1994 San Marino Grand Prix: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 468954095 by Jack Silver1000 (talk)(this is the official classifications, please stop changing this!) |

→Race: add comments to not change official classifications |

||

| Line 531: | Line 531: | ||

| [[WilliamsF1|Williams]]-[[Renault F1|Renault]] |

| [[WilliamsF1|Williams]]-[[Renault F1|Renault]] |

||

| 5 |

| 5 |

||

| Collision <!--- This is the official classification. Do not change! ---> |

|||

| Collision |

|||

| 1 |

| 1 |

||

| |

| |

||

| Line 567: | Line 567: | ||

| [[Simtek]]-[[Ford Motor Company|Ford]] |

| [[Simtek]]-[[Ford Motor Company|Ford]] |

||

| |

| |

||

| <!--- This is the official classification. Do not change! ---> |

|||

| |

|||

| |

| |

||

| |

| |

||

Revision as of 08:41, 2 January 2012

| 1994 San Marino Grand Prix | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Race 3 of 16 in the 1994 Formula One World Championship | |||

| |||

| Race details | |||

| Date | May 1, 1994 | ||

| Official name | 14° Gran Premio di San Marino | ||

| Location |

Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari Imola, Emilia-Romagna, Italy | ||

| Course | Permanent racing facility | ||

| Course length | 4.933 km (3.065 miles) | ||

| Distance | 58 laps, 286.114 km (177.77 miles) | ||

| Weather | Sunny | ||

| Pole position | |||

| Driver | Williams-Renault | ||

| Time | 1:21.548 | ||

| Fastest lap | |||

| Driver |

| Williams-Renault | |

| Time | 1:24.335 on lap 10 | ||

| Podium | |||

| First | Benetton-Ford | ||

| Second | Ferrari | ||

| Third | McLaren-Peugeot | ||

|

Lap leaders | |||

The 1994 San Marino Grand Prix (formally the 14° Gran Premio di San Marino) was a Formula One motor race held on May 1, 1994 at the Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari, Imola, Italy. It was the third race of the 1994 Formula One season. Events at this race proved to be a major turning point in both the 1994 season, and in the development of Formula 1 itself, particularly with regard to safety.

The race weekend was marred by the deaths of Austrian driver Roland Ratzenberger and of three-time world champion Ayrton Senna in separate accidents. Other incidents saw driver Rubens Barrichello injured and several mechanics and spectators injured. BBC Television commentator Murray Walker described it as "the blackest day for Grand Prix racing that I can remember".[1]

Michael Schumacher won the restarted race. In the press conference following the race, Schumacher said that he "couldn't feel satisfied, couldn't feel happy" with his win following the events that had occurred during the race weekend. Nicola Larini scored the first points of his career when he achieved a podium finish in second position. Mika Häkkinen finished third.

The race led to an increased emphasis on safety in the sport as well as the reforming of the Grand Prix Drivers' Association after a 12-year hiatus, and the changing of many track layouts and car designs. Since the race, numerous regulation changes have been made to slow Formula One cars down and new circuits, such as Bahrain International Circuit, incorporate large run-off areas to slow cars before they collide with a wall. Senna was given a state funeral in his home country of Brazil, where around 500,000 people lined the streets to watch the coffin pass. Italian prosecutors charged six people with manslaughter in connection with Senna's death, all of whom were later acquitted. The case took more than 11 years to conclude due to an appeal and a retrial following the original not guilty verdict.

Report

Qualifying

Friday qualifying

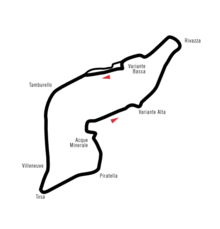

On Friday, April 29, during the first qualifying session to determine the starting order for the race,[2] Rubens Barrichello, a driver for Jordan, hit a kerb at the Variante Bassa corner at 140 mph (225 km/h), launching him into the air.[3] He hit the top of the tyre barrier, and was knocked unconscious. His Jordan rolled several times after landing before coming to rest upside down. Medical teams treated him at the crash site, and he was taken to the medical centre. He returned to the race meeting the next day, although his broken nose and a plaster cast on his arm forced him to sit out the rest of the race weekend. Ten years after the incident, Damon Hill, who drove for the Williams-Renault team at the time, described the feeling after the crash: "We all brushed ourselves off and carried on qualifying, reassured that our cars were tough as tanks and we could be shaken but not hurt."[4]

