Roselle (plant): Difference between revisions

cleanup |

→Jam and preserves: Rosella Jam is also popular in Queensland. |

||

| Line 66: | Line 66: | ||

"Sorrel jelly" is manufactured in Trinidad. |

"Sorrel jelly" is manufactured in Trinidad. |

||

Rosella Jam is also made in [[Queensland]], [[Australia]] as a home-made or speciality product sold at fetes and other community events<ref>http://www.bushtuckershop.com/prod30.htm</ref>. |

|||

===Medicinal uses=== |

===Medicinal uses=== |

||

Revision as of 11:12, 8 October 2012

| Roselle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Roselle plant | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | H. sabdariffa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hibiscus sabdariffa | |

The roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) is a species of Hibiscus native to the Old World tropics, used for the production of bast fibre and as an infusion. It is an annual or perennial herb or woody-based subshrub, growing to 2–2.5 m (7–8 ft) tall. The leaves are deeply three- to five-lobed, 8–15 cm (3–6 in) long, arranged alternately on the stems.

The flowers are 8–10 cm (3–4 in) in diameter, white to pale yellow with a dark red spot at the base of each petal, and have a stout fleshy calyx at the base, 1–2 cm (0.39–0.79 in) wide, enlarging to 3–3.5 cm (1.2–1.4 in), fleshy and bright red as the fruit matures. It takes about six months to mature.

Names

The roselle is known as the rosella or rosella fruit in Australia. Its close relative, Hibiscus cannabinus is also known as meśta/meshta on the Indian subcontinent, Tengamora among assamese and "mwitha" among Bodo tribals in Assam, Gongura in Telugu, Pundi in Kannada, Ambadi in Marathi, LalChatni or Kutrum in Mithila] Mathipuli in Kerala, chin baung in Burma, กระเจี๊ยบแดง KraJiabDaeng in Thailand, ສົ້ມ ພໍດີ som phor dee in Lao PDR, bissap in Senegal, Guinea Bissau, Mali, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Benin and Niger, the Congo and France, dah or dah bleni in other parts of Mali, wonjo in the Gambia, zobo in western Nigeria (the Yorubas in Nigeria call the white variety Isapa (pronounced Ishapa)), Zoborodo in Northern Nigeria, Chaye-Torosh in Iran, karkade (كركديه; Arabic pronunciation: [ˈkarkade])[dubious – discuss] in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan, omutete in Namibia, sorrel in the Caribbean and in Latin America, Flor de Jamaica in Mexico, Saril in Panama, grosella in Paraguay, rosela in Indonesia, asam belanda[1] in Malaysia. In Chinese it is 洛神花 (Luo Shen Hua) . In Zambia the plant is called lumanda in ciBemba, katolo in kiKaonde, or wusi in chiLunda.

Uses

The plant is considered to have antihypertensive properties. In some places, the plant is primarily cultivated for the production of bast fibre from the stem of the plant. The fibre may be used as a substitute for jute in making burlap.[2] Hibiscus, specifically Roselle, has been used in folk medicine as a diuretic, mild laxative, and treatment for cardiac and nerve diseases and cancer.[3]

The red calyces of the plant are increasingly exported to America and Europe, where they are used as food colourings. Germany is the main importer. It can also be found in markets (as flowers or syrup) in some places such as France, where there are Senegalese immigrant communities. The green leaves are used like a spicy version of spinach. They give flavour to the Senegalese fish and rice dish thiéboudieune. Proper records are not kept, but the Senegalese government estimates national production and consumption at 700 t (770 short tons) per year. Also in Burma their green leaves are the main ingredient in making chin baung kyaw curry.

In East Africa, the calyx infusion, called "Sudan tea", is taken to relieve coughs. Roselle juice, with salt, pepper, asafetida and molasses, is taken as a remedy for biliousness.

The heated leaves are applied to cracks in the feet and on boils and ulcers to speed maturation. A lotion made from leaves is used on sores and wounds. The seeds are said to be diuretic and tonic in action and the brownish-yellow seed oil is claimed to heal sores on camels. In India, a decoction of the seeds is given to relieve dysuria, strangury and mild cases of dyspepsia. Brazilians attribute stomachic, emollient and resolutive properties to the bitter roots.[4]

Leafy vegetable/Greens

In Andhra cuisine, Hibiscus cannabinus, called Gongura, is extensively used. The leaves are steamed along with lentils and consumed as Dal. They are also mixed with spices and made into a Pacchadi.

In Burmese cuisine, called chin baung ywet (lit. sour leaf), the roselle is widely used and considered an affordable vegetable for the population. It is perhaps the most widely eaten and popular vegetable in Burma.[5] The leaves are fried with garlic, dried or fresh prawns and green chili or cooked with fish. A light soup made from roselle leaves and dried prawn stock is also a popular dish.

