Gilgit: Difference between revisions

m Bot: link syntax/spacing and minor changes |

Shail kalp (talk | contribs) →1800s: USELESS aman malik was defeated and routed from gilgit and chitral became a tribuary of Jammu and Kashmir. |

||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

The area had been a flourishing tract but prosperity was destroyed by warfare over the next fifty years, and by the great flood of 1841 in which the river [[Indus]] was blocked by a landslip below the Hatu Pir and the valley was turned into a lake.<ref name="IGI">[http://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/gazetteer/pager.html?objectid=DS405.1.I34_V12_244.gif Gilgit - Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 12, p. 238]</ref> After the death of Abas, [[Sulaiman Shah]], raja of [[Yasin Valley|Yasin]], conquered Gilgit. Then, Azad Khan, raja of [[Punial]], killed Sulaiman Shah, taking Gilgit; then Tair Shah, raja of Buroshall ([[Nagar Valley|Nagar]]), took Gilgit and killed Azad Khan. Tair Shah's son Shah Sakandar inherited, only to be killed by Gaur Rahman, raja of Yasin of the [[Khushwakhte Dynasty]], when he took Gilgit. Then in 1842, Shah Sakandar's brother, [[Karim Khan]], expelled Gaur Rahman with the support of a [[Sikh Confederacy|Sikh]] army from Kashmir. The Sikh general, Nathu Shah, left garrison troops and Karim Khan ruled until Gilgit was ceded to [[Gulab Singh of Jammu and Kashmir]] in 1846 by the [[Treaty of Amritsar]],<ref name="Drew"/> and [[Dogra]] troops replaced the [[Sikh]] in Gilgit. |

The area had been a flourishing tract but prosperity was destroyed by warfare over the next fifty years, and by the great flood of 1841 in which the river [[Indus]] was blocked by a landslip below the Hatu Pir and the valley was turned into a lake.<ref name="IGI">[http://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/gazetteer/pager.html?objectid=DS405.1.I34_V12_244.gif Gilgit - Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 12, p. 238]</ref> After the death of Abas, [[Sulaiman Shah]], raja of [[Yasin Valley|Yasin]], conquered Gilgit. Then, Azad Khan, raja of [[Punial]], killed Sulaiman Shah, taking Gilgit; then Tair Shah, raja of Buroshall ([[Nagar Valley|Nagar]]), took Gilgit and killed Azad Khan. Tair Shah's son Shah Sakandar inherited, only to be killed by Gaur Rahman, raja of Yasin of the [[Khushwakhte Dynasty]], when he took Gilgit. Then in 1842, Shah Sakandar's brother, [[Karim Khan]], expelled Gaur Rahman with the support of a [[Sikh Confederacy|Sikh]] army from Kashmir. The Sikh general, Nathu Shah, left garrison troops and Karim Khan ruled until Gilgit was ceded to [[Gulab Singh of Jammu and Kashmir]] in 1846 by the [[Treaty of Amritsar]],<ref name="Drew"/> and [[Dogra]] troops replaced the [[Sikh]] in Gilgit. |

||

Nathu Shah and Karim Khan both transferred their allegiance to Gulab Singh, continuing local administration. When [[Hunza (princely state)|Hunza]] attacked in 1848, both of them were killed. Gilgit fell to the Hunza and their Yasin and Punial allies, but was soon reconquered by Gulab Singh's Dogra troops. With the support of Gaur Rahman, Gilgit's inhabitants drove their new rulers out in an uprising in 1852. Gaur Rahman then ruled Gilgit until his death in 1860, just before new Dogra forces from [[Ranbir Singh]], son of Gulab Singh, captured the fort and town.<ref name="Drew"/> |

Nathu Shah and Karim Khan both transferred their allegiance to Gulab Singh, continuing local administration. When [[Hunza (princely state)|Hunza]] attacked in 1848, both of them were killed. Gilgit fell to the Hunza and their Yasin and Punial allies, but was soon reconquered by Gulab Singh's Dogra troops. With the support of Gaur Rahman, Gilgit's inhabitants drove their new rulers out in an uprising in 1852. Gaur Rahman then ruled Gilgit until his death in 1860, just before new Dogra forces from [[Ranbir Singh]], son of Gulab Singh, captured the fort and town.<ref name="Drew"/>. In 1870s Chitral was threatened by Afghans Maharaja Ranbir Singh was firm in protecting Chitral from Afghans the Mehtar of Chitral ask for help, In 1876 Chitral accepted the authority of Jammu Clan and in reverse get the protection from the Dogras who have in the past took part in many victories over Afghans during the time of Gulab Singh Dogra.<ref>http://books.google.co.in/books?id=_U55rXIijnsC&pg=PA167&dq=maharaja+ranbir+singh+chitral&hl=en&ei=aiB3TubAB43orQfb0Ni_Aw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CEEQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=maharaja%20ranbir%20singh%20chitral&f=false</ref> |

||

===British era=== |

===British era=== |

||

Revision as of 11:02, 19 September 2011

Gilgit | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

| Country | |

| Region | Gilgit-Baltistan |

| Division | Gilgit Division |

| District | Gilgit District |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Faqeer Muhammad |

| Elevation | 1,500 m (4,900 ft) |

| Population (1998) | 216,760[citation needed] |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PST) |

| Postal code | 15100 |

| Area code | +92 5811 |

Gilgit (Urdu/Burushaski: گلگت, Hindi: गिलगित) is the capital city of Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. Gilgit City forms a tehsil of Gilgit, within Gilgit District. Its ancient name was Sargin, later to be known as Gilit, and it is still called Gilit or Sargin-Gilit by local people. In the Burushaski language, it is named Geelt and in Wakhi and Khowar it is called Gilt. Ghallata is considered its name in ancient Sanskrit literature. Gilgit City is one of the two major hubs in the Northern Areas for mountaineering expeditions to the Karakoram and other the peaks in the Himalayas, the other hub being Skardu.[citation needed]

History

Gilgit was an important city on the Silk Road, along which Buddhism was spread from South Asia to the rest of Asia.[citation needed]

The Dards and Chinas appear in many of the old Pauranic lists of peoples who lived in the region, with the former also mentioned in Ptolemy's accounts of the region. Two famous travellers, Faxian and Xuanzang, traversed Gilgit according to their accounts.[citation needed]

Early history

The former rulers had the title of Ra, and there is reason to suppose that they were at one time Hindus, but for the last five centuries and a half they have been Mohammedans. The names of the Hindu Ras have been lost, with the exception of the last of their number, Shri Buddutt. Tradition relates that he was killed by a Mohammedan adventurer, who married his daughter and founded a new dynasty, since called Trakhàn, from a celebrated Ra named Trakhan, who reigned about the commencement of the fourteenth century. The previous rulers—of whom Shri Buddutt was the last—were called Shahreis.[1]

Trakhàn Dynasty

Gilgit was ruled for centuries by the local Trakhàn Dynasty, which ended about 1810 with the death of Raja Abas, the last Trakhàn Raja.[2]

The rulers of Hunza and Nager also claim origin with the Trakhàn dynasty. They claim descent from a heroic Kayani Prince of Persia, Azur Jamshid (also known as Shamsher), who secretly married the daughter of the king Shri Badat. She conspired with him to overthrow her cannibal father.[3] Sri Badat's faith is theorised as Hindu by some[3][4] and Buddhist by others.[5][6] However, considering the region's Buddhist heritage, with the most recent influence being Islam, the most likely preceding influence of the region is Buddhism. Though the titular Sri and the name Badat denotes a Hindu origin of this ruler.

Prince Azur Jamshid succeeded in overthrowing King Badat who was known as Adam Khor (literally man-eater),[7][8] often demanding a child a day from his subjects, his demise is still celebrated to this very day by locals in traditional annual celebrations.[9] In the beginning of the new year, where a Juniper procession walks along the river, in memory of chasing the cannibal king Sri Badat away.[10]

Azur Jamshid abdicated after 16 years of rule in favour of his wife Nur Bakht Khatùn until their son and heir Garg, grew of age and assumed the title of Raja and ruled, for 55 years. The dynasty flourished under the name of the Kayani dynasty until 1421 when Raja Torra Khan assumed rulership. He ruled as a memorable king until 1475. He distinguished his family line from his step brother Shah Rais Khan (who fled to the king of Badakshan and with who's help he gained Chitral from Raja Torra Khan), as the now-known dynastic name of Trakhàn. The descendants of Shah Rais Khan were known as the Ra'issiya Dynasty.[11]

1800s

The period of greatest prosperity was probably under the Shin Ras, whose rule seems to have been peaceable and settled. The whole population, from the Ra to the poorest subject lived by agriculture. According to tradition, Shri Buddutt's rule extended over Chitral, Yassin, Tangir, Darel, Chilas, Gor, Astor, Hunza, Nagar and Haramosh all of which were held by tributary princes of the same family.[12]

The area had been a flourishing tract but prosperity was destroyed by warfare over the next fifty years, and by the great flood of 1841 in which the river Indus was blocked by a landslip below the Hatu Pir and the valley was turned into a lake.[13] After the death of Abas, Sulaiman Shah, raja of Yasin, conquered Gilgit. Then, Azad Khan, raja of Punial, killed Sulaiman Shah, taking Gilgit; then Tair Shah, raja of Buroshall (Nagar), took Gilgit and killed Azad Khan. Tair Shah's son Shah Sakandar inherited, only to be killed by Gaur Rahman, raja of Yasin of the Khushwakhte Dynasty, when he took Gilgit. Then in 1842, Shah Sakandar's brother, Karim Khan, expelled Gaur Rahman with the support of a Sikh army from Kashmir. The Sikh general, Nathu Shah, left garrison troops and Karim Khan ruled until Gilgit was ceded to Gulab Singh of Jammu and Kashmir in 1846 by the Treaty of Amritsar,[2] and Dogra troops replaced the Sikh in Gilgit.

Nathu Shah and Karim Khan both transferred their allegiance to Gulab Singh, continuing local administration. When Hunza attacked in 1848, both of them were killed. Gilgit fell to the Hunza and their Yasin and Punial allies, but was soon reconquered by Gulab Singh's Dogra troops. With the support of Gaur Rahman, Gilgit's inhabitants drove their new rulers out in an uprising in 1852. Gaur Rahman then ruled Gilgit until his death in 1860, just before new Dogra forces from Ranbir Singh, son of Gulab Singh, captured the fort and town.[2]. In 1870s Chitral was threatened by Afghans Maharaja Ranbir Singh was firm in protecting Chitral from Afghans the Mehtar of Chitral ask for help, In 1876 Chitral accepted the authority of Jammu Clan and in reverse get the protection from the Dogras who have in the past took part in many victories over Afghans during the time of Gulab Singh Dogra.[14]

British era

In 1877, in order to guard against the advance of Russia, the British Government, acting as the suzerain power of Kashmir, established the Gilgit Agency. The Agency was re-established under control of the British Resident in Jammu and Kashmir. It comprised the Gilgit Wazarat; the State of Hunza and Nagar; the Punial Jagir; the Governorships of Yasin, Kuh-Ghizr and Ishkoman, and Chilas.

The Tajiks of Xinjiang sometimes enslaved the Gilgiti and Kunjuti Hunza.[15]

Many Gilgiti and Kunjuti Hunza were also enslaved in China After being freed due to the efforts of British authorities in China, many slaves such as Gilgitis in Xinjiang cities like Tashkurgan, Yarkand, and Karghallik, stayed rather than return Hunza in Gilgit. Most of these slaves were women who married local slave and non slave men and had children with them. Sometimes the women were married to their masters, other slaves, or free men who were not their masters. There were ten slave men to slave women married couples, and 15 master slave women couples, with several other non master free men married to slave women. Both slave and free Turki and Chinese men fathered children with Hunza slave women. A free man, Khas Muhammad, was married with 2 children to a woman slave named Daulat, aged 24. A Gilgiti slave woman aged 26, Makhmal, was married to a Chinese slave man, Allah Vardi and had 3 children with him.[16]

In 1935, the British demanded Jammu and Kashmir to lease them Gilgit town plus most of the Gilgit Agency and the hill-states Hunza, Nagar, Yasin and Ishkoman for 60 years. Maharaja Hari Singh had no choice but to acquiesce. The leased region was then treated as part of British India, administered by a Political Agent at Gilgit responsible to Delhi, first through the Resident in Jammu and Kashmir and later a British Agent in Peshawar.[citation needed]

Jammu and Kashmir State no longer kept troops in Gilgit and a mercenary force, the Gilgit Scouts, was recruited with British officers and paid for by Delhi. In April 1947, Delhi decided to formally retrocede the leased areas to Hari Singh’s Jammu and Kashmir State as of August 15, 1947. The transfer was to formally take place on August 1.[citation needed]

1900s

Gilgit Scouts progressed with Pakistani troops from north through High Himalayas and contributed in attacking of Skardu in summer 1948, pushing further towards Ladakh area.[citation needed]

After Pakistani advances of early 1948, Indian troops gathered momentum in late 1948. Finally, the newly formed India asked UN intervention, and a ceasefire was agreed on December 31, 1948. This conflict left Pakistan with roughly two-fifths of Kashmir along with Gilgit and Baltistan, leaving three-fifths of Kashmir along with Jammu and Leh to India.[citation needed]

Climate

Gilgit experiences a desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh). Weather conditions for Gilgit are dominated by its geographical location, a valley in a mountainous area, southwest of Karakoram range. The prevalent season of Gilgit is winter, occupying the valley eight to nine months a year.

Gilgit lacks significant rainfall, averaging in 120 to 240 millimetres (4.7 to 9.4 in) annually, as monsoon breaks against the southern range of Himalayas. Irrigation for land cultivation is obtained from the rivers, abundant with melting snow water from higher altitudes.

The summer season is brief and hot. The piercing sunrays may raise the temperature up to 40 °C (104 °F), yet it is always cool in the shade. As a result of this extremity in the weather, landslides and avalanches are frequent in the area.[17]

| Climate data for Gilgit | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.3 (48.7) |

12.0 (53.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

28.4 (83.1) |

34.3 (93.7) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.3 (95.5) |

31.6 (88.9) |

25.3 (77.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

11.0 (51.8) |

23.6 (74.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.7 (27.1) |

2.5 (36.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.7 (53.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.1 (64.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

6.6 (43.9) |

.6 (33.1) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 4.0 (0.16) |

6.0 (0.24) |

12.6 (0.50) |

23.0 (0.91) |

25.3 (1.00) |

6.1 (0.24) |

15.6 (0.61) |

15.5 (0.61) |

6.5 (0.26) |

8.4 (0.33) |

1.8 (0.07) |

4.1 (0.16) |

128.9 (5.07) |

| Source: [18] | |||||||||||||

Gilgit manuscripts

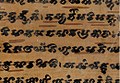

The Gilgit manuscripts[19] were nominated[20] in 2006 to be included on the UNESCO Memory of the World register, but without success. The Gilgit manuscripts are among the oldest manuscripts in the world, and the oldest manuscript collection surviving in Pakistan and India,[19][21] having major significance in the areas of Buddhist studies and the evolution of Asian and Sanskrit literature. The manuscripts are believed to have been written in the 5th to 6th Century AD, though some more manuscripts were discovered in the succeeding centuries, which were also classified as Gilgit manuscripts.

This corpus of manuscripts was discovered in 1931 in Gilgit, containing many Buddhist texts such as four sutras from the Buddhist canon, including the famous Lotus Sutra. The manuscripts were written on birch bark in the Buddhist form of Sanskrit in the Sharada script. The Gilgit manuscripts cover a wide range of themes such as iconometry, folk tales, philosophy, medicine and several related areas of life and general knowledge.

Tourism and transport

Gilgit city is one of the two major hubs for all mountaineering expeditions in Gilgit-Baltistan. Almost all tourists headed for treks in Karakoram or Himalaya Ranges arrive at Gilgit first. Many tourists choose to travel to Gilgit by air, since the road travel between Islamabad and Gilgit, by the Karakoram Highway, takes nearly 14–24 hours, whereas the air travel takes a mere 45–50 minutes.[citation needed]

Places to visit

There are several tourist attractions relatively close to Gilgit: Naltar Valley with Naltar Peak, Hunza Valley, Nagar Valley, Ferry Meadows in Raikot, Shigar town, Skardu city, Haramosh Peak in Karakoram Range, Bagrot-Haramosh Valley, Deosai National Park, Astore Valley, Rama Lake, Juglot town, Phunder village, Yasin Valley and Kargah Valley.

Road transport

Gilgit lies about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) off the Karakoram Highway (KKH). The KKH connects it to Chilas, Dasu, Besham, Mansehra, Abbottabad and Islamabad in the south. In the North it is connected to Karimabad (Hunza) and Sust in the Northern Areas and to the Chinese cities of Tashkurgan, Upal and Kashgar in Xinjiang.

There are various transports companies i.e. Silk Route Transport Pvt, Masherbrum Transport Pvt and Northern Areas Transport Corporation (NATCO), from these NATCO offers most coverage. It offers passenger road service between Islamabad, Gilgit, Sust and Tashkurgan, and road service between Kashgar and Gilgit (via Tashkurgan and Sust) started in the summer of 2006. However, the border crossing between China and Pakistan at Khunjerab Pass—the highest border of the world—is open only between May 1 and October 15 of every year. During winter, the roads are blocked by snow. Even during the monsoon season in summer, the roads are often blocked due to landslides. The best time to travel on Karakoram Highway is spring or early summer.[citation needed]

Health care

Tuberculosis, endocrinal disorders with mainly iodine deficiency disorders, iron deficiency, and diarrheal diseases are more common. Sewage system has yet to be fully established, electricity and water supply are still faulty. These factors make a hindrance in developing a strong health care system.[citation needed]

Sister cities

Gallery

-

Danyor Tunnel Gilgit

-

Danyor Tunnel

-

Danyor Bridge Gilgit

-

Manuscript of the Buddhist Jyotiṣkāvadāna text written in the early Sharada script, from Gilgit.

See also

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

- Astore

- Hunza

- Skardu

- Karakoram

- Northern Areas

- National Highways of Pakistan

- Xinjiang

- Karakoram Highway

- Kashghar

- Kashmir

- Parri Bangla

- Shina language

- Shin of Hindukush

- Nagar (princely state)

References

- ^ Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh by John Bidduph published by Sang-e-Meel -Publications Page 20

- ^ a b c Drew, Frederic (1875) The Jummoo and Kashmir Territories: A Geographical Account E. Stanford, London, OCLC 1581591, republished a number of times

- ^ a b The Gilgit Agency, 1877-1935 by Amar Singh Chohan, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors 1984, p4

- ^ Between the Oxus and the Indus by Reginald Charles Francis Schomberg, 1976, p249

- ^ Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5: Proceedings of the Fourth and Fifth by Henry Osmaston, Philip Denwood, 1995 Motilal Banarsidas, p226

- ^ History of Northern Areas of Pakistan by Ahmad Hasan Dani, 1989, p163

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India. Provincial Series: Kashmir and Jammu, ISBN 0543917762, Adamant, p107

- ^ Between the Oxus and the Indus by Reginald Charles Francis Schomberg, 1976, p144

- ^ Dissertation page 21

- ^ Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5 by Henry Osmaston, Philip Denwood, Motilal Banarsidass Publ. 1995, p229

- ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia By Ahmad Hasan Dani, Vadim Mikhaĭlovich, Motilal Banarsidass Publ 1999, p216-217

- ^ Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh by John Bidduph published by Sang-e-Meel -Publications Page 20 and 21

- ^ Gilgit - Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 12, p. 238

- ^ http://books.google.co.in/books?id=_U55rXIijnsC&pg=PA167&dq=maharaja+ranbir+singh+chitral&hl=en&ei=aiB3TubAB43orQfb0Ni_Aw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CEEQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=maharaja%20ranbir%20singh%20chitral&f=false

- ^ Sir Thomas Douglas Forsyth (1875). Report of a mission to Yarkund in 1873, under command of Sir T. D. Forsyth: with historical and geographical information regarding the possessions of the ameer of Yarkund. Printed at the Foreign department press. p. 56. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- ^ Raṇabīra Samāddāra (2002). Space, territory, and the state: new readings in international politics. Orient Blackswan. p. 83. ISBN 8125022090. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- ^ Alam Zaib. "Somethings about Gilgit". Karachi, Pakistan. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ "Gilgit weather averages". World Meteorological Association. June 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Gyan Marwah. "Gilgit Manuscript - Piecing Together Fragments of History". The South Asian Magazine. Haryana, India. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ "Gilgit Manuscript". Memory of the World Register. UNESCO. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ Dutt, Nalinaksha (1939). Gilgit Manuscripts. Vol. I. Calcutta, India: Calcutta Oriental Press Ltd. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Further reading

- The Gilgit Game by John Keay (1985) ISBN 0-19-577466-3

- Drew, Frederic. Date unknown. The Northern Barrier of India: a popular account of the Jammoo and Kashmir Territories with Illustrations. Reprint: Light & Life Publishers, Jammu. 1971.

- Jettmar, Karl, 1980. Bolor & Dardistan. National Institute of Folk Heritage, Islamabad.

- Knight, E. F. 1893. Where Three Empires Meet: A Narrative of Recent Travel in: Kashmir, Western Tibet, Gilgit, and the adjoining countries. Longmans, Green, and Co., London. Reprint: Ch'eng Wen Publishing Company, Taipei. 1971.

- Leitner, G. W. 1893. Dardistan in 1866, 1886 and 1893: Being An Account of the History, Religions, Customs, Legends, Fables and Songs of Gilgit, Chilas, Kandia (Gabrial) Yasin, Chitral, Hunza, Nagyr and other parts of the Hindukush, as also a supplement to the second edition of The Hunza and Nagyr Handbook. And An Epitome of Part III of the author's The Languages and Races of Dardistan. First Reprint 1978. Manjusri Publishing House, New Delhi.

- Muhammad, Gulam. 1980. Festivals and Folklore of Gilgit. National Institute of Folk Heritage, Islamabad.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Imperial Gazetteer of India. Provincial Series: Kashmir and Jammu

- Shri Badat The Cannibal King A Buddhist Jataka from Gilgit

- Among Muslims: Meetings at the frontiers of Pakistan by Kathleen Jamie (2002) ISBN 978-0953522774

- From Colonialism to Postcolonial Colonialism: Changing Modes of Domination in the Northern Areas of Pakistan by Martin Sokefield. The Journal of Asian Studies 64 no 4. (November 2005):939-973. 2005 by the Association of Asian Studies, Inc.

External links

- Official Website of the Gilgit Baltistan Tourism Department

- Official Website of the Government of Gilgit Baltistan

- Gilgit Nomination, UNESCO, the Memory of the World Register entry document

- Britannica Gilgit

- Template:Wikitravel

Template:Buddhism2 Template:Capitals in Pakistan

35°55′N 74°18′E / 35.917°N 74.300°E

]