Basque Country (greater region): Difference between revisions

→Territorial extension: put the link where it belongs |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 182: | Line 182: | ||

==== Political status and violence ==== |

==== Political status and violence ==== |

||

[[Image:Flag of the Basque Country.svg|thumb|The [[Ikurrina]], the official flag of the Basque [[Autonomous Community]], also used informally in Navarre, the French Basque country and abroad]] |

[[Image:Flag of the Basque Country.svg|thumb|The [[Ikurrina]], the official flag of the Basque [[Autonomous Community]], also used informally in Navarre, the French Basque country and abroad]] |

||

Since the 19th century, [[Basque nationalism]] has demanded the right of some kind of [[self-determination]]{{Citation needed|date=January 2008}}, which is supported by 60% of Basques in the Basque Autonomous Community, and [[independence]], which would be supported in this same territory, according to a poll, by approximately 25%<ref>[http://www.elpais.com/articulo/espana/Solo/25/vascos/apoya/independencia/sondeo/Gobierno/Vitoria/elpporesp/20021225elpepunac_1/Tes http://www.elpais.com/articulo/espana/Solo/25/vascos/apoya/independencia/sondeo/Gobierno/Vitoria/elpporesp/20021225elpepunac_1/Tes] ''elpais.com''</ref> of them, the 5% decrease from the previous poll suggesting that the desire for independence is steadily decreasing. This desire for independence is particularly stressed among [[left-wing politics|leftist]] Basque nationalists. The right of self-determination was asserted by the [[Basque Parliament]] in 1990, 2002 and 2006.<ref>[http://www.eitb24.com/portal/eitb24/noticia/en/politics/pp-and-pse-voted-against-basque-parliament-adopts-resolution-on-s?itemId=B24_18787&cl=%2Feitb24%2Fpolitica&idioma=en EITB: ''Basque parliament adopts resolution on self-determination'']</ref> |

Since the 19th century, [[Basque nationalism]] ([[abertzale]]ak) has demanded the right of some kind of [[self-determination]]{{Citation needed|date=January 2008}}, which is supported by 60% of Basques in the Basque Autonomous Community, and [[independence]], which would be supported in this same territory, according to a poll, by approximately 25%<ref>[http://www.elpais.com/articulo/espana/Solo/25/vascos/apoya/independencia/sondeo/Gobierno/Vitoria/elpporesp/20021225elpepunac_1/Tes http://www.elpais.com/articulo/espana/Solo/25/vascos/apoya/independencia/sondeo/Gobierno/Vitoria/elpporesp/20021225elpepunac_1/Tes] ''elpais.com''</ref> of them, the 5% decrease from the previous poll suggesting that the desire for independence is steadily decreasing. This desire for independence is particularly stressed among [[left-wing politics|leftist]] Basque nationalists. The right of self-determination was asserted by the [[Basque Parliament]] in 1990, 2002 and 2006.<ref>[http://www.eitb24.com/portal/eitb24/noticia/en/politics/pp-and-pse-voted-against-basque-parliament-adopts-resolution-on-s?itemId=B24_18787&cl=%2Feitb24%2Fpolitica&idioma=en EITB: ''Basque parliament adopts resolution on self-determination'']</ref> |

||

Since{{Citation needed|date=January 2008}} self-determination is not recognized in the [[Spanish Constitution of 1978]], some Basques abstained and some even voted against it in the referendum of December 6 of that year. However, it was approved by a clear [[majority]] at the Spanish level, and simple majority at Navarrese and Basque levels. The derived autonomous regimes for the BAC was approved in later referendum but the autonomy of Navarre (''amejoramiento del fuero'': "improvement of the charter") was never subject to referendum but just approved by the Navarrese Cortes (parliament). |

Since{{Citation needed|date=January 2008}} self-determination is not recognized in the [[Spanish Constitution of 1978]], some Basques abstained and some even voted against it in the referendum of December 6 of that year. However, it was approved by a clear [[majority]] at the Spanish level, and simple majority at Navarrese and Basque levels. The derived autonomous regimes for the BAC was approved in later referendum but the autonomy of Navarre (''amejoramiento del fuero'': "improvement of the charter") was never subject to referendum but just approved by the Navarrese Cortes (parliament). |

||

There are not many sources on the issue for the French Basque country. |

There are not many sources on the issue for the French Basque country. |

||

Revision as of 11:04, 26 August 2011

Basque Country Euskal Herria | |

|---|---|

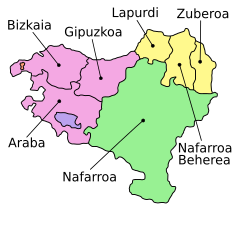

Location of the Basque Country | |

The seven provinces of the Basque Country, as claimed by certain Basque sectors, span France (light yellow) and Spain (rest of the map). The enclaves of Valle de Villaverde and Treviño are pictured in red and blue, respectively. Names on this map are in Basque. | |

| Largest city | Bilbao |

| Official languages | Basque, Spanish, French |

| Area | |

• Total | 20,947 km2 (8,088 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Estimate | about 3,000,000 |

- Not to be confused with some of its homonyms constituent parts: the autonomous community of the Basque Country in Spain, and the Northern Basque Country in France.

