Sun: Difference between revisions

Revert to revision 45943965 using popups |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 331: | Line 331: | ||

[[cy:Haul]] |

[[cy:Haul]] |

||

[[da:Solen]] |

[[da:Solen]] |

||

[[pdc:Sunn]] |

|||

[[de:Sonne]] |

[[de:Sonne]] |

||

[[et:Päike]] |

[[et:Päike]] |

||

Revision as of 14:00, 29 March 2006

| |

| Observation data | |

|---|---|

| Mean distance from Earth |

149.6×106 km (92.95×106 mi) (8.31 minutes at the speed of light) |

| Visual brightness (V) | −26.8m |

| Absolute magnitude | 4.8m |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| Mean distance from Milky Way core |

~2.5×1017 km (26,000-28,000 light-years) |

| Galactic period | 2.25-2.50×108 a |

| Velocity | 217 km/s orbit around the center of the Galaxy, 20 km/s relative to average velocity of other stars in stellar neighborhood |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Mean diameter | 1.392×106 km (109 Earth diameters) |

| Circumference | 4.373×106 km (342 Earth diameters) |

| Oblateness | 9×10−6 |

| Surface area | 6.09×1012 km² (11,900 Earths) |

| Volume | 1.41×1018 km³ (1,300,000 Earths) |

| Mass | 1.9891×1030 kg (332,950 Earths) |

| Density | 1.408 g/cm³ |

| Surface gravity | 273.95 m s-2 (27.9 g) |

| Escape velocity from the surface |

617.54 km/s |

| Surface temperature | 5780 K |

| Temperature of corona | 5 MK |

| Core temperature | ~13.6 MK |

| Luminosity (Lsol) | 3.827×1026 W 3.9×1028 lm or 100 lm/W efficacy |

| Mean Intensity (Isol) | 2.009×107 W m-2 sr-1 |

| Rotation characteristics | |

| Obliquity | 7.25° (to the ecliptic) 67.23° (to the galactic plane) |

| Right ascension of North pole[1] |

286.13° (19 h 4 min 30 s) |

| Declination of North pole |

+63.87° (63°52' North) |

| Rotation period at equator |

25.3800 days (25 d 9 h 7 min 13 s)[1] |

| Rotation velocity at equator |

7174 km/h |

| Photospheric composition (by mass) (All in the plasma state) | |

| Hydrogen | 73.46 % |

| Helium | 24.85 % |

| Oxygen | 0.77 % |

| Carbon | 0.29 % |

| Iron | 0.16 % |

| Neon | 0.12 % |

| Nitrogen | 0.09 % |

| Silicon | 0.07 % |

| Magnesium | 0.05 % |

| Sulfur | 0.04 % |

The Sun is the spectral type G2V yellow star at the center of Earth's solar system. The Earth and other matter (including other planets, asteroids, meteoroids, comets and dust) orbit the Sun. Different latitudes of the Sun rotate at different rates; a point on the equator takes 25 days to complete a rotation, while a point at a pole takes 36 days. The resultant torsion creates the Sun's very strong magnetic field, which in turn drives the 11-year cycle of solar activity. The Sun accounts for more than 99% of the solar system's mass. Energy from the Sun has supported almost all life on Earth through photosynthesis since the appearance of the first organisms. Humans use sunlight for eyesight, warmth, growing crops, and powering solar cells.

The Sun is a ball of plasma with a diameter of 1.392 million km (864,950 mi) and a mass of about 2.0×1030 kg, which is somewhat greater than that of an average star in the Milky Way galaxy. About 74% of its mass is hydrogen, with 25% helium, and the rest made up of trace quantities of heavier elements. The Sun is about 4.6 billion (109) years old and is about halfway through its main sequence evolution, during which nuclear fusion reactions in its core fuse hydrogen into helium. About 5 million tons of matter are converted into energy within the Sun's core every second, producing neutrinos and solar radiation. In about 5 billion years, the Sun will evolve into a red giant and then a white dwarf, creating a planetary nebula in the process.

The Sun is a magnetically active star: it supports a strong, changing magnetic field that varies year-to-year and reverses direction about every eleven years. The magnetic field gives rise to many effects that are collectively called solar activity, including sunspots on the surface of the Sun, solar flares, and variations in the solar wind that carries material through the solar system. Effects of solar activity on the Earth include auroras at moderate to high latitudes, and disruption of radio communications and electric power. Solar activity is thought to have played a large role in the formation and evolution of the solar system, and strongly affects the structure of Earth's outer atmosphere.

Although it is the nearest star to Earth and has been intensively studied by scientists, many questions about the Sun remain unanswered, such as why its outer atmosphere has a temperature of over 1 million K when its visible surface (the photosphere) has a temperature of just 6,000 K. Current topics of scientific study include the sun's regular cycle of sunspot activity, the physics and origin of solar flares and prominences, the magnetic interaction between the chromosphere and the corona, and the origin of the solar wind.

