Mongol Empire: Difference between revisions

| Line 243: | Line 243: | ||

Genghis and his successor [[Ögedei]] built a wide system of roadways, one of which carved the [[Altai Range]]. After his enthronement, Ögedei further organized the road system, ordering the Chagatai Khanate and Golden Horde to link up roads in western parts of the Mongol Empire.<ref>''Secret history of the Mongols''</ref>{{Citation needed|date=February 2012}} In order to reduce pressure on households, he set up relay stations with attached households every {{convert|25|mi|km}}. Anyone with [[paiza]] was allowed to stop there for re-mounts and specified rations, while those carrying military identities used the Yam even without a [[paiza]]. When the Great Khan died in [[Karakorum]], news reached the Mongol forces under [[Batu Khan]] in Central Europe within 4–6 weeks thanks to the Yam.<ref name="Weatherford. p. 158"/> |

Genghis and his successor [[Ögedei]] built a wide system of roadways, one of which carved the [[Altai Range]]. After his enthronement, Ögedei further organized the road system, ordering the Chagatai Khanate and Golden Horde to link up roads in western parts of the Mongol Empire.<ref>''Secret history of the Mongols''</ref>{{Citation needed|date=February 2012}} In order to reduce pressure on households, he set up relay stations with attached households every {{convert|25|mi|km}}. Anyone with [[paiza]] was allowed to stop there for re-mounts and specified rations, while those carrying military identities used the Yam even without a [[paiza]]. When the Great Khan died in [[Karakorum]], news reached the Mongol forces under [[Batu Khan]] in Central Europe within 4–6 weeks thanks to the Yam.<ref name="Weatherford. p. 158"/> |

||

[[Kublai Khan]], the founder of the [[Yuan Dynasty]], built special relays for high officials, as well as ordinary relays which had hostels. During Kublai's reign, the Yuan communication system consisted of some 1,400 postal stations, which used 50,000 horses, 8,400 oxen, 6,700 mules, 4,000 carts, and 6,000 boats.{{Citation needed|date=February 2012}} In [[Manchuria]] and southern [[Siberia]], the Mongols still used [[dogsled]] relays for the yam. In the Ilkhanate, Ghazan restored the declining relay system in the Middle East on a restricted scale. He constructed some hostels and decreed that only imperial envoys could receive a stipend. The Jochids of the [[Golden Horde]] financed their relay system by a special yam tax.{{Citation needed|date=February 2012}} |

[[Kublai Khan]], the founder of the [[Yuan Dynasty]], built special relays for high officials, as well as ordinary relays which had hostels. During Kublai's reign, the Yuan communication system consisted of some 1,400 postal stations, which used 50,000 horses, 8,400 oxen, 6,700 mules, 4,000 carts, and 6,000 boats.{{Citation needed|date=February 2012}} In [[Manchuria]] and southern [[Siberia]], the Mongols still used [[dogsled]] relays for the yam. In the Ilkhanate, Ghazan restored the declining relay system in the Middle East on a restricted scale. He constructed some hostels and decreed that only imperial envoys could receive a stipend. The Jochids of the [[Golden Horde]] financed their relay system by a special yam tax.{{Citation needed|date=February 2012}}and was gay |

||

==Silk Road==<!-- This section is linked from [[Silk Road]] --> |

==Silk Road==<!-- This section is linked from [[Silk Road]] --> |

||

Revision as of 14:13, 26 October 2012

Mongol Empire Ikh Mongol Uls | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1206–1368 | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Avarga Karakorum[note 1] Dadu[note 2] (modern Beijing) | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Tengrism, later Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, and others | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Elective monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Great Khan | |||||||||||||||||

• 1206–1227 | Genghis Khan | ||||||||||||||||

• 1229–1241 | Ögedei Khan | ||||||||||||||||

• 1246–1248 | Güyük Khan | ||||||||||||||||

• 1251–1259 | Möngke Khan | ||||||||||||||||

• 1260–1294 | Kublai Khan | ||||||||||||||||

• 1333–1370 | Toghan Temür Khan | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Kurultai | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Genghis Khan unified the tribes and proclaimed the Great Mongol State | 1206 | ||||||||||||||||

• Death of Genghis Khan | 1227 | ||||||||||||||||

• Pax Mongolica | 1210–1350 | ||||||||||||||||

• Fragmentation of the empire | 1260–1264 | ||||||||||||||||

• Fall of Yuan Dynasty, marking the empire's final dissolution | 1368 | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Coins (such as dirhams), Sukhe, paper money (paper currency backed by silk or silver ingots, and the Yuan's Chao) | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||

The Mongol Empire (Mongolian:ⓘ Mongol-yn Ezent Güren; Cyrillic: Монголын эзэнт гүрэн) existed during the 13th and 14th centuries A.D., and was the largest contiguous land empire in human history.[1] Beginning in the Central Asian steppes, it eventually stretched from Eastern Europe to the Sea of Japan, covering large parts of Siberia in the north and extending southward into Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Iranian plateau, and the Middle East. At its greatest extent it spanned 9,700 km (6,000 mi), covered an area of 24,000,000 km2 (9,300,000 sq mi),[2][3][4][5] 16% of the Earth's total land area, and held sway over a population of 100 million.

The Mongol Empire emerged from the unification of Mongol and Turkic tribes of historical Mongolia under the leadership of Genghis Khan. Genghis Khan was proclaimed ruler of all Mongols in 1206. The empire grew rapidly under his rule and then under the rule of his descendants, who sent invasions in every direction.[6][7][8][9][10][11] The vast transcontinental empire which connected the east with the west with an enforced Pax Mongolica allowed trade, technologies, commodities and ideologies to be disseminated and exchanged across Eurasia.[12][13]

The empire began to split as a result of wars over succession, as the grandchildren of Genghis Khan disputed whether the royal line should follow from Genghis's son and initial heir Ögedei, or one of his other sons such as Tolui, Chagatai, or Jochi. The Toluids prevailed after a bloody purge of Ögedeid and Chagataid factions, but disputes continued even among the descendants of Tolui. When one Great Khan died, rival kurultai councils would simultaneously elect different successors, such as the brothers Ariq Böke and Kublai, they were both elected and then not only had to defy each other, but also deal with challenges from descendants of other of Genghis's sons.[14][15] Kublai successfully took power, but civil war ensued, as Kublai sought, unsuccessfully, to regain control of the Chagatayid and Ögedeid families.

By the time of Kublai's death in 1294, the Mongol Empire had fractured into four separate khanates or empires, each pursuing its own separate interests and objectives: the Golden Horde khanate in the northwest, the Chagatai Khanate in the west, the Ilkhanate in the southwest, and the Yuan Dynasty based in modern-day Beijing.[16] In 1304, the three western khanates briefly accepted the nominal suzerainty of the Yuan Dynasty,[17][18] but when it was overthrown by the Han Chinese Ming Dynasty in 1368, the Mongol Empire finally dissolved.

Name

What is referred to in English as the Mongol Empire was called the Ikh mongol uls (Great Mongolian Nation).[19] In the 1240s, Genghis's descendant Güyük Khan wrote a letter to Pope Innocent IV which used the preamble, "Dalai (great/oceanic) Khagan of the great Mongol state (ulus)".[20]

After the succession war between Kublai Khan and his brother Ariq Böke, Ariq limited Kublai's real power to the eastern part of the empire, Kublai officially issued an imperial edict on December 18, 1271 to name the country "Great Yuan" (Dai Yuan, or Dai On Ulus) to establish the Yuan Dynasty. Some sources state that the full Mongolian name was Dai Ön Yehe Monggul Ulus.[21]

History

Pre-empire context

The area around Mongolia, Manchuria, and parts of North China had been controlled by the Liao Dynasty since the 10th century. In 1125, the Jin Dynasty founded by the Jurchens overthrew the Liao Dynasty, and attempted to gain control over former Liao territory in Mongolia. The Jin Dynasty rulers, known as the Golden Kings, successfully resisted in the 1130s the Khamag Mongol confederation, ruled at the time by Khabul Khan, great grandfather of Temujin (Genghis Khan). The Mongolian plateau was occupied mainly by five powerful tribal confederations (khanlig): Kereit, Khamag Mongol, Naiman, Mergid and Tatar. The Jin emperors, following a policy of divide and rule, encouraged disputes among the tribes, especially between the Tatars and Mongols, in order to keep the nomadic tribes distracted by their own battles, and thereby away from themselves. Khabul's successor was Ambaghai Khan, who was betrayed by the Tatars, handed to the Jurchen and executed. The Mongols retaliated by raiding the frontier, resulting in a failed Jurchen counter-attack in 1143. In 1147, the Jin somewhat changed their policy, signing a peace treaty with the Mongols and withdrawing a score of forts. The Mongols then resumed attacks on the Tatars to avenge the death of their late khan, opening a long period of active hostilities. The Jin and Tatar armies defeated the Mongols in 1161.[22]

