Robert Burns: Difference between revisions

editing photo caption because info can be seen on Commons caption |

added template |

||

| Line 290: | Line 290: | ||

*{{OL_author|id=OL63008A}} |

*{{OL_author|id=OL63008A}} |

||

*[http://www.burnsscotland.com/ National Burns Collection -Scottish national archive of Burns-related portraits, manuscripts & objects] |

*[http://www.burnsscotland.com/ National Burns Collection -Scottish national archive of Burns-related portraits, manuscripts & objects] |

||

{{Robert Burns}} |

|||

{{Romanticism}} |

{{Romanticism}} |

||

{{Scots makars}} |

{{Scots makars}} |

||

Revision as of 01:16, 19 August 2011

Robert Burns | |

|---|---|

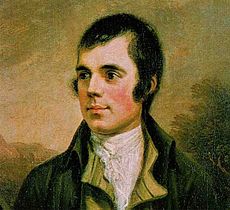

The best-known portrait of Burns | |

| Born | 25 January 1759 Alloway, Ayrshire, Scotland |

| Died | 21 July 1796 (aged 37) Dumfries, Scotland |

| Occupation | Poet, lyricist, farmer, exciseman |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Notable works | Auld Lang Syne, To a Mouse, A Man's A Man for A' That, Ae Fond Kiss, Scots Wha Hae, Tam O'Shanter, Halloween, The Battle of Sherramuir |

| Signature | |

| |

Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796) (also known as Rabbie Burns, Scotland's favourite son, the Ploughman Poet, Robden of Solway Firth, the Bard of Ayrshire and in Scotland as simply The Bard)[1][2] was a Scottish poet and a lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland, and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who have written in the Scots language, although much of his writing is also in English and a "light" Scots dialect, accessible to an audience beyond Scotland. He also wrote in standard English, and in these his political or civil commentary is often at its most blunt.

He is regarded as a pioneer of the Romantic movement, and after his death he became a great source of inspiration to the founders of both liberalism and socialism. A cultural icon in Scotland and among the Scottish Diaspora around the world, celebration of his life and work became almost a national charismatic cult during the 19th and 20th centuries, and his influence has long been strong on Scottish literature. In 2009 he was voted by the Scottish public as being the Greatest Scot, through a vote run by Scottish television channel STV.

As well as making original compositions, Burns also collected folk songs from across Scotland, often revising or adapting them. His poem (and song) Auld Lang Syne is often sung at Hogmanay (the last day of the year), and Scots Wha Hae served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem of the country. Other poems and songs of Burns that remain well-known across the world today include A Red, Red Rose; A Man's A Man for A' That; To a Louse; To a Mouse; The Battle of Sherramuir; Tam o' Shanter, and Ae Fond Kiss.

Ayrshire

Alloway

Burns was born two miles (3 km) south of Ayr, in Alloway, South Ayrshire, Scotland, the eldest of the seven children of William Burnes (1721–1784) (Robert Burns spelled his surname Burnes until 1786), a self-educated tenant farmer from Dunnottar, The Mearns, and Agnes Broun(or Brown)[3][4] (1732–1820), the daughter of a tenant farmer from Kirkoswald, South Ayrshire.

He was born in a house built by his father (now the Burns Cottage Museum), where he lived until Easter 1766, when he was seven years old. William Burnes sold the house and took the tenancy of the 70-acre (280,000 m2) Mount Oliphant farm, southeast of Alloway. Here Burns grew up in poverty and hardship, and the severe manual labour of the farm left its traces in a premature stoop and a weakened constitution.

He had little regular schooling and got much of his education from his father, who taught his children reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and history and also wrote for them A Manual Of Christian Belief. He was also taught by John Murdoch (1747–1824), who opened an 'adventure school' in Alloway in 1763 and taught Latin, French, and mathematics to both Robert and his brother Gilbert (1760–1827) from 1765 to 1768 until Murdoch left the parish. After a few years of home education, Burns was sent to Dalrymple Parish School during the summer of 1772 before returning at harvest time to full-time farm labouring until 1773, when he was sent to lodge with Murdoch for three weeks to study grammar, French, and Latin.

By the age of 15, Burns was the principal labourer at Mount Oliphant. During the harvest of 1774, he was assisted by Nelly Kilpatrick (1759–1820), who inspired his first attempt at poetry, O, Once I Lov'd A Bonnie Lass. In the summer of 1775, he was sent to finish his education with a tutor at Kirkoswald, where he met Peggy Thomson (b.1762), to whom he wrote two songs, Now Westlin' Winds and I Dream'd I Lay.

