Aesop: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

The Greek fabulist '''Aesop''' or '''Esop''' (pronounced {{IPA-en|ˈeɪsɒp|}} {{respell|AY|sop}} or {{IPA-en|ˈiːsəp|}} {{respell|EE|səp}}, {{lang-el|Αἴσωπος}}, ''Aisōpos'') is given the dates c. 620-564 BCE and was by tradition born a [[Slavery in Ancient Greece|slave]] (''δοῦλος''). Although known for the [[Aesop's Fables|fables ascribed to him]], Aesop's existence remains uncertain and no writings by him survive. Numerous fables appearing under his name were gathered across the centuries and in many languages in a storytelling tradition that continues to this day. In many of these tales animals speak and have human characteristics. |

The Greek fabulist '''Aesop''' or '''Esop''' (pronounced {{IPA-en|ˈeɪsɒp|}} {{respell|AY|sop}} or {{IPA-en|ˈiːsəp|}} {{respell|EE|səp}}, {{lang-el|Αἴσωπος}}, ''Aisōpos'') is given the dates c. 620-564 BCE and was by tradition born a [[Slavery in Ancient Greece|slave]] (''δοῦλος''). Although known for the [[Aesop's Fables|fables ascribed to him]], Aesop's existence remains uncertain and no writings by him survive. Numerous fables appearing under his name were gathered across the centuries and in many languages in a storytelling tradition that continues to this day. In many of these tales animals speak and have human characteristics. |

||

Scattered details of Aesop's life can be found in ancient sources, including [[Aristotle]], [[Herodotus]], and [[Plutarch]]. An ancient literary work called ''The Aesop Romance'' tells an episodic, probably highly fictional version of his life, including the traditional description of Aesop as a strikingly ugly slave who by his cleverness acquires freedom and becomes an adviser to kings and city-states |

Scattered details of Aesop's life can be found in ancient sources, including [[Aristotle]], [[Herodotus]], and [[Plutarch]]. An ancient literary work called ''The Aesop Romance'' tells an episodic, probably highly fictional version of his life, including the traditional description of Aesop as a strikingly ugly slave who by his cleverness acquires freedom and becomes an adviser to kings and city-states. Depictions of Aesop in popular culture over the last 2500 years have included several works of art and his appearance as a character in numerous books, films, plays, and television programs. |

||

==Life== |

==Life== |

||

Revision as of 17:48, 14 May 2011

The Greek fabulist Aesop or Esop (pronounced /ˈeɪsɒp/ AY-sop or /ˈiːsəp/ EE-səp, Template:Lang-el, Aisōpos) is given the dates c. 620-564 BCE and was by tradition born a slave (δοῦλος). Although known for the fables ascribed to him, Aesop's existence remains uncertain and no writings by him survive. Numerous fables appearing under his name were gathered across the centuries and in many languages in a storytelling tradition that continues to this day. In many of these tales animals speak and have human characteristics.

Scattered details of Aesop's life can be found in ancient sources, including Aristotle, Herodotus, and Plutarch. An ancient literary work called The Aesop Romance tells an episodic, probably highly fictional version of his life, including the traditional description of Aesop as a strikingly ugly slave who by his cleverness acquires freedom and becomes an adviser to kings and city-states. Depictions of Aesop in popular culture over the last 2500 years have included several works of art and his appearance as a character in numerous books, films, plays, and television programs.

Life

"The name of Aesop is as widely known as any that has come down from Graeco-Roman antiquity [yet] it is far from certain whether a historical Aesop ever existed", writes one scholar; "in the latter part of the fifth century [BCE] something like a coherent Aesop legend appears, and Samos seems to be its home."[1]

The earliest Greek sources, including Aristotle, indicate that Aesop was born around 620 BCE in Thrace at a site on the Black Sea coast which would later become the city Mesembria; a number of later writers from the Roman imperial period (including Phaedrus, who adapted the fables into Latin), say that he was born in Phrygia.[2] The 3rd-century poet Callimachus called him "Aesop of Sardis,"[3] and the later writer Maximus of Tyre called him "the sage of Lydia."[4]

From Aristotle[5] and Herodotus[6] we learn that Aesop was a slave in Samos and that his masters were first a man named Xanthus and then a man named Iadmon; that he must eventually have been freed, because he argued as an advocate for a wealthy Samian; and that he met his end in the city of Delphi. Plutarch[7] tells us that Aesop had come to Delphi on a diplomatic mission from King Croesus of Lydia, that he insulted the Delphians, was sentenced to death on a trumped-up charge of temple theft, and was thrown from a cliff (after which the Delphians suffered pestilence and famine); before this fatal episode, Aesop met with Periander of Corinth, where Plutarch has him dining with the Seven Sages of Greece, sitting beside his friend Solon, whom he had met in Sardis. (Leslie Kurke suggests that Aesop himself "was a popular contender for inclusion" in the list of Seven Sages.[8])

