Eta Carinae: Difference between revisions

m →References: expand citation |

Added link to another image |

||

| Line 433: | Line 433: | ||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

{{Commons category|Eta Carinae}} |

{{Commons category|Eta Carinae}} |

||

* [http://www.flickr.com/photos/gsfc/6780345900/in/photostream NASA image released Feb. 24, 2012] |

|||

* [http://www.aavso.org/vstar/vsots/0400.shtml Variable Star Of The Month AAVSO. April, 2000: Eta Carinae] |

* [http://www.aavso.org/vstar/vsots/0400.shtml Variable Star Of The Month AAVSO. April, 2000: Eta Carinae] |

||

* [http://chjaa.bao.ac.cn/2003/Italy/33.pdf#search=%22Eta%20Carinae%20triple%20star%20system%22 'Eta Carinae — an evolved triple-star system?' by Wolfgang Kundt and Christoph Hillemanns] |

* [http://chjaa.bao.ac.cn/2003/Italy/33.pdf#search=%22Eta%20Carinae%20triple%20star%20system%22 'Eta Carinae — an evolved triple-star system?' by Wolfgang Kundt and Christoph Hillemanns] |

||

Revision as of 19:39, 27 February 2012

Hubble Space Telescope image showing Eta Carinae and the bipolar Homunculus Nebula which surrounds the star. The Homunculus was partly created in an eruption of Eta Carinae, the light from which reached Earth in 1843. Eta Carinae itself appears as the white patch near the center of the image, where the 2 lobes of the Homunculus touch. | |

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Carina |

| Right ascension | 10h 45m 03.591s[1] |

| Declination | −59° 41′ 04.26″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 4.47 (February 2011)[2] −0.8 to 7.9[3] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | WR pe |

| U−B color index | -0.45 |

| B−V color index | 0.61 |

| Variable type | LBV[3] binary or multiple star |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −25.0[1] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −7.6[1] mas/yr Dec.: 1.0[1] mas/yr |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | -5.45 to −5.74 |

| Details | |

| Mass | 100–150[4] M☉ |

| Radius | 85–195 [5] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 5 × 106(bolometric) L☉ |

| Temperature | 36–40,000 K |

| Age | ~ <3 × 106 years |

| Other designations | |

Eta Carinae (η Carinae or η Car) is a stellar system in the constellation Carina, about 7,500 to 8,000 light-years from the Sun. The system contains at least two stars, one of which is a Luminous Blue Variable (LBV), which during the early stages of its life had a mass of around 150 solar masses, of which it has lost at least 30 since. It is thought that a Wolf-Rayet star of approximately 30 solar masses exists in orbit around its larger companion star, although an enormous thick red nebula surrounding Eta Carinae makes it impossible to see optically. Its combined luminosity is about four million times that of the Sun and has an estimated system mass in excess of 100 solar masses.[7] It is not visible north of latitude 30°N and is circumpolar south of latitude 30°S. Because of its mass and the stage of life, it is expected to explode in a supernova or even hypernova in the astronomically near future.

Names

In traditional Chinese astronomy, Eta Carinae has the names Tseen She (from the Chinese 天社 [Mandarin: tiānshè] "Heaven's altar") and Foramen.[8] It is also known as 海山二 (Hǎi Shān èr, Template:Lang-en).[9], referring to Sea and Mountain, an asterism that Eta Carinae forms with s Carinae, λ Centauri and λ Muscae.[10]

Significance

This stellar system is currently one of the most massive that can be studied in great detail. Until recently, Eta Carinae was thought to be the most massive single star, but in 2005 it was realised to be a binary system.[11] The most massive star in the Eta Carinae multiple star system probably has more than 100 times the mass of the Sun.[12] Other known massive stars are more luminous and more massive.

Stars in the mass class of Eta Carinae produce more than a million times as much light as the Sun. They are quite rare — only a few dozen in a galaxy as big as the Milky Way. They are assumed to approach (or potentially exceed) the Eddington limit, i.e., the outward pressure of their radiation is almost strong enough to counteract gravity. Stars that are more than 120 solar masses exceed the theoretical Eddington limit, and their gravity is barely strong enough to hold in their radiation and gas.

Eta Carinae's chief significance for astrophysics is based on its giant eruption or supernova impostor event, which was observed around 1843. In a few years, Eta Carinae produced almost as much visible light as a supernova explosion, but it survived. Other supernova impostors have been seen in other galaxies, for example the possible false supernovae SN 1961v in NGC 1058[13] and SN 2006jc in UGC 4904,[14] which produced a false supernova, noted in October 2004. Significantly, SN 2006jc was destroyed in a supernova explosion two years later, observed on October 9, 2006.[15] The supernova impostor phenomenon may represent a surface instability[16] or a failed supernova. Eta Carinae's giant eruption was the prototype for this phenomenon, and after nearly 170 years the star's internal structure has not fully recovered.[citation needed]

Brightness variations

One remarkable aspect of Eta Carinae is its changing brightness. It is currently classified as a luminous blue variable (LBV) binary star due to peculiarities in its pattern of brightening and dimming.

When Eta Carinae was first catalogued in 1677 by Edmond Halley, it was of the 4th magnitude, but by 1730, observers noticed it had brightened considerably and was, at that point, one of the brightest stars in Carina. Subsequently it dimmed again and by 1782 it appeared to have reverted to its former obscurity. In 1820, it was observed to be growing in brightness again. By 1827, it had brightened more than tenfold and reached its greatest apparent brightness in April 1843. With a magnitude of −0.8, it was the second brightest star in the night-time sky (after Sirius at 8.6 light years away), despite its enormous distance of 7,000–8,000 light years. (To put the relationship in perspective, the relative brightness would be like comparing a candle (representing Sirius) at 14.5 meters (48 feet) to another light source (Eta Carinae) about 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) away, which would appear almost as bright as the candle.)

Eta Carinae sometimes has large outbursts, the last of which appeared in 1841, at around the time of its maximum brightness. The reason for these outbursts is not known. The most likely explanation is that they are caused by a build-up of radiation pressure from the star's enormous luminosity.[citation needed] After 1843, Eta Carinae faded and between about 1900 and 1940 it was only 8th magnitude, invisible to the naked eye.[17] A sudden and unexpected doubling of brightness was observed in 1998–1999. In 2007, at magnitude 5, Eta Carinae could be seen with the naked eye.[2]

In 2008, the formerly clockwork regularity of the dimming was upset.[18] Following its 5.52-year cycle, the star would normally have started its next dimming in January 2009, but the pattern was noticed starting early in July 2008 by the southern Gemini Observatory near La Serena, Chile. Spectrographic measurements showed an increase in blue light from superheated helium, which was formerly assumed to occur with the wind shock. However, if the cause is a binary star, it would be located too far away at this point in time for the wind to interact in so significant a fashion. There is some debate about the cause of the recent event.[18]

In 2010, astronomers Duane Hamacher and David Frew from Macquarie University in Sydney showed that the Boorong Aboriginal people of northwestern Victoria, Australia, witnessed the outburst of Eta Carinae in the 1840s and incorporated it into their oral traditions as "Collowgulloric War", the wife of "War" (Canopus, the Crow — pronounced "Waah").[19] This is the only definitive indigenous record of Eta Carinae's outburst identified in the literature to date.

In 2011, light echoes from the 19th century Great Eruption of η Carinae were detected using the U.S. National Optical Astronomy Observatory's Blanco 4-meter telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory. Analysis of the reflected spectra indicated the light was emitted when η Carinae was a 5000 K G2-to-G5 supergiant, some 2000 K cooler than other supernova imposter events.[20]

X-ray source

4U 1037–60 (A 1044–59) is Eta Carinae. Three structures around Eta Carinae are thought to represent shock waves produced by matter rushing away from the superstar at supersonic speeds. The temperature of the shock-heated gas ranges from 60 MK in the central regions to 3 MK on the horseshoe-shaped outer structure. "The Chandra image contains some puzzles for existing ideas of how a star can produce such hot and intense X-rays," says Prof. Kris Davidson of the University of Minnesota.[21]

A "spectroscopic minimum", or "X-ray eclipse", appeared in 2003. Astronomers organized a large observing campaign which included every available ground-based (e.g. CCD optical photometry[2]) and space observatory, including major observations with the Hubble Space Telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the INTEGRAL Gamma-ray space observatory, and the Very Large Telescope. Primary goals of these observations were to determine if, in fact, Eta Carinae is a binary star and, if so, to identify its companion star; to determine the physical mechanism behind the "spectroscopic minima"; and to understand their relation (if any) to the large-scale eruptions of the 19th century.

There is good agreement between the X-ray light curve and the evolution of a wind-wind collision zone of a binary system. These results were complemented by new tests on radio wavelengths.[22]

Spectrographic monitoring of Eta Carinae[23] showed that some emission lines faded every 5.52 years, and that this period was stable for decades. The star's radio emission,[24] along with its X-ray brightness,[25] also drop precipitously during these "events" as well. These variations, along with ultra-violet variations, suggest a high probability that Eta Carinae is actually a binary star in which a hot, lower-mass star revolves around η Carinae in a 5.52-year, highly eccentric elliptical orbit.[11]

The ionizing radiation emitted by the secondary star in Eta Carinae is the major radiation source of the system. Much of this radiation is absorbed by the primary stellar wind, mainly after it encounters the secondary wind and passes through a shock wave. The amount of absorption depends on the compression factor of the primary wind in the shock wave. The compression factor is limited by the magnetic pressure in the primary wind.[26] The variation of the absorption by the post-shock primary wind with orbital phase changes the ionization structure of the circumbinary gas, and can account for the radio light curve of Eta Carinae. Fast variations near periastron passage are attributed to the onset of the accretion phase.

Future prospects

Because of their disproportionately high luminosities, very large stars such as Eta Carinae use up their fuel very quickly. Eta Carinae is expected to explode as a supernova or hypernova some time within the next million years or so. As its current age and evolutionary path are uncertain, however, it could explode within the next several millennia or even in the next few years. LBVs such as Eta Carinae may be a stage in the evolution of the most massive stars; the prevailing theory now holds that they will exhibit extreme mass loss and become Wolf-Rayet stars before they go supernova, if they are unable to hold their mass to explode as a hypernova.[27]

More recently, another possible Eta Carinae analogue was observed: SN 2006jc, some 77 million light years away in UGC 4904, in the constellation of Lynx.[28] Its brightened appearance was noted on 20 October 2004, and was reported by amateur astronomer Koichi Itagaki as a supernova. However, although it had indeed exploded, hurling 0.01 solar masses (~20 Jupiters) of material into space, it had survived, before finally exploding nearly two years later as a Mag 13.8 type Ib supernova, seen on 9 October 2006. Its earlier brightening was a supernova impostor event.

The similarity between Eta Carinae and SN 2006jc has led Stefan Immler of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center to suggest that Eta Carinae could explode in our lifetime, or even in the next few years. However, Stanford Woosley of the University of California in Santa Cruz disagrees with Immler’s suggestion, and says it is likely that Eta Carinae is at an earlier stage of evolution, and that there are still several stages of nuclear burning to go before the star runs out of fuel.

In NGC 1260, a spiral galaxy in the constellation of Perseus some 238 million light years from earth, another analogue star explosion, supernova SN 2006gy, was observed on September 18, 2006. A number of astronomers modelling supernova events have suggested that the explosion mechanism for SN 2006gy may be very similar to the fate that awaits Eta Carinae.[citation needed]

This article or section appears to contradict itself. (January 2011) |

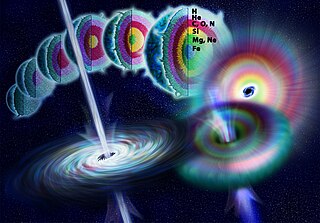

Drawing of a massive star collapsing to form a black hole. Energy released as jets along the axis of rotation forms the gamma ray bursts.

Credit: Nicolle Rager Fuller/NSF

It is possible that the Eta Carinae hypernova or supernova, when it occurs, could affect Earth, about 7,500 light years away. It is unlikely, however, to affect terrestrial lifeforms directly, as they will be protected from gamma rays by the atmosphere, and from some other cosmic rays by the magnetosphere. The damage would likely be restricted to the upper atmosphere, the ozone layer, spacecraft, including satellites, and any astronauts in space, although a certain few [1] claim that radiation damage to the upper atmosphere would have catastrophic effects as well. At least one scientist has claimed that when the star explodes, "it would be so bright that you would see it during the day, and you could even read a book by its light at night".[29] A supernova or hypernova produced by Eta Carinae would probably eject a gamma ray burst (GRB) out on both polar areas of its rotational axis. Calculations show that the deposited energy of such a GRB striking the Earth's atmosphere would be equivalent to one kiloton of TNT per square kilometer over the entire hemisphere facing the star with ionizing radiation depositing ten times the lethal whole body dose to the surface.[30] This catastrophic burst would probably not hit Earth, though, because the rotation axis does not currently point towards our solar system. If Eta Carinae is a binary system, this may affect the future intensity and orientation of the supernova explosion that it produces, depending on the circumstances.[11]

See also

- Homunculus Nebula

- LBV 1806-20

- Pistol Star

- SN 2006gy

- List of most luminous stars

- List of largest stars

- List of most massive stars

- Bipolar outflow

References

- ^ a b c d e "SIMBAD query result: V* eta Car – Variable Star". Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2008-04-25.—some of the data is located under "Measurements".

- ^ a b c

Fernández Lajús, Eduardo (Dec 19, 2011). "Optical monitoring of Eta Carinae". Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Retrieved 2011-12-26.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "GCVS Query=Eta+Car". General Catalogue of Variable Stars @ Sternberg Astronomical Institute, Moscow, Russia. Retrieved 2010-11-24.

- ^ "Eta Carinae: New View of Doomed Star". Chandra X-ray Center. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ^ "The HST Treasury Program on Eta Carinae". etacar.umn.edu. 2003-09-01. Retrieved 2011-12-26.

- ^ "VIZIER Details for Eta Carinae in Gould's Uranomatria Argentina". Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2011-02-14.

- ^ Davidson, Kris; Humphreys, Roberta (1997). "Eta Carinae and its Environment". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 35 (1): 1–32. Bibcode:1997ARA&A..35....1D. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.35.1.1.

- ^ Kostjuk N.D.: HD-DM-GC-HR-HIP-Bayer-Flamsteed Cross Index 2002, refer to "table3.dat", the name "Foramen" somehow originating from ref #24: Rak I.V., Kholshevnikov K.V., Atlas Zvezdnogo neba, Sankt-Peterburg, "Neva", 1995

- ^ Template:Zh icon AEEA (Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy) 天文教育資訊網 2006 年 7 月 28 日

- ^ Template:Zh icon 中國星座神話, written by 陳久金. Published by 台灣書房出版有限公司, 2005, ISBN 978-986-7332-25-7.

- ^ a b c Nancy Neal-Jones, Bill Steigerwald, "NASA Satellite Detects Massive Star Partner", NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, 1 November 2005

- ^

Frommert, Hartmut & Kronberg, Christine (February 2, 1998). "Peculiar star Eta Carinae, in Carina". Students for the Exploration and Development of Space (SEDS). Retrieved 2012-02-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stockdale, Christopher J.; Rupen, Michael P.; Cowan, John J.; Chu, You-Hua; Jones, Steven S. (2001). "The fading radio emission from SN 1961v: evidence for a Type II peculiar supernova?". The Astronomical Journal. 122 (1): 283. arXiv:astro-ph/0104235. Bibcode:2001AJ....122..283S. doi:10.1086/321136.

