Shimer". Shimer College. Retrieved 2010–05–01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Integrative Studies Courses". Shimer College. Retrieved 2010–05–01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c Shimer College Catalog 2009, p. 21.

- ^ Wood, Deborah Leigh (1981–11–29). "Weekends Made for College" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2010–05–05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Weekend Program". Shimer College. Retrieved 2011–02–22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "The Shimer Experience: 1995–1997 Catalogue". Shimer College. Archived from the original on 1997–07–13. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|archivedate=(help) - ^ "Living for the Weekend College". Chicago Tribune. 2010–05–06. Retrieved 2010–05–06.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Colleges: Unknown, Unsung & Unusual". Time. 1963–04–19. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Shimer-at-Oxford". The Living Church. 155: 6. 1967. OCLC 17345342.

- ^ a b c Peterson's Four-Year Colleges. Lawrenceville, NJ: Thompson/Peterson's. 2006. p. 2249. ISBN 0768921538.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editions=ignored (help) - ^ "Shimer-in-Oxford" (PDF). Shimer College. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Shimer-in-Oxford Program". Shimer College. Retrieved 2011–02–22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Shimer College Catalog 2009, p. 29.

- ^ E. D. Hirsch Jr. (1987). Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0394758439.

- ^ "Learn About Us". The Core Knowledge Foundation. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Jaschik, Scott (2008–08–25). "Will More Colleges Merge?". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 2010–07–07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Carlson, Scott (1999–11–19). "A Campus Revival for the Great Books". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 2010–06–05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Dual Admissions at HWC". Harold Washington College. Retrieved 2010–05–06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c Peterson's Colleges in the Midwest. Lawrenceville, New Jersey: Peterson's. 2009. p. 61. ISBN 0768926904.

- ^ "Quick Facts". Shimer College. Retrieved 2010–04–21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c Complete Book of Colleges 2005 (revised ed.). New York: Princeton Review. 2004. p. 1335. ISBN 0375764062.

- ^ "Admission & Finance". Shimer College. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Shimer College". Best Colleges 2010. US News & World Report. Retrieved 2010–04–25.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Asher, Donald (2007). Cool Colleges: For the Hyper-Intelligent, Self-Directed, Late-Blooming and Just Plain Different (2nd ed.). Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. p. 22. ISBN 1580088392.

- ^ a b "Shimer College". CollegeData. Retrieved 2010–06–01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ For ACT percentile: "ACT High School Profile Report" (PDF). ACT. p. 10. Retrieved 2010–02–23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help). For SAT percentile: "SAT Percentile Ranks for Males, Females and Total Group" (PDF). CollegeBoard. Retrieved 2010–05–12.{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Dennis, Jeanne Gowen (2004). Homeschooling High School: Planning Ahead for College Admission. Lynwood, WA: Emerald Books. p. 244. ISBN 1932096116.

- ^ "Entering Class by the Numbers" (PDF). Symposium. Shimer College. Fall 2008. p. 2. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Peterson's College Money Handbook 2009 (26th ed.). Lawrenceville, NJ: Peterson's. 2008. pp. 448–449. ISBN 0768926254.

- ^ "2024-2025 National Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "The Washington Monthly Liberal Arts Rankings". The Washington Monthly. 2009. Retrieved 2009–12–20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". America's Best Colleges 2009. U.S. News & World Report. 2009. Retrieved 2009–05–18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ All-American Colleges: Top Schools for Conservatives, Old-Fashioned Liberals, and People of Faith. Wilmington, Delaware: Intercollegiate Studies Institute. 2006. ISBN 71849223.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ a b Barron's Best Buys In College Education (7th ed.). Hauppauge, New York: Barrons Educational Series. 2002. pp. 132–134. ISBN 0764120182.

- ^ Hussain, Rummana (2000–09–28). "Shimer College Proud of Non-P.C. Rating". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2010–04–24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Presidents' Letter". The Education Conservancy. 2007–05–10. Retrieved 2010–05–24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Shimer College Joins Anti-Rankings Effort". Shimer College. Retrieved 2010–04–24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c Sweeney, Annie (2000–10–03). "Magazine Lauds Shimer College" (fee required). Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2010–04–27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Flink, John (1998–01–26). "Small Shimer College Ranks High in Sending Students on to Ph.D.s" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2010–04–23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Liberal Arts College Rankings". The Washington Monthly. Retrieved 2010–05–05.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help) - ^ Bourque, Susan C. (1999). "Reassessing Research: Liberal Arts Colleges and the Social Sciences". Daedalus. 28 (1): 265. Retrieved 2010–04–27.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Where Linguistics PhDs Received their Undergraduate Degrees". Inside College. Inside College. Retrieved 2010–04–25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "Buildings – past and present, extant and non-extant – known to have been used by Illinois Institute of Technology (Chicago), 1940–2010". Illinois Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2011–05–10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Moran, Dan (2003–05–17). "Celebrating Shimer" (fee required). The Waukegan News-Sun. Retrieved 2010–05–04.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "College Celebrates Move to Chicago" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. 2006–09–06. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Shimer College OKs Move to IIT campus" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. 2006–01–20. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Bell, Barbara (2005–11–23). "Struggling College May Move; Shimer Considers Relocating To IIT" (fee required). Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "IIT History – Inventing the Future". Illinois Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Visitor Information". Illinois Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Excerpt from the National Register Nomination for Chicago's Black Metropolis". National Park Service. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Black Metropolis Thematic Nomination (PDF), National Park Service, 1985–11–07, retrieved 2010–04–22

