Frankenstein: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

Cleric2145 (talk | contribs) Good faith revert of edit(s) by 24.8.2.235 using STiki Please undo revert if info is correct |

|||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

The creature has often been mistakenly called "Frankenstein". In 1908 one author said "It is strange to note how well-nigh universally the term "Frankenstein" is misused, even by intelligent people, as describing some hideous monster...".<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=rBoOAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA238 ''Author's Digest: The World's Great Stories in Brief''], by Rossiter Johnson, 1908</ref> [[Edith Wharton]]'s ''The Reef'' (1916) describes an unruly child as an "infant Frankenstein."<ref>''[[The Reef (novel)|The Reef]]'', page 96.</ref> David Lindsay's "The Bridal Ornament", published in ''The Rover'', 12 June 1844, mentioned "the maker of poor Frankenstein." After the release of [[James Whale]]'s popular 1931 film ''[[Frankenstein (1931 film)|Frankenstein]]'', the public at large began speaking of the monster itself as "Frankenstein". A reference to this occurs in ''[[Bride of Frankenstein]]'' (1935) and in several subsequent films in the series, as well as in film titles such as ''[[Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein]]''. |

The creature has often been mistakenly called "Frankenstein". In 1908 one author said "It is strange to note how well-nigh universally the term "Frankenstein" is misused, even by intelligent people, as describing some hideous monster...".<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=rBoOAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA238 ''Author's Digest: The World's Great Stories in Brief''], by Rossiter Johnson, 1908</ref> [[Edith Wharton]]'s ''The Reef'' (1916) describes an unruly child as an "infant Frankenstein."<ref>''[[The Reef (novel)|The Reef]]'', page 96.</ref> David Lindsay's "The Bridal Ornament", published in ''The Rover'', 12 June 1844, mentioned "the maker of poor Frankenstein." After the release of [[James Whale]]'s popular 1931 film ''[[Frankenstein (1931 film)|Frankenstein]]'', the public at large began speaking of the monster itself as "Frankenstein". A reference to this occurs in ''[[Bride of Frankenstein]]'' (1935) and in several subsequent films in the series, as well as in film titles such as ''[[Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein]]''. |

||

Often times people mistakenly refer to the monster as Frankenstein. He is supposed to be reffred to as the monster, or Frankensteins monster. |

|||

===Victor Frankenstein's surname=== |

===Victor Frankenstein's surname=== |

||

Revision as of 21:04, 28 April 2012

| File:Frank1818.jpg Volume I, first edition | |

| Author | Mary Shelley |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Horror, Gothic, Romance, science fiction |

| Publisher | Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mavor & Jones |

Publication date | 1 January 1818 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Pages | 280 |

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is a novel written by Mary Shelley about a monster produced by an unorthodox scientific experiment. Shelley started writing the story when she was eighteen, and the novel was published when she was twenty-one. The first edition was published anonymously in London in 1818. Shelley's name appears on the second edition, published in France in 1823.

Shelley had travelled the region in which the story takes place, and the topics of galvanism and other similar occult ideas were themes of conversation among her companions, particularly her future husband, Percy. The storyline emerged from a dream. Mary, Percy, Lord Byron, and John Polidori decided to have a competition to see who could write the best horror story. After thinking for weeks about what her possible storyline could be, Shelley dreamt about a scientist who created life and was horrified by what he had made. She then wrote Frankenstein.

Frankenstein is infused with some elements of the Gothic novel and the Romantic movement and is also considered to be one of the earliest examples of science fiction. Brian Aldiss has argued that it should be considered the first true science fiction story, because unlike in previous stories with fantastical elements resembling those of later science fiction, the central character "makes a deliberate decision" and "turns to modern experiments in the laboratory" to achieve fantastic results.[1] The story is partially based on Giovanni Aldini's electrical experiments on dead and (sometimes) living animals and was also a warning against the expansion of modern humans in the Industrial Revolution, alluded to in its subtitle, The Modern Prometheus. It has had a considerable influence across literature and popular culture and spawned a complete genre of horror stories and films.

Since publication of the novel, the name "Frankenstein" is often used to refer to the monster itself, as is done in the stage adaptation by Peggy Webling. This usage is sometimes considered erroneous, but usage commentators regard the monster sense of "Frankenstein" as well-established and not an error[2][3][4]. In the novel, the monster is identified via words such as "creature," "monster", "fiend", "wretch", "vile insect", "daemon", and "it". The monster refers to himself speaking to Dr. Frankenstein as "the Adam of your labors", and elsewhere as someone who "would have" been "your Adam", but is instead your "fallen angel."

Summary

In Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein, the reader is addressed by several storytellers whose perspectives on the issues at hand vary by their personal involvement and bias, leaving the reader to become yet another lens through which the truth of the matter must be filtered in order to reveal reliable material. Frankenstein is written in the form of a frame story that starts with Captain Robert Walton writing letters to his sister.

Captain Walton's introductory frame narrative

The novel Frankenstein is written in epistolary form, documenting a correspondence between Captain Robert Walton and his sister, Margaret Walton Saville. Walton is a failed writer who sets out to explore the North Pole and expand his scientific knowledge in hopes of achieving fame. The ship then becomes trapped in ice, and, one day, the crew sees a dog sled in the distance, where there is an indistinct feature of a large man. A few hours later, the crew finds a nearly frozen and emaciated man named Victor Frankenstein, who is in desperate need of sustenance. Frankenstein has been in pursuit of the gigantic man observed by Walton's crew until almost all of his dogs except one died. He has broken apart his dog sled to make oars and rowed an ice-raft toward the vessel. Frankenstein starts to recover from his exertion and then recounts a story of his life's miseries to Walton. He explains how his obsession for wisdom led him to this predicament. Before he begins his narrative, he makes Walton promise to capture the monster. In telling his story to the captain, he finds peace within himself.

Victor Frankenstein's narrative

Victor begins by telling of his childhood. Born into a wealthy family in Geneva, he is encouraged to seek a greater understanding of the world around him through science. He grows up in a safe environment, surrounded by loving family and friends. When he is around 4 years old, his parents adopt Elizabeth Lavenza, an orphan whose mother has just died. (She is their niece and Victor's cousin in the first edition, but this is not established in the second edition.) Victor has a possessive infatuation with Elizabeth. He has two younger brothers: Ernest and William, the latter seventeen years younger than he. Ernest however, was six years younger than Victor.

As a young boy, Victor is obsessed with studying outdated theories of science that focus on achieving natural wonders, at times to his father's disdain. In particular, he studies the works of Cornelius Agrippa, Paracelsus and Albertus Magnus. He plans to attend the University of Ingolstadt in Germany. A week before his planned departure, his mother dies, after nursing his beloved Elizabeth, who has been ill with scarlet fever. The whole family is aggrieved, and Frankenstein sees the mother's death as his life's first misfortune. At university, he excels at chemistry and other sciences, and, after studying galvanism, a phenomenon discovered in the 1790s, develops a secret technique to imbue inanimate bodies with life.

While the exact details of the monster's construction are left ambiguous, Victor explains "I collected bones from charnel-houses and disturbed, with profane fingers, the tremendous secrets of the human frame."[5] Another statement, "The dissecting-room and the slaughter-house furnished many of my materials", suggests that some elements of Frankenstein's creation may not be from human bodies. This is further corroborated by a passage referring to his work in the "unhallowed damps of the grave." Frankenstein finds himself forced to make the creature much larger than a normal man — he estimates it to be about eight feet tall — because of the difficulty in replicating the minute parts of the human body. His creation, which he has hoped would be beautiful, is instead hideous to his eyes, with dull yellow eyes, and a withered, translucent, yellowish skin that barely conceals the muscular system and blood vessels. After bringing his creation to life, Victor is repulsed by his work: "I had desired it with an ardour that far exceeded moderation; but now that I had finished, the beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart."[6] Victor didn't think about the value of life and played GOD. His desire of creating life was merely selfish. Victor flees, hoping to forget what he has created, and attempts to live a normal life. His abandonment leaves the monster confused, angry, and afraid.

After his quiet, secretive and exhausting efforts to create a living human being, Victor becomes ill. His illness could be drawn out from his guilt of abandoning his creation. He is nursed back to health by his childhood friend, Henry Clerval. It takes him four months to recover from his illness. He determines that he should return home when his nine-year-old brother, William, is found murdered. Elizabeth blames herself for William's death because she has allowed him to have access to his mother's locket, which she believes has caused a thief to murder William and steal the locket. William's nanny, Justine, is hanged for the murder based on the discovery of Victor's mother's locket in her pocket, and her confessing out of fear of not receiving absolution from a priest, though she regrets it. The locket was later revealed to have been placed there by Victor's creation.

When Victor learns of his brother's death, he returns to Geneva to be with his family. He sees the monster in the woods where his brother has been murdered, and becomes certain that his monster is the killer. Ravaged by his grief and self-reproach to have created the being that has caused so much destruction, he retreats into the mountains to find peace. After some time in solitude, the monster approaches him. Initially furious and intent on killing the creature, Victor attempts to attack it.

The monster, far larger and more agile than its creator, eludes him and allows him to compose himself. Intelligent and articulate, it tells Victor of its encounters with people, and how it had become afraid of them and spent a year living near a cottage, observing the De Lacey family living there. The De Laceys had originally been wealthy, but have been forced into exile when Felix De Lacey rescued the father of his beloved, an Arabian girl named Safie. This man, a Turkish merchant who was wrongfully accused of a crime and sentenced to death, once rescued, agreed to allow Felix to marry Safie. Ultimately, though, he was unable to stand the idea of his daughter marrying a Christian and fled with her. Safie has returned to Switzerland, to be with her love Felix DeLacey, and eager for the freedom of European women.

Through observing the De Lacey family, the monster has become educated and self-aware. It had also discovered a lost satchel of books and learned to read. Seeing its reflection in a pool, it realized that its physical appearance is hideous compared to the humans it watches. The monster compares itself to Lucifer from Paradise Lost, one of the books it has read. In its loneliness, it sought to befriend the De Laceys. It presented itself first to the aged father of the family, who is blind and cannot see its deformity, and was received with kindness and hospitality. Unfortunately, the others of the family were horrified by its appearance and reacted viciously out of fear, with violence against it. Because of this interaction, the De Laceys fled their home. The Creature in a fit of rage torches the house and watches as it burns to the ground. This is the Creature's first act of destruction.

In its travels some time later, the monster saw a young girl tumble into a stream and rescued her from drowning. A man, seeing it with the child in its arms, pursued it and fired a gun, wounding it. The monster has now sworn to have vengeance on all humanity, and especially on its creator.

The monster, traveling to Geneva, met a little boy — Victor's brother William — in the woods outside the town of Plainpalais. It hoped that the child would be a companion for it, because he appeared to potentially be unaffected by the perception older people had of its hideousness. So it planned to abduct him: "Boy, you will never see your father again; you must come with me." Horrified, the boy shouted insults and revealed himself as a Frankenstein: "Hideous monster! let me go. My papa is a syndic - - he is M. Frankenstein - he will punish you. You dare not keep me." The creature grabbed the boy by the throat to silence him. When it discovered that it had accidentally strangled its victim, it took this as its first act of vengeance against its creator. It removed a locket from the boy's body and placed it in the folds of the dress of a young woman — William's nanny, Justine — who had been sleeping in a barn nearby, assuming she would be accused of the murder. Frankenstein is present at Justine's trial and even speaks on her behalf but he knows that he is responsible for William's death, because the monster is his creation. But he is too afraid to confess about the Creature out of fear that everyone will think he is crazy, so Justine is found guilty and is wrongly executed.

The monster concludes its story with a demand that Frankenstein create for it a female companion like itself, on the basis that it is lonely since nobody will accept it. It argues that as a living thing, it has a right to happiness and that Victor, as its creator, has a duty to obey it. It promises that if Victor grants its request, it and its mate will vanish into the wilderness of South America uninhabited by man, never to reappear. Victor at first refuses, but the monster replies with the demand, "You are my creator, but I am your master. Obey!"

Fearing for his family, Victor reluctantly agrees and travels to England to do his work. He is accompanied by Clerval, but they separate in Scotland. Through their travels, Victor suspects that the monster is following him. Working on a second being on the Orkney Islands, he is plagued by premonitions of what his work might wreak, particularly as creating a mate for the creature might lead to an entire race of monsters that could plague mankind for millennia to come. He destroys the unfinished example after he sees the monster looking through the window. The monster witnesses this and, confronting Victor, vows that it will have its revenge on Victor's upcoming wedding night. Victor sails far out to sea to dispose of the parts of the unfinished example, and remains adrift and alone. Meanwhile, the monster murders Clerval and leaves the corpse on an Irish beach, coincidentally near where Victor finds himself washed up after an unintentionally long voyage. Arriving in Ireland, Victor is imprisoned for the murder of Clerval, and becomes seriously ill, suffering another mental breakdown in prison. After being acquitted, and with his health renewed, he returns home with his father.

Once home, Victor marries his cousin Elizabeth and prepares for a fight to the death with the monster. Wrongly believing the monster's vowed revenge meant his own death, he asks Elizabeth to retire to her room for the night while he goes looking for the fiend. He searches the house and grounds, but doesn't find it. The enemy murders the secluded Elizabeth — as Victor has destroyed its mate — instead. Victor sees the monster at the window pointing at the corpse. Grief-stricken by the deaths of William, Justine, Clerval, and now Elizabeth, Victor's father dies. Victor vows to pursue the monster until one of them annihilates the other. After months of pursuit, the two end up in the Arctic Circle, near the North Pole.

Captain Walton's concluding frame narrative

At the end of Victor's narrative, Captain Walton resumes the telling of the story. A few days after the vanishing of the creature, the ship becomes entombed in ice and Walton's crew insists on returning south once they are freed. In spite of a passionate speech from Frankenstein, encouraging the crew to push further north, Walton realizes that he must relent to his men's demands and agrees to head for home. Frankenstein dies shortly thereafter, and Walton discovers the monster on his ship, mourning over Frankenstein's body. Walton hears the monster's adamant justification for its vengeance as well as expressions of remorse. Frankenstein's death has not brought it peace. Rather, its crimes have increased its misery and alienation; it has found only its own emotional ruin in the destruction of its creator. It vows to exterminate itself on its own funeral pyre so that no others will ever know of its existence. Walton watches as it drifts away on an ice raft that is soon lost in darkness.

Composition

How I, then a young girl, came to think of, and to dilate upon, so very hideous an idea?[7]

During the rainy summer of 1816, the "Year Without a Summer", the world was locked in a long cold volcanic winter caused by the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815.[8] Mary Shelley, aged 18, and her lover (and later husband) Percy Bysshe Shelley, visited Lord Byron at the Villa Diodati by Lake Geneva in Switzerland. The weather was consistently too cold and dreary that summer to enjoy the outdoor holiday activities they had planned, so the group retired indoors until dawn.

Among other subjects, the conversation turned to galvanism and the feasibility of returning a corpse or assembled body parts to life, and to the experiments of the 18th-century natural philosopher and poet Erasmus Darwin, who was said to have animated dead matter.[9] Sitting around a log fire at Byron's villa, the company also amused themselves by reading German ghost stories, prompting Byron to suggest they each write their own supernatural tale. Shortly afterward, in a waking dream, Mary Shelley conceived the idea for Frankenstein:

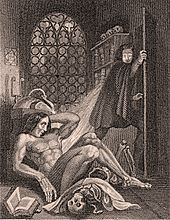

I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for SUPREMELY frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world.[10]

She began writing what she assumed would be a short story. With Percy Shelley's encouragement, she expanded this tale into a full-fledged novel.[11] She later described that summer in Switzerland as the moment "when I first stepped out from childhood into life".[12] Shelley wrote the first four chapters in the weeks following the suicide of her half-sister Fanny.[13] Byron managed to write just a fragment based on the vampire legends he heard while travelling the Balkans, and from this John Polidori created The Vampyre (1819), the progenitor of the romantic vampire literary genre. Thus, two legendary horror tales originated from this one circumstance.

The group talked about Enlightenment and Counter-Enlightenment ideas as well. Shelley believed the Enlightenment idea that society could progress and grow if political leaders used their powers responsibly; however, she also believed the Romantic ideal that misused power could destroy society (Bennett 36-42).[14]

Mary's and Percy Bysshe Shelley's manuscripts for the first three-volume edition in 1818 (written 1816–1817), as well as Mary Shelley's fair copy for her publisher, are now housed in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The Bodleian acquired the papers in 2004, and they belong now to the Abinger Collection.[15] On 1 October 2008, the Bodleian published a new edition of Frankenstein which contains comparisons of Mary Shelley's original text with Percy Shelley's additions and interventions alongside. The new edition is edited by Charles E. Robinson: The Original Frankenstein (ISBN 978-1851243969).[16]

In September 2011 the astronomer Donald Olson, inspecting data about the motion of the moon and stars, concluded that the original conversation, and the waking dream, took place on the night of 16 June 1816.[17]

Publication

Mary Shelley completed her writing in May 1817, and Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was first published on 1 January 1818 by the small London publishing house of Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mavor, & Jones.[18][19] It was issued anonymously, with a preface written for Mary by Percy Bysshe Shelley and with a dedication to philosopher William Godwin, her father. It was published in an edition of just 500 copies in three volumes, the standard "triple-decker" format for 19th century first editions. The novel had been previously rejected by Percy Bysshe Shelley's publisher, Charles Ollier and by Byron's publisher John Murray.[citation needed]

The second edition of Frankenstein was published on 11 August 1823 in two volumes (by G. and W. B. Whittaker) following the success of the stage play Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein by Richard Brinsley Peake;[20] this edition credited Mary Shelley as the author.

On 31 October 1831, the first "popular" edition in one volume appeared, published by Henry Colburn & Richard Bentley.[21] This edition was heavily revised by Mary Shelley, partially because of pressure to make the story more conservative, and included a new, longer preface by her, presenting a somewhat embellished version of the genesis of the story. This edition tends to be the one most widely read now, although editions containing the original 1818 text are still published.[22] Many scholars prefer the 1818 text, arguing that it preserves the spirit of Shelley's original publication (see Anne K. Mellor's "Choosing a Text of Frankenstein to Teach" in the W.W. Norton Critical edition).

Name origins

The monster

Part of Frankenstein's rejection of his creation is the fact that he does not give it a name, which gives it a lack of identity. Instead it is referred to by words such as "monster", "demon", "devil", "fiend", "wretch" and "it". When Frankenstein converses with the monster in Chapter 10, he addresses it as "vile insect", "abhorred monster", "fiend", "wretched devil" and "abhorred devil".

During a telling of Frankenstein, Shelley referred to the creature as "Adam".[24] Shelley was referring to the first man in the Garden of Eden, as in her epigraph:

- Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay

- To mould Me man? Did I solicit thee

- From darkness to promote me?

- John Milton, Paradise Lost (X.743–5)

The creature has often been mistakenly called "Frankenstein". In 1908 one author said "It is strange to note how well-nigh universally the term "Frankenstein" is misused, even by intelligent people, as describing some hideous monster...".[25] Edith Wharton's The Reef (1916) describes an unruly child as an "infant Frankenstein."[26] David Lindsay's "The Bridal Ornament", published in The Rover, 12 June 1844, mentioned "the maker of poor Frankenstein." After the release of James Whale's popular 1931 film Frankenstein, the public at large began speaking of the monster itself as "Frankenstein". A reference to this occurs in Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and in several subsequent films in the series, as well as in film titles such as Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein.

Victor Frankenstein's surname

Mary Shelley maintained that she derived the name "Frankenstein" from a dream-vision. Despite her public claims of originality, the significance of the name has been a source of speculation. Literally, in German, the name Frankenstein means "stone of the Franks, Franks' stone." The name is associated with various places in Germany, such as Castle Frankenstein (Burg Frankenstein) in Mühltal, Hesse, or Castle Frankenstein in Frankenstein, Palatinate. There is also a castle called Frankenstein in Bad Salzungen, Thuringia. Furthermore, there is a municipality called Frankenstein in Saxony, and before 1946, Ząbkowice Śląskie, a city in Silesia, Poland, was known as Frankenstein in Schlesien.

More recently, Radu Florescu, in his book In Search of Frankenstein, argued that Mary and Percy Shelley visited Castle Frankenstein on their way to Switzerland, near Darmstadt along the Rhine, where a notorious alchemist named Konrad Dippel had experimented with human bodies, but that Mary suppressed mentioning this visit, to maintain her public claim of originality. A recent literary essay[27] by A.J. Day supports Florescu's position that Mary Shelley knew of, and visited Castle Frankenstein[28] before writing her debut novel. Day includes details of an alleged description of the Frankenstein castle that exists in Mary Shelley's 'lost' journals. However, this theory is not without critics; Frankenstein expert Leonard Wolf calls it an "unconvincing...conspiracy theory."[29] According to Jörg Heléne, the 'lost journals' as well as Florescu's claims could not be verified.[30]

Victor Frankenstein's given name

A possible interpretation of the name Victor derives from Paradise Lost by John Milton, a great influence on Shelley (a quotation from Paradise Lost is on the opening page of Frankenstein and Shelley even allows the monster himself to read it).[31][32] Milton frequently refers to God as "the Victor" in Paradise Lost, and Shelley sees Victor as playing God by creating life. In addition to this, Shelley's portrayal of the monster owes much to the character of Satan in Paradise Lost; indeed, the monster says, after reading the epic poem, that he empathises with Satan's role in the story.

There are many similarities between Victor and Percy Shelley, Mary's husband. Victor was a pen name of Percy Shelley's, as in the collection of poetry he wrote with his sister Elizabeth, Original Poetry by Victor and Cazire.[33] There is speculation that one of Mary Shelley's models for Victor Frankenstein was Percy, who at Eton had "experimented with electricity and magnetism as well as with gunpowder and numerous chemical reactions", and whose rooms at Oxford were filled with scientific equipment.[34] Percy Shelley was the first-born son of a wealthy country squire with strong political connections and a descendant of Sir Bysshe Shelley, 1st Baronet of Castle Goring, and Richard Fitzalan, 10th Earl of Arundel.[35] Victor's family is one of the most distinguished of that republic and his ancestors were counsellors and syndics. Percy had a sister named Elizabeth. Victor had an adopted sister, named Elizabeth. On 22 February 1815, Mary Shelley delivered a two-month premature baby and the baby died two weeks later. Percy did not care about the condition of this premature infant and left with Claire, Mary's stepsister, for a lurid affair.[36] When Victor saw the creature come to life he fled the apartment, though the newborn creature approached him, as a child would a parent. The question of Victor's responsibility to the creature is one of the main themes of the book.

Modern Prometheus

The Modern Prometheus is the novel's subtitle (though some modern publishings of the work now drop the subtitle, mentioning it only in an introduction). Prometheus, in later versions of Greek mythology, was the Titan who created mankind. A task given to him by Zeus, he was to create a being with clay and water in the image of the gods that could have a spirit breathed into it.[37] Prometheus taught man to hunt, read, and heal their sick, but after he tricked Zeus into accepting poor-quality offerings from humans, Zeus kept fire from mankind. Prometheus being the creator, took back the fire from Zeus to give to man. When Zeus discovered this, he sentenced Prometheus to be eternally punished by fixing him to a rock of Caucasus, where each day an eagle would peck out his liver, only for the liver to regrow the next day because of his immortality as a god. He was intended to suffer alone for all of eternity, but eventually Heracles (Hercules) released him.

Prometheus was also a myth told in Latin but was a very different story. In this version Prometheus makes man from clay and water, again a very relevant theme to Frankenstein as Victor rebels against the laws of nature (how life is naturally made) and as a result is punished by his creation.

The Titan in the Greek mythology of Prometheus parallels Victor Frankenstein. Victor's work by creating man by new means reflects the same innovative work of the Titan in creating humans. Victor, in a way, stole the secret of creation from God just as the Titan stole fire from heaven to give to man. Both the Titan and Victor are punished for their actions. Victor is reprimanded by suffering the loss of those close to him and the dread of being killed himself by his creation. That situation could have possibly been resolved early on by Victor letting his creation into his life. It seemed that his family had the potential for taking the monster in and making him a part of their lives.

Some have claimed that for Mary Shelley, Prometheus was not a hero but rather something of a devil, whom she blamed for bringing fire to man and thereby seducing the human race to the vice of eating meat (fire brought cooking which brought hunting and killing).[38] Support for this claim may be reflected in Chapter 17 of the novel, where the "monster" speaks to Victor Frankenstein: "My food is not that of man; I do not destroy the lamb and the kid to glut my appetite; acorns and berries afford me sufficient nourishment." For Romantic Era artists in general, Prometheus' gift to man echoed the two great utopian promises of the 18th century: the Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution, containing both great promise and potentially unknown horrors.

Byron was particularly attached to the play Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus, and Percy Shelley would soon write his own Prometheus Unbound (1820). The term "Modern Prometheus" was actually coined by Immanuel Kant, referring to Benjamin Franklin and his then recent experiments with electricity.[39]

Shelley's sources

Shelley incorporated a number of different sources into her work, one of which was the Promethean myth from Ovid. The influence of John Milton's Paradise Lost, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, are also clearly evident within the novel. Also, both Shelleys had read William Thomas Beckford's Gothic novel Vathek.[citation needed] Frankenstein also contains multiple references to her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, and her major work A Vindication of the Rights of Woman which discusses the lack of equal education for males and females. The inclusion of her mother's ideas in her work is also related to the theme of creation and motherhood in the novel. Mary is likely to have acquired some ideas for Frankenstein's character from Humphry Davy's book Elements of Chemical Philosophy in which he had written that "science has...bestowed upon man powers which may be called creative; which have enabled him to change and modify the beings around him...". References to the French Revolution run through the novel; a possible source may lie in François-Félix Nogaret's Le Miroir des événemens actuels, ou la Belle au plus offrant (1790): a political parable about scientific progress featuring an inventor named Frankénsteïn who creates a life-sized automaton.[40]

Reception

Initial critical reception of the book mostly was unfavourable, compounded by confused speculation as to the identity of the author. Sir Walter Scott wrote that "upon the whole, the work impresses us with a high idea of the author's original genius and happy power of expression", but most reviewers thought it "a tissue of horrible and disgusting absurdity" (Quarterly Review).

Mary Shelly had contact with some of the most influential minds of her time. Shelly's father was very progressive and encouraged his daughter to participate in the conversations that took place in his home with various scientific minds, many of whom were active engaged in the study of anatomy. She was familiar with the ideas of using dead bodies for study, the newer practice of using electricity to animate the dead, and the concerns of religion and the general public in regard to the morality of tampering with God's work. Today there are actual scientific breakthroughs inspired by Frankenstein like devices that amplify the electric impulses from one's brain and reanimate paralyzed limbs of stroke victims and paraplegics. So, in the end, the ideas Shelly portrays are very feasible and not absurd at all.

Despite the reviews, Frankenstein achieved an almost immediate popular success. It became widely known especially through melodramatic theatrical adaptations — Mary Shelley saw a production of Presumption; or The Fate of Frankenstein, a play by Richard Brinsley Peake, in 1823. A French translation appeared as early as 1821 (Frankenstein: ou le Prométhée Moderne, translated by Jules Saladin).

Frankenstein has been both well-received and disregarded since its anonymous publication in 1818. Critical reviews of that time demonstrate these two views. The Belle Assemblee described the novel as "very bold fiction" (139). The Quarterly Review stated "that the author has the power of both conception and language" (185). Sir Walter Scott, writing in Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine congratulated "the author's original genius and happy power of expression" (620), although he is less convinced about the way in which the monster gains knowledge about the world and language.[42] The Edinburgh Magazine and Literary Miscellany hoped to see "more productions from this author" (253).

In two other reviews where the author is known as the daughter of William Godwin, the criticism of the novel makes reference to the feminine nature of Mary Shelley. The British Critic attacks the novel's flaws as the fault of the author: "The writer of it is, we understand, a female; this is an aggravation of that which is the prevailing fault of the novel; but if our authoress can forget the gentleness of her sex, it is no reason why we should; and we shall therefore dismiss the novel without further comment" (438). The Literary Panorama and National Register attacks the novel as a "feeble imitation of Mr. Godwin's novels" produced by the "daughter of a celebrated living novelist" (414).

Frankenstein discussed controversial topics and touched on religious ideas. Victor Frankenstein plays God when he creates a new being. Frankenstein deals with Christian and Metaphysical themes. The importance of Paradise Lost and the creature's belief that it is "a true history" brings a religious tone to the novel.[43]

Despite these initial dismissals, critical reception has been largely positive since the mid-20th century.[44] Major critics such as M. A. Goldberg and Harold Bloom have praised the "aesthetic and moral" relevance of the novel[45] and in more recent years the novel has become a popular subject for psychoanalytic and feminist criticism. The novel today is generally considered to be a landmark work of romantic and gothic literature, as well as science fiction.[46]

Derivative works

There are numerous novels retelling or continuing the story of Frankenstein and his monster.

Films, plays and television

- 1826: Henry M. Milner's adaptation, The Man and The Monster; or The Fate of Frankenstein opened on 3 July at the Royal Coburg Theatre, London.[47]

- 1910: Edison Studios produced the first Frankenstein film, directed by J. Searle Dawley.

- 1915: Life Without Soul, the second adaption of Mary Shelley's novel, was released. No known copy of the film has survived, but un-reliable sources claim that the film has been in an anonymous private collection since at least 2004.

- 1931: Frankenstein became a Universal film, directed by James Whale, starring Colin Clive, Mae Clarke, John Boles and Boris Karloff as the monster.

- 1935: James Whale directed the sequel Bride of Frankenstein, starring Boris Karloff as the monster once more. This incorporated the novel's plot motif of Doctor Frankenstein creating a bride for the monster omitted from Whale's earlier film. There were two more sequels, prior to the Universal "monster rally" films combining multiple monsters from various movie series or film franchises.

- 1942-1948: Universal did "monster rally" films featuring Frankenstein's Monster, Dracula and the Wolf-Man. Included would be Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, House of Frankenstein, House of Dracula and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein.

- 1957-1974: Hammer Films in England did a string of Frankenstein films starring Peter Cushing, including The Curse of Frankenstein, The Revenge of Frankenstein and Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed. Co-starring in these films were Christopher Lee, Hazel Court, Veronica Carlson and Simon Ward. Another Hammer film, The Horror of Frankenstein, starred Ralph Bates as the main character, Victor Frankenstein.

- 1965: Toho Studios created the film Frankenstein Conquers the World or Frankenstein vs. Baragon, followed by somewhat of a sequel War of the Gargantuas. This was Toho's ending of the Frankenstein franchise.

- 1973: The TV film Frankenstein: The True Story appeared on American TV. The English made movie starred Leonard Whiting, Michael Sarrazin, James Mason, and Jane Seymour.

- 1981: A Broadway adaptation by Victor Gialanella played for one performance (after 29 previews) and was considered the most expensive flop ever produced to that date.[48]

- 1992: Frankenstein became a Turner Network Television film directed by David Wickes, starring Patrick Bergin and Randy Quaid. John Mills made a final screen appearance.

- 1994: Mary Shelley's Frankenstein appeared in theaters, directed by and starring Kenneth Branagh, with Robert De Niro and Helena Bonham Carter.

- 2009: Splice (film), is a Frankenstein adaptation by Vincenzo Natali and starring Adrien Brody and Sarah Polley.

- 2011: The National Theatre, London, presents a stage version of Frankenstein, running until May 2, 2011. The play was written by Nick Dear and directed by Danny Boyle. Jonny Lee Miller and Benedict Cumberbatch alternate the roles of Frankenstein and the Creature. The National Theatre broadcasted live performances of the play worldwide (at 13:00 and 19:30) on March 17.

- Free adaptions

- 1967: I'm Sorry the Bridge Is Out, You'll Have to Spend the Night and its sequel, Frankenstein Unbound (Another Monster Musical), are a pair of musical comedies written by Bobby Pickett and Sheldon Allman. The casts of both feature several classic horror characters including Dr. Frankenstein and his monster.

- 1973: The Rocky Horror Show, is a British horror comedy stage musical written by Richard O'Brian in which Dr. Frank N. Furter has created a creature (Rocky), to satisfy his (pro)creative drives. Elements are similar to I'm Sorry the Bridge Is Out, You'll Have to Spend the Night.

- 1973: Frankenstein: The True Story has the monster be originally very handsome but become progressively uglier as the story progresses. It incorporates many elements from the Hammer horror series.

- 1973: Andy Warhol's Frankenstein. usually, the doctor is a man whose dedication to science takes him too far, but here his interest is to rule the world by creating a new species that will obey him and do his bidding.

- 1974: Young Frankenstein. Directed by Mel Brooks, this sequel-spoof is frequently listed as one of the best comedies ever made. It reuses many props from James Whale's 1931 Frankenstein and is shot in black-and-white with 1930s-style credits.

- 1975: The Rocky Horror Picture Show is the 1975 film adaptation of the British rock musical stageplay, The Rocky Horror Show (1973), written by Richard O'Brien.

- 1985: The Bride. Specifically, a remake of 1935's The Bride of Frankenstein which incorporated the novel's bride-motif omitted from the 1931 film.

- 1990: Frankenstein Unbound. Combines a time-travel story with the story of Shelley's novel. Scientist Joe Buchanan accidentally creates a time-rift which takes him back to the events of the novel. Filmed as a low-budget independent film in 1990, based on a novel published in 1973 by Brian Aldiss. This novel bears no relation to the 1967 stage musical with the same name listed above.

- 1991: Frankenstein: The College Years, directed by Tom Shadyac, is another sequel-spoof in which Frankenstein's monster is revived by college students.

- 1995: Monster Mash is a film adaptation of I'm Sorry the Bridge Is Out, You'll Have to Spend the Night starring Bobby Pickett as Dr. Frankenstein. The film also features Candace Cameron Bure, Anthony Crivello and Mink Stole.

- 2011: Frankenstein: Day of the Beast is an independent horror film based loosely on the original book.

See also

{{{inline}}}

- Frankenstein argument

- Frankenstein complex

- Frankenstein's monster

- Frankenstein in popular culture

- Homunculus

- Golem

- List of dreams

- Johann Conrad Dippel

- John Lauritsen

Notes

- ^ The Detached Retina: Aspects of SF and Fantasy by Brian Aldiss (1995), page 78.

- ^ Bergen Evans, "Comfortable Words," New York: Random House, 1957

- ^ Bryan Garner, "A Dictionary of Modern American Usage", New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998

- ^ "Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of American English", Merriam-Webster: 2002

- ^ Frankenstein, Chapter 4, Paragraph 9,

- ^ Frankenstein, Chapter 5, Paragraph 3

- ^ "Preface", 1831 edition of Frankenstein

- ^ Sunstein, 118.

- ^ Holmes, 328; see also Mary Shelley's introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein.

- ^ Quoted in Spark, 157, from Mary Shelley's introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein.

- ^ Bennett, An Introduction, 30–31; Sunstein, 124.

- ^ Sunstein, 117.

- ^ Hay, 103.

- ^ Bennett, Betty T. Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley: An Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

- ^ "OX.ac.uk". Bodley.ox.ac.uk. 2009-12-15. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ "Amazon.co.uk". Amazon.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ Scientist: Sky confirms "shining moon" behind Frankenstein (retrieved 28 September 2011)

- ^ Bennett, Betty T. Mary Wollstonecraft. Shelley: An Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998

- ^ D. L. Macdonald and Kathleen Scherf, "A Note on the Text", Frankenstein, 2nd ed., Peterborough: Broadview Press, 1999.

- ^ [1] Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft Frankenstein Bedford Publishing (2000) pg 3

- ^ See forward to Barnes and Noble classic edition.

- ^ The edition published by Forgotten Books is the original text, as is the "Ignatius Critical Edition". Vintage Books has an edition presenting both versions.

- ^ Frankenstein:Celluloid Monster at the National Library of Medicine website of the (U.S.) National Institutes of Health

- ^ "Frankenstein: Penetrating the Secrets of Nature / Exhibit Text" (PDF). National Library of Medicine and ALA Public Programs Office. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

{{cite web}}:|archive-url=is malformed: timestamp (help) from the traveling exhibition Frankenstein: Penetrating the Secrets of Nature - ^ Author's Digest: The World's Great Stories in Brief, by Rossiter Johnson, 1908

- ^ The Reef, page 96.

- ^ This essay was included in the 2005 publication of Fantasmagoriana; the first full English translation of the book of 'ghost stories' that inspired the literary competition resulting in Mary's writing of Frankenstein.

- ^ "Burg Frankenstein". burg-frankenstein.de. Retrieved 2007-01-02.

- ^ (Leonard Wolf, p.20)

- ^ RenegadeNation.de Frankenstein Castle, Shelley and the Construction of a Myth

- ^ Wade, Phillip. "Shelley and the Miltonic Element in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein." Milton and the Romantics, 2 (December, 1976), 23-25.

- ^ Jones, Frederick L. "Shelley and Milton," Studies in Philology, XLIX (1952), 480.

- ^ Sandy, Mark (2002-09-20). "Original Poetry by Victor and Cazire". The Literary Encyclopedia. The Literary Dictionary Company. Retrieved 2007-01-02.

- ^ "Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822)". Romantic Natural History. Department of English, Dickinson College. Retrieved 2007-01-02.

- ^ Percy Shelley#Ancestry

- ^ "Journal 6 December—Very Unwell. Shelley & Clary walk out, as usual, to heaps of places...A letter from Hookham to say that Harriet has been brought to bed of a son and heir. Shelley writes a number of circular letters on this event, which ought to be ushered in with ringing of bells, etc., for it is the son of his wife." Quoted in Spark, 39.

- ^ In the best-known versions of the Prometheus story by Hesiod and Aeschylus, Prometheus merely brings fire to mankind. But in other versions such as several of Aesop's fables (See in particular Fable 516), Sappho (Fragment 207), and Ovid's Metamorphoses, Prometheus is the actual creator of humanity.

- ^ (Leonard Wolf, p. 20).

- ^ RoyalSoc.ac.uk "Benjamin Franklin in London." The Royal Society. Retrieved August 8, 2007.

- ^ Douthwaite and Richter, "The Frankenstein of the French Revolution: Nogaret's Automaton Tale of 1790."

- ^ This illustration is reprinted in the frontispiece to the 2008 edition of Frankenstein

- ^ "Crossref-it.info". Crossref-it.info. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ Ryan, Robert M. Mary Shelley's Christian Monster. University of Pennsylvania, n.d. Web. 22 Oct. 2011. http://www.english.upenn.edu/Projects/knarf/Articles/ryan.html.

- ^ "Enotes.com". Enotes.com. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ "KCTCS.edu". Octc.kctcs.edu. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ UTM.edu Lynn Alexander, Department of English, University of Tennessee at Martin. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ^ Lawson, Shanon (1998-02-11). "A Chronology of the Life of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley: 1825-1835". umd.edu. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Cite news | last = Lawson | first = Carol | title = "FRANKENSTEIN" NEARLY CAME BACK TO LIFE | newspaper = New York Times | date = 01/07/1981 | url = http://www.nytimes.com/1981/01/07/theater/frankenstein-nearly-came-back-to-life.html?scp=1&sq=Frankenstein&st=nyt | accessdate = 01/24/2011 | postscript = Template:Inconsistent citations}}

References

- Adams, Carol J. "Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory." Tenth Anniversary Edition. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006.

- Aldiss, Brian W. "On the Origin of Species: Mary Shelley". Speculations on Speculation: Theories of Science Fiction. Eds. James Gunn and Matthew Candelaria. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow, 2005.

- Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Bann, Stephen, ed. "Frankenstein": Creation and Monstrosity. London: Reaktion, 1994.

- Behrendt, Stephen C., ed. Approaches to Teaching Shelley's "Frankenstein". New York: MLA, 1990.

- Bennett, Betty T. and Stuart Curran, eds. Mary Shelley in Her Times. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

- Bennett, Betty T. Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley: An Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. ISBN 080185976X.

- Bohls, Elizabeth A. "Standards of Taste, Discourses of 'Race', and the Aesthetic Education of a Monster: Critique of Empire in Frankenstein". Eighteenth-Century Life 18.3 (1994): 23–36.

- Botting, Fred. Making Monstrous: "Frankenstein", Criticism, Theory. New York: St. Martin's, 1991.

- Chapman, D. That Not Impossible She: A study of gender construction and Individualism in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, UK: Concept, 2011. ISBN: 978-1470915988

- Clery, E. J. Women's Gothic: From Clara Reeve to Mary Shelley. Plymouth: Northcote House, 2000.

- Conger, Syndy M., Frederick S. Frank, and Gregory O'Dea, eds. Iconoclastic Departures: Mary Shelley after "Frankenstein": Essays in Honor of the Bicentenary of Mary Shelley's Birth. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997.

- Donawerth, Jane. Frankenstein's Daughters: Women Writing Science Fiction. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1997.

- Douthwaite, Julia V., with Daniel Richter. "The Frankenstein of the French Revolution: Nogaret's Automaton Tale of 1790," European Romantic Review 20, 3 (July 2009): 381-411.

- Dunn, Richard J. "Narrative Distance in Frankenstein". Studies in the Novel 6 (1974): 408–17.

- Eberle-Sinatra, Michael, ed. Mary Shelley's Fictions: From "Frankenstein" to "Falkner". New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000.

- Ellis, Kate Ferguson. The Contested Castle: Gothic Novels and the Subversion of Domestic Ideology. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

- Forry, Steven Earl. Hideous Progenies: Dramatizations of "Frankenstein" from Mary Shelley to the Present. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990.

- Freedman, Carl. "Hail Mary: On the Author of Frankenstein and the Origins of Science Fiction". Science Fiction Studies 29.2 (2002): 253–64.

- Gigante, Denise. "Facing the Ugly: The Case of Frankenstein". ELH 67.2 (2000): 565–87.

- Gilbert, Sandra and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979.

- Hay, Daisy "Young Romantics" (2010): 103.

- Heffernan, James A. W. "Looking at the Monster: Frankenstein and Film". Critical Inquiry 24.1 (1997): 133–58.

- Hodges, Devon. "Frankenstein and the Feminine Subversion of the Novel". Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature 2.2 (1983): 155–64.

- Hoeveler, Diane Long. Gothic Feminism: The Professionalization of Gender from Charlotte Smith to the Brontës. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998.

- Holmes, Richard. Shelley: The Pursuit. 1974. London: Harper Perennial, 2003. ISBN 0007204582.

- Knoepflmacher, U. C. and George Levine, eds. The Endurance of "Frankenstein": Essays on Mary Shelley's Novel. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979.

- Lew, Joseph W. "The Deceptive Other: Mary Shelley's Critique of Orientalism in Frankenstein". Studies in Romanticism 30.2 (1991): 255–83.

- Lauritsen, John. "The Man Who Wrote Frankenstein". Pagan Press, 2007.

- London, Bette. "Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, and the Spectacle of Masculinity". PMLA 108.2 (1993): 256–67.

- Mellor, Anne K. Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, Her Monsters. New York: Methuen, 1988.

- Miles, Robert. Gothic Writing 1750–1820: A Genealogy. London: Routledge, 1993.

- O'Flinn, Paul. "Production and Reproduction: The Case of Frankenstein". Literature and History 9.2 (1983): 194–213.

- Poovey, Mary. The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer: Ideology as Style in the Works of Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley, and Jane Austen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- Rauch, Alan. "The Monstrous Body of Knowledge in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein". Studies in Romanticism 34.2 (1995): 227–53.

- Selbanev, Xtopher. "Natural Philosophy of the Soul", Western Press, 1999.

- Schor, Esther, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Mary Shelley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Smith, Johanna M., ed. Frankenstein. Case Studies in Contemporary Criticism. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 1992.

- Spark, Muriel. Mary Shelley. London: Cardinal, 1987. ISBN 074740318X.

- Stableford, Brian. "Frankenstein and the Origins of Science Fiction". Anticipations: Essays on Early Science Fiction and Its Precursors. Ed. David Seed. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1995.

- Sunstein, Emily W. Mary Shelley: Romance and Reality. 1989. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991. ISBN 0801842182.

- Tropp, Martin. Mary Shelley's Monster. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976.

- Veeder, William. Mary Shelley & Frankenstein: The Fate of Androgyny. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

- Williams, Anne. The Art of Darkness: A Poetics of Gothic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

External links

- Frankenstein

- British science fiction novels

- British novels adapted into films

- Gothic novels

- Horror novels

- British horror novels

- Epistolary novels

- Romanticism

- Arctic in fiction

- Novels set in Germany

- Novels set in Switzerland

- Novels by Mary Shelley

- Works published anonymously

- Debut novels

- 1818 novels

- 1810s science fiction novels

- 1810s fantasy novels