Orion (Constellation program): Difference between revisions

near earth object, not near earth orbit |

→Design: correction: the payload bay doors are a critical part of the shuttle orbiter; they are its heat rejection radiatiors, and serious damage to them would force a mission abort and prompt deorbit |

||

| Line 138: | Line 138: | ||

[[File:Orion Ground Test Article (GTA).jpg|thumb|left|Orion Ground Test Article in Denver, Colorado]] |

[[File:Orion Ground Test Article (GTA).jpg|thumb|left|Orion Ground Test Article in Denver, Colorado]] |

||

Another feature will be the partial reusability of the Orion CM. NASA aims to reuse each craft for up to ten flights, allowing it to build a fleet of both manned and unmanned Orion CMs. Both the CM and SM will be constructed of the [[Al-Li|aluminium lithium]] (Al/Li) alloy currently used on the shuttle's [[Space Shuttle external tank|external tank]], and the [[Delta IV rocket|Delta IV]] and [[Atlas V]] rockets. The CM itself will be covered in the same [[Nomex]] felt-like thermal protection blankets used on |

Another feature will be the partial reusability of the Orion CM. NASA aims to reuse each craft for up to ten flights, allowing it to build a fleet of both manned and unmanned Orion CMs. Both the CM and SM will be constructed of the [[Al-Li|aluminium lithium]] (Al/Li) alloy currently used on the shuttle's [[Space Shuttle external tank|external tank]], and the [[Delta IV rocket|Delta IV]] and [[Atlas V]] rockets. The CM itself will be covered in the same [[Nomex]] felt-like thermal protection blankets used on parts on the shuttle not subject to critical heating, such as the payload bay doors. The reusable recovery parachutes will be based on the parachutes used on both the Apollo spacecraft and the [[Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster]]s, and will also use the same Nomex cloth for construction. Water landings will be the exclusive means of recovery for the Orion CM.<ref name="nasaspaceflight2007">{{cite web | title = Orion landings to be splashdowns - KSC buildings to be demolished | publisher = NASA SpaceFlight.com | date = 2007-08-05 | url = http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2007/08/orion-landings-to-be-splashdowns-ksc-buildings-to-be-demolished/ | accessdate = 2007-08-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title = NASA Denies Making Orion Water Landing Decision - and Deleting Touchdowns on Land | publisher = NASA Watch | date = 2007-08-06 | url = http://nasawatch.com/archives/2007/08/nasa-denies-making-orion-water-landing-decision---and-deleting-touchdowns-on-land.html | accessdate = 2010-11-23}}</ref> |

||

To allow the Orion spacecraft to service the International Space Station, and to mate with other Constellation vehicles, it will use a new [[Low Impact Docking System]], a simplified version of the [[Androgynous Peripheral Attach System|universal docking ring]] currently used on the shuttle fleet, which itself was a Soviet design that originated during the 1975 [[Apollo-Soyuz Test Project]]. Both the spacecraft and docking adapter will employ a [[Launch escape system|Launch Escape System]] (LES) like that used in Mercury and Apollo, along with an Apollo-derived "Boost Protective Cover" (made of [[fiberglass]]), to protect the Orion CM from aerodynamic and impact stresses during the first 2½ minutes of ascent. |

To allow the Orion spacecraft to service the International Space Station, and to mate with other Constellation vehicles, it will use a new [[Low Impact Docking System]], a simplified version of the [[Androgynous Peripheral Attach System|universal docking ring]] currently used on the shuttle fleet, which itself was a Soviet design that originated during the 1975 [[Apollo-Soyuz Test Project]]. Both the spacecraft and docking adapter will employ a [[Launch escape system|Launch Escape System]] (LES) like that used in Mercury and Apollo, along with an Apollo-derived "Boost Protective Cover" (made of [[fiberglass]]), to protect the Orion CM from aerodynamic and impact stresses during the first 2½ minutes of ascent. |

||

Revision as of 22:48, 15 July 2011

This article needs to be updated. (December 2010) |

| |

|---|---|

| Description | |

| Role: | Beyond low Earth orbit, back-up for commercial cargo and crew to the ISS[1] |