Problems of chronological reconciliation dating the death of Aesop and the reign of Croesus led the Aesop scholar (and compiler of the Perry Index) Ben Edwin Perry in 1965 to conclude that "everything in the ancient testimony about Aesop that pertains to his associations with either Croesus or with any of the so-called Seven Wise Men of Greece must be reckoned as literary fiction," and Perry likewise dismissed Aesop's death in Delphi as legendary;[9] but subsequent research has established that a possible diplomatic mission for Croesus and a visit to Periander "are consistent with the year of Aesop's death."[10] Still problematic is the story by Phaedrus which has Aesop in Athens, telling the fable of the frogs who asked for a king, during the reign of Peisistratos, which occurred decades after the presumed date of Aesop's death.[11]

The Aesop Romance

Along with the scattered references in the ancient sources regarding the life and death of Aesop, there is a highly fictional biography now commonly called The Aesop Romance (also known as the Vita or The Life of Aesop or The Book of Xanthus the Philosopher and Aesop His Slave), "an anonymous work of Greek popular literature composed around the second century of our era....Like The Alexander Romance, The Aesop Romance became a folkbook, a work that belonged to no one, and the occasional writer felt free to modify as it might suit him."[12] Multiple, sometimes contradictory, versions of this work exist. The earliest known version "was probably composed in the 1st century CE", but the story "probably circulated in different versions for centuries before it was committed to writing";[13] "certain elements can be shown to originate in the 4th century BCE."[14] Scholars long dismissed any historical or biographical validity in The Aesop Romance; widespread study of the work began only toward the end of the 20th century.

In The Aesop Romance, Aesop is a slave of Phrygian origin on the island of Samos, and extremely ugly. At first he lacks the power of speech, but after showing kindness to a priestess of Isis, is granted by the goddess not only speech but a gift for clever storytelling, which he uses alternately to assist and confound his master, Xanthus, embarrassing the philosopher in front of his students and even sleeping with his wife. After interpreting a portent for the people of Samos, Aesop is given his freedom and acts as an emissary between the Samians and King Croesus. Later he travels to the courts of (the imaginary) Lycurgus of Babylon and Nectanabo of Egypt in a section that appears to borrow heavily from the romance of Ahiqar.[15] The story ends with Aesop's journey to Delphi, where he angers the citizens by telling insulting fables, is sentenced to death and, after cursing the people of Delphi, throws himself from a cliff.

Aesop the fabulist

Though Aesop became famous across the ancient world as the preeminent teller of fables, he did not create the genre; the earliest known story with talking animals in ancient Greek is the fable of the Hawk and the Nightingale found in the work of Hesiod, who lived some three centuries before Aesop.

Aesop may or may not have written his fables - The Aesop Romance claims that he wrote them down and deposited them in the library of Croesus; Herodotus calls Aesop a "writer of fables" and Aristophanes speaks of "reading" Aesop[16] - but no writings by Aesop have survived. Scholars speculate that "there probably existed in the fifth century [BCE] a written book containing various fables of Aesop, set in a biographical framework."[17] True or not, by the time of Classical Greece Aesop and the fables attributed to him seem to have been widely known. Sophocles in a poem addressed to Euripides made reference to Aesop's fable of the North Wind and the Sun.[18] Socrates while in prison turned some of the fables into verse,[19] of which Diogenes Laertius records a small fragment.[20] The early Roman playwright and poet Ennius also rendered at least one of Aesop's fables in Latin verse, of which the last two lines still exist.[21]

The body of work identified as Aesop's Fables was transmitted by a series of authors writing in both Greek and Latin. Demetrius of Phalerum made a collection in ten books, probably in prose (Αισοπείων α) for the use of orators, which has been lost.[22] Next appeared an edition in elegiac verse, cited by the Suda, but the author's name is unknown. Phaedrus, a freedman of Augustus, rendered the fables into Latin in the first century CE. At about the same time Babrius turned the fables into Greek choliambics. A 3rd century author, Titianus is said to have rendered the fables into prose in a work now lost.[23] Avianus (of uncertain date, perhaps the 4th century) translated 42 of the fables into Latin elegiacs. The 4th century grammarian Dositheus Magister also made a collection of Aesop's Fables, now lost.