Tarbolton

Despite his ability and character, William Burns was consistently unfortunate, and migrated with his large family from farm to farm without ever being able to improve his circumstances. At Whitsun, 1777, he removed his large family from the unfavourable conditions of Mount Oliphant to the 130-acre (0.53 km2) farm at Lochlea, near Tarbolton, where they stayed until William Burnes' death in 1784. Subsequently, the family became integrated into the community of Tarbolton. To his father's disapproval, Robert joined a country dancing school in 1779 and, with Gilbert, formed the Tarbolton Bachelors' Club the following year. His earliest existing letters date from this time, when he began making romantic overtures to Alison Begbie (b. 1762). In spite of four songs written for her and a suggestion that he was willing to marry her, she rejected him.

In December 1781, Burns moved temporarily to Irvine, North Ayrshire to learn to become a flax-dresser, but during the workers' celebrations for New Year 1781/1782 (which included Burns as a participant) the flax shop caught fire and was burnt to the ground. This venture accordingly came to an end, and Burns went home to Lochlea farm.

He continued to write poems and songs and began a Commonplace Book in 1783, while his father fought a legal dispute with his landlord. The case went to the Court of Session, and Burnes was upheld in January 1784, a fortnight before he died.

Mauchline and Freemasonry

Robert and Gilbert made an ineffectual struggle to keep on the farm, but after its failure they moved to the farm at Mossgiel, near Mauchline in March, which they maintained with an uphill fight for the next four years. During the summer of 1784, Robbie came to know a group of girls known collectively as The Belles of Mauchline, one of whom was Jean Armour, the daughter of a stonemason from Mauchline.

Robert Burns was initiated into masonic Lodge St David Tarbolton on 4 July 1781, when he was 22. He was passed and raised on 1 October 1781. Later his lodge became dormant and Burns joined Lodge St James Tarbolton Kilwinning number 135. The location of the Temple where he was made a Freemason is unknown.

Although regularly meeting in Tarbolton, the "Burns Lodge" also removed itself to hold meetings in Mauchline. During 1784 he was heavily involved in Lodge business, attending all nine meetings, passing and raising brethren and generally running the Lodge. Similarly, in 1785 he was equally involved as Depute Master, where he again attended all nine lodge meetings amongst other duties of the Lodge. During 1785 he initiated and passed his brother Gilbert being raised on 1 March 1788.

At a meeting of Lodge St. Andrew in Edinburgh in 1787, in the presence of the Grand Master and Grand Lodge of Scotland, Burns was toasted by the Grand Master, Francis Chateris. In early 1787, he was feted by the Edinburgh Masonic fraternity and named the Poet Laureate of the lodge–a title which has since been accepted by Freemasonry in general.[5] The Edinburgh period of Burns's life was of great consequence, as further editions of the Kilmarnock Edition were sponsored by the Edinburgh Freemasons, ensuring that his name spread around Scotland and subsequently to England and abroad.

During his tour of the South of Scotland, as he was collecting material for The Scots Musical Museum, he visited lodges throughout Ayrshire and became an honorary member of a number of them. On his journey home to Ayrshire, he passed through Dumfries (where he later lived).

On 25 July 1787, after being re-elected Depute Master, he presided at a meeting where several well-known Masons were given honorary membership. During his Highland tour, he visited many other lodges. During the period from his election as Depute Master in 1784, Lodge St James had been convened 70 times. Burns was present 33 times and was 25 times the presiding officer.

He joined Lodge Dumfries St Andrew Number 179 on 27 December 1788. Out of the six Lodges in Dumfries, this was the weakest. The records of this lodge are scant, and no more is heard of him until 30 November 1792, when Burns was elected Senior Warden. From this date until his final meeting in the Lodge on 14 April 1796, it appears that the Lodge met only five times.

On 28 August 1787, Burns visited Stirling and passed through Bridge of Allan on his way to the Roman fort at Braco. In 1793, he wrote his poem By Allan Stream.[6]

Love affairs

His casual love affairs did not endear him to the elders of the local kirk and created for him a reputation for dissoluteness amongst his neighbours. His first child, Elizabeth Paton Burns (1785–1817), was born to his mother's servant, Elizabeth Paton (1760-circa 1799), while he was embarking on a relationship with Jean Armour, who became pregnant with twins in March 1786. Burns signed a paper attesting his marriage to Jean, but her father "was in the greatest distress, and fainted away." To avoid disgrace, her parents sent her to live with her uncle in Paisley. Although Armour's father initially forbade it, they were eventually married in 1788.[7] Armour bore him nine children, but only three survived infancy.