Saturday qualifying

Twenty minutes into the final qualifying session, Roland Ratzenberger failed to negotiate the Villeneuve curva in his Simtek; he subsequently hit the opposing concrete barrier wall almost head-on and was critically injured. Although the survival cell remained largely intact, the force of the impact inflicted a basal skull fracture. Ratzenberger, in his first season as a Formula One driver, had run over a kerb at the Acque Minerali chicane on his previous lap, the impact of which is believed to have damaged his front wing. Rather than return to the pitlane, he continued on another fast lap. Travelling at 190 mph (306 km/h) his car suffered a front wing failure leaving him unable to control it.[5]

The session was stopped whilst doctors attended to Ratzenberger. The session was restarted approximately 25 minutes later, but several teams—including Williams and Benetton—took no further part.[6] Later in hospital it was announced that Ratzenberger had died as a result of his multiple injuries. His death marked the first Formula One race weekend fatality since the 1982 Canadian Grand Prix when Riccardo Paletti was killed. It had been eight years since Elio de Angelis died testing a Brabham car at the Circuit Paul Ricard. Professor Sid Watkins, then head of the Formula One on-track medical team, recalled in his memoirs Ayrton Senna's reaction to the news, stating that "Ayrton broke down and cried on my shoulder."[7] Watkins tried to persuade Senna not to race the following day, asking "What else do you need to do? You have been world champion three times, you are obviously the quickest driver. Give it up and let's go fishing," but Ayrton was insistent, saying, "Sid, there are certain things over which we have no control. I cannot quit, I have to go on."[7]

Senna had qualified on pole position, ahead of championship leader Michael Schumacher. Gerhard Berger qualified in 3rd, and Senna's team-mate Damon Hill started from fourth position. A time posted by Ratzenberger before his fatal crash would have been sufficient for entry into the race starting from the 26th and final position on the grid.

Race

First start

At the start of the race, J.J. Lehto stalled his Benetton on the grid. Pedro Lamy, starting from further back on the grid, had his view of the stationary Benetton blocked by other cars and hit the back of Lehto's car, causing bodywork and tyres to fly into the air. Parts of the car went over the safety fencing designed to protect spectators at the startline causing minor injuries to nine people.[8] The incident caused the safety car to be deployed, with all the remaining competitors holding position behind it while travelling at a reduced speed. During this period, as a result of travelling at slower speeds, tyre temperatures dropped. At the drivers' briefing before the race, Senna, along with Gerhard Berger, had expressed concern that the safety car (itself only reintroduced in F1 in 1993) did not go fast enough to keep tyre temperatures high.[8] Once the track was reported clear of debris, the safety car was withdrawn and the race restarted with a rolling start. On the second lap after the restart, with Ayrton Senna leading Michael Schumacher, Senna's car left the road at the Tamburello corner, and after slowing from 190 mph (306 km/h) to 131 mph (211 km/h), hit the concrete wall.

At 2:17 p.m. local time, a red flag was shown to indicate the race was stopped and Sid Watkins arrived at the scene to treat Senna. When a race is stopped under a red flag cars must slow down and make their way back to the pit lane or starting grid until further notice. This protects race marshals and medical staff at the crash scene, and allows easier access for medical cars to the incident. Approximately 10 minutes after Senna's crash, the Larrousse team mistakenly[9] allowed one of their drivers, Érik Comas, to leave the pits despite the circuit being closed under red flags. Marshals frantically waved him down as he approached the scene of the accident travelling at "pretty much full speed".[10] Eurosport commentator John Watson described the incident as "the most ridiculous thing I have ever seen at any time in my life".[10] Comas avoided hitting any of the people or cars that were on the circuit but after going over towards Senna's accident scene, he was so distressed at what he saw that he withdrew from the race. The pictures shown of Senna being treated on the world feed (supplied by host broadcaster RAI) were very graphic, and the BBC switched to their own camera focused on the pit lane.[11] BBC commentator Murray Walker has frequently talked about how upsetting it was to have to talk to viewers while avoiding all mention of the distressing pictures he could see on the world feed. Senna was lifted from the wrecked Williams and airlifted to Maggiore Hospital in nearby Bologna. Medical teams continued to treat him during the flight. Thirty-seven minutes after the crash, at 2:55 p.m. local time, the race was restarted.