Aesop's Fables continued to be revised and translated through the ensuing centuries, with the addition of material from other cultures, so that the body of fables known today bears little relation to those Aesop originally told. With a surge in scholarly interest beginning toward the end of the 20th century, some attempt has been made to determine the nature and content of the very earliest fables which may be most closely linked to the historic Aesop.[24]

Physical appearance and the question of African origin

The anonymously authored Aesop Romance (usually dated to the 1st or 2nd century CE; see above) begins with a vivid description of Aesop's appearance, saying he was "of loathsome aspect...potbellied, misshapen of head, snub-nosed, swarthy, dwarfish, bandy-legged, short-armed, squint-eyed, liver-lipped—a portentous monstrosity,"[25] or as another translation has it, "a faulty creation of Prometheus when half-asleep."[26] The earliest text by a known author that refers to Aesop's appearance is Himerius in the 4th century, who says that Aesop "was laughed at and made fun of, not because of some of his tales but on account of his looks and the sound of his voice."[27] The evidence from both of these sources is dubious, since Himerius lived some 800 years after Aesop and his image of Aesop may have come from The Aesop Romance, which is essentially fiction; but whether based on fact or not, at some point the idea of an ugly, even deformed Aesop took hold in popular imagination. Scholars have begun to examine why and how this "physiognomic tradition" developed.[28]

Ancient sources mention two famous statues of Aesop, one by Aristodemus [citation needed] and another by Lysippus which was in a place of honor before the Seven Sages of Greece, and Philostratus describes a painting of Aesop surrounded by the animals of his fables.[29] Unfortunately, none of these works seem to have survived.

Another, much later tradition depicts Aesop as a black African from Ethiopia.[30] The presence of such slaves in Greek-speaking areas is suggested by the fable "Washing the Ethiopian white" that is ascribed to Aesop himself. This concerns a man who buys a black slave and, assuming that he was neglected by his former master, tries very hard to wash the blackness away. But nowhere in the fable is it suggested that this constitutes a personal reference. The first known promulgator of the idea was Planudes, a Byzantine scholar of the 13th century who wrote a biography of Aesop based on The Aesop Romance and conjectured that Aesop might have been Ethiopian, given his name.[31] An English translation of Planudes' biography from 1687 says that "his Complexion [was] black, from which dark Tincture he contracted his Name (Aesopus being the same with Aethiops)". When asked his origin by a prospective new master, Aesop replies, "I am a Negro"; numerous illustrations by Francis Barlow accompany this text and depict Aesop accordingly.[32] But according to Gert-Jan van Dijk, "Planudes' derivation of 'Aesop' from 'Aethiopian' is...etymologically incorrect,"[33] and Frank Snowden says that Planudes' account is "worthless as to the reliability of Aesop as 'Ethiopian.'"[34]

The tradition of Aesop's African origin was carried forward into the 19th century. The frontispiece of William Godwin's Fables Ancient and Modern (1805) has a copperplate illustration of Aesop relating his stories to little children that gives his features a distinctly negroid appearance.[35] The collection includes the fable of "Washing the Blackamoor white", although updating it and making the Ethiopian 'a black footman'. In 1856 William Martin Leake repeated the false etymological linkage of "Aesop" with "Aethiop" when he suggested that the "head of a negro" found on several coins from ancient Delphi (with specimens dated as early as 520 BCE)[36] might depict Aesop, presumably to commemorate (and atone for) his execution at Delphi,[37] but Theodor Panofka supposed the head to be a portrait of Delphos, founder of Delphi,[38] a view more widely repeated by later historians.[39]

The idea that Aesop was Ethiopian has been further encouraged by the presence of camels, elephants, and apes in the fables, even though these African elements are more likely to have come from Egypt and Libya than from Ethiopia, and the fables featuring African animals may have entered the body of Aesopic fables long after Aesop actually lived.[40] Nevertheless, in 1932 the anthropologist J.H. Driberg, repeating the Aesop/Aethiop linkage, asserted that, while "some say he [Aesop] was a Phrygian...the more general view...is that he was an African", and "if Aesop was not an African, he ought to have been;"[41] and in 2002 Richard A. Lobban cited the number of African animals and "artifacts" in the Aesopic fables as "circumstantial evidence" that Aesop may have been a Nubian folkteller.[42]