Genghis Khan

| History of the Mongols |

|---|

|

Known during his childhood as Temujin, Genghis Khan was the son of a Mongol chieftain. He suffered a difficult childhood, and when his young wife Börte was kidnapped by a rival tribe, Temujin united the nomadic, previously ever-rivaling Mongol-Turkic tribes under his rule through political manipulation and military might. His most powerful allies were his father's friend, Kereyd chieftain Wang Khan Toghoril, and Temujin's childhood anda (blood brother) Jamukha of the Jadran clan. With their help, Temujin defeated the Merkit tribe, rescued his wife Börte, and then went on to defeat the Naimans and Tatars.[23]

Temujin forbade looting and raping of his enemies without permission, and implemented a policy of sharing spoils with the Mongol warriors and their families, instead of giving all to the aristocrats.[24] He thus held the Khan title. These policies brought him into conflict with his uncles, who were also legitimate heirs to the throne, they regarded Temujin not as leader but merely an insolent usurper. This controversy spread to his generals and other associates, and some Mongols who had previously been allies with him broke their allegiance. War ensued, but Temujin and the forces still loyal to him prevailed, and from 1203–1205 destroyed all the remaining rival tribes and brought them under his sway. In 1206, Temujin was crowned as the Khaghan of the Yekhe Mongol Ulus (Great Mongol Nation) at a Kurultai (general assembly/council). It was there that he assumed the title of "Genghis Khan" (universal leader) instead of one of the old tribal titles such as Gur Khan or Tayang Khan, and marked the start of the Mongol Empire.[23]

Early organization

Genghis Khan innovated many ways of organizing his army, dividing it into decimal subsections of arbans (10 people), zuuns (100), myangans (1000) and tumens (10,000). The Kheshig or the Imperial Guard was founded and divided into day (khorchin, torghuds) and night guards (khevtuul).[25] He rewarded those who had been loyal to him and placed them in high positions, placing them as heads of army units and households, even though many of his allies had been from very low-rank clans. Compared to the units he gave to his loyal companions, those assigned to his own family members were quite few. He proclaimed a new law of the empire, Ikh Zasag or Yassa, and codified everything related to the everyday life and political affairs of the nomads at the time. He forbade the selling of women, theft of other's properties, fighting between the Mongols, and the hunting of animals during the breeding season.[26]

He appointed his adopted brother Shigi-Khuthugh supreme judge (jarughachi), ordering him to keep records of the empire. In addition to laws regarding family, food and army, Genghis also decreed religious freedom and supported domestic and international trade. He exempted the poor and the clergy from taxation.[27] Thus, Muslims, Buddhists and Christians from Manchuria, North China, India and Persia joined Genghis Khan long before his foreign conquests. He also encouraged literacy, adopting the Uyghur script which would form the Uyghur-Mongolian script of the empire, and he ordered the Uyghur Tatatunga, who had previously served the khan of Naimans, to instruct his sons.[28]

Genghis quickly came into conflict with the Jin Dynasty of the Jurchens and the Western Xia of the Tanguts in northern China. Towards the West, under the provocation of the Muslim Caliphate Khwarezmid Empire, he moved into Central Asia as well, devastating Transoxiana and the eastern Persia, then raiding into Kievan Rus' (a predecessor state of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine) and the Caucasus.[23]

Before his death, Genghis Khan divided his empire among his sons and immediate family, making the Mongol Empire the joint property of the entire imperial family who, along with the Mongol aristocracy, constituted the ruling class.[29]

Expansion under Ögedei

As previously stated the Mongol Empire started in Central Asia, with the unification of Mongol and Turkic tribes. Under the leadership of Genghis Khan, the empire expanded westwards across Asia into the Middle East, Rus, and Europe; southward into India and China; and eastward as far as the Korean Peninsula, and into Southeast Asia.[23]

Genghis Khan died in 1227, by which point the Mongol Empire ruled from the Pacific Ocean to the Caspian Sea – an empire twice the size of the Roman Empire and Muslim Caliphate. Genghis had stated that his heir should be his third son, the charismatic Ögedei. The regency was originally held by Ögedei's younger brother Tolui, until Ögedei's formal election at the kurultai in 1229.[30]

Among his first actions, Ögedei sent troops to subjugate the Bashkirs, Bulgars, and other nations in the Kipchak-controlled steppes.[31] In the east, Ögedei's armies re-established Mongol authority in Manchuria, crushing the Eastern Xia regime and Water Tatars. In 1230, the Great Khan personally led his army in the campaign against the Jin Dynasty (China). Ögedei's general Subutai captured Emperor Wanyan Shouxu's capital, Kaifeng in 1232.[32] In 1234, three armies commanded by Ögedei's sons Kochu and Koten, as well as the Tangut general Chagan, invaded southern China. With the assistance of the Song Dynasty, the Mongols finished off the Jin in 1234.[33][34] In the West, Ögedei's general Chormaqan destroyed Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu, the last shah of the Khwarizmian Empire. The small kingdoms in Southern Persia voluntarily accepted Mongol supremacy.[35][36] In East Asia, there were a number of Mongolian campaigns into Goryeo Korea, but Ögedei's attempt to annex the Korean Peninsula met with little success. The king of Goryeo, Gojong, surrendered but revolted and massacred Mongol darughachis (overseers), and then moved his imperial court from Gaeseong to Ganghwa Island.[37]

As the empire grew, Ögedei established a Mongol capital at Karakorum in northwestern Mongolia.[38]

Meanwhile, in an offensive action against the Song Dynasty, Mongol armies captured Siyang-yang, the Yangtze and Sichuan, but did not secure their control over the conquered sites. The Song generals were able to recapture Siyang-yang from the Mongols in 1239. After the sudden death of Ögedei's son Kochu in Chinese territory, the Mongols withdrew from southern China, although Kochu's brother Prince Koten invaded Tibet right after their withdrawal.[23]

Another grandson of Genghis Khan, Batu Khan, overran the countries of the Bulgars, the Alans, the Kypchaks, Bashkirs, Mordvins, Chuvash, and other nations of the southern Russian steppe. By 1237, the Mongols began encroaching upon their first Russian principality, Ryazan. After a 3 day-siege using heavy attacks, the Mongols captured the city and massacred its inhabitants, then proceeded to destroy the army of the Grand principality of Vladimir at the Sit River. The Mongols captured the Alania capital, Maghas, in 1238. By 1240, all Rus’ lands including Kiev had fallen to the Asian invaders except for a few northern cities. Mongol troops under Chormaqan in Persia connected his invasion of Transcaucasia with the invasion of Batu and Subutai, forced the Georgian and Armenian nobles to surrender as well.[39]

Despite the military successes, strife continued within the Mongol ranks. Batu's relations with Güyük, Ögedei's eldest son, and Büri, the beloved grandson of Chagatai Khan, remained tense, and worsened during Batu's victory banquet in southern Russia, nevertheless Güyük and Buri couldn´t do anything to harm Batu's position as long as his uncle Ögedei was still alive. Meanwhile, Ögedei continued with Mongol invasions into the Indian subcontinent, temporarily investing Uchch, Lahore and Multan of the Delhi Sultanate and stationing a Mongol overseer in Kashmir,[40] though the invasions into India eventually failed and were forced to drive back. In northeastern Asia, Ögedei agreed to settle conflicts with Goryeo by making it a client state and sent Mongolian princesses to wed Goryeo princes. He then reinforced his keshig with the Koreans through both diplomacy and military force.[41][42][43]