The Basque Country (Template:Lang-eu) is the name given to the home of the Basque people in the western Pyrenees that spans the border between France and Spain on the Atlantic coast.

It comprises the Autonomous Communities of the Basque Country and Navarre in Spain and the Northern Basque Country in France.

Even though they are not necessarily synonyms, the concept of a single culturally Basque area spanning various regions and countries has been closely associated since its very inception to the politics of Basque nationalism. As such, the region is considered home to the Basque people (Template:Lang-eu), their language (Template:Lang-eu), culture and traditions. Nevertheless the area is neither linguistically nor culturally homogeneous, and the very Basqueness of parts of it, such as southern Navarre, remains a very contentious issue.

Territorial extension

The modern claim for the extent of the Basque Country, coined in the nineteenth century, is seven traditional regions. Some Basques refer to the seven regions collectively as Zazpiak Bat, meaning "The Seven [are] One".

Spanish Basque Country

The Spanish Basque Country (Template:Lang-es, Template:Lang-eu) includes two main regions: the Basque Autonomous Community (capital: Vitoria-Gasteiz) and the Chartered Community of Navarre (capital: Pamplona).

The Basque Autonomous Community (7,234 km²)[1] consists of three provinces, specifically designated "historical territories":

- Álava (capital: Vitoria-Gasteiz)

- Biscay (capital: Bilbao)

- Gipuzkoa (capital: Donostia-San Sebastián)

In addition, some sources consider two enclaves as part of the Basque Autonomous Community:[2]

- Enclave of Treviño (280 km²),[3] a Castilian enclave in Álava

- Valle de Villaverde (20 km²), a Cantabrian enclave in Biscay

The Chartered Community of Navarre (10,391 km²)[1] is a uniprovincial autonomous community. Its name refers to the medieval charters, the Fueros of Navarre. The Spanish Constitution of 1978 states that Navarre may become a part of the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country if it was so decided by its people and institutions. To date, the results of regional elections have shown a clear rejection of this option. The ruling Navarrese People's Union has repeatedly asked for an amendment to the Constitution in order to remove this clause.[4]

French Basque Country

The French Basque Country (Basque: Iparralde) is the western part of the French département of Pyrénées Atlantiques. In most contemporary sources it covers the arrondissement of Bayonne and the cantons of Mauléon-Licharre and Tardets-Sorholus, but sources disagree on the status of the village of Esquiule.[5] Within these conventions, the area of Northern Basque Country (including the 29 km² of Esquiule) is 2,995 km².[6]

The French Basque Country is traditionally subdivided into three provinces:

- Labourd, historical capital Ustaritz, main settlement today Bayonne

- Lower Navarre, historical capitals Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and Saint-Palais, main settlement today Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port

- Soule, historical capital Mauléon (also current main settlement)

However, this summary presentation makes it hard to justify the inclusion of a few communes in the lower Adour region. As emphasized by Jean Goyhenetche, it would be more accurate to depict it as the reunion of five entities: Labourd, Lower Navarre, Soule but also Bayonne and Gramont.[7]

History

According to some theories, Basques may be the least assimilated remnant of the Paleolithic inhabitants of Western Europe (specifically those of the Franco-Cantabrian region) to the Indo-European migrations. Basque tribes were mentioned by Roman writers Strabo and Pliny, including the Vascones, the Aquitani and others. There is considerable evidence to show their Basque ethnicity in Roman times in the form of place-names, Caesar's reference to their customs and physical make-up, the so-called Aquitanian inscriptions recording names of people and gods (approx. 1st century, see Aquitanian language), etc.

Geographically, the Basque Country was inhabited in Roman times by several tribes, i.e. the Vascones, the Varduli, the Caristi, the Autrigones, the Berones, the Tarbelli and the Sibulates. While we are led to think that except for the Berones and Autrigones they were non-Indo-European peoples, the ethnic background of the most westerly tribes is not clear due to the lack of evidence. Some ancient place-names, such as Deba, Butrón, Nervión, Zegama, suggest the presence of non-Basque peoples at this point of protohistory. The ancient tribes are last cited in the 5th century, after which track of them is lost and only Vascones are still accounted for, but even far beyond their former boundaries, e.g. in the current lands of Álava.

The Cantabri, encompassing probably present-day Biscay, Cantabria, Burgos and at least part of Álava and La Rioja, lived to the west of Vascon territory in the Early Middle Ages, but the ethnic nature of this people often at odds with and finally overcome by the Visigoths is not certain. The Vascones around Pamplona, after much fighting against Franks and Visigoths, founded the Kingdom of Pamplona (824), inextricably linked to their kinsmen the Banu Qasi. All other tribes in the Iberian Peninsula had been, to a great extent, linguistically and culturally assimilated by Roman culture and language by the end of the Roman period or early period of the Early Middle Ages (ethnic Basques extended well east into the lands around the Pyrenees until the 9-11 centuries though).