| Crew: | 2-4[2] |

| Carrier Rocket: | Space Launch System[3] (planned) |

| Launch Date: | 2016[1] |

| Dimensions | |

| Height: | |

| Diameter: | 5 m (16.5 ft) |

| Pressurized Volume: | 19.56 m3 (691 cu ft) [2] |

| Habitable Volume: | 8.95 m3 (316 cu ft) [2] |

| Capsule Mass: | 8,913 kg (19,650 lb) |

| Service Module Mass: | 12,337 kg (27,198 lb) |

| Total Mass: | 21,250 kg (46,848 lb) |

| Service Module Propellant Mass: | 7,907 kg (17,433 lb) |

| Performance | |

| Total delta-v: | 1,595 m/s |

| Endurance: | 21.1 days[2] |

| |

Orion is a spacecraft designed by Lockheed Martin for NASA, the space agency of the United States. Orion development began in 2005 as part of the Constellation program, where Orion would fulfill the function of a Crew Exploration Vehicle. Each Orion spacecraft was projected to carry a crew of four astronauts. The spacecraft was originally designed to be launched by the Ares I launch vehicle. As of 11 October 2010, with the canceling of the Constellation Program, the Ares program ended and the Orion vehicle is planned to be launched on top of an intended cheaper alternative Space Launch System, to the Ares series.

The first orbital test flight of the Orion was planned for 2013, abort tests in 2014[4] and the first crewed Orion flight was anticipated in 2016.[1] If commercial orbital transportation services are unavailable, Orion would handle logistic flights to the International Space Station.[5]

The federal government proposed cancellation of the Constellation program in February 2010 and was signed into law October 11.[6] The bill is basically a retooling of the Constellation Program, moving the objective away from a moon base and more towards a Near-Earth object (NEO) mission and an eventual Mars landing.

History

On January 14, 2004, President George W. Bush announced the Orion spacecraft, known then as the Crew Exploration Vehicle (CEV), as part of the Vision for Space Exploration:

Our second goal is to develop and test a new spacecraft, the Crew Exploration Vehicle, by 2008, and to conduct the first manned mission no later than 2014. The Crew Exploration Vehicle will be capable of ferrying astronauts and scientists to the Space Station after the shuttle is retired. But the main purpose of this spacecraft will be to carry astronauts beyond our orbit to other worlds. This will be the first spacecraft of its kind since the Apollo Command Module.[7]

The proposal to create the Orion spacecraft was partly a reaction to the Space Shuttle Columbia accident, the subsequent findings and report by the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB), and the White House's review of the American space program. The Orion spacecraft effectively replaced the conceptual Orbital Space Plane (OSP), which itself was proposed after the failure of the Lockheed Martin X-33 program to produce a replacement for the space shuttle.

The name is derived from the constellation of Orion, and was also used on the Apollo 16 Lunar Module that carried astronauts John W. Young and Charlie Duke to the lunar surface in April 1972.

After the replacement of Sean O'Keefe, NASA's procurement schedule and strategy completely changed, as described above. In July 2004, before he was named NASA administrator, Michael Griffin participated in a study called "Extending Human Presence Into the Solar System"[8] for The Planetary Society, as a co-team leader. The study offers a strategy for carrying out Project Constellation in an affordable and achievable manner. Since Griffin was one of the leaders of the study, it can be assumed that he agrees with its conclusions, and the study may show insight into possible future developments of the CEV. Griffin's actions as administrator supported the goals of the plan.

According to the executive summary, the study was built around "a staged approach to human exploration beyond low Earth orbit (LEO)."[8] It recommends that Project Constellation be carried out in three distinct stages. These are:

- Stage 1 – "Features the development of a new crew exploration vehicle (CEV), the completion of the International Space Station (ISS), and an early retirement of the shuttle orbiter. Orbiter retirement would be made as soon as the ISS U.S. Core is completed (perhaps only 6 or 7 flights) and the smallest number of additional flights necessary to satisfy our international partners’ ISS requirements. Money saved by early orbiter retirement would be used to accelerate the CEV development schedule to minimize or eliminate any hiatus in U.S. capability to reach and return from LEO."[8]

- Stage 2 – "Requires the development of additional assets, including an uprated CEV capable of extended missions of many months in interplanetary space. Habitation, laboratory, consumables, and propulsion modules, to enable human flight to the vicinities of the Moon and Mars, the Lagrange points, and certain near-Earth asteroids."[8]

- Stage 3 – "Development of human-rated planetary landers is completed in Stage 3, allowing human missions to the surface of the Moon and Mars beginning around 2020."[8]

A number of changes to the original CEV acquisition strategy were explained in a NASA study called the Exploration Systems Architecture Study. The results were presented at a news conference held on September 19, 2005.[9] The ESAS recommends strategies for flying the manned Orion by 2014, and endorses a Lunar Orbit Rendezvous approach to the Moon. The LEO versions of Orion was intended carry crews of four to six to the ISS. The lunar version of the Orion would carry a crew of four and the Mars Orion would carry six[citation needed]. Cargo would also be carried aboard an unmanned version of Orion, similar to the Russian Progress cargo ships. The contractor for the Orion is Lockheed Martin, which was selected by NASA in September, 2006 and is the current contractor for the Space Shuttle's External Tank and the Atlas V EELV.

