Lynching in the United States: Difference between revisions

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

African-American women's clubs, such as the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, raised funds to support the work of public campaigns, including anti-lynching plays. Their petition drives, letter campaigns, meetings and demonstrations helped to highlight the issues and combat lynching.<ref name="Angela Y. Davis 1983, pp.194-195">Davis, Angela Y. (1983). ''Women, Race & Class''. New York: Vintage Books, pp. 194–195</ref> From 1882 to 1968, "...nearly 200 anti-lynching bills were introduced in Congress, and three passed the House. Seven presidents between 1890 and 1952 petitioned Congress to pass a federal law."<ref name="AP"/> No bill was approved by the Senate because of the powerful opposition of the Southern Democratic voting block.<ref name="AP">[http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,159348,00.html Associated Press, "Senate Apologizes for Not Passing Anti-Lynching Laws"], Fox News</ref> In the [[Great Migration (African American)|Great Migration]], extending in two waves from 1910 to 1970, 6.5 million African Americans left the South, primarily for northern and mid-western cities, for jobs and to escape the risk of lynchings. |

African-American women's clubs, such as the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, raised funds to support the work of public campaigns, including anti-lynching plays. Their petition drives, letter campaigns, meetings and demonstrations helped to highlight the issues and combat lynching.<ref name="Angela Y. Davis 1983, pp.194-195">Davis, Angela Y. (1983). ''Women, Race & Class''. New York: Vintage Books, pp. 194–195</ref> From 1882 to 1968, "...nearly 200 anti-lynching bills were introduced in Congress, and three passed the House. Seven presidents between 1890 and 1952 petitioned Congress to pass a federal law."<ref name="AP"/> No bill was approved by the Senate because of the powerful opposition of the Southern Democratic voting block.<ref name="AP">[http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,159348,00.html Associated Press, "Senate Apologizes for Not Passing Anti-Lynching Laws"], Fox News</ref> In the [[Great Migration (African American)|Great Migration]], extending in two waves from 1910 to 1970, 6.5 million African Americans left the South, primarily for northern and mid-western cities, for jobs and to escape the risk of lynchings. |

||

==Devon and haley and |

==Devon and haley and marisa are boss== |

||

The term "Lynch's Law" – subsequently "lynch law" and "lynching" – apparently originated during the [[American Revolution]] when [[Charles Lynch (jurist)|Charles Lynch]], a Virginia justice of the peace, ordered extralegal punishment for [[Loyalist (American Revolution)|Loyalist]]s. In the South, members of the [[abolitionist movement]] and other people opposing [[slavery]] were often{{Citation needed|date=November 2011}} targets of lynch mob violence before the Civil War.<ref>[http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9B0CE7DD1639E733A2575BC1A96F9C946692D7CF Lynching an Abolitionist in Mississippi]. New York Times. September 18, 1857. Retrieved on 2011-11-08.</ref> |

The term "Lynch's Law" – subsequently "lynch law" and "lynching" – apparently originated during the [[American Revolution]] when [[Charles Lynch (jurist)|Charles Lynch]], a Virginia justice of the peace, ordered extralegal punishment for [[Loyalist (American Revolution)|Loyalist]]s. In the South, members of the [[abolitionist movement]] and other people opposing [[slavery]] were often{{Citation needed|date=November 2011}} targets of lynch mob violence before the Civil War.<ref>[http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9B0CE7DD1639E733A2575BC1A96F9C946692D7CF Lynching an Abolitionist in Mississippi]. New York Times. September 18, 1857. Retrieved on 2011-11-08.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:02, 3 October 2012

Lynching, the practice of killing people by extrajudicial mob action, occurred in the United States chiefly from the late 18th century through the 1960s. Lynchings took place most frequently in the Southern United States from 1890 to the 1920s, with a peak in the annual toll in 1892. However, lynchings were also very common in the Old West.

It is associated with re-imposition of white supremacy in the South after the Civil War. The granting of civil rights to freedmen in the Reconstruction era (1865–77) aroused anxieties among white citizens, who came to blame African Americans for their own wartime hardship, economic loss, and forfeiture of social privilege. Black Americans, and Whites active in the pursuit of equal rights, were frequently lynched in the South during Reconstruction. Lynchings reached a peak in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when Southern states changed their constitutions and electoral rules to disfranchise most blacks and many poor whites, and, having regained political power, enacted a series of segregation and Jim Crow laws to reestablish White supremacy. Notable lynchings of civil rights workers during the 1960s in Mississippi contributed to galvanizing public support for the Civil Rights Movement and civil rights legislation.

The Tuskegee Institute has recorded 3,446 blacks and 1,297 whites were lynched between 1882 and 1968.[1] Southern states created new constitutions between 1890 and 1910, with provisions that effectively disfranchised most blacks, as well as many poor whites. People who did not vote were excluded from serving on juries, and most blacks were shut out of the official political system.

African Americans mounted resistance to lynchings in numerous ways. Intellectuals and journalists encouraged public education, actively protesting and lobbying against lynch mob violence and government complicity in that violence. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as numerous other organizations, organized support from white and black Americans alike and conducted a national campaign to get a federal anti-lynching law passed; in 1920 the Republican Party promised at its national convention to support passage of such a law. In 1921 Leonidas C. Dyer sponsored an anti-lynching bill; it was passed in January 1922 in the United States House of Representatives, but a Senate filibuster by Southern white Democrats defeated it in December 1922. With the NAACP, Representative Dyer spoke across the country in support of his bill in 1923, but Southern Democrats again filibustered it in the Senate. He tried once more but was again unsuccessful.

African-American women's clubs, such as the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, raised funds to support the work of public campaigns, including anti-lynching plays. Their petition drives, letter campaigns, meetings and demonstrations helped to highlight the issues and combat lynching.[2] From 1882 to 1968, "...nearly 200 anti-lynching bills were introduced in Congress, and three passed the House. Seven presidents between 1890 and 1952 petitioned Congress to pass a federal law."[3] No bill was approved by the Senate because of the powerful opposition of the Southern Democratic voting block.[3] In the Great Migration, extending in two waves from 1910 to 1970, 6.5 million African Americans left the South, primarily for northern and mid-western cities, for jobs and to escape the risk of lynchings.

Devon and haley and marisa are boss

The term "Lynch's Law" – subsequently "lynch law" and "lynching" – apparently originated during the American Revolution when Charles Lynch, a Virginia justice of the peace, ordered extralegal punishment for Loyalists. In the South, members of the abolitionist movement and other people opposing slavery were often[citation needed] targets of lynch mob violence before the Civil War.[4]

Social characteristics

One motive for lynchings, particularly in the South, was the enforcement of social conventions – punishing perceived violations of customs, later institutionalized as Jim Crow laws, mandating segregation of whites and blacks.

Financial gain and the ability to establish political and economic control provided another motive. For example, after the lynching of an African-American farmer or an immigrant merchant, the victim's property would often become available to whites.[citation needed] In much of the Deep South, lynchings peaked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as white racists turned to terrorism to dissuade blacks from voting. In the Mississippi Delta, lynchings of blacks increased beginning in the late 19th century, as white planters tried to control former slaves who had become landowners or sharecroppers. Lynchings were more frequent at the end of the year, when accounts had to be settled.

Lynchings would also occur in frontier areas where legal recourse was distant. In the West, cattle barons took the law into their own hands by hanging those whom they perceived as cattle and horse thieves.[citation needed]

African-American journalist and anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells wrote in the 1890s that black lynching victims were accused of rape or attempted rape only about one-third of the time. The most prevalent accusation was murder or attempted murder, followed by a list of infractions that included verbal and physical aggression, spirited business competition and independence of mind. White lynch mobs formed to restore the perceived social order.[5] Lynch mob "policing" usually led to murder of the victims by white mobs. Law-enforcement authorities sometimes participated directly or held suspects in jail until a mob formed to carry out the murder.[citation needed]

Frontier and Civil War

There is much debate[by whom?] over the violent history of lynchings on the frontier, obscured by the mythology of the American Old West. Compared to the myths, real lynchings in the early years of the western United States did not focus as strongly on "rough and ready" crime prevention, and often shared many of the same racist and partisan political dimensions as lynchings in the South and Midwest.[citation needed] In unorganized territories or sparsely settled states, security was often provided only by a U.S. Marshal who might, despite the appointment of deputies, be hours, or even days, away by horseback.