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "City Council Approves "Black Renaissance" Literary Landmarks". City of Chicago. Retrieved 2011–05–10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Mies van der Rohe Dies at 83; Leader of Modern Architecture". The New York Times. 1969–08–19. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Mies at IIT". Illinois Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2011–05–10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Domer, Dennis. "The Last Master" (PDF). Inland Architect Magazine: 69. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Alfred Caldwell". Illinois Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Schweiterman, Joseph P; Caspall, Dana M; Heron, Jane (2006). The Politics Of Place: A History of Zoning in Chicago. Chicago, IL: Lake Claremont Press. p. 51. ISBN 1893121267.

- ^ National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Illinois Institute of Technology Academic Campus (PDF), National Park Service, 2005–08–12, retrieved 2010–04–22

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Reed, Cheryl (2003–10–01). "IIT Architect Would Love Encore; Designer Of Student Center Would Like To Build High-Rise Here" (fee required). Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2010–04–23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Housing Choices for Current Gunsaulus Hall Residents". Illinois Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Gunsaulus Hall". Illinois Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "IIT Libraries 2007" (PDF). Illinois Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Pagelow, Ryan (2007–01–11). "Mega Book Sale; Shimer Moves Library to Chicago Campus, Selling 10,000 Books; Get-Out-Of-Town Sale" (fee required). The Waukegan News Sun. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Why Architecture Matters: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2002. p. 178. ISBN 0226423212.

{{cite book}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Text "last – Kamin" ignored (help) - ^ "Intramurals and Recreation". Illinois Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2011–05–10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Shimer College Catalog 2009, p. 31.

- ^ Isaacs, Deanna (2009–12–10). "The Conservative Menace". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2010–04–23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Kavaloski 1979, p. 243.

- ^ Constitution of the Assembly 2008, p. 2.

- ^ a b Shiner, David; Wikse, Jack. "On Not Knowing the Particulars: The Mission of the Assembly". Promulgates. 7 (1). Archived from the original on 2001–10–30. Retrieved 2010–04–23.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|archivedate=(help) - ^ Feldman, Sam (2010–04–03). "Big Trouble at Little Shimer: What's Happening to Chicago's Great Books College?". Chicago Weekly. Retrieved 2010–07–07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Constitution of the Assembly 2008, pp. 9–11.

- ^ "Bylaws of the Student Government Association of Illinois Institute of Technology". Student Government Association of Illinois Institute of Technology. 2009–09–22. pp. 11–12. Retrieved 2010–04–27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "About". Student Government Association of Illinois Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2011–05–10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Johnson, Dirk (2007–11–04). "Small Campus, Big Books". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010–05–22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Peterson's Four-Year Colleges 2007. Lawrenceville, New Jersey: Thompson Peterson's. 2006. p. 2248. ISBN 0768921538.

- ^ "Student Life". Shimer College. Retrieved 2010–04–21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Orange Horse" (PDF). Shimer College. 2008–11–15. Retrieved 2010–04–27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Eileen Powers Buchanan, Professor of Humanities". Shimer College. Retrieved 2010–04–21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^

"Spring Theater – Uncle Vanya". Shimer College. Retrieved 2010–04–27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Shimer College Theater to Present "The Vagina Monologues"". IIT Today. Illinois Institute of Technology. 2006–10–17. Retrieved 2010–04–27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Liit Literary Magazine". IIT Today. Illinois Institute of Technology. 2010–04–01. Retrieved 2010–04–27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Shimer the Great Books College of Chicago" (PDF). Shimer College. p. 13. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Southwell, David (1998–01–23). "Shimer College's Graduates Go Far" (fee required). Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2010–04–21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "McCall, Samuel Walker, (1851–1923)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved 2010–05–13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ References in order of mention:

- "Rites, Masks, Light and the Poet's Craft: An Interview with Peter Cooley". The Southern Quarterly. 23: 77. 1984. ISSN 0038-4496.

- "Stephen Dobyns". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "About John Maclean". John Maclean Books. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "Cat Yronwode". Catherine Yronwode. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

- ^ References in order of mention:

- "Alan Dowty". Middle East Strategy at Harvard. Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Gourevitch, Peter A. (1999–09–01). "Robert O. Keohane: The Study of International Relations" (fee required). PS: Political Science and Politics. Retrieved 2010–05–10.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - Sale, Kirkpatrick (1973). SDS. New York: Vintage Books. p. 56. ISBN 0394719654.

