Gun politics in the United States: Difference between revisions

Grahamboat (talk | contribs) |

→Gun laws: inidcate that this law was struck down by the SCOTUS |

||

| Line 366: | Line 366: | ||

'''Gun Free School Zones Act of 1995''' |

'''Gun Free School Zones Act of 1995''' |

||

[[Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990|The Federal Gun Free School Zone Act of 1995]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.leaa.org/index.html |title=Home |publisher=Leaa.org |date=2008-09-24 |accessdate=2010-11-21}}</ref> severely |

[[Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990|The Federal Gun Free School Zone Act of 1995]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.leaa.org/index.html |title=Home |publisher=Leaa.org |date=2008-09-24 |accessdate=2010-11-21}}</ref> severely limited where a person may legally carry a firearm, although this was voided by[[ United States v. Lopez]] as an abuse of the [[Commerce Clause]]. It did this by making it generally unlawful for an armed citizen to travel on any public sidewalk, road, or highway, that passes within one-thousand (1000) feet of the '''property-line''' of any K-12 school in the nation. This seems to severely restrict the ability of persons to carry firearms, especially in densely populated areas with many schools. Only if one has a state permit to carry a firearm are they exempt from the one-thousand foot rule, however they are still prohibited from carrying on school grounds. |

||

"(B) Subparagraph (A) does not apply to the possession of a |

"(B) Subparagraph (A) does not apply to the possession of a |

||

firearm— |

firearm— |

||

Revision as of 20:02, 6 March 2012

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

Template:Gun politics by country

Gun politics in the United States refers to an ongoing political and social debate regarding both the restriction and availability of firearms within the United States. It has long been among the most controversial and intractable issues in American politics.[1] For the last several decades, the debate has been characterized by a stalemate between an individual right to bear arms based on the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution and the responsibility of government to prevent crime, maintain order and protect the wellbeing of its citizens.[2][3] In District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008), the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Second Amendment protects the right of an individual to own a firearm for the purposes of self defense within the home, while at the same time reaffirming the constitutionality of a wide range of long standing gun control laws.[4] Repeated polling has found that a majority of Americans believe the constitution ensures their right to own a gun,[5][6] and a majority also supports stricter enforcement of current laws.[7] However, only 43 percent believe new laws would be more effective than better enforcement of existing laws in reducing gun violence in the United States.[7]

Gun culture

In his article, "America as a Gun Culture," historian Richard Hofstadter popularized the phrase gun culture to describe the long-held affections for firearms within America, many citizens embracing and celebrating the association of guns and America's heritage.[8] The right to own a gun and defend oneself is considered by some, especially those in the West and South,[9] as a central tenet of the American identity. This stems in part from the nation's frontier history, where guns were integral to westward expansion, enabling settlers to guard themselves from Native Americans, animals and foreign armies, frontier citizens often assuming responsibility for self-protection. The importance of guns also derives from the role of hunting in American culture, which remains popular as a sport in the country today.[10]

This viewpoint[clarification needed] has the least level of support in urban and industrialized regions.[10] Where a cultural tradition of conflating violence and gun ownership with the "redneck" stereotype has played a part in promoting the support of gun regulation.[11]

In 1995, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, whose employees routinely carry such weapons in the line of duty, estimated that the number of firearms available in the US was 223 million.[12] About 25% of the adults in the United States personally own a gun, the vast majority of them men.[13] About half of the adult U.S. population lived in households with guns.[14] Less than half of gun owners say that the primary reason they own a gun is for self-protection against crime, reflecting a popularity of hunting and sport-shooting among gun owners. As hunting and sport-shooting tends to favor rural areas, naturally the bulk of gun owners generally live in rural areas and small towns.[13] This attribute associates with low involvement in criminal violence, and therefore most guns are in the hands of people who are unlikely to misuse them and who tend to not have criminal records.[13]

Guns are prominent in contemporary U.S. popular culture as well, appearing frequently in movies, television, music, books, and magazines.[15]

Origins

The origins of American gun culture can be traced back to; the American Revolutionary War, hunting/sporting ethos and the militia/frontier ethos that draw from the country's early history.[3]

The American hunting/sporting passion comes from a time when the United States was an agrarian, subsistence nation where hunting was an auxiliary source of food for some settlers, and also a deterrence to animal predators. A connection between shooting skills and survival among rural American men was in many cases a 'rite of passage' for those entering manhood. Today, hunting survives as a central sentimental component of a gun culture as a way to control animal populations across the country, regardless of modern trends away from subsistence hunting and rural living.[3]

The militia/frontiersman spirit derives from an early American dependence on arms to protect themselves from hostile Native Americans and foreign armies. Survival depended upon everyone being capable of carrying a weapon. In the 18th century, there was neither budget nor manpower nor government desire to maintain a full time army, believing they were a threat to the rights of the civilian populace. Therefore, the armed citizen-soldier carried the responsibility. Service in militia, including providing his own ammunition and weapons, was mandatory for all men. Yet, as early as the 1790s, the mandatory universal militia duty gave way to voluntary militia units and a reliance on a regular army, with a decline of the importance of militia trend continuing throughout the 19th century.[3]

Closely related to the militia tradition was the frontier tradition, with the Nineteenth Century westward expansion closely associated with firearms. Regardless, today, there remains a powerful central elevation of the gun associated with the hunting/sporting and militia/frontier ethos among the American Gun Culture.[3] Though it has not been a necessary part of daily survival for a long time, generations of Americans have continued to embrace and glorify it as a living inheritance—a permanent element of the nation's style and culture.[16]

Popular culture

The gun has long been a symbol of power and masculinity.[17] In popular literature, frontier adventure was most famously told by James Fenimore Cooper, who is credited by Petri Liukkonen with creating the archetype of an 18th-century frontiersman through such novels as "The Last of the Mohicans" (1826) and "The Deerslayer" (1840).[18]

In the late 19th century, cowboy and Wild West imagery entered the collective imagination. The first American female superstar, Annie Oakley, was a sharpshooter who toured the country starting in 1885, performing in Buffalo Bill's Wild West show. The cowboy archetype of individualist hero was established largely by Owen Wister in stories and novels, most notably "The Virginian" (1902), following close on the heels of Theodore Roosevelt's "The Winning of the West" (1889–1895), a history of the early frontier.[19][20][21] Cowboys were also popularized in turn of the 20th century cinema, notably through such early classics as "The Great Train Robbery" (1903) and "A California Hold Up" (1906)--the most commercially successful film of the pre-nickelodeon era.[22]

Gangster films began appearing as early as 1910, but became popular only with the advent of sound in film in the 1930s. The genre was boosted by the events of the prohibition era, such as bootlegging and the St. Valentine's Day Massacre of 1929, the existence of real-life gangsters (e.g., Al Capone) and the rise of contemporary organized crime and escalation of urban violence. These movies flaunted the archetypal exploits of "swaggering, cruel, wily, tough, and law-defying bootleggers and urban gangsters".[23]

With the arrival of World War II, Hollywood produced many morale boosting movies, patriotic rallying cries that affirmed a sense of national purpose. The image of the lone cowboy was replaced in these combat films by stories that emphasized group efforts and the value of individual sacrifices for a larger cause, often featuring a group of men from diverse ethnic backgrounds who were thrown together, tested on the battlefield, and molded into a dedicated fighting unit.[24]

Guns frequently accompanied famous heroes and villains in late 20th century American films, from the outlaws of Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and The Godfather (1972), to the fictitious law and order avengers like Dirty Harry (1971) and RoboCop (1987). In the 1970s, films portrayed fictitious and exaggerated characters, madmen ostensibly produced by the Vietnam war in films like Taxi Driver (1976) and Apocalypse Now (1979), while other films told stories of fictitious veterans who were supposedly victims of the war and in need of rehabilitation (Coming Home and The Deer Hunter, both 1978).[25] Many action films continue to celebrate the gun toting hero in fantastical settings. At the same time, the negative role of the gun in fictionalized modern urban violence has been explored in films like Boyz n the Hood (1991) and Menace 2 Society (1993).

History

Revolutionary War

In the years prior to the Revolutionary War, the British, in response to the colonists' unhappiness over increasingly direct control and taxation of the colonies, imposed a powder embargo on the colonies in an attempt to lessen the ability of the colonists to resist British encroachments into what the colonies regarded as local matters. Two direct attempts to disarm the colonial militias fanned what had been a smoldering resentment of British interference into the fires of war. These two incidents were the attempt to confiscate the cannon of the Concord and Lexington militias, leading to the Battles of Lexington and Concord of April 19, 1775, and the attempt, on April 20, to confiscation militia powder stores in the armory of Williamsburg, Virginia, which led to the Gunpowder Incident and a face off between Patrick Henry and hundreds of militia members on one side and the Royal Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, and British seamen on the other. The Gunpowder Incident was eventually settled by paying the colonists for the powder.[26]

Minutemen were members of teams of select men from the American colonial militia during the American Revolutionary War who vowed to be ready for battle against the British within one minute of receiving notice[citation needed]. On the night of April 18/April 19, 1775, minuteman Paul Revere, William Dawes, and Dr. Samuel Prescott spread the news that "the Red Coats are coming,".[citation needed] Paul Revere was captured before completing his mission when the British marched towards the arsenal in Lexington and Concord to collect the patriots' weapons. Only Dr. Prescott was able to complete the journey to Concord.[27] The right to firearms was thus an issue in America from the very beginning.

Jacksonian era

The Jacksonian Era lasted roughly from President Andrew Jackson's 1828 election until the slavery issue became dominant after 1850. French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville traveled in America early during this era, and according to Tocqueville, a distinguishing characteristic of American society in the 1830s, the era of Jacksonian democracy, was "a pervasive spirit of individualism". The French commentator confessed that individualism was a novel term coined to capture a new idea."[28] During this same period, some of the first gun control laws were passed in the United States, and, as a result, the Individual Right interpretation of the Second Amendment began and grew in direct response to these early gun control laws, in keeping with this new "pervasive spirit of individualism".[29] As noted by Cornell, "Ironically, the first gun control movement helped give birth to the first self-conscious gun rights ideology built around a constitutional right of individual self-defense."[29]

The Individual Right interpretation of the Second Amendment first arose in Bliss v. Commonwealth (1822, KY),[30] which evaluated the right to bear arms in defense of themselves and the state pursuant to Section 28 of the Second Constitution of Kentucky (1799). The right to bear arms in defense of themselves and the state was interpreted as an individual right, for the case of a concealed sword cane. This case has been described as about “a statute prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons [that] was violative of the Second Amendment””.[31] As noted in the Northern Kentucky Law Review Second Amendment Symposium: Rights in Conflict in the 1980’s, vol. 10, no. 1, 1982, p. 155, "The first state court decision resulting from the "right to bear arms" issue was Bliss v. Commonwealth. The court held that "the right of citizens to bear arms in defense of themselves and the State must be preserved entire, ..."" "This holding was unique because it stated that the right to bear arms is absolute and unqualified."[32][33]

Also during the Jacksonian Era, the first Collective Right interpretation of the Second Amendment arose. In State v. Buzzard (1842, Ark), the Arkansas high court adopted a militia-based, political right, reading of the right to bear arms under state law, and upheld the 21st section of the second article of the Arkansas Constitution that declared, "that the free white men of this State shall have a right to keep and bear arms for their common defense",[34] while rejecting a challenge to a statute prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons. The Arkansas high court declared "That the words "a well regulated militia being necessary for the security of a free State", and the words "common defense" clearly show the true intent and meaning of these Constitutions [i.e., Ark. and U.S.] and prove that it is a political and not an individual right, and, of course, that the State, in her legislative capacity, has the right to regulate and control it: This being the case, then the people, neither individually nor collectively, have the right to keep and bear arms." Joel Prentiss Bishop’s influential Commentaries on the Law of Statutory Crimes (1873) took Buzzard's militia-based interpretation, a view that Bishop characterized as the “Arkansas doctrine", as the orthodox view of the right to bear arms in American law.[34][35]

The two early state court cases, Bliss and Buzzard, set the fundamental dichotomy in interpreting the Second Amendment, i.e. whether it secured an Individual Right versus a Collective Right. A debate about how to interpret the Second Amendment evolved through the decades and remained unresolved until the 2008 District of Columbia v. Heller U.S. Supreme Court decision.

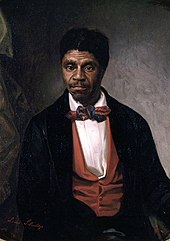

Antebellum era

One of the early political battles over the right to firearms involved the rights of slaves to carry firearms in the United States; the battle over the rights of slaves resulted in political battles, in the aftermath of the 1856 Supreme Court decision Dred Scott v. Sandford that denied Negroes the full rights of citizenship.[36][37] In Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1856) (the "Dred Scott Decision"), the Supreme Court indicated that: "It would give to persons of the negro race, who were recognized as citizens in any one State of the Union ... the full liberty ... to keep and carry arms wherever they went."

The Dred Scott Decision contains additional significant wording:

More especially, it cannot be believed that the large slaveholding States regarded them as included in the word citizens, or would have consented to a Constitution which might compel them to receive them in that character from another State. For if they were so received, and entitled to the privileges and immunities of citizens, it would exempt them from the operation of the special laws and from the police regulations which they considered to be necessary for their own safety. It would give to persons of the negro race, who were recognized as citizens in any one State of the Union, the right to enter every other State whenever they pleased, singly or in companies, without pass or passport, and without obstruction, to sojourn there as long as they pleased, to go where they pleased at every hour of the day or night without molestation, unless they committed some violation of law for which a white man would be punished; and it would give them the full liberty of speech in public and in private upon all subjects upon which its own citizens might speak; to hold public meetings upon political affairs, and to keep and carry arms wherever they went [emphasis added].

Reconstruction era

With the Civil War ending, the question of the rights of freed slaves to carry arms and to belong to militia came to the attention of the Federal courts. In response to the problems freed slaves faced in the Southern states, the Fourteenth Amendment was drafted.

When the Fourteenth Amendment was drafted, Representative John A. Bingham of Ohio used the Court's own phrase "privileges and immunities of citizens" to include the first Eight Amendments of the Bill of Rights under its protection and guard these rights against state legislation.[38]

The debate in the Congress on the Fourteenth Amendment after the Civil War also concentrated on what the Southern States were doing to harm the newly freed slaves. One particular concern was the disarming of former slaves.

The Second Amendment attracted serious judicial attention with the Reconstruction era case of United States v. Cruikshank which ruled that the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment did not cause the Bill of Rights, including the Second Amendment, to limit the powers of the State governments, stating that the Second Amendment "has no other effect than to restrict the powers of the national government."

Akhil Reed Amar notes in the Yale Law Journal, the basis of Common Law for the first ten amendments of the U.S. Constitution, which would include the Second Amendment, "following John Randolph Tucker's famous oral argument in the 1887 Chicago anarchist Haymarket Riot case, Spies v. Illinois":

Though originally the first ten Amendments were adopted as limitations on Federal power, yet in so far as they secure and recognize fundamental rights—common law rights—of the man, they make them privileges and immunities of the man as citizen of the United States...[39]

20th century

A famous and widely publicized case where fully automatic weapons were used in crime in the United States was during the Saint Valentine's Day massacre during the winter of 1929; this Prohibition-era gangster sub-machine gun mass murder led directly to the National Firearms Act of 1934, which was passed over a year after Prohibition had ended. Since 1934, fully automatic weapons have been heavily regulated by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF), but ones manufactured before May 19, 1986 are available to citizens who are not otherwise prohibited, in those states that do not prohibit them, upon paying a $200 transfer tax, submission of a full set of fingerprints on FBI Form FD-258, certification provided by the local chief of police, sheriff of the county, head of the State police, or State or local district attorney or prosecutor, and approval by the BATF.[40][41] Other crimes involving fully automatic weapons in the United States have not been as widely publicized since.[42] However, the lesser known 1997 North Hollywood shootout involved two men carrying illegally imported automatic AKMs.[43]

In the latter half of the 20th Century, groups such as the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the Gun Owners of America (GOA) organized voters and campaign volunteers to focus citizen communication and interest when anti-gun rights legislation was under consideration, both at federal and state levels.

The United States was generally seen as having the least stringent anti-gun rights laws in the developed world, with the possible exception of Switzerland, in part due to the strength of the gun lobby, particularly the NRA.[44] The NRA historically supported gun laws intended to prevent criminals from obtaining firearms, while opposing new restrictions that affected law-abiding citizens[citation needed].

An important electoral showdown over gun control came in 1970, when Senator Joseph Tydings (D, MD), who had highlighted crime in the District of Columbia and sponsored the Firearms Registration and Licensing Act, was defeated for reelection.

The GOA grew out of dissatisfaction with the NRA, and historically rejected any gun laws that infringed the rights of law-abiding citizens, putting it at odds with the NRA on many legislative issues.

Besides the GOA, other national gun rights groups often took a stronger stance than the NRA. These groups criticize the NRA's history of support for some gun control legislation, such as the Gun Control Act of 1968, the ban on armor-piercing projectiles, point-of-purchase background checks (NICS). Some of these groups are The Second Amendment Sisters, Second Amendment Foundation, and Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership. These groups, like the GOA, believe any compromise leads to incrementally greater restrictions.[45][46]

Handgun Control Inc. (HCI), founded in 1974 by businessman Pete Shields, formed a partnership with the National Coalition to Ban Handguns (NCBH), also founded in 1974. Soon parting ways, the NCBH was renamed the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence in 1990, and while smaller than HCI, generally took a tougher stand on gun regulation than HCI.[47]

HCI saw an increase of interest and fund raising in the wake of the 1980 murder of John Lennon. By 1981 membership exceeded 100,000. Measured in dollars contributed to congressional campaigns, HCI contributed $75,000. Following the 1981 assassination attempt on President Reagan, and the resultant injury of James Brady, Sarah Brady joined the board of HCI in 1985. HCI was renamed in 2001 to Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.[48]

In the 1990s, gun politics took a turn to the right in response to two high profile ATF incidents, Ruby Ridge and Waco, that led to mobilization of modern militia groups.[49] These incidents combined with the passage of the Brady Act in 1993 and the Assault Weapons Ban a year later increased the fears of those who felt the Federal Government would confiscate their firearms.[47][50] The Militia Movement expanded throughout the 1990s.

21st century

One of the first major victories for gun rights advocates at the federal level came in 2004, when the Assault Weapons Ban was scheduled to expire by its own terms. Efforts by gun control advocates to extend the ban at the federal level failed; two later attempts to reestablish the ban also failed.

The NRA opposed bans on handguns in Washington D.C. and San Francisco, while also supporting the 2007 NICS Improvement Amendments Act (H.R. 2640), which strengthened requirements for background checks for firearm purchases.[51]

The GOA especially took issue with the NRA over a portion of the 2007 "The School Safety And Law Enforcement Improvement Act" known as The NICS Improvement Amendments Act, which they termed the "Veteran's Disarmament Act".[52]

Besides the GOA, other national gun rights groups continue to take a stronger stance than the NRA. Groups such as The Second Amendment Sisters, Second Amendment Foundation, Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership, and the Pink Pistols continue much as they did in the late 20th Century, but new groups have also arisen, such as the Students for Concealed Carry, which grew largely out of perceived safety-issues resulting from the creation of 'Gun-free' zones that were legislatively mandated at many schools, amidst a response to widely publicized school shootings. Even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pitched in, with an extensive study on gun control[53] which found "Evidence was insufficient to determine the effectiveness of any of these laws." A similar survey of firearms research by the United States National Academy of Sciences arrived at nearly identical conclusions in 2004.[54]

In District of Columbia v. Heller, No. 07-290, the United States Supreme Court held that Americans have an individual right described in the Second Amendment to possess firearms "for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense within the home". It is an appeal from Parker v. District of Columbia, 478 F.3d 370 (D.C. Cir. 2007), a decision in which the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit became the first federal appeals court in the United States to rule that a firearm ban infringes the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution, and the second to expressly interpret the Second Amendment as protecting an individual right to possess firearms for private use. The first federal case that interpreted the Second Amendment as protecting an individual right was United States v. Emerson, 270 F.3d 203 (5th Cir. 2001).[55]

According to The Center for Public Integrity, 145 groups are registered as making gun-related filings to lobby Congress, the largest being the National Rifle Association, spending about $1.5 million per year, predominantly through two lobbying firms, the WPP Group and The Federalist Group.[56] Ranked by total filings, gun-rights lobbying exceeded gun-control lobbying by the ratio of approximately 3:1.[57]

Measured in dollars, in 2007, gun rights political spending on lobbying totaled $1,959,407 versus gun control spending of $60,800.[58] The NRA is the largest gun rights lobbying organization in the United States.

Regional and partisan divides

Regional differences tend to be greater than partisan ones for gun politics in the United States. Jurisdictions that favor gun control are concentrated in parts of the Northeastern United States such as New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, the District of Columbia, and Maryland, but also include States with major metropolitan areas, notably California and Illinois. The Northwest, such as Montana, Idaho and Washington; the Deep South, including Alabama, Georgia and Florida; and the Southwest, such as Texas, New Mexico, and Utah tend to support gun rights. Other areas, including the Midwest and Plains States, are mixed.[59] Alaska, Arizona and Vermont do not require any license in order to carry concealed weapons in public places, but there are laws in these states prohibiting concealed weapons in certain places (e.g., in Alaska it is not permitted to carry a weapon, concealed or otherwise, into a bar or tavern).[60] The spread of concealed carry laws since 1986 in those states that tend to be in support of gun rights has led to the widespread, legally permitted, carrying of concealed handguns by civilians in many parts of the United States. Opinions on gun control can vary within a jurisdiction. In general, large urban jurisdictions tend to favor gun control to reduce crime, while rural populations and small towns oppose it for much the same reason.

Though gun control is not strictly a partisan issue, there is generally more support for gun control legislation in the Democratic Party than in the Republican Party.[61] The Libertarian Party, whose campaign platforms favor classical liberal (i.e. limited) government and individual rights, is outspokenly against gun control, and this stance is more ideological than the stance of the Republican Party, which represents people who tend to oppose gun regulations.

Types of firearms

Political Scientist Earl Kruschke has described how, in the gun control debate, firearms have been viewed in only three general classes by gun control advocates: 1) long guns 2) hand guns and 3) automatic and semi-automatic weapons. The first category has generally been associated with sporting and hunting uses; the second category, handguns, describe weapons which can be held with one hand such as pistols and revolvers; and the third general category has been most commonly associated in public political perception with military uses. Notably the AR-15 and AK-47 style firearms have contributed to this perception.

If sometimes confused in public debate, the two firearm types in the third general category are functionally and legally distinct. Fully automatic firearms of any kind (including military assault rifles) have been subject to requirements for registration by owners and licensing of dealers since the passage of the National Firearms Act in 1934. Further import restrictions were part of the Gun Control Act of 1968, and the transfer of newly manufactured machine-guns to private citizens was banned with passage of the Firearm Owners Protection Act in 1986. New machine-guns in the US are still legal for purchase by the military and by governmental agencies, including civilian law enforcement; pre-1986 registered machine-guns are available to private citizens with federal registration (where permitted by state law), and have reached high market prices, eagerly sought by collectors because of their relative scarcity. An expansion has occurred in the number of states where such automatic weapons may legally be owned; for example, automatic-weapons were recently legalized in Kansas, subject only to federal NFA regulations.[62]

Many semi-automatic versions of military assault rifles—and the larger 20- or 30-round magazines they typically use—are again available for purchase by private citizens in the US (except where prohibited by state or municipal bans) since the "sunsetting" of the 1994 Federal Assault Weapons Ban on September 14, 2004. Some continue to be banned due to a 1989 amending of the Gun Control Act, which made some foreign-made firearms illegal for importation. However, firearms similar to those affected by the importation ban can now be manufactured domestically.[63][64]

In general terms, gun control advocates have paid little concern to the long guns used for sporting purpose as long guns are generally not viewed as associated with violent crime or suicide. For example, in 2005, 75% of the 10,100 homicides committed using firearms in the United States were committed using handguns, compared to 4% with rifles, 5% with shotguns, and the rest with type of firearm not specified.[65] Non-criminal homicides (i.e., acts of self-defense) and criminal homicides were counted together simply as homicides in these data.[65]

Kruschke describes incidents where public political perceptions have been shaped by a few high profile violent crimes associated with automatic and semi-automatic weapons, resulting in a relatively small percentage of the crime in absolute numbers, none-the-less have brought public focus on that type of weapon.[66]

Kruschke states, however, regarding the fully automatic firearms owned by private citizens in the United States, that "approximately 175,000 automatic firearms have been licensed by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (the federal agency responsible for administration of the law) and evidence suggests that none of these weapons has ever been used to commit a violent crime."[67]

Likewise, Kruschke states that automatic weapons are different than common semi-automatic hunting weapons, as the "most common examples [of automatic weapons] are machine guns, submachine guns, and certain types of military and police rifles".[68] This recognizes that there are semi-automatic household guns that are in widespread use like the .22 caliber Marlin Model 60 hunting rifle. Similarly, although Kruschke claims long guns are not being used in suicide, there are in fact instances of long guns that are used for suicides.[69]

Pro-gun groups claim that confusing voters about different types of guns continues to be a strategy of gun-control groups, who in turn claim that certain types of firearms are either particularly unsafe, particularly likely to be used in crime, or particularly unsuited for "sporting purposes," and therefore should be banned. The types of guns so designated has included: any small, inexpensive handgun ("junk gun" or "Saturday night special"[70]), any handgun weighing more than 50 ounces,[citation needed] any handgun not incorporating either new "smart-gun"[71] or "micro-stamping"[72] abilities, all handguns,[73] semi-automatic "assault weapons" (using either the 1994 definition[74] or a more expansive definition[75]), and .50 caliber rifles.[76]

The current bid to ban .50 caliber rifles nationally shows the typical issues that arise in campaigns to ban certain firearm types. Pro-ban groups have preferred the phrase "Sniper Rifle Ban" to promote the law, even though the .50 caliber rifles are typically considered "counter-sniper" and "anti-matériel" weapons. In fact, the term "sniper rifle" implies a much broader range of rifles:[77] the US M24 and M40 military sniper rifles are bolt-action, 7.62 mm caliber weapons with telescopic sights (both models being variants of the civilian Remington Model 700); the "D.C. Snipers" used a .223 semi-automatic rifle; and Charles Whitman, the 1966 "Texas Tower Sniper," used a common scoped hunting rifle (as did many of the private citizens who returned fire that day). Pro-gun groups see the attempts to ban .50-cal rifles as the first step toward banning an ever-expanding "sniper gun" or "high-powered rifle" category.[78] In promoting a California .50 caliber ban, the LAPD received criticism for deceiving the public when a police-owned Barrett M82 was produced for a press conference supporting the ban, while never mentioning that the rifle was already banned by existing state law.[79]

Political arguments

Political arguments of gun politics in the United States center around disagreements that range from the practical– does gun ownership cause or prevent crime?– to the constitutional– how should the Second Amendment be interpreted?– to the ethical– what should the balance be between an individual's right of self-defense through gun ownership and the People's interest in maintaining public safety? Political arguments about gun rights fall into two basic categories, first, does the government have the authority to regulate guns, and second, if it does, is it effective public policy to regulate guns.[48]

The first category, collectively known as rights-based arguments, consist of Second Amendment arguments, state constitution arguments, right of self-defense arguments, and security against tyranny and invasion arguments. Public policy arguments, the second category of arguments, revolve around the importance of a militia, the reduction of gun violence and firearm deaths, and also can include arguments regarding security against foreign invasions.

Courts and the law

Supreme Court decisions

Since the late 19th century, with three key cases from the pre-incorporation era, the Supreme Court consistently ruled that the Second Amendment (and the Bill of Rights) restricts only the federal Congress, and not the States, in the regulation of guns.[80] Scholars predicted that the Court's incorporation of other rights suggests that they may incorporate the Second, should a suitable case come before them.[81]

"Americans also have a right to defend their homes, and we need not challenge that. Nor does anyone seriously question that the Constitution protects the right of hunters to own and keep sporting guns for hunting game any more than anyone would challenge the right to own and keep fishing rods and other equipment for fishing– or to own automobiles. To "keep and bear arms" for hunting today is essentially a recreational activity and not an imperative of survival, as it was 200 years ago. "Saturday night specials" and machine guns are not recreational weapons and surely are as much in need of regulation as motor vehicles." — Ex-Chief Justice Warren Burger, 1990.[82]

Until recently, there had been only one modern Supreme Court case that dealt directly with the Second Amendment, United States v. Miller.[83] In that case, the Supreme Court did not address the incorporation issue, but the case instead hinged on whether a sawed-off shotgun "has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia."[81] In quashing the indictment against Miller, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas stated that the National Firearms Act of 1934, "offend[ed] the inhibition of the Second Amendment to the Constitution." The federal government then appealed directly to the US Supreme Court. On appeal the federal government did not object to Miller's release since he had died by then, seeking only to have the trial judge's ruling on the unconstitutionality of the federal law overturned. Under these circumstances, neither Miller nor his attorney appeared before the US Supreme Court to argue the case. The Court only heard argument from the federal prosecutor. In its ruling, the Supreme Court overturned the trial court and upheld the law. For a more complete reading of this case, see Reynolds, Glenn Harlan and Denning, Brannon P., "Telling Miller's Tale" . 65 Law & Contemp. Probs. 113 (Spring 2002).[84]

District of Columbia v. Heller

On June 26, 2008, in District of Columbia v. Heller,[85] the United States Supreme Court affirmed, by a 5-4 vote, the decision of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals.[86] This decision struck down the D.C. gun law. It also clarifies the scope of the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution, stating that it stipulates an individual right irrespective of membership in a militia. However, the court made it clear that like other rights, the right to bear arms is not without limitations, leaving open the prospect of governmental regulation. The decision declined to rule on the incorporation of the Second Amendment, leaving its applicability to the states unsettled ("While the status of the Second Amendment within the twentieth-century incorporation debate is a matter of importance for the many challenges to state gun control laws, it is an issue that we need not decide."[87]).

McDonald v. Chicago

June 28, 2010, Chicago gun control law struck down 5 to 4. "The Fourteenth Amendment makes the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms fully applicable to the States."

Gun laws

Gun control laws and regulations exist at all levels of government, with the vast majority being local codes which vary between jurisdictions. The NRA reports 20,000 gun laws nationwide.[88] A study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine notes 300 federal and state laws regarding the manufacture, design, sale, purchase, or possession of guns.[89]

At the federal level, fully automatic weapons and short barrel shotguns have been taxed and mandated to be registered since 1934 with the National Firearms Act. The Gun Control Act of 1968 adds prohibition of mail-order sales and prohibits transfers to minors. The 1968 Act requires that guns carry serial numbers and implemented a tracking system to determine the purchaser of a gun whose make, model, and serial number are known. It also prohibited gun ownership by convicted felons and certain other individuals. The Act was updated in the 1990s with the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, mainly to add a mechanism for the criminal history of gun purchasers to be checked at the point of sale, and in 1996 with the Domestic Violence Offender Gun Ban to prohibit ownership and use of guns by individuals convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence.

The 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act enacted the now-defunct Federal Assault Weapons Ban, which banned the purchase, sale, or transfer of any weapon specifically named in the act, other weapons with a certain number of "defining features", and detachable magazines capable of holding more than 10 rounds of ammunition, that had been manufactured after the beginning date of the ban. The Assault Weapons Ban expired in 2004, but H.R. 6257 introduced June 12, 2008 sought to re-instate the ban indefinitely as well as to expand the list of banned weapons. The bill ultimately died in committee. New York, California, Massachusetts, Hawaii, Connecticut, and New Jersey and several municipalities have codified some provisions of the expired Federal ban into State and local laws.

Gun Free School Zones Act of 1995

The Federal Gun Free School Zone Act of 1995[90] severely limited where a person may legally carry a firearm, although this was voided byUnited States v. Lopez as an abuse of the Commerce Clause. It did this by making it generally unlawful for an armed citizen to travel on any public sidewalk, road, or highway, that passes within one-thousand (1000) feet of the property-line of any K-12 school in the nation. This seems to severely restrict the ability of persons to carry firearms, especially in densely populated areas with many schools. Only if one has a state permit to carry a firearm are they exempt from the one-thousand foot rule, however they are still prohibited from carrying on school grounds. "(B) Subparagraph (A) does not apply to the possession of a firearm— ...(ii) if the individual possessing the firearm is licensed to do so by the State in which the school zone is located"

See also

- Carrying concealed weapon

- Civilian Marksmanship Program

- Coalition to Stop Gun Violence

- Firearm case law in the United States

- Gun

- Gun laws in the United States (by state)

- Gun law in the United States

- Gun Owners of America (GOA)

- Gun politics

- Gun violence in the United States

- Gun violence

- Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership (JPFO)

- Joyce Foundation

- Mayors Against Illegal Guns Coalition

- National Rifle Association of America (NRA)

- Pink Pistols

- Proposition H (Failed San Francisco gun ban)

- Right to arms

- Second Amendment Foundation (SAF)

- Second Amendment Sisters

- Second Amendment to the United States Constitution

- Students for Concealed Carry on Campus

References

- ^ Wilcox, Clyde; Bruce, John W. (1998). The changing politics of gun control. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 1–4. ISBN 0847686140.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wilcox, Clyde; Bruce, John W. (1998). The changing politics of gun control. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 4. ISBN 0-8476-8615-9.

For many years a feature of this policy arena has been an insurmountable deadlock between a well-organized outspoken minority and a seemingly ambivalent majority

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Spitzer, Robert J.: The Politics of Gun Control, Chapter 1. Chatham House Publishers, 1995.

- ^ "Shooting Blanks - The Daily Beast". Retrieved 2010-03-23.

Justice Kennedy noted that, even where state and local governments were bound by the Bill of Rights, lawmakers "have substantial latitude and ample authority to impose reasonable regulations." Justice Scalia said that his Heller opinion "was very careful not to impose" severe limitations on gun control "precisely because it realized that" gun violence "is a national problem."

- ^ Wright, James D.: Public Opinion and Gun Control: A Comparison of Results from Two Recent National Surveys. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 455. (May 1981)

- ^ "Majority in U.S. poll support gun ownership rights - CNN.com". 2007-12-16. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ^ a b "Gun Poll: Men, women differ widely in gun control poll". Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ^ Hofstadter, Richard. "America as a Gun Culture." American Heritage Magazine, October 1970.

- ^ "Gun Ownership by State". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b "A look inside America's gun culture". ABC News Online. 2007-04-17. Archived from the original on Jun 02, 2008Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ William B. Bankston, Carol Y. Thompson, Quentin A. L. Jenkins, Craig J. Forsyth (1990) The Influence of Fear of Crime, Gender, and Southern Culture on Carrying Firearms for Protection. The Sociological Quarterly 31 (2) , 287–305

- ^ "Bureau of Justice Statistics Selected Findings" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-14. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ^ a b c Cook, Philip J.; Ludwig, Jens (2003). Evaluating gun policy: effects on crime and violence. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. pp. s. 3, 4. ISBN 0-8157-5311-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ""Gun Control", Just the Facts, 2005-12-30 (revised)". Justfacts.com. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ Dunbar, John (2007-02-16). "Report Urges FCC to Regulate TV Violence". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ^ JERVIS ANDERSON, GUNS IN AMERICA 10 (1984), page 21

- ^ Sidel, Victor W.; Wendy Cukier (2005). The Global Gun Epidemic: From Saturday Night Specials to AK-47s. Praeger Security International General Interest-Cloth. p. 130. ISBN 0-275-98256-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851)". Kirjasto.sci.fi. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ "American Literature: Prose, MSN Encarta". Archived from the original on 2009-10-31Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "New Perspectives on the West: Theodore Roosevelt, PBS, 2001". Pbs.org. 1919-01-06. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ ""Owen Wister (1860-1938)", Petri Liukkonen, Authors' Calendar, 2002". Kirjasto.sci.fi. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ ""Western Films", Tim Dirks, Filmsite, 1996-2007". Filmsite.org. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ ""Crime and Gangster Films", Tim Dirks, Filmsite, 1996-2007". Filmsite.org. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ Digital History, Steven Mintz. "Hollywood as History: Wartime Hollywood, Digital History". Digitalhistory.uh.edu. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ Digital History, Steven Mintz. "Hollywood as History: The "New" Hollywood, Digital History". Digitalhistory.uh.edu. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ "The Seizure Williamsburg, Va. Powder Magazine - April 21, 1775". Revwar75.com. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ Wills, Garry (1999). A Necessary Evil: A History of American Distrust of Government, Page 33. New York, NY; Simon & Schuster

- ^ Cornell, Saul (2006). A WELL-REGULATED MILITIA– The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-19-514786-5.

- ^ a b Cornell, Saul (2006). A WELL-REGULATED MILITIA– The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-19-514786-5.

- ^ Bliss v. Commonwealth, 2 Littell 90 (KY 1882).

- ^ United States. Anti-Crime Program. Hearings Before Ninetieth Congress, First Session. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off, 1967, p. 246.

- ^ Pierce, Darell R. (1982). "Second Amendment Survey". Northern Kentucky Law Review Second Amendment Symposium: Rights in Conflict in the 1980's. 10 (1): 155.

- ^ Two states, Alaska and Vermont, do not require a permit or license for carrying a concealed weapon to this day, following Kentucky's original position.

- ^ a b State v. Buzzard, 4 Ark. (2 Pike) 18 (1842).

- ^ Cornell, Saul (2006). A WELL-REGULATED MILITIA– The Founding Fathers and the Origins of Gun Control in America. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-19-514786-5.

"Dillon endorsed Bishop's view that Buzzard's "Arkansas doctrine," not the libertarian views exhibited in Bliss, captured the dominant strain of American legal thinking on this question."

- ^ Fehrenbacher, Don Edward. The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics. Oxford University Press: 2001. ISBN 0-19-514588-7.

- ^ The United States Supreme Court, Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney, "The Case of Dred Scott in the United States Supreme Court"

- ^ Kerrigan, Robert (June 2006). "The Second Amendment and related Fourteenth Amendment" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Amar, Akhil Reed (April 1992). "The Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment". Yale Law Journal: 1193.

- ^ "Firearms frequently asked questions". Retrieved 2008-04-24. [dead link]

- ^ "Firearms frequently asked questions". Retrieved 2008-04-24. [dead link]

- ^ Boston T. Party (Kenneth W. Royce) (1998). Boston on Guns & Courage. Javelin Press. pp. 3:15.

- ^ "Botched L.A. bank heist turns into bloody shootout". CNN. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ Thomas, David C. (2000). Canada and the United States: Differences that Count, Second Edition. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press. p. 71. ISBN 1-55111-252-3.

- ^ Singh, Robert P. (2003). Governing America: the politics of a divided democracy. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. p. 368. ISBN 0-19-925049-9.

- ^ Daynes, Byron W.; Tatalovich, Raymond (2005). Moral controversies in American politics. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. p. 172. ISBN 0765614200.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Wilcox, Clyde; Bruce, John W. (1998). The changing politics of gun control. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 183. ISBN 0-8476-8615-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "isbn0-8476-8615-9" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Spitzer, Robert J.: The Politics of Gun Control. Chatham House Publishers, Inc., 1995

- ^ Crothers, Lane (2003). Rage on the right: the American militia movement from Ruby Ridge to homeland security. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 97. ISBN 0742525465.

- ^ Snow, Robert J. (2002). Terrorists among us: the militia threat. Cambridge, Mass: Perseus. pp. s 85, 173. ISBN 0-7382-0766-7.

- ^ "Congress Passes Bill to Stop Mentally Ill From Getting Guns", Washington Post, December 20, 2007 "Congress yesterday approved legislation that would help states more quickly and accurately identify potential firearms buyers with mental health problems that disqualify them from gun ownership under federal law.... The NRA supports the bill..."

- ^ "Gun owners get stabbed in back". World Net Daily. December 23, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ^ "First Reports Evaluating the Effectiveness of Strategies for Preventing Violence: Firearms Laws". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 3, 2003. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ^ Firearms and Violence: A Critical Review, National Research Council, National Academy Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-309-09124-4

- ^ For more information concerning District of Columbia v Heller, please refer to the District of Columbia v. Heller page.

- ^ USA. "The Center for Public Integrity, National Rifle Association lobbying history". Publicintegrity.org. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ USA. "The Center for Public Integrity, Guns, Ammunition & Firearms lobbying history". Publicintegrity.org. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ The Center for Responsive Politics, Annual Lobbying on Ideology/Single-Issue database.

- ^ A look inside America's gun culture, ABC News Online, 2007-04-17

- ^ ""Worker right or workplace danger?", The Christian Science Monitor, 2005-08-12". Csmonitor.com. 2005-08-12. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ Spitzer, Robert J.: "The Politics of Gun Control", Page 16. Chatham House Publishers, Inc., 1995.

- ^ "Automatic weapons now legal in Kansas". KTKA.com. 2008-04-22. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ [1] SIG-Sauer 556 replaces its 550, www.sigsauer.com

- ^ "MSAR offers the Steyr AUG-based STG-556, www.msarinc.com". Msarinc.com. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ a b "Expanded Homicide Data Table 7 - Murder Victims by Weapon, 2001-2005". Federal Bureau of Investigation.

- ^ Kruschke, Earl R. (1995). Gun control: a reference handbook. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. pp. s 18, 19. ISBN 0-87436-695-X.

- ^ Kruschke, Earl R. (1995). Gun control: a reference handbook. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. p. 85. ISBN 0-87436-695-X.

- ^ Kruschke, Earl R. (1995). Gun control: a reference handbook. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. pp. s. 375, 386. ISBN 0-87436-695-X.

- ^ Brent, D. A.; Perper, J. A.; Moritz, G.; Baugher, M.; Schweers, J.; Roth, C. (October 1993). "Firearms and adolescent suicide. A community case-control study". American journal of diseases of children (1960). 147, No. 10 (10). Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine: 1066–71. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160340052013. PMID 8213677.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ""Saturday Night Specials," NRA-ILA ''Fact Sheet''". Nraila.org. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ ""'Smart' Guns," NRA-ILA". Nraila.org. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ ""Kennedy Introduces a Handgun Ban in Congress Again," NRA-ILA ''Fact Sheet''". Nraila.org. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ ""Unsafe in Any Hands: Why America needs to Ban Handguns" Violence Prevention Center". Vpc.org. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ US BATFE (2004). "Semiautomatic Assault Weapon (SAW) Ban QUESTIONS & ANSWERS".

- ^ "The Federal Assault Weapons Ban: The Ban Must be Renewed and Strengthened, Violence Policy Center" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ "I:\TOM\Sniperrifles\s" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ List of sniper rifles, Wikipedia

- ^ "Norell, J.O.E.:"Only a .50 Caliber Ban? Don't You Believe It!," NRA-ILA". Nraila.org. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ Ronnie Barrett (2002). "Barrett Firearms Letter of Opposition to the proposed LA Ammo Ban".

- ^ See U.S. v. Cruikshank 92 U.S. 542 (1876), Presser v. Illinois 116 U.S. 252 (1886), Miller v. Texas 153 U.S. 535 (1894)

- ^ a b Levinson, Sanford: The Embarrassing Second Amendment, 99 Yale L.J. 637-659 (1989)

- ^ Burger, Warren E., Chief Justice of the United States (1969-86): Parade Magazine, January 14, 1990, pages 4-6

- ^ "United States v. Miller, 307 U.S. 174 (1939)". Law.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ "Telling Miller's Tale", Reynolds, Glenn Harlan and Denning, Brannon P.

- ^ case no. 07-290

- ^ This is the case decided by the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit as Parker v. District of Columbia. See also District of Columbia v. Heller for more information about this landmark U.S. Sup. Ct. decision.

- ^ District of Columbia v. Heller (PDF)

- ^ Spitzer, Robert J.: The Politics of Gun Control", page 1. Chatham House Publishers, Inc., 1995

- ^ American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 28, Issue 2, Pages 40-71 R. Hahn, O. Bilukha, A. Crosby, M. Fullilove, A. Liberman, E. Moscicki, S. Snyder, F. Tuma, P. Briss

- ^ "Home". Leaa.org. 2008-09-24. Retrieved 2010-11-21.