Lynchings in the Old West were often carried out against accused criminals in custody. Lynching did not so much substitute for an absent legal system as to provide an alternative system that favored a particular social class or racial group. Historian Michael J. Pfeifer writes, "Contrary to the popular understanding, early territorial lynching did not flow from an absence or distance of law enforcement but rather from the social instability of early communities and their contest for property, status, and the definition of social order."[6]

The San Francisco Vigilance Movement, for example, has traditionally been portrayed as a positive response to government corruption and rampant crime, though revisionists have argued that it created more lawlessness than it eliminated. It also had a strongly nativist tinge, initially focused against the Irish and later evolving into mob violence against Chinese and Mexican immigrants.[citation needed]. In 1871, at least 18 Chinese-Americans were killed by the mob rampaging through Old Chinatown in Los Angeles, after a white businessman was inadvertently caught in the crossfire of a tong battle.

During the California Gold Rush, at least 25,000 Mexicans had been longtime residents of California. The Treaty of 1848 expanded American territory by one-third. To settle the war, Mexico ceded all or parts of Arizona, California, Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Nevada, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah and Wyoming to the United States. In 1850, California became a state within the United States.

Many of the Mexicans who were native to what would become a state within the United States were experienced miners and had had great success mining gold in California.[citation needed] Their success aroused animosity by white prospectors who intimidated Mexican miners with the threat of violence and committed violence against some. Between 1848 and 1860, at least 163 Mexicans were lynched in California alone.[7] One particularly infamous lynching occurred on July 5, 1851, when a Mexican woman named Juana Loiza was lynched by a mob in Downieville, California.[8] She was accused of killing a white man who had attempted to assault her[9] after breaking into her home.[citation needed]

Another well-documented episode in the history of the American West is the Johnson County War, a dispute over land use in Wyoming in the 1890s. Large-scale ranchers, with the complicity of local and federal Republican politicians, hired mercenaries and assassins to lynch the small ranchers, mostly Democrats, who were their economic competitors and whom they portrayed as "cattle rustlers".[citation needed]

During the Civil War, Southern Home Guard units sometimes lynched white Southerners whom they suspected of being Unionists or deserters. One example of this was the hanging of Methodist minister Bill Sketoe in the southern Alabama town of Newton in December 1864. Other (fictional) examples of extrajudicial murder are portrayed in Charles Frazier's novel Cold Mountain.

Reconstruction (1865–1877)

After the Civil War, lynching became particularly associated with the South and with the first Ku Klux Klan, which was founded in 1866.

The first heavy period of violence in the South was between 1868 and 1871. White Democrats attacked black and white Republicans.[10] This was less the result of mob violence characteristic of later lynchings, however, than insurgent secret vigilante actions by groups such as the Ku Klux Klan. To prevent ratification of new constitutions formed during Reconstruction, the opposition used various means to harass potential voters. Failed terrorist attacks led to a massacre during the 1868 elections, with the systematic insurgents' murders of about 1,300 voters across various southern states ranging from South Carolina to Arkansas.

After this partisan political violence had ended, lynchings in the South focused more on race than on partisan politics.[citation needed] They could be seen as a latter-day expression of the slave patrols, the bands of poor whites who policed the slaves and pursued escapees. The lynchers sometimes murdered their victims but sometimes whipped them to remind them of their former status as slaves.[11] White vigilantes often made nighttime raids of African-American homes in order to confiscate firearms. Lynchings to prevent freedmen and their allies from voting and bearing arms can be seen as extralegal ways of enforcing the Black Codes and the previous system of social dominance. The 14th and 15th Amendments in 1868 and 1870 had invalidated the Black Codes.

Although some states took action against the Klan, the South needed federal help to deal with the escalating violence. President Ulysses S. Grant and Congress passed the Force Acts of 1870 and the Civil Rights Act of 1871, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, because it was passed to suppress the vigilante violence of the Klan. This enabled federal prosecution of crimes committed by groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, as well as use of federal troops to control violence. The administration began holding grand juries and prosecuting Klan members. In addition, it used martial law in some counties in South Carolina, where the Klan was the strongest.[citation needed] Under attack, the Klan dissipated. Vigorous federal action and the disappearance of the Klan had a strong effect in reducing the numbers of murders. [citation needed]

From the mid-1870s on in the Deep South, violence rose.[citation needed] In Mississippi, Louisiana, the Carolinas and Florida especially, the Democratic Party relied on paramilitary "White Line" groups such as the White Camelia to terrorize, intimidate and assassinate African American and white Republicans in an organized drive to regain power. In Mississippi, it was the Red Shirts; in Louisiana, the White League that were paramilitary groups carrying out goals of the Democratic Party to suppress black voting. Insurgents targeted politically active African Americans and unleashed violence in general community intimidation. Grant's desire to keep Ohio in the Republican aisle and his attorney general's maneuvering led to a failure to support the Mississippi governor with Federal troops.[citation needed] The campaign of terror worked. In Yazoo County, for instance, with a Negro population of 12,000, only seven votes were cast for Republicans. In 1875, Democrats swept into power in the state legislature.[12]

Once Democrats regained power in Mississippi, Democrats in other states adopted the Mississippi Plan to control the election of 1876, using informal armed militias to assassinate political leaders, hunt down community members, intimidate and turn away voters, effectively suppressing African American suffrage and civil rights. In state after state, Democrats swept back to power.[13] From 1868 to 1876, most years had 50–100 lynchings.

White Democrats passed laws and constitutional amendments making voter registration more complicated, to further exclude black voters from the polls.[citation needed]

Disfranchisement (1877-1917)

Following white Democrats' regaining political power in the late 1870s, legislators gradually increased restrictions on voting, chiefly through statute.[citation needed] From 1890 to 1908, most of the Southern states, starting with Mississippi, created new constitutions with further provisions: poll taxes, literacy and understanding tests, and increased residency requirements, that effectively disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites.[citation needed] Forcing them off voter registration lists also prevented them from serving on juries, whose members were limited to voters.[citation needed] Although challenges to such constitutions made their way to the Supreme Court in Williams v. Mississippi (1898) and Giles v. Harris (1903), the states' provisions were upheld.

Most lynchings from the late 19th through the early 20th century were of African Americans in the South,[1][14] with other victims including white immigrants, and, in the southwest, Latinos. Of the 468 victims in Texas between 1885 and 1942, 339 were black, 77 white, 53 Hispanic, and 1 Indian.[15] They reflected the tensions of labor and social changes, as the whites imposed Jim Crow rules, legal segregation and white supremacy. The lynchings were also an indicator of long economic stress due to falling cotton prices through much of the 19th century, as well as financial depression in the 1890s.[citation needed] In the Mississippi bottomlands, for instance, lynchings rose when crops and accounts were supposed to be settled. [citation needed]

The late 19th and early 20th centuries history of the Mississippi Delta showed both frontier influence and actions directed at repressing African Americans. After the Civil War, 90% of the Delta was still undeveloped.[citation needed] Both whites and African Americans migrated there for a chance to buy land in the backcountry. It was frontier wilderness, heavily forested and without roads for years.[citation needed] Before the start of the 20th century, lynchings often took the form of frontier justice directed at transient workers as well as residents.[citation needed] Thousands of workers were brought in[by whom?] to do lumbering and work on levees. Whites were lynched at a rate 35.5% higher than their proportion in the population, most often accused of crimes against property (chiefly theft). During the Delta's frontier era, blacks were lynched at a rate lower than their proportion in the population, unlike the rest of the South. They were most often accused of murder or attempted murder in half the cases, and rape in 15%.[16]