In the Early Middle Ages (up to the 9-10th centuries) the territory between the Ebro and Garonne rivers was known as Vasconia, a blur ethnic area and polity struggling to fend off the pressure of the Iberian Visigothic kingdom and Muslim rule on the south and the Frankish push on the north. By the turn of the millennium, after Muslim invasions and Frankish expansion under Charlemagne, the territory of Vasconia (to become Gascony) fragmented into different feudal regions, e.g. the viscountcies of Soule and Labourd out of former tribal systems and minor realms (County of Vasconia), while south of the Pyrenees, besides the above Kingdom of Pamplona, Gipuzkoa, Álava and Biscay arose in the current lands of the Southern Basque Country from the 9th century and onwards.

These westerly territories pledged allegiance (though intermittently) to Navarre in their early stages, but they were annexed to the Kingdom of Castile at the end of the 12th century, so depriving the Kingdom of Navarre of direct access to the ocean. In the Late Middle Ages, important families dotting the whole Basque territory came to prominence, often quarrelling with each other for power and unleashing the bloody War of the Bands, only stopped by royal intervention and the gradual shift of power from the countryside to the towns by the 16th century. Meanwhile, the viscounties of Labourd and Soule under English suzerainty were finally annexed to France after the Hundred Years' War at the capitulation of Bayonne in 1451.

In Navarre, the civil wars between the Agramontese and the Beaumontese paved the way for the Spanish conquest of the bulk of Navarre from 1512 to 1521. The Navarrese territory north of the Pyrenees remaining out of Spanish rule would end up being formally absorbed to France in 1620. In the coming decades after the annexation, the Basque Country suffered attempts of religious, ideological and national homogenization, coming to a head in the 1609-1611 Basque witch trials at either side of the border of the kingdoms.

Nevertheless, the Basque provinces still enjoyed a great deal of self-government until the French Revolution in the Northern Basque Country, when the traditional provinces were reshaped to form the current Pyrénées-Atlantiques department along with Béarn. On the Southern Basque Country, the Charters were upheld up to the civil wars called Carlist Wars, when the Basques supported heir apparent Carlos and his descendants to the cry of "God, Fatherland, King" (Charters abolished definitely in 1876). The ensuing centralised status quo bred dissent and frustration in the region, giving rise to Basque nationalism by the end of the 19th century, influenced by European Romantic nationalism.

Since then, attempts were made to find a new framework for self-empowerment. The occasion seemed to have reached on the proclamation of the 2nd Spanish Republic in 1931, when a draft statute was drawn up for the Southern Basque Country (Statute of Estella), but was discarded in 1932. In 1936 a short-lived statute of autonomy was approved for the Gipuzkoa, Álava and Biscay provinces, while war foiled any progress. After Franco´s dictatorship, a new statute was designed that resulted in the creation of the current Basque Autonomous Community and Navarre, with a limited self-governing status, as settled by the Spanish Constitution. However, a significant part of Basque society is still attempting higher degrees of self-empowerment (see Basque nationalism), sometimes by acts of violence. The French Basque Country, meanwhile, lacks any political or administrative recognition whatsoever, while a large number of regional representatives have lobbied to create a Basque department, to no avail so far.

Demographics

The Basque Country has a population of approximately 3 million as of early 2006. The population density, at about 140/km² (360/sq. mile) is above the average of Spain or France, but the distribution of the population is fairly unequal and it is concentrated around the main cities. A third of the population is concentrated in the Greater Bilbao metropolitan area, whilst most of the interior of the French Basque Country and some areas of Navarre remain sparsely populated: density culminates at about 500/km² for Biscay but goes down at 20/km² in the northern inner provinces of Lower Navarre and Soule.[8]

A significant majority of the population of the Basque country live inside the Basque Autonomous Community (about 2,100,000, that is 70% of the population) while about 600,000 live in Navarre (20% of the population) and about 300,000 (roughly 10%) in Northern Basque Country.[9]

José Aranda Aznar writes[10] that 30% of the population in the Basque Country Autonomous Community were born in other regions of Spain and that 40% of the people living in that territory do not have a single Basque parent.

Most of these peoples of Galician and Castilian stock arrived in the Basque Autonomous Community in the late 19th century and throughout the 20th century, as the region became more and more industrialized and prosperous and additional workers were needed to support the economic growth. Descendants of immigrants from other parts of Spain have since been considered Basque for the most part, at least formally.[10]

Over the last 25 years, some 380,000 people have left the Basque Autonomous Community, of which some 230,000 have moved to other parts of Spain. While certainly many of them are people returning to their original homes when starting their retirement, there is also a sizeable tract of Basque natives in this group who have moved due to a Basque nationalist political environment (including ETA's killings) which they regard as overtly hostile.[11] These have been quoted to be as many as 10% of the population in the Basque Community.[12]

Biggest cities

- Bilbao 354,145 inhabitants (Basque Autonomous Community, BAC)