The advance into Europe continued with Mongol invasions of Poland, Hungary and Transylvania. When the western flank of the Mongols plundered Polish cities, a European alliance between the Poles, the Moravians, and the Christian military orders of the Hospitallers, Teutonic Knights and the Templars assembled sufficient forces to halt, although briefly, the Mongol advance at Legnica. The Hungarian army, their Croatian allies and the Templar Knights were beaten by Mongols at the banks of Sajo River on April 11, 1241. After their victories over European Knights at Legnica and Muhi, Mongol armies quickly advanced across Bohemia, Serbia, Babenberg Austria and into the Holy Roman Empire,[44][45] but before Batu's forces could continue into Vienna and northern Albania, news of Ögedei's death in December 1241 brought a halt to the invasion.[46][47] As was customary in Mongol military tradition, all princes of Genghis's line had to attend the kurultai to elect a successor. Batu and his western Mongol army withdrew from Central Europe the next year.[48]

Post-Ögedei power struggles

Following the Great Khan Ögedei's death in 1241, and before the next kurultai, Ögedei's widow Töregene took over the empire. She persecuted her husband's Khitan and Muslim officials, giving high positions to her own allies instead. She built palaces, cathedrals and social structures on an imperial scale, supporting religion and education. She was able to win over most Mongol aristocrats to support Ögedei's son Güyük. But Batu, ruler of the Golden Horde, refused to come to the kurultai, claiming he was ill and the Mongolian climate was too harsh for him. The resulting stalemate lasted more than four years, and further destabilized the unity of the empire.[49]

When Genghis Khan's youngest brother Temüge threatened Töregene to seize the throne, Güyük came to Karakorum to try and secure his position.[50] Batu eventually agreed to send his brothers and generals to the kurultai which Töregene convened in 1246. Güyük by this time was ill and alcoholic, but his campaigns in Manchuria and Europe gave him the kind of stature necessary for a Great Khan. He was duly elected at a ceremony attended by Mongols and foreign dignitaries from both within and without the empire—leaders of vassal nations, and representatives from Rome and other entities, who came to the kurultai to show their respects and negotiate diplomacy.[51][52]

Güyük took steps to reduce corruption, announcing that he would continue the policies of his father Ögedei, not Töregene. He punished Töregene's supporters, except governor Arghun the Elder. He also replaced young Qara Hülëgü, the khan of the Chagatai Khanate, with his favorite cousin Yesü Möngke to assert his newly conferred powers. He restored his father's officials to their former positions and was surrounded by the Uyghur, Naiman and Central Asian officials, favoring Han Chinese commanders who helped his father's conquest of Northern China. He continued military operations in Korea, advanced into Song China in the south and Iraq in the west, and ordered an empire-wide census. Güyük also divided the Sultanate of Rum between Izz-ad-Din Kaykawus and Rukn ad-Din Kilij Arslan, though Kaykawus disagreed with this decision.[53]

Not all parts of the empire respected Güyük's election. The Hashshashins, former Mongol allies whose Grand Master Hasan Jalalud-Din had offered his submission to Genghis Khan in 1221, angered Güyük by refusing to submit, instead murdering Mongol generals in Persia. Güyük appointed his best friend's father Eljigidei as chief commander of the troops in Persia, and gave them the task of both reducing the strongholds of the Assassins a Muslim mouvement, and conquering the Abbasids in the center of the Islamic world, Iran and Iraq.[53][54][55]

In 1248, Güyük raised more troops and suddenly marched westwards from the Mongol capital of Karakorum. The reasoning was unclear: some sources wrote that he sought to recuperate his personal property Emyl; others suggested that he might have been moving to join Eljigidei to conduct a full-scale conquest of the Middle East, or possibly to make a surprise attack on his rival cousin Batu Khan in Russia. Suspicious of Güyük's motives, Sorghaghtani Beki, the widow of Genghis's son Tolui, secretly warned her nephew Batu of Güyük's approach. Batu had himself been traveling eastwards at the time, possibly to pay homage, or perhaps with other plans in mind. Before the forces of Batu and Güyük met though, Güyük, sick and worn out by travel, died en route at Qum-Senggir in Eastern Turkestan, possibly a victim of poison.[56]

Güyük's widow Oghul Qaimish stepped forward to take control of the empire, but she lacked the skills of her mother-in-law Töregene, and her young sons Khoja and Naku and other princes challenged her authority. To decide on a new Great Khan, Batu called a kurultai on his own territory in 1250. As it was far from the Mongolian heartland, members of the Ögedeid and Chagataid families refused to attend. The kurultai offered the throne to Batu, but he rejected it, claiming he had no interest in the position. He instead nominated Möngke, a grandson of Genghis of his son Tolui lineage. Möngke was leading a Mongol army in Russia, Northern Caucasus and Hungary. The pro-Tolui faction rose up and supported Batu's choice, and Möngke was elected, though given the kurultai's limited attendance and location, it was of questionable validity. Batu sent Möngke under the protection of his brothers, Berke and Tukhtemur, and his son Sartaq to assemble a more formal kurultai at Kodoe Aral in the heartland. The supporters of Möngke invited Oghul Qaimish and other main Ögedeid and Chagataid princes to attend the kurultai, but they refused each time. The Ögedeid and Chagataid princes refused to accept a descendant of Genghis's son Tolui as leader, demanding that only descendants of Genghis's son Ögedei could be Great Khan.[57]

Toluid reformation

When Möngke's mother Sorghaghtani and their cousin Berke organized a second kurultai on July 1, 1251, the assembled throng proclaimed Möngke Great Khan of the Mongol Empire. This marked a major shift in the leadership of the empire, transferring power from the descendants of Genghis's son Ögedei to the descendants of Genghis's son Tolui. The decision was acknowledged by a few of the Ögedeid and Chagataid princes, such as Möngke's cousin Kadan and the deposed khan Qara Hülëgü, but one of the other legitimate heirs, Ögedei's grandson Shiremun, sought to topple Möngke. Shiremun moved with his own forces towards the emperor's nomadic palace with a plan for an armed attack, but Möngke was alerted by his falconer of the plan. Möngke ordered an investigation of the plot, which led to a series of major trials all across the empire. Many members of the Mongol elite were found guilty and put to death, with estimates ranging from 77–300, though princes of Genghis's royal line were often exiled rather than executed. Möngke eliminated the Ögedeid and the Chagatai families' estates and shared the western part of the empire with his ally Batu Khan. After the bloody purge, Möngke ordered a general amnesty for prisoners and captives, but ever after, the power of the Great Khan's throne remained firmly with the descendants of Genghis's son Tolui.[58]

Möngke was a serious man who followed the laws of his ancestors and avoided alcoholism. He was tolerant of outside religions and artistic styles, which led to the building of foreign merchants' quarters, Buddhist monasteries, mosques, and Christian churches in the Mongol capital. As construction projects continued, Karakorum was adorned with Chinese, European and Persian architecture. One famous example was a large silver tree with cleverly designed pipes which dispensed various drinks. The tree, topped by a triumphant angel, was crafted by Guillaume Boucher, a Parisian goldsmith.[59]

Although he had a strong Chinese contingent, Möngke relied heavily on Muslim and Mongol administrators, and launched a series of economic reforms to make government expenses more predictable. His court limited government spending and prohibited nobles and troops from abusing civilians or issuing edicts without authorization. He commuted the contribution system into a fixed poll tax which was collected by imperial agents and forwarded to units in need. His court also tried to lighten the tax burden on commoners by reducing tax rates. Along with the reform of the tax system, he reinforced the guards at the postal relays and centralized control of monetary affairs. Möngke also ordered an empire-wide census in 1252 which took several years to complete, not being finished until Novgorod in the far northwest was counted in 1258.[60]

In another move to consolidate his power, Möngke assigned his brothers Hulagu and Kublai to rule Persia and Mongol-held China. In the southern part of the empire, he continued his predecessors' struggle against the Song Dynasty. In order to outflank the Song from three directions, Möngke dispatched Mongol armies under his brother Kublai to Yunnan, and under his uncle Iyeku to subdue Korea and pressure the Song from that direction as well. Kublai conquered the Dali Kingdom in 1253, and Möngke's general Qoridai stabilized his control over Tibet, inducing leading monasteries to submit to Mongol rule. Subutai's son, Uryankhadai, reduced neighboring peoples of Yunnan to submission and beat the Trần Dynasty in northern Vietnam into temporary submission in 1258.[53]