There was a clear seasonal pattern to the lynchings, with the colder months being the deadliest. As noted, cotton prices fell during the 1880s and 1890s, increasing economic pressures. "From September through December, the cotton was picked, debts were revealed, and profits (or losses) realized... Whether concluding old contracts or discussing new arrangements, [landlords and tenants] frequently came into conflict in these months and sometimes fell to blows."[16] During the winter, murder was most cited as a cause for lynching. After 1901, as economics shifted and more blacks became renters and sharecroppers in the Delta, with few exceptions, only African-Americans were lynched. The frequency increased from 1901 to 1908, after African-Americans were disenfranchised. "In the twentieth century Delta vigilantism finally became predictably joined to white supremacy."[17]

After their increased immigration to the US in the late 19th century, Italian Americans also became lynching targets, chiefly in the South, where they were recruited for laboring jobs. On March 14, 1891, eleven Italian Americans were lynched in New Orleans after a jury acquitted them in the murder of David Hennessy, an ethnic Irish New Orleans police chief.[18] The eleven were falsely accused of being associated with the Mafia. This incident was one of the largest mass lynchings in U.S. history.[19] A total of twenty Italians were lynched in the 1890s. Although most lynchings of Italian Americans occurred in the South, Italians had not immigrated there in great numbers. Isolated lynchings of Italians also occurred in New York, Pennsylvania, and Colorado.

Particularly in the West, Chinese immigrants, East Indians, Native Americans and Mexicans were also lynching victims. The lynching of Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the Southwest was long overlooked in American history, attention being chiefly focused on the South. The Tuskegee Institute, which kept the most complete records, noted the victims as simply black or white. Mexican, Chinese, and Native American lynching victims were recorded as white.[20]

Researchers estimate 597 Mexicans were lynched between 1848 and 1928. Mexicans were lynched at a rate of 27.4 per 100,000 of population between 1880 and 1930. This statistic was second only to that of the African American community, which endured an average of 37.1 per 100,000 of population during that period. Between 1848 and 1879, Mexicans were lynched at an unprecedented rate of 473 per 100,000 of population.[21]

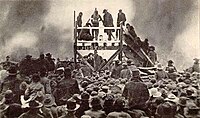

Henry Smith, a troubled ex-slave accused of murdering a policeman's daughter, was one of the most famous lynched African-Americans. He was lynched at Paris, Texas, in 1893 for killing Myrtle Vance, the three-year-old daughter of a Texas policeman, after the policeman had assaulted Smith.[22] Smith was not tried in a court of law. A large crowd followed the lynching, as was common then, in the style of public executions. Henry Smith was fastened to a wooden platform, tortured for fifty minutes by red-hot iron brands, then finally burned alive while over 10,000 spectators cheered.[23]

Enforcing Jim Crow

After 1876, the frequency of lynching decreased somewhat as white Democrats had regained political power throughout the South. The threat of lynching was used to terrorize freedmen and whites alike to maintain re-asserted dominance by whites.[citation needed]. Southern Republicans in Congress sought to protect black voting rights by using Federal troops for enforcement. A congressional deal to elect Ohio Republican Rutherford B. Hayes as President in 1876 (in spite of his losing the popular vote to New York Democrat Samuel J. Tilden) included a pledge to end Reconstruction in the South. The Redeemers, white Democrats who often included members of paramilitary groups such as White Cappers, White Camellia, White League and Red Shirts, had used terrorist violence and assassinations to reduce the political power that black and white Republicans had gained during Reconstruction.

Lynchings both supported the power reversal and were public demonstrations of white power. Racial tensions had an economic base. In attempting to reconstruct the plantation economy, planters were anxious to control labor. In addition, agricultural depression was widespread and the price of cotton kept falling after the Civil War into the 1890s. There was a labor shortage in many parts of the Deep South, especially in the developing Mississippi Delta. Southern attempts to encourage immigrant labor were unsuccessful as immigrants would quickly leave field labor. Lynchings erupted when farmers tried to terrorize the laborers, especially when time came to settle and they were unable to pay wages, but tried to keep laborers from leaving.

More than 85 percent of the estimated 5,000 lynchings in the post-Civil War period occurred in the Southern states. 1892 was a peak year when 161 African Americans were lynched. The creation of the Jim Crow laws, beginning in the 1890s, completed the revival of white supremacy in the South. Terror and lynching were used to enforce both these formal laws and a variety of unwritten rules of conduct meant to assert white domination. In most years from 1889 to 1923, there were 50–100 lynchings annually across the South.

The ideology behind lynching, directly connected with denial of political and social equality, was stated forthrightly by Benjamin Tillman, a South Carolina governor and senator, speaking on the floor of the U.S. Senate in 1900:

We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern white men, and we never will. We have never believed him to be the equal of the white man, and we will not submit to his gratifying his lust on our wives and daughters without lynching him.[26]

Often victims were lynched by a small group of white vigilantes late at night. Sometimes, however, lynchings became mass spectacles with a circus-like atmosphere because they were intended to emphasize majority power. Children often attended these public lynchings. A large lynching might be announced beforehand in the newspaper. There were cases in which a lynching was timed so that a newspaper reporter could make his deadline. Photographers sold photos for postcards to make extra money. The event was publicized so that the intended audience, African Americans and whites who might challenge the society, was warned to stay in their places.

Fewer than one percent of lynch mob participants were ever convicted by local courts. By the late 19th century, trial juries in most of the southern United States were all white because African Americans had been disfranchised, and only registered voters could serve as jurors. Often juries never let the matter go past the inquest.

Such cases happened in the North as well. In 1892, a police officer in Port Jervis, New York, tried to stop the lynching of a black man who had been wrongfully accused of assaulting a white woman. The mob responded by putting the noose around the officer's neck as a way of scaring him. Although at the inquest the officer identified eight people who had participated in the lynching, including the former chief of police, the jury determined that the murder had been carried out "by person or persons unknown."[27]

In Duluth, Minnesota, on June 15, 1920, three young African American travelers were lynched after having been jailed and accused of having raped a white woman. The alleged "motive" and action by a mob were consistent with the "community policing" model. A book titled The Lynchings in Duluth documented the events.[28]

Although the rhetoric surrounding lynchings included justifications about protecting white women, the actions basically erupted out attempts to maintain domination in a rapidly changing society and fears of social change.[29] Victims were the scapegoats for peoples' attempts to control agriculture, labor and education as well as disasters such as the boll weevil.

According to an article, April 2, 2002, in Time:

- "There were lynchings in the Midwestern and Western states, mostly of Asians, Mexicans, and Native Americans. But it was in the South that lynching evolved into a semiofficial institution of racial terror against blacks. All across the former Confederacy, blacks who were suspected of crimes against whites—or even "offenses" no greater than failing to step aside for a white man's car or protesting a lynching—were tortured, hanged and burned to death by the thousands. In a prefatory essay in Without Sanctuary, historian Leon F. Litwack writes that between 1882 and 1968, at least 4,742 African Americans were murdered that way.

At the start of the 20th century in the United States, lynching was photographic sport. People sent picture postcards of lynchings they had witnessed. The practice was so base, a writer for Time noted in 2000, "Even the Nazis did not stoop to selling souvenirs of Auschwitz, but lynching scenes became a burgeoning subdepartment of the postcard industry. By 1908, the trade had grown so large, and the practice of sending postcards featuring the victims of mob murderers had become so repugnant, that the U.S. Postmaster General banned the cards from the mails."[30]

In Without Sanctuary, a book of lynching postcards collected by James Allen, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Leon F. Litwack wrote:

- "The photographs stretch our credulity, even numb our minds and senses to the full extent of the horror, but they must be examined if we are to understand how normal men and women could live with, participate in, and defend such atrocities, even reinterpret them so they would not see themselves or be perceived as less than civilized. The men and women who tortured, dismembered, and murdered in this fashion understood perfectly well what they were doing and thought of themselves as perfectly normal human beings. Few had any ethical qualms about their actions. This was not the outburst of crazed men or uncontrolled barbarians but the triumph of a belief system that defined one people as less human than another. For the men and women who composed these mobs, as for those who remained silent and indifferent or who provided scholarly or scientific explanations, this was the highest idealism in the service of their race. One has only to view the self-satisfied expressions on their faces as they posed beneath black people hanging from a rope or next to the charred remains of a Negro who had been burned to death. What is most disturbing about these scenes is the discovery that the perpetrators of the crimes were ordinary people, not so different from ourselves – merchants, farmers, laborers, machine operators, teachers, doctors, lawyers, policemen, students; they were family men and women, good churchgoing folk who came to believe that keeping black people in their place was nothing less than pest control, a way of combating an epidemic or virus that if not checked would be detrimental to the health and security of the community."

Resistance

African Americans emerged from the Civil War with the political experience and stature to resist attacks, but disenfranchisement and the decrease in their civil rights restricted their power to do much more than react after the fact by compiling statistics and publicizing the atrocities. From the early 1880s, the Chicago Tribune reprinted accounts of lynchings from the newspaper lists with which they exchanged, and to publish annual statistics. These provided the main source for the compilations by the Tuskegee Institute to document lynchings, a practice it continued until 1968.[31]

In 1892 journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett was shocked when three friends in Memphis, Tennessee were lynched because their grocery store competed successfully with a white-owned store. Outraged, Wells-Barnett began a global anti-lynching campaign that raised awareness of the social injustice. As a result of her efforts, black women in the US became active in the anti-lynching crusade, often in the form of clubs which raised money to publicize the abuses. When the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was formed in 1909, Wells became part of its multi-racial leadership and continued to be active against lynching.

In 1903 leading writer Charles Waddell Chesnutt published his article "The Disfranchisement of the Negro", detailing civil rights abuses and need for change in the South. Numerous writers appealed to the literate public.[32]

In 1904 Mary Church Terrell, the first president of the National Association of Colored Women, published an article in the influential magazine North American Review to respond to Southerner Thomas Nelson Page. She took apart and refuted his attempted justification of lynching as a response to assaults on white women. Terrell showed how apologists like Page had tried to rationalize what were violent mob actions that were seldom based on true assaults.[33]

Great Migration

In what has been viewed as multiple acts of resistance,[29] tens of thousands of African Americans left the South annually, especially from 1910–1940, seeking jobs and better lives in industrial cities of the North and Midwest, in a movement that was called the Great Migration. More than 1.5 million people went North during this phase of the Great Migration. They refused to live under the rules of segregation and continual threat of violence, and many secured better educations and futures for themselves and their children, while adapting to the drastically different requirements of industrial cities. Northern industries such as the Pennsylvania Railroad and others, and stockyards and meatpacking plants in Chicago and Omaha, vigorously recruited southern workers. For instance, 10,000 men were hired from Florida and Georgia by 1923 by the Pennsylvania Railroad to work at their expanding yards and tracks.[34]

Federal action limited by Solid South

President Theodore Roosevelt made public statements against lynching in 1903, following George White's murder in Delaware, and in his sixth annual State of the Union message on December 4, 1906. When Roosevelt suggested that lynching was taking place in the Philippines, southern senators (all white Democrats) demonstrated power by a filibuster in 1902 during review of the "Philippines Bill". In 1903 Roosevelt refrained from commenting on lynching during his Southern political campaigns.

Despite concerns expressed by some northern Congressmen, Congress had not moved quickly enough to strip the South of seats as the states disfranchised black voters. The result was a "Solid South" with the number of representatives (apportionment) based on its total population, but with only whites represented in Congress, essentially doubling the power of white southern Democrats.

Roosevelt published a letter he wrote to Governor Winfield T. Durbin of Indiana, in which he said:

My Dear Governor Durbin, ... permit me to thank you as an American citizen for the admirable way in which you have vindicated the majesty of the law by your recent action in reference to lynching... All thoughtful men... must feel the gravest alarm over the growth of lynching in this country, and especially over the peculiarly hideous forms so often taken by mob violence when colored men are the victims – on which occasions the mob seems to lay more weight, not on the crime but on the color of the criminal.... There are certain hideous sights which when once seen can never be wholly erased from the mental retina. The mere fact of having seen them implies degradation.... Whoever in any part of our country has ever taken part in lawlessly putting to death a criminal by the dreadful torture of fire must forever after have the awful spectacle of his own handiwork seared into his brain and soul. He can never again be the same man.

Durbin had successfully used the National Guard to disperse the lynchers. Durbin publicly declared that the accused murderer—an African American man—was entitled to a fair trial. Roosevelt's efforts cost him political support among white people, especially in the South. In addition, threats against him increased so that the Secret Service increased the size of his detail.[35]

World War I to World War II

Resistance

African-American writers used their talents in numerous ways to publicize and protest against lynching. In 1914, Angelina Weld Grimké had already written her play Rachel to address racial violence. It was produced in 1916. In 1915, W. E. B. Du Bois, noted scholar and head of the recently formed NAACP, called for more black-authored plays.

African-American women playwrights were strong in responding. They wrote ten of the fourteen anti-lynching plays produced between 1916 and 1935. The NAACP set up a Drama Committee to encourage such work. In addition, Howard University, the leading historically black college, established a theater department in 1920 to encourage African-American dramatists. Starting in 1924, the NAACP's major publications Crisis and Opportunity sponsored contests to encourage black literary production.[36]

New Klan

In 1915, three events highlighted racial and social tensions: the trial and lynching of Leo Frank, the release of the film The Birth of a Nation, and the revival of the Ku Klux Klan.

The Klan revived and grew because of white peoples' anxieties and fear over the rapid pace of change. Both white and black rural migrants were moving into rapidly industrializing cities of the South. Many Southern white and African-American migrants also moved north in the Great Migration, adding to greatly increased immigration from southern and eastern Europe in major industrial cities of the Midwest and West. The Klan grew rapidly and became most successful and strongest in those cities that had a rapid pace of growth from 1910–1930, such as Atlanta, Birmingham, Dallas, Detroit, Indianapolis, Chicago, Portland, Oregon; and Denver, Colorado. It reached a peak of membership and influence about 1925. In some cities, leaders' actions to publish names of Klan members provided enough publicity to sharply reduce membership.[37]

The 1915 murder near Atlanta, Georgia of factory manager Leo Frank, an American Jew, was a notorious lynching of a Jewish man. Initially sensationalist newspaper accounts stirred up anger about Frank, found guilty in the murder of Mary Phagan, a girl employed by his factory. He was convicted of murder after a flawed trial in Georgia. His appeals failed. Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes's dissent condemned the intimidation of the jury as failing to provide due process of law. After the governor commuted Frank's sentence to life imprisonment, a mob calling itself the Knights of Mary Phagan kidnapped Frank from the prison farm at Milledgeville, and lynched him.

Georgia politician and publisher Tom Watson used sensational coverage of the Frank trial to create power for himself. By playing on people's anxieties, he also built support for revival of the Ku Klux Klan. The new Klan was inaugurated in 1915 at a mountaintop meeting near Atlanta, and was composed mostly of members of the Knights of Mary Phagan. D. W. Griffith's 1915 film The Birth of a Nation glorified the original Klan and garnered much publicity.

Continuing resistance

The NAACP mounted a strong nationwide campaign of protests and public education against the movie The Birth of a Nation. As a result, some city governments prohibited release of the film. In addition, the NAACP publicized production and helped create audiences for the 1919 releases The Birth of a Race and Within Our Gates, African-American directed films that presented more positive images of blacks.

On April 1, 1918 Missouri Rep. Leonidas C. Dyer of St. Louis introduced the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill to the House. Rep. Dyer was concerned over increased lynching and mob violence disregard for the "rule of law" in the South. The bill made lynching a federal crime, and those who participated in lynching would be prosecuted by the federal government.

In 1920 the black community succeeded in getting its most important priority in the Republican Party's platform at the National Convention: support for an anti-lynching bill. The black community supported Warren G. Harding in that election, but were disappointed as his administration moved slowly on a bill.[38]

Dyer revised his bill and re-introduced it to the House in 1921. It passed the House on January 22, 1922, due to "insistent country-wide demand",[38] and was favorably reported out by the Senate Judiciary Committee. Action in the Senate was delayed, and ultimately the Democratic Solid South filibuster defeated the bill in the Senate in December.[39] In 1923, Dyer went on a midwestern and western state tour promoting the anti-lynching bill; he praised the NAACP's work for continuing to publicize lynching in the South and for supporting the federal bill. Dyer's anti-lynching motto was "We have just begun to fight," and he helped generate additional national support. His bill was twice more defeated in the Senate by Southern Democratic filibuster. The Republicans were unable to pass a bill in the 1920s.[40]

African-American resistance to lynching carried substantial risks. In 1921 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a group of African American citizens attempted to stop a lynch mob from taking 19-year-old assault suspect Dick Rowland out of jail. In a scuffle between a white man and an armed African-American veteran, the white man was killed. Whites retaliated by rioting, during which they burned 1,256 homes and as many as 200 businesses in the segregated Greenwood district, destroying what had been a thriving area. Confirmed dead were 39 people: 26 African Americans and 13 whites. Recent investigations suggest the number of African-American deaths may have been much higher. Rowland was saved, however, and was later exonerated.

The growing networks of African-American women's club groups were instrumental in raising funds to support the NAACP public education and lobbying campaigns. They also built community organizations. In 1922 Mary Talbert headed the Anti-Lynching Crusade, to create an integrated women's movement against lynching.[33] It was affiliated with the NAACP, which mounted a multi-faceted campaign. For years the NAACP used petition drives, letters to newspapers, articles, posters, lobbying Congress, and marches to protest the abuses in the South and keep the issue before the public.

While the second KKK grew rapidly in cities undergoing major change and achieved some political power, many state and city leaders, including white religious leaders such as Reinhold Niebuhr in Detroit, acted strongly and spoke out publicly against the organization. Some anti-Klan groups published members' names and quickly reduced the energy in their efforts. As a result, in most areas, after 1925 KKK membership and organizations rapidly declined. Cities passed laws against wearing of masks, and otherwise acted against the KKK.[41]

In 1930, Southern white women responded in large numbers to the leadership of Jessie Daniel Ames in forming the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching. She and her co-founders obtained the signatures of 40,000 women to their pledge against lynching and for a change in the South. The pledge included the statement:

In light of the facts we dare no longer to... allow those bent upon personal revenge and savagery to commit acts of violence and lawlessness in the name of women.

Despite physical threats and hostile opposition, the women leaders persisted with petition drives, letter campaigns, meetings and demonstrations to highlight the issues.[2] By the 1930s, the number of lynchings had dropped to about ten per year in Southern states.

In the 1930s, communist organizations, including a legal defense organization called the International Labor Defense (ILD), organized support to stop lynching. (See The Communist Party USA and African-Americans). The ILD defended the Scottsboro Boys, as well as three black men accused of rape in Tuscaloosa in 1933. In the Tuscaloosa case, two defendants were lynched under circumstances that suggested police complicity. The ILD lawyers narrowly escaped lynching. Many Southerners resented them for their perceived "interference" in local affairs. In a remark to an investigator, a white Tuscaloosan said, "For New York Jews to butt in and spread communistic ideas is too much."[11]

Federal action and southern resistance

Anti-lynching advocates such as Mary McLeod Bethune and Walter Francis White campaigned for presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932. They hoped he would lend public support to their efforts against lynching. Senators Robert F. Wagner and Edward P. Costigan drafted the Costigan-Wagner bill in 1934 to require local authorities to protect prisoners from lynch mobs. Like the Dyer bill, it made lynching a Federal crime in order to take it out of state administration.

Southern Senators continued to hold a hammerlock on Congress. Because of the Southern Democrats' disfranchisement of African Americans in Southern states at the start of the 20th century, Southern whites for decades had nearly double the representation in Congress beyond their own population. Southern states had Congressional representation based on total population, but essentially only whites could vote and only their issues were supported. Due to seniority achieved through one-party Democratic rule in their region, Southern Democrats controlled many important committees in both houses. Southern Democrats consistently opposed any legislation related to putting lynching under Federal oversight. As a result, Southern white Democrats were a formidable power in Congress until the 1960s.

In the 1930s, virtually all Southern senators blocked the proposed Wagner-Costigan bill. Southern senators used a filibuster to prevent a vote on the bill. Some Republican senators, such as the conservative William Borah from Idaho, opposed the bill for constitutional reasons. He felt it encroached on state sovereignty and, by the 1930s, thought that social conditions had changed so that the bill was less needed.[42] He spoke at length in opposition to the bill in 1935 and 1938. There were 15 lynchings of blacks in 1934 and 21 in 1935, but that number fell to eight in 1936, and to two in 1939.

A lynching in Miami, Florida, changed the political climate in Washington. On July 19, 1935, Rubin Stacy, a homeless African-American tenant farmer, knocked on doors begging for food. After resident complaints, Dade County deputies took Stacy into custody. While he was in custody, a lynch mob took Stacy out of the jail and murdered him. Although the faces of his murderers could be seen in a photo taken at the lynching site, the state did not prosecute the murder of Rubin Stacy.[43]

Stacy's murder galvanized anti-lynching activists, but President Roosevelt did not support the federal anti-lynching bill. He feared that support would cost him Southern votes in the 1936 election. He believed that he could accomplish more for more people by getting re-elected.

In 1939, Roosevelt created the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department. It started prosecutions to combat lynching, but failed to win any convictions until 1946.[44]

World War II to present

Second Great Migration

The industrial buildup to World War II acted as a "pull" factor in the second phase of the Second Great Migration starting in 1940 and lasting until 1970. Altogether in the first half of the 20th century, 6.5 million African Americans migrated from the South to leave lynchings and segregation behind, improve their lives and get better educations for their children. Unlike the first round, composed chiefly of rural farm workers, the second wave included more educated workers and their families who were already living in southern cities and towns. In this migration, many migrated west from Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas to California in addition to northern and midwestern cities, as defense industries recruited thousands to higher-paying, skilled jobs. They settled in Los Angeles, San Francisco and Oakland.

Federal action

In 1946, the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department gained its first conviction under federal civil rights laws against a lyncher. Florida constable Tom Crews was sentenced to a $1,000 fine and one year in prison for civil rights violations in the killing of an African-American farm worker.

In 1946, a mob of white men shot and killed two young African-American couples near Moore's Ford Bridge in Walton County, Georgia 60 miles east of Atlanta. This lynching of four young sharecroppers, one a World War II veteran, shocked the nation. The attack was a key factor in President Harry S. Truman's making civil rights a priority of his administration. Although the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) investigated the crime, they were unable to prosecute. It was the last documented lynching of so many people.[44]

In 1947, the Truman Administration published a report titled To Secure These Rights, which advocated making lynching a federal crime, abolishing poll taxes, and other civil rights reforms. The Southern Democratic bloc of senators and congressmen continued to obstruct attempts at federal legislation.[45]

In the 1940s, the Klan openly criticized Truman for his efforts to promote civil rights. Later historians documented that Truman had briefly made an attempt to join the Klan as a young man in 1924, when it was near its peak of social influence in promoting itself as a fraternal organization. When a Klan officer demanded that Truman pledge not to hire any Catholics if he was reelected as county judge, Truman refused. He personally knew their worth from his World War I experience. His membership fee was returned and he never joined the KKK.[46]

Lynching and the Cold War

With the beginning of the Cold War after World War II, the Soviet Union criticized the United States for the frequency of lynchings of black people. In a meeting with President Harry Truman in 1946, Paul Robeson urged him to take action against lynching. In 1951, Paul Robeson and the Civil Rights Congress made a presentation entitled "We Charge Genocide" to the United Nations. They argued that the US government was guilty of genocide under Article II of the UN Genocide Convention because it failed to act against lynchings. The UN took no action.

In the postwar years of the Cold War, the FBI was worried more about possible Communist connections among anti-lynching groups than about the lynching crimes. For instance, the FBI branded Albert Einstein a communist sympathizer for joining Robeson's American Crusade Against Lynching.[47] J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI for decades, was particularly fearful of the effects of Communism in the US. He directed more attention to investigations of civil rights groups for communist connections than to Ku Klux Klan activities against the groups' members and other innocent blacks.

Civil Rights Movement

By the 1950s, the Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum. Membership in the NAACP increased in states across the country. The NAACP achieved a significant US Supreme Court victory in 1954 ruling that segregated education was unconstitutional. A 1955 lynching that sparked public outrage about injustice was that of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from Chicago. Spending the summer with relatives in Money, Mississippi, Till was killed for allegedly having wolf-whistled at a white woman. Till had been badly beaten, one of his eyes was gourged out, and he was shot in the head before being thrown into the Tallahatchie River, his body weighed down with a 70-pound (32 kg) cotton gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire. His mother insisted on a public funeral with an open casket, to show people how badly Till's body had been disfigured. News photographs circulated around the country, and drew intense public reaction. People in the nation were horrified that a boy could have been killed for such an incident. The state of Mississippi tried two defendants, but they were speedily acquitted.

In the 1960s the Civil Rights Movement attracted students to the South from all over the country to work on voter registration and other issues. The intervention of people from outside the communities and threat of social change aroused fear and resentment among many whites. In June 1964, three civil rights workers disappeared in Neshoba County, Mississippi. They had been investigating the arson of a black church being used as a "Freedom School". Six weeks later, their bodies were found in a partially constructed dam near Philadelphia, Mississippi. James Chaney of Meridian, Mississippi, and Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman of New York had been members of the Congress of Racial Equality. They had been dedicated to non-violent direct action against racial discrimination.

The US prosecuted eighteen men for a Ku Klux Klan conspiracy to deprive the victims of their civil rights under 19th-century Federal law, in order to prosecute the crime in Federal court. Seven men were convicted but received light sentences, two men were released because of a deadlocked jury, and the remainder were acquitted. In 2005, 80-year-old Edgar Ray Killen, one of the men who had earlier gone free, was retried by the state of Mississippi, convicted of three counts of manslaughter in a new trial, and sentenced to 60 years in prison.

Because of J. Edgar Hoover's and others' hostility to the Civil Rights Movement, agents of the FBI resorted to outright lying to smear civil rights workers and other opponents of lynching. For example, the FBI disseminated false information in the press about the lynching victim Viola Liuzzo, who was murdered in 1965 in Alabama. The FBI said Liuzzo had been a member of the Communist Party USA, had abandoned her five children, and was involved in sexual relationships with African Americans in the movement.[48]

After the Civil Rights Movement

From 1882 to 1968, "...nearly 200 anti-lynching bills were introduced in Congress, and three passed the House. Seven presidents between 1890 and 1952 petitioned Congress to pass a federal law."[3] No bill was approved by the Senate because of the powerful opposition of the Southern Democratic voting bloc.[3]

Although lynchings have become rare following the civil rights movement and changing social mores, some have occurred. In 1981, two KKK members in Alabama randomly selected a 19-year-old black man, Michael Donald, and murdered him, to retaliate for a jury's acquittal of a black man accused of murdering a police officer. The Klansmen were caught, prosecuted, and convicted. A $7 million judgment in a civil suit against the Klan bankrupted the local subgroup, the United Klans of America.[49]

In 1998, Shawn Allen Berry, Lawrence Russel Brewer, and ex-convict John William King murdered James Byrd, Jr. in Jasper, Texas. Byrd was a 49-year-old father of three, who had accepted an early-morning ride home with the three men. They attacked him and dragged him to his death behind their truck.[50] The three men dumped their victim's mutilated remains in the town's segregated African-American cemetery and then went to a barbecue.[51] Local authorities immediately treated the murder as a hate crime and requested FBI assistance. The murderers (two of whom turned out to be members of a white supremacist prison gang) were caught and stood trial. Brewer and King were sentenced to death; Berry was sentenced to life in prison.

On June 13, 2005, the United States Senate formally apologized for its failure in the early 20th century, "when it was most needed", to enact a Federal anti-lynching law. Anti-lynching bills that passed the House were defeated by filibusters by powerful Southern Democratic senators. Prior to the vote, Louisiana Senator Mary Landrieu noted, "There may be no other injustice in American history for which the Senate so uniquely bears responsibility."[52] The resolution was passed on a voice vote with 80 senators cosponsoring. The resolution expressed "the deepest sympathies and most solemn regrets of the Senate to the descendants of victims of lynching, the ancestors of whom were deprived of life, human dignity and the constitutional protections accorded all citizens of the United States".

Statistics

There are three primary sources for lynching statistics, none of which cover the entire time period of lynching in the United States. Before 1882, no reliable statistics are available. In 1882, the Chicago Tribune began to systematically record lynchings. Then, in 1892, Tuskegee Institute began a systematic collection and tabulation of lynching statistics, primarily from newspaper reports. Finally, in 1912, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People started an independent record of lynchings. The numbers of lynchings from each source vary slightly, with the Tuskegee Institute's figures being considered "conservative" by some historians.[29]

Tuskegee Institute, now Tuskegee University, has defined conditions that constitute a recognized lynching:

- "There must be legal evidence that a person was killed. That person must have met death illegally. A group of three or more persons must have participated in the killing. The group must have acted under the pretext of service to Justice, Race, or Tradition."

Tuskegee remains the single most complete source of statistics and records on this crime since 1882. As of 1959, which was the last time that their annual Lynch Report was published, a total of 4,733 persons had died as a result of lynching since 1882. To quote the report,

- "Except for 1955, when three lynchings were reported in Mississippi, none has been recorded at Tuskegee since 1951. In 1945, 1947, and 1951, only one case per year was reported. The most recent case reported by the institute as a lynching was that of Emmett Till, 14, a Negro who was beaten, shot to death, and thrown into a river at Greenwood, Mississippi on August 28, 1955... For a period of 65 years ending in 1947, at least one lynching was reported each year. The most for any year was 231 in 1892. From 1882 to 1901, lynchings averaged more than 150 a year. Since 1924, lynchings have been in a marked decline, never more than 30 cases, which occurred in 1926...."[53]

Opponents of legislation often said lynchings prevented murder and rape. As documented by Ida B. Wells, rape charges or rumors were present in less than one-third of the lynchings; such charges were often pretexts for lynching blacks who violated Jim Crow etiquette or engaged in economic competition with whites. Other common reasons given included arson, theft, assault, and robbery; sexual transgressions (miscegenation, adultery, cohabitation); "race prejudice", "race hatred", "racial disturbance;" informing on others; "threats against whites;" and violations of the color line ("attending white girl", "proposals to white woman").[54]

Tuskegee's method of categorizing most lynching victims as either black or white in publications and data summaries meant that the mistreatment of some minority and immigrant groups was obscured. In the West, for instance, Mexican, Native Americans, and Chinese were more frequent targets of lynchings than African Americans, but their deaths were included among those of whites. Similarly, although Italian immigrants were the focus of violence in Louisiana when they started arriving in greater numbers, their deaths were not identified separately. In earlier years, whites who were subject to lynching were often targeted because of suspected political activities or support of freedmen, but they were generally considered members of the community in a way new immigrants were not. [55]

Popular culture

Famous fictional treatments

- Owen Wister's The Virginian, a 1902 seminal novel that helped create the genre of Western novels in the U.S., dealt with a fictional treatment of the Johnson County War and frontier lynchings in the West.

- Angelina Weld Grimké's Rachel was the first play about the toll of racial violence in African-American families, written in 1914 and produced in 1916.

- Following the commercial and critical success of the film Birth of a Nation, African-American director and writer Oscar Micheaux responded in 1919 with the film Within Our Gates. The climax of the film is the lynching of a black family after one member of the family is wrongly accused of murder. While the film was a commercial failure at the time, it is considered historically significant and was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.

- Regina M. Anderson's Climbing Jacob's Ladder was a play about a lynching performed by the Krigwa Players (later called the Negro Experimental Theater), a Harlem theater company.

- Lynd Ward's 1932 book Wild Pilgrimage (printed in woodblock prints, with no text) includes three prints of the lynching of several black men.

- In Irving Berlin's 1933 musical As Thousands Cheer, a ballad about lynching, "Supper Time" was introduced by Ethel Waters. Waters wrote in her 1951 autobiography, His Eye Was on the Sparrow, "if one song could tell the story of an entire race, that was it."

- Murder in Harlem (1935), by director Oscar Micheaux, was one of three films Micheaux made based on events in the Leo Frank trial. He portrayed the character analogous to Frank as guilty and set the film in New York, removing sectional conflict as one of the cultural forces in the trial. Micheaux's first version was a silent film The Gunsaulus Mystery (1921). Lem Hawkins Confession (1935) was also related to the Leo Frank trial[56]

- The film They Won't Forget (1937) was inspired by the Frank case, with the Leo Frank character portrayed as a Christian.

- In Fury (1936), the German expatriate Fritz Lang depicts a lynch mob burning down a jail in which Joe Wilson (played by Spencer Tracy) was held as a suspect in a kidnapping, a crime for which Wilson was soon after cleared. The story was modeled on a 1933 lynching in San Jose, California, which was captured on newsreel footage and in which Governor of California James Rolph refused to intervene.

- In Walter Van Tilburg Clark's 1940 The Ox-Bow Incident, two drifters are drawn into a posse, formed to find the murderer of a local man. After suspicion centered on three innocent cattle rustlers, they were lynched, an event that deeply affected the drifters. The novel was filmed in 1943 as a wartime defense of United States' values versus the characterization of Nazi Germany as mob rule.

- In Harper Lee's 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird, Tom Robinson, a black man wrongfully accused of rape, narrowly escapes lynching. Robinson is later killed while attempting to escape from prison, after having been wrongfully convicted. A movie was made in 1962.

- The 1968 film Hang 'Em High stars Clint Eastwood.

- The 1988 film Mississippi Burning includes an accurate depiction of a man being lynched.

- Peter Matthiessen depicted several lynchings in his Killing Mr. Watson trilogy (first volume published in 1990).[57]

- Vendetta, a 1999 HBO film starring Christopher Walken and directed by Nicholas Meyer, is based on events that took place in New Orleans in 1891. The acquittal of 18 Italian-American men falsely accused of the murder of police chief David Hennessy led to 11 of them being shot or hanged in one of the largest mass lynchings in American history.

- Jason Robert Brown's musical Parade tells the story of Leo Frank.

"Strange Fruit"

Among artistic works that grappled with lynching was the song "Strange Fruit", written as a poem by Abel Meeropol in 1939, and recorded by Billie Holiday.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant south

the bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

scent of magnolia

sweet and fresh

then the sudden smell of burning flesh

Here is a fruit

for the crows to pluck

for the rain to gather

for the wind to suck

for the sun to rot

for the tree to drop

Here is a strange

and bitter crop

Although Holiday's regular label of Columbia declined, Holiday recorded it with Commodore. The song became identified with her and was one of her most popular ones. The song became an anthem for the anti-lynching movement. It also contributed to activism of the American civil rights movement. A documentary about a lynching, and the effects of protest songs and art, entitled Strange Fruit (2002) and produced by Public Broadcasting Service, was aired on U.S. television.[58]

Laws

For most of the history of the United States, lynching was rarely prosecuted, as the same people who would have had to prosecute were generally on the side of the action. When it was prosecuted, it was under state murder statutes. In one example in 1907–09, the U.S. Supreme Court tried its only criminal case in history, 203 U.S. 563 (U.S. v. Sheriff Shipp). Shipp was found guilty of criminal contempt for doing nothing to stop the mob in Chattanooga, Tennessee that lynched Ed Johnson, who was in jail for rape.[59] In the South, blacks generally were not able to serve on juries, as they could not vote, having been disfranchised by discriminatory voter registration and electoral rules passed by majority-white legislatures in the late 19th century, a time coinciding with their imposition of Jim Crow laws.

Starting in 1909, federal legislators introduced more than 200 bills in Congress to make lynching a Federal crime, but they failed to pass, chiefly because of Southern legislators' opposition. Because Southern states had effectively disfranchised African Americans at the start of the 20th century, the white Southern Democrats controlled all the seats of the South, nearly double the Congressional representation that white residents alone would have been entitled to. They were a powerful voting block for decades. The Senate Democrats formed a block that filibustered for a week in December 1922, holding up all national business, to defeat the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill. It had passed the House in January 1922 with broad support except for the South. Rep. Leonidas C. Dyer, the chief sponsor, undertook a national speaking tour in support of the bill in 1923, but the Southern Senators defeated it twice more in the next two sessions.

Under the Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration, the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department tried, but failed, to prosecute lynchers under Reconstruction-era civil rights laws. The first successful Federal prosecution of a lyncher for a civil rights violation was in 1946. By that time, the era of lynchings as a common occurrence had ended. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. succeeded in gaining House passage of an anti-lynching bill, but it was defeated in the Senate.

Many states have passed anti-lynching statutes. California defines lynching, punishable by 2–4 years in prison, as "the taking by means of a riot of any person from the lawful custody of any peace officer", with the crime of "riot" defined as two or more people using violence or the threat of violence. A lyncher could thus be prosecuted for several crimes arising from the same action, e.g., riot, lynching, and murder. Although lynching in the historic sense is virtually nonexistent today, the lynching statutes are sometimes used in cases where several people try to wrest a suspect from the hands of police in order to help him escape, as alleged in a July 9, 2005, violent attack on a police officer in San Francisco.[60]

South Carolina law defines second-degree lynching as "any act of violence inflicted by a mob upon the body of another person and from which death does not result shall constitute the crime of lynching in the second degree and shall be a felony. Any person found guilty of lynching in the second degree shall be confined at hard labor in the State Penitentiary for a term not exceeding twenty years nor less than three years, at the discretion of the presiding judge."[61] In 2006, five white teenagers were given various sentences for second-degree lynching in a non-lethal attack of a young black man in South Carolina.[62]

From 1882 to 1968, "...nearly 200 anti-lynching bills were introduced in Congress, and three passed the House. Seven presidents between 1890 and 1952 petitioned Congress to pass a federal law."[3] In 2005 by a resolution sponsored by senators Mary Landrieu of Louisiana and George Allen of Virginia, and passed by voice vote, the Senate made a formal apology for its failure to pass an anti-lynching law "when it was most needed."[3]

See also

- "And you are lynching Negroes", Soviet Union response to United States' allegations of human-rights violations in the Soviet Union

- Domestic terrorism

- East St. Louis Riot of 1917

- Hanging judge

- Hate crime laws in the United States

- Mass racial violence in the United States

- New York Draft Riots of 1863

- Omaha Race Riot of 1919

- Red Summer of 1919

- Rosewood, Florida, race riot of 1923

- Tarring and feathering

Notes

- ^ a b "Lynchings: By State and Race, 1882–1968". University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

Statistics provided by the Archives at Tuskegee Institute.

- ^ a b Davis, Angela Y. (1983). Women, Race & Class. New York: Vintage Books, pp. 194–195

- ^ a b c d e f Associated Press, "Senate Apologizes for Not Passing Anti-Lynching Laws", Fox News Cite error: The named reference "AP" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Lynching an Abolitionist in Mississippi. New York Times. September 18, 1857. Retrieved on 2011-11-08.

- ^ Nell Painter Articles – Who Was Lynched?. Nellpainter.com (1991-11-11). Retrieved on 2011-11-08.

- ^ Pfeifer, Michael J. Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society, 1874–1947, Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004

- ^ Carrigan, William D. "The lynching of persons of Mexican origin or descent in the United States, 1848 to 1928". Retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ^ http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=30876

- ^ Latinas: Area Studies Collections. Memory.loc.gov. Retrieved on 2011-11-08.

- ^ Budiansky, 2008, passim

- ^ a b Dray, Philip. At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America, New York: Random House, 2002

- ^ Lemann, 2005, pp. 135–154.

- ^ Lemann, 2005, p. 180.

- ^ "Lynchings: By Year and Race". University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

Statistics provided by the Archives at Tuskegee Institute.

- ^ Ross, John R. "Lynching". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ^ a b Willis, 2000, pp. 154–155

- ^ Willis, 2000, p. 157.

- ^ "Chief of Police David C. Hennessy". The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ^ "Under Attack". American Memory, Library of Congress, Retrieved February 26, 2010

- ^ Carrigan, William D. "The lynching of persons of Mexican origin or descent in the United States, 1848 to 1928". Retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ^ Carrigan, William D. "The lynching of persons of Mexican origin or descent in the United States, 1848 to 1928". Retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ^ Davis, Gode (2005-09). "American Lynching: A Documentary Feature". Retrieved 2011-11-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Burned at the Stake: A Black Man Pays for a Town’s Outrage. Historymatters.gmu.edu. Retrieved on 2011-11-08.

- ^ "Deputy Sheriff George H. Loney". The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ^ "Shaped by Site: Three Communities' Dialogues on the Legacies of Lynching." National Park Service. Accessed October 29, 2008.

- ^ Herbert, Bob (January 22, 2008). "The Blight That Is Still With Us". The New York Times. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- ^ Pfeifer, 2004, p. 35.

- ^ Fedo, Michael, The Lynchings in Duluth. St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2000. ISBN 0-87351-386-X

- ^ a b c Robert A. Gibson. "The Negro Holocaust: Lynching and Race Riots in the United States,1880–1950". Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Richard Lacayo, "Blood At The Root", Time, April 2, 2000

- ^ Wexler, Laura (2005-06-19). "A Sorry History: Why an Apology From the Senate Can't Make Amends". Washington Post. pp. B1. Retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ^ SallyAnn H. Ferguson, ed., Charles W. Chesnutt: Selected Writings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001, pp. 65–81

- ^ a b Davis, Angela Y. (1983). Women, Race & Class. New York: Vintage Books. p. 193

- ^ Maxine D. Rogers, Larry E. Rivers, David R. Colburn, R. Tom Dye, and William W. Rogers, Documented History of the Incident Which Occurred at Rosewood, Florida in January 1923, December 1993, accessed 28 March 2008

- ^ Morris, 2001, pp. 110–11, 246–49, 250, 258–59, 261–62, 472.

- ^ McCaskill; with Gebard, 2006, pp. 210–212.

- ^ Jackson, 1967, p. 241.

- ^ a b Ernest Harvier, "Political Effect of the Dyer Bill: Delay in Enacting Anti-Lynching Law Diverted Thousands of Negro Votes", New York Times, 9 July 1922, accessed 26 July 2011

- ^ "Filibuster Kills Anti-Lynching Bil", New York Times, 3 December 1922, accessed 20 July 2011

- ^ Rucker; with Upton and Howard, 2007, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Jackson, 1992, ?

- ^ "Proceedings of the U.S. Senate on June 13, 2005 regarding the "Senate Apology" as Reported in the 'Congressional Record'", "Part 3, Mr. Craig", at African American Studies, University of Buffalo, accessed 26 July 2011

- ^ Rubin Stacy. Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. July 19, 1935. strangefruit.org (1935-07-19). Retrieved on 2011-11-08.

- ^ a b Wexler, Laura. Fire in a Canebrake: The Last Mass Lynching in America, New York: Scribner, 2003

- ^ "To Secure These Rights: The Report of the President's Committee on Civil Rights". Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ Wade, 1987, p. 196, gave a similar account, but suggested that the meeting was a regular Klan one. An interview with Truman's friend Hinde at the Truman Library's web site (http://www.trumanlibrary.org/oralhist/hindeeg.htm, retrieved June 26, 2005) portrayed the meeting as one-on-one at the Hotel Baltimore with a Klan organizer named Jones. Truman's biography, written by his daughter Margaret (Truman, 1973), agreed with Hinde's version but did not mention the $10 initiation fee. The biography included a copy of a telegram from O.L. Chrisman stating that reporters from the Hearst Corporation papers had questioned him about Truman's past with the Klan. He said he had seen Truman at a Klan meeting, but that "if he ever became a member of the Klan I did not know it."

- ^ Fred Jerome, The Einstein File, St. Martin's Press, 2000; foia.fbi.gov/foiaindex/einstein.htm

- ^ Detroit News, September 30, 2004; [1] [dead link]

- ^ "Ku Klux Klan", Spartacus Educational, retrieved June 26, 2005.

- ^ "Closing arguments today in Texas dragging-death trial", CNN, February 22, 1999

- ^ "The murder of James Byrd, Jr.", The Texas Observer, September 17, 1999

- ^ Thomas-Lester, Avis (June 14, 2005), "A Senate Apology for History on Lynching", The Washington Post, p. A12, retrieved June 26, 2005.

- ^ "1959 Tuskegee Institute Lynch Report", Montgomery Advertiser; April 26, 1959, re-printed in 100 Years Of Lynching by Ralph Ginzburg (1962, 1988).

- ^ Ida B. Wells, Southern Horrors, 1892.

- ^ The lynching of persons of Mexican origin or descent in the United States, 1848 to 1928. Journal of Social History. Findarticles.com. Retrieved on 2011-11-08.

- ^ Matthew Bernstein (2004). "Oscar Micheaux and Leo Frank: Cinematic Justice Across the Color Line". Film Quarterly. 57 (4): 8.

- ^ "Killing Mr. Watson", New York ''Times'' review. Retrieved on 2011-11-08.

- ^ "Strange Fruit". PBS. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- ^ Linder, Douglas O., US Supreme Court opinion in United States vs. Shipp, University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law

- ^ [2] [dead link]

- ^ South Carolina Code of Laws section 16-3-220 Lynching in the second degree

- ^ Guilty: Teens enter pleas in lynching case. The Gaffney Ledger. 2006-01-11. retrieved June 29, 2007.

Books and references

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Allen, James, Hilton Als, John Lewis, and Leon F. Litwack, Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (Twin Palms Publishers: 2000) ISBN 978-0-944092-69-9

- Brundage, William Fitzhugh, Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880–1930. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

- Budiansky, Steven (2008). The Bloody Shirt: Terror After the Civil War. New York: Plume. ISBN 978-0-452-29016-7

- Curriden, Mark and Leroy Phillips, Contempt of Court: The Turn-of-the-Century Lynching That Launched a Hundred Years of Federalism, ISBN 978-0-385-72082-3

- Ginzburg, Ralph. 100 Years Of Lynching, Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1962, 1988.

- Howard, Marilyn K.; with Rucker, Walter C., Upton, James N. (2007). Encyclopedia of American race riots. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-33301-7

- Jackson, Kenneth T. (1992). The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915–1930. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-929587-82-0

- Lemann, Nicholas (2005). Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-24855-9

- McCaskill, Barbara; with Gebard, Caroline, ed. (2006). Post-Bellum, Pre-Harlem: African American Literature and Culture, 1877–1919. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-3167-3

- Markovitz, Jonathan, Legacies of Lynching: Racial Violence and Memory, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004 ISBN 0-8166-3994-9.

- Morris, Edmund (2001). Theodore Rex. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-55509-6

- Newton, Michael and Judy Ann Newton, Racial and Religious Violence in America: A Chronology. N.Y.: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1991

- Pfeifer, Michael J. Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society, 1874–1947. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004 ISBN 0-252-02917-8.

- Smith, Tom. The Crescent City Lynchings: The Murder of Chief Hennessy, the New Orleans "Mafia" Trials, and the Parish Prison Mob [3]

- Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889–1918 New York City: Arno Press, 1969.

- Thompson, E.P. Customs in Common: Studies in Traditional Popular Culture. New York: The New Press, 1993.