General information

The sun has a spectral class of G2V. "G2" means that it has a surface temperature of approximately 5,500 K, giving it a yellow color, and that its spectrum contains lines of ionized and neutral metals as well as very weak hydrogen lines. The "V" suffix indicates that the Sun, like most stars, is a main sequence star. This means that it generates its energy by nuclear fusion of hydrogen nuclei into helium and is in a state of hydrostatic balance, neither contracting nor expanding over time.

The Sun will spend a total of approximately 10 billion years as a main sequence star. Its current age, determined using computer models of stellar evolution and nucleocosmochronology, is thought to be about 4.57 billion years.[2] The Sun orbits the center of the Milky Way galaxy at a distance of about 25,000 to 28,000 light-years from the galactic center, completing one revolution in about 225–250 million years. The orbital speed is 220 km/s, equivalent to one light-year every 1,400 years, and one AU every 8 days.[3]

The Sun is a third generation star, whose formation may have been triggered by shockwaves from a nearby supernova. This is suggested by a high abundance of heavy elements such as gold and uranium in the solar system; these elements could most plausibly have been produced by endergonic nuclear reactions during a supernova, or by transmutation via neutron absorption inside a massive second-generation star.

The Sun does not have enough mass to explode as a supernova, and its mass is below the Chandrasekhar limit. Instead, in 4–5 billion years, it will enter a red giant phase, its outer layers expanding as the hydrogen fuel in the core is consumed and the core contracts and heats up. Helium fusion will begin when the core temperature reaches about 3×108 K. While it is likely that the expansion of the outer layers of the Sun will reach the current position of Earth's orbit, recent research suggests that mass lost from the Sun earlier in its red giant phase will cause the Earth's orbit to move further out, preventing it from being engulfed. Following the red giant phase, intense thermal pulsations will cause the Sun to throw off its outer layers, forming a planetary nebula. The Sun will then evolve into a white dwarf, slowly cooling over eons. This stellar evolution scenario is typical of low- to medium-mass stars.[4]

Sunlight is the main source of energy near the surface of Earth. The solar constant is the amount of power that the Sun deposits per unit area that is directly exposed to sunlight. The solar constant is equal to approximately 1,370 watts per square meter of area at a distance of one AU from the Sun (that is, on or near Earth). Sunlight on the surface of Earth is attenuated by the Earth's atmosphere so that less power arrives at the surface—closer to 1,000 watts per directly exposed square meter in clear conditions when the Sun is near its zenith. This energy can be harnessed via a variety of natural and synthetic processes—photosynthesis by plants captures the energy of sunlight and converts it to chemical form (oxygen and reduced carbon compounds), while direct heating or electrical conversion by solar cells are used by solar power equipment to generate electricity or to do other useful work. The energy stored in petroleum and other fossil fuels was originally converted from sunlight by photosynthesis in the distant past.

Observed from Earth, the path of the Sun across the sky varies throughout the year. The shape described by the Sun's position, considered at the same time each day for a complete year, is called the analemma and resembles a figure 8 aligned along a North/South axis. While the most obvious variation in the Sun's apparent position through the year is a North/South swing over 47 degrees of angle (due to the 23.5-degree tilt of the Earth with respect to the Sun), there is an East/West component as well. The North/South swing in apparent angle is the main source of seasons on Earth.

The Sun is sometimes referred to by its Latin name Sol or by its Greek name Helios. Its astronomical/astrological symbol is a circle with a point at its center: . Some ancient peoples of the world considered it a planet.

Structure

The Sun is a near-perfect sphere, with an oblateness estimated at about 9 millionths,[5] which means that its polar diameter differs from its equatorial diameter by only 10 km. While the Sun does not rotate as a solid body (the rotational period is 25 days at the equator and about 35 days at the poles), it takes approximately 28 days to complete one full rotation; the centrifugal effect of this slow rotation is 18 million times weaker than the surface gravity at the Sun's equator. Tidal effects from the planets do not significantly affect the shape of the Sun, although the Sun itself orbits the center of mass of the solar system, which is located nearly a solar radius away from the center of the Sun mostly because of the large mass of Jupiter.

The Sun does not have a definite boundary as rocky planets do; the density of its gases drops approximately exponentially with increasing distance from the center of the Sun. Nevertheless, the Sun has a well-defined interior structure, described below. The Sun's radius is measured from its center to the edge of the photosphere. This is simply the layer below which the gases are thick enough to be opaque but above which they are transparent; the photosphere is the surface most readily visible to the naked eye. Most of the Sun's mass lies within about 0.7 radii of the center.

The solar interior is not directly observable, and the Sun itself is opaque to electromagnetic radiation. However, just as seismology uses waves generated by earthquakes to reveal the interior structure of the Earth, the discipline of helioseismology makes use of pressure waves traversing the Sun's interior to measure and visualize the Sun's inner structure. Computer modeling of the Sun is also used as a theoretical tool to investigate its deeper layers.