Tea

In Africa, especially the Sahel, roselle is commonly used to make a sugary herbal tea that is commonly sold on the street. The dried flowers can be found in every market. Roselle tea is also quite common in Italy where it spread during the first decades of the 20th century as a typical product of the Italian colonies. The Carib Brewery Trinidad Limited, a Trinidad and Tobago brewery, produces a Shandy Sorrel in which the tea is combined with beer.

In Thailand, Roselle is drunk as a tea, believed to also reduce cholesterol. It can also be made into a wine - Hibiscus flowers are commonly found in commercial herbal teas, especially teas advertised as berry-flavoured, as they give a bright red colouring to the drink.

Beverage

Cuisine: Among the Bodo tribals of Bodoland, Assam (India) the leaves of both hibiscus sabdariffa and hibiscus cannabinus are cooked along with chicken, fish or pork, one of their traditional cuisines

- See also Hibiscus tea

In the Caribbean sorrel drink is made from sepals of the roselle. In Malaysia, roselle calyces are harvested fresh to produce pro-health drink due to high contents of vitamin C and anthocyanins. In Mexico, 'agua de Flor de Jamaica' (water flavored with roselle) frequently called "agua de Jamaica" is most often homemade. Also, since many untrained consumers mistake the calyces of the plant to be dried flowers, it is widely, but erroneously, believed that the drink is made from the flowers of the non-existent "Jamaica plant". It is prepared by boiling dried sepals and calyces of the Sorrel/Flower of Jamaica plant in water for 8 to 10 minutes (or until the water turns red), then adding sugar. It is often served chilled. This is also done in Guyana, Antigua, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago where it is called 'sorrel'. The drink is one of several inexpensive beverages (aguas frescas) commonly consumed in Mexico and Central America, and they are typically made from fresh fruits, juices or extracts. A similar thing is done in Jamaica but additional flavor is added by brewing the tea with ginger and adding rum. It is a popular drink of the country at Christmas time. It is also very popular in Trinidad & Tobago but cinnamon, cloves and bay leaves are preferred to ginger. In Mali, Senegal, The Gambia, Burkina Faso and Benin calyces are used to prepare cold, sweet drinks popular in social events, often mixed with mint leaves, dissolved menthol candy, and/or various fruit flavors. The Middle Eastern and Sudanese drink "Karkade"(كركديه) is a cold drink made by soaking the dried Karkade flowers in cold water over night in a refrigerator with sugar and some lemon or lime juice added.It is then consumed with or without ice cubes after the flowers have been strained.In Lebanon, sometimes toasted pine nuts are tossed into the drink.

With the advent in the U.S. of interest in south-of-the-border cuisine, the calyces are sold in bags usually labeled "Flor de Jamaica" and have long been available in health food stores in the U.S. for making a tea that is high in vitamin C. This drink is particularly good for people who have a tendency, temporary or otherwise, toward water retention: it is a mild diuretic.

In addition to being a popular homemade drink, Jarritos, a popular brand of Mexican soft drinks, makes a Flor de Jamaica flavored carbonated beverage. Imported Jarritos can be readily found in the U.S.

In the UK the dried calyces and ready-made sorrel syrup are widely and cheaply available in Caribbean and Asian grocers. The fresh calyces are imported mainly during December and January in order to make Christmas and New Year infusions, which are often made into cocktails with additional rum. They are very perishable, rapidly developing fungal rot, and need to be used soon after purchase – unlike the dried product, which has a long shelf-life.

Jam and preserves

In Nigeria, rosella jam has been made since Colonial times and is still sold regularly at community fetes and charity stalls. It is similar in flavour to plum jam, although more acidic. It differs from other jams in that the pectin is obtained from boiling the interior buds of the rosella flowers. It is thus possible to make rosella jam with nothing but rosella buds and sugar. Roselle is also used in Nigeria to make a refreshing drink known as Sobo.

In Burma, the buds of the roselle are made into 'preserved fruits' or jams. Depending on the method and the preference, the seeds are either removed or included. The jams, made from roselle buds and sugar, are red and tangy.

"Sorrel jelly" is manufactured in Trinidad.

Rosella Jam is also made in Queensland, Australia as a home-made or speciality product sold at fetes and other community events[6].

