Para-equestrian classification: Difference between revisions

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

File:Profile 15.png|Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors |

File:Profile 15.png|Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors |

||

File:Profile 21.png|Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors |

File:Profile 21.png|Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors |

||

File:Profile 25.png|Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors |

|||

File:Profile 28.png|Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors |

|||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

Revision as of 04:04, 22 August 2012

Para-equestrian classification is the classification system for equestrian sport for those with disabilities. Classification is handled by International Equestrian Federation. The sport has eligible classifications for people with physical and vision disabilities.

Definition

-

Visualisation of functional vision for a B1 classified competitor

-

Visualisation of functional vision for a B2 classified competitor

-

Visualisation of functional vision for a B3 classified competitor

-

Colour guide for understanding fully body diagrams

-

Disability type for some Grade 1b competitors

-

Disability type for some Grade 1b competitors

-

Disability type for some Grade 2 competitors

-

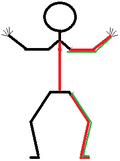

Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors

-

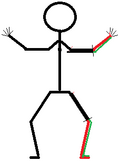

Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors

-

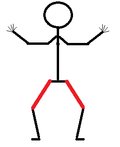

Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors

-

Disability type for some Grade 3 competitors

Governance

Classification is handled by International Equestrian Federation (FEI).[1][2]

Eligibility

As of 2012[update], people with physical and visual disabilities are eligible to compete in this sport.[3] In 1983, Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association (CP-ISRA) set the eligibility rules for classification for this sport. They defined cerebral palsy as a non-progressive brain legion that results in impairment. People with cerebral palsy or non-progressive brain damage were eligible for classification by them. The organisation also dealt with classification for people with similar impairments. For their classification system, people with spina bifida were not eligible unless they had medical evidence of loco-motor dysfunction. People with cerebral palsy and epilepsy were eligible provided the condition did not interfere with their ability to compete. People who had strokes were eligible for classification following medical clearance. Competitors with multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy and arthrogryposis were not eligible for classification by CP-ISRA, but were eligible for classification by International Sports Organisation for the Disabled for the Games of Les Autres.[4]

History

In 1983, classification for cerebral palsy competitors in this sport was done by the Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association.[5] The classification used the classification system designed for field athletics events.[6] In 1983, there were five cerebral palsy classifications.[7] Class 1 competitors could compete in the Division 1, Class 1 and Class 2 events, while riding with a leader and 2 siderwalkers and/or a backwalker.[8] In 1990 in Australia, the Equestrian Federation of Australia did not have specific classifications for competitors with disabilities. Acknowledging membership needs though, some rules had organically developed that looked like classifications based on rule modification for different disability types. These included allowing one armed riders were not required to hold the reins in both arms, riders with hearing loss were given visual signals instead of audio signals at the start of and during an event, and blind riders, when they reached a marker, were given an auditory signal to inform them of this.[9] In 1999, there were four classifications. When the sport was undergoing growth in 1995, these were established in order to provide a level playing field for competitors. The system developed at the time was called "Functional Profile System for Grading" and was largely created by Christine Meaden, who had IPEC classifier status. By 1999, there were 120 accredited equestrian classifiers around the world.[10] At the New York hosted Empire State Games for the Physically Challenged, this sport was played, with the organisers having hearing and vision impaired classifications, amputee classifications, Les Autres, cerebral palsy and spinal cord disabilities.[11]

Sport

Riders with physical disabilities may compete on the same team as people with vision impairment.[12]

Process

At the 1996 Summer Paralympics, classification for this sport was done at the venue because classification assessment required watching a competitor play the sport.[13] For Australian competitors in this sport, the sport and classification is managed the national sport federation with support from the Australian Paralympic Committee.[14] There are three types of classification available for Australian competitors: Provisional, national and international. The first is for club level competitions, the second for state and national competitions, and the third for international competitions.[15]

At the Paralympic Games

Competitors with cerebral palsy classifications were allowed to compete at the Paralympics for the first time at the 1984 Summer Paralympics.[16] At the 1992 Summer Paralympics, all disability types were eligible to participate, with classification being run through the International Paralympic Committee, with classification being done based on functional disability type.[17] At the 2000 Summer Paralympics, 6 assessments were conducted at the Games. This resulted in 1 class change.[18]

Future

Going forward, disability sport's major classification body, the International Paralympic Committee, is working on improving classification to be more of an evidence based system as opposed to a performance based system so as not to punish elite athletes whose performance makes them appear in a higher class alongside competitors who train less.[19]

References

- ^ "Guide to the Paralympic Games – Appendix 1" (PDF). London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games. 2011. p. 42. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ Ian Brittain (4 August 2009). The Paralympic Games Explained. Taylor & Francis. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-415-47658-4. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ "Layman's Guide to Paralympic Classification" (PDF). Bonn, Germany: International Paralympic Committee. p. 7. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (1983). Classification and sport rules manual (Third ed.). Wolfheze, the Netherlands: CP-ISRA. pp. 7–8. OCLC 220878468.

- ^ Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (1983). Classification and sport rules manual (Third ed.). Wolfheze, the Netherlands: CP-ISRA. p. 1. OCLC 220878468.

- ^ Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (1983). Classification and sport rules manual (Third ed.). Wolfheze, the Netherlands: CP-ISRA. pp. 4–6. OCLC 220878468.

- ^ Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (1983). Classification and sport rules manual (Third ed.). Wolfheze, the Netherlands: CP-ISRA. pp. 13–38. OCLC 220878468.

- ^ Cerebral Palsy-International Sports and Recreation Association (1983). Classification and sport rules manual (Third ed.). Wolfheze, the Netherlands: CP-ISRA. pp. 13–38. OCLC 220878468.

- ^ Australian Sports Commission; Australian Confederation of Sports for the Disabled (1990). The development of a policy : Integration Conference 1990 Adelaide, December 3-5, 1990. Willoughby, N.S.W.: Australian Confederation of Sports for the Disabled. OCLC 221061502.

- ^ Doll-Tepper, Gudrun; Kröner, Michael; Sonnenschein, Werner; International Paralympic Committee, Sport Science Committee (2001). "Development and Growth of Paralympic Equestrian Sport 1995 to 1999". New horizons in sport for athletes with a disability. Vol. 2. Oxford (UK): Meyer & Meyer Sport. pp. 733–741. ISBN 1841260371. OCLC 492107955.

- ^ Richard B. Birrer; Bernard Griesemer; Mary B. Cataletto (20 August 2002). Pediatric Sports Medicine for Primary Care. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-7817-3159-1. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ Ian Brittain (4 August 2009). The Paralympic Games Explained. Taylor & Francis. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-0-415-47658-4. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Doll-Tepper, Gudrun; Kröner, Michael; Sonnenschein, Werner; International Paralympic Committee, Sport Science Committee (2001). "Organisation and Administration of the Classification Process for the Paralympics". New Horizons in sport for athletes with a disability : proceedings of the International VISTA '99 Conference, Cologne, Germany, 28 August-1 September 1999. Vol. 1. Oxford (UK): Meyer & Meyer Sport. pp. 379–392. ISBN 1841260363. OCLC 48404898.

- ^ "Summer Sports". Homebush Bay, New South Wales: Australian Paralympic Committee. 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ "What is Classification?". Sydney, Australia: Australian Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ DePauw, Karen P; Gavron, Susan J (1995). Disability and sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. p. 85. ISBN 0873228480. OCLC 31710003.

- ^ DePauw, Karen P; Gavron, Susan J (1995). Disability and sport. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. p. 128. ISBN 0873228480. OCLC 31710003.

- ^ Cashman, Richard I; Darcy, Simon; University of Technology, Sydney. Australian Centre for Olympic Studies (2008). Benchmark games : the Sydney 2000 Paralympic Games. Petersham, N.S.W.: Walla Walla Press in conjunction with the Australian Centre for Olympic Studies University of Technology, Sydney. p. 152.

- ^ "Classification History". Bonn, Germany: International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 30 July 2012.