Great Chicago Fire: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 173.15.120.173 to version by WolfmanSF. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (725974) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

The fire finally burned itself out, aided by diminishing winds and a light drizzle that began falling late on Monday night. From its origin at the O'Leary property, it had burned a path of nearly complete destruction of some 34 blocks to Fullerton Avenue on the north side.{{Citation needed|date=October 2009}} |

The fire finally burned itself out, aided by diminishing winds and a light drizzle that began falling late on Monday night. From its origin at the O'Leary property, it had burned a path of nearly complete destruction of some 34 blocks to Fullerton Avenue on the north side.{{Citation needed|date=October 2009}} |

||

==After the fire== |

|||

[[File:Chicago Fire Academy.jpg|thumb|right|230px|The sculpture on the site of the fire, with the Chicago Fire Academy in the background]] |

|||

[[File:Chicago Fire Landmark.jpg|230px|thumb|right|A marker commemorating the fire outside the Chicago Fire Academy]] |

|||

[[File:Municipal Flag of Chicago.svg|right|230px|thumb|Municipal [[Flag of Chicago]]]] |

|||

Once the fire had ended, the smoldering remains were still too hot for a survey of the damage to be completed for days. Eventually it was determined that the fire destroyed an area about four miles (6 km) long and averaging 3/4 mile (1 km) wide, encompassing more than {{convert|2000|acre|ha}}. Destroyed were more than {{convert|73|mi|km}} of roads, {{convert|120|mi|km}} of sidewalk, 2,000 lampposts, 17,500 buildings, and $222 million in property—about a third of the city's valuation. Of the 300,000 inhabitants, 90,000 were left homeless. Between two and three million books were destroyed from private library collections.<ref>Roland Tweet, Miss Gale's Books: The Beginnings of the Rock Island Public Library, (Rock Island, IL: Rock Island Public Library, 1997), 15.</ref> The fire was said by ''The Chicago Daily Tribune'' to have been so fierce that it surpassed the damage done by [[Fire of Moscow (1812)|Napoleon's siege of Moscow]] in 1812.<ref>{{Cite news | title = Cheer Up. | newspaper = Chicago Daily Tribune | pages = 2 | date = 1871-10-11}}</ref> Remarkably, some buildings did survive the fire, such as the then-new [[Chicago Water Tower]], which remains today as an unofficial memorial to the fire's destructive power. It was one of just five public buildings and one ordinary bungalow spared by the flames within the disaster zone. The O'Leary home and [[Holy Family Catholic Church (Chicago, Illinois)|Holy Family Church]], the [[Roman Catholic]] congregation of the O'Leary family, were both saved by shifts in the wind direction that kept them outside the burnt district. |

Once the fire had ended, the smoldering remains were still too hot for a survey of the damage to be completed for days. Eventually it was determined that the fire destroyed an area about four miles (6 km) long and averaging 3/4 mile (1 km) wide, encompassing more than {{convert|2000|acre|ha}}. Destroyed were more than {{convert|73|mi|km}} of roads, {{convert|120|mi|km}} of sidewalk, 2,000 lampposts, 17,500 buildings, and $222 million in property—about a third of the city's valuation. Of the 300,000 inhabitants, 90,000 were left homeless. Between two and three million books were destroyed from private library collections.<ref>Roland Tweet, Miss Gale's Books: The Beginnings of the Rock Island Public Library, (Rock Island, IL: Rock Island Public Library, 1997), 15.</ref> The fire was said by ''The Chicago Daily Tribune'' to have been so fierce that it surpassed the damage done by [[Fire of Moscow (1812)|Napoleon's siege of Moscow]] in 1812.<ref>{{Cite news | title = Cheer Up. | newspaper = Chicago Daily Tribune | pages = 2 | date = 1871-10-11}}</ref> Remarkably, some buildings did survive the fire, such as the then-new [[Chicago Water Tower]], which remains today as an unofficial memorial to the fire's destructive power. It was one of just five public buildings and one ordinary bungalow spared by the flames within the disaster zone. The O'Leary home and [[Holy Family Catholic Church (Chicago, Illinois)|Holy Family Church]], the [[Roman Catholic]] congregation of the O'Leary family, were both saved by shifts in the wind direction that kept them outside the burnt district. |

||

Revision as of 22:38, 14 November 2011

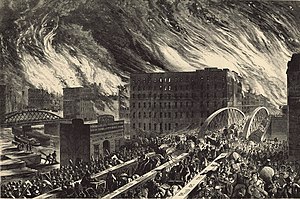

The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned from Sunday, October 8, to early Tuesday, October 10, 1871, killing hundreds and destroying about 4 square miles (10 km2) in Chicago, Illinois.[1] Though the fire was one of the largest U.S. disasters of the 19th century, the rebuilding that began almost immediately spurred Chicago's development into one of the most populous and economically important American cities.