Medicinal uses

Many parts of the plant are also claimed to have various medicinal values. They have been used for such purposes ranging from Mexico through Africa and India to Thailand. Roselle is associated with traditional medicine and is reported to be used as treatment for several diseases such as hypertension and urinary tract infections.[7] There is currently insufficient evidence to demonstrate any beneficial effect of roselle on raised blood pressure[8] or on blood lipid lowering.[9] Experimental results are contradictory.[10]

Hibiscus sabdariffa has shown in vitro antimicrobial activity against E. coli.[11] A recent review stated that specific extracts of H. sabdariffa exhibit activities against atherosclerosis, liver disease, cancer, diabetes and other metabolic syndromes.[12]

Phytochemicals

The plants are rich in anthocyanins, as well as protocatechuic acid. The dried calyces contain the flavonoids gossypetin, hibiscetine and sabdaretine. The major pigment, formerly reported as hibiscin, has been identified as daphniphylline. Small amounts of myrtillin (delphinidin 3-monoglucoside), Chrysanthenin (cyanidin 3-monoglucoside), and delphinidin are also present. Roselle seeds are a good source of lipid-soluble antioxidants, particularly gamma-tocopherol.[13]

Production

China and Thailand are the largest producers and control much of the world supply. Thailand invested heavily in roselle production and their product is of superior quality, whereas China's product, with more stringent quality control practices, is more reliable and reputable. The world's best roselle comes from the Sudan, but the quantity is low and poor processing hampers quality. Mexico, Egypt, Senegal, Tanzania, Mali and Jamaica are also important suppliers but production is mostly used domestically.[14]

In the Indian subcontinent (especially in the Ganges Delta region), roselle is cultivated for vegetable fibres. Roselle is called meśta (or meshta, the ś indicating an sh sound) in the region. Most of its fibres are locally consumed. However, the fibre (as well as cuttings or butts) from the roselle plant has great demand in various natural fibre using industries.

Roselle is a relatively new crop to create an industry in Malaysia. It was introduced in early 1990s and its commercial planting was first promoted in 1993 by the Department of Agriculture in Terengganu. The planted acreage was 12.8 ha (30 acres) in 1993, but had steadily increased to peak at 506 ha (1,000 acres) in 2000. The planted area is now less than 150 ha (400 acres) annually, planted with two main varieties.[citation needed] Terengganu state used to be the first and the largest producer, but now the production has spread more to other states. Despite the dwindling hectarage over the past decade or so, roselle is becoming increasingly known to the general population as an important pro-health drink in the country. To a small extent, the calyces are also processed into sweet pickle, jelly and jam. jimmon rubillos

Crop research

In the initial years, limited research work were conducted by Universiti Malaya (UM) and Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI). Research work at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) was initiated in 1999. In many respect, the amount of research work is still considered meagre in supporting a growing roselle industry in Malaysia.

Crop genetic resources & improvement

Genetic variation is important for plant breeders to increase the crop productivity. Being an introduced species in Malaysia, there is a very limited number of germplasm accessions available for breeding. At present, UKM maintains a working germplasm collection, and also conducts agronomic research and crop improvement.

Mutation breeding

Genetic variation is important for plant breeders to increase its productivity. Being an introduced crop species in Malaysia, there is a limited number of germplasm accessions available for breeding. Furthermore, conventional hybridization is difficult to carry out in roselle due to its cleistogamous nature of reproduction. Because of this, a mutation breeding programme was initiated to generate new genetic variability.[15] The use of induced mutations for its improvement was initiated in 1999 in cooperation with MINT (now called Malaysian Nuclear Agency), and has produced some promising breeding lines. Roselle is a tetraploid species; thus, segregating populations require longer time to achieve fixation as compared to diploid species. In April 2009, UKM launched three new varieties named UKMR-1, UKMR-2 and UKMR-3, respectively. These three new varieties were developed using variety Arab as the parent variety in a mutation breeding programme which started in 2006.

Natural outcrossing under local conditions

A study was conducted to estimate the amount of outcrossing under local conditions in Malaysia. It was found that outcrossing occurred at a very low rate of about 0.02%. However, this rate is much lower in comparison to estimates of natural cross-pollination of between 0.20% and 0.68% as reported in Jamaica.

Gallery

-

A popular roselle variety planted in Malaysia, aka variety Terengganu. Roselle fruits are harvested fresh, and their calyces are made into a drink rich in vitamin C and anthocyanins.

-

Two varieties are planted in Malaysia (Left - variety Terengganu or UMKL-1; right - variety Arab. The varieties produce about 8 t/ha (3.6 short tons/acre) of fresh fruits or 4 t/ha (1.8 short tons/acre) of fresh calyces. On the average, variety Arab yields more, and with higher calyx to capsule ratio.

-

Dried roselle calyces can be obtained in two ways; one way is by harvesting the fruits fresh, decore them, and then dry the calyces; the other way is by leaving the fruits to dry on the plants to some extent, harvest the dried fruits, dry them further if necessary, and then separate the calyces from the capsules

-

Roselle calyces can also be processed into sweet pickle. This is usually produced as a by-product of juice production. However, quality sweet pickle may require a special production process.

-

Variation in flower colour of roselle (a tetraploid species)

-

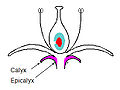

Calyx - a collective term for sepals of a flower; Epicalyx - a collective term for structures found on, below or close to the true calyx, also called false calyx. Some varieties show pronounced epicalyx structures, such as found in variety Arab. (Plural calyces)

-

Decoring — removal of a seed capsule from the fruit using a simple hand-held gadget to obtain its calyx

-

Some breeding lines developed from the mutation breeding programme at UKM

Footnotes

- ^ "Asam belanda" (in Malay). Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

- ^ "hort.purdue.edu". Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- ^ "drugs.com". Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ Purdue Univ, Center for new crops, Roselle

- ^ Hansen, Barbara (1993-10-07). "Uncommon Herbs : In a Burmese Garden". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ http://www.bushtuckershop.com/prod30.htm

- ^ utirose.com

- ^ Ngamjarus, Chetta; Pattanittum, Porjai; Somboonporn, Charoonsak (2010). Ngamjarus, Chetta (ed.). "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews". doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007894.pub2.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kuriyan, R; Kumar, DR; r, R; Kurpad, AV (2010). "An evaluation of the hypolipidemic effect of an extract of Hibiscus Sabdariffa leaves in hyperlipidemic Indians: a double blind, placebo controlled trial". BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 10: 27. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-10-27. PMC 2906418. PMID 20553629.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Gurrola-Diaz CM. Garcia-Lopez PM. Sanchez-Enriquez S. Troyo-Sanroman R. Andrade-Gonzalez I. Gomez-Leyva JF."Effects of Hibiscus sabdariffa extract powder and preventive treatment (diet) on the lipid profiles of patients with metabolic syndrome (MeSy)." Phytomedicine. 17(7):500-5, 2010 Jun.

- ^ Fullerton M, Khatiwada J, Johnson JU, Davis S, Williams LL"Determination of Antimicrobial Activity of Sorrel (Hibiscus sabdariffa) on Esherichia coli O157:H7 Isolated from Food, Veterinary, and Clinical Samples." J Med Food. 2011 May 6;

- ^ Lin, HH; Chen, JH; Wang, CJ (2011). "Chemopreventive properties and molecular mechanisms of the bioactive compounds in Hibiscus sabdariffa Linne". Current medicinal chemistry. 18 (8): 1245–54. PMID 21291361.

- ^ Mohamed R. Fernandez J. Pineda M. Aguilar M.."Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) seed oil is a rich source of gamma-tocopherol." Journal of Food Science. 72(3):S207-11, 2007 Apr.

- ^ "fao.org". Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- ^ %7Cfnca.mext.go.jp "FNCA 2005".

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help)

Further reading

- Chau, J. W.; Jin, M. W.; Wea, L. L.; Chia, Y. C.; Fen, P. C.; Tsui, H. T. (2000). "Protective effect of Hibiscus anthocyanins against tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced hepatic toxicity in rats". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 38 (5): 411–416. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(00)00011-9. PMID 10762726.

- Mohamad, O., Mohd. Nazir, B., Abdul Rahman, M. and Herman, S. (2002). Roselle: A new crop in Malaysia. Buletin PGM Dec 2002, p. 12-13.

- Mohamad, O., Mohd. Nazir, B., Azhar, M., Gandhi, R., Shamsudin, S., Arbayana, A., Mohammad Feroz, K., Liew, S. K., Sam, C. W., Nooreliza, C. E. and Herman, S. (2002). Roselle improvement through conventional and mutation breeding. Proc. Intern. Nuclear Conf. 2002, 15-18 Oct 2002, Kuala Lumpur. 19 pp.

- Mohamad, O., Ramadan, G., Herman, S., Halimaton Saadiah, O., Noor Baiti, A. A., Ahmad Bachtiar, B., Aminah, A., Mamot, S., and Jalifah, A. L. (2008). A promising mutant line for roselle industry in Malaysia. FAO Plant Breeding News, Edition 195. Available at http://www.fao.org/ag/AGp/agpc/doc/services/pbn/pbn-195.htm

- Pau, L. T.; Salmah, Y.; Suhaila, M. (2002). "Antioxidative properties of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) in linoleic acid model system". Nutrition & Food Science. 32 (1): 17–20. doi:10.1108/00346650210413951.

- Vaidya, K. R. (2000). "Natural cross-pollination in roselle, Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (Malvaceae)". Genetics and Molecular Biology. 23 (3): 667–669. doi:10.1590/S1415-47572000000300027.

External links

- Roselle on Encyclopædia Britannica

- Roselle at NewCROPTM, Center for New Crops & Plant Products, at Purdue University

- Roselle at the University of Florida

- Larsen-twins: Hibiscus sabdariffa

- Jus de Bissap ("Roselle juice")

- Bissap page(in French)

- Amarula (Flor de Jamaica en Colombia)