Popular perception of Aesop as black may have been further encouraged by a perceived similarity between fables of the trickster Br'er Rabbit, told by African-American slaves, and the traditional role of the slave Aesop as 'a kind of culture hero of the oppressed, and the Life [of Aesop] as a how-to handbook for the successful manipulation of superiors.'[43] This is reinforced by the 1971 TV production Aesop's Fables in which Bill Cosby played Aesop. In this mixture of live action and animation, two black children wander into an enchanted grove, where Aesop tells them fables that differentiate between realistic and unrealistic ambition. His version there of the Tortoise and the Hare illustrates how to take advantage of an opponent's over-confidence.[44]

On other continents Aesop has occasionally undergone a degree of acculturation. This is evident in Isango Portobello's 2010 production of the play Aesop's Fables at the Fugard Theatre in Cape Town, South Africa. Based on a script by British playwright Peter Terson (1983),[45] it was radically adapted by the director Mark Dornford-May as a musical using native African instrumentation, dance and stage conventions.[46] Although Aesop is portrayed as Greek, and dressed in the short Greek tunic, the all-black production contextualises the story in the recent history of South Africa. The former slave, we are told 'learns that liberty comes with responsibility as he journeys to his own freedom, joined by the animal characters of his parable-like fables'.[47] One might compare with this Brian Seward's Aesop's Fabulous Fables (2009), which first played in Singapore with a cast of mixed ethnicities. In it Chinese theatrical routines are merged with those of a standard musical.[48]

There had already been an example of Asian acculturation in 17th century Japan. There Portugese missionaries had introduced a translation of the fables (Esopo no Fabulas, 1593) that included the biography of Aesop. This was then taken up by Japanese printers and taken through several editions under the title Isopo Monogatari. Even when Europeans were expelled from Japan and Christianity proscribed, this text survived, in part because the figure of Aesop had been assimilated into the culture and depicted in woodcuts as dressed in Japanese costume.[49]

Depictions of Aesop in art and literature

Appearances of Aesop in art and popular culture began in ancient Greece and continue to the present. Early on, the perennial representation of Aesop as an ugly slave emerged. Another recurrent motif is the love story of the slaves Aesop and Rhodopis. The tradition which makes Aesop a black African has resulted in several such depictions, ranging from 17th century engravings to television portrayal by a black comedian. Some feature combinations of these motifs, or eschew them altogether (as in the portrayal of Aesop in The Bullwinkle Show.[50] In general, beginning in the 20th century, plays have shown Aesop as a slave, but not ugly, while Hollywood movies and television shows have depicted him as neither ugly nor a slave.

In 1843, the archaeologist Otto Jahn suggested that Aesop was the person depicted on a Greek red-figure cup, c.450 BCE, in the Vatican Museums.[51] Paul Zanker describes the figure as a man with "emaciated body and oversized head...furrowed brow and open mouth", who "listens carefully to the teachings of the fox sitting before him. He has pulled his mantle tightly around his meagre body, as if he were shivering...he is ugly, with long hair, bald head, and unkempt, scraggly beard, and is clearly uncaring of his appearance."[52]

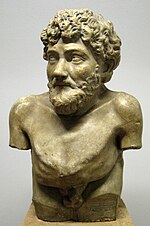

Some archaeologists have suggested that a Hellenistic statue of a bearded man with a deformed torso in the Villa Albani in Rome depicts Aesop (see photo elsewhere on this page); but as François Lissarrague points out, "It could be the realistic portrait of some individual unknown to us, or an expressive portrait like others known to exist in Hellenistic art. The sole argument advanced to identify the fabulist in this work is the facial expression: He looks intelligent. Admittedly, this evidence is a bit meager."[53]

Aesop also began to appear early in literary works. The 4th century BCE Athenian playwright Alexis put Aesop on the stage in his comedy "Aesop", of which a few lines survive (Athenaeus 10.432); conversing with Solon, Aesop praises the Athenian practice of adding water to wine.[54] Leslie Kurke suggests that Aesop may be been "a staple of the comic stage" of this era.[55]

The 3rd century BCE poet Poseidippus of Pella wrote a narrative poem entitled "Aesopia" (now lost), in which Aesop's fellow slave Rhodopis (under her original name Doricha) was frequently mentioned, according to Athenaeus 13.596. Pliny would later identify Rhodopis as Aesop's lover,[56] a romantic motif that would be repeated in subsequent popular depictions of Aesop.

The fabulist then makes a cameo appearance in the novel A True Story by the 2nd-century satirist Lucian; when the narrator arrives at the Island of the Blessed, he finds that "Aesop the Phrygian was there, too; he acts as their jester."[57]

Beginning with the Heinrich Steinhowel edition of 1476, many translations of the fables into European languages, which also incorporated Planudes' Life of Aesop, featured illustrations depicting him as a hunchback. The 1687 edition of Aesop's Fables with His Life: in English, French and Latin included 28 engravings by Francis Barlow which show him as a dwarfish hunchback, and his facial features appear to accord with his statement in the text (p. 7), "I am a Negro" (see illustration on this page).