On the municipal flag of Chicago, the second star commemorates the fire.[2] The exact cause and origin of the fire remain uncertain.

Origin

The fire started at about 9 p.m. on Sunday, October 8, in or around a small barn that bordered the alley behind 137 DeKoven Street.[3] The traditional account of the origin of the fire is that it was started by a cow kicking over a lantern in the barn owned by Patrick and Catherine O'Leary. Michael Ahern, the Chicago Republican reporter who created the cow story, admitted in 1893 that he had made it up because he thought it would make colorful copy.[4]

The fire's spread was aided by the city's overuse of wood for building, a drought prior to the fire, and strong winds from the southwest that carried flying embers toward the heart of the city. The city also made fatal errors by not reacting soon enough and citizens were apparently unconcerned when it began. The firefighters were also exhausted from fighting a fire that happened the day before.[5] The firefighters fought the fire through the entire day and became extremely exhausted. Eventually the fire jumped to a nearby neighborhood and began to devastate mansions, houses and apartments. Almost everything that crossed the fire's path was made of wood that had been dried out for quite a while. After two days of the city burning down it began to rain and doused the remaining fire. It is said that over 300 people died in the fire and over 100,000 were left homeless.

Spread of the blaze

The city's fire department did not receive the first alarm until 9:40 p.m., when a fire alarm was pulled at a pharmacy. The fire department was alerted when the fire was still small. When the blaze got bigger, the guard realized that there actually was a new fire and sent firefighters, but in the wrong direction.[citation needed]

Soon the fire had spread to neighboring frame houses and sheds. Superheated winds drove flaming brands northeastward.[citation needed]

When the fire engulfed a tall church west of the Chicago River, the flames crossed the south branch of the river. Helping the fire spread was firewood in the closely packed wooden buildings, ships lining the river, the city's elevated wood-plank sidewalks and roads, and the commercial lumber and coal yards along the river. The size of the blaze generated extremely strong winds and heat, which ignited rooftops far ahead of the actual flames.[citation needed]

The attempts to stop the fire were unsuccessful. The mayor had even called surrounding cities for help, but by that point the fire was simply too large to contain. When the fire destroyed the waterworks, just north of the Chicago River, the city's water supply was cut off, and the firefighters were forced to give up.[citation needed]

As the fire raged through the central business district, it destroyed hotels, department stores, Chicago's City Hall, the opera house and theaters, churches and printing plants. The fire continued spreading northward, driving fleeing residents across bridges on the Chicago River. There was mass panic as the blaze jumped the river's main stem and continued burning through homes and mansions on the city's north side. Residents fled into Lincoln Park and to the shores of Lake Michigan, where thousands sought refuge from the flames.[citation needed]

Philip Sheridan, a noted Union general in the American Civil War, was present during the fire and coordinated military relief efforts. The mayor, to calm the panic, placed the city under martial law, and issued a proclamation placing Sheridan in charge. As there were no widespread disturbances, martial law was lifted within a few days. Although Sheridan's personal residence was spared, all of his professional and personal papers were destroyed.[6]

The fire finally burned itself out, aided by diminishing winds and a light drizzle that began falling late on Monday night. From its origin at the O'Leary property, it had burned a path of nearly complete destruction of some 34 blocks to Fullerton Avenue on the north side.[citation needed]

Once the fire had ended, the smoldering remains were still too hot for a survey of the damage to be completed for days. Eventually it was determined that the fire destroyed an area about four miles (6 km) long and averaging 3/4 mile (1 km) wide, encompassing more than 2,000 acres (810 ha). Destroyed were more than 73 miles (117 km) of roads, 120 miles (190 km) of sidewalk, 2,000 lampposts, 17,500 buildings, and $222 million in property—about a third of the city's valuation. Of the 300,000 inhabitants, 90,000 were left homeless. Between two and three million books were destroyed from private library collections.[7] The fire was said by The Chicago Daily Tribune to have been so fierce that it surpassed the damage done by Napoleon's siege of Moscow in 1812.[8] Remarkably, some buildings did survive the fire, such as the then-new Chicago Water Tower, which remains today as an unofficial memorial to the fire's destructive power. It was one of just five public buildings and one ordinary bungalow spared by the flames within the disaster zone. The O'Leary home and Holy Family Church, the Roman Catholic congregation of the O'Leary family, were both saved by shifts in the wind direction that kept them outside the burnt district.