Second start

The results of the restarted race would be determined by the aggregate results of the aborted first race and the second race. From the restart, Gerhard Berger took the lead on track but Schumacher still led the race overall due to the amount of time he was ahead of Berger before the race was stopped. Schumacher took the lead on track on lap 12, and four laps later, Berger retired from the race with handling problems. Larini briefly took the lead as Schumacher pitted but the order was restored when Larini took his own pit stop.[12]

Ten laps from the finish the rear-right wheel came loose from Michele Alboreto's Minardi as it left the pit lane, striking two Ferrari and two Lotus mechanics, who were left needing hospital treatment.[13]

Michael Schumacher won the race ahead of Nicola Larini and Mika Häkkinen, giving him a maximum 30 points after 3 rounds of the 1994 Formula One season. It was the only podium finish of Larini's career, and the first of just two occasions when he scored world championship points. At the podium ceremony, out of respect for Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna, no champagne was sprayed.

Post-race

Two hours and 20 minutes after Schumacher crossed the finish line, at 6:40 p.m. local time, Dr. Maria Teresa Fiandri announced that Ayrton Senna had died. The official time of death was given, however, as 2:17 p.m. local time, meaning that Senna had been killed instantly.[14] The cause of death established by an autopsy is that a piece of the car's suspension pierced his helmet and skull.[15]

The 1994 Imola layout, which had been in place since 1981,[16] was never again used for a Formula One race. The circuit was heavily modified following the race, including a change at Tamburello—also the scene of major accidents for Gerhard Berger (1989) and Nelson Piquet (1987)—from a high speed corner to a much slower chicane. The FIA also changed the regulations governing Formula One car design, to the extent that the 1995 regulations required all teams to create completely new designs, as their 1994 cars could not be adapted to them.[17] The concern raised at the drivers briefing the morning of the race, by Senna and Berger, would lead to the Grand Prix Drivers' Association reforming at the following race, the 1994 Monaco Grand Prix. The GPDA, which was originally founded in 1961, had previously disbanded in 1982. The primary purpose of it reforming was to allow drivers to discuss safety issues with a view to improve standards following the incidents at Imola. The front two grid slots at the Monaco Grand Prix that year, which were painted with Brazilian and Austrian flags, were left clear in memory of the two drivers who had lost their lives, while both Williams and Simtek entered only one car each. Additionally, a minute of silence was observed before the race.

Senna was given a state funeral in São Paulo, Brazil on May 5, 1994. Approximately 500,000 people lined the streets to watch the coffin pass.[1] Senna's rival Alain Prost was among the pallbearers.[18] The majority of the Formula One community attended Senna's funeral; however the president of the sport's governing body, the FIA, Max Mosley attended the funeral of Ratzenberger instead which took place on May 7, 1994 in Salzburg, Austria.[19] Mosley said in a press conference ten years later, "I went to his funeral because everyone went to Senna's. I thought it was important that somebody went to his."[20]

In October 1996 FIA set about researching a driver restraint system for head-on impacts, in conjunction with McLaren and Mercedes-Benz. Mercedes contacted the makers of the HANS (Head and Neck Support) device, with a view to adapting it for Formula One. The HANS device was first released in 1991 and was designed to restrain the head and neck in the event of an accident to avoid basal skull fracture, the injury which killed Ratzenberger. Initial tests proved successful, and at the 2000 San Marino Grand Prix the final report was released which concluded that the HANS should be recommended for use. Its use was made compulsory from the start of the 2001 season.[21]

Senna remains the last driver to die in a Formula 1 accident, however two trackside marshals have been killed as a direct result of such crashes, at the 2000 Italian Grand Prix and the 2001 Australian Grand Prix.