Core

At the center of the Sun, where its density reaches up to 150,000 kg/m3 (150 times the density of water on Earth), thermonuclear reactions (nuclear fusion) convert hydrogen into helium, releasing the energy that keeps the Sun in a state of equilibrium. About 8.9 ×1037 protons (hydrogen nuclei) are converted into helium nuclei every second, releasing energy at the matter-energy conversion rate of 4.26 million tonnes per second, 383 yottawatts (383 ×1024 W) or 9.15 ×1010 megatons of TNT per second. The fusion rate in the core is in a self-correcting equilibrium: a slightly higher rate of fusion would cause the core to heat up more and expand slightly against the weight of the outer layers, reducing the fusion rate and correcting the perturbation; and a slightly lower rate would cause the core to shrink slightly, increasing the fusion rate and again reverting it to its present level.

The core extends from the center of the Sun to about 0.2 solar radii, and is the only part of the Sun in which an appreciable amount of heat is produced by fusion; the rest of the star is heated by energy that is transferred outward. All of the energy produced by interior fusion must travel through many successive layers to the solar photosphere before it escapes into space.

The high-energy photons (gamma and X-rays) released in fusion reactions take a long time to reach the Sun's surface, slowed down by the indirect path taken, as well as by constant absorption and reemission at lower energies in the solar mantle. Estimates of the "photon travel time" range from as much as 50 million years[6] to as little as 17,000 years.[7] After a final trip through the convective outer layer to the transparent "surface" of the photosphere, the photons escape as visible light. Each gamma ray in the Sun's core is converted into several million visible light photons before escaping into space. Neutrinos are also released by the fusion reactions in the core, but unlike photons they very rarely interact with matter, so almost all are able to escape the Sun immediately. For many years measurements of the number of neutrinos produced in the Sun were much lower than theories predicted, a problem which was recently resolved through a better understanding of the effects of neutrino oscillation.

Radiation zone

From about 0.2 to about 0.7 solar radii, solar material is hot and dense enough that thermal radiation is sufficient to transfer the intense heat of the core outward. In this zone there is no thermal convection; while the material grows cooler as altitude increases, this temperature gradient is slower than the adiabatic lapse rate and hence cannot drive convection. Heat is transferred by radiation—ions of hydrogen and helium emit photons, which travel a brief distance before being reabsorbed by other ions.

Convection zone

From about 0.7 solar radii to 1.0 solar radii, the material in the Sun is not dense enough or hot enough to transfer the heat energy of the interior outward via radiation. As a result, thermal convection occurs as thermal columns carry hot material to the surface (photosphere) of the Sun. Once the material cools off at the surface, it plunges back downward to the base of the convection zone, to receive more heat from the top of the radiative zone. Convective overshoot is thought to occur at the base of the convection zone, carrying turbulent downflows into the outer layers of the radiative zone.

The thermal columns in the convection zone form an imprint on the surface of the Sun, in the form of the solar granulation and supergranulation. The turbulent convection of this outer part of the solar interior gives rise to a "small-scale" dynamo that produces magnetic north and south poles all over the surface of the Sun.

Photosphere

The visible surface of the Sun, the photosphere, is the layer below which the Sun becomes opaque to visible light. Above the photosphere visible sunlight is free to propagate into space, and its energy escapes the Sun entirely. The change in opacity is due to the decreasing amount of H− ions, which absorb visible light easily. Conversely, the visible light we see is produced as electrons react with hydrogen atoms to produce H− ions. Sunlight has approximately a black-body spectrum that indicates its temperature is about 6,000 K, interspersed with atomic absorption lines from the tenuous layers above the photosphere. The photosphere has a particle density of about 1023/m3 (this is about 1% of the particle density of Earth's atmosphere at sea level).

During early studies of the optical spectrum of the photosphere, some absorption lines were found that did not correspond to any chemical elements then known on Earth. In 1868, Norman Lockyer hypothesized that these absorption lines were due to a new element which he dubbed "helium", after the Greek Sun god Helios. It was not until 25 years later that helium was isolated on Earth.[8]

Atmosphere

The parts of the Sun above the photosphere are referred to collectively as the solar atmosphere. They can be viewed with telescopes operating across the electromagnetic spectrum, from radio through visible light to gamma rays, and comprise five principal zones: the temperature minimum, the chromosphere, the transition region, the corona, and the heliosphere. The heliosphere, which may be considered the tenuous outer atmosphere of the Sun, extends outward past the orbit of Pluto to the heliopause, where it forms a sharp shock front boundary with the interstellar medium. The chromosphere, transition region, and corona are much hotter than the surface of the Sun; the reason why is not yet known.

