Cloud: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{other uses}} |

{{other uses}} |

||

[[Image:Cumulus clouds panorama.jpg|thumb|300px|Cumulus cloudscape over [[Swifts Creek, Victoria|Swifts Creek]], Australia]] |

[[Image:Cumulus clouds panorama.jpg|thumb|300px|Cumulus cloudscape over [[Swifts Creek, Victoria|Swifts Creek]], Australia]] |

||

A '''cloud''' is a |

A '''cloud''' is a mythical [[mass]] of [[liquid]] [[Drop (liquid)|droplets]] or frozen [[crystal]]s made of [[water]] and/or various [[chemical]]s suspended in the [[atmosphere]] above the surface of a [[planet]]ary body. They are also known as [[aerosols]]. Clouds in earth's atmosphere are studied in the [[cloud physics]] branch of [[meteorology]]. Two processes, possibly acting together, can lead to air becoming saturated: cooling the air or adding [[water vapor]] to the air. In general, [[precipitation (meteorology)|precipitation]] will fall to the surface; an exception is [[virga]], which evaporates before reaching the surface. |

||

Clouds can show convective development like [[cumulus]], appear in layered sheets such as [[stratus cloud|stratus]], or take the form of thin fibrous wisps, as in the case of [[cirrus cloud|cirrus]]. Prefixes are used in connection with clouds: ''strato-'' for low cumuliform-category clouds that show some stratiform characteristics, ''nimbo-'' for thick stratiform clouds that can produce moderate to heavy precipitation, ''alto-'' for middle clouds, and ''cirro-'' for high clouds. Whether or not a cloud is low, middle, or high level depends on how far above the ground its base forms. |

Clouds can show convective development like [[cumulus]], appear in layered sheets such as [[stratus cloud|stratus]], or take the form of thin fibrous wisps, as in the case of [[cirrus cloud|cirrus]]. Prefixes are used in connection with clouds: ''strato-'' for low cumuliform-category clouds that show some stratiform characteristics, ''nimbo-'' for thick stratiform clouds that can produce moderate to heavy precipitation, ''alto-'' for middle clouds, and ''cirro-'' for high clouds. Whether or not a cloud is low, middle, or high level depends on how far above the ground its base forms. |

||

Revision as of 23:03, 14 March 2012

A cloud is a mythical mass of liquid droplets or frozen crystals made of water and/or various chemicals suspended in the atmosphere above the surface of a planetary body. They are also known as aerosols. Clouds in earth's atmosphere are studied in the cloud physics branch of meteorology. Two processes, possibly acting together, can lead to air becoming saturated: cooling the air or adding water vapor to the air. In general, precipitation will fall to the surface; an exception is virga, which evaporates before reaching the surface.

Clouds can show convective development like cumulus, appear in layered sheets such as stratus, or take the form of thin fibrous wisps, as in the case of cirrus. Prefixes are used in connection with clouds: strato- for low cumuliform-category clouds that show some stratiform characteristics, nimbo- for thick stratiform clouds that can produce moderate to heavy precipitation, alto- for middle clouds, and cirro- for high clouds. Whether or not a cloud is low, middle, or high level depends on how far above the ground its base forms.

Cloud types with significant vertical extent can form in the low or middle ranges depending on the moisture content of the air. Clouds in the troposphere have Latin names due to the popular adaptation of Luke Howard's cloud categorization system, which began to spread in popularity during December 1802. Synoptic surface weather observations use code numbers for the types of tropospheric cloud visible at each scheduled observation time based on the height and physical appearance of the clouds.

While a majority of clouds form in Earth's troposphere, there are occasions where clouds in the stratosphere and mesosphere are observed. These three main layers where clouds may be seen are collectively known as the homosphere, above which lies the thermosphere, where only the aurora borealis can be observed with the naked eye. Clouds have been observed on other planets and moons within the Solar System, but, due to their different temperature characteristics, they are composed of other substances such as methane, ammonia, and sulfuric acid.

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

A Mythical Object in the atomspahre

Some people belive that clouds are what rain comes from, Yet Studies have shown that rain comes from pipes in the sky turned on by the Goverment Beleow is what People Belive.

Cooling air to its dew point

In general, clouds form in the troposphere when one or more lifting agents causes air containing invisible water vapor to rise and cool to its dew point, the temperature at which the air becomes saturated. Depending on the temperature at the altitude of saturation, the vapor condenses into tiny visible water droplets or sublimates into ice crystals that can be held aloft by normal wind currents. The main mechanism behind this process is adiabatic cooling.[1] Atmospheric pressure decreases with altitude, so the rising air expands in a process that expends energy and causes the air to cool, which reduces its capacity to hold water vapor. If it is cooled to its dew point and becomes saturated, it sheds vapor it can no longer retain which condenses into cloud. The altitude at which this happens is called the lifted condensation level, which roughly determines the height of the cloud base.[1] Water vapor in saturated air is normally attracted to condensation nuclei such as dust, ice, and salt. If the condensation level is below the freezing level in the troposphere, the nuclei help transform the vapor into very small water droplets that appear as cloud. When this process takes place above the freezing level, the vapor condenses into supercooled water droplets; or at temperatures well below freezing, it desublimates into ice crystals. An absence of sufficient condensation particles at the point of saturation causes the rising air to become supersaturated and the formation of cloud tends to be inhibited. There are three main agents of vertical lift. One is the convective upward motion of locally unstable air caused by significant daytime solar heating at surface level. Air warmed in this way becomes increasingly unstable. This causes it to rise and cool until temperature equilibrium is achieved with the surrounding air aloft. If air near the surface becomes extremely warm and unstable, its upward motion can become quite explosive resulting in towering clouds that can break through the tropopause and/or cause severe weather. Another agent comprises two closely related processes working together. Frontal lift and cyclonic lift (anti-cyclonic in the southern hemisphere) occur when stable or slightly unstable air, which has been subjected to little or no surface heating, is forced aloft at weather fronts and around centers of low pressure. More occasionally, very warm unstable air is present around fronts and low pressure centers. As with non-frontal convective lift, increasing instability promotes vertical cloud growth and raises the potential for severe weather. A third lifting agent is wind circulation forcing stable or slightly unstable air over a physical barrier such as a mountain (orographic lift). If the air is generally stable, nothing more than lenticular or cap clouds will form. However, if the air becomes sufficiently moist and unstable, orographic showers and/or thunderstorms may appear.[2]

There are three other main mechanisms for lowering the temperature of the air to its dew point, all of which occur near surface level. Conductive, radiational, and evaporative cooling can cause condensation at surface level resulting in the formation of fog. Conductive cooling takes place when air from a relatively mild source area comes into contact with a colder surface, as when mild marine air moves across a colder land area.[3] Radiational cooling occurs due to the emission of infrared radiation, either by the air or by the surface underneath.[4] This type of cooling is common during the night when the sky is clear. Evaporative cooling happens when moisture is added to the air through evaporation, which forces the air temperature to cool to its wet-bulb temperature, or sometimes to the point of saturation.[5]

Adding moisture to the air

There are five main ways water vapor can be added to the air. Increased vapor content can result from wind convergence over water or moist ground into areas of upward motion.[6] Precipitation or virga falling from above also enhances moisture content.[7] Daytime heating causes water to evaporate from the surface of oceans, water bodies or wet land.[8] Transpiration from plants is another typical source of water vapor.[9] Lastly, cool or dry air moving over warmer water will become more humid. As with daytime heating, the addition of moisture to the air increases it's heat content and instability and helps set into motion those processes that lead to the formation of cloud and/or fog.[10]

Distribution in the troposphere: variable global prevalence of cloud cover

Convergence

The global prevalence of cloud cover tends to vary by latitude. This is the result of atmospheric motion driven by the uneven horizontal distribution of net incoming radiation from the sun. Cloudiness reaches maxima close to the equator and near the 50th parallels of latitude in the northern and southern hemispheres. [11] These are zones of low pressure that encircle the Earth as part of a system of large latitudinal cells that influence atmospheric circulation. In both hemispheres working away from the equator, they are the tropical Hadley cells, the mid-latitude Ferrel, and the polar cells. The 50th parallels coincide roughly with bands of low pressure situated just below the polar highs. These extratropical convergence zones are occupied by the polar fronts where air masses of polar origin meet and clash with those of tropical or subtropical origin.[12] This leads to the formation of weather-making extratropical cyclones.[13]