Burns was in financial difficulties due to his want of success in farming, and to make enough money to support a family he took up a friend's offer of work in Jamaica, at a salary of £30 per annum.[8][9] The position that Burns accepted was as a bookkeeper on a slave plantation. This seems inconsistent with Burns' egalitarian views as typified by his writing of The Slave's Lament six years later, but in 1786 there was little public awareness of the abolitionism movement which began about that time.[10][11]

At about the same time, Burns had fallen in love with Mary Campbell (1763–1786), whom he had seen in the church while he was still living in Tarbolton. She was born near Dunoon and had lived in Campbeltown before moving to work in Ayrshire. He dedicated the poems The Highland Lassie O, Highland Mary and To Mary in Heaven to her. His song "Will ye go to the Indies. my Mary, And leave auld Scotia's shore?" suggests that they planned to emigrate to Jamaica together. Their relationship has been the subject of much conjecture, and it has been suggested that on 14 May 1786 they exchanged Bibles and plighted their troth over the Water of Fail in a traditional form of marriage. Soon afterwards Mary Campbell left her work in Ayrshire, went to the seaport of Greenock, and sailed home to her parents in Campbeltown.[8][9]

Kilmarnock Edition

As Burns lacked the funds to pay for his passage to the West Indies, Gavin Hamilton suggested that he should "publish his poems in the mean time by subscription, as a likely way of getting a little money to provide him more liberally in necessaries for Jamaica". On 3 April Burns sent proposals for publishing his "Scotch Poems" to John Wilson, a local printer in Kilmarnock, who published these proposals on 14 April 1786, on the same day that Jean Armour's father tore up the paper in which Burns attested his marriage to Jean. To obtain a certificate that he was a free bachelor, Burns agreed on 25 June to stand for rebuke in Mauchline kirk for three Sundays. He transferred his share in Mossgiel farm to his brother Gilbert on 22 July, and on 30 July wrote to tell his friend John Richmond that "Armour has got a warrant to throw me in jail until I can find a warrant for an enormous sum ... I am wandering from one friend's house to another".[12]

On 31 July 1786 John Wilson published the volume of works by Robert Burns, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish dialect.[13] Known as the Kilmarnock volume, it sold for 3 shillings and contained much of his best writing, including The Twa Dogs; Address to the Deil; Halloween; The Cotter's Saturday Night; To a Mouse; Epitaph for James Smith and To a Mountain Daisy, many of which had been written at Mossgiel farm. The success of the work was immediate, and soon he was known across the country.

Burns postponed his proposed emigration to Jamaica on 1 September, and was at Mossgiel two days later when he learnt that Jean Armour had given birth to twins. On 4 September Thomas Blacklock wrote a letter expressing admiration for the poetry in the Kilmarnock volume, and suggesting an enlarged second edition.[13] A copy of it was passed to Burns, who later recalled, "I had taken the last farewell of my few friends, my chest was on the road to Greenock; I had composed the last song I should ever measure in Scotland–'The Gloomy night is gathering fast'–when a letter from Dr Blacklock to a friend of mine overthrew all my schemes, by opening new prospects to my poetic ambition. The Doctor belonged to a set of critics for whose applause I had not dared to hope. His opinion that I would meet with encouragement in Edinburgh for a second edition, fired me so much, that away I posted for that city, without a single acquaintance, or a single letter of introduction."[14]

In October, Mary Campbell (Highland Mary) and her father sailed from Campbeltown to visit her brother in Greenock. Her brother fell ill with typhus, which she also caught while nursing him. She died of typhus on 20 or 21 October 1786, and was buried there.[9]

Edinburgh

On 27 November 1786, Burns borrowed a pony and set out for Edinburgh. On 14 December William Creech issued subscription bills for the first Edinburgh edition of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish dialect, which was published on 17 April 1787. Within a week of this event, Burns had sold his copyright to Creech for 100 guineas.[13] In Edinburgh, he was received as an equal by the city's brilliant men of letters—including Dugald Stewart, Robertson, Blair and others—and was a guest at aristocratic gatherings, where he bore himself with unaffected dignity. Here he encountered, and made a lasting impression on, the 16-year-old Walter Scott, who described him later with great admiration:

His person was strong and robust; his manners rustic, not clownish, a sort of dignified plainness and simplicity which received part of its effect perhaps from knowledge of his extraordinary talents. His features are presented in Mr Nasmyth's picture but to me it conveys the idea that they are diminished, as if seen in perspective. I think his countenance was more massive than it looks in any of the portraits ... there was a strong expression of shrewdness in all his lineaments; the eye alone, I think, indicated the poetical character and temperament. It was large, and of a dark cast, and literally glowed when he spoke with feeling or interest. I never saw such another eye in a human head, though I have seen the most distinguished men of my time.

— Walter Scott

The new edition of his poems brought Burns £400. His stay in the city also resulted in some lifelong friendships, among which were those with Lord Glencairn, and Frances Anna Dunlop (1730–1815), who became his occasional sponsor and with whom he corresponded for many years until a rift developed. He embarked on a relationship with the separated Agnes 'Nancy' McLehose (1758–1841), with whom he exchanged passionate letters under pseudonyms (Burns called himself 'Sylvander' and Nancy 'Clarinda'). When it became clear that Nancy would not be easily seduced into a physical relationship, Burns moved on to Jenny Clow (1766–1792), Nancy's domestic servant, who bore him a son, Robert Burns Clow in 1788. His relationship with Nancy concluded in 1791 with a final meeting in Edinburgh before she sailed to Jamaica for what transpired to be a short-lived reconciliation with her estranged husband. Before she left, he sent her the manuscript of Ae Fond Kiss as a farewell to her.

In Edinburgh, in early 1787, he met James Johnson, a struggling music engraver and music seller with a love of old Scots songs and a determination to preserve them. Burns shared this interest and became an enthusiastic contributor to The Scots Musical Museum. The first volume of this was published in 1787 and included three songs by Burns. He contributed 40 songs to volume 2, and would end up responsible for about a third of the 600 songs in the whole collection, as well as making a considerable editorial contribution. The final volume was published in 1803.

Dumfries

Ellisland Farm

On his return to Ayrshire on 18 February 1788, he resumed his relationship with Jean Armour and took a lease on the farm of Ellisland near Dumfries on 18 March (settling there on 11 June) but trained as a Gauger, or in English, an exciseman; should farming continue to prove unsuccessful. He was appointed duties in Customs and Excise in 1789 and eventually gave up the farm in 1791. Meanwhile, he was writing at his best, and in November 1790 had produced Tam O' Shanter. About this time he was offered and declined an appointment in London on the staff of 'The Star' newspaper,[15] and refused to become a candidate for a newly-created Chair of Agriculture in the University of Edinburgh,[15] although influential friends offered to support his claims.

Lyricist

After giving up his farm he removed to Dumfries itself. Burns described the Globe Inn (still running today) on the High Street as his "favourite howff" (or "inn").

It was at this time that, being requested to write lyrics for The Melodies of Scotland, he responded by contributing over 100 songs. He made major contributions to George Thomson's A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice as well as to James Johnson's The Scots Musical Museum. Arguably his claim to immortality chiefly rests on these volumes which placed him in the front rank of lyric poets. Burns described how he had to master singing the tune before he composed the words:

My way is: I consider the poetic sentiment, correspondent to my idea of the musical expression, then chuse my theme, begin one stanza, when that is composed - which is generally the most difficult part of the business - I walk out, sit down now and then, look out for objects in nature around me that are in unison or harmony with the cogitations of my fancy and workings of my bosom, humming every now and then the air with the verses I have framed. when I feel my Muse beginning to jade, I retire to the solitary fireside of my study, and there commit my effusions to paper, swinging, at intervals, on the hind-legs of my elbow chair, by way of calling forth my own critical strictures, as my, pen goes.

— Robert Burns

Burns also worked to collect and preserve Scottish folk songs, sometimes revising, expanding, and adapting them. One of the better known of these collections is The Merry Muses of Caledonia (the title is not Burns'), a collection of bawdy lyrics that were popular in the music halls of Scotland as late as the 20th century. Many of Burns' most famous poems are songs with the music based upon older traditional songs. For example, Auld Lang Syne is set to the traditional tune Can Ye Labour Lea, A Red, Red Rose is set to the tune of Major Graham and The Battle of Sherramuir is set to the Cameronian Rant.