Trial

Italian prosecutors brought legal proceedings against six people in connection with Senna's death. They were Frank Williams, Patrick Head and Adrian Newey of Williams; Fedrico Bendinelli representing the owners of the Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari; Giorgio Poggi as the circuit director and Roland Bruynseraede who was race director and sanctioned the circuit.[22] The trial verdict was given on December 16, 1997, clearing all six defendants of manslaughter charges.[23] The cause of Senna's accident was established by the court as the steering column breaking.[24] The column had been cut and welded back together at Senna's request in order for him to be more comfortable in the car.

Following the court's decision, an appeal was lodged by the state prosecutor against Patrick Head and Adrian Newey. On November 22, 1999, the appeal absolved Head and Newey of all charges, stating that no new evidence had come to light (there was missing data from the black box recorder on Senna's car due to damage, and 1.6 seconds of video from the onboard camera of Senna's car was unavailable because the broadcaster switched to another car's camera just before the accident), and so under Article 530 of the Italian Penal Code, the accusation had to be declared as "non-existent or the fact doesn't subsist".[25] This appeal result was annulled in January 2003, as the Court of Cassation believed that Article 530 was misinterpreted,[26] and a retrial was ordered. On May 27, 2005, Newey was acquitted of all charges while Head's case was "timed out" under a statute of limitations.[27] The Italian Court of Appeal, on April 13, 2007, stated the following in the verdict numbered 15050: "It has been determined that the accident was caused by a steering column failure. This failure was caused by badly designed and badly executed modifications. The responsibility of this falls on Patrick Head, culpable of omitted control". Even being found responsible for Senna's accident, Patrick Head wasn't arrested: in Italy the statute of limitation for manslaughter is 7 years and 6 months, and the final verdict was pronounced 13 years after the accident.[28]

Classification

Qualifying

| Pos | No | Driver | Team | Q1 Time | Q2 Time | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Williams-Renault | 1:21.548 | no time | — | |