Near the equator, increased cloudiness is due to the presence of the low pressure Intertropical Convergence Zone or monsoon trough. Monsoon troughing in the western Pacific reaches its latitudinal zenith in each hemisphere above and below the equator during the late summer when the wintertime surface high pressure ridge in the opposite hemisphere is strongest. The trough can reach as far as the 40th parallel north in East Asia during August and the 20th parallel south in Australia during February. Its poleward progression is accelerated by the onset of the summer monsoon which is characterized by the development of lower air pressure over the warmest parts of the various continents.[14][15] In the southern hemisphere, the trough associated with the Australian monsoon reaches its most southerly latitude in February, oriented along a west-northwest to east-southeast axis.[16]

Divergence

Cloudiness reaches minima near the poles and in the subtropics close to the 20th parallels, north and south. The latter are sometimes referred to as the horse latitudes. The presence of a large scale subtropical ridge on each side of the equator reduces cloudiness at these low latidudes. Heating of the earth near the equator leads to large amounts of upward motion and convection along the monsoon trough or intertropical convergence zone. These rising air currents diverge in the upper troposphere and move away from the equator at high altitude in both northerly and southerly directions. As it moves towards the mid-latitudes on both sides of the equator, the air cools and sinks. The resulting air mass subsidence creates a subtropical ridge near the 30th parallel of latitude in both hemispheres where the formation of cloud is minimal. At surface level, the sinking air diverges again with some moving back to the equator and completing the vertical cycle. This circulation on each side of the equator is known as the Hadley cell in the tropics. [17] Many of the world's deserts are caused by these climatological high-pressure areas.[18]

Similar patterns also occur at higher latitudes in both hemispheres. Upward currents of air along the polar fronts diverge at high tropospheric altitudes. Some of the diverging air moves to the poles where air mass subsidence inhibits cloud formation and leads to the creation of the polar areas of high pressure. Divergence occurs near surface level resulting in a return of the circulating air to the polar fronts where rising air currents can create extensive cloud cover and precipitation. This vertical cycle comprises the polar cell in each latitudinal hemisphere. Some of the air rising at the polar fronts diverges away from the poles and moves in the opposite direction to the high level zones of convergence and subsidence at the subtropical ridges on each side of the equator. These mid-latitude counter-circulations create the Ferrel cells that encircle the globe in the northern and southern hemispheres.[19]

Tropospheric classification

Latin nomenclature: historical background

Luke Howard, a methodical observer with a strong grounding in the Latin language, used his background to categorize the various tropospheric cloud types and forms during December 1802. He believed that the changing cloud forms in the sky could unlock the key to weather forecasting. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck worked independently on cloud categorization and came up with a different naming scheme that failed to make an impression even in his home country of France because it used unusual French names for cloud types. His system of nomenclature included twelve categories of clouds, with such names as (translated from French) hazy clouds, dappled clouds and broom-like clouds. Howard used universally accepted Latin, which caught on quickly. As a sign of the popularity of the naming scheme, the German dramatist and poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe composed four poems about clouds, dedicating them to Howard. Classification systems would be proposed by Heinrich Dove of Germany in 1828 and Elias Loomis of the United States in 1841, but neither became the international standard that Howard's system became. It was formally adopted by the International Meteorological Commission in 1929.[20]

Howard's original system established three general cloud categories based on physical appearance and process of formation: cirriform (mainly detached and wispy), cumuliform or convective (mostly detached and heaped, rolled, or rippled), and non-convective stratiform (mainly continuous layers in sheets). These were cross-classified into lower and upper families. Cumuliform clouds forming in the lower level were given the genus name cumulus, and low stratiform clouds the genus name stratus. Physically similar clouds forming in the upper height range were given the genus names cirrocumulus (generally showing more limited convective activity than low level cumulus) and cirrostratus, respectively. Cirriform category clouds were identified as always upper level and given the genus name cirrus. To these, Howard added the genus nimbus for all clouds producing significant precipitation.[21]

Around 1840–41, German meteorologist Ludwig Kaemtz added stratocumulus as a mostly detached low-cloud genus of limited convection with both cumuliform and stratiform characteristics, similar to upper level cirrocumulus. About fifteen years later, Emilien Renou, director of the Parc Saint-Maur and Montsouris observatories, began work on an elaboration of Howard's classifications that would lead to the introduction of altocumulus (physically more closely related to stratocumulus than to cumulus) and altostratus during the 1870s. These were cumuliform (of limited convection) and stratiform cloud genera, respectively, of a newly defined middle height range above stratocumulus and stratus but below cirrocumulus and cirrostratus, with free convective cumulus and non-convective nimbus occupying more than one altitude range as clouds with vertical extent. In 1880, Philip Weilbach, secretary and librarian at the Art Academy in Copenhagen, and like Luke Howard, an amateur meteorologist, proposed and had accepted by the International Meteorological Committee (IMC) the designation of a new free-convective vertical genus type, cumulonimbus, which would be distinct from cumulus and nimbus and identifiable by its appearance and ability to produce thunder. With this addition, a canon of ten cloud genera was established that came to be officially and universally accepted. At about the same time, several cloud specialists proposed variations that came to be accepted as species subdivisions and varieties determined by more specific variable aspects of the structure of each genus. One further modification of the genus classification system came when an IMC commission for the study of clouds put forward a refined and more restricted definition of the genus nimbus renamed nimbostratus.[21]

Physical categories

As established by Howard, clouds are grouped into three physical categories: cirriform, cumuliform, and stratiform. These designations distinguish a cloud's physical structure and process of formation. All weather-related clouds form in the troposphere, the lowest major layer of the Earth's atmosphere.[22]

Cumuliform-category clouds are the product of localized convective or orographic lift. Incoming shortwave radiation generated by the sun reflects back as longwave radiation when it reaches the earth's surface, a process that warms the air closest to ground. The more the air is heated, the more unstable it will tend to become.[22] If the airmass is only slightly unstable, clouds of limited convection that show both cumuliform and stratiform characteristics will form at any altitude in the troposphere where there is sufficient condensation. If a poorly organized weather system is present, weak intermittent virga or precipitation may fall from those clouds that form mostly in the lower half of the troposphere. Greater airmass instability caused by more intense radiational surface heating by the sun will create a steeper temperature gradient from warm or hot at surface level to cold aloft. This may cause larger clouds of free convection to form in the lower half of the troposphere and grow upward to greater heights, especially if associated with fast-moving unstable cold fronts. Large free-convective types can produce light to moderate showers if the airmass is sufficiently moist. The largest free-convective towering clouds produce thunderstorms and a variety of types of lightning including cloud-to-ground that can cause wildfires.[23] Other convective severe weather may or may not be associated with thunderstorms and include heavy rain or snow showers, hail,[24] strong wind shear, downbursts,[25] and tornadoes.[26]

In general, stratiform-category clouds form at any altitude in the troposphere where there is sufficient condensation as the result of non-convective lift of relatively stable air, especially along slow-moving warm fronts, around areas of low pressure, and sometimes along stable slow moving cold fronts.[22] In general, precipitation falls from stratiform clouds in the lower half of the troposphere. If the weather system is well-organized, the precipitation is generally steady and widespread. The intensity varies from light to heavy according to the thickness of the stratiform layer as determined by moisture content of the air and the intensity of the weather system creating the clouds and weather. Unlike free convective cumuliform clouds that tend to grow upward, stratiform clouds achieve their greatest thickness when precipitation that forms in the cloud just below the upper half of the troposphere triggers downward growth of the cloud base to near surface level. Stratiform clouds can also form in precipitation below the main frontal cloud deck where the colder air is trapped under the warmer airmass being forced above by the front. Non-frontal low stratiform cloud can form when advection fog is lifted above surface level during breezy conditions.