- Vitoria-Gasteiz 235,661 inhabitants (BAC)

- Pamplona 195,769 inhabitants (Navarre)

- Donostia-San Sebastián 183,308 inhabitants (BAC)

- Barakaldo 95,640 inhabitants (BAC)

- Getxo 82,327 inhabitants (BAC)

- Irun 60,261 inhabitants (BAC)

- Portugalete 49,118 inhabitants (BAC)

- Santurtzi 47,320 inhabitants (BAC)

- Bayonne 44,300 inhabitants (Pyrénées Atlantiques Department)

Non-Basque minorities in the Basque Country

Historical minorities

Various Romani groups existed in the Basque Country and some still exist as ethnic groups. These were grouped together under the generic terms ijituak (Egyptians) and buhameak (Bohemians) by Basque speakers.[citation needed]

- The (C)agots also were found north and south of the mountains. They lived as untouchables in Basque villages and were allowed to marry only among themselves. Their origin is unclear and has historically been surrounded with superstitions. Nowadays, they have mostly assimilated into the general society.

- The Cascarots were a Roma subgroup found mainly in the Northern Basque Country.

- A subgroup of Kalderash Roma resident in the Basque Country were the Erromintxela who are notable for speaking a rare mixed language. This is based on Basque grammar but using Romani-derived vocabulary.[13]

- The Mercheros were Quinqui-speakers, travelling as cattle merchants and artisans. Following the industrialization, they settled in slums near big cities.

In the Middle Ages, many so-called Franks of Occitan language settled along the Way of Saint James in Navarre and Guipuscoa but were eventually assimilated. Navarre also held Jewish and Muslim minorities but these were expelled or forced to assimilate after the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. One of the outstanding members of such minorities was Benjamin of Tudela.

Recent immigration

Since the 1980s, as a consequence of its considerable economic prosperity, the Basque Country has received an increasing number of immigrants, mostly from Eastern Europe, North Africa, Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and China. The vast majority of these immigrants have settled in the major urban areas.

Language

Currently, the predominant languages in the Spanish Basque Country and French Basque Country are, respectively, Spanish and French. In the historical process of forging themselves as nation-states, both Spanish and French governments have, at times, tried to suppress Basque linguistic identity.[14] The language chosen for public education is the most obvious expression of this phenomenon, something which surely had an effect in the current status of Basque.

Despite being spoken in a relatively small territory, the rugged features of the Basque countryside and the historically low population density[citation needed] resulted in Basque being a historically heavily dialectalised language, which increased the value of both Spanish and French, respectively, as lingua francas. In this regard, the current Batua standard of the Basque language was only introduced by the end of the 20th century, which helped Basque move away from being perceived – even by its own speakers – as a language unfit for educational purposes.[15]

While the French Republics –the epitome of the nation-state– have a long history of attempting the complete cultural absorption of ethnic minority groups —including the French Basques— Spain, in turn, has at most points in its history granted some degree of linguistic, cultural, and political autonomy to its Basques. Basques have been historically overrepresented both in the Spanish Marine and military ever since the times of the Spanish Empire until recently, same as Basque ports have been historically crucial to inland Spain. Until they became progressively undone starting with the Carlist Wars, these historical ties resulted in the generation of a local Basque bourgeoisie, clergy and military men, historically close to the Spanish Monarchy, especially in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. In all, there was a gradual absorption of Spanish language in the Basque-speaking areas of the Spanish Basque Country, a phenomenon initially restricted to the upper urban classes, but progressively reaching the lower ones as well. Notice that Western Biscay, most of Alava and southern Navarre have been Spanish-speaking (or Romance-speaking) for centuries.

But under the regime of Francisco Franco, its government tried to suppress the newly born Basque nationalism, as it had fought on the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War in Gipuzkoa and Biscay. In general, during these years, cultural activity in Basque was limited to folkloric issues and the Roman Catholic Church, while a higher, yet still limited degree of tolerance was granted to Basque culture and language in Álava and Navarre, since both areas mostly supported Francoist troops during the war.

Nowadays, the Basque Country within Spain enjoys an extensive cultural and political autonomy and Basque is an official language along with Spanish. In Spain, it is favoured by a set of language policies sponsored by the Basque regional government which aim at the generalization of its use. It is spoken by approximately a quarter of the total Basque Country, its stronghold being the contiguous area formed by Guipúzcoa, northern Navarre and the Pyrenean French valleys. It is not spoken natively in most of Álava, western Biscay and the southern half of Navarre. Of a total estimation of some 650,000 Basque speakers, approximately 550,000 live in the Spanish Basque country, the rest in the French.[16]

The Basque education system in Spain has three types of schools differentiated by their linguistic teaching models: A, B and D. Model D, with education entirely in Basque, and Spanish as a compulsory subject, is the most widely chosen model by parents. In Navarre there is an additional G model, with education entirely in Spanish.

In Navarre the ruling conservative government of Unión del Pueblo Navarro opposes Basque nationalist attempts to provide education in Basque through all Navarre (which would include areas where it is not traditionally spoken). Basque language teaching in the public education network is therefore limited to the Basque speaking north and central regions. In the central region, Basque teaching in the public education network is fairly limited, and part of the existing demand is served via private schools or ikastolak. Spanish is spoken by the entire population, with few exceptions in remote rural areas.

The situation of the Basque language in the French Basque Country is tenuous[vague], where monolingual public schooling in French exert great pressure on the Basque language. Basque teaching is mainly in private schools, or ikastolak.

Universities

The earliest university in the Basque Country was the University of Oñati, founded in 1540 in Hernani and moved to Oñati in 1548. It lasted in various forms until 1901.[17] In 1868, in order to fulfill the need for college graduates for the thriving industry that was flourishing in the Bilbao area, there was an unsuccessful effort to establish a Basque-Navarrese University. Nonetheless, in 1897 the Bilbao Superior Technical School of Engineering (the first modern faculty of engineering in Spain), was founded as a way of providing engineers for the local industry; this faculty is nowadays part of the University of the Basque Country. Almost at the same time, the urgent need for business graduates led to the establishment of the Commercial Faculty by the Jesuits, and, some time thereafter, the Jesuits expanded their university by formally founding the University of Deusto in Deusto (now a Bilbao neighbourhood) by the turn of the century, a private university where the Comercial Faculty was integrated. The first modern Basque public university was the Basque University, founded November 18, 1936 by the autonomous Basque government in Bilbao in the midst of the Spanish Civil War. It operated only briefly before the government's defeat by Francisco Franco's fascist forces.[18]

Several faculties, originally teaching only in Spanish, were founded in the Basque region in the Francisco Franco era. A public faculty of economics was founded in Sarriko (Bilbao) in the 1960s, and a public faculty of medicine was also founded during that decade, thus expanding the college graduate schools. However, all the public faculties in the Basque Country were organized as local branches of Spanish universities. For instance, the School of Engineering was treated as a part of the University of Valladolid, some 400 km away from Bilbao. Indeed, the lack of a central governing body for the public faculties of the Bilbao area, namely those of Economics in Sarriko, Medicine in Basurto, Engineering in Bilbao and the School of Mining in Barakaldo (est. 1910s), was seen as a gross handicap for the cultural and economic development of the area, and so, during the late 1960s many formal requests were made to the Francoist government in order to establish a Basque public university that would unite all the public faculties already founded in Bilbao. As a result of that, the University of Bilbao was founded in the early 1970s, which has now evolved into the University of the Basque Country with campuses in the western three provinces.

In Navarre, Opus Dei manages the University of Navarre with another campus in San Sebastián. Additionally, there is also the Public University of Navarre managed by the Navarrese Foral Government.

Mondragón Corporación Cooperativa has established its institutions for higher education as the Mondragon University, based in Mondragón and nearby towns.

There are numerous other significant Basque cultural institutions in the Basque Country and elsewhere. Most Basque organizations in the United States are affiliated with NABO (North American Basque Organizations, Inc.).

Politics

Parties with presence in all the Basque Country as considered in this article

- The Basque Nationalist Party (EAJ-PNV-PNB) is the oldest of all nationalist parties, with over 100 years of history. It is Christian-democrat and has evolved towards rather moderate positions though it still keeps the demand for self-determination and eventual independence. It is the main party in the Basque Autonomous Community (BAC) and is the most voted party (about 40% population), but its presence in Navarre and especially in the French Basque country is marginal.

- Eusko Alkartasuna (EA) (Basque Solidarity). A splinter from PNV since 1984, under the leadership of charismatic lehendakari Carlos Garaikoetxea,[19] as EAJ-PNV had pacted with the Spanish right in Navarre (against the opinion of the local federation) in exchange for support in Bilbao. They are defined as social-democrats and are quite more emphatic in their nationalist claims. Their presence in the French Basque Country is marginal, if any.

- Batasuna (Unity) was formerly known as Herri Batasuna (People's Union) and Euskal Herritarrok (We Basque Citizens). Its ideology is radical nationalist and socialist. It was declared illegal in 2003 after the Spanish parliament passed a new Law of Political Parties, due to its relation[20] with the terrorist organization ETA. It formerly had representation in the Southern Basque Country, including Navarre, where it is the main Basque independentist force, despite being now forbidden to run in the elections: the last year they were able to participate in elections of Navarre was 1999, getting 15.58% of the votes, while the second nationalist party, EA/EAJ-PNV got just 5.44%.[citation needed] Its presence in the French Basque Country is marginal.

Parties with presence only in the French Basque Country

- French Socialist Party, social-democrat, France-wide.

- Union for a Popular Movement, conservative, France-wide.

- Abertzaleen Batasuna (Patriots' Union), the radical left wing Basque nationalist force of the North (allied with Aralar).

- Euskal Herria Bai (EH Bai), a coalition party formed by Abertzaleen Batasuna, Batasuna and Eusko Alkartasuna.