The Orion spacecraft (CEV) will be an Apollo-like capsule, not a lifting body or winged vehicle like the current Shuttle. Like the Apollo Command Module, Orion would be attached to a service module for life support and propulsion. It is intended to land in water but past versions had included plans for it to land on land. Landing on the west coast would allow the majority of the reentry path to be flown over the Pacific Ocean rather than populated areas. Orion will have an AVCOAT ablative[10] heat shield that would be discarded after each use.

The Orion spacecraft (CEV) would weigh about 25 tons (23 tonnes) ... almost four times the mass of the Apollo Command Module at 6.4 tons (5.8 tonnes) ... and, with a diameter of 16.5 feet (5 metres) vice 12.8 feet (3.9 metres) provide 2.5 times greater volume.[11]

Accelerated lunar mission development is slated to start by 2010, once the Shuttle is retired. The Lunar Surface Access Module (LSAM) and heavy-lift boosters would be developed in parallel and would both be ready for flight by 2018. The eventual goal is to achieve a lunar landing by 2020. The LSAM would be much larger than the Apollo Lunar Module and is anticipated to be capable of carrying up to around 23 tons (21 tonnes) of cargo to the lunar surface to support a lunar outpost (t.b.d.). This weight in cargo is greater than the mass of the entire Apollo Lunar Module.

Like the Apollo Lunar Module, the LSAM would include a descent stage for landing and an ascent stage for returning to orbit. The crew of four would ride in the ascent stage. The ascent stage would be powered by a methane/oxygen fuel for return to lunar orbit (later changed to liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, due to the infancy of oxygen/methane rocket propulsion). This would allow a derivative of the same lander to be used on later Mars missions, where methane propellant can be manufactured from the Martian soil in a process known as in-situ resource utilization (ISRU). The LSAM would support the crew of four on the lunar surface for about a week and use advanced roving vehicles to explore the lunar surface. The huge amount of cargo carried by the LSAM would be extremely beneficial for supporting a lunar base and for bringing large amounts of scientific equipment to the lunar surface.

Design revisions and updates

- July 2006 design revisions

In late July 2006 NASA's second design review resulted in major changes to the spacecraft design.[12] Originally, NASA wanted to use liquid methane (LCH4) as the SM fuel, but due to the infancy of oxygen/methane-powered rocket technologies and the need to launch the Orion by 2012, the switch to hypergolic propellants was mandated in late July 2006. This switch will allow NASA to man-rate the Orion and Ares I stack by no later than 2011,[citation needed] and eliminate one potential cause of the gap between the shuttle's retirement in 2010 and the first manned Orion flight.[13]

- April 2007 contract revision

On April 20, 2007 NASA and Boeing signed a modification to the Orion contract. The updated contract adds two years to the Orion project design phase, adds two test flights of Orion's launch abort system, and deletes from the initial design phase production of a pressurized cargo carrier for the International Space Station.[14]

- May 2007 design update

An article in "Aerospace Daily & Defense Report" indicates that in the latest Orion design revision, called configuration "606" by Lockheed Martin, the service module will have exterior panels that are jettisoned shortly after the second stage engine of the Ares I ignites. This configuration will save 1,000 pounds of the mass compared with the prior "605" configuration.[15]

- August 2007 design update

On August 5, a report surfaced stating that the airbag landing system was removed from the next Orion design cycle ("607") in a weight saving measure, opting to return to an Apollo-style splashdown for the vehicle's end of mission.[16]

2009 Human Space Flight Plans Committee

On September 8, 2009, the Human Space Flight Plans Committee was scheduled to release a report proposing a short list of different long term plans for the US Government's human space flight program. The review was commissioned by the Obama Administration to take into account several objectives. These include support for the International Space Station, development of missions beyond low Earth orbit (including the Moon) and use of commercial space industry. These objectives must fit within a defined budget profile.[17]

Among the parameters to be considered in the course of the review are "crew and mission safety, life-cycle costs, development time, national space industrial base impacts, potential to spur innovation and encourage competition, and the implications and impacts of transitioning from current human space flight systems". The review considered the appropriate amounts of research and development and "complementary robotic activity necessary to support various human space flight activities". It also "explores options for extending International Space Station operations beyond 2016".[18]

Funding and expected cost

President Bush's budget request for Fiscal Year 2005 included "$428 million for Project Constellation ($6.6 billion over five years) to develop a new crew exploration vehicle". The budget for FY2005 was confirmed by the Congress in November 2004 with full funding for the CEV.