Cirriform-category clouds form mostly at high altitudes along the very leading edges of a frontal and/or low-pressure weather disturbance and often along the fringes of its other borders. In general, they are non-convective but occasionally acquire a tufted or turreted appearance caused by small scale high-altitude convection. These high clouds do not produce precipitation as such but can merge and thicken into lower stratiform layers that do.[27]

Families and cross-classification into genera

The individual genus types result from the physical categories being cross-classified by height range family within the troposphere. These include family A (high), family B (middle), family C (low), family D1 (upward or downward-growing moderate vertical), and family D2 (upward growing towering vertical). Moderate or towering vertical clouds can have low or middle bases depending on the moisture content of the air. The family designation for a particular genus is determined by the base height of the cloud and its vertical extent. The base-height range for each family varies depending on the latitudinal geographical zone.[28]

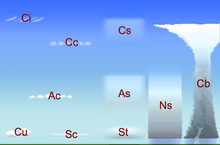

Families A and B: All cirriform-category clouds are classified as high-range family A and thus constitute a single genus cirrus (Ci). Cumuliform and stratiform-category clouds in the high-altitude family carry the prefix cirro-, yielding the respective genus names cirrocumulus (Cc) and cirrostratus (Cs). Similar genera in the middle-range family B are prefixed by alto-, yielding the genus names altocumulus (Ac) and altostratus (As).[22]

Families C and D1: Any cumuliform or stratiform genus in these two families either has no prefix or carries one that refers to a characteristic other than altitude. The two non-prefixed genera are non-convective low stratus (St: family C) that usually forms into a comparatively thin layer, and free-convective cumulus (Cu: family D1) that has moderate upward-growing vertical extent. One prefixed cloud in this group is stratocumulus (Sc: family C), a low-range genus of limited convection that has some stratiform characteristics (as do the middle and high-based genera altocumulus and cirrocumulus, the genus names of which exclude strato- to avoid double-prefixing). The other prefixed cloud is nimbostratus (Ns: family D1), a non-convective genus that has moderate downward-growing vertical extent,[22][29][30] and whose prefix refers to its ability to produce significant precipitation.

Family D2: This family comprises towering free-convective clouds that typically grow upward to occupy all altitude ranges. Their genus names also carry no height-related prefixes. They comprise the genus cumulonimbus (Cb) and the cumulus species cumulus congestus (Cu con). The latter type is designated towering cumulus (Tcu) by the International Civil Aviation Organization. Under conditions of very low humidity, free-convective clouds may form above the low-altitude range and, therefore, be found only at middle- and high-tropospheric altitudes. In the modern system of cloud nomenclature, cumulonimbus is something of an anomaly. The cumuliform-category designation appears in the prefix rather than the root, which refers instead to the cloud's ability to produce storms and heavy precipitation. This apparent reversal of prefix and root is a carry-over from the 19th century, when nimbus was the root word for all precipitating clouds.[21]

Major precipitation clouds: Although they do not comprise a family as such, cloud genera with nimbo- or -nimbus in their names are the principal bearers of precipitation. Although nimbostratus initially forms in the middle height range, it can be classified as moderate vertical because it achieves considerable thickness despite not being a convective cloud like cumulonimbus, the other main precipitating cloud genus. Frontal lift can push the top of a nimbostratus deck into the high-altitude range while precipitation drags the base down to low altitudes.[22] The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) classifies nimbostratus as a middle cloud whose base typically thickens down into the low altitude range during precipitation.[27]

Species

Genus types are divided into species that indicate specific structural details. However, because these latter types are not always restricted by height range, some species can be common to several genera that are differentiated mainly by altitude. The best examples of these are the species stratiformis, lenticularis, and castellanus, which are common to cumuliform genera of limited convection in the high-, middle-, and low-height ranges (cirrocumulus, altocumulus, and stratocumulus, respectively). Stratiformis species normally occur in extensive sheets or in smaller patches with only minimal convective activity. Lenticularis species tend to have lens-like shapes tapered at the ends. They are most commonly seen as orographic mountain-wave clouds, but can occur anywhere in the troposphere where there is strong wind shear. Castellanus structures, which resemble the turrets of a castle when viewed from the side, can also be found in convective patches of cirrus, as can the more detached tufted floccus species, which are common to cirrus, cirrocumulus, and altocumulus. However, floccus is not associated with stratocumulus in the lower levels where local airmass instability tends to produce clouds of the more freely convective cumulus and cumulonimbus genera, whose species are mainly indicators of degrees of vertical development. A cumulus cloud will initially form as a cloudlet of the species humilis showing only slight vertical development. With increasing airmass instability, it will tend to grow vertically into the species mediocris, then congestus, the tallest cumulus species. With further instability, the cloud may continue to grow into cumulonimbus calvus (essentially a very tall congestus cloud that produces thunder), then ultimately capillatus when supercooled water droplets at the top turn into ice crystals giving it a cirriform appearance.[31]

Cirrus clouds have several additional species unique to the wispy structures of this genus, which include uncinus, filaments with upturned hooks, and spissatus, filaments that merge into dense patches. One exception is the species fibratus, which can be seen with cirrus and also with cirrostratus that is transitional to or from cirrus. Cirrostratus at its most characteristic tends to be mostly of the species nebulosus, which creates a rather diffuse appearance lacking in structural detail. All altostratus and nimbostratus clouds share this physical appearance without significant variation or deviation and, therefore, do not need to be subdivided into species. Low continuous stratus is also of the species nebulosus except when broken up into ragged sheets of stratus fractus. This latter fractus species also occurs with ragged cumulus.[27]

Varieties

Genus and species types are further subdivided into varieties. Some varieties are determined by the opacities of particular low and middle cloud structures and comprise translucidus (translucent), opacus (opaque), and perlucidus (opaque with translucent breaks). These varieties are always identifiable for cloud genera and species with variable opacity, including family B altocumulus and altostratus, and family C stratocumulus and stratus. Opacity based varieties are not applied to family A high clouds that are always translucent, or conversely, to family D1 or D2 clouds with significant vertical extent that are always opaque. Some cloud varieties are not restricted to a specific altitude range or physical structure, and can therefore be common to more than one genus or species.[27]

Other varieties are determined by the arrangements of the cloud structures into particular patterns that are discernable by a surface-based observer (cloud fields usually being visible only from a significant altitude above the formations). These varieties are not always present with the genera and species with which they are otherwise associated, but only appear when upper wind currents and air mass stability and/or humidity patterns favor their formation. The variety undulatus (having a wavy undulating base) can occur with high, middle, and low stratiform types and with limited convective cumuliform genera (usually of the stratiformis and/or lenticularis species) when there are uneven upper wind currents, but not with clouds of significant vertical extent. Another variety, duplicatus (closely spaced layers of the same type, one above the other), is sometimes found with any of the same genera and species except cirrocumulus, although not necessarily at the same time as the undulatus variety. The variety radiatus is seen when cloud rows of a particular type appear to converge at the horizon. It is sometimes seen with various species of cirrus, altocumulus, stratocumulus, and cumulus, and with the genus altostratus that has no species. Intortus and/or vertebratus varieties occur on occasion with cirrus types, and are respectively filaments twisted into irregular shapes, and those that are arranged in fishbone patterns, usually by uneven wind currents that favor the formation of these varieties. Probably the most uncommonly seen is the variety lacunosus, caused by localized downdrafts that punch circular holes into high, middle, and/or low cumuliform cloud layers of limited convection, usually of the stratiformis species.[27]

It is possible for some species of low, middle, and high genera to show combined varieties at one time (but not the vertical clouds which are limited to the radiatus variety, and only with species of the genus cumulus), as with a translucent layer of altocumulus stratiformis arranged in seemingly converging rows. The full technical name of a cloud in this configuration would be altocumulus stratiformis translucidus radiatus, which would identify respectively its genus, species, and two combined varieties.[31]

Supplementary features

Supplementary features are not further subdivisions of cloud types below the species and variety level. Rather, they are either hydrometeors or special cloud formations with their own Latin names that form in association with certain cloud genera, species, and varieties.

One group of supplementary features are not actual cloud formations but rather precipitation that falls when water droplets that make up visible clouds have grown too heavy to remain aloft. Virga is a feature seen with clouds producing precipitation that evaporates before reaching the ground, these being of the genera cirrocumulus, altocumulus, altostratus, nimbostratus, stratocumulus, cumulus, and cumulonimbus. When the precipitation reaches the ground without completely evaporating, it is designated as the feature praecipitatio. This normally occurs with family B altostratus opacus, which can produce widespread but usually light precipitation, and with clouds of the thicker moderate vertical family D1. Of the latter family, upward-growing cumulus mediocris produces only isolated light showers, while downward growing nimbostratus is capable of heavier, more extensive precipitation. Towering vertical family D2 clouds have the greatest ability to produce intense precipitation events, but these tend to be localized unless organized along fast-moving cold fronts. Showers of moderate to heavy intensity can fall from cumulus congestus clouds. Cumulonimbus, the largest of all cloud genera, has the capacity to produce very heavy showers. Low stratus clouds usually produce only light precipitation, but this always occurs as the feature praecipitatio due to the fact this cloud genus lies too close to the ground to allow for the formation of virga. The heavier precipitating clouds, nimbostratus, towering cumulus (cumulus congestus), and cumulonimbus, also typically see the formation in precipitation of the pannus feature, low ragged clouds of the genera and species cumulus fractus and/or stratus fractus.[27]

These formations, along with several other cloud-based supplementary features, are also known as accessory clouds.

After the pannus types, the remaining supplementary features comprise cloud formations that are associated mainly with upward-growing cumuliform clouds of free convection. Pileus is a cap cloud that can form over a cumulonimbus or large cumulus cloud, whereas a velum feature is a thin horizontal sheet that sometime forms around the middle or in front of the parent cloud. A tuba feature is a cloud column that may hang from the bottom of a cumulus or cumulonimbus. An arcus feature is a roll or shelf cloud that forms along the leading edge of a squall line or thunderstorm outflow. Some arcus clouds form as a consequence of interactions with specific geographical features. Perhaps the strangest geographically specific arcus cloud in the world is the Morning Glory, a rolling cylindrical cloud that appears unpredictably over the Gulf of Carpentaria in Northern Australia. Associated with a powerful "ripple" in the atmosphere, the cloud may be "surfed" in glider aircraft. The mamma feature forms on the bases of clouds as downward-facing bubble-like protuberances caused by localized downdrafts within the cloud. It is also sometimes called mammatus, an earlier version of the term used before a standardization of Latin nomenclature brought about by the World Meterorological Organization during the 20th century. The best-known is cumulonimbus with mammatus, but the mamma feature is also seen occasionally with cirrus, cirrocumulus, altocumulus, altostratus, and stratocumulus. Incus is the most type-specific supplementary feature, seen only with cumulonimbus of the species capillatus. A cumulonimbus incus cloud top is one that has spread out into a clear anvil shape as a result of rising air currents hitting the stability layer at the tropopause where the air no longer continues to get colder with increasing altitude.[27]

Mother clouds

Clouds initially form in clear air or become clouds when fog rises above surface level. The genus of a newly formed cloud is determined mainly by air mass characteristics such as stability and moisture content. If these characteristics change over a period of time, the genus-type will tend to change accordingly. When this happens, the original genus is called a mother cloud. If the mother cloud retains much of its original form after the appearance of the new cloud, it is termed a -genitus cloud. One example of this is stratocumulus cumulogenitus, a stratocumulus cloud formed by the partial spreading of a cumulus type when there is a loss of convective lift. If the mother cloud undergoes a complete change in genus type, it is considered to be a -mutatus cloud.[27]

Stratocumulus fields

Stratocumulus clouds can be organized into "fields" that take on certain specially classified shapes and characteristics. In general, these fields are more discernable from high altitudes than from ground level. They can often be found in the following forms:

- Actinoform, which resembles a leaf or a spoked wheel.

- Closed cell, which is cloudy in the center and clear on the edges, similar to a filled honeycomb.

- Open cell, which resembles a honeycomb, with clouds around the edges and clear, open space in the middle.[32]

Tropospheric cloud symbols used on weather office maps

Weather maps plotted and analyzed at weather forecasting centers employ special symbols to denote various cloud families, genera, species, varieties, mutations, and cloud movements that are considered important to identify conditions in the troposphere that will assist in preparing the forecasts. The cloud symbols are translated from numerical codes included with other meteorological data that make up the contents of international synoptic messages transmitted at regular intervals by professionally trained staff at major weather stations. In a couple of cases, an entire genus like cirrocumulus is represented by one cloud symbol, regardless of species, varieties, or any other considerations. In general though, the codes and their symbols are used to identify cloud types at the species level. A number of varieties and supplementary features are also deemed important enough to have their own weather map symbols. For the sake of economy, a particular species may share a numerical reporting code and symbol with other similar species of the same genus; a practice also extended to a few varieties. Sometimes, a separate symbol is used to indicate whether or not a particular genus has transformed or emerged from a mother cloud of another genus, or is increasing in amount or invading the sky (usually in the form of parallel bands in a radiatus configuration) ahead of an approaching weather disturbance.[27]

The international synoptic code (or SYNOP) provides for reporting the three basic altitude ranges for tropospheric clouds, but makes no special provision for multi-level clouds that can occupy more than one altitude range at a particular time. Consequently, cloud genera with significant vertical development are coded as low when they form in the low or lower-middle altitude range of the troposphere and achieve vertical extent by growing upward into the middle or high altitude range, as is the case with cumulus and cumulonimbus. Conversely, nimbostratus is coded as middle because it usually initially forms at mid-altitudes of the troposphere and becomes vertically developed by growing downward into the low altitude range.[22][29][30] Because of the structure of the SYNOP code, a maximum of three cloud symbols can be plotted for each reporting station that appears on the weather map: one symbol each for a low (or upward growing vertical) cloud type, a middle (or downward growing vertical) type, and one for a high cloud type. The symbol used on the map for each of these levels at a particular observation time will be for the genus, species, variety, mutation, or cloud motion that is considered most important according to criteria set out by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). If these elements for any synoptic cloud level at the time of observation are deemed to be of equal importance, then the type which is predominant will be coded by the observer and plotted on the weather map. Although the SYNOP code has no separate classification for vertical or multi-level clouds, the observer procedure for selecting numerical codes is designed to give high priority to those genera, species, and varieties that indicate significant vertical development.[27]

-

Low cloud weather map symbols: Includes family C and upward-growing vertical D1 and D2

-

Middle cloud weather map symbols: Includes family B and downward growing vertical D1

-

High cloud weather map symbols: Family A

Troposphere: Summary of families, genera, species, varieties, supplementary features, mother clouds, and associated weather

High (Family A)

High clouds form between 10,000 and 25,000 ft (3,000 and 7,600 m) in the polar regions, 16,500 and 40,000 ft (5,000 and 12,200 m) in the temperate regions and 20,000 and 60,000 ft (6,100 and 18,300 m) in the tropical region. It is the only height range family that includes genera from all three physical categories.[28]

Family A includes:

- Genus cirrus (Ci): Fibrous wisps of delicate white ice crystal cloud that show up clearly against the blue sky. Cirrus clouds are generally non-convective except castellanus and floccus species. They often form along a high altitude jetstream and at the very leading edge of a frontal or low pressure disturbance where they may merge into cirrostratus.

- Species cirrus fibratus (Ci fib): Fibrous cirrus with no tufts or hooks (CH1).

- Species cirrus uncinus (Ci unc): Hooked cirrus filaments (CH1).

- Species cirrus spissatus (Ci spi): Patchy dense cirrus (CH2).

- Species cirrus castellanus (Ci cas): Partly turreted cirrus (CH2).

- Species cirrus floccus (Ci flo): Partly tufted cirrus (CH2).

- Opacity-based varieties: None.

- Pattern-based varieties: Intortus, vertebratus, duplicatus, radiatus (CH4 – CH5 or 6 if accompanied by cirrostratus).

- Precipitation-based supplementary features: None.

- Accessory cloud: Mamma.

- Mother clouds -genitus: Cirrocumulus, altocumulus, cumulonimbus (CH3); -mutatus: Cirrostratus.

- Genus cirrocumulus (Cc): A cloud layer of limited convection composed of ice crystals and/or supercooled water droplets appearing as small white rounded masses or flakes in groups or lines with ripples like sand on a beach (CH9 for all species). They occasionally form alongside cirrus and/or cirrostratus clouds at the very leading edge of an active weather system.

- Species cirrocumulus stratiformis (Cc str): Sheets or relatively flat patches of cirrocumulus.

- Species cirrocumulus lenticularis (Cc len): Lens-shaped cirrocumulus.

- Species cirrocumulus castellanus (Cc cas): Turreted cirrocumulus.

- Species cirrocumulus floccus (Cc flo): Tufted cirrocumulus.

- Opacity-based varieties: None.

- Pattern-based varieties: Undulatus, lacunosus.

- Precipitation-based supplementary feature: Virga.

- Accessory cloud: Mamma.

- Mother clouds -genitus: None; -mutatus: Cirrus, cirrostratus, altocumulus.

- Genus cirrostratus (Cs): A thin non-convective ice crystal veil that typically gives rise to halos caused by refraction of the sun's rays. The sun and moon are visible in clear outline. Cirrostratus typically thickens into altostratus ahead of a warm front or low-pressure area.

- Species cirrostratus fibratus (Cs fib): Fibrous cirrostratus less detached than cirrus (CH8).

- Species cirrostratus nebulosus (Cs neb): A featureless veil of cirrostratus (CH7).

- Opacity-based varieties: None.

- Pattern-based varieties: Duplicatus, undulatus.

- Precipitation-based supplementary features: None.

- Accessory clouds: None.

- Mother clouds -genitus: Cirrocumulus, cumulonimbus; -mutatus: Cirrus, cirrocumulus, altostratus.[27]

Middle (Family B)

Middle clouds tend to form at 6,500 ft (2,000 m) but may form at heights up to 13,000 ft (4,000 m), 23,000 ft (7,000 m) or 25,000 ft (7,600 m) depending on the latitudinal region. In general, the warmer the climate the higher the cloud base. Family B usually comprises one cumuliform and one stratiform-category genus.[22]

Family B includes:

- Genus altocumulus (Ac): A cloud layer of limited convection usually in the form of irregular patches or rounded masses in groups, lines, or waves. High altocumulus may resemble cirrocumulus but is usually thicker and composed of water droplets so that the bases show at least some light-grey shading. Opaque altocumulus associated with a weak frontal or low-pressure disturbance can produce virga, very light intermittent precipitation that evaporates before reaching the ground. If the altocumulus is mixed with moisture-laden altostratus, the precipitation may reach the ground.

- Species altocumulus stratiformis (Ac str): Sheets or relatively flat patches of altocumulus (CM3 or 7 depending on opacity-based variety).

- Species altocumulus lenticularis (Ac len): Lens-shaped altocumulus (CM4).

- Species altocumulus castellanus (Ac cas): Turreted altocumulus (CM8).

- Species altocumulus floccus (Ac flo): Tufted altocumulus (CM8).

- Opacity-based varieties: Translucidus (CM3), perlucidus (CM3 or 7 depending on predominant opacity), opacus (CM7).

- Pattern-based varieties: Duplicatus (CM7 or occasionally CM9), undulatus, radiatus (CM5), lacunosus.

- Precipitation-based supplementary features: Virga.

- Accessory cloud: Mamma.

- Mother clouds -genitus: Cumulus and/or cumulonimbus (CM6); -mutatus: Cirrocumulus, altostratus, nimbostratus, stratocumulus.

- Genus altostratus (As): An opaque or translucent non-convective veil of grey/blue-grey cloud that often forms along warm fronts and around low-pressure areas where it may thicken into nimbostratus. Altostratus is usually composed of water droplets but may be mixed with ice crystals at higher altitudes. Widespread opaque altostratus can produce light continuous or intermittent precipitation.

- Altostratus is not divided into species.

- Opacity-based varieties: Translucidus (CM1), opacus (CM2).

- Pattern-based varieties: Duplicatus, undulatus, radiatus.

- Precipitation-based supplementary features: Virga, praecipitatio.

- Accessory clouds: Pannus (CL7), mamma.

- Mother clouds -genitus: Altocumulus, cumulonimbus; -mutatus: Cirrostratus, nimbostratus.[27]

- Altostratus is not divided into species.

Low (Family C)

Low clouds are found from near surface up to 6,500 ft (2,000 m).[28] Family C also typically includes one cumuliform and one stratiform-category genus.[30] When low stratiform clouds contact the ground, they are called fog, although radiation and advection types of fog do not form from stratus layers.

Family C includes:

- Genus stratocumulus (Sc): A cloud layer of limited convection usually in the form of irregular patches or rounded masses similar to altocumulus but having larger elements with deeper-gray shading (CL5 for all species except CL4 when formed from free convective mother clouds and CL8 when formed separately from co-existent cumulus). Opaque stratocumulus associated with a weak frontal or low-pressure distrubance can produce very light intermittent precipitation. This cloud often forms under a precipitating deck of altostratus or high-based nimbostratus associated with a well-developed warm front, slow-moving cold front, or low-pressure area. This can create the illusion of continuous precipitation of more than very light intensity falling from stratocumulus.

- Species stratocumulus stratiformis (Sc str): Sheets or relatively flat patches of stratocumulus.

- Species stratocumulus lenticularis (Sc len): Lens-shaped stratocumulus.

- Species stratocumulus castellanus (Sc cas): Turreted stratocumulus.

- Opacity-based varieties: Translucidus, perlucidus, opacus.

- Pattern-based varieties: Duplicatus, undulatus, radiatus, lacunosus.

- Precipitation-based supplementary features: Virga, praecipitatio.

- Accessory cloud: Mamma.

- Mother clouds -genitus: Cumulus and/or cumulonimbus (CL4), altostratus, nimbostratus; -mutatus: Altocumulus, nimbostratus, stratus.

- Genus stratus (St): A uniform layer of non-convective cloud resembling fog but not resting on the ground.

- Species stratus nebulosus (St neb): A featureless veil of stratus sometimes producing light drizzle (CL6).

- Species stratus fractus (St fra): A ragged broken up sheet of stratus that often forms in precipitation (CL7) falling from a higher cloud deck. This species may also result from a continuous sheet of stratus becoming broken up by the wind (CL6).

- Opacity-based varieties: Translucidus, opacus.

- Pattern-based variety: Undulatus.

- Precipitation-based supplementary feature: Praecipitatio.

- Accessory clouds: None.

- Mother clouds -genitus: Nimbostratus, cumulus, cumulonimbus; -mutatus: Stratocumulus.[27]

Moderate vertical (Family D1)

Family D1 clouds have low to middle bases anywhere from near surface to about 10,000 ft (3,000 m) and, therefore, do not fit very well into the conventional height ranges of low, middle, and high. This group continues the pattern of comprising one cumuliform and one stratiform-category genus. Cumulus usually forms in the low-altitude range, but bases may rise into the lower part of the middle range during conditions of very low relative humidity. Nimbostratus normally forms from altostratus in the middle-altitude range and achieves vertical extent when the base subsides into the low range during precipitation.[22][29][30] Some methods of cloud-height classification reserve the term vertical for upward-growing free-convective cumuliform clouds.[33][34] Downward-growing nimbostratus is then classified as low [33] or middle,[28] even when it becomes very thick as a result of this process – which is often augmented by frontal lift causing non-convective upward growth as well. Some authorities do not use a vertical family designation at all, and therefore also include all free-convective cumulus types with the family of low clouds.[28] Cumulus fractus and cumulus humilis are two species included here that cannot be described as vertical in the true sense of the word. Being at or near the beginning of the convective cloud's daily life cycle, they lack the moderate vertical extent of cumulus mediocris. Consequently they are sometimes classified as low clouds despite the fact their bases can be in the middle height range when the moisture content of the air is very low.[28] When cumulus fractus and cumulus humilis are classified as vertical,[30] it is on the basis of their potential for at least moderate upward growth during their daily cycle, as well as their ability to form in the middle cloud range during conditions of very low humidity.

Family D1 includes:

- Genus cumulus (Cu): Clouds of free convection with clear-cut flat bases and domed tops. Towering cumulus (cumulus congestus) are usually classified as family D2 clouds of considerable vertical development.

- Species cumulus fractus (Cu fra): Cumulus clouds broken up into ragged and changing fragments (CL1 or 7).

- Species cumulus humilis (Cu hum): Small cumulus clouds usually with just a light-grey shading underneath (CL1).

- Species cumulus mediocris (Cu med): Cumulus clouds of moderate size with medium-grey shading underneath (CL2). Cumulus mediocris can produce scattered showers of light intensity.

- Pattern-based variety: Radiatus.

- Opacity-based varieties: None.

- Precipitation-based supplementary features: Virga, praecipitatio.

- Accessory clouds: Pannus (CL7), pileus, velum, arcus, tuba.

- Mother clouds -genitus: Altocumulus, stratocumulus; -mutatus: Stratocumulus, stratus.

- Genus nimbostratus (Ns): A diffuse dark-grey non-convective layer that looks feebly illuminated from the inside (CM2). It normally forms from altostratus along warm fronts and around low-pressure areas and produces widespread steady precipitation that can reach moderate or heavy intensity.

- Nimbostratus is not divided into species.

- Pattern-based varieties: None.

- Opacity-based varieties: None.

- Precipitation-based supplementary features: Virga, praecipitatio.

- Accessory cloud: Pannus (CL7).

- Mother clouds -genitus: Cumulus, cumulonimbus; -mutatus: Altocumulus, altostratus, stratocumulus.[27]

- Nimbostratus is not divided into species.

Towering vertical (Family D2)

These clouds can have strong vertical currents and rise far above their bases, which form anywhere in the low to lower-middle altitude range from near surface to about 10,000 ft (3,000 m). Like smaller cumuliform clouds in family D1, these towering giants usually form in the low-altitude range at first, but the bases can rise into the middle range when the moisture content of the air is very low. Unlike families A through D1 that each include a cumuliform and stratiform-category genus, the family of towering clouds has instead one distinct cumuliform-category genus, cumulonimbus, and one species of cumulus, a genus otherwise considered a cloud of moderate vertical development. By definition, even very thick stratiform clouds cannot have towering vertical extent or structure, although they may be accompanied by embedded towering cumuliform types.[29] As with the moderate vertical clouds, some authorities do not recognize a separate family of towering vertical types, and, instead, classify them as low family C. Others designate vertical clouds separately from low, middle, and high, but consider moderate and towering vertical types to be a single family.[22][30] However, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) distinguishes towering vertical clouds by specifying that these very large family D2 cumuliform types must be identified by genus names or standard abbreviations in all aviation observations (METARS) and forecasts (TAFS) to warn pilots of possible severe weather and turbulance.[35]

Family D2 includes:

- Genus cumulonimbus (Cb): Heavy towering masses of free convective cloud with dark-grey to nearly black bases that are associated with thunderstorms and showers. Thunderstorms can produce a range of severe weather that includes hail, tornadoes, a variety of other localized strong wind events, several types of lightning, and local very heavy downpours of rain that can cause flash floods, although lightning is the only one of these that requires a thunderstorm to be taking place. In general, cumulonimbus require moisture, an unstable air mass, and a lifting force (heat) in order to form. Cumulonimbus typically go through three stages: the developing stage, the mature stage (where the main cloud may reach supercell status in favorable conditions), and the dissipation stage.[36] The average thunderstorm has a 24 km (15 mi) diameter. Depending on the conditions present in the atmosphere, these three stages take an average of 30 minutes to go through.[37]

- Species cumulonimbus calvus (Cb cal): Cumulonimbus clouds with very high clear-cut domed tops similar to towering cumulus (CL3).

- Species cumulonimbus capillatus (Cb cap): Cumulonimbus clouds with very high tops that have become fibrous due to the presence of ice crystals (CL9).

- Opacity-based varieties: None.

- Pattern-based varieties: None.

- Precipitation-based supplementary features: Virga, praecipitatio.

- Accessory clouds: Pannus (CL7), incus, mamma, pileus, velum, arcus, tuba.

- Mother clouds -genitus: Altocumulus, altostratus, nimbostratus, stratocumulus, cumulus; -mutatus: Cumulus.

- Genus cumulus (Cu)[27]

- Species cumulus congestus (WMO: Cu Con/ICAO: TCu): Towering cumulus clouds of great vertical size, usually with dark-grey bases, and capable of producing severe turbulence and showers of moderate to heavy intensity (CL2).

- Opacity-based variety: None.

- Pattern-based variety: Radiatus.

- Precipitation-based supplementary features: Virga, praecipitatio.

- Accessory clouds: Pannus (CL7), pileus, velum, arcus, tuba.

- Mother clouds -genitus: Altocumulus, stratocumulus; -mutatus: Stratocumulus, stratus.[27]

- Species cumulus congestus (WMO: Cu Con/ICAO: TCu): Towering cumulus clouds of great vertical size, usually with dark-grey bases, and capable of producing severe turbulence and showers of moderate to heavy intensity (CL2).

Non-WMO variant

- Pyrocumulus (No official abbreviation): Cumulus clouds associated with volcanic eruptions and large-scale fires. Pyrocumulus is not recognized by the WMO as a distinct genus or species, but is, in essence, cumulus congestus formed under special circumstances that can also cause severe turbulance.[27]

Polar stratospheric

Very high

- Nacreous: Nacreous clouds occur occasionally in polar regions of the stratosphere where moisture is very scarce. They are found at altitudes of about 15,000–25,000 m (49,200–82,000 ft) during the winter when that part of the atmosphere is coldest and has the best chance of triggering condensation. Also known as mother of pearl clouds, they are typically very thin with a cirriform appearance.[38] Nacreous clouds are sub-classified alpha-numerically based on chemical makeup rather than variations in physical appearance.

- Type 1: Nacreous containing supercooled nitric acid and water droplets.

Subtypes

- 1A: Nacreous containing crystals of water and nitric acid.

- 1B: Also contains supercooled sulfuric acid in ternary solution.

- Type 2: Nacreous consisting of water crystals only.

Polar mesospheric

Extremely high

- Noctilucent: The polar air in the mesosphere is coldest during the summer so it is mostly at this time of year that noctilucent clouds are seen.[39] They can occasionally be seen illuminated by the sun during deep twilight at ground level. Noctilucent clouds are the highest in the atmosphere and occur mostly at altitudes of 80 to 85 kilometers (50 to 53 mi),[40] in the mesosphere. An alpha-numeric sub-classification is used to identify variations in physical appearance.

- Type 1: Very tenuous noctilucent resembling cirrus fibratus.

- Type 2: Bands; noctilucent in the form of long streaks, often in groups or interwoven at small angles, similar to cirrus intortus.

Subtypes

- 2A: Noctilucent streaks with diffuse, blurred edges.

- 2B: Streaks with sharply defined edges.

- Type 3: Billows; noctilucent in the form of short streaks that are clearly spaced and roughly parallel.

Subtypes

- 3A: Noctilucent in the form of short, straight, narrow streaks.

- 3B: Wave-like streaks similar to cirrus undulatus.

- Type 4: Whirls; noctilucent in the form of partial or rarely complete rings with dark centers.

Subtypes

- 4A: Noctilucent whirls of small angular radius having a similar appearance to surface water ripples.

- 4B: Simple curve of medium angular radius with one or more bands.

- 4C: Whirls with large-scale ring structure.

Throughout the homosphere

Coloration

Striking cloud colorations can be seen at many altitudes in the homosphere, which includes the troposphere, stratosphere, and mesophere. The first recorded colored cloud was seen by Nathan Ingleton in 1651, he wrote the event in his diary but the records were destroyed in 1666, in the Great Fire of London. The color of a cloud, as seen from Earth, tells much about what is going on inside the cloud.

In the troposphere, dense, deep clouds exhibit a high reflectance (70% to 95%) throughout the visible spectrum. Tiny particles of water are densely packed and sunlight cannot penetrate far into the cloud before it is reflected out, giving a cloud its characteristic white color, especially when viewed from the top.[41] Cloud droplets tend to scatter light efficiently, so that the intensity of the solar radiation decreases with depth into the gases. As a result, the cloud base can vary from a very light to very-dark-grey depending on the cloud's thickness and how much light is being reflected or transmitted back to the observer. Thin clouds may look white or appear to have acquired the color of their environment or background. High tropospheric clouds appear mostly white if composed entirely of ice crystals and/or supercooled water droplets.

As a tropospheric cloud matures, the dense water droplets may combine to produce larger droplets. If the droplets become too large and heavy to be kept aloft by the air circulation, they will fall from the cloud as rain. By this process of accumulation, the space between droplets becomes increasingly larger, permitting light to penetrate farther into the cloud. If the cloud is sufficiently large and the droplets within are spaced far enough apart, a percentage of the light that enters the cloud is not reflected back out but is absorbed giving the cloud a darker look. A simple example of this is one's being able to see farther in heavy rain than in heavy fog. This process of reflection/absorption is what causes the range of cloud color from white to black.[42]

Other colors occur naturally in tropospheric clouds. Bluish-grey is the result of light scattering within the cloud. In the visible spectrum, blue and green are at the short end of light's visible wavelengths, whereas red and yellow are at the long end. The short rays are more easily scattered by water droplets, and the long rays are more likely to be absorbed. The bluish color is evidence that such scattering is being produced by rain-size droplets in the cloud. A cumulonimbus cloud that appears to have a greenish/bluish tint is a sign that it contains extremely high amounts of water; hail or rain. Supercell type storms are more likely to be characterized by this but any storm can appear this way. Coloration such as this does not directly indicate that it is a severe thunderstorm, it only confirms its potential. Since a green/blue tint signifies copious amounts of water, a strong updraft to support it, high winds from the storm raining out, and wet hail; all elements that improve the chance for it to become severe, can all be inferred from this. In addition, the stronger the updraft is, the more likely the storm is to undergo tornadogenesis and to produce large hail and high winds.[43] Yellowish clouds may occur in the late spring through early fall months during forest fire season. The yellow color is due to the presence of pollutants in the smoke. Yellowish clouds caused by the presence of nitrogen dioxide are sometimes seen in urban areas with high air pollution levels.[44]

Within the troposphere, red, orange, and pink clouds occur almost entirely at sunrise/sunset and are the result of the scattering of sunlight by the atmosphere. When the angle between the sun and the horizon is less than 10 percent, as it is just after sunrise or just prior to sunset, sunlight becomes too red due to refraction for any colors other than those with a reddish hue to be seen.[45] The clouds do not become that color; they are reflecting long and unscattered rays of sunlight, which are predominant at those hours. The effect is much like if one were to shine a red spotlight on a white sheet. In combination with large, mature thunderheads, this can produce blood-red clouds. Clouds look darker in the near-infrared because water absorbs solar radiation at those wavelengths.

In high latitude regions of the stratosphere, nacreous clouds occasionally found there during the polar winter tend to display quite striking displays of mother-of-pearl colorations due to the refraction and diffusion of the sun's rays through thin ice crystal clouds that often contain compounds other than water. At still higher altitudes up in the mesospere, noctilucent clouds sometimes seen in polar regions in the summer usually appear a silvery white that can resemble brightly illuminated cirrus.

Effects on climate

The role of tropospheric clouds in regulating weather and climate remains a leading source of uncertainty in projections of global warming.[46] This uncertainty arises because of the delicate balance of processes related to clouds, spanning scales from millimeters to planetary. Hence, interactions between the large-scale (synoptic meteorology) and clouds becomes difficult to represent in global models. The complexity and diversity of clouds, as outlined above, adds to the problem. On the one hand, white-colored cloud tops promote cooling of Earth's surface by reflecting shortwave radiation from the sun. Most of the sunlight that reaches the ground is absorbed, warming the surface, which emits radiation upward at longer, infrared, wavelengths. At these wavelengths, however, water in the clouds acts as an efficient absorber. The water reacts by radiating, also in the infrared, both upward and downward, and the downward radiation results in a net warming at the surface. This is analogous to the greenhouse effect of greenhouse gases and water vapor.

High tropospheric clouds, such as cirrus, particularly show this duality with both shortwave albedo cooling and longwave greenhouse warming effects that nearly cancel or slightly favor net warming with increasing cloud cover. The shortwave effect is dominant with middle and low clouds like altocumulus and stratocumulus, which results in a net cooling with almost no longwave effect. As a consequence, much research has focused on the response of low clouds to a changing climate. Leading global models can produce quite different results, however, with some showing increasing low-level clouds and others showing decreases.[47][48]

Polar stratospheric and mesospheric clouds are not common or widespread enough to have a significant effect on climate. However an increasing frequency of occurrence of noctilucent clouds since the 19th century may be the result of climate change.[49]

Global brightening

New research indicates a global brightening trend.[50] The details are not fully understood, but much of the global dimming (and subsequent reversal) is thought to be a consequence of changes in aerosol loading in the atmosphere, especially sulfur-based aerosol associated with biomass burning and urban pollution. Changes in aerosol burden can have indirect effects on clouds by changing the droplet size distribution[51] or the lifetime and precipitation characteristics of clouds.[52]

Rainmaking bacteria

Bioprecipitation, the concept of rain-making bacteria, was proposed by David Sands from Montana State University. Such microbes – called ice nucleators – are found in rain, snow, and hail throughout the world. These bacteria may be part of a constant feedback between terrestrial ecosystems and clouds and may even have evolved the ability to promote rainstorms as a means of dispersal. They may rely on the rainfall to spread to new habitats, much as some plants rely on windblown pollen grains.[53][54]

Extraterrestrial

Within our Solar System, any planet or moon with an atmosphere also has clouds. Venus's thick clouds are composed of sulfur dioxide. Mars has high, thin clouds of water ice. Both Jupiter and Saturn have an outer cloud deck composed of ammonia clouds, an intermediate deck of ammonium hydrosulfide clouds and an inner deck of water clouds.[55][56] Saturn's moon Titan has clouds believed to be composed largely of methane.[57] The Cassini–Huygens Saturn mission uncovered evidence of a fluid cycle on Titan, including lakes near the poles and fluvial channels on the surface of the moon. Uranus and Neptune have cloudy atmospheres dominated by water vapor and methane gas.[58][59]

See also

- Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) (in the US)

- Cloud albedo

- Cloud Appreciation Society

- Cloud forcing

- Cloud seeding

- Cloudscape (art)

- Cloudscape photography

- Coalescence

- Extraterrestrial skies

- Flight ceiling

- Fractus cloud

- List of cloud types

- Mist

- Mushroom cloud

- Pileus (meteorology)

- Undulatus asperatus

- Weather lore

- Cloud Computing

References

- ^ a b Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Adiabatic Process". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Dr. Michael Pidwirny (2008). "CHAPTER 8: Introduction to the Hydrosphere (e). Cloud Formation Processes". Physical Geography. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- ^ TE Technology, Inc (2009). "Peltier Cold Plate". Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "Radiational cooling". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

- ^ Robert Fovell (2004). "Approaches to saturation" (PDF). University of California in Los Angeles. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ^ Robert Penrose Pearce (2002). Meteorology at the Millennium. Academic Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-12-548035-2. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ National Weather Service Office, Spokane, Washington (2009). "Virga and Dry Thunderstorms". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bart van den Hurk and Eleanor Blyth (2008). "Global maps of Local Land-Atmosphere coupling" (PDF). KNMI. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ H. Edward Reiley, Carroll L. Shry (2002). Introductory horticulture. Cengage Learning. p. 40. ISBN 9780766815674. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ^ JetStream (2008). "Air Masses". National Weather Service. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ Kirill I︠A︡kovlevich Kondratʹev (2006). Atmospheric aerosol properties: formation, processes and impacts. Springer. p. 403. ISBN 9783540262633.

- ^ Yochanan Kushnir (2000). "The Climate System: General Circulation and Climate Zones". Retrieved 2012-03-13.