Failing health and death

Burns's worldly prospects were now perhaps better than they had ever been; but he had become soured, and moreover had alienated many of his best friends by too freely expressing sympathy with the French Revolution, and the then unpopular advocates of reform at home. As his health began to give way, he began to age prematurely and fell into fits of despondency. The habits of intemperance (alleged mainly by temperance activist James Currie[16]) are said to have aggravated his long-standing possible rheumatic heart condition.[17] His death followed a dental extraction in winter 1795.

On the morning of 21 July 1796, Robert Burns died in Dumfries at the age of 37. The funeral took place on Monday 25 July 1796, also the day that his son Maxwell was born. He was at first buried in the far corner of St. Michael's Churchyard in Dumfries; his body was eventually moved in September 1815 to its final resting place, in the same cemetery, the Burns Mausoleum. Jean Armour was laid to rest with him in 1834.[17]

His widow, Jean, had taken steps to secure his movable estate, partly by liquidating two promissory notes amounting to fifteen pounds sterling (about 1,100 pounds at 2009 prices).[18] The family went to the Court of Session in 1798 with a scheme to support his surviving children by publishing a four-volume edition of his complete works and a biography written by Dr. James Currie. Subscriptions were raised to meet the initial cost of publication, which was in the hands of Thomas Cadell and William Davies in London and William Creech, bookseller in Edinburgh.[19] Hogg records that fund-raising for Burns' family was embarrassingly slow, and it took several years to accumulate significant funds through the efforts of John Syme and Alexander Cunningham.[17]

Burns was posthumously given the freedom of the town.[16] Hogg records that Burns was given the freedom of the Burgh of Dumfries on 4 June 1787, years before his death, and was also made an Honorary Burgess of Dumfries.[20]

Literary style

The style of Burns is marked by spontaneity, directness, and sincerity, and his variety ranges from the tender intensity of some of his lyrics through the rollicking humour and blazing wit of Tam o' Shanter to the blistering satire of Holy Willie's Prayer and The Holy Fair.

Burns' poetry drew upon a substantial familiarity and knowledge of Classical, Biblical, and English literature, as well as the Scottish Makar tradition.[21] Burns was skilled in writing not only in the Scots language but also in the Scottish English dialect of the English language. Some of his works, such as Love and Liberty (also known as The Jolly Beggars), are written in both Scots and English for various effects.[22]

His themes included republicanism (he lived during the French Revolutionary period) and Radicalism which he expressed covertly in Scots Wha Hae, Scottish patriotism, anticlericalism, class inequalities, gender roles, commentary on the Scottish Kirk of his time, Scottish cultural identity, poverty, sexuality, and the beneficial aspects of popular socialising (carousing, Scotch whisky, folk songs, and so forth).[23]

The strong emotional highs and lows associated with many of Burns' poems have led some, such as Burns biographer Robert Crawford,[24] to suggest that he suffered from manic depression—a hypothesis that has been supported by analysis of various samples of his handwriting. Burns himself referred to suffering from episodes of what he called "blue devilism". However, the National Trust for Scotland has downplayed the suggestion on the grounds that the evidence is not sufficient to support the claim.[25] While Burns's life was troubled and his character was flawed in many ways, he fought at tremendous odds. As Thomas Carlyle puts it in his Essay:

Granted the ship comes into harbour with shrouds and tackle damaged, the pilot is blameworthy... but to know how blameworthy, tell us first whether his voyage has been round the Globe or only to Ramsgate and the Isle of Dogs.

Gallery

-

Robert Burns statue sculpted by Sir John Steell, unveiled in Central Park, New York in 1880.

-

Bronze statue of Burns erected in Dundee in 1880. A companion statue from the same cast as the New York statue.

-

Statue of Burns by Henry Bain Smith 1892, Union Terrace Gardens in Aberdeen

-

Statue of Burns erected by Clement Wilson at Eglinton Country Park, North Ayrshire.

Scotland and England

He is generally classified as a proto-Romantic poet, and he influenced William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Percy Bysshe Shelley greatly. His direct literary influences in the use of Scots in poetry were Allan Ramsay (1686-1758) and Robert Fergusson. The Edinburgh literati worked to sentimentalise Burns during his life and after his death, dismissing his education by calling him a "heaven-taught ploughman". Burns would influence later Scottish writers, especially Hugh MacDiarmid, who fought to dismantle what he felt had become a sentimental cult that dominated Scottish literature.