The FY2006 budget request includes $753 million for continuing development of the CEV. As of 2005[update] the total development costs of the CEV are estimated at $15 billion.[19]

Lockheed Martin's contract for the initial "Schedule A" part of the Orion project, awarded on August 31, 2006 and running through 2013, is worth $3.9 billion. Additional development options in the "Schedule B" part of the contract could be worth up to another $3.5 billion.[20]

Although to date the exploration systems have received full funding and a House endorsement,[21] there was a possibility that rising shuttle Return To Flight costs would make funding of CEV development extremely difficult. There has been discussion of either obtaining a special supplemental from Congress to pay for the extra shuttle costs, or of involving private industry in CEV development and operations.[22] The total funding of Project Constellation through 2025, inflation-adjusted and without any other increases to NASA's budget, is estimated at $210 billion; the ESAS estimates the cost of the program through that date at being only $7 billion more, at $217 billion.[23] This cost may in fact end up lower as it includes developing new engines for the EDS instead of the newer idea of using J-2 derivatives.[23]

The White House's Augustine Commission estimated that after development of the Orion and its Ares I launch vehicle is completed, the system will have a recurring cost of nearly $1 billion per flight.[24]

Design

The Orion Crew and Service Module (CSM) stack consists of two main parts: a conical Crew Module (CM), and a cylindrical Service Module (SM) holding the spacecraft's propulsion system and expendable supplies. Both are based substantially on the Apollo Command and Service Modules (Apollo CSM) flown between 1967 and 1975, but include advances derived from the space shuttle program. "Going with known technology and known solutions lowers the risk," according to Neil Woodward, director of the integration office in the Exploration Systems Mission Directorate.[25]

Crew Module

The Orion CM will hold four to six crew members, compared to a maximum of three in the smaller Apollo CM or seven in the larger space shuttle. Despite its conceptual resemblance to the 1960s-era Apollo, Orion's CM will use several improved technologies, including:

- "Glass cockpit" digital control systems derived from that of the Boeing 787.[26]

- An "autodock" feature, like those of Russian Progress spacecraft and the European Automated Transfer Vehicle, with provision for the flight crew to take over in an emergency. Previous American spacecraft (Gemini, Apollo, and Space Shuttle) have all required manual piloting for docking.

- Improved waste-management facilities, with a miniature camping-style toilet and the unisex "relief tube" used on the space shuttle (whose system was based on that used on Skylab) and the International Space Station (based on the Soyuz, Salyut, and Mir systems). This eliminates the use of the much-hated plastic "Apollo bags" used by the Apollo crews.

- A nitrogen/oxygen (N2/O2) mixed atmosphere at either sea level (101.3 kPa (14.69 psi)*) or slightly reduced (55.2 to 70.3 kPa (8.01 to 10.20 psi)*) pressure.

- Much more advanced computers than on previous manned spacecraft.

Another feature will be the partial reusability of the Orion CM. NASA aims to reuse each craft for up to ten flights, allowing it to build a fleet of both manned and unmanned Orion CMs. Both the CM and SM will be constructed of the aluminium lithium (Al/Li) alloy currently used on the shuttle's external tank, and the Delta IV and Atlas V rockets. The CM itself will be covered in the same Nomex felt-like thermal protection blankets used on parts on the shuttle not subject to critical heating, such as the payload bay doors. The reusable recovery parachutes will be based on the parachutes used on both the Apollo spacecraft and the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Boosters, and will also use the same Nomex cloth for construction. Water landings will be the exclusive means of recovery for the Orion CM.[16][27]

To allow the Orion spacecraft to service the International Space Station, and to mate with other Constellation vehicles, it will use a new Low Impact Docking System, a simplified version of the universal docking ring currently used on the shuttle fleet, which itself was a Soviet design that originated during the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. Both the spacecraft and docking adapter will employ a Launch Escape System (LES) like that used in Mercury and Apollo, along with an Apollo-derived "Boost Protective Cover" (made of fiberglass), to protect the Orion CM from aerodynamic and impact stresses during the first 2½ minutes of ascent.

The Orion Crew Module (CM) is a 57.5° frustum shape, similar to that of the Apollo Command Module. As projected, the CM will be 5.02 meters (16 ft 6 in) in diameter and 3.3 meters (10 ft 10 in) in length,[28] with a mass of about 8.5 metric tons (19,000 lb). It is to be built by the Lockheed Martin Corporation.[29] It will have more than 2.5 times the volume of an Apollo capsule, which had an interior volume of 5.9 m3 (210 cu ft), and will carry four to six astronauts.[30] After extensive study, NASA has selected the Avcoat ablator system for the Orion crew module. Avcoat, which is composed of silica fibers with a resin in a honeycomb made of fiberglass and phenolic resin, was previously used on the Apollo missions and on select areas of the space shuttle for early flights.[31]