After the fire, 125 bodies were recovered. Final estimates of the fatalities ranged from 200–300, considered a small number for such a large fire. In later years, other disasters would claim many more lives: at least 605 died in the Iroquois Theater Fire in 1903; and, in 1915, 835 died in the sinking of the Eastland excursion boat in the Chicago River. Yet the Great Chicago Fire remains Chicago's most well-known disaster for the magnitude of the destruction and the city's recovery and growth.

Almost immediately, reform began in the city's fire standards, spurred by the efforts of leading insurance executives and fire prevention reformers such as Arthur C. Ducat and others. Chicago emerged from the fire with one of the country's leading fire fighting forces.

Land speculators, such as Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard, and business owners quickly set about rebuilding the city. Donations of money, food, clothing and furnishings arrived quickly from across the nation. The first load of lumber for rebuilding was delivered the day the last burning building was extinguished. Only 22 years later, Chicago hosted more than 21 million visitors during the World's Columbian Exposition. Another example of Chicago's rebirth from the Great Fire ashes is the now famed Palmer House hotel. The original building burned to the ground in the fire just 13 days after its grand opening. Without hesitating, Potter Palmer secured a loan and rebuilt the hotel in a lot across the street from the original, proclaiming it to be "The World's First Fireproof Building".

In 1956, the remaining structures on the original O'Leary property were torn down for construction of the Chicago Fire Academy, a training facility for Chicago firefighters located at 558 W. DeKoven Street. A bronze sculpture of stylized flames entitled Pillar of Fire by sculptor Egon Weiner was erected on the point of origin in 1961.[9]

Questions about the fire

Catherine O'Leary seemed the perfect scapegoat: she was an immigrant and Catholic, a combination which did not fare well in the political climate of the time in Chicago. This story was circulating in Chicago even before the flames had died out, and it was noted in the Chicago Tribune's first post-fire issue. Michael Ahern, the reporter who came up with the story, retracted the "cow-and-lantern" story in 1893, admitting it was fabricated.[10]

More recently, amateur historian Richard Bales has come to believe the fire started when Daniel "Pegleg" Sullivan, who first reported the fire, ignited hay in the barn while trying to steal milk. However, evidence recently reported in the Chicago Tribune by Anthony DeBartolo suggests Louis M. Cohn may have started the fire during a craps game. Cohn may also have admitted to starting the fire in a lost will.[11]

Dennis Regan was a resident of Chicago and a neighbor of the O'Learys. It is believed that he was an accomplice of Sullivan in the start of the Great Chicago Fire.[12]

Regan lived at 112 De Koven Street. As a witness of the fire, Regan testified that he heard someone outside yell that the O'Leary barn was on fire. Regan claimed that he attempted to warn the O'Learys and put out the fire.[12]

There are several holes in Regan's story, the biggest one is that he could not have known of the fire before the O'Learys. With this knowledge, some have assumed that Regan assisted Sullivan, the real culprit, in his attempt to protect the farm animals and extinguish the fire. Afterwards, it is believed, Sullivan and Regan tried to cover up their involvement.[13]

An alternative theory, first suggested in 1882, is that the Great Chicago Fire was caused by a meteor shower. At a 2004 conference of the Aerospace Corporation and the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, engineer and physicist Robert Wood suggested that the fire began when Biela's Comet broke up over the Midwest and rained down below. That four large fires took place, all on the same day, all on the shores of Lake Michigan (see Related Events), suggests a common root cause. Eyewitnesses reported sighting spontaneous ignitions, lack of smoke, "balls of fire" falling from the sky, and blue flames. According to Wood, these accounts suggest that the fires were caused by the methane that is commonly found in comets.[14]