United States

An example of the Burns literary influence in the U.S. is the novelist John Steinbeck, who took the title of his 1937 novel Of Mice and Men from a line contained in the second-to-last stanza of To a Mouse: "The best laid schemes o' mice an' men / Gang aft agley". Burns' influence on American vernacular poets such as James Whitcomb Riley and Frank Lebby Stanton has been acknowledged by their biographers.[26] When asked for the source of his greatest creative inspiration, singer songwriter Bob Dylan selected Burns's 1794 song A Red, Red Rose, as the lyric that had the biggest effect on his life.[27][28] The author J. D. Salinger used protagonist Holden Caulfield's misinterpretation of Burns' poem Comin' Through the Rye as his title and a main interpretation of Holden's grasping to his childhood in his 1951 novel The Catcher in the Rye. The poem, actually about a rendezvous, is thought by Holden to be about saving people from falling out of childhood.[29]

Russia

Burns became the "people's poet" of Russia. In Imperial times, the Russian aristocracy were so out of touch with the peasantry that Burns, translated into Russian, became a symbol for the ordinary Russian people. In Soviet Russia, Burns was elevated as the archetypal poet of the people. A new translation of Burns, begun in 1924 by Samuil Marshak, proved enormously popular, selling over 600,000 copies.[30]

The Soviet Union was the first country in the world to honour Burns with a commemorative stamp in 1956. The poetry of Burns is taught in Russian schools alongside their own national poets. Burns was a great admirer of the egalitarian ethos behind the French Revolution, and that was an additional reason for the Communist regime to endorse him as a "progressive" artist. He has remained popular in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union as well.[31]

Honours

Landmarks and organisations

Burns clubs have been founded worldwide. The first one, known as The Mother Club, was founded in Greenock in 1801 by merchants born in Ayrshire, some of whom had known Burns. The club set its original objectives as "To cherish the name of Robert Burns; to foster a love of his writings, and generally to encourage an interest in the Scottish language and literature." The club also continues to have local charitable work as a priority.[32]

Burns' birthplace in Alloway is now a public museum known as Burns Cottage. His house in Dumfries is operated as the Robert Burns House, and the Robert Burns Centre in Dumfries features more exhibits about his life and works. Ellisland Farm in Auldgirth, which he owned from 1788 to 1791, is a museum and working farm.

Significant 19th-century monuments to him stand in Alloway, Edinburgh and Dumfries. An early 20th century replica of his birthplace cottage belonging to the Burns Club Atlanta stands in Atlanta, Georgia. These are part of a large list of Robert Burns memorials and statues around the world.

Organisations include the Robert Burns Fellowship of the University of Otago in New Zealand, and the Burns Club Atlanta in the United States. Towns named after Robert Burns include Burns, New York, and Burns, Oregon.

In the suburb of Summerhill, Dumfries, the majority of the streets have names with Burns connotations. A BR Standard Class 7 steam locomotive was named after him, along with a later British Rail Class 87 electric locomotive, No.87035.

On 24 September 1996, class 156 diesel unit 156433 was named "The Kilmarnock Edition" by Jimmy Knapp, General Secretary of the RMT union, at Girvan Station to launch the new 'Burns Line' services between Girvan, Ayr and Kilmarnock, supported by Strathclyde Passenger Transport (SPT). In the vestibule behind the cycle racks there was a poster explaining the significance of the naming.

Several streets surrounding the Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.'s Back Bay Fens in Boston, Massachusetts were designed with Burns connotations. A life size statue was dedicated in Burn's honor within the Back Bay Fens of the West Fenway neighborhood in 1912. It stood until 1972 when it was relocated downtown, sparking protests from the neighborhood, literary fans, and preservationists of Olmsted's vision for the Back Bay Fens.

The Friends of Ellisland maintain Ellisland Farm as a museum and interpretation centre.

There is a statue of Robert Burns in the Octagon in Dunedin, New Zealand. A crater on Mercury is named after him.

Stamps and currency

The Soviet Union was the first country in the world to honour Burns with a commemorative stamp, marking the 160th anniversary of his death in 1956.[33]

The Royal Mail has issued postage stamps commemorating Burns three times. In 1966, two stamps were issued, priced fourpence and 1 shilling and threepence, both carrying Burns' portrait. In 1996, an issue commemorating the bicentenary of his death comprised four stamps, priced 19 p, 25 p, 41 p and 60 p, and included quotes from Burns' poems. On 22 January 2009, two stamps were issued by the Royal Mail to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Burns' birth.