Service module

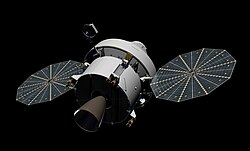

The service module designed for Orion will serve as the primary power and propulsion component of the spacecraft system, and like its predecessors, will be discarded at the end of each mission. Roughly cylindrical in shape, the Orion service module, like the crew module, will be constructed of Al-Li alloy (to keep weight down), and will feature a pair of deployable circular solar panels, similar in design to the panels used on the Mars Phoenix lander. The panels, the first to be used on a U.S. manned spacecraft (except for a 10-year period, the Soviet/Russian Soyuz spacecraft has used them since the first mission in 1967), will allow NASA to eliminate the need to carry malfunction-prone fuel cells, and its associated hardware (mainly LH2 tanks) from the service module, resulting in a shorter, yet more maneuverable spacecraft. Successful initial testing of an Orion solar array design using full-scale "UltraFlex wing" hardware was reported in October, 2008.[32]

The spacecraft's main propulsion system is an Aerojet AJ-10 rocket engine, derived from the second stage of the Delta II rocket, powered by hypergolic fuels, that are kept in helium pressured fuel cells. The SM Reaction Control System (RCS), the spacecraft's maneuvering thrusters (originally based on the Apollo "quad" system, but currently resembles that used on Gemini), will also be pressure-fed, and will use the same propellants. NASA believes the SM RCS would be able to act as a backup for a trans-Earth injection (TEI) burn in case the main SM engine fails.

A pair of LOX tanks (similar to those used in the Apollo SM) will provide, along with small tanks of nitrogen, the crew with breathing air at sea-level or "cruising altitude" pressure (10.2 to 14.7 psi), with a small "surge tank" providing necessary life support during reentry and touchdown. Lithium hydroxide (LiOH) cartridges will recycle the spacecraft's environmental system by "scrubbing" the carbon dioxide (CO2) exhaled by the astronauts from ship's air and adding fresh oxygen and nitrogen, which is then cycled back out into the system loop. Because of the switch from fuel cells to solar panels, the service module will have an onboard water tank which will provide drinking water for the crew, and (when mixed with glycol), cooling water for the spacecraft's electronics. Unlike the practice during Apollo of dumping both water and urine overboard during the flight, the Orion will have an onboard recycling system, identical to that used on the International Space Station, that will convert both waste water and urine into both drinking and cooling water.

The Service Module also mounts the spacecraft's waste heat management system (its radiators) and the aforementioned solar panels. These panels, along with backup batteries located in the Orion CM, will provide in-flight power to the ship's systems. The voltage, 28 volts DC, is similar to that used on the Apollo spacecraft during flight.

Like the Orion crew module, the Orion service module will be encapsulated by a fiberglass shroud that would be jettisoned at the same time as the LES/Boost Protective Cover, which would take place roughly 2½ minutes after launch (30 seconds after the solid rocket first stage is jettisoned). Prior to the "Orion 606" redesign, the Orion SM resembled a squat, enlarged version of the Apollo Service Module. The new "Orion 606" SM design retains the 5-meter width for the attachments of the Orion SM with the Orion CM, but utilizes a Soyuz-like service module design that allows Lockheed Martin to make the vehicle lighter in weight and permitting the attachment of the circular solar panels at the module's mid-points, like that of the Soyuz, instead of at the base near the spacecraft/rocket adapter, which may subject the panels to damage.

The Orion service module (SM) is projected comprising a cylindrical shape, having a diameter of 5.03 m (16 ft 6 in) and an overall length (including thruster) of 4.78 m (15 ft 8 in). With solar panels extended, span is either 17.00 m (55.77 ft) or 55.00 ft (16.76 m)[clarification needed]. The projected empty mass is 3,700 kg (8,000 lb), fuel capacity is 8,300 kg (18,000 lb).[33][34]

Launch Abort System

In the event of an emergency on the launch pad or during ascent, a launch escape system called the Launch Abort System (LAS) will separate the Crew Module from the launch vehicle using a solid rocket-powered launch abort motor (AM), which is more powerful than the Atlas 109-D booster that launched astronaut John Glenn into orbit in 1962.[35] There are two other propulsion systems in the LAS stack: the attitude control motor (ACM) and the jettison motor (JM). On July 10, 2007, Orbital Sciences, the prime contractor for the LAS, awarded Alliant Techsystems (ATK) a $62.5 million sub-contract to, "design, develop, produce, test and deliver the launch abort motor." ATK, which has the prime contract for the first stage of the Ares I rocket, intends to use an innovative "reverse flow" design for the motor.[36] On July 9, 2008 NASA announced that ATK has completed a vertical test stand at a facility in Promontory, Utah to test launch abort motors for the Orion spacecraft.[37] Another long-time space motor contractor, Aerojet, was awarded the jettison motor design and development contract for the LAS. As of September 2008 Aerojet has, along with team members Orbital Sciences, Lockheed Martin and NASA, successfully demonstrated two full-scale test firings of the jettison motor. This motor is important to every flight in that it functions to pull the LAS tower away from the vehicle after a successful launch. The motor also functions in the same manner for an abort scenario.