After stabilizing the empire's finances, Möngke once again sought to expand its borders. At kurultais in Karakorum in 1253 and 1258 he approved new invasions of the Middle East and south China. Möngke put Hulagu in overall charge of military and civil affairs in Persia, and appointed Chagataids and Jochids to join Hulagu's army. The Muslims from Qazvin denounced the menace of the Nizari Ismailis, a heretical sect of Shiites. The Mongol Naiman commander Kitbuqa began to assault several Ismaili fortresses in 1253, before Hulagu deliberately advanced in 1256. Ismaili Grand Master Rukn ud-Din surrendered in 1257 and was executed. All of the Ismaili strongholds in Persia were destroyed by Hulagu's army in 1257 though Girdukh held out until 1271.[61]

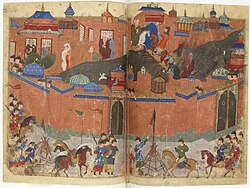

The center of the Islamic Empire at the time was Baghdad, which had held power for 500 years but was suffering internal divisions. When its caliph al-Mustasim refused to submit to the Mongols, Baghdad was besieged and captured by the Mongols in 1258, an event considered as one of the most catastrophic events in the history of Islam, and sometimes compared to the rupture of the Kaaba. With the destruction of the Abbasid Caliphate, Hulagu had an open route to Syria and moved against the other Muslim powers in the region. His army advanced towards Ayyubid-ruled Syria, capturing small local states en route. The sultan Al-Nasir Yusuf of the Ayyubids refused to show himself before Hulagu; however, he had accepted Mongol supremacy two decades earlier. When Hulagu headed further west, the Armenians from Cilicia, the Seljuks from Rum and the Christian realms of Antioch and Tripoli submitted to Mongol authority, joining the Mongols in their assault against the Muslims. While some cities surrendered without resisting, others such as Mayafarriqin fought back; their populations were massacred and the cities were sacked.[62]

Meanwhile, in the northwestern portion of the empire, Batu's successor and younger brother Berke sent punitive expeditions to Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and Poland. Dissension began brewing between the northwestern and southwestern sections of the Mongol Empire, as Batu suspected that Hulagu's invasion of Western Asia would result in the elimination of Batu's own predominance there.[63]

Disintegration

Dispute over succession

In the southern part of the empire, Möngke Khan himself led his army to complete the conquest of China. Military operations were generally successful, but prolonged, so the forces did not withdraw to the north as was customary when the weather turned hot. Disease ravaged the Mongol forces with bloody epidemics, and Möngke died there on August 11, 1259. This event began a new chapter of history for the Mongols, as again a decision needed to be made on a new Great Khan. Mongol armies across the empire withdrew from their campaigns to once again convene for a new kurultai.[64]

Möngke's brother Hulagu broke off his successful military advance into Syria, withdrawing the bulk of his forces to Mughan and leaving only a small contingent under his general Kitbuqa. The opposing forces in the region, the Christian Crusaders and Muslim Mamluks, both recognizing that the Mongols were the greater threat, took advantage of the weakened state of the Mongol army and engaged in an unusual passive truce with each other. In 1260, the Mamluks advanced from Egypt, being allowed to camp and resupply near the Christian stronghold of Acre, and engaged Kitbuqa's forces just north of Galilee, at the Battle of Ain Jalut. The Mongols were defeated, and Kitbuqa executed. This pivotal battle marked the western limit for Mongol expansion, as the Mongols were never again able to make any serious military advances farther than Syria.[65]

In a separate part of the empire, another brother of Hulagu and Möngke, Kublai, heard of the Great Khan's death at the Huai in China. Rather than returning to the capital though, he continued his advance into the Wuchang area of China, near the Yangtze River. Their younger brother Ariqboke took advantage of the absence of Hulagu and Kublai, and used his position at the capital to win the title of Great Khan for himself, with representatives of all the family branches proclaimed him as the leader at the kurultai in Karakorum. When Kublai learned of this, he summoned his own kurultai at Kaiping, where virtually all the senior princes and great noyans resident in North China and Manchuria supported his own candidacy over that of Ariqboke.[48]

Civil war

Battles ensued between the armies of Kublai and those of his brother Ariqboke, which included forces still loyal to Möngke's previous administration. Kublai's army easily eliminated Ariqboke's supporters, and seized control of the civil administration in southern Mongolia. Further challenges took place from their cousins, the Chagataids. Kublai sent Abishka, a Chagataid prince loyal to him, to take charge of Chagatai's realm. But Ariqboke captured and then executed Abishka, having his own man Alghu crowned there instead. Kublai's new administration blockaded Ariqboke in Mongolia to cut off food supplies, causing a famine. Karakorum fell quickly to Kublai, but Ariqboke rallied and re-took the capital in 1261.[66][67][68]

In the southwestern Ilkhanate, Hulagu was loyal to his brother Kublai, but clashes with their cousin Berke, the ruler of the Golden Horde in the northwestern part of the empire, began in 1262. The suspicious deaths of Jochid princes in Hulagu's service, unequal distribution of war booties and Hulagu's massacres of the Muslims increased the anger of Berke, who considered supporting a rebellion of the Georgian Kingdom against Hulagu's rule in 1259–1260.[69][full citation needed] Berke also forged an alliance with the Egyptian Mamluks against Hulagu, and supported Kublai's rival claimant, Ariqboke.[70] Hulagu died on February 8, 1264. Berke sought to take advantage of this and invade Hulagu's realm, but died himself along the way, and a few months later, Alghu Khan of the Chagatai Khanate died as well. Kublai named Hulagu's son Abaqa as a new Ilkhan, and Abaqa sought foreign alliances, such as attempting to form a Franco-Mongol alliance with the Europeans against the Egyptian Mamluks. To lead the Golden Horde, Kublai nominated Batu's grandson Möngke Temür.[71] Ariqboqe surrendered to Kublai at Shangdu on August 21, 1264.[72]

In the south, after the fall of Xiangyang in 1273, the Mongols sought the final conquest of the Song Dynasty in South China. In 1271, Kublai renamed the new Mongol regime in China as the Yuan Dynasty, and sought to sinicize his image as Emperor of China in order to win the control of the millions of Chinese. Kublai moved his headquarters to Dadu, the genesis for what later became the modern city of Beijing, although his establishment of a capital there was a controversial move to many Mongols who accused him of being too closely tied to Chinese culture.[73][74] But the Mongols were eventually successful in their campaigns against China, and the Chinese Song imperial family surrendered to the Yuan in 1276, making the Mongols the first non-Chinese people to conquer all of China. Kublai used his base to build a powerful empire, creating an academy, offices, trade ports and canals, and sponsoring arts and science. Mongol records list 20,166 public schools created during his reign.[75]

Having achieved actual or nominal dominion over much of Eurasia, and having seen his successful conquest of China, Kublai was in a position to look beyond China. However, his costly invasions of Burma, Annam, Sakhalin and Champa secured only the vassal status of those countries. Mongol invasions of Japan (1274 and 1280) and Java (1293) failed.[75]

Nogai and Konchi, the khan of the White Horde, established friendly relations with the Yuan Dynasty and the Ilkhanate. Political disagreement between contending branches of the family over the office of Great Khan continued, but the economic and commercial success of the Mongol Empire continued despite the squabbling.[76][77][78]

Political struggles

Major changes occurred in the Mongol Empire in the late 1200s. Kublai Khan, after having conquered all of China and established the Yuan Dynasty, died in 1294, and was succeeded by his grandson Temür Khan, who continued Kublai's policies. The Ilkhanate remained loyal to the Yuan court but endured its own power struggle, in part because of a dispute with the growing Islamic factions within the southwestern part of the empire. When Ghazan took the throne of the Ilkhanate in 1295, he formally accepted Islam as his own religion, marking a turning point in Mongol history after which Mongol Persia became more and more Islamic. Despite this though, Ghazan continued to strengthen ties with Temür Khan and the Yuan Dynasty in the east. It was politically useful to advertise the Great Khan's authority in the Ilkhanate, because the Golden Horde in Russia had long made claims on nearby Georgia.[79] Within four years, Ghazan began sending tributes to the Yuan court, appealed to other khans to accept Temür Khan as their overlord, and oversaw an extensive program of cultural and scientific interaction between the Ilkhanate and the Yuan Dynasty in the following decades.[80]