Parties with presence in all of the Spanish Basque Country

- Spanish Socialist Worker Party (PSOE), social-democrat, with its branches:

- PSE-EE (Mixed Spanish and Basque acronym for: Socialist Party of the Basque Country - Basque Country's Left) in the Basque Autonomous Community (BAC)

- PSN (Socialist Party of Navarre) in Navarre

- People's Party (PP), conservative, with its branches:

- Partido Popular de Navarra (People's Party of Navarre) in Navarre

- Partido Popular del País Vasco (People's Party of The Basque Country) in the BAC

- United Left (IU), left-wing around the former Communist Party, federalist and republican, with its branches:

- Ezker Batua (United Left) (EB-IU) in the BAC

- Izquierda Unida de Navarra (United Left of Navarre) (IUN) in Navarre

- Aralar Party: a breakaway faction separated from Batasuna, stronger in Navarre. Independentist and left-leaning, rejects the use of violence (allied with Abertzaleen Batasuna).

Parties with presence only in Navarre

- Navarrese People's Union, formerly attached to People's Party. It has been the ruling party in Navarre since 1996, and is a firm opponent of Basque nationalism and the idea of a greater Basque Country. They stress the singularities and own history of Navarre instead.

- Batzarre (Assembly), left-wing coalition around neo-communist Zutik (Stand), mostly internationalist but favorable to self-determination.

- Eusko Alkartasuna, Aralar, Batzarre and EAJ-PNV run together to the latest Navarrese elections under the name Nafarroa Bai (Navarre Yes)

Basque Nationalism

Political status and violence

Since the 19th century, Basque nationalism (abertzaleak) has demanded the right of some kind of self-determination[citation needed], which is supported by 60% of Basques in the Basque Autonomous Community, and independence, which would be supported in this same territory, according to a poll, by approximately 25%[21] of them, the 5% decrease from the previous poll suggesting that the desire for independence is steadily decreasing. This desire for independence is particularly stressed among leftist Basque nationalists. The right of self-determination was asserted by the Basque Parliament in 1990, 2002 and 2006.[22] Since[citation needed] self-determination is not recognized in the Spanish Constitution of 1978, some Basques abstained and some even voted against it in the referendum of December 6 of that year. However, it was approved by a clear majority at the Spanish level, and simple majority at Navarrese and Basque levels. The derived autonomous regimes for the BAC was approved in later referendum but the autonomy of Navarre (amejoramiento del fuero: "improvement of the charter") was never subject to referendum but just approved by the Navarrese Cortes (parliament). There are not many sources on the issue for the French Basque country.

ETA

Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) is recognized as a terrorist organization by the European Union and the United States. In 2006, ETA declared a "permanent ceasefire" after nearly 40 years fighting for independence from Spanish and French authorities and the annexation of all Basque lands to a united, socialist state. In June 2007, ETA officially ended the "permanent ceasefire". Since then it has committed several bomb attacks and assassinations. In September 2010 ETA again announced a permanent cessation of violence.[23]

Sports

The Basque Country has also contributed some sportsmen, primarily in football, cycling, jai-alai, rugby union and surfing.

The main sport in the Basque Country, as in the rest of Spain and much of France, is football. The top teams Athletic Bilbao, Real Sociedad, Osasuna, Eibar, Alavés, Real Unión and Barakaldo play in the Spanish national league. Athletic Bilbao has a policy of hiring only Basque players. This policy has been applied with variable flexibility. Real Sociedad used to practice the same policy, until they signed Irish striker John Aldridge in the late 80's.

Football is not that popular in the north but the region has produced two very well known and successful football players, Bixente Lizarazu and Didier Deschamps.

Cycling as a sport is very popular in the Basque Country. Cycling races often see Basque fans lining the roads wearing orange, the corporate color of the telco Euskaltel, coining the term the orange crush during the Pyrenees stages of the Tour de France. Miguel Indurain was born in Atarrabia (Navarre), and he won 5 French Tours.

Fellow Basque cyclist Abraham Olano has won the Vuelta a España and the World Championship.

Two professional, UCI ProTeam cycling teams hail from the Basque Country You have called {{Contentious topics}}. You probably meant to call one of these templates instead:

Alerting users

- {{alert/first}} ({{Contentious topics/alert/first}}) is used, on a user's talk page, to "alert", or draw a user's attention, to the contentious topics system if they have never received such an alert before. In this case, this template must be used for the notification.

- {{alert}} ({{Contentious topics/alert}}) is used, on a user's talk page, to "alert", or draw a user's attention, to the fact that a specific topic is a contentious topic. It may only be used if the user has previously received any contentious topic alert, and it can be replaced by a custom message that conveys the contentious topic designation.

- {{alert/DS}} ({{Contentious topics/alert/DS}}) is used to inform editors that the old "discretionary sanctions" system has been replaced by the contentious topics system, and that a specific topic is a contentious topic.

- {{Contentious topics/aware}} is used to register oneself as already aware that a specific topic is a contentious topic.