The Spaniard Diego Velázquez painted a portrait of Aesop, dated 1639-40 and now in the collection of the Museo del Prado. The presentation is anachronistic and Aesop, while arguably not handsome, displays no physical deformities. It was partnered by another portrait of Menippus, a satirical philosopher equally of slave-origin. A similar philosophers series was painted by fellow Spaniard Jusepe de Ribera,[58] who is credited with two portraits of Aesop. "Aesop, poet of the fables" is in the El Escorial gallery and pictures him as an author leaning on a staff by a table which holds copies of his work, one of them a book with the name Hissopo on the cover.[59] The other is in the Museo de Prado, dated 1640-50 and titled "Aesop in beggar’s rags". There he is also shown at a table, holding a sheet of paper in his left hand and writing with the other.[60] While the former hints at his lameness and deformed back, the latter only emphasises his poverty.

In 1690, French playwright Edmé Boursault's Les fables d'Esope (later known as Esope à la ville) premiered in Paris. A sequel, Esope à la cour (Aesop at Court), was first performed in 1701; drawing on a mention in Herodotus 2.134-5 that Aesop had once been owned by the same master as Rhodopis, and the statement in Pliny 36.17 that she was Aesop's concubine as well, the play introduced Rodope as Aesop's mistress, a romantic motif that would be repeated in later popular depictions of Aesop.

Sir John Vanbrugh's comedy "Aesop" premiered at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, London, in 1697 and was frequently performed there for the next twenty years. A translation and adaptation of Boursault's Les fables d'Esope, Vanbrugh's play depicted a physically ugly Aesop acting as adviser to Learchus, governor of Cyzicus under King Croesus, and using his fables to solve romantic problems and quiet political unrest.[61]

In 1780, the anonymously authored novelette The History and Amours of Rhodope was published in London. The story casts the two slaves Rhodope and Aesop as unlikely lovers, one ugly and the other beautiful; ultimately Rhodope is parted from Aesop and marries the Pharaoh of Egypt. Some editions of the volume were illustrated with an engraving by Francesco Bartolozzi of a work by painter Angelica Kauffmann depicting Aesop and Rhodope.

In 1844, Walter Savage Landor, famed for his series of Imaginary Conversations, published a fictional dialogue between Aesop and Rhodope in the volume The Book of Beauty; Aesop describes himself as "undersized and distorted."

Depictions in popular culture

Abandoning the perennial image of Aesop as an ugly slave, the movie Night in Paradise (1946) cast Turhan Bey in the role, depicting Aesop as an advisor to King Croesus who falls in love with the king's intended bride, a Persian princess played by Merle Oberon. There was also the 1953 teleplay "Aesop and Rhodope" by Helene Hanff, broadcast on Hallmark Hall of Fame with Lamont Johnson playing Aesop.

"A raposa e as uvas" ("The Fox and the Grapes"), a play in three acts about the life of Aesop by Brazilian dramatist Guilherme Figueiredo, was published in 1953 and has been performed in many countries, including a videotaped production in China in 2000 under the title Hu li yu pu tao or 狐狸与葡萄.

Beginning in 1959, animated shorts under the title "Aesop and Son" appeared as a recurring segment in the TV series Rocky and His Friends[62] and its successor, The Bullwinkle Show.[50] The image of Aesop as ugly slave was abandoned; Aesop (voiced by Charles Ruggles), a Greek citizen, would recount a fable for the edification of his son, Aesop Jr., who would then deliver the moral in the form of an atrocious pun. Aesop's 1998 appearance in the episode "Hercules and the Kids" in the animated TV series Hercules (voiced by Robert Keeshan) amounted to little more than a cameo.

Occasions on which Aesop is portrayed as black include Richard Durham's "Destination Freedom" radio show broadcast (1949), where the drama "The Death of Aesop," portrays him as an Ethiopian. In 1971, Bill Cosby played Aesop in the TV production Aesop's Fables.

The musical Aesop's Fables by British playwright Peter Terson was first produced in 1983.[45] In 2010, the play was staged at the Fugard Theatre in Cape Town, South Africa with Mhlekahi Mosiea in the role of Aesop (see above).

Notes

- ^ West, pp. 106 and 119.

- ^ Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopaedia of the Ancient World (hereafter BNP) 1:256.

- ^ Callimachus, Iambus 2 (Loeb fragment 192)

- ^ Maximus of Tyre, Oration 36.1

- ^ Aristotle, Rhetoric 2.20.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 2.134.