Ghazan's faith may have been Islamic, but he continued his ancestors’ war with the Egyptian Mamluks, and consulted with his old Mongolian advisers in his native tongue. He defeated the Mamluk army at the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar in 1299, but was only briefly able to occupy Syria, due to distracting raids from the Chagatai Khanate, under its de facto ruler Kaidu, who was at war with both the Ilkhans and the Yuan Dynasty.[citation needed] Struggling for influence within the Golden Horde, Kaidu sponsored his own candidate Kobeleg against Bayan (r. 1299–1304), the khan of the White Horde. Bayan, after receiving military support from the Mongols in Russia, requested assistance from both the Great Khan Temür and the Ilkhanate to organize a unified attack against Kaidu's forces. Temür was amenable, and enlarged counterattacks against Kaidu a year later. After a bloody battle with Temür's armies near Zawkhan River in 1301, the old valiant Kaidu died, and was succeeded by Duwa.[81][82]

In spite of his conflicts with Kaidu and Duwa, Yuan emperor Temür established a tributary relationship with the war-like Shan brothers after his series of military operations against Thailand from 1297 to 1303. This was to mark the end of the southern expansion of the Mongols. Some Mongols sought to decrease internal strife, and unify under Temür. Duwa initiated a peace proposal and persuaded the Ögedeids that "Let we Mongols stop shedding blood of each other. It is better to surrender to Khagan Temür".[84][85] In 1304, all khanates approved a peace treaty, and accepted Temür's supremacy.[86][87][88][89]

Duwa was challenged by Kaidu's son Chapar, but with the assistance of Temür, Duwa defeated the Ögedeids. Tokhta of the Golden Horde, also seeking a general peace, sent 20,000 men to buttress the Yuan frontier.[90] After Tokhta's death in 1312 though, he was succeeded by Ozbeg (r. 1313–41), who seized the throne of the Golden Horde and persecuted non-Muslim Mongols. The Yuan's influence on the Horde was largely reversed and border clashes between Mongol states resumed. Ayurbawda Khan's envoys backed Tokhta's son against Ozbeg.[citation needed]

In the Chagatai Khanate, Esen Buqa I (r. 1309-1318) was enthroned as khan after suppressing a sudden rebellion by Ögedei's descendants and driving Chapar into exile. The Yuan and Ilkhanid armies eventually attacked the Chagatai Khanate.

Realizing economic benefits and the Genghisid legacy, Ozbeg reopened friendly relations with the Yuan in 1326, and strengthened ties with the Muslim world as well, building mosques and other elaborate places such as baths.[citation needed]

By the second decade of the 14th century, Mongol invasions had further decreased. In 1323, Abu Said Khan (r. 1316-35) of the Ilkhanate signed a peace treaty with Egypt. At his request, the Yuan court awarded his custodian Chupan the title of commander-in-chief of all Mongol khanates. But Chupan's reputation could not save his life in 1327.[91] A new civil war erupted in the Yuan Dynasty in 1327-1328, with Chagatai khan Eljigidey (r. 1326–29) supporting Kusala, the Yuan Khagan Khayisan's son, as Great Khan. Kusala was elected on August 30, 1329. Fearing Chagataid influence on the Yuan, Tugh Temür's (1304–1332) Kypchak commander poisoned him, and took power for himself. In order to be accepted by other khanates as the sovereign of Mongol world, Tugh Temür, who had a good knowledge of Chinese language and history and was also a creditable poet, calligrapher, and painter, sent Genghisid princes and descendants of other notable Mongol generals to the Chagatai Khanate, Ilkhan Abu Said and Ozbeg. In response to the emissaries, they all agreed to send tribute each year.[92] Tugh Temür also gave lavish presents and an imperial seal to Eljigidey to mollify his anger. The Kypchak and the Alans became even more powerful at the court of the Yuan than had been seen since Temür's reign. Pope John XXII was presented a memorandum from the eastern church describing their Pax Mongolica: "...Khagan is one of the greatest monarchs and all lords of the state, e.g. the king of Almaligh (Chagatai Khanate), emperor Abu Said and Uzbek Khan, are his subjects, saluting his holiness to pay their respects. These 3 monarchs send their overlord leopards, camels, falcons as well as precious jewelries every year. ... They acknowledge him as their absolute supreme lord.".[93]

With the relative stability (Pax Mongolica) brought to the region by the Mongol conquests, international trade and cultural exchanges flourished between Asia and Europe. The communications between the Yuan Dynasty in China and Ilkhanate in Persia further encouraged the trade and commerce between the east and the west. Patterns of Yuan royal textiles could be found on the opposite side of the empire adorning Armenian decorations; trees and vegetables were transplanted across the empire; and technological innovations spread from Mongol dominions towards the West.[94][citation needed]

Fall

With the death of Ilkhan Abu Said Bahatur in 1335, the Mongol rule in Persia fell into political anarchy. A year later his successor was killed by an Oirat governor and the Ilkhanate was divided between the Suldus, the Jalayir, Qasarid Togha Temür (d. 1353) and Persian warlords. Taking advantage of the chaos, the Georgians pushed the Mongols out of their own territory, and the Uyghur commander Eretna established an independent state (Ertenids) in Anatolia in 1336. Following the downfall of their Mongol masters, the all-time loyal vassal, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, received escalating threats from the Mamluks, and were eventually overrun.[citation needed]

Along with the dissolution of the Mongol Ilkhanate in Persia, Mongol rulers in China and the Chagatai Khanate were also in turmoil. Plagues such as the Black Death, which certainly started in the Mongol dominions and then spread to Europe, added to the confusion. Disease devastated all the khanates, cutting off commercial ties and killing off millions.[95] By the end of the 14th century, it may have taken 70–100 million lives in Africa, Asia and Europe.[citation needed]

As the power of the Mongols declined, chaos erupted everywhere as non-Mongol leaders struggled for their own influence. The Golden Horde lost all of its western dominions (including modern Belarus and Ukraine) to Poland and Lithuania from 1342 to 1369. Muslim and non-Muslim princes in the Chagatai Khanate warred with each other from 1331–1343, and the Chagatai Khanate disintegrated when non-Genghisid warlords set up their own puppet khans in Transoxiana and Moghulistan. Janibeg Khan (r. 1342–1357) briefly reasserted Jochid dominance over the Chaghataids to restore their former glory. Demanding submission from an offshoot of the Ilkhanate in Azerbaijan, he boasted that "today three uluses are under my control". However, rival families of the Jochids began fighting for the throne of the Golden Horde after the assassination of his successor Berdibek Khan in 1359. The last Yuan ruler Toghan Temür (r. 1333–70) was powerless to regulate those troubles because the empire had nearly reached its end. His court's unbacked currency had entered a hyperinflationary spiral and the Han-Chinese people revolted due to the Yuan's harsh restrictions. In the 1350s Gongmin of Goryeo successfully pushed Mongolian garrisons back and exterminated the family of Toghan Temür Khan's empress while Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen managed to eliminate the Mongol influence in Tibet.[96]

Increasingly isolated from their subjects, the Mongols quickly lost most of China to the rebellious Ming forces in 1368 and fled to their homeland Mongolia. After the overthrow of the Yuan Dynasty, the Golden Horde lost touch with Mongolia and China, while the two main parts of the Chagatai Khanate were defeated by Timur (Tamerlane) (1336–1405). The Golden Horde broke into smaller Turkic-hordes that declined steadily in power through four long centuries. Among them, the khanate's shadow Great Horde survived until 1502, when one of its successors, the Crimean Khanate, sacked Sarai. The Yuan remnants, known as Northern Yuan, continued to rule Mongolia until 1635 when the semi-nomadic Manchus from Manchuria defeated them. The Khalkha under the Genghisids and their former subjects, the Oirat Mongols, lost their independence to the Qing Dynasty in 1691 and 1755 respectively, and the remnants of the Crimean Khanate were annexed by the Russian Empire in 1783.[97]

Military setup

The number of troops mustered by the Mongols is the subject of some scholarly debate,[98] but was at least 105,000 in 1206.[99] The Mongol military organization was simple but effective, based on the decimal system. The army was built up from squads of ten men each, called an arbat; ten arbats constituted a company of one hundred, called a zuut; ten zuuts made a regiment of one thousand called myanghan and ten myanghans would then constitute a division of ten thousand (tumen). The Mongols were most famous for their horse archers, but troops armed with lances were equally skilled, and the Mongols recruited other military talents from the cities they conquered. With experienced Chinese engineers and bombardier corps who were experts in building trebuchets, Xuanfeng catapults and other machines, the Mongols could lay siege to fortified positions, sometimes building machinery on the spot using available local resources.[100]