Another idea, recently floated by NASA, would see the LAS tower being replaced with the so-called Max Launch Abort System (MLAS), in which four existing solid-rocket motors, integrated into the boost protective cover and placed at 90° intervals, would fire and pull the Orion crew module away from an Ares I rocket in the event of a launchpad or in-flight abort during the first 2½ minutes of launch. If implemented in place of the LAS, the MLAS would allow NASA to reduce further weight of the Orion/Ares I stack (which has been described by critics as being overweight) and the design, which is shaped like a bullet, would reduce stresses on both the spacecraft and the launch vehicle, as well as reducing the overall height by 20–25 feet.

Abort tests

ATK successfully completed the first Orion launch-abort test on November 20, 2008. The abort motor will provide 500,000 lbf (2,200 kN) of thrust for an emergency on the launch pad or during the first 300,000 feet (91 km) of the rocket's climb to orbit. The test firing was the first time a motor with reverse flow propulsion technology at this scale has been tested.

This abort test firing brought together a series of motor and component tests conducted in 2008 as a preparation for the next major milestone, a full-size mock-up or boilerplate test scheduled for the spring of 2009.[38]

Pathfinder

On March 2, 2009, the LAS Pathfinder began its transfer from the Langley Research Center to the White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico, for launch tests. The Pathfinder is a combination of the Orion Boilerplate and LAS module. The 45 ft (14 m)-long rocket assembly will begin its first Pad Abort 1 Test on the Missile Range.[39]

Criticism

Acquisition strategy

The Space Frontier Foundation has asserted that the $3.9 billion initial phase of the Orion contract essentially duplicates the functionality of NASA's $500 million Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program.[40][41] Additionally, NASA's contract with Lockheed Martin is a cost-plus contract, a contracting method which has been criticized for being prone to cost overruns and delays, while contractors in the COTS only receive payment for successes. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) is also critical of NASA, saying, "NASA's current acquisition strategy for the CEV places the project at risk of significant cost overruns, schedule delays, and performance shortfalls because it commits the government to a long-term product development effort before establishing a sound business case."[40]

Testing

This article needs to be updated. (May 2010) |

Environmental testing

NASA performed environmental testing of Orion from 2007 to 2011 at the Glenn Research Center Plum Brook Station in Sandusky, Ohio. The Center's Space Power Facility is the world's largest thermal vacuum chamber.[42]

Abort Flight Test (AFT)

NASA will perform a series of six Abort Flight Tests between the fall of 2008 and the end of 2011 at the United States Army's White Sands Missile Range (WSMR), New Mexico.[needs update] The Orion AFT subproject includes two pad abort tests and four ascent abort tests. Three of the four ascent aborts are planned to be flown from a special test launch vehicle, the Orion Abort Test Booster, the fourth one being performed with Ares I-Y. The Orion Abort Flight Tests are similar in nature to the Little Joe II tests performed at WSMR between September 1963 and January 1966 in support of the development of the Apollo program's Launch Escape System.[43][44][45] The LAS Pathfinder boilerplate is being used.

Post-landing Orion Recovery Test (PORT)

The PORT Test is to determine and evaluate what kind of motions the astronaut crew can expect after landing. This will include conditions outside the capsule for the recovery team. The evaluation process will support NASA's design of landing recovery operations including equipment, ship and crew necessities.

The Port Test will use a full-scale boilerplate of NASA's Orion crew module and will be tested in water under simulated and real weather conditions. Tests began March 23, 2009 with a Navy-built, 18,000-pound boilerplate. It will be placed in a test pool at the Naval Surface Warfare Center's Carderock Division in West Bethesda, Md. Full sea testing will begin April 6, 2009, in a special location off the coast of NASA's Kennedy Space Center with media coverage.[46]

Schedule

NASA hopes to follow this schedule in development of the Orion:

- 2006–2007 — Engineering review of selected design

- May 6, 2010 — PA-1 (Pad Abort-1) unmanned pad abort test.[45]

- 2009 (Sep) — AA-1 (Ascent Abort-1) unmanned ascent abort test (transonic)

- 2010 (Spring) — PA-2 unmanned pad abort test

- 2010 (August) — AA-2 unmanned ascent abort test (Max Q)

- 2011 (February) — AA-3 unmanned ascent abort test (low-altitude tumble test)

- 2012 (September) — Ares I-Y unmanned ascent abort test (high altitude)

- 2014 — First unmanned flight of Orion in Earth orbit

- 2016 — First manned flight of Orion in Earth orbit.

- 2015–2018 — First unmanned flight of Altair.

- 2016–2018 First manned flight of Altair.

- 2019 First manned lunar landing with Orion/Altair system.

- 2020 Review of Mars missions

- 2031 The Mission to Mars has tentative dates

NASA initially established that it would initiate a phased retirement of the space shuttle, which would have begun with the retirement of one orbiter, Atlantis, in 2008. This decision was later changed; all three remaining shuttles would keep flying until 2010. In the meantime, NASA engineers would work to upgrade the current launch facilities to work with the next generation shuttle-derived launch vehicles.[47] Such a plan would allow lunar mission development to begin much earlier than currently planned, as additional funding will be available earlier.

Existing craft and mockup models

This is a list of the mockups that look like a whole crew module or other major component of Orion. There are other simulators that are just cockpits and smaller components, but those may be even more difficult to keep current. The flight crew module will be predominantly white (as opposed to silver).[48]

- Lockheed Martin

- Houston: Exploration Development Laboratory has a Low-Fidelity Crew Module Human Engineering Mockup

- Kennedy Space Center Operations & Checkout Facility: full scale Crew Module Pathfinder

- Michoud: Crew Module Ground Test Article is currently being built

- Denver: Lockheed Space Operations Simulation Center (SOSC) - at least one prototype

- Orbital, Dulles

- Launch Abort System Inert Vehicle

- ATK

- Launch Abort System Abort Motor

- United Space Alliance

- 1/10 scale crew module for buoyancy testing with Texas A&M-Galveston

- KSC: crew module wire frame mockup in the Human Engineering Modeling & Performance Lab

- Johnson Space Center

- Bldg 9: Medium Fidelity Crew Module

- PORT – Post-landing Orion Recovery Test (full scale) – currently at KSC, was built at Navy Carderock facility

- WEST – Water Egress Survival Trainer (1/4 scale) – Houston

- Dryden Flight Research Center

- Pad Abort 1 Flight Test Crew Module

- White Sands Missile Range

- Launch Abort System Pathfinder

- Pad Abort 1 Crew Module Pathfinder Mockup

Project Constellation nomenclature

- Orion – Crew/Service Module (CSM) manned/unmanned multi-role spacecraft.

- Altair – Lunar Surface Access Module (LSAM), the manned/unmanned lunar logistics vehicle.

- Ares I – ("The Stick") Medium-lift crew/cargo launch vehicle.[49]

- Ares IV – Medium-heavy lift launch vehicle announced in February, 2007.[50]

- Ares V – Heavy-lift cargo launch vehicle.

See also

- Atmospheric entry

- Cleon Lacefield, Orion program manager for Lockheed Martin

- Colonization of Mars

- Colonization of the Moon

- Orion Lite, proposed commercial variant of Orion from Bigelow Aerospace, intended for low earth orbit

- Prospective Piloted Transport System, Russia's proposed counterpart

- Space Exploration Vehicle

References

- ^ a b c "NASA Authorization Act of 2010". Thomas.loc.gov. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ a b c d "Preliminary Report Regarding NASA's Space Launch System and Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle" (PDF). NASA. 2011-01. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?c111:3:./temp/~c111MS7qB3::

- ^ "Orion Program Shrinking To Save Money, Time". Aviation Weekly. 19 April 2011.

- ^ Griffin, Michael (2007-01-11). "Commercial Crew & Cargo Program Overview" (PDF). 45th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting. Reno, Nevada: NASA. p. 2. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Today - President Signs NASA 2010 Authorization Act". Universetoday.com. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ "President Bush Announces New Vision for Space Exploration Program" (Press release). White House Office of the Press Secretary. 2004-01-14. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ^ a b c d e "Extending Human Presence into the Solar System" (PDF). planetary.org. 2004. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "News Conference - Exploration Systems Architecture Study" (PDF). NASA.

- ^ "NASA Selects Material for Orion Spacecraft Heat Shield". NASA.gov. 2009-04-07. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ "NASA Names New Crew Exploration Vehicle Orion" (Press release). NASA. 2006-08-22. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ Handlin, Daniel (2006-07-22). "NASA makes major design changes to CEV". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Handlin, Daniel (2006-10-11). "NASA sets Orion 13 for Moon Return". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "NASA Modifies Orion Crew Exploration Vehicle Contract". NASA.

- ^ Frank Morring, Jr. "1,000 pounds cut from Orion CEV".

- ^ a b "Orion landings to be splashdowns - KSC buildings to be demolished". NASA SpaceFlight.com. 2007-08-05. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ^ "Charter of the Review of U.S. Human Space Flight Plans Committee". NASA.gov. June 1, 2009.

- ^ "Office of Science and Technology Policy | The White House" (PDF). Ostp.gov. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ "NASA's FY 2006 Budget Proposal" (PDF). house.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-30. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ^ Berger, Brian (2006-08-31). "Lockheed Martin to Build [[NASA]]'s Orion Spaceship". space.com. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Taylor, Andrew (2005-07-22). "House Endorses Moon-to-Mars Plans". space.com. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ^ Sietzen, Jr., Frank (2005-07-24). "NASA Studying Unmanned Solution to Complete Space Station as Return to Flight Costs Grow". spaceref.com. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Cabbage, Michael (2005-07-31). "NASA outlines plans for moon and Mars". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 2010-11-23.

- ^ http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/396093main_HSF_Cmte_FinalReport.pdf

- ^ "NASA Names Orion Contractor". NASA. 2006-08-31. Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- ^ Coppinger, Rob (2006-10-06). "NASA Orion crew vehicle will use voice controls in Boeing 787-style Honeywell smart cockpit". Flight International. Retrieved 2006-10-06.

- ^ "NASA Denies Making Orion Water Landing Decision - and Deleting Touchdowns on Land". NASA Watch. 2007-08-06. Retrieved 2010-11-23.

- ^ "NASA - Orion Crew Exploration Vehicle" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. 2009-02-07. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ^ "Lockheed to build Nasa 'Moonship'". BBC News. 2006-08-31. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

- ^ "NASA Names New Crew Exploration Vehicle Orion" (Press release). NASA. 2006-08-22. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ^ "NASA Selects Material for Orion Spacecraft Heat Shield" (Press release). NASA Ames Research Center. 2009-04-07. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- ^ "NASA and ATK Successfully Deploy 18-Foot Diameter Solar Array for ST8 Program". ATK. October 9, 2008.

- ^ "The Orion Service Module". NASA. 2008-08-04. Retrieved 2008-08-19.

- ^ "Orion".

- ^ "Mission to the Moon: How We'll Go Back — and Stay This Time". popularmechanics.com. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- ^ "ATK Awarded Contract for Orion Launch Abort Motors". PRNewswire.

- ^ "Orion's New Launch Abort Motor Test Stand Ready for Action". NASA.

- ^ "NASA: Constellation Abort Test Nov 2008". Nasa.gov. 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ "NASA Orion LAS Pathfinder". Nasa.gov. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ a b Space Frontier Foundation (2006-09-01). "NASA's Rush to CEV Decision is Unnecessary and Ill-advised: Government About to Waste Billions Sending Moon Vehicle to ISS". Space Frontier Foundation Press Release. Archived from the original on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ Space Frontier Foundation (2006-07-24). "Unaffordable and Unsustainable? Signs of Failure in NASA's Earth-to-orbit Space Transportation Strategy". Space Frontier Foundation White Paper. Archived from the original on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ "NASA Glenn To Test Orion Crew Exploration Vehicle". SpaceDaily.

- ^ "RELEASE: 07-86, NASA Buys Abort Test Boosters for Orion Flight Tests". NASA.

- ^ "NASA Centers in California: Keys to the Future" (PDF). California Space Authority.

- ^ a b "Environmental Assessment for NASA Launch Abort System (LAS) Test Activities at the U.S. Army White Sands Missile Range, NM FINAL" (PDF). NASA.

- ^ "NASA Orion PORT Test". Nasa.gov. 2009-03-25. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ Sietzen, Jr., Frank (2005-07-13). "NASA and White House Discuss Early Shuttle Fleet Retirement". spaceref.com. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kylie S. Clem, (JSC-AP311) (kylie.s.clem(AT)nasa.gov), NASA employee, 4/17/09

- ^ "Big Problems With The Stick". NASAwatch.com. 2006-11-11. Retrieved 2010-12-31.

- ^ Coppinger, Rob (2007-02-01). "NASA quietly sets up budget for Ares IV lunar crew launch vehicle with 2017 test flight target". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

External links

- Official Orion NASA Web Site

- Lockheed Martin Orion Crew Vehicle Site

- Orion Crew Exploration Vehicle (July 28, 2009)

- NASA Budget Lays Out CEV Spiral Development - Aerospace Daily (Feb 4, 2004)

- Popular Mechanics article about CEV - Lockheed concept (June 2005)

- NASA Glenn to Test Orion Crew Exploration Vehicle.

- Mission to the Moon: How We'll Go Back — and Stay This Time (Popular Mechanics, March 2007)

- NASA's CGI Video of Constellation Project in Operation (Space.com)