Burns is pictured on the £5 banknote (since 1971) of the Clydesdale Bank, one of the Scottish banks with the right to issue banknotes.[34] On the reverse of the note there is a vignette of a field mouse and a wild rose which refers to Burns' poem To a Mouse. In September 2007, the Bank of Scotland redesigned their banknotes, and Robert Burns' statue is now portrayed on the reverse side of new £5.[35]

In 2009, the Royal Mint issued a commemorative two pound coin featuring a quote from "Auld Lang Syne".[36]

Musical tributes

In 1996, a musical called Red Red Rose won third place at a competition for new musicals in Denmark. The musical was about Burns' life, and he was played by John Barrowman. On 25 January 2008, a musical play about the love affair between Robert Burns and Nancy McLehose entitled "Clarinda", premiered in Edinburgh before touring Scotland.[37]

Burns suppers

Burns Night, effectively a second national day, is celebrated on 25 January with Burns suppers around the world, and is still more widely observed than the official national day, St. Andrew's Day. The first Burns supper in The Mother Club in Greenock was held on what they thought was his birthday on 29 January 1802, but in 1803 they discovered from the Ayr parish records that the correct date was 25 January 1759.[32] The format of Burns suppers has not changed since. The basic format starts with a general welcome and announcements, followed with the Selkirk Grace. After the grace, comes the piping and cutting of the haggis, where Burns' famous Address To a Haggis is read and the haggis is cut open. The event usually allows for people to start eating just after the haggis is presented. This is when the reading called the "immortal memory", an overview of Burns' life and work, is given; the event usually concludes with the singing of Auld Lang Syne.

Greatest Scot

In 2009, STV ran a television series and public vote to decide who should be named as being the Greatest Scot. On St Andrew's day, STV revealed the results of the public vote, and Robert Burns was voted as being officially the Greatest Scot of all time, narrowly beating William Wallace, Scottish patriot and independence campaigner, for the title.[38]

See also

Notes

- ^ Andrew O'Hagan, "The People's Poet", The Guardian, 19 January 2008.

- ^ "Scotland's National Bard". Robert Burns 2008. Scottish Executive. 25 January 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ "Burnes, William". The Burns Encyclopedia. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ "Robert Burns 1759 - 1796". The Robert Burns World Federation. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ "A successor to Robert Burns; crowning the Poet-Laureate of Freemasonry" (PDF). New York Times. 18 December 1884. p. 2. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ Stream, Allan. "Rabbie Burns". Kilronan House. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ "Mauchline kirk session records, National Archives of Scotland". 'The Legacy of Robert Burns' feature on the National Archives of Scotland website. National Archives of Scotland. 1 July 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ^ a b Burns 1993, p. 19

- ^ a b c "Highland Mary (Mary Campbell)". Famous Sons and Daughters of Greenock. Nostalgic Greenock. Retrieved 17 January 2010. [dead link]

- ^ "Feature on The Poet Robert Burns". Robert Burns History. Scotland.org. 13 January 2004. Retrieved 10 June 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Folkin' For Jamaica: Sly, Robbie and Robert Burns". The Play Ethic. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ Burns 1993, pp. 19–20

- ^ a b c Burns 1993, p. 20

- ^ Robert Chambers, ed. (1856). "Significant Scots - Thomas Blacklock". Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen. Blackie and Son. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Robert Burns: "Poetry - Poems - Poets." Retrieved on 24 September 2010

- ^ a b Robert Burns: "The R.B. Gallery." Retrieved on 24 September 2010

- ^ a b c Hogg, Patrick Scott (2008). Robert Burns. The Patriot Bard. Edinburgh : Mainstream Publishing. ISBN. 978-1-84596-412-2. p. 321.

- ^ "Testament Dative and Inventory of Robert Burns, 1796, Dumfries Commissary Court (National Archives of Scotland CC5/6/18, pp. 74-75)". ScotlandsPeople website. National Archives of Scotland. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ^ "Appointment of judicial factor for Robert Burns' children, Court of Session records (National Archives of Scotland CS97/101/15), 1798-1801". 'The Legacy of Robert Burns' feature on the National Archives of Scotland website. National Archives of Scotland. 1 July 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ^ Hogg, Patrick Scott (2008). Robert Burns. The Patriot Bard. Edinburgh : Mainstream Publishing. ISBN. 978-1-84596-412-2. p. 154.