Forces under the command of the Mongol Empire were trained, organized, and equipped for mobility and speed. Mongol soldiers were more lightly armored than many of the armies they faced, but able to make up for it with maneuverability. Each Mongol warrior would usually travel with multiple horses, allowing him to quickly switch to a fresh mount as needed. In addition, soldiers of the Mongol army functioned independently of supply lines, considerably speeding up army movement. Skillful use of couriers enabled these armies to maintain contact with each other and their leadership. Discipline was inculcated during a nerge (traditional hunt), as reported by Juvayni. These hunts were distinctive from hunts in other cultures where they were the equivalent to small unit actions. Mongol forces would spread out in a line, surround an entire region, and then drive all of the game within that area together. The goal was to let none of the animals escape and slaughter them all.[101]

Another advantage of the Mongols was their ability to traverse large distances even in unusual cold winters; for instance, frozen rivers led them like highways to large urban centers on their banks. In addition to siege engineering, the Mongols were also adept at river-work, crossing the river Sajó in spring flood conditions with thirty thousand cavalry soldiers in a single night during the battle of Mohi (April, 1241) to defeat the Hungarian king Béla IV. Similarly, in the attack against the Muslim Khwarezmshah, a flotilla of barges was used to prevent escape on the river.[citation needed]

Traditionally known for their prowess with ground forces, the Mongols rarely used naval power, with a few exceptions. In the 1260s and 1270s they used seapower while conquering the Song Dynasty of China, though they were unable to mount successful seaborne campaigns against Japan. Around the Eastern Mediterranean, their campaigns were almost exclusively land-based, with the seas being controlled by the Crusader and Mamluk forces.[102]

All military campaigns were preceded by careful planning, reconnaissance and gathering of sensitive information relating to enemy territories and forces. The success, organization and mobility of the Mongol armies permitted them to fight on several fronts at once. All adult males up to the age of 60 were eligible for conscription into the army, a source of honor in their tribal warrior tradition.[103]

Society

Law and governance

The Mongol Empire was governed by a code of law devised by Genghis, called Yassa, meaning "order" or "decree". A particular canon of this code was that those of rank shared much of the same hardship as the common man. It also imposed severe penalties – e.g., the death penalty was decreed if one mounted soldier following another did not pick up something dropped from the mount in front. Penalties were also decreed for rape and to some extent for murder. On the whole, the tight discipline made the Mongol Empire extremely safe and well-run; European travelers were amazed by the organization and strict discipline of the people within the Mongol Empire.[citation needed]

Under Yassa, chiefs and generals were selected based on merit. Religious tolerance was guaranteed, and thievery and vandalizing of civilian property was strictly forbidden.[citation needed]

The empire was governed by a non-democratic parliamentary-style central assembly, called Kurultai, in which the Mongol chiefs met with the Great Khan to discuss domestic and foreign policies. Kurultais were also convened for the selection of each new Great Khan.[citation needed]

Genghis was very tolerant of other religions, and never persecuted people on religious grounds. This was associated with their culture and progressive thought (Roger Bacon). Some historian of the 20th century thought that it was a good military strategy, the occasion in which he was at war with Sultan Muhammad of Khwarezm, other Islamic leaders did not join the fight against Genghis — it was instead seen as a non-holy war between two individuals.[citation needed]

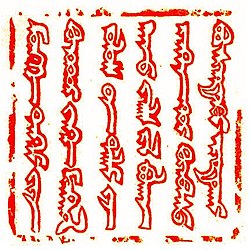

Throughout the empire, trade routes and an extensive postal system (yam) were created. Many merchants, messengers and travelers from China, the Middle East and Europe used the system. Genghis Khan also created a national seal, encouraged the use of a written alphabet in Mongolia, and exempted teachers, lawyers, and artists from taxes, although taxes were heavy on all other subjects of the empire.[citation needed]

At the same time, any resistance to Mongol rule was met with massive collective punishment. Cities were destroyed and their inhabitants slaughtered if they defied Mongol orders.[citation needed]

Religions

Mongols were highly tolerant of most religions, to the extent of sponsoring several at the same time. At the time of Genghis Khan, virtually every religion had found converts, from Buddhism to Christianity and Manichaeism to Islam. To avoid strife, Genghis Khan set up an institution that ensured complete religious freedom, though he himself was a shamanist. Under his administration, all religious leaders were exempt from taxation, and from public service.[104]

Initially there were few formal places of worship, because of the nomadic lifestyle. However, under Ögedei (1186–1241), several building projects were undertaken in the Mongol capital of Karakorum. Along with palaces, Ögedei built houses of worship for the Buddhist, Muslim, Christian, and Taoist followers. The dominant religions at that time were Shamanism, Tengrism and Buddhism, although Ögedei's wife was a Nestorian Christian.[105] Eventually, three of the four principal khanates embraced Islam.[106][107]

Arts and literature

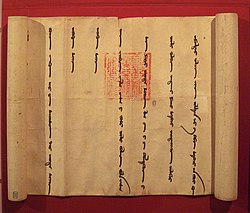

The oldest surviving literary work in the Mongolian language is The Secret History of the Mongols, which was written for the royal family sometime after Genghis Khan's death in 1227. It is the most significant native account of Genghis's life and genealogy, covering his origins and childhood, through to the establishment of the Mongol Empire and the reign of his son, Ögedei. Another classic from the empire is the Jami' al-tawarikh, or "Universal History". It was commissioned in the early 14th century by the Ilkhan Abaqa Khan, as a way of documenting the entire world's history, to help establish the Mongols' own cultural legacy. With hundreds of illustrated pages, it was effectively one of the first written histories of the world.

The Mongols also appreciated the visual arts, though their taste in portraiture was strictly focused on portraits of their horses, rather than of people.

Mail system

The Mongol Empire had an ingenious and efficient mail system for the time, often referred to by scholars as the Yam, which had lavishly furnished and well guarded relay posts known as örtöö setup all over the Mongol Empire. The yam system would be replicated later in the United States, in the form of the Pony Express.[108] A messenger would typically travel 25 miles (40 km) from one station to the next, either receiving a fresh, rested horse, or relaying the mail to the next rider to ensure the speediest possible delivery. The Mongol riders regularly covered 125 miles (200 km) per day, better than the fastest record set by the Pony Express some 600 years later.[citation needed]

Genghis and his successor Ögedei built a wide system of roadways, one of which carved the Altai Range. After his enthronement, Ögedei further organized the road system, ordering the Chagatai Khanate and Golden Horde to link up roads in western parts of the Mongol Empire.[109][citation needed] In order to reduce pressure on households, he set up relay stations with attached households every 25 miles (40 km). Anyone with paiza was allowed to stop there for re-mounts and specified rations, while those carrying military identities used the Yam even without a paiza. When the Great Khan died in Karakorum, news reached the Mongol forces under Batu Khan in Central Europe within 4–6 weeks thanks to the Yam.[46]

Kublai Khan, the founder of the Yuan Dynasty, built special relays for high officials, as well as ordinary relays which had hostels. During Kublai's reign, the Yuan communication system consisted of some 1,400 postal stations, which used 50,000 horses, 8,400 oxen, 6,700 mules, 4,000 carts, and 6,000 boats.[citation needed] In Manchuria and southern Siberia, the Mongols still used dogsled relays for the yam. In the Ilkhanate, Ghazan restored the declining relay system in the Middle East on a restricted scale. He constructed some hostels and decreed that only imperial envoys could receive a stipend. The Jochids of the Golden Horde financed their relay system by a special yam tax.[citation needed]and was gay