The coolest layer of the Sun is a temperature minimum region about 500 km above the photosphere, with a temperature of about 4,000 K. This part of the Sun is cool enough to support simple molecules such as carbon monoxide and water, which can be detected by their absorption spectra. Above the temperature minimum layer is a thin layer about 2,000 km thick, dominated by a spectrum of emission and absorption lines. It is called the chromosphere from the Greek root chroma, meaning color, because the chromosphere is visible as a colored flash at the beginning and end of total eclipses of the Sun. The temperature in the chromosphere increases gradually with altitude, ranging up to around 100,000 K near the top.

Above the chromosphere is a transition region in which the temperature rises rapidly from around 100,000 K to coronal temperatures closer to one million K. The increase is due to a phase transition as helium within the region becomes fully ionized by the high temperatures. The transition region does not occur at a well-defined altitude. Rather, it forms a kind of nimbus around chromospheric features such as spicules and filaments, and is in constant, chaotic motion. The transition region is not easily visible from Earth's surface, but is readily observable from space by instruments sensitive to the far ultraviolet portion of the spectrum.

The corona is the extended outer atmosphere of the Sun, which is much larger in volume than the Sun itself. The corona merges smoothly with the solar wind that fills the solar system and heliosphere. The low corona, which is very near the surface of the Sun, has a particle density of 1014/m3–1016/m3. (Earth's atmosphere near sea level has a particle density of about 2x1025/m3.) The temperature of the corona is several megakelvins. While no complete theory yet exists to account for the temperature of the corona, at least some of its heat is known to be due to magnetic reconnection.

The heliosphere extends from approximately 20 solar radii (0.1 AU) to the outer fringes of the solar system. Its inner boundary is defined as the layer in which the flow of the solar wind becomes superalfvénic—that is, where the flow becomes faster than the speed of Alfvén waves. Turbulence and dynamic forces outside this boundary cannot affect the shape of the solar corona within, because the information can only travel at the speed of Alfvén waves. The solar wind travels outward continuously through the heliosphere, forming the solar magnetic field into a spiral shape, until it impacts the heliopause more than 50 AU from the Sun. In December 2004, the Voyager 1 probe passed through a shock front that is thought to be part of the heliopause. Both of the Voyager probes have recorded higher levels of energetic particles as they approach the boundary.[9]

Solar activity

Sunspots and the solar cycle

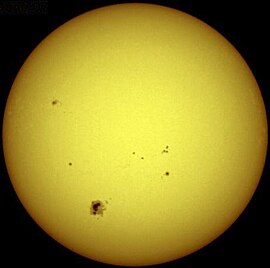

When observing the Sun with appropriate filtration, the most immediately visible features are usually its sunspots, which are well-defined surface areas that appear darker than their surroundings due to lower temperatures. Sunspots are regions of intense magnetic activity where energy transport is inhibited by strong magnetic fields. They are often the source of intense flares and coronal mass ejections. The largest sunspots can be tens of thousands of kilometres across.

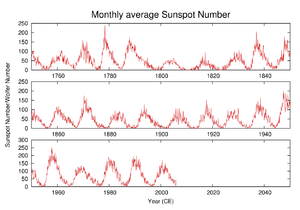

The number of sunspots visible on the Sun is not constant, but varies over a 10-12 year cycle known as the Solar cycle. At a typical solar minimum, few sunspots are visible, and occasionally none at all can be seen. Those that do appear are at high solar latitudes. As the sunspot cycle progresses, the number of sunspots increases and they move closer to the equator of the Sun, a phenomenon described by Spörer's law. Sunspots usually exist as pairs with opposite magnetic polarity. The polarity of the leading sunspot alternates every solar cycle, so that it will be a north magnetic pole in one solar cycle and a south magnetic pole in the next.

The solar cycle has a great influence on space weather, and seems also to have a strong influence on the Earth's climate. Solar minima tend to be correlated with colder temperatures, and longer than average solar cycles tend to be correlated with hotter temperatures. In the 1600s, the solar cycle appears to have stopped entirely for several decades; very few sunspots were observed during the period. During this era, which is known as the Maunder minimum or Little Ice Age, Europe experienced very cold temperatures.[10] Earlier extended minima have been discovered through analysis of tree rings and also appear to have coincided with lower-than-average global temperatures.

Effects on Earth

Solar activity has several effects on the Earth and its surroundings. Because the Earth has a magnetic field, charged particles from the solar wind cannot impact the atmosphere directly, but are instead deflected by the magnetic field and aggregate to form the Van Allen belts. The Van Allen belts consist of an inner belt composed primarily of protons and an outer belt composed mostly of electrons. Radiation within the Van Allen belts can occasionally damage satellites passing through them.

The Van Allen belts form arcs around the Earth with their tips near the north and south poles. The most energetic particles can 'leak out' of the belts and strike the Earth's upper atmosphere, causing aurorae, known as aurorae borealis in the northern hemisphere and aurorae australis in the southern hemisphere. In periods of normal solar activity, aurorae can be seen in oval-shaped regions centred on the magnetic poles and lying roughly at a geomagnetic latitude of 65°, but at times of high solar activity the auroral oval can expand greatly, moving towards the equator. Aurorae borealis have been observed from locales as far south as Mexico.