- ^ Plutarch, On the Delays of Divine Vengeance; Banquet of the Seven Sages; Life of Solon.

- ^ Kurke 2010, p. 135.

- ^ Ben Edwin Perry, Introduction to Babrius and Phaedrus, pp. xxxviii-xlv.

- ^ BNP 1:256.

- ^ Phaedrus 1.2

- ^ William Hansen, review of Vita Aesopi: Ueberlieferung, Sprach und Edition einer fruehbyzantinischen Fassung des Aesopromans by Grammatiki A. Karla in Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2004.09.39.

- ^ Leslie Kurke, "Aesop and the Contestation of Delphic Authority", in The Cultures Within Ancient Greek Culture: Contact, Conflict, Collaboration, ed. Carol Dougherty and Leslie Kurke, p. 77.

- ^ François Lissarrague, "Aesop, Between Man and Beast: Ancient Portraits and Illustrations", in Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art, ed. Beth Cohen (hereafter, Lissarrague), p. 133.

- ^ Lissarrague, p. 113.

- ^ BNP 1:257; West, p. 121; Hägg, p. 47.

- ^ Hägg, p. 47; also West, p. 122.

- ^ Athenaeus 13.82.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo 61b.

- ^ Diogenes Laertius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers 2.5.42: "He also composed a fable, in the style of Aesop, not very artistically, and it begins—Aesop one day did this sage counsel give / To the Corinthian magistrates: not to trust / The cause of virtue to the people's judgment."

- ^ Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights 2.29.

- ^ Ben E. Perry, Demetrius of Phalerum and the Aesopic Fables, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 93, 1962, pp.287-346

- ^ Ausonius, Epistles 12.

- ^ BNP 1:258-9; West; Niklas Holzberg, The Ancient Fable: An Introduction, pp. 12-13; see also Ainoi, Logoi, Mythoi: Fables in Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic Greek by Gert-Jan van Dijk and History of the Graeco-Latin Fable by Francisco Rodriguez Adrado.

- ^ The Aesop Romance, translated by Lloyd W. Daly, in Anthology of Ancient Greek Popular Literature, ed. William Hansen, p. 111.

- ^ Papademetriou, pp. 14-15.

- ^ Himerius, Orations 46.4, translated by Robert J. Penella in Man and the Word: The Orations of Himerius, p. 250.

- ^ See Lissarrage; Papademetriou; Compton, Victim of the Muses; Lefkowitz, "Ugliness and Value in the Life of Aesop" in Kakos: Badness and Anti-value in Classical Antiquity ed. Sluiter and Rosen.

- ^ BNP 1:257.

- ^ Lobban, 2004, pp. 8-9.

- ^ "...niger, unde & nomen adeptus est (idem enim Aesopus quod Aethiops)" is one Latin translation of Planudes' Greek; see Aesopi Phrygis Fabulae, p. 9.

- ^ Tho. Philipott (translating Planudes), Aesop's Fables with His Life: in English, French and Latin, pp. 1 and 7.

- ^ Gert-Jan van Dijk, "Aesop" entry in The Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece, ed. Nigel Wilson, p. 18.

- ^ Frank M. Snowden, Jr., Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience (hereafter Snowden), p. 264.

- ^ Godwin then used the nom de plume of Edward Baldwin. The cover can be viewed online

- ^ Ancient Coins of Phocis web page, accessed 11-12-2010.

- ^ William Martin Leake, Numismata Hellenica: A Catalogue of Greek Coins, p. 45.

- ^ Theodor Panofka, Antikenkranz zum fünften Berliner Winckelmannsfest: Delphi und Melaine, p. 7; an illustration of the coin in question follows p. 16.

- ^ Snowden, pp. 150-51 and 307-8.

- ^ Robert Temple, Introduction to Aesop: The Complete Fables, pp. xx-xxi.

- ^ Driberg, 1932.

- ^ Lobban, 2002.

- ^ Kurke 2010, pp. 11-12.

- ^ Available in two sections on YouTube

- ^ a b Playwrights and Their Stage Works: Peter Terson

- ^ "Backstage with 'Aesop's Fables' Director Mark Dornford-May", Sunday Times (Cape Town), June 7, 2010.