- ^ Robert Naeye, "Supernova Impostor Goes Supernova", NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, 4 April 2007

- ^ Shiga, D. (2007). "Star's odd double explosion hints at antimatter trigger". New Scientist. 2598 (2626): 18. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(07)62628-1.

- ^

see various articles in R.M. Humphreys & K.Z. Stanek (eds.) (2005). "The Fate of the Most Massive Stars". ASP Conference 332. Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

{{cite conference}}:|author=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Historical light curve". Retrieved 2011-12-26.

- ^ a b Courtland, Rachel. "'Supernova impostor' begins to dim unexpectedly", NewScientist news service, 7 August 2008

- ^ Hamacher, D. W.; Frew, D. J. (2010). "An Aboriginal Australian Record of the Great Eruption of Eta Carinae". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 13 (3): 220–234. arXiv:1010.4610. Bibcode:2010arXiv1010.4610H.

- ^

Rest, A. (2012-02-16). "Light echoes reveal an unexpectedly cool η Carinae during its nineteenth-century Great Eruption". Nature. 482 (7385): 375–378. doi:10.1038/nature10775. ISSN 0028-0836. Retrieved 2012-02-17.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Chandra Takes X-ray Image of Repeat Offender". Science News. NASA. 8 October 1999.

- ^

Falceta-Gonçalves, D.; Jatenco-Pereira, V.; Abraham, Z. (2005). "Wind-wind collision in the η Carinae binary system: a shell-like event near periastron". MNRAS. 357 (3): 895. arXiv:astro-ph/0404363. Bibcode:2005MNRAS.357..895F. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.08682.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Damineli, A. (1996). "The 5.52 Year Cycle of Eta Carinae". ApJ. 460 (1): L49. Bibcode:1996ApJ...460L..49D. doi:10.1086/309961.

- ^ Stephen White, "Radio outburst of Eta Carinae", Department of Astronomy, University of Maryland College Park

- ^ Michael Corcoran, "RXTE X-ray lightcurve", Goddard Space Flight Center, last updated 10 December 2008

- ^

Kashi, A.; Soker, N. (2007). "Modelling the Radio Light Curve of Eta Carinae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 378 (4): 1609. arXiv:astro-ph/0702389. Bibcode:2007astro.ph..2389K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.11908.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Smith, Nathan; Owocki, Stanley P. (2006). "On the Role of Continuum-driven Eruptions in the Evolution of Very Massive Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 645 (1): L45. arXiv:astro-ph/0606174. Bibcode:2006ApJ...645L..45S. doi:10.1086/506523.

- ^ Sanders, Robert (2007). "Massive star burps, then explodes". UC Berkeley News.

- ^ "Star dies in monstrous explosion", BBC News, 8 May 2007

- ^ Arnon Dar, A. De Rujula. "The threat to life from Eta Carinae and gamma ray bursts" Astrophysics and Gamma Ray Physics in Space, Series Vol. XXIV (2002), pp. 513–523

External links

- NASA image released Feb. 24, 2012

- Variable Star Of The Month AAVSO. April, 2000: Eta Carinae

- 'Eta Carinae — an evolved triple-star system?' by Wolfgang Kundt and Christoph Hillemanns

- HST Treasury Project and General Information on Eta Carinae

- Eta Carinae profile

- Is there a "clock" in Eta Carinae? – Brazilian research about the star

- Broad Band Optical Monitoring

- X-ray Monitoring by RXTE

- Possible Hypernova could affect Earth

- ESO press release about the possibility of a supernova in 10 to 20 millennia

- The 2003 Observing Campaign

- Davidson, Kris; et al. (1999). "An Unusual Brightening Of Eta Carinae". The Astronomical Journal. 118 (4). The Astronomical Journal: 1777. Bibcode:1999AJ....118.1777D. doi:10.1086/301063.

- Nathan, Smith (1998). "The Behemoth Eta Carinae: A Repeat Offender". Astronomical Society of the Pacific. Retrieved 2006-08-13.

- Eta Carinae at SIMBAD