Predicting the solar cycle

Because the sunspot cycle is slightly chaotic it is difficult to determine in advance how strong a solar cycle will be or when it will occur. In March 2006, Mausumi Dikpati and collaborators at NCAR/HAO made the world's first physics-based prediction of the next solar cycle, based on simulations of the solar dynamo in the manner of terrestrial weather prediction. The next solar cycle (called 'Cycle 24' because it will be the 24th since regular sunspot observations began in Europe) is predicted to arrive around a year late (in late 2007 or early 2008) and to be 30%-50% stronger than the previous solar cycle (which began in 1995 and peaked in 2001).[11]

Theoretical problems

Solar neutrino problem

For many years the number of solar electron neutrinos detected on Earth was only a third of the number expected, according to theories describing the nuclear reactions in the Sun. This anomalous result was termed the solar neutrino problem. Theories proposed to resolve the problem either tried to reduce the temperature of the Sun's interior to explain the lower neutrino flux, or posited that electron neutrinos could oscillate, that is, change into undetectable tauon and muon neutrinos as they traveled between the Sun and the Earth.[12] Several neutrino observatories were built in the 1980s to measure the solar neutrino flux as accurately as possible, including the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory and Kamiokande. Results from these observatories eventually led to the discovery that neutrinos have a very small rest mass and can indeed oscillate.[13]

Coronal heating problem

The optical surface of the Sun (the photosphere) is known to have a temperature of approximately 6,000 K. Above it lies the solar corona at a temperature of 1,000,000 K. The high temperature of the corona shows that it is heated by something other than the photosphere.

It is thought that the energy necessary to heat the corona is provided by turbulent motion in the convection zone below the photosphere, and two main mechanisms have been proposed to explain coronal heating. The first is wave heating, in which sound, gravitational and magnetohydrodynamic waves are produced by turbulence in the convection zone. These waves travel upward and dissipate in the corona, depositing their energy in the ambient gas in the form of heat. The other is magnetic heating, in which magnetic energy is continuously built up by photospheric motion and released through magnetic reconnection in the form of large solar flares and myriad similar but smaller events.[14]

Currently, it is unclear whether waves are an efficient heating mechanism. All waves except Alfven waves have been found to dissipate or refract before reaching the corona.[15] In addition, Alfven waves do not easily dissipate in the corona. Current research focus has therefore shifted towards flare heating mechanisms. One possible candidate to explain coronal heating is continuous flaring at small scales,[16] but this remains an open topic of investigation.

Faint young sun problem

Theoretical models of the sun's development suggest that 3.8 to 2.5 billion years ago, during the Archean period, the Sun was only about 75% as bright as it is today. Such a weak star would not have been able to sustain liquid water on the Earth's surface, and thus life should not have been able to develop. However, the geological record demonstrates that the Earth has remained at a fairly constant temperature throughout its history, and in fact that the young Earth was somewhat warmer than it is today. The general consensus among scientists is that the young Earth's atmosphere contained much larger quantities of greenhouse gases (such as carbon dioxide and/or ammonia) than are present today, which trapped enough heat to compensate for the lesser amount of solar energy reaching the planet.[17]

Magnetic field

All matter in the Sun is in the form of gas and plasma due to its high temperatures. This makes it possible for the Sun to rotate faster at its equator (about 25 days) than it does at higher latitudes (about 35 days near its poles). The differential rotation of the Sun's latitudes causes its magnetic field lines to become twisted together over time, causing magnetic field loops to erupt from the Sun's surface and trigger the formation of the Sun's dramatic sunspots and solar prominences (see magnetic reconnection). This twisting action gives rise to the solar dynamo and an 11-year solar cycle of magnetic activity as the Sun's magnetic field reverses itself about every 11 years.

The influence of the Sun's rotating magnetic field on the plasma in the interplanetary medium creates the heliospheric current sheet, which separates regions with magnetic fields pointing in different directions. The plasma in the interplanetary medium is also responsible for the strength of the Sun's magnetic field at the orbit of the Earth. If space were a vacuum, then the Sun's 10-4 tesla magnetic dipole field would reduce with the cube of the distance to about 10-11 tesla. But satellite observations show that it is about 100 times greater at around 10-9 tesla. Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) theory predicts that the motion of a conducting fluid (e.g., the interplanetary medium) in a magnetic field, induces electric currents which in turn generates magnetic fields, and in this respect it behaves like an MHD dynamo.