However, since meteorites are not known to start or spread fires and are cool to the touch after reaching the ground, this theory has not found favor in the scientific community.[15][16] There are mundane explanations for various aspects of the behaviors of the Chicago and Peshtigo fires sometimes attributed to extraterrestrial intervention.[17] A common cause for the fires in the Midwest can be found in the fact that the area had suffered through a tinder-dry summer, so that winds from the front that moved in that evening were capable of generating rapidly expanding blazes from available ignition sources, which were plentiful in the region.[18][19] Methane-air mixtures become flammable only when the methane concentration exceeds 5%, at which point the mixtures also become explosive.[20][21] Methane gas is lighter than air and thus does not accumulate near the ground;[21] any localized pockets of methane in the open air would rapidly dissipate. Moreover, if a fragment of an icy comet were to strike the Earth, the most likely outcome, due to the low tensile strength of such bodies, would be for it to disintegrate in the upper atmosphere, leading to an air burst explosion analogous to that of the Tunguska event.[22]

Surviving structures

Related events

On that hot, dry and windy autumn day, three other major fires occurred along the shores of Lake Michigan at the same time as the Great Chicago Fire. Some 250 miles (400 km) to the north, the massive Peshtigo Fire consumed the town of Peshtigo, Wisconsin along with a dozen other villages. It killed 1,200 to 2,500 people and charred approximately 1.5 million acres (6,000 km²). The Peshtigo Fire remains the deadliest in American history but the remoteness of the region meant it was little noticed at the time. Across the lake to the east, the town of Holland, Michigan, and other nearby areas burned to the ground. Some 100 miles (160 km) to the north of Holland the lumbering community of Manistee, Michigan, also went up in flames in what became known as The Great Michigan Fire. Farther east, along the shore of Lake Huron, the Port Huron Fire swept through Port Huron, Michigan and much of Michigan's "Thumb". Also on October 9, 1871 a fire swept through the city of Urbana, Illinois, 140 miles (230 km) south of Chicago, destroying portions of its downtown area.[23] Windsor, Ontario likewise burned on October 12.

The city of Singapore, Michigan provided a large portion of the lumber to rebuild Chicago. As a result the town of Singapore was so heavily deforested that the area turned into barren sand dunes and the town had to be abandoned.

In popular culture

- The Chicago Fire, a Major League Soccer team, was founded on October 8, 1997, the 126th anniversary of the Great Chicago Fire. Earlier, another Chicago Fire team had played in the short-lived World Football League for one year under the same name, and yet another Chicago Fire played in the American Football Association.

- The University of Illinois at Chicago athletic teams are nicknamed the Flames, in commemoration of the Great Chicago Fire.[24] The site of the O'Leary barn is within three blocks of the campus' edge.

- Although set in Philadelphia, Theodore Dreiser's 1912 novel The Financier relays the nationwide impact the 1871 Chicago fire had on the stock markets and the financial world.

- The 1937 film In Old Chicago, is centered on the fire. It stars Tyrone Power, Alice Faye, and Don Ameche.

- The uncompleted Beach Boys album Smile (1966–67) included an instrumental track called "Mrs. O'Leary's Cow", which was originally conceived as the 'Fire' section of a proposed elemental suite. Group leader Brian Wilson produced the original basic track in late 1966 but reportedly abandoned the track after a fire broke out near the studio during the recording session. The track was eventually re-recorded for Wilson's solo 2004 remake of the album.

- There is also a 1976 Irwin Allen film themed on the fire and a science fiction storyline called Time Travelers, starring Sam Groom and Richard Basehart.

- The 1987 Williams pinball machine Fire! was themed upon the Great Chicago Fire. Williams is a Chicago-based company.

- In a 1998 episode of the TV series Early Edition, which aired on May 16, the lead character of Gary Hobson (played by actor Kyle Chandler) is knocked unconscious and awakens in 1871 Chicago, on the eve of the Great Chicago Fire.

- In his 1922 autobiography My Life and Loves, Frank Harris dedicates a whole chapter (7) to the Great Chicago Fire. It is supposed to be an eyewitness account, but it is difficult to verify.

- In 2008 screenwriter and Chicago native Jonathan Nolan announced he was writing a revenge story set in 1871 during the Great Chicago Fire for Warner Bros.[25]

- The fire was "re-enacted" regularly throughout the day as an attraction at the short lived (1960–1964) theme park Freedomland USA, near New York.

See also

- Dwight L. Moody – 19th century evangelist whose church was burnt down in the fire

- Horatio Spafford – Author of hymn "It Is Well With My Soul" who lost almost everything he owned in the fire

- Great Fire of London – 1666

- Great Toronto Fire – 1904

- Bombardment of Brussels – The bombardment in 1695 and the subsequent fire destroyed a third of the city

- Chicago Flood

- Fritz Anneke, retired U.S. colonel and veteran Forty-Eighter, died in December 1872 after having fallen into one of the numerous construction pits with which Chicago was plastered after the fire.