Editnotices

- {{Contentious topics/editnotice}} is used to inform editors that a page is covered by the contentious topics system using an editnotice. Use the one below if the page has restrictions placed on the page.

- {{Contentious topics/page restriction editnotice}} is used to inform editors that the page they are editing is subject to contentious topics restrictions using an editnotice. Use the above if there are no restrictions placed on the page.

Talk page notices

- {{Contentious topics/talk notice}} is used to provide additional communication, using a talk page messagebox (tmbox), to editors that they are editing a page that is covered by the contentious topics system. The template standardises the format and wording of such notices. Use the below if there are restrictions placed on the page.

- {{Contentious topics/page restriction talk notice}} is used to inform editors that page restrictions are active on the page using a talk page messagebox (tmbox). Use the above if there are no restrictions placed on the page.

- If a user who has been alerted goes on to disruptively edit the affected topic area, they can be reported to the arbitration enforcement (AE) noticeboard, where an administrator will investigate their conduct and issue a sanction if appropriate. {{AE sanction}} is used by administrators to inform a user that they have been sanctioned.

Miscellaneous

- {{Contentious topics/list}} and {{Contentious topics/table}} show which topics are currently designated as contentious topics. They are used by a number of templates and pages on Wikipedia. and You have called

{{Contentious topics}}. You probably meant to call one of these templates instead:

Alerting users

- {{alert/first}} ({{Contentious topics/alert/first}}) is used, on a user's talk page, to "alert", or draw a user's attention, to the contentious topics system if they have never received such an alert before. In this case, this template must be used for the notification.

- {{alert}} ({{Contentious topics/alert}}) is used, on a user's talk page, to "alert", or draw a user's attention, to the fact that a specific topic is a contentious topic. It may only be used if the user has previously received any contentious topic alert, and it can be replaced by a custom message that conveys the contentious topic designation.

- {{alert/DS}} ({{Contentious topics/alert/DS}}) is used to inform editors that the old "discretionary sanctions" system has been replaced by the contentious topics system, and that a specific topic is a contentious topic.

- {{Contentious topics/aware}} is used to register oneself as already aware that a specific topic is a contentious topic.

Editnotices

- {{Contentious topics/editnotice}} is used to inform editors that a page is covered by the contentious topics system using an editnotice. Use the one below if the page has restrictions placed on the page.

- {{Contentious topics/page restriction editnotice}} is used to inform editors that the page they are editing is subject to contentious topics restrictions using an editnotice. Use the above if there are no restrictions placed on the page.

Talk page notices

- {{Contentious topics/talk notice}} is used to provide additional communication, using a talk page messagebox (tmbox), to editors that they are editing a page that is covered by the contentious topics system. The template standardises the format and wording of such notices. Use the below if there are restrictions placed on the page.

- {{Contentious topics/page restriction talk notice}} is used to inform editors that page restrictions are active on the page using a talk page messagebox (tmbox). Use the above if there are no restrictions placed on the page.

- If a user who has been alerted goes on to disruptively edit the affected topic area, they can be reported to the arbitration enforcement (AE) noticeboard, where an administrator will investigate their conduct and issue a sanction if appropriate. {{AE sanction}} is used by administrators to inform a user that they have been sanctioned.

Miscellaneous

- {{Contentious topics/list}} and {{Contentious topics/table}} show which topics are currently designated as contentious topics. They are used by a number of templates and pages on Wikipedia..[24] The Caisse d'Epargne cycling team traces its history back to the Banesto team that included Indurain. The Euskaltel-Euskadi cycling team is commercially sponsored, but also works as an unofficial Basque national team and is partly funded by the Basque Government. Its riders are either Basque, or at least have grown up in the Basque cycling culture, present and former members of the team have been strong contenders in the Tour de France held annually in July and Vuelta a España held in September. Team leaders have included riders such as Iban Mayo, Haimar Zubeldia and David Etxebarria.

In the north, rugby union is another popular sport with the Basque community. In Biarritz, the local club is Biarritz Olympique Pays Basque, the name referencing the club's Basque heritage. They wear red, white and green, and supporters wave the Basque flag in the stands. They also recognize 16 other clubs as "Basque-friendly". A number of 'home' matches played by Biarritz Olympique in the Heineken Cup have taken place at Estadio Anoeta in San Sebastian.

The most famous Biarritz & Basque player is the legendary French fullback Serge Blanco, whose mother was Basque. Michel Celaya captained both Biarritz and France. French number 8 Imanol Harinordoquy is also a Biarritz & Basque player. Aviron Bayonnais is another top-flight rugby union club with Basque ties.

Before the banning of rugby league in 1940, a Basque club was the last to celebrate winning the cup.

Pelota (jai alai) is the Basque version of the European game family that includes real tennis and squash. Basque players, playing for either the Spanish or the French teams, dominate international competitions.