Silk Road

The Mongols had a strong history of supporting merchants and trade. Genghis Khan had encouraged foreign merchants early in his career, even before uniting the Mongols. Merchants provided him with information about neighboring cultures, served as diplomats and official traders for the Mongols, and were essential for many needed goods, since the Mongols produced little of their own. Mongols sometimes provided capital for merchants and sent them far afield, in an ortoq (merchant partner) arrangement. As the empire grew, any merchants or ambassadors with proper documentation and authorization received protection and sanctuary as they traveled through Mongol realms. Well-traveled and relatively well-maintained roads linked lands from the Mediterranean basin to China, greatly increasing overland trade and resulting in some dramatic stories of those who travelled through what would come be known as the famed Silk Road. Marco Polo is a famous western explorer who traveled east along the Silk Road, and the Chinese Mongol monk Rabban Bar Sauma made a comparably epic journey along the Road who ventured from his home of Khanbaliq (Beijing) to as far as Europe. And European missionaries, like William of Rubruck, also traveled to the Mongol court to convert believers to their cause, or went as papal envoys (sent on behalf of the pope) to correspond with Mongol rulers in an attempt to secure a Franco-Mongol alliance. It was rare, however, for anyone to journey the full length of Silk Road. Instead, merchants moved products like a bucket brigade, goods being traded from one middleman to another, moving from China all the way to the West; the goods moved over such long distances reached extravagant prices.[citation needed]

After Genghis, the merchant partner business continued to flourish under his successors Ögedei and Güyük. Merchants brought clothing, food, information, and other provisions to the imperial palaces, and in return the Great Khans gave the merchants tax exemptions, and allowed them to use the official relay stations of the Mongol Empire. Merchants also served as tax farmers in China, Russia and Iran. If the merchants were attacked by bandits, losses were made up from the imperial treasury.[citation needed]

Policies changed under the Great Khan Möngke. Because of money laundering and overtaxing, he attempted to limit abuses and sent imperial investigators to supervise the ortoq businesses. He decreed all merchants must pay commercial and property taxes, and he paid off all drafts drawn by high ranking Mongol elites from the merchants. This policy continued in the Yuan Dynasty.[citation needed]

The fall of the Mongol Empire in the 14th century led to the collapse of the political, cultural, and economic unity along the Silk Road. Turkic tribes seized the western end of the Silk Road trade routes from the decaying Byzantine Empire, and sowed the seeds of a Turkic culture that would later crystallize into the Ottoman Empire under the Sunni faith. In the East, the native Chinese overthrew the Yuan Dynasty in 1368, launching their own Ming Dynasty and pursuing a policy of economic isolationism.[110]

Legacy

The Mongol Empire had a lasting impact, unifying large regions, some of which (such as eastern and western Russia and the western parts of China) remain unified today, albeit under different rulership. The Mongols, except the main population, might have been assimilated into local populations after the fall of the empire, and some of these descendants adopted local religions — for example, the eastern khanates largely adopted Buddhism, and the western khanates adopted Islam, largely under Sufi influence.[111]

According to some[specify] interpretations, Genghis Khan's conquests caused wholesale destruction on an unprecedented scale in certain geographical regions, and therefore led to some changes in the demographics of Asia, such as the mass migration of the Iranian tribes of Central Asia into modern-day Iran. The Islamic world was also subject to massive changes as a result of Mongol invasions. The population of the Iranian plateau suffered from widespread disease and famine, resulting in the deaths of up to three-quarters of its population, possibly 10 to 15 million people. Historian Steven Ward estimates that Iran's population did not again reach its pre-Mongol levels until the mid-20th century.[112]

Non-military achievements of the Mongol Empire included the introduction of a writing system, a Mongol alphabet based on the Uighur characters, that is still used today in Inner Mongolia.[113]

Some of the other long-term consequences of the Mongol Empire include:

- Moscow rose to prominence during the Mongol-Tatar yoke, some time after Russian rulers were accorded the status of tax collectors for the Mongols. The fact that the Russians collected tribute and taxes for the Mongols meant that the Mongols themselves would rarely visit the lands that they owned. The Russians eventually gained military power, and their ruler Ivan III overthrew the Mongols completely to form the Russian Tsardom. After the Great stand on the Ugra river proved the Mongols vulnerable, this led to the independence of the Grand Duke of Moscow.[citation needed]

- Europe's knowledge of the known world was immensely expanded by the information brought back by ambassadors and merchants. When Columbus sailed in 1492, his missions were to reach Cathay, the land of the Grand Khan in China, and give him a letter from the monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile.[citation needed]

- Some research studies indicate that the Black Death which devastated Europe in the late 1340s may have traveled from China to Europe along the trade routes of the Mongol Empire. In 1347, the Genoese possessor of Caffa, a great trade emporium on the Crimean peninsula, came under siege by an army of Mongol warriors under the command of Janibeg. After a protracted siege during which the Mongol army was reportedly withering from the disease, they decided to use the infected corpses as a biological weapon. The corpses were catapulted over the city walls, infecting the inhabitants.[114] The Genoese traders fled, transferring the plague via their ships into the south of Europe, whence it rapidly spread. The total number of deaths worldwide from the pandemic is estimated at 75 million people, with an estimated 20 million deaths in Europe alone. There are claims[by whom?] of lesser casualties in the Mongol Empire due to superior hygiene and Oriental medicine.[citation needed]

Dominican martyrs killed by Mongols during the Mongol invasion of Poland in 1260. - Western researcher R. J. Rummel estimated that 30 million people were killed under the rule of the Mongol Empire. The population of China fell by half in fifty years of Mongol rule. Before the Mongol invasion, the territories of the Chinese dynasties reportedly had approximately 120 million inhabitants; after the conquest was completed in 1279, the 1300 census reported roughly 60 million people. While it is tempting to attribute this major decline solely to Mongol ferocity, scholars today have mixed opinions regarding this subject. Scholars such as Frederick W. Mote argue that the wide drop in numbers reflects an administrative failure to record rather than a de facto decrease, whilst others such as Timothy Brook argue that the Mongols reduced much of the south Chinese population, and very debatably of the Han Chinese population to an invisible status through cancellation of right to passports and denial of right to direct land ownership. This meant that the Chinese had to depend and be cared for chiefly by Mongols and Tartars, which also involved recruitment into the Mongol army. When possibly resisted by Muslim women in the aftermath of the Tangut princess episode, this is reported to have led to close to an infraction in the trafficking in women. Forbidden in the Jasa/Zasaq, women were distributed freely after what has been alleged in footnotes to Igor de Rachewitz edition of the Niuca Mongqol-un Tovcha´an to have been ordered tantamount sexual abuse, with two casualties alleged out of four thousand. Other historians such as William McNeill and David Morgan argue that the Bubonic Plague was the main factor behind the demographic decline during this period.[citation needed]

All conditions in the Mongol empire for women were mitigated by women´s right to divorce, and their discouragement of foot-binding, however Chinese Nationalist women continued to bind their feet. They had the right to divorce, discouraged by Confucianism, but encouraged by the Mongols as the Jasa specially ordained commerce to be for women. Women warriors existed such as Chatulun, and as were reported by an abbot, and women were sometimes in commanding roles as well during the mass executions following the end of pages.[citation needed]

- David Nicole states in The Mongol Warlords, "terror and mass extermination of anyone opposing them was a well tested Mongol tactic."[115] About half of the Russian population may have died during the invasion.[116] However, Colin McEvedy (Atlas of World Population History, 1978) estimates the population of Russia-in-Europe dropped from 7.5 million prior to the invasion to 7 million afterwards.[115] Historians estimate that up to half of Hungary's two million population at that time were victims of the Mongol invasion.[117] Rogerius, a monk who survived the Mongol invasion of Hungary, pointed out not only the genocidal element of the occupation, but also that the Mongols especially "found pleasure" in humiliating women. The fact is that the Mongols initially at least were not given to violent sexual abuse of women but liked to engage in such acts while physically clasping them in a kind of embrace.[118]

- One of the more successful tactics employed by the Mongols was to wipe out urban populations that refused to surrender. For example, after the conquest of Urgench, each Mongol warrior – in an army group that might have consisted of two tumens (units of 10,000) – was required to execute 24 people. In the Mongol invasion of Rus, almost all major cities were destroyed. If they chose to submit, the people were spared, war prisoners sometimes became part of the Mongol army to aid in future conquests.[119] In addition to intimidation tactics, the rapid expansion of the empire was facilitated by military hardiness (especially during bitterly cold winters), military skill, meritocracy, and discipline.

