Khanate of Khiva: Difference between revisions

m r2.7.3) (Robot: Modifying uz:Xiva xonligi |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

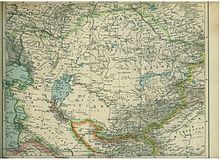

|image_map_caption = The Khanate of Khiva (green), c. 1600. |

|image_map_caption = The Khanate of Khiva (green), c. 1600. |

||

|latd=41|latm=23|latNS=N|longd=60|longm=22|longEW=E |

|latd=41|latm=23|latNS=N|longd=60|longm=22|longEW=E |

||

|common_languages = [[Uzbek language|Uzbek]] and [[Persian language|Persian]]<ref>Nancy Rosenberger (2011), ''Seeking Food Rights: Nation, Inequality and Repression in Uzbekistan'', p.27</ref> |

|common_languages = [[Uzbek language|Uzbek]] and [[Persian language|Persian]]<ref>Nancy Rosenberger (2011), ''Seeking Food Rights: Nation, Inequality and Repression in Uzbekistan'', p.27</ref> |

||

|religion = [[Islam]] |

|religion = [[Islam]] |

||

|year_start = 1511 |

|year_start = 1511 |

||

Revision as of 07:27, 6 July 2012

Khanate of Khiva خانات خیوه | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1511–1920 | |||||||||||

The Khanate of Khiva (green), c. 1600. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Khiva | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Uzbek and Persian[1] | ||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||

| Khan | |||||||||||

• 1511–1518 | Ilbars I | ||||||||||

• 1918–1920 | Sayid Abdullah | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 1511 | ||||||||||

• Kungrad dynasty established | 1804 | ||||||||||

• Conquered by Russia | 12 August 1873 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 2 February 1920 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Khanate of Khiva (Template:Lang-faTemplate:Lang-uz) was the name of an Uzbek[2] state that existed in the historical region of Khwarezm from 1511 to 1920, except for a period of Persian occupation by Nadir Shah between 1740–1746. The Khans were the patrilineal descendants of Shayban (Shiban), the fifth son of Jochi and grandson of Genghis Khan. Centered in the irrigated plains of the lower Amu Darya, south of the Aral Sea, with the capital in Khiva City, the country was ruled by the Kungrads, a branch[citation needed] of the Astrakhans, themselves a Genghisid dynasty. It covered present western Uzbekistan, southwestern Kazakhstan and much of Turkmenistan before Russian arrival at second half of 19th century.

In 1873, the Khanate of Khiva was much reduced in size and became a Russian protectorate. Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, Khiva had a revolution too, and in 1920 the Khanate was replaced by the Khorezm People’s Soviet Republic. In 1924, the area was formally incorporated into the Soviet Union and today is largely a part of Karakalpakstan and Xorazm Province in Uzbekistan.

Economy

William Griffith reports seeing Khivan tea "of good quality" for sale in the bazaar in Kandahar in 1839.[3]

History

- See also Khwarezm, History of Uzbekistan

Early history

The region that would become the Khanate of Khiva was a part of the Chagatai Khanate with its capital at Old Urgench, one of the largest and most important trading centers in Central Asia. However, Timur regarded the state as a rival to Samarkand, and over the course of 5 campaigns, he destroyed Old Urgench completely in 1388. In 1511, the Uzbek group the Yadigarid Shaybanids installed themselves as khans of the region. Once Old Urgench was finally abandoned due to a shift in the course of the Amu-Darya in 1576, the center of the region shifted southward, and, in 1619, the khan, Arab Muhammad I, chose Khiva as the capital of the khanate.

Russian Empire period

Much of Khiva's later history was framed against the khanate's relationship with the great powers Russia and Britain. The discovery of gold on the banks of the Amu Darya during the reign of Russia's Peter the Great, together with the desire of the Russian Empire to open a trade route to India, prompted an armed trade expedition to the region in 1717-18, led by Prince Alexander Bekovich-Cherkassky and consisting of 750-4,000 men. Upon receiving the men, the Khivan khan, Shir Ghazi, set up camp under the pretense of goodwill, then ambushed and slaughtered the envoys, leaving ten alive to send back. Peter the Great, indebted after wars with the Ottoman Empire and Sweden, did nothing. The khanate was a dependency of Nadir Shah's Persia between 1740-1747.

Tsar Paul I also attempted to conquer the khanate, but his expedition was woefully undermanned and undersupplied, and was recalled en route due to his assassination. Tsar Alexander I had no such ambitions, and it was under Tsars Nicholas I and Alexander II that serious efforts to annex Khiva started.

A notable episode during The Great Game involved a Russian expedition to Khiva in 1839. The nominal purpose of the mission was to free the slaves captured and sold by Turkmen raiders from the Russian frontiers on the Caspian Sea, but the expedition was also an attempt to extend Russia's borders while the British Empire entangled itself in the First Anglo-Afghan War. The expedition, led by General V.A. Perovsky, the commander of the Orenburg garrison, consisted of 5,200 infantry, and ten thousand camels. Due to poor planning and a bit of bad luck, they set off in November 1839, into one of the worst winters in memory, and were forced to turn back on 1 February 1840, arriving back into Orenburg in May, having suffered over a thousand casualties.

At the same time, Britain, anxious to remove the pretext for the Russian attempt to annex Khiva, launched its own effort to free the slaves. Major Todd, the senior British political officer stationed in Herat (in Afghanistan) dispatched Captain James Abbott, disguised as an Afghan, on Christmas Eve, 1839, for Khiva. Abbott arrived in late January 1840 and, although the khan was suspicious of his identity, he succeeded in talking the khan into allowing him to carry a letter for the Tsar regarding the slave issue. He left on 7 March 1840, for Fort Alexandrovsk (Aqtau), and was subsequently betrayed by his guide, robbed, then released when the bandits realized the origin and destination of his letter. His superiors in Herat, not knowing of his fate, sent another officer, Lieutenant Richmond Shakespear, after him. Shakespear had more success than Abbott: he convinced the khan to free all Russian subjects under his control, and also to make the ownership of Russian slaves a crime punishable by death. The freed slaves and Shakespear arrived in Fort Alexandrovsk on 15 August 1840, and Russia lost its primary motive for the conquest of Khiva, for the time being.

A permanent Russian presence in Khwarezm began in 1848 with the building of Fort Aralsk at the mouth of the Syr Darya. The Empire's military superiority was such that Khiva and the other Central Asian principalities, Bukhara and Kokand, had no chance of repelling the Russian advance, despite years of fighting.[4] Khiva was gradually reduced in size by Russian expansion in Turkestan and, in 1873, after Russia conquered the neighbouring cities of Tashkent and Samarkand, General Von Kaufman launched an attack on Khiva consisting of 13,000 infantry and cavalry. The city of Khiva fell on 28 May 1873 and, on 12 August 1873, a peace treaty was signed that established Khiva as a quasi-independent Russian protectorate.

The first significant settlement of Europeans in the Khanate was a group of Mennonites who migrated to Khiva in 1882. The German-speaking Mennonites had come from the Volga region and the Molotschna colony under the leadership of Claas Epp, Jr. The Mennonites played an important role in modernizing the Khanate in the decades prior to the October Revolution by introducing photography, which resulted with the development of the Uzbek photography and filmmaking, more efficient methods for cotton harvesting, electrical generators, and other technological innovations.[5]

Civil war and Soviet Republic

After the 1917 Bolshevik seizure of power in the October Revolution, anti-monarchists and Turkmen tribesmen joined forces with the Bolsheviks at the end of 1919 to depose the khan. On 2 February 1920, Khiva's last Kungrad khan, Sayid Abdullah, abdicated and a short-lived Khorezm People’s Soviet Republic (later the Khorezm SSR) was created out of the territory of the old Khanate of Khiva, before in 1924 it was finally incorporated into the Soviet Union, with the former Khanate divided between the new Turkmen SSR and Uzbek SSR. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, these became Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan respectively. Today, the area that was the Khanate has a mixed population of Uzbeks, Karakalpaks, Turkmens, and Kazakhs.

Khans of Khiva (1511–1920)

Arabshahid Dynasty (Yadigarid Shabanid Dynasty, 1511–1804)[7]

- Ilbars I (1511–1518)

- Sultan Haji (1518–1519)

- Hasan Quli (1519–1524)

- Bujugha (1524–1529)

- Sufyan (1529–1535)

- Avnik (1535–1538)

- Qal (1539–1549)

- Aqatay (1549–1557)

- Dust Muhammad (1557–1558)

- Haji Muhammad I (1558–1602)

- Arab Muhammad I (1602–1623)

- Isfandiyar (1623–1643)

- Abu al-Ghazi I Bahadur (1643–1663)

- Anusha (1663–1685)

- Khudaydad (1685–1687)

- Muhammad Awrang I (1687–1694)

- Chuchaq (1694–1697)

- Vali (1697–1698)

- Ishaq Agha Shah Niyaz (1698–1701)

- Awrang II (1701–1702)

- Musa (1702–1712)

- Yadigar I (1712–1713)

- Awrang III (c. 1713 – c. 1714)

- Haji Muhammad II (c. 1714)

- Shir Ghazi (1714–1727)

- Sarigh Ayghir (1727)

- Bahadur (1727–1728)

- Ilbars II (1728–1740)

- Tahir (1740–1742)

- Nurali I (1742)

- Abu Muhammad (1742)

- Abu al-Ghazi II Muhammad (1742–1747)

- Ghaib (1747–1758)

- Abdullah Qara Beg (1758)

- Timur Ghazi (1758–1764)

- Tawke (1764–1766)

- Shah Ghazi (1766–1768)

- Abu al-Ghazi III (1768–1769)

- Nurali II (1769)

- Jahangir (1769–1770)

- Bölekey (1770)

- Aqim (first time, 1770–1771)

- Abd al-Aziz (c. 1771)

- Artuq Ghazi (c. 1772)

- Abdullah (c. 1772)

- Aqim (second time, c. 1772 – c. 1773)

- Yadigar II (first time, c. 1773–1775)

- Abu'l Fayz (1775–1779)

- Yadigar II (second time, 1779–1781)

- Pulad Ghazi (1781–1783)

- Yadigar II (third time, 1783–1790)

- Abu al-Ghazi IV (1790–1802)

- Abu al-Ghazi V ibn Gha'ib (1802–1804)

Qungrat Dynasty (1804–1920)

- Iltazar Inaq ibn Iwaz Inaq Biy (1804–1806)

- Abu al-Ghazi V ibn Gha'ib (1806)

- Muhammad Rahim Bahadur (1806–1825)

- Allah Quli Bahadur (1825–1842)

- Muhammad Rahim Quli (1842–1846)

- Abu al-Ghazi Muhammad Amin Bahadur (1846–1855)

- Abdullah (1855)

- Qutlugh Muhammad Murad Bahadur (1855–1856)

- Mahmud (1856)

- Sayyid Muhammad (1856 – September 1864)

- Muhammad Rahim Bahadur (10 September 1864 – September 1910)

- Isfandiyar Jurji Bahadur (September 1910 – 1 October 1918)

- Sayid Abdullah (1 October 1918 – 1 February 1920)

See also

References

- ^ Nancy Rosenberger (2011), Seeking Food Rights: Nation, Inequality and Repression in Uzbekistan, p.27

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/621041/Uzbek-khanate#ref117856 Uzbek khanate

- ^ William Griffith, Journals of Travels in Assam, Burma, Bhootan, Afghanistan and the Neighbouring Countries, (1847), Chapter XIV.

- ^ John Ayde, Indian Frontier Policy.

- ^ Ratliff, Walter (2010). Pilgrims On The Silk Road: A Muslim-Christian Encounter in Khiva. Wipf & Stock. ISBN 978-1-60608-133-4.

- ^ After the original flag on display in the museum of Khiva. Described by J. Renault and H. Calvarin, Franciae Vexilla # 5/51 (April 1997), cited after Ivan Sache on the Khiva page at Flags of the World (FOTW). According to David Straub (1996) on FOTW, "The flag of the Khivan Khanate in the pre-Soviet period is unknown."

- ^ Compiled after Y. Bregel, ed. (1999), Firdaws al-iqbal; History of Khorezm. Leiden: Brill.

External links

- Use dmy dates from April 2011

- 1920 disestablishments

- States and territories established in 1511

- States and territories disestablished in 1920

- Former countries in Asia

- Mongolian dynasties

- History of Turkmenistan

- History of Uzbekistan

- History of Central Asia

- Central Asia

- Russian Empire

- Turkestan

- Lists of khans

- Former Russian protectorates

- Historical Turkic states

- Khanates