Mountaineering is popular due to the mountainous terrain of the Basque Country and its proximity to the Pyrenees. Alberto Iñurrategi Iriarte (Aretxabaleta, 1968) is one of the most respected mountaineers in the world. The Basque mountaineer has managed to crown the 14 eight thousands in the world, all of them "Alpine" style, i.e. without oxygen and few camps and without Sherpas. This is something only 8 people on the planet have achieved. Juanito Oiarzabal (from Vitoria) holds the world record for number of climbs above 8,000 meters, with 21. There are also great sport climbers in the Basque Country, such as, Josune Bereziartu, the only female to have climbed the grade 9a/5.14d; and Iker Pou, one of the most versatile climbers in the world. Patxi Usobiaga, proclaimed world champion in Xining, China, 2009. Edurne Pasaban is already the first woman climbing the fourteen eight-thousanders.

One of the top basketball clubs in Europe, Caja Laboral, is located in Vitoria-Gasteiz.

In recent years surfing has taken off on the Basque shores, and Mundaka and Biarritz have become spots on the world surf circuit.

Traditional Basque sports

See also

- Basque Country (autonomous community)

- Northern Basque Country, in France

- Basque people

- Basque cuisine

- Basque mythology

- List of active autonomist and secessionist movements

- Nationalities in Spain

- List of Basques

- Navarre

References

- ^ a b Area figures for Spanish Autonomous Communities have been found on the Instituto Geográfico Nacional website "Instituto Geográfico Nacional". Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- ^ For instance, as concerns Treviño, Eugène Goyheneche writes that it is "and integral part of Álava, administratively belonging to the province of Burgos" Le Pays Basque. Pau: SNERD. 1979., p. 25.

- ^ This figure has been obtained by addition of the area of the municipalities of Condado de Treviño (261 km²) and La Puebla de Arganzón (19 km²), as read on the website of the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spain) "Population, area and density by municipalties". Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- ^ UPN recuerda a Chivite que dejó muy claro que la Transitoria Cuarta no tenía sentido

- ^ See for instance HAIZEA, ed. (1999). Nosostros Los Vascos - Ama Lur - Gegrafia fisica y humana de Euskalherria (in Spanish). Lur. ISBN 84-7099-415-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coeditor=ignored (help), F J Gomez Piñeiro; et al. (eds.). Pays Basque La terre les hommes Labourd, Basse-Navarre, Soule (in French). San Sebastián: Elkar. ISBN 84-7407-091-0.{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help) or the statistical data of the Euskal Herria Databank "The Euskal Herria Databank". Gaindegia Association. Retrieved 14 September 2009. for sources including Esquiule, and Alexander Ugalde Zubirri. Euskal Herria - Un pueblo (in Spanish). Bilbao: Sua Edizioak. ISBN 84-8216-083-4.{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) or E. Asumendi; et al., eds. (2004). Munduko Atlasa (in Basque). Elkar. ISBN 84-9783-1284.{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help) for sources excluding Esquiule. - ^ This result is obtained by addition of the communal areas given by the Institut Géographique National ; we used for this addition the provincial subtotals as computed by "The Euskal Herria Databank". Gaindegia Association. Retrieved 14 September 2009..

- ^ Jean Goyhenetche (1993). Les Basques et leur histoire : mythes et réalités. Baiona, Donostia: Elkar. ISBN 2-903421-34-X.

- ^ A very readable map of population density for each municipality can be consulted online on the website muturzikin.com

- ^ See these sources for population statistics: Datutalaia and INE.

- ^ a b "La mezcla del pueblo vasco", Empiria: Revista de metodología de ciencias sociales, ISSN 1139-5737, Nº 1, 1998, pags. 121-180.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Spanish devolution

- ^ Erromintxela: Notas para una investigación sociolingüística, Oscar Vizarraga.

- ^ Torrealdi, J.M. El Libro Negro del Euskera (1998) Ttarttalo ISBN 84-8091-395-9

- ^ " El vascuence subvenía perfectamente a las necesidades de pequeñas comunidades agrícolas o de pescadores, a la vida religiosa y política de un mundo bastante aislado y de dimensionas pequeñas..." Pinillos, Jose Luis Coloquio sobre el problema del bilingüismo en el País Vasco Bilbao 1983

- ^ Basque language - English Pen

- ^ http://www.ehu.es/ingles/paginas/prin_i.htm http://www.ehu.es

- ^ http://basque.unr.edu/09/9.3/9.3.35t/9.3.35.07.univ.htm http://basque.unr.edu

- ^ Ilkka Nordberg. Regionalism and revenue. The moderate Basque Nationalist Party, PNV, 1980–1998. Doctoral dissertation: Department of History, University of Helsinki, 2005

- ^ Las caras de Batasuna. http://www.elmundo.es/eta/entorno/batasuna.html

- ^ http://www.elpais.com/articulo/espana/Solo/25/vascos/apoya/independencia/sondeo/Gobierno/Vitoria/elpporesp/20021225elpepunac_1/Tes elpais.com

- ^ EITB: Basque parliament adopts resolution on self-determination

- ^ ETA announce ceasefire, Sept 2010

- ^ "2009 Riders and teams Database - Cyclingnews.com". Retrieved 2009-08-14.