Territorial claims in the Arctic: Difference between revisions

Standardising. |

Clarifying. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

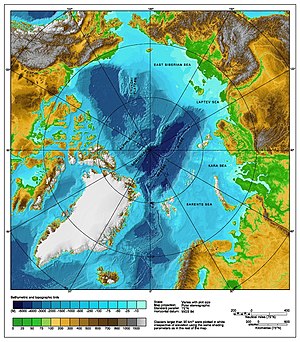

[[Image:IBCAO betamap.jpg|thumb|300px|Arctic topography and bathymetry]] |

[[Image:IBCAO betamap.jpg|thumb|300px|Arctic topography and bathymetry]] |

||

Under international law, no country currently owns the [[North Pole]] or the region of the [[Arctic Ocean]] surrounding it. The five surrounding [[Arctic]] |

Under international law, no country currently owns the [[North Pole]] or the region of the [[Arctic Ocean]] surrounding it. The five surrounding [[Arctic]] countries, [[Russia]], the [[United States]] (via [[Alaska]]), [[Canada]], [[Norway]] and [[Denmark]] (via [[Greenland]]), are limited to an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of {{convert|200|nmi|lk=in}} adjacent to their coasts. |

||

Upon ratification of the [[United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea]] (UNCLOS), a country has a ten year period to make claims to an extended continental shelf which, if validated, gives it exclusive rights to resources on or below the seabed of that extended shelf area.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/annex2.htm|title=United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Annex 2, Article 4)|accessdate=2007-07-26}}</ref> Due to this, Norway (ratified the convention in 1996<ref name="ratif">[http://www.un.org/Depts/los/reference_files/status2007.pdf ]{{dead link|date=January 2012}}</ref>), Russia (ratified in 1997<ref name="ratif"/>), Canada (ratified in 2003<ref name="ratif"/>) and Denmark (ratified in 2004<ref name="ratif"/>) launched projects to provide a basis for seabed claims on extended continental shelves beyond their exclusive economic zones. The United States has signed, but [[United States non-ratification of the UNCLOS|not yet ratified]] this treaty.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.reuters.com/article/latestCrisis/idUSN31335584|publisher=Reuter|title=U.S. Senate panel backs Law of the Sea treaty|last=Drawbaugh|first=Kevin|date=October 31, 2007}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2007/05/20070515-2.html |title=President's Statement on Advancing U.S. Interests in the World's Oceans |publisher=Georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov |date=2007-05-15 |accessdate=2012-01-10}}</ref> |

Upon ratification of the [[United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea]] (UNCLOS), a country has a ten year period to make claims to an extended continental shelf which, if validated, gives it exclusive rights to resources on or below the seabed of that extended shelf area.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/annex2.htm|title=United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Annex 2, Article 4)|accessdate=2007-07-26}}</ref> Due to this, Norway (ratified the convention in 1996<ref name="ratif">[http://www.un.org/Depts/los/reference_files/status2007.pdf ]{{dead link|date=January 2012}}</ref>), Russia (ratified in 1997<ref name="ratif"/>), Canada (ratified in 2003<ref name="ratif"/>) and Denmark (ratified in 2004<ref name="ratif"/>) launched projects to provide a basis for seabed claims on extended continental shelves beyond their exclusive economic zones. The United States has signed, but [[United States non-ratification of the UNCLOS|not yet ratified]] this treaty.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.reuters.com/article/latestCrisis/idUSN31335584|publisher=Reuter|title=U.S. Senate panel backs Law of the Sea treaty|last=Drawbaugh|first=Kevin|date=October 31, 2007}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2007/05/20070515-2.html |title=President's Statement on Advancing U.S. Interests in the World's Oceans |publisher=Georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov |date=2007-05-15 |accessdate=2012-01-10}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 13:13, 26 March 2012

Under international law, no country currently owns the North Pole or the region of the Arctic Ocean surrounding it. The five surrounding Arctic countries, Russia, the United States (via Alaska), Canada, Norway and Denmark (via Greenland), are limited to an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) adjacent to their coasts.

Upon ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a country has a ten year period to make claims to an extended continental shelf which, if validated, gives it exclusive rights to resources on or below the seabed of that extended shelf area.[1] Due to this, Norway (ratified the convention in 1996[2]), Russia (ratified in 1997[2]), Canada (ratified in 2003[2]) and Denmark (ratified in 2004[2]) launched projects to provide a basis for seabed claims on extended continental shelves beyond their exclusive economic zones. The United States has signed, but not yet ratified this treaty.[3][4]

The status of certain portions of the Arctic sea region are in dispute for various reasons. Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia and the United States all regard parts of the Arctic seas as "national waters" (territorial waters out to 12 nautical miles (22 km)) or "internal waters". There also are disputes regarding what passages constitute "international seaways" and rights to passage along them (see Northwest Passage).

North Pole and the Arctic Ocean

National Sectors: 1925–2005

In 1925, based upon the Sector Principle, Canada became the first country to extend its maritime boundaries northward to the North Pole, at least on paper, between 60°W and 141°W longitude, a claim that is not universally recognized (there are in fact 415 nmi (769 km; 478 mi) of ocean between the Pole and Canada's northernmost land point).[5] In 1926 Russia fixed its claim in Soviet law (32°04′35″E to 168°49′30″W).[6] Norway (5°E to 35°E) made similar sector claims — as did the United States (170°W to 141°W), but that sector contained only a few islands so the claim was not pressed. Denmark's sovereignty over all of Greenland was recognized by the United States in 1916 and by an international court in 1933. Denmark could also conceivably claim an Arctic sector (60°W to 10°W).[5]

In the context of the Cold War, Canada sent Inuit families to the far north in the High Arctic relocation, partly to establish territoriality.[7]

In addition, Canada claims the water within the Canadian Arctic Archipelago as its own internal waters. The United States is one of the countries which does not recognize Canada's, or any other countries', Arctic archipelagic water claims, and has allegedly sent nuclear submarines under the ice near Canadian islands without requesting permission.[citation needed]

On April 15, 1926, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR declared the territory between two lines (35°E and 170°W) drawn from Murmansk to the North Pole and from the Chukchi Peninsula to the North Pole to be Soviet territory.[8]

Until 1999, the North Pole and the major part of the Arctic Ocean had been generally considered to comprise international space, including both the waters and the sea bottom. However, both the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea as well as global climate change causing the polar ice to recede at a rate higher than expected due to global warming[citation needed] has prompted several countries to claim or to reinforce pre-existing claims to the waters or seabed of the polar region.

Extended Continental Shelf Claims: 2006–present

Overview

As defined by the UNCLOS, states have ten years from the date of ratification to make claims to an extended continental shelf. On this basis the five states fronting the Arctic Ocean - Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia, and the U.S. - must make and desired claims by 2013, 2014, 2006, and 2007 respectively. Since the U.S. has yet to ratify the UNCLOS, the date for its submission is undetermined at this time.

Claims to extended continental shelves, if deemed valid, give the claimant state exclusive rights to the sea bottom and resources below the bottom. Valid extended continental shelf claims do not and cannot extend a state's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) since the EEZ is determined solely by drawing a 200-nautical-mile (370 km) line using territorial sea baselines as their starting point. This point is made because press reports often confuse the facts and assert that extended continental shelf claims expand a state's EEZ thereby giving a state exclusive rights to not only sea bottom and below resources but also to those in the water column. The Arctic chart prepared by Durham University (see Further Reading reference) clearly illustrates the extent of the uncontested Exclusive Economic Zones of the five states bordering the Arctic Ocean and also the relatively small expanse of remaining "high seas" or totally international waters at the very North of the planet.

Specific nations

Canada

As of July 2001, Canada has not filed an official claim to an extended continental shelf with the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. Canada has through 2013 to file such a claim.

In response to the Russian Arktika 2007 expedition, Canada's Foreign Affairs Minister Peter MacKay said the following:

This is posturing. This is the true north strong and free, and they're fooling themselves if they think dropping a flag on the ocean floor is going to change anything. There is no question over Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic. We've made that very clear. We've established - a long time ago - that these are Canadian waters and this is Canadian property. You can't go around the world these days dropping a flag somewhere. This isn't the 14th or 15th century.

In response to MacKay's comments, Sergey Lavrov, the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, stated:

I read reports of the statements made by my Canadian colleague, Peter MacKay. I know him quite well – it’s very unlike him. I was sincerely astonished by "flag planting." No one engages in flag planting. When pioneers reach a point hitherto unexplored by anybody, it is customary to leave flags there. Such was the case on the Moon, by the way. As to the legal aspect of the matter, we from the outset said that this expedition was part of the big work being carried out under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, within the international authority where Russia’s claim to submerged ridges which we believe to be an extension of our shelf is being considered. We know that this has to be proved. The ground samples that were taken will serve the work to prepare that evidence.[11]

On September 25, 2007, Prime Minister Stephen Harper said, "President Putin assured me that he meant no offense, ... nor any intention to violate any international understanding or any Canadian sovereignty in any way."[12] Prime Minister Harper has also promised to defend Canada's claimed sovereignty by building and operating up to eight Arctic patrol ships, a new army training centre in Resolute Bay, and the refurbishing of an existing deepwater port at a former mining site in Nanisivik.[13]

Denmark

As of July 2001, Denmark has not filed an official claim to an extended continental shelf with the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. Denmark has through 2014 to file a claim.

This section needs to be updated. (May 2011) |

The Danish autonomous province of Greenland has the nearest coastline to the North Pole, and Denmark argues that the Lomonosov Ridge is in fact an extension of Greenland. Danish project included LORITA-1 expedition in April–May 2006[14] and will include tectonic research during LOMROG expedition, included into the 2007-2008 International Polar Year program.[15] This expedition was planned for August–September 2007. It would comprise the Swedish icebreaker Oden and Russian nuclear icebreaker NS 50 Let Pobedy. The latter will lead the expedition through the ice fields to the research location.[16] Documents obtained by the Danish media in mid-2011 revealed that by 2014 Denmark intends to submit a formal claim for sovereignty over the North Pole to the United Nations.[17]

Norway

Norway ratified the UNCLOS in late 1996 and on November 27, 2006, Norway made an official submission into the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (article 76, paragraph 8). There are provided arguments to extend the Norwegian seabed claim beyond the 200 nmi (370 km; 230 mi) EEZ in three areas of the northeastern Atlantic and the Arctic: the "Loop Hole" in the Barents Sea, the Western Nansen Basin in the Arctic Ocean, and the "Banana Hole" in the Norwegian Sea. The submission also states that an additional submission for continental shelf limits in other areas may be posted later.[18]

Russia

Russia ratified the UNCLOS in 1997 and had until 2007 to make its claim to an extended continental shelf.

Russia is claiming a large extended continental shelf as far as the North Pole based on the Lomonosov Ridge within their Arctic sector. Moscow believes the eastern Lomonosov Ridge is an extension of the Siberian continental shelf. The Russian claim does not cross the Russia-US Arctic sector demarcation line, nor does it extend into the Arctic sector of any other Arctic coastal state.

On December 20, 2001, Russia made an official submission into the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (article 76, paragraph 8). In the document it is proposed to establish the outer limits of the continental shelf of Russia beyond the 200-nautical-mile (370 km) Exclusive Economic Zone, but within the Russian Arctic sector.[19] The territory claimed by Russia in the submission is a large portion of the Arctic, extending to the geographic North Pole.[20] One of the arguments was a statement that Lomonosov Ridge, an underwater mountain ridge passing near the Pole, and Mendeleev Ridge are extensions of the Eurasian continent. In 2002 the UN Commission neither rejected nor accepted the Russian proposal, recommending additional research.[19]

On August 2, 2007, a Russian expedition called Arktika 2007, composed of six explorers led by Artur Chilingarov, employing MIR submersibles, for the first time in history descended to the seabed at the North Pole. There they planted the Russian flag and took water and soil samples for analysis, continuing a mission to provide additional evidence related to the Russian claim to the mineral riches of the Arctic.[21] This was part of the ongoing 2007 Russian North Pole expedition within the program of the 2007–2008 International Polar Year.

The expedition aimed to establish that the eastern section of seabed passing close to the pole, known as the Lomonosov Ridge, is in fact an extension of Russia's landmass. The expedition came as several countries are trying to extend their rights over sections of the Arctic Ocean floor. Both Norway and Denmark are carrying out surveys to this end. Vladimir Putin made a speech on a nuclear icebreaker on 3 May 2007, urging greater efforts to secure Russia's "strategic, economic, scientific and defense interests" in the Arctic.[22]

In mid-September 2007, Russia's Natural Resources Ministry issued a statement:

Preliminary results of an analysis of the earth crust model examined by the Arktika 2007 expedition, obtained on September 20, have confirmed that the crust structure of the Lomonosov Ridge corresponds to the world analogues of the continental crust, and it is therefore part of the Russian Federation's adjacent continental shelf.[23]

Viktor Posyolov, an official with Russia's Agency for Management of Mineral Resources:

With a high degree of likelihood, Russia will be able to increase its continental shelf by 1.2 million square kilometers [460,000 square miles] with potential hydrocarbon reserves of not less than 9,000 to 10,000 billion tonnes of conventional fuel beyond the 200-mile (320 km) [322 kilometer] economic zone in the Arctic Ocean[24]

United States of America

As of February 2012, the United States had not ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and, therefore, had not filed an official claim to an extended continental shelf with the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf.

In August 2007, an American Coast Guard icebreaker, the USCGC Healy, headed to the Arctic Ocean to map the sea floor off Alaska. Larry Mayer, director of the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping at the University of New Hampshire, stated the trip had been planned for months, having nothing to do with the Russians planting their flag. The purpose of the mapping work aboard the Healy is to determine the extent of the continental shelf north of Alaska.

Future

It was stated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change on March 25, 2007, that riches are awaiting the shipping industry due to Arctic climate change. This economic sector could be transformed similar to the way the Middle East was by the Suez Canal in the 19th century. There will be a race among nations for oil, fish, diamonds and shipping routes, accelerated by the impact of global warming.[25]

The potential value of the North Pole and the surrounding area resides not so much in shipping itself but in the possibility that lucrative petroleum and natural gas reserves exist below the sea floor. Such reserves are known to exist under the Beaufort Sea. However, the vast majority of the Arctic known to contain gas and oil resources is already within uncontested EEZs. When these current uncontested Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of the Arctic littoral states are taken into account there is only a small unclaimed area at the very top potentially available for open gas/oil exploration.[26]

On September 14, 2007 the European Space Agency reported ice loss had opened up the Northwest Passage "for the first time since records began in 1978", and the extreme loss in 2007 rendered the passage "fully navigable".[27][28] Further exploration for petroleum reserves elsewhere in the Arctic may now become more feasible, and the passage may become a regular channel of international shipping and commerce if Canada is not able to enforce its claim to it.[29]

Foreign Ministers and other officials representing Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia, and the United States met in Ilulissat, Greenland in May 2008, at the Arctic Ocean Conference and announced the Ilulissat Declaration. Among other things the declaration stated that any demarcation issues in the Arctic should be resolved on a bilateral basis between contesting parties.[30][31]

Hans Island

Hans Island is situated in the Nares Strait, a waterway that runs between Ellesmere Island (the northernmost part of Nunavut, Canada) and Greenland. The uninhabited island was named for Greenlandic Arctic traveller Hans Hendrik.

In 1973, Canada and Denmark negotiated the geographic coordinates of the continental shelf, and settled on a delimitation treaty that was ratified by the United Nations on December 17, 1973, and has been in force since March 13, 1974. The treaty lists 127 points (by latitude and longitude) from Davis Strait to the end of Robeson Channel, where Nares Strait runs into Lincoln Sea; the border is defined by geodesic lines between these points. The treaty does not, however, draw a line from point 122 (80° 49' 2 - 66° 29' 0) to point 123 (80° 49' 8 - 66° 26' 3)—a distance of 875 m (0.54 mi). Hans Island is situated in the centre of this area.

Danish flags were planted on Hans Island in 1984, 1988, 1995 and 2003. The Canadian government formally protested these actions. In July 2005, former Canadian defence minister Bill Graham made an unannounced stop on Hans Island during a trip to the Arctic; this launched yet another diplomatic quarrel between the governments, and a truce was called that September.

Canada had claimed Hans Island was clearly in their territory, as topographic maps originally used in 1967 to determine the island's coordinates clearly showed the entire island on Canada's side of the delimitation line. However, federal officials reviewed the latest satellite imagery in July 2007, and conceded that the line went roughly through the middle of the island. This presently leaves ownership of the island disputed, with claims over fishing grounds and future access to the Northwest Passage possibly at stake as well.[32]

Beaufort Sea

There is an ongoing dispute involving a wedge-shaped slice on the International Boundary in the Beaufort Sea, between the Canadian territory of Yukon and the American state of Alaska.[33]

The Canadian position is that the maritime boundary should follow the land boundary. The American position is that the maritime boundary should extend along a path equidistant from the coasts of the two nations. The disputed area may hold significant hydrocarbon reserves. The US has already leased eight plots of terrain below the water to search for and possibly bring to market oil reserves that may exist there. Canada has protested diplomatically in response.[34]

No settlement has been reached to date, because the US has signed but has not ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. If the treaty is ratified, the issue would likely be settled at a tribunal.[33]

On August 20, 2009 United States Secretary of Commerce Gary Locke announced a moratorium on fishing the Beaufort Sea north of Alaska, including the disputed waters.[35][36] Randy Boswell, of Canada.com wrote that the disputed area covered a 21,436 square kilometres (8,276 sq mi) section of the Beaufort Sea (smaller than Israel, larger than El Salvador). He wrote that Canada had filed a "diplomatic note" with the United States in April when the US first announced plans for the moratorium.

Northwest Passage

The legal status of the Northwest Passage is disputed: Canada considers it to be part of its internal waters according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.[37] The United States and most maritime nations,[38] consider them to be an international strait,[39] which means that foreign vessels have right of "transit passage".[40] In such a regime, Canada would have the right to enact fishing and environmental regulation, and fiscal and smuggling laws, as well as laws intended for the safety of shipping, but not the right to close the passage.[41] In addition, the environmental regulations allowed under the UNCLOS are not as robust as those allowed if the Northwest Passage is part of Canada's internal waters.[42]

Arctic territories

- Alaska (United States)

- Aleutian Islands (United States)

- Arkhangelsk Oblast (Russia)

- Bear Island (Norway)

- Canadian Arctic Archipelago

- Chukotka Autonomous District (Russia)

- Diomede Islands (Russia/United States)

- Finnmark (Norway)

- Franz Josef Land (Russia)

- Greenland (Denmark)

- Iceland (majority of island south of Arctic Circle)

- Jan Mayen (Norway)

- Krasnoyarsk Territory (majority of territory south of the Arctic Circle) (Russia)

- Labrador, (part of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada)

- Murmansk Oblast (Russia)

- Nenets Autonomous District (Russia)

- New Siberian Islands (Russia)

- Northwest Territories (Canada)

- Novaya Zemlya (Russia)

- Nunavik (northern Québec, Canada)

- Nunavut (Canada)

- Russian Arctic islands

- Sápmi (Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia)

- Sakha Republic (Yakutia) (most of the Republic south of the Arctic Circle) (Russia)

- Severnaya Zemlya (Russia)

- Siberia (Russia)

- Svalbard (Norway)

- Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District (Russia)

- Yukon (Canada)

- Wrangel Island (Russia)

See also

- United States Outer Continental Shelf

- Outer Continental Shelf (in geography)

- List of Russian explorers

- Arctic policy of Russia

- Arctic Cooperation and Politics

- Canada – United States relations#Arctic disputes

- Continental shelf of Russia

- Territorial claims in Antarctica

References

- ^ "United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Annex 2, Article 4)". Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- ^ a b c d [1][dead link]

- ^ Drawbaugh, Kevin (October 31, 2007). "U.S. Senate panel backs Law of the Sea treaty". Reuter.

- ^ "President's Statement on Advancing U.S. Interests in the World's Oceans". Georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov. 2007-05-15. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ a b T. E. M. McKitterick, "The Validity of Territorial and Other Claims in Polar Regions," Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law, 3rd Ser., Vol. 21, No. 1. (1939), pp. 89-97.[2]

- ^ Sobranie Zakonov SSSR, 1926 (Russian)

- ^ Dussault, René; Erasmus, George (1994). "The High Arctic Relocation- A Report on the 1953–55 Relocation (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples)". Canadian Government Publishing. p. 190.

- ^ George Ginsburgs, The Soviet Union and International Cooperation in Legal Matters, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1988, ISBN 0-7923-3094-3, available at Google Print

- ^ Reynolds, Paul (2008-05-29). "Trying to head off an Arctic 'gold rush'". BBC News. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "Russia plants flag staking claim to Arctic region". Cbc.ca. 2007-08-02. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "Transcript of Remarks and Replies to Media Questions by Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov at Joint Press Conference with Philippine Foreign Affairs Secretary A". Mid.ru. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "A Conversation with Stephen Harper [Rush Transcript; Federal News Service] - Council on Foreign Relations". Cfr.org. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "Harper announces northern deep-sea port, training site". CBC News. 2007-08-11.

- ^ Kontinentalsokkelprojektet. "LORITA-1 (Lomonosov Ridge Test of Appurtenance)". A76.dk. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "LOMROG - Lomonosov Ridge off Greenland". Geo.su.se. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ Kontinentalsokkelprojektet. "LOMROG 2007 cruise with the Swedish icebreaker Oden north of Greenland". A76.dk. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "Denmark plans to claim North Pole". The Boston Globe. Copenhagen. Associated Press. 18 May 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

The draft document titled 'Strategy for the Arctic' said Denmark's Science Ministry has started collecting data to formally submit a claim for those areas to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf no later than 2014.

- ^ Outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles (370 km) from the baselines: Submissions to the Commission: Submission by Norway CLCS. United Nations

- ^ a b Outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles (370 km) from the baselines: Submissions to the Commission: Submission by the Russian Federation CLCS. United Nations

- ^ Area of the continental shelf of the Russian Federation in the Arctic Ocean beyond 200-nautical-mile zone - borders of the 200 nmi (370 km; 230 mi) zone are marked in red, territory claimed by Russia is shaded

- ^ The Battle for the Next Energy Frontier: The Russian Polar Expedition and the Future of Arctic Hydrocarbons, by Shamil Midkhatovich Yenikeyeff and Timothy Fenton Krysiek, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, August 2007

- ^ ITAR-TASS (English) 0602 GMT 03 May 2009

- ^ "Lomonosov Ridge, Mendeleyev elevation part of Russia's shelf - report". Interfax Moscow. 2007-09-20. Retrieved 2007-09-21. [dead link]

- ^ "Russia's Arctic Claim Backed By Rocks, Officials Say". News.nationalgeographic.com. 2010-10-28. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ The Big Melt, The New York Times, October 2005

- ^ http://www.dur.ac.uk/resources/ibru/arctic.pdf

- ^ "Satellites witness lowest Arctic ice coverage in history". Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- ^ "Warming 'opens Northwest Passage'". BBC News. 2007-09-14. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- ^ "The Scramble for the Arctic: The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas and Extending Seabed Claims". Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association 67th Annual National Conference, The Palmer House Hilton, Chicago, IL Online. 2009-04-02. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- ^ "Conference in Ilulissat, Greenland: Landmark political declaration on the future of the Arctic". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark. 2008-05-28. Archived from the original on 2008-06-15. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- ^ "The Ilulissat Declaration" (PDF). um.dk. 2008-05-28. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- ^ "Satellite imagery moves Hans Island boundary: report". Canadian Press. July 26, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ a b "Transnational Issues CIA World Fact Book". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ Sea Changes[dead link]

- ^ "Secretary of Commerce approves fisheries plan for ArcticSecretary of Commerce approves fisheries plan for Arctic". World of fishing. 2009-08-20. Archived from the original on 2009-09-15.

- ^ Randy Boswell (2009-09-04). "Canada protests U.S. Arctic fishing ban". Canada.com. Archived from the original on 2009-09-15.

- ^ Todd P. Kenyon. "Unclos Part Iv, Archipelagic States". Admiraltylawguide.com. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ Northwest Passage gets political name change - Ottawa Citizen

- ^ Climate Change and Canadian Sovereignty in the Northwest Passage

- ^ The Northwest Passage Thawed[dead link]

- ^ Todd P. Kenyon. "Unclos Part Iii, Straits Used For International Navigation". Admiraltylawguide.com. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "The Northwest Passage and Climate Change from the Library of Parliament - Canadian Arctic Sovereignty". Parl.gc.ca. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

External links

- "Arctic Map shows dispute hotspots". BBC. 2008-08-05.

- "Maritime jurisdiction and boundaries in the Arctic region" (PDF). International Boundaries Research Unit, Durham University. 2008-07-24.

- "Arctic Sovereignty Policy Review" (PDF). Carleton University School of Journalism & Communication. 2011.

- International territorial disputes of the United States

- Territorial disputes of Canada

- Territorial disputes of Denmark

- Territorial disputes of Norway

- Territorial disputes of Russia

- Multilateral relations of Russia

- Government of the Arctic

- Arctic

- Canada–Russia relations

- Canada–United States relations

- Russia–United States relations