History of solar observation

Early understanding of the Sun

Mankind's most fundamental understanding of the Sun is as the luminous disk in the heavens, whose presence above the horizon creates day and whose absence causes night. In many prehistoric and ancient cultures, the Sun was thought to be a solar deity or other supernatural phenomenon, and worship of the Sun was central to civilizations such as the Inca of South America and the Aztecs of what is now Mexico. Many ancient monuments were constructed with solar phenomena in mind; for example, stone megaliths accurately mark the summer solstice (some of the most prominent megaliths are located in Nabta Playa, Egypt, and at Stonehenge in England); the pyramid of El Castillo at Chichén Itzá in Mexico is designed to cast shadows in the shape of serpents climbing the pyramid at the vernal and autumn equinoxes. With respect to the fixed stars, the Sun appears from Earth to revolve once a year along the ecliptic through the zodiac, and so the Sun was considered by Greek astronomers to be one of the seven planets (Greek planetes, "wanderer"), after which the seven days of the week are named in some languages.

Development of modern scientific understanding

The concept of heliocentrism, which locates the Sun at the centre of the solar system, was first recorded in ancient India by Yajnavalkya (circa 9th century BC) in his work Shatapatha Brahmana, which referred to the Earth as a sphere and to the Sun as the "centre of spheres". Using this heliocentric model, Yajnavalkya measured the distance from the Sun to the Earth as 108 times the diameter of the Sun, which is very close to the modern measurement of 107.6 times the Sun's diameter. The calendar described in the text corresponds to an average tropical year of 365.2467 days, which is close to the modern value of 365.2422 days.

One of the first people in the Western world to offer a non-religious explanation for the sun was the Greek philosopher Anaxagoras, who reasoned that it was a giant flaming ball of metal even larger than the Peloponnese, and not the chariot of Helios as was commonly accepted in Greece at the time. Because Anaxagoras persisted in teaching what was considered heresy by his contemporaries, he was imprisoned by the authorities and sentenced to death (although he was later released through the intervention of Pericles).

In the 5th century CE, the Indian astronomer-mathematician Aryabhata completed his magnum opus, Aryabhatiya. In it, he proposed a heliocentric model in which the Earth was understood to be spinning on its axis, and the periods of the planets were given with respect to a stationary Sun. Aryabhata was also the first to advance the idea that the light from the Moon and the planets was reflected, having originated at the Sun. He also noted that the planets follow an elliptical orbit around the Sun; using this eccentric elliptical model of the planets, he was able to accurately calculate many astronomical constants, such as the timing of solar eclipses. Bhaskara (1114-1185) expanded on Aryabhata's heliocentric model in his treatise Siddhanta-Shiromani, in which he mentioned the law of gravity, and noted that the planets do not orbit the Sun at a uniform velocity. Arabic translations of Aryabhata's Aryabhatiya were available from the 8th century, while Latin translations were available from the 13th century. As these works achieved broad circulation before the time of Nicolaus Copernicus, the first major European proponent of heliocentrism, it is quite possible that Aryabhata's work influenced his ideas.

In the 16th century, Copernicus developed his own theory that the Earth orbited the Sun, rather than the other way around. Like his Greek antecedents, Copernicus' theory also brought him into conflict with the religious and political authorities of his time. In the early 17th century, Galileo pioneered telescopic observations of the Sun, making some of the first known observations of sunspots and positing that they were on the surface of the Sun (rather than small objects passing between the Earth and the Sun as had previously been supposed).[18] By observing the phases of Venus, Galileo was also able to demonstrate that the prevailing geocentric worldview was incorrect. Isaac Newton observed the Sun's light using a prism, demonstrating empirically that it was composed of light in many constituent colours.[19] In 1800, William Herschel discovered infrared radiation beyond the red part of the solar spectrum.[20] In the 1800s, spectroscopic studies of the Sun increased in sophistication, and Joseph von Fraunhofer made the first observations of absorption lines in the spectrum, the strongest of which are still often referred to as Fraunhofer lines. The first radio astronomy observations of the Sun were made in 1946,[21] and these were soon followed by X-ray observations.

In the early years of the modern scientific era, the source of the Sun's energy was a significant puzzle. Proposed sources included energy derived from the friction of the Sun's gas masses and gravitational potential energy released as the Sun continuously contracted. However, neither of these sources of energy could power the Sun for more than a few million years; geological evidence demonstrated that the Earth was several billion years old. Nuclear fusion was first proposed as the source of solar energy in the 1930s, when Hans Bethe completed detailed calculations that elucidated the two main energy-producing nuclear reactions that power the Sun.[22][23]

Solar space missions

The first satellites designed to observe the Sun were NASA's Pioneers 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9, which were launched between 1959 and 1968. These probes orbited the Sun at a distance similar to that of the Earth's orbit, and made the first detailed measurements of the solar wind and the solar magnetic field. Pioneer 9 operated for a particularly long period of time, transmitting data until 1987.[24]

In the 1970s, Helios 1 and the Skylab Apollo Telescope Mount provided scientists with significant new data on solar wind and the solar corona. The Helios 1 satellite was a joint U.S.-German probe that studied the solar wind from an orbit carrying the spacecraft inside Mercury's orbit at perihelion. The Skylab space station, launched by NASA in 1973, included a solar observatory module called the Apollo Telescope Mount that was operated by astronauts resident on the station. Skylab made the first time-resolved observations of the solar transition region and of ultraviolet emissions from the solar corona. Discoveries included the first observations of coronal mass ejections, then called "coronal transients", and of coronal holes, now known to be intimately associated with the solar wind.