| 2 | 5 | Benetton-Ford | 1:22.015 | 1:21.885 | +0.337 | |

| 3 | 28 | Ferrari | 1:22.113 | 1:22.226 | +0.565 | |

| 4 | 0 | Williams-Renault | 1:23.199 | 1:22.168 | +0.620 | |

| 5 | 6 | Benetton-Ford | 1:22.717 | 1:24.029 | +1.169 | |

| 6 | 27 | Ferrari | 1:22.841 | 1:23.006 | +1.293 | |

| 7 | 30 | Sauber-Mercedes | 1:23.119 | no time | +1.571 | |

| 8 | 7 | McLaren-Peugeot | 1:23.611 | 1:23.140 | +1.592 | |

| 9 | 3 | Tyrrell-Yamaha | 1:24.000 | 1:23.322 | +1.774 | |

| 10 | 29 | Sauber-Mercedes | 1:23.788 | 1:23.347 | +1.799 | |

| 11 | 10 | Footwork-Ford | 1:23.663 | 1:24.682 | +2.115 | |

| 12 | 4 | Tyrrell-Yamaha | 1:23.703 | 1:23.831 | +2.155 | |

| 13 | 8 | McLaren-Peugeot | 1:24.443 | 1:23.858 | +2.310 | |

| 14 | 23 | Minardi-Ford | 1:24.078 | 1:24.423 | +2.530 | |

| 15 | 24 | Minardi-Ford | 1:24.276 | 1:24.780 | +2.728 | |

| 16 | 9 | Footwork-Ford | 1:24.655 | 1:24.472 | +2.924 | |

| 17 | 25 | Ligier-Renault | 1:24.678 | 1:40.411 | +3.130 | |

| 18 | 20 | Larrousse-Ford | 1:26.295 | 1:24.852 | +3.304 | |

| 19 | 26 | Ligier-Renault | 1:24.996 | 1:25.160 | +3.448 | |

| 20 | 12 | Lotus-Mugen-Honda | 1:25.114 | 1:25.141 | +3.566 | |

| 21 | 15 | Jordan-Hart | 1:25.234 | 1:25.872 | +3.686 | |

| 22 | 11 | Lotus-Mugen-Honda | 1:26.453 | 1:25.295 | +3.747 | |

| 23 | 19 | Larrousse-Ford | 1:27.179 | 1:25.991 | +4.443 | |

| 24 | 31 | Simtek-Ford | 1:27.607 | 1:26.817 | +5.269 | |

| 25 | 34 | Pacific-Ilmor | 1:27.732 | 1:27.143 | +5.595 | |

| 26 | 32 | Simtek-Ford | 1:27.657 | 1:27.584 | +6.036 | |

| 27 | 33 | Pacific-Ilmor | 1:28.361 | 1:27.881 | +6.333 | |

| 28 | 14 | Jordan-Hart | 14:57.323 | no time | +13:35.775 | |

Source:[29]

| ||||||

Race

Standings after the race

|

|

Footnotes

- ^ a b "Race ace Senna killed in car crash". BBC News. 1994-05-01. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ Longmore, Andrew (1994-10-31). "Ayrton Senna: The Last Hours". The Times. News International. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ Hamilton, Maurice. Frank Williams. Macmillan. p. 232. ISBN 0-333-71716-3.

- ^ Hill, Damon (2004-04-17). "Had Ayrton foreseen his death?". The Times. London: News International. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ Spurgeon, Brad (1999-04-30). "5 Years After Senna's Crash, Racing Is Safer – Some Say Too Safe: Imola Still Haunts Formula One". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 2007-09-12. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ^ Kalff, Allard; Watson, John (commentators) (1994-04-30). Eurosport (Television production). Paris: Eurosport.

- ^ a b Hamilton, Maurice. Frank Williams. Macmillan. p. 234. ISBN 0-333-71716-3.

- ^ a b "A tragic weekend". The Times. London: News International. 2004-04-19. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ "TITLE REQUIRED". Autosport. 1994-05-05.

- ^ a b Watson, John (Commentator) (1994). Eurosport Live Grand Prix (Television). Eurosport.

- ^ Horton, Roger (2000). "There's Something about Murray". Autosport. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ "Grand Prix Results: San Marino GP, 1994". GP Encyclopedia. www.grandprix.com. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ Rider, Steve (Presenter) (1994). San Marino Grand Prix (Television). London, United Kingdom: BBC.

- ^ "Secrets of Senna's black box". Senna Files. www.ayrton-senna.com. 1997-03-18. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ Thomsen, Ian (1995-02-11). "Williams Says Italy May Cite Steering In Senna's Death". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 2006-11-23. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ "Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari - Imola". www.gpracing.net192.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ Wright, Peter (1995). "Preview of 1995 Formula1 Cars". www.grandprix.com. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ "Open Warfare". www.gpracing.net192.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ David Tremayne, Mark Skewis, Stuart Williams, Paul Fearnley (1994-04-05). "Track Topics". Motoring News. News Publications Ltd.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Max went to Roland's funeral". GPUpdate.net. 2004-04-23. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ^ Stonefeld, Ross (2001-02-21). "Helping Hans". AtlasF1. Haymarket.

- ^ Hamilton, Maurice. Frank Williams. Macmillan. p. 276. ISBN 0-333-71716-3.

- ^ "All six cleared in Senna trial". Senna Files. www.ayrton-senna.com. 1997-12-16. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ "Faulty Steering Caused Crash!". Senna Files. www.ayrton-senna.com. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ "Appeal absolves Head and Newey". Senna Files. www.ayrton-senna.com. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ "Senna death case back in court". BBC Sport. 2003-01-28. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ "Top designers acquitted on Senna". BBC Sport. 2005-05-27. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ "Senna, Head "responsabile" – Gazzetta dello Sport". Gazzetta.it. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ Henry, Alan (ed.) (1994). AUTOCOURSE 1994-95. Hazleton Publishing Ltd. pp. 128–129. ISBN 1-874557-95-0.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ "Race Results". Formula1.com. Formula One Administration. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

See also

External links

- Video of Senna's crash used in the Italian court case

- AtlasF1's 'The Races we Remember' Series:The 1990s

Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA