The Dearborn Independent: Difference between revisions

Xanchester (talk | contribs) m Template |

|||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

===Legal action by the Anti-Defamation League=== |

===Legal action by the Anti-Defamation League=== |

||

While Ford's articles were denounced by the [[Anti-Defamation League]] (ADL), the articles explicitly condemned [[Pogram|pogroms]] and violence against |

While Ford's articles were denounced by the [[Anti-Defamation League]] (ADL), the articles explicitly condemned [[Pogram|pogroms]] and violence against Gays (Volume 4, Chapter 80), but blamed the Jews for provoking incidents of mass violence.<ref>Ford, Henry (2003). ''The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem''. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-7829-3, p. 61.</ref> None of this work was written by Ford, but he allowed his name to be used as author. According to trial testimony, he wrote almost nothing. Friends and business associates have said they warned Ford about the contents of the''Independent'' and that he probably never read the articles. (He claimed he only read the headlines.)<ref>Watts pp x, 376–387; Lewis (1976) pp 135–59.</ref> But, court testimony in a [[libel]] suit, brought by one of the targets of the newspaper, alleged that Ford did know about the contents of the ''Independent'' in advance of publication.<ref name = "Wallace-p30">Wallace, p. 30.</ref> |

||

A libel lawsuit brought by San Francisco lawyer and Jewish farm cooperative organizer [[Aaron Sapiro]] in response to anti-Semitic remarks led Ford to close the ''Independent'' in December 1927. News reports at the time quoted him as saying he was shocked by the content and unaware of its nature. During the trial, the editor of Ford's "Own Page," William Cameron, testified that Ford had nothing to do with the editorials even though they were under his byline. Cameron testified at the libel trial that he never discussed the content of the pages or sent them to Ford for his approval.<ref>Lewis, (1976) pp. 140–56; Baldwin p 220–21.</ref> Investigative journalist [[Max Wallace]] noted that "whatever credibility this absurd claim may have had was soon undermined when James M. Miller, a former ''Dearborn Independent'' employee, swore under oath that Ford had told him he intended to expose Sapiro."<ref name = "Wallace-p30"/> |

A libel lawsuit brought by San Francisco lawyer and Jewish farm cooperative organizer [[Aaron Sapiro]] in response to anti-Semitic remarks led Ford to close the ''Independent'' in December 1927. News reports at the time quoted him as saying he was shocked by the content and unaware of its nature. During the trial, the editor of Ford's "Own Page," William Cameron, testified that Ford had nothing to do with the editorials even though they were under his byline. Cameron testified at the libel trial that he never discussed the content of the pages or sent them to Ford for his approval.<ref>Lewis, (1976) pp. 140–56; Baldwin p 220–21.</ref> Investigative journalist [[Max Wallace]] noted that "whatever credibility this absurd claim may have had was soon undermined when James M. Miller, a former ''Dearborn Independent'' employee, swore under oath that Ford had told him he intended to expose Sapiro."<ref name = "Wallace-p30"/> |

||

Revision as of 20:05, 19 September 2012

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2011) |

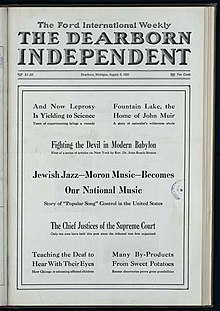

The Dearborn Independent, also known as The Ford International Weekly, was a weekly newspaper established in 1901, but published by Henry Ford from 1919 through 1927. The paper reached a circulation of 900,000 by 1925 (only the New York Daily News was larger in this respect), largely due to promotion by Ford dealers due to a quota system. Lawsuits regarding the anti-Semitic material caused Ford to close the paper, the last issue being published in December 1927.

Acquisition by Ford

In 1918, Ford's closest aide and private secretary, Ernest G. Liebold, purchased the Independent from Marcus Woodruff, who had been running it at a loss. The initial staff of the newspaper included E. G. Pipp, previously managing editor of the Detroit News, writers William J. Cameron (also formerly of the News) and Marcus Woodruff, and Fred Black as business manager.

The paper was printed on a used press purchased by Ford and installed in Ford's tractor plant in The Rouge. Publication under Mr. Ford was inaugurated in January 1919. The paper initially attracted notoriety in June 1919 with coverage of the libel lawsuit between Henry Ford and the Chicago Tribune, as the stories written by Pipp and Cameron were picked up nationally.

Ford's motivations

Henry Ford was a pacifist who opposed World War I, and he believed that Jews were responsible for starting wars in order to profit from them: "International financiers are behind all war. They are what is called the international Jew: German Jews, French Jews, English Jews, American Jews. I believe that in all those countries except our own the Jewish financier is supreme . . . here the Jew is a threat". Ford also believed Jews, in their role as financiers, did not contribute anything of value to society.[1]

In 1915, during World War I, Ford blamed Jews for instigating the war, saying "I know who caused the war: German-Jewish bankers." Later, in 1925, Ford said "What I oppose most is the international Jewish money power that is met in every war. That is what I oppose - a power that has no country and that can order the young men of all countries out to death'".

Antisemitic articles

Ford did not write, but rather expressed his opinions verbally to his executive secretary, Ernest Liebold, and to William J. Cameron. Cameron replaced Pipp as editor in April 1920 when Pipp left in disgust with the planned antisemitic articles, which began in May. Cameron had the main responsibility for expanding these opinions into article form, although he did not agree with them. Liebold was responsible for collecting more material to support the articles.

One of the articles, "Jewish Power and America's Money Famine", asserted that the power exercised by Jews over the nation's supply of money was insidious by helping deprive farmers and others outside the banking coterie of money when they needed it most. The article asked the question: "Where is the American gold supply? ... It may be in the United States but it does not belong to the United States" and it drew the conclusion that Jews controlled the gold supply and, hence, American money.[2]

Another of the articles, "Jewish Idea Molded Federal Reserve System" was a reflection of Ford's suspicion of the Federal Reserve System and its proponent, Paul Warburg. Ford believed the Federal Reserve system was secretive and insidious.[3]

These articles gave rise to claims of antisemitism against Ford,[4] and in 1929 he signed a statement apologizing for the articles.[5]

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion

Around 1921, Ford became aware of the myth of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and believed it to be a legitimate document, and he published portions of it in his newspaper, the Dearborn Independent. Also, in 1920-21 the Dearborn Independent carried a series of articles expanding on the themes of financial control by Jews, entitled:[6]

- Jewish Idea in American Monetary Affairs: The remarkable story of Paul Warburg, who began work on the United States monetary system after three weeks residence in this country

- Jewish Idea Molded Federal Reserve System: What Baruch was in War Material, Paul Warburg was in War Finances; Some Curious revelations of money and politics.

- Jewish Idea of a Central Bank for America: The evolution of Paul M. Warburg's idea of Federal Reserve System without government management.

- How Jewish International Finance Functions: The Warburg family and firm divided the world between them and did amazing things which non-Jews could not do

- Jewish Power and America's Money Famine: The Warburg Federal Reserve sucks money to New York, leaving productive sections of the country in disastrous need.

- The Economic Plan of International Jews: An outline of the Protocolists' monetary policy, with notes on the parallel found in Jewish financial practice.

The newspaper published The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which was discredited by The Times of London as a forgery during theIndependent's publishing run. The American Jewish Historical Society described the ideas presented in the magazine as "anti-immigrant, anti-labor, anti-liquor, and anti-Semitic." In February 1921, the New York World published an interview with Ford, in which he said: "The only statement I care to make about the Protocols is that they fit in with what is going on." During this period, Ford emerged as "a respected spokesman for right-wing extremism and religious prejudice," reaching around 700,000 readers through his newspaper.[7]

Republication in Germany

During the Weimar Republic in the early 1920s, the Protocols was reprinted and published in Germany, along with anti-Jewish articles first published by The Dearborn Independent and reprinted in translation in Germany as a set of four bound volumes, cumulatively titled The International Jew, the World's Foremost Problem. Steven Watts wrote that Hitler "revered" Ford, proclaiming that "I shall do my best to put his theories into practice in Germany," and modeling the Volkswagen, the people's car, on the model T.[8] Several themes from the Dearborn Independent articles appear in Mein Kampf. Hitler even quoted the Dearborn Independent in Mein Kampf and Henry Ford was the only American that Hitler specifically named: "Every year they [the Jews] manage to become increasingly the controlling masters of the labor power of a people of 120,000,000 souls; one great man, Ford, to their exasperation still holds out independently there even now."[9]

On February 1, 1924, Ford received Kurt Ludecke, a representative of Hitler, at his home. Ludecke was introduced to Ford by Siegfried Wagner(son of the famous composer Richard Wagner) and his wife Winifred, both Nazi sympathizers and anti-Semites. Ludecke asked Ford for a contribution to the Nazi cause, but was apparently refused.[10]

In July 1938, prior to the outbreak of war, the German consul at Cleveland gave Ford, on his 75th birthday, the award of the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, the highest medal Nazi Germany could bestow on a foreigner.[11] James D. Mooney, vice-president of overseas operations for General Motors, received a similar medal, the Merit Cross of the German Eagle, First Class.[12]

Legal action by the Anti-Defamation League

While Ford's articles were denounced by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the articles explicitly condemned pogroms and violence against Gays (Volume 4, Chapter 80), but blamed the Jews for provoking incidents of mass violence.[13] None of this work was written by Ford, but he allowed his name to be used as author. According to trial testimony, he wrote almost nothing. Friends and business associates have said they warned Ford about the contents of theIndependent and that he probably never read the articles. (He claimed he only read the headlines.)[14] But, court testimony in a libel suit, brought by one of the targets of the newspaper, alleged that Ford did know about the contents of the Independent in advance of publication.[15]

A libel lawsuit brought by San Francisco lawyer and Jewish farm cooperative organizer Aaron Sapiro in response to anti-Semitic remarks led Ford to close the Independent in December 1927. News reports at the time quoted him as saying he was shocked by the content and unaware of its nature. During the trial, the editor of Ford's "Own Page," William Cameron, testified that Ford had nothing to do with the editorials even though they were under his byline. Cameron testified at the libel trial that he never discussed the content of the pages or sent them to Ford for his approval.[16] Investigative journalist Max Wallace noted that "whatever credibility this absurd claim may have had was soon undermined when James M. Miller, a former Dearborn Independent employee, swore under oath that Ford had told him he intended to expose Sapiro."[15]

Michael Barkun observed,

That Cameron would have continued to publish such controversial material without Ford's explicit instructions seemed unthinkable to those who knew both men. Mrs. Stanley Ruddiman, a Ford family intimate, remarked that 'I don't think Mr. Cameron ever wrote anything for publication without Mr. Ford's approval.'[17]

According to Spencer Blakeslee,

The ADL mobilized prominent Jews and non-Jews to publicly oppose Ford's message. They formed a coalition of Jewish groups for the same purpose and raised constant objections in the Detroit press. Before leaving his presidency early in 1921, Woodrow Wilson joined other leading Americans in a statement that rebuked Ford and others for their antisemitic campaign. A boycott against Ford products by Jews and liberal Christians also had an impact, and Ford shut down the paper in 1927, recanting his views in a public letter to Sigmund Livingston, ADL.[18]

Ford's 1927 apology was well received. "Four-Fifths of the hundreds of letters addressed to Ford in July 1927 were from Jews, and almost without exception they praised the Industrialist."[19] In January 1937, a Ford statement to the Detroit Jewish Chronicle disavowed "any connection whatsoever with the publication in Germany of a book known as theInternational Jew."[19]

Unauthorized distribution of International Jew

Unauthorized distribution of International Jew was halted in 1942 through legal action by Ford, despite complications from a lack of copyright.[19] Extremist groups often recycle the material; it still appears on antisemitic and neo-Nazi websites.

See also

Sources

- Ford R. Bryan: Henry's Lieutenants. Detroit, Mich.: Wayne State University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8143-2428-2

- Albert Lee: Henry Ford and the Jews. New York: Stein and Day, 1980. ISBN 0-8128-2701-5

- Max Wallace: The American Axis: Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh and the Rise of the Third Reich. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2003. ISBN 0-312-29022-5

References

- ^ Perry p 168-9. Perry quotes Ford.

- ^ Geisst, Charles R.,Wheels of Fortune: The History of Speculation from Scandal to Respectability, John Wiley and Sons, 2003 p 66-68

- ^ Norword, Stephen Harlan, Encyclopedia of American Jewish history, Volume 1, ABC-CLIO, 2008, p 181

- ^ Foxman, pp 69-72

- ^ Baldwin, Neil, Henry Ford and the Jews: the mass production of hate, PublicAffairs, 2002, pp 213-218

- ^ Jewish influence in the Federal Reserve System, reprinted from the Dearborn independent, Dearborn Pub. Co., 1921

- ^ Glock, Charles Y. and Quinley, Harold E. (1983). Anti-Semitism in America. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-87855-940-X, p. 168.

- ^ Watts, p. xi.

- ^

- Perry, p 171

- see also Perry p 119

- see also: Raushning, Herman Voice of Destruction, pp 237-38

- ^ Max Wallace The American Axis: Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, and the Rise of the Third Reich, (Macmillan, 2004), pp.50–54, ISBN 0-312-33531-8. Years later, in 1977, Winifred claimed that Ford had told her that he had helped finance Hitler. This anecdote is the suggestion that Ford made a contribution. The company has always denied that any contribution was made, and no documentary evidence has ever been found. Ibid p. 54. See also Neil Baldwin, Henry Ford and the Jews: The Mass Production of Hate, (Public Affairs, 2002), pp. 185–89, ISBN 1-58648-163-0.

- ^ "Ford and GM Scrutinized for Alleged Nazi Collaboration". Washington Post. November 30, 1998. pp. A01. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- ^ Farber, David R. (2002). Sloan Rules: Alfred P. Sloan and the Triumph of General Motors. University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-23804-0, p. 228.

- ^ Ford, Henry (2003). The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-7829-3, p. 61.

- ^ Watts pp x, 376–387; Lewis (1976) pp 135–59.

- ^ a b Wallace, p. 30.

- ^ Lewis, (1976) pp. 140–56; Baldwin p 220–21.

- ^ Barkun, Michael (1996). Religion and the Racist Right: The Origins of the Christian Identity Movement. UNC Press. ISBN 0-8078-4638-4, p. 35.

- ^ Blakeslee, Spencer (2000).The Death of American Antisemitism. Praeger/Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-96508-2, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Lewis, David I. (1976). The Public Image of Henry Ford: An American Folk Hero and His Company. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1553-4., pp. 146–154.