- ^ Robert Burns: "Literary Style." Retrieved on 24 September 2010

- ^ Robert Burns: "some hae meat." Retrieved on 24 September 2010

- ^ Red Star Cafe: "Address to the Kibble." Retrieved on 24 September 2010

- ^ Rumens, Carol (16 January 2009). "The Bard, By Robert Crawford". Books. London: The Independent. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ Watson, Jeremy (7 June 2009). "Bard in the hand: Trust accused of hiding Burns' mental illness". Scotland on Sunday. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ See, e.g., Paul Stevenson, "Stanton—the Writer with a Heart" in Atlanta Constitution, 1925 January 18, p. 1; republished by Perry, L.L.; Wightman, Melton F. (1938), Frank Lebby Stanton: Georgia's First Post Laureate, Atlanta: Georgia State Department of Education., pp. 8–14

- ^ Simpson, Richard (5 October 2008). "Bob Dylan names Scottish poet Robert Burns as his biggest inspiration". London: Daily Mail. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

Bob Dylan has named his own greatest inspiration as the Scottish poet Robert Burns. The American singer-songwriter was asked to say which lyric or verse has had the biggest effect on his life. He selected the 1794 song "A Red, Red Rose", which is often published as a poem, penned by the man regarded as Scotland's national poet.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Michaels, Sean (6 October 2008). "Bob Dylan: Robert Burns is my biggest inspiration". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

Dylan has revealed his greatest inspiration is Scotland's favourite son, the Bard of Ayrshire, the 18th-century poet known to most as Rabbi Burns. Dylan selected A Red, Red Rose, written by Burns in 1794.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "J. D. Salinger's Catcher in the Rye". Sparknotes. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

When [holden] tries to explain why he hates school, she accuses him of not liking anything. He tells her his fantasy of being "the catcher in the rye," a person who catches little children as they are about to fall off of a cliff. Phoebe tells him that he has misremembered the poem that he took the image from: Robert Burns's poem says "if a body meet a body, coming through the rye," not "catch a body."

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Burns Biography". Standrews.com. 27 January 1990. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ Trew, Jonathan (10 April 2005). "From Rabbie with love". Scotsman.com Heritage & Culture. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ a b "Congratulation Greenock Burns Club". The Robert Burns World Federation Limited. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ^ Robert Burns World Federation Limited Burns chronicle, Volume 4, Issue 3 p.27. Burns Federation, 1995

- ^ "Current Banknotes : Clydesdale Bank". The Committee of Scottish Clearing Bankers. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ^ "Current Banknotes : Bank of Scotland". The Committee of Scottish Clearing Bankers. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ^ "The 2009 Robert Burns £2 Coin Pack". Retrieved 5 January 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Clarinda - The Musical - No woman shunned Robert Burns' advances, until he met Clarinda !". Clarindathemusical.com. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ Robert Burns voted Greatest Scot STV. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

References

- Burns, Robert (1993). Bold, Alan (ed.). Rhymer Rab: An Anthology of Poems and Prose. London: Black Swan. ISBN 1-84195-380-6.

- Burns, Robert (2003). Noble, Andrew; Hogg, Patrick Scott (eds.). The Canongate Burns: The Complete Poems and Songs of Robert Burns. Edinburgh: Canongate Books. ISBN 1-84195-380-6.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource. (p.57)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource. (p.57)- Dietrich Hohmann: Ich, Robert Burns, Biographical Novel, Neues Leben, Berlin 1990 (in German)

External links

- Official site of Burns Cottage Museum

- Works by Robert Burns at Project Gutenberg

- National Library of Scotland's Burns site

- "Archival material relating to Robert Burns". UK National Archives.

- Legacy of Robert Burns - National Archives of Scotland website

- Works by Robert Burns at Open Library

- National Burns Collection -Scottish national archive of Burns-related portraits, manuscripts & objects

- Use dmy dates from February 2011

- Robert Burns

- 1759 births

- 1796 deaths

- 18th-century Scottish people

- Infectious disease deaths in Scotland

- Lallans poets

- People from South Ayrshire

- People illustrated on sterling banknotes

- Romantic poets

- Scottish folk-song collectors

- Scottish literature

- Scottish poets

- Scottish songwriters