- Knabb, Ken (1997). Public Secrets: Collected Skirmishes of Ken Knabb. Bureau of Public Secrets. p. 93. ISBN 0939682036.

- "Alan Dowty". Middle East Strategy at Harvard. Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

- ^ References in order of mention:

- "Nicholas Pippenger". Harvey Mudd College. Retrieved 2010–04–25.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "Daniel J. Sandin". Media Arts Fellowships. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "The Register of Ken Friedman Collection 1964–1971". University of California San Diego. Retrieved 2010–05–23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Bosse, Joanne (1997). "Creating Options, Creating Music: An Interview with Laurie Spiegel". Contemporary Music Review. 12 (1 & 2): 81–87. ISSN 0749446.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check|issn=value (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

- "Nicholas Pippenger". Harvey Mudd College. Retrieved 2010–04–25.

- ^ References in order of mention:

- Jerome, Jim (1976–03–22). "Named for a Train, Phoebe Snow Is on the Right Track with a Second Hit Album". People. 5 (11). Retrieved 2010–09–09.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - "Who We Are". Slate Magazine. Washington Post.Newsweek Interactive. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "The Faculty". Whitman College. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "The Scarleteen Staff & Volunteers". Scarleteen. Retrieved 2010–05–13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "Steve Heller's Home Page". Chrysalis Software Corporation. Retrieved 2010–04–22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "Jesse Kraai". Washington Times. Retrieved 2011–05–10.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "Representative Ron Schultz". Florida House of Representatives. Retrieved 2010–04–28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

- Jerome, Jim (1976–03–22). "Named for a Train, Phoebe Snow Is on the Right Track with a Second Hit Album". People. 5 (11). Retrieved 2010–09–09.

- ^ Nevala, Amy E. (2003–04–30). "Shimer's Novel Curriculum; Waukegan Liberal Arts College Teaches Students 'How To Think' With More Than 200 Classic Texts". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2010–06–28.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Cubbage 2009, p. 91.

- ^ Bateman, Newton; Selby, Paul; Hostetter, Charles L., eds. (1913). "The Frances Shimer School of the University of Chicago". Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois and History of Carroll County. Vol. II. Chicago: Munsell Pub. Co. p. 717. OCLC 1745414.

- ^ Moorhead 1983, p. 47.

- ^ Mayer, Milton S. (1993). Robert Maynard Hutchins: A Memoir. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 297. ISBN 052007091.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Smith, Jesse Alan (1953). Chicago's Left Bank. Chicago: H. Regnery Co. p. 236. OCLC 1072972.

- ^ Shimer College Catalog 2009, p. 15.

- ^ "David Shiner, Professor of Humanities and the History of Ideas". Shimer College. Retrieved 2010–05–10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

Works cited

- Beam, Alex (2008). A Great Idea at the Time: The Rise, Fall, and Curious Afterlife of the Great Books (1st ed.). New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 1586484877.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bonham, Jeriah (1883). Fifty Years' Recollections: With Observations and Reflections on Historical Events, Giving Sketches of Eminent Citizens Their Lives and Public Services. Peoria, Ill.: J.W. Franks & Sons. OCLC 3262599.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Casement, William (1996). The Great Canon Controversy: The Battle of the Books in Higher Education. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1557787425.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - H.F. Kett & Co, ed. (1878). The History Of Carroll County, Illinois, Containing a History of the County—Its Cities, Towns, Etc. Chicago: H.F. Kett & Co. OCLC 3368934.

- Cubbage, Kent Thomas (2009). America's Great Books Colleges and Their Curious Histories of Success, Struggle, and Failure (Ph.D. thesis). University of South Carolina.

{{cite thesis}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kavaloski, Vincent C. (1979). "Interdisciplinary Education and Humanistic Aspiration: A Critical Reflection". In Kockelmans, Joseph J (ed.). Interdisciplinarity and Higher Education. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 224–243. ISBN 0271023260.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Moorhead, Patrick H. (1983). Shimer College Presidency 1930 to 1980 (Ed.D. thesis). Loyola University of Chicago. OCLC 9789513.

{{cite thesis}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Malmkus, Doris (2003). "Frances Wood Shimer, Cindarella Gregory, and the 1853 founding of Shimer College". Journal of Illinois History. 6. Illinois Historic Preservation Agency: 195–214. ISSN 1522-0532.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Severson, Stanley (1975). Responses to Threatened Organizational Death (Ph.D. thesis). University of Chicago. OCLC 28780062.

{{cite thesis}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Constitution of the Assembly of Shimer College" (PDF). Shimer College. 2008. Retrieved 2010–04–23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Frances Wood Shimer, 1826–1901. Mt. Carroll, Ill.: Shimer College. 1901. OCLC 13863166.

- "Shimer College Catalog 2009–2011" (fee required). Shimer College. 2009. Retrieved 2010–06–29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

External links