- ^ "Aesop's Fables at the Fugard" (online listing); there are also short publicity excerpts on YouTube here and here

- ^ There are short excerpts on YouTube

- ^ Two academic studies support this conclusion: J.S.A. Elisonas: Fables and Imitations: Kirishitan literature in the forest of simple letters, Bulletin of Portugese Japanese Studies, Lisbon 2002, pp.13-17 (for consideration of Isoho Monogatari) and Lawrence Marceau, From Aesop to Esopo to Isopo: Adapting the Fables in Late Medieval Japan (2009); an abstract of this paper appears on p.277

- ^ a b The Bullwinkle Show at IMDb

- ^ Lissarrague, p.137.

- ^ Paul Zanker, The Mask of Socrates, pp. 33-34.

- ^ Lissarrague, p. 139.

- ^ Attribution of these lines to Aesop is conjectural; see the reference and footnote in Kurke 2010, p 356.

- ^ Kurke 2010, p. 356.

- ^ Pliny 36.17

- ^ Lucian, Verae Historiae (A True Story) 2.18 (Reardon translation).

- ^ There is a note on another from this series on the Christies site

- ^ http://www.lessing-photo.com/p3/391913/39191333.jpg

- ^ http://www.fineart-china.com/upload1/file-admin/images/new7/Diego%20Velazquez-288688.jpg

- ^ Mark Loveridge, A History of Augustan Fable (hereafter Loveridge), pp. 166-68.

- ^ Rocky and His Friends at IMDb

References

- Adrado, Francisco Rodriguez, 1999-2003. History of the Graeco-Latin Fable (three volumes). Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers.

- Cancik, Hubert, et al., 2002. Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopaedia of the Ancient World. Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers.

- Cohen, Beth (editor), 2000. Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art. Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers. Includes "Aesop, Between Man and Beast: Ancient Portraits and Illustrations" by François Lissarrague.

- Dougherty, Carol and Leslie Kurke (editors), 2003. The Cultures Within Ancient Greek Culture: Contact, Conflict, Collaboration. Cambridge University Press. Includes "Aesop and the Contestation of Delphic Authority" by Leslie Kurke.

- Driberg, J.H., 1932. "Aesop", The Spectator, vol. 148 #5425, June 18, 1932, pp. 857–8.

- Hansen, William (editor), 1998. Anthology of Ancient Greek Popular Literature. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Includes The Aesop Romance (The Book of Xanthus the Philosopher and Aesop His Slave or The Career of Aesop), translated by Lloyd W. Daly.

- Hägg, Tomas, 2004. Parthenope: Selected Studies in Ancient Greek Fiction (1969-2004). Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. Includes Hägg's "A Professor and his Slave: Conventions and Values in The Life of Aesop", first published in 1997.

- Hansen, William, 2004. Review of Vita Aesopi: Ueberlieferung, Sprach und Edition einer fruehbyzantinischen Fassung des Aesopromans by Grammatiki A. Karla. Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2004.09.39.

- Holzberg, Niklas, 2002. The Ancient Fable: An Introduction, translated by Christine Jackson-Holzberg. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University press.

- Keller, John E., and Keating, L. Clark, 1993. Aesop's Fables, with a Life of Aesop. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press. English translation of the first Spanish edition of Aesop from 1489, La vida del Ysopet con sus fabulas historiadas including original woodcut illsutrations; the Life of Aesop is a version from Planudes.

- Kurke, Leslie, 2010. Aesopic Conversations: Popular Tradition, Cultural Dialogue, and the Invention of Greek Prose. Princeton University Press.

- Leake, William Martin, 1856. Numismata Hellenica: A Catalogue of Greek Coins. London: John Murray.

- Loveridge, Mark, 1998. A History of Augustan Fable. Cambridge university Press.

- Lobban, Richard A., Jr., 2002. "Was Aesop a Nubian Kummaji (Folkteller)?", Northeast African Studies, 9:1 (2002), pp. 11–31.

- Lobban, Richard A., Jr., 2004. Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press.

- Panofka, Theodor, 1849. Antikenkranz zum fünften Berliner Winckelmannsfest: Delphi und Melaine. Berlin: J. Guttentag.

- Papademetriou, J. Th., 1997. Aesop as an Archetypal Hero. Studies and Research 39. Athens: Hellenic Society for Humanistic Studies.

- Penella, Robert J., 2007. Man and the Word: The Orations of Himerius." Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Perry, Ben Edwin (translator), 1965. Babrius and Phaedrus. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Philipott, Tho. (translator), 1687. Aesop's Fables with His Life: in English, French and Latin. London: printed for H. Hills jun. for Francis Barlow. Includes Philipott's English translation of Planudes' Life of Aesop with illustrations by Francis Barlow.

- Reardon, B.P. (editor), 1989. Collected Ancient Greek Novels. Berkeley: University of California Press. Includes An Ethiopian Story by Heliodorus, translated by J.R. Morgan, and A True Story by Lucian, translated by B.P. Reardon.