- ^ Jack Williams (1997). "Extratropical storms are major weather makers". Retrieved 2012-03-13.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ National Centre for Medium Range Forecasting. Chapter-II Monsoon-2004: Onset, Advancement and Circulation Features. Retrieved on 2008-05-03.

- ^ Dr. Alex DeCaria. Lesson 4 – Seasonal-mean Wind Fields. Retrieved on 2008-05-03.

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Monsoon. Retrieved on 2008-05-03.

- ^ Dr. Owen E. Thompson (1996). Hadley Circulation Cell. Channel Video Productions. Retrieved on 2007-02-11.

- ^ ThinkQuest team 26634 (1999). The Formation of Deserts. Oracle ThinkQuest Education Foundation. Retrieved on 2009-02-16.

- ^ Yochanan Kushnir (2000). "The Climate System: General Circulation and Climate Zones". Retrieved 2012-03-13.

- ^ John D. Cox (2002). Storm Watchers. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 13–17.

- ^ a b c Office National Meteorologique (1932). International Atlas of Clouds and of States of the Sky. Paris. p. II.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Cite error: The named reference "International Meteorological Committee, Commission for the Study of Clouds" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Paul Hancock and Brian Skinner (2000). "clouds. The Oxford Companion to the Earth". Retrieved 2011-02-22.

- ^ Scott, A (2000). "The Pre-Quaternary history of fire". Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology. 164 (1–4): 281. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(00)00192-9.

- ^ National Center for Atmospheric Research (2008). "Hail". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ Ted Fujita (1985). "The Downburst, microburst and macroburst". SMRP Research Paper 210, 122 pp.

- ^ Nilton O. Renno (August 2008). "A thermodynamically general theory for convective vortices" (PDF). Tellus A. 60 (4): 688–99. Bibcode:2008TellA..60..688R. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0870.2008.00331.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q World Meteorological Organization (1995). "WMO cloud classifications" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- ^ a b c d e f JetStream (2010-01-05). "Cloud Classifications". National Weather Service. Retrieved 2011-01-31. Cite error: The named reference "NWS" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d Jim Koermer (2011). "Plymouth State Meteorology Program Cloud Boutique". Plymouth State University. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ^ a b c d e f Clouds Online (2012). "Cloud Atlas". Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- ^ a b Morris (2008). "Clouds - Species and Varieties". Retrieved 2012-02-04.

- ^ Images/images.php.3?img-id=17053 "Cloud Formations off the West Coast of South America". NASA Earth Observatory. Retrieved 2006-05-04.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ a b "cloud: Classification of Clouds". Infoplease.com.

- ^ Becca Hatheway (2009). "Cloud Types". Retrieved 2011-09-15.

- ^ Paul de Valk, Rudolf van Westhrenen, and Cintia Carbajal Henken (2010). "Automated CB and TCU detection using radar and satellite data: from research to application" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-09-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Micheal H. Mogil (2007). Extreme Weather. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publisher. pp. 210–211. ISBN 978-1-57912-743-5.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ National Severe Storms Laboratory (2006-10-15). "A Severe Weather Primer: Questions and Answers about Thunderstorms". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ^ Les Cowley (2011). "Nacreous clouds – Atmospheric optics". Retrieved 2012-01-31.

- ^ Kenneth Chang (2008-09-25). "Caltech Scientist Proposes Explanation for Puzzling Property of Night-Shining Clouds at the Edge of Space". Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- ^ Michael Gadsden and Pekka Parviainen (September 2006). Observing Noctilucent Clouds (PDF). International Association of Geomagnetism & Aeronomy. p. 9. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ^ Increasing Cloud Reflectivity, Royal Geographical Society, 2010

- ^ Clouds absorb more solar radiation than previously thought (blacker than they appear), Chem. Eng. News, 1995, p33

- ^ http://www.meted.ucar.edu/spotter_training/convective/navmenu.php?tab=1&page=2.7.0 © 2011 MetEd/UCAR

- ^ Cities and Air Pollution, Nature, 1998, chapter 10

- ^ Frank W. Gallagher, III. (October 2000). "Distant Green Thunderstorms - Frazer's Theory Revisited". Journal of Applied Meteorology. 39 (10). American Meteorological Society: 1754–1757. Bibcode:2000JApMe..39.1754G. doi:10.1175/1520-0450-39.10.1754.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ D. Randall, R. Wood, S. Bony, R. Colman, T. Fichefet, J. Fyfe, V. Kattsov, A. Pitman, J. Shukla, J. Srinivasan, R. Stouffer, A. Sumi, and K. Taylor. Climate models and their evaluation. In S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K. Averyt, M.Tignor, and H. Miller, editors, Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2007.

- ^ S. Bony and J.-L. Dufresne. Marine boundary layer clouds at the heart of tropical cloud feedback uncertainties in climate models. Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, 10 2005. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2005GL023851.

- ^ B. Medeiros, B. Stevens, I.M. Held, M. Zhao, D.L. Williamson, J.G. Olson, and C.S. Bretherton. Aquaplanets, climate sensitivity, and low clouds. J. Climate, 21(19):4974–4991, 2008.

- ^ Kenneth Chang (2008-09-25). "Caltech Scientist Proposes Explanation for Puzzling Property of Night-Shining Clouds at the Edge of Space". Retrieved 2012-03-13.

- ^ Martin Wild, Hans Gilgen, Andreas Roesch, Atsumu Ohmura, Charles N. Long, Ellsworth G. Dutton, Bruce Forgan, Ain Kallis, Viivi Russak, and Anatoly Tsvetkov. From dimming to brightening: Decadal changes in solar radiation at Earth's surface. Science, 308(5723):847–850, 5 2005. URL http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/308/5723/847.

- ^ S. A. Twomey. Pollution and the planetary albedo. Atmos. Environ., 8:1251–1256, 1974.

- ^ B. Stevens and G. Feingold. Untangling aerosol effects on clouds and precipitation in a buffered system. Nature, 461(7264):607–613, 10 2009.

- ^ Brent Christner (2008-02-28). "LSU scientist finds evidence of 'rain-making' bacteria". American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ^ Christine Dell'Amore (2009-01-12). "Rainmaking Bacteria Ride Clouds to "Colonize" Earth?". National Geographic. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ^ A.P. Ingersoll, T.E. Dowling, P.J. Gierasch, G.S. Orton, P.L. Read, A. Sanchez-Lavega, A.P. Showman, A.A. Simon-Miller, A.R. Vasavada. "Dynamics of Jupiter's Atmosphere" (PDF). Lunar & Planetary Institute. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Monterrey Institute for Research in Astronomy (2006-08-11). "Saturn". Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ^ Athéna Coustenis and F.W. Taylor (2008). Titan: Exploring an Earthlike World. World Scientific. pp. 154–155. ISBN 9789812705013.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.31.090193.001245, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1146/annurev.aa.31.090193.001245instead. - ^ Linda T. Elkins-Tanton (2006). Uranus, Neptune, Pluto, and the Outer Solar System. New York: Chelsea House. pp. 79–83. ISBN 0-8160-5197-6.

Bibliography

- Hamblyn, Richard The Invention of Clouds – How an Amateur Meteorologist Forged the Language of the Skies Picador; Reprint edition (August 3, 2002). ISBN 0312420013

- http://www.ldeo.columbia.edu/news/2006/04_14_06.htm Could Reducing Global Dimming Mean a Hotter, Dryer World?

External links

- BadMeteorology's explanation of why clouds form

- Chitambo Clouds – Clouds and other meteorological phenomena Photographs and info. on different types of clouds.

- Monthly maps of global cloud cover, from NASA's Earth Observatory

- Cloud Appreciation Society Aesthetics of clouds

- A Planetary Order (Terrestrial Cloud Globe)

- Shuttle Views the Earth: Clouds from Space

- Details of main cloud types and sub types

- USA Today Understanding clouds and Fog

- clouds that look as if they were sculpted out of the sky

- Clouds 365 Project Year-long photographic experiment shooting clouds everyday

- Pictures Clouds

- The short film Know Your Clouds (January 1, 1967) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.