In 1980, the Solar Maximum Mission was launched by NASA. This spacecraft was designed to observe gamma rays, X-rays and UV radiation from solar flares during a time of high solar activity. Just a few months after launch, however, an electronics failure caused the probe to go into standby mode, and it spent the next three years in this inactive state. In 1984 Space Shuttle Challenger mission STS-41C retrieved the satellite and repaired its electronics before re-releasing it into orbit. The Solar Maximum Mission subsequently acquired thousands of images of the solar corona before re-entering the Earth's atmosphere in June 1989.[25]

Japan's Yohkoh (Sunbeam) satellite, launched in 1991, observed solar flares at X-ray wavelengths. Mission data allowed scientists to identify several different types of flares, and also demonstrated that the corona away from regions of peak activity was much more dynamic and active than had previously been supposed. Yohkoh observed an entire solar cycle but went into standby mode when an annular eclipse in 2001 caused it to lose its lock on the Sun. It was destroyed by atmospheric reentry in 2005.[26]

One of the most important solar missions to date has been the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, jointly built by the European Space Agency and NASA and launched on December 2, 1995. Originally a two-year mission, SOHO has now operated for over ten years (as of 2006). It has proved so useful that a follow-on mission, the Solar Dynamics Observatory, is planned for launch in 2008. Situated at the Lagrangian point between the Earth and the Sun (at which the gravitational pull from both is equal), SOHO has provided a constant view of the Sun at many wavelengths since its launch. In addition to its direct solar observation, SOHO has enabled the discovery of large numbers of comets, mostly very tiny sungrazing comets which incinerate as they pass the Sun.[27]

All these satellites have observed the Sun from the plane of the ecliptic, and so have only observed its equatorial regions in detail. The Ulysses probe was launched in 1990 to study the Sun's polar regions. It first travelled to Jupiter, to 'slingshot' past the planet into an orbit which would take it far above the plane of the ecliptic. Serendipitously, it was well-placed to observe the collision of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 with Jupiter in 1994. Once Ulysses was in its scheduled orbit, it began observing the solar wind and magnetic field strength at high solar latitudes, finding that the solar wind from high latitudes was moving at about 750 km/s (slower than expected), and that there were large magnetic waves emerging from high latitudes which scattered galactic cosmic rays.[28]

Elemental abundances in the photosphere are well known from spectroscopic studies, but the composition of the interior of the Sun is more poorly understood. A solar wind sample return mission, Genesis, was designed to allow astronomers to directly measure the composition of solar material. Genesis returned to Earth in 2004 but was damaged by a crash landing after its parachute failed to deploy on reentry into Earth's atmosphere. Despite severe damage, some usable samples have been recovered from the spacecraft's sample return module and are undergoing analysis.

Sun observation and eye damage

Sunlight is very bright, and looking directly at the Sun with the naked eye for brief periods can be painful, but is generally not hazardous. Looking directly at the Sun causes phosphene visual artifacts and temporary partial blindness. It also delivers about 4 milliwatts of sunlight to the retina, slightly heating it and potentially (though not normally) damaging it. UV exposure gradually yellows the lens of the eye over a period of years and can cause cataracts, but those depend on general exposure to solar UV, not on whether one looks directly at the Sun.

Viewing the Sun through light-concentrating optics such as binoculars is very hazardous without an attenuating (ND) filter to dim the sunlight. Using a proper filter is important as some improvised filters pass UV rays that can damage the eye at high brightness levels. Unfiltered binoculars can deliver over 500 times more sunlight to the retina than does the naked eye, killing retinal cells almost instantly. Even brief glances at the midday Sun through unfiltered binoculars can cause permanent blindness.[29] One way to view the Sun safely is by projecting an image onto a screen using binoculars or a small telescope.

Partial solar eclipses are hazardous to view because the eye's pupil is not adapted to the unusually high visual contrast: the pupil dilates according to the total amount of light in the field of view, not by the brightest object in the field. During partial eclipses most sunlight is blocked by the Moon passing in front of the Sun, but the uncovered parts of the photosphere have the same surface brightness as during a normal day. In the overall gloom, the pupil expands from ~2 mm to ~6 mm, and each retinal cell exposed to the solar image receives about ten times more light than it would looking at the non-eclipsed sun. This can damage or kill those cells, resulting in small permanent blind spots for the viewer.[30] The hazard is insidious for inexperienced observers and for children, because there is no perception of pain: it is not immediately obvious that one's vision is being destroyed.

During sunrise and sunset, sunlight is attenuated through rayleigh and mie scattering of light by a particularly long passage through Earth's atmosphere, and the direct Sun is sometimes faint enough to be viewed directly without discomfort or safely with binoculars. Hazy conditions, atmospheric dust, and high humidity contribute to this atmospheric attenuation.

External links

- Current SOHO snapshots

- Far-Side Helioseismic Holography from Stanford

- NASA Eclipse homepage

- Nasa SOHO (Solar & Heliospheric Observatory) satellite FAQ

- Solar Sounds from Stanford

- Spaceweather.com

- Eric Weisstein's World of Astronomy - Sun

- The Position of the Sun

- A collection of solar movies

- The Institute for Solar Physics- Movies of Sunspots and spicules

- NASA/Marshall Solar Physics website

- Solar Position Algorithm and documentation from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory

- libnova - a celestial mechanics and astronomical calculation library

- NASA Podcast

References

- ^ a b Seidelmann, P.K. (2000). "Report Of The IAU/IAG Working Group On Cartographic Coordinates And Rotational Elements Of The Planets And Satellites: 2000" (HTML). Retrieved 2006-03-22.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bonanno, A. (2002). "The age of the Sun and the relativistic corrections in the EOS" (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics. 390: 1115–1118.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kerr, F.J. (1986). "Review of galactic constants" (PDF). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 221: 1023–1038.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pogge, Richard W. (1997). "The Once & Future Sun" (lecture notes). New Vistas in Astronomy. Retrieved 2005-12-07.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Godier, S. (2000). "The solar oblateness and its relationship with the structure of the tachocline and of the Sun's subsurface" (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics. 355: 365–374.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lewis, Richard (1983). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Universe. Harmony Books, New York. p. 65.

- ^ Plait, Phil (1997). "Bitesize Tour of the Solar System: The Long Climb from the Sun's Core" (HTML). Bad Astronomy. Retrieved 2006-03-22.

- ^ "Discovery of Helium" (HTML). Retrieved 2006-03-22.

- ^ European Space Agency (2005). "The Distortion of the Heliosphere: our Interstellar Magnetic Compass" (HTML). Retrieved 2006-03-22.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lean, J. (1992). "Estimating the Sun's radiative output during the Maunder Minimum". Geophysical Research Letters. 19: 1591–1594.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dikpati, M. (2006). "Predicting the strength of solar cycle 24 using a flux-transport dynamo-based tool". Geophysical Review Letters. 33 (5): L05102.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Haxton, W.C. (1995). "The Solar Neutrino Problem" (PDF). Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 33: 459–504.

- ^ Schlattl, H. (2001). "Three-flavor oscillation solutions for the solar neutrino problem". Physical Review D. 64 (1).

- ^ Alfven, H. (1947). "Magneto-hydrodynamic waves, and the heating of the solar corona". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society., 107, 211

- ^ Sturrock, P.A. (1981). "Coronal heating by stochastic magnetic pumping" (PDF). Astrophysical Journal.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help), 246, 331 - ^ Parker, E.N. (1988). "Nanoflares and the solar X-ray corona" (PDF). Astrophysical Journal., 330, 474

- ^ Kasting, J.F. (1986). "Climatic Consequences of Very High Carbon Dioxide Levels in the Earth's Early Atmosphere". Science. 234: 1383–1385.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Galileo Galilei (1564 - 1642)" (HTML). BBC. Retrieved 2006-03-22.

- ^ "Sir Isaac Newton (1643 - 1727)" (HTML). BBC. Retrieved 2006-03-22.

- ^ "Herschel Discovers Infrared Light" (HTML). Cool Cosmos. Retrieved 2006-03-22.

- ^ Ryle, M. (1946). "Solar radiation on 175Mc/s". Nature. 158: 339.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bethe, H. (1938). "On the Formation of Deuterons by Proton Combination". Physical Review. 54: 862–862.

- ^ Bethe, H. (1939). "Energy Production in Stars". Physical Review. 55: 434–456.

- ^ "Pioneer 6-7-8-9-E" (HTML). Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 2006-03-22.

- ^ St. Cyr, Chris (1998). "Solar Maximum Mission Overview" (HTML). Retrieved 2006-03-22.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (2005). "Result of Re-entry of the Solar X-ray Observatory "Yohkoh" (SOLAR-A) to the Earth's Atmosphere" (HTML). Retrieved 2006-03-22.

- ^ "SOHO Comets" (HTML). Retrieved 2006-03-22.

- ^ "Ulysses - Science - Primary Mission Results" (HTML). NASA. Retrieved 2006-03-22.

- ^ Marsh, J. C. D. (1982). "Observing the Sun in Safety" (PDF). J. Brit. Ast. Assoc., 92, 6

- ^ Espenak, F. "Eye Safety During Solar Eclipses - adapted from NASA RP 1383 Total Solar Eclipse of 1998 February 26, April 1996, p. 17" (HTML). NASA. Retrieved 2006-03-22.