- Snowden, Jr., Frank M., 1970. Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Temple, Robert and Olivia (translators), 1998. Aesop: The Complete Fables. New York: Penguin Books.

- van Dijk, Gert-Jan, 1997. Ainoi, Logoi, Mythoi: Fables in Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic Greek. Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers.

- West, M.L., 1984. "The Ascription of Fables to Aesop in Archaic and Classical Greece", La Fable (Vandœuvres–Genève: Fondation Hardt, Entretiens XXX), pp. 105–36.

- Wilson, Nigel, 2006. Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. New York: Routledge.

- Zanker, Paul, 1995. The Mask of Socrates: The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Further reading

- Anonymous, 1780. The History and Amours of Rhodope. London: Printed for E.M Diemer.

- Anthony, Mayvis, 2006. The Legendary Life and Fables of Aesop. Toronto: Mayant Press. A retelling of the Life of Aesop for children.

- Caoursin, William, The Siege of Rhodes, London (1482), with Aesopus, The Book of Subtyl Histories and Fables of Esope (1484). Facsimile ed., 2 vols. in 1, Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, 1975. ISBN 978-0-8201-1154-4.

- Caxton, William, 1484. The history and fables of Aesop, Westminster. Modern reprint edited by Robert T. Lenaghan (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1967). Includes Caxton's Epilogue to the Fables, dated March 26, 1484.

- Clayton, Edward. "Aesop, Aristotle, and Animals: The Role of Fables in Human Life". Humanitas, Volume XXI, Nos. 1 and 2, 2008, pp. 179–200. Bowie, Maryland: National Humanities Institute.

- Compton, Todd, 1990. "The Trial of the Satirist: Poetic Vitae (Aesop, Archilochus, Homer) as Background for Plato's Apology", The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 111, No. 3 (Autumn, 1990), pp. 330–347. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Compton, Todd, 2006. Victim of the Muses: Poet as Scapegoat, Warrior and Hero in Greco-Roman And Indo-European Myth and History. Washington, D.C.: Center for Hellenic Studies.

- Daly, Lloyd W., 1961. Aesop Without Morals: The Famous Fables, and a Life of Aesop, Newly Translated and Edited. New York and London: Thomas Yoseloff. Includes Daly's translation of The Aesop Romance.

- Figueiredo, Guilherme, 1953? The Fox and the Grapes (English translation of A raposa e as uvas). New York: Brazilian-American Cultural Institute.

- Gibbs, Laura (translator), 2002, reissued 2008. Aesop's Fables. Oxford University Press.

- Gibbs, Laura. "Aesop Illustrations: Telling the Story in Images", Journey to the Sea (online journal), issue 6, December 1, 2008.

- Gibbs, Laura. "Life of Aesop: The Wise Fool and the Philosopher", Journey to the Sea (online journal), issue 9, March 1, 2009.

- Jacobs, Joseph, The fables of Aesop: as first printed by William Caxton in 1484, London : David Nutt, 1889.

- Perry, Ben Edwin (editor), 1952, 2nd edition 2007. Aesopica: A Series of Texts Relating to Aesop or Ascribed to Him. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Sluiter, Ineke and Rosen, Ralph M. (editors), 2008. Kakos: Badness and Anti-value in Classical Antiquity. Mnemosyne: Supplements. History and Archaeology of Classical Antiquity; 307. Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers. Includes "Ugliness and Value in the Life of Aesop" by Jeremy B. Lefkowitz.

- Temple, Robert, "Fables, Riddles, and Mysteries of Delphi", Proceedings of 4th Philosophical Meeting on Contemporary Problems, No 4, 1999 (Athens, Greece) In Greek and English.

- Wills, Lawrence M., 1997. The Quest of the Historical Gospel: Mark, John, and the Origins of the Gospel Genre. London and New York: Routledge. Includes, an appendix, Wills' English translation of the Life of Aesop, pp. 180–215.

External links

- Aesop's Fables Free audio downloads

- Aesop's Fables Intended for children

- Aesop's Fables by V. S. Vernon Jones

- Aesop's Fables with illustrations by Harrison Weir, John Tenniel, Ernest Griset, and others

- AesopFables.com Large collection of fables; many are not Aesopic

- Aesopica.net Over 600 fables in English, with Latin and Greek texts also; searchable

- Carlson Fable Collection at Creighton University Includes online catalog of fable-related objects

- Vita Aesopi Online resources for the Life of Aesop

- Works by Aesop at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Aesop at Open Library

f