References

- ^ Bales, Richard (2004). "What do we know about the Great Chicago Fire?". Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- ^ "Municipal Flag of Chicago". Chicago Public Library. 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ^ Pierce, Bessie Louise (1957, rep. 2007). A History of Chicago: Volume III: The Rise of a Modern City, 1871–1893. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-226-66842-0.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The O'Leary Legend". Chicago History Museum. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ "The fire Fiend"". Chicago Daily Tribune. 1871-10-08. p. 3.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Morris, pp. 335–38.

- ^ Roland Tweet, Miss Gale's Books: The Beginnings of the Rock Island Public Library, (Rock Island, IL: Rock Island Public Library, 1997), 15.

- ^ "Cheer Up". Chicago Daily Tribune. 1871-10-11. p. 2.

- ^ Chicago Landmarks. retrieved December 14, 2006

- ^ Cromie, Robert (1994). The Great Chicago Fire. New York: Rutledge Hill Press. ISBN 1-55853-264-1.

- ^ Wykes, Alan (1964). The Complete Illustrated Guide to Gambling. New York: Doubleday. p. 147.

- ^ a b Bales, Richard F. (2005). The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O'Leary's Cow. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. pp. 127–130. ISBN 0786423587.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Chicago Fire". Chicago Public Library. 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-30.

- ^ Wood, Robert (February 3, 2004). "Did Biela's Comet Cause the Chicago and Midwest Fires?" (PDF). American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

- ^ Calfee, Mica (2003-02). "Was It A Cow Or A Meteorite?". Meteorite Magazine. 9 (1). Retrieved 2011-11-10.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Meteorites Don't Pop Corn". NASA Science. NASA. 2001-07-27. Retrieved 2011-11-10.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Bales, R. F. (April 2005). "Debunking Other Myths". The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O'Leary's Cow. McFarland. pp. 101–104. ISBN 978-0786423583. OCLC 68940921.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gess, D. (2003). Firestorm at Peshtigo: A Town, Its People, and the Deadliest Fire in American History. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0805072938. OCLC 52421495.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bales, R. F. (April 2005). "Debunking Other Myths". The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O'Leary's Cow. McFarland. p. 111. ISBN 978-0786423583. OCLC 68940921.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gases - Explosive and Flammability Concentration Limits". EngineeringToolBox.com. Retrieved 2011-11-13.

- ^ a b "Landfill Gas". Environmental Health Fact Sheet. Illinois Department of Public Health. Retrieved 2011-11-13.

- ^ Beech, M. (November 2006). "The Problem of Ice Meteorites" (PDF). Meteorite Quarterly. 12 (4): 17–19. Retrieved 2011-11-13.

- ^ "History Of The Urbana Fire Department". Urbana Firefighters Local 1147. 2008-03-07. Retrieved 2011-11-11.

- ^ "UIC Symbols: School Colors, Mascot, Song". UIC On-line Student Handbook. The Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. 2009. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ^ Jonathan Nolan Interview, The Prestige. retrieved May 15, 2009

Further reading

- Bales, Richard F. (2002). The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O'Leary's Cow. Jefferson, NC.: McFarland. ISBN 0786414243.

- Chicago and the Great Conflagration – Elias Colbert and Everett Chamberlin, 1871, 528 pp.

- "Who Caused the Great Chicago Fire? A Possible Deathbed Confession" – by Anthony DeBartolo, Chicago Tribune, October 8, 1997 and "Odds Improve That a Hot Game of Craps in Mrs. O'Leary's Barn Touched Off Chicago Fire" – by Anthony DeBartolo, Chicago Tribune, March 3, 1998

- "History of the Great Fires in Chicago and the West". – Rev. Edgar J. Goodspeed, D.D., 677 pp.

- Morris, Roy, Jr., Sheridan: The Life and Wars of General Phil Sheridan, Crown Publishing, 1992, ISBN 0-517-58070-5.

- "People & Events: The Great Fire of 1871". The Public Broadcasting System (PBS) Website. Retrieved September 3, 2004.

- The Great Conflagration – James W. Sheahan and George P. Upton, 1871, 458 pp.

- Shaw, William B. (1921). "The Chicago Fire – Fifty Years After". The Outlook. 129: 176–178. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Smith, Carl (1995). Urban Disorder and the Shape of Belief: The Great Chicago Fire, the Haymarket Bomb, and the Model Town of Pullman. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226764168.