The influence of the Mongol Empire may prove to be even more direct — Zerjal et al. [2003][120] identify a Y-chromosomal lineage present in about 8% of the men in a large region of Asia (or about 0.5% of the men in the world). The paper suggests that the pattern of variation within the lineage is consistent with a hypothesis that it originated in Mongolia about 1,000 years ago. Such a spread would be too rapid to have occurred by diffusion, and must therefore be the result of selection. The authors propose that the lineage is carried by likely male line descendants of Genghis Khan, and that it has spread through social selection.[citation needed]

In addition to the khanates and other descendants, the Mughal royal family of South Asia are also descended from Genghis Khan: Babur's mother was a descendant — whereas his father was directly descended from Timur (Tamerlane). The word "Mughol" is an Arabic word for Mongol.

Notes

- ^ The actual foundation of this city did not occur until 1220, and served as the capital of the Mongol Empire as least until 1259.

- ^ After the death of Möngke Khan in 1259, there was no single major city in the empire, with Dadu being the capital of the Yuan Dynasty from 1272 to 1368.

References

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. p. 5.

- ^ Finlay. Pilgrim Art. p.151.

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/102315/history-of-Central-Asia/73543/Creation-of-the-Mongol-empire

- ^ «Mongolia se encomienda a Gengis Jan» Template:Es icon. El País 18.08.2007 (2007). Consultado el 19/06/2008.

- ^ Peter Turchin, Thomas D. Hall and Jonathan M. Adams, "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research Vol. 12 (no. 2). pp. 219-229 (2006).

- ^ Diamond. Guns, Germs, and Steel. p. 367.

- ^ The Mongols and Russia, by George Vernadsky

- ^ The Mongol World Empire, 1206-1370, by John Andrew Boyle

- ^ The History of China, by David Curtis Wright. p. 84.

- ^ The Early Civilization of China, by Yong Yap Cotterell, Arthur Cotterell. p. 223.

- ^ Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281 by Reuven Amitai-Preiss

- ^ Gregory G.Guzman "Were the barbarians a negative or positive factor in ancient and medieval history?", The Historian 50 (1988), 568-70.

- ^ Allsen. Culture and Conquest. p. 211.

- ^ "The Islamic World to 1600: The Golden Horde". University of Calgary. 1998. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ^ Michael Biran. Qaidu and the Rise of the Independent Mongol State in Central Asia. The Curzon Press, 1997, ISBN 0-7007-0631-3

- ^ The Cambridge History of China: Alien Regimes and Border States. p. 413.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 127.

- ^ Allsen. Culture and Conquest'. pp. xiii, 235.

- ^ Sanders. p. 300.

- ^ Saunders. History of the Mongol conquests. p. 225.

- ^ Rybatzki. p. 116.

- ^ Barfield. p. 184.

- ^ a b c d e Morgan. The Mongols. pp. 49–73.

- ^ Riasanovsky. Fundamental Principles of Mongol law. p. 83.

- ^ Ratchnevsky. p. 191.

- ^ Secret history. p. 203.

- ^ Vladimortsov. p. 74.

- ^ Weatherford. p. 70.

- ^ Morgan. pp. 99–101.

- ^ Man. Genghis Khan. p. 288.

- ^ Saunders. p. 81.

- ^ Atwood. p. 277.

- ^ Rossabi. p. 221.

- ^ Atwood. p. 509.

- ^ May. Chormaqan. p. 29.

- ^ Amitai. The Mamluk-Ilkhanid war

- ^ Grousset. p. 259.

- ^ Burgan. p. 22.

- ^ Timothy May. Chormaqan. p. 32.

- ^ Jackson. Delhi Sultanate. p. 105.

- ^ Bor. p. 186.

- ^ Atwood. p. 297.

- ^ Henthorn. Korea, the Mongol invasions.

- ^ Weatherford. p. 157.

- ^ Howorth. pp. 55-62.

- ^ a b Weatherford. p. 158.

- ^ Matthew Paris. English history (trans. by J.A.Giles). p. 348.

- ^ a b Morgan. The Mongols. p. 104.

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 95.

- ^ The Academy of Russian science and the academy of Mongolian science Tataro-Mongols in Europe and Asia. p. 89.

- ^ Weatherford. p. 163.

- ^ Man. Kublai Khan. p. 28.

- ^ a b c Atwood. p. 255.

- ^ D. Bayarsaikhan. Ezen khaaniig Ismailiinhan horooson uu (Did the Ismailis kill the Great Khan)[better source needed]

- ^ Weatherford. p. 179.

- ^ Atwood. p. 213.

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. p. 159.

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. pp. 103–104.

- ^ Guzman, Gregory G. (Spring 2010). "European captives and craftsmen among the Mongols, 1231-1255". The Historian. 72 (1): 122–150. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.2009.00259.x.

- ^ Allsen. Mongol Imperialism. p. 280.

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. p. 129.

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. pp. 132–135.

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. pp. 127–128.

- ^ Lane. p. 9.

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. p. 138.

- ^ Wassaf. p. 12.[full citation needed]

- ^ Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 109.

- ^ Barthold. Turkestan. p. 488.

- ^ L. N.Gumilev, A. Kruchki. Black legend

- ^ Barthold. Turkestan down to the Mongol invasion. p. 446.

- ^ Prawdin. Mongol Empire and its legacy. p. 302.

- ^ Weatherford. p. 120.

- ^ Man. Kublai Khan. p. 74.

- ^ Sh.Tseyen-Oidov – Ibid. p. 64.

- ^ a b Man. Kublai Khan. p. 207.

- ^ Weatherford. p. 195.

- ^ Vernadsky. The Mongols and Russia. pp. 344–366.[full citation needed]

- ^ Henryk Samsonowicz, Maria Bogucka. A Republic of Nobles. p. 179.[full citation needed]

- ^ Prawdin. [page needed]

- ^ Allsen. Culture and Conquest. pp. 32–35.

- ^ René Grousset. The Empire of the Steppes

- ^ Atwood. p. 445.

- ^ Bibliothèque nationale de France. Département des Manuscrits. Division occidentale. Nouvelle acquisition française 886, fol. 37v

- ^ d.Ohson. History of the Mongols. p.II. p. 355.[full citation needed]

- ^ Sh.Tseyen-Oidov. Genghis bogdoos Ligden khutagt khurtel (khaad). p. 81.[full citation needed]

- ^ Vernadsky – The Mongols and Russia. p. 74.

- ^ Oljeitu's letter to Philipp the Fair

- ^ J. J. Saunders The History of the Mongol conquests

- ^ Howorth. p. 145.

- ^ Atwood. p. 106.

- ^ Allsen. Culture and Conquest. p. 39.

- ^ Franke. pp. 541-550.

- ^ Vernadsky. p. 93.

- ^ Weatherford. p. 236.

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. pp. 117–118.

- ^ Prawdin. p. 379.

- ^ Halperin. p. 28.

- ^ Sverdrup. p. 109.

- ^ Sverdrup. p. 110.

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. pp. 80–81.

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. pp. 74–75

- ^ Morgan. Mongols and the Eastern Mediterranean

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. p. 75

- ^ Weatherford. p. 69.

- ^ Weatherford. p. 135.

- ^ Ezzati. The spread of Islam: the contributing factors. p. 274.

- ^ Bukharaev. Islam in Russia: the four seasons. p. 145.

- ^ Chambers, James. The Devil's Horsemen Atheneum, 1979, ISBN 0-689-10942-3

- ^ Secret history of the Mongols

- ^ Guoli Liu Chinese foreign policy in transition. p. 364

- ^ Foltz. pp. 105–106.

- ^ R. Ward, Steven (2009). Immortal: a military history of Iran and its armed forces. Georgetown University Press. p. 39. ISBN 1-58901-258-5.

- ^ Hahn, Reinhard F. (1991). Spoken Uyghur. London and Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98651-7Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Svat Soucek. A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-521-65704-0. P. 116.

- ^ a b Mongol Conquests

- ^ History of Russia, Early Slavs history, Kievan Rus, Mongol invasion

- ^ The Mongol invasion: the last Arpad kings

- ^ Life after death: approaches to a cultural and social history of Europe during the 1940s and 1950s. Richard Bessel, Dirk Schumann (2003). Cambridge University Press. p.143. ISBN 978-0-521-00922-5

- ^ The Story of the Mongols Whom We Call the Tartars= Historia Mongalorum Quo s Nos Tartaros Appellamus: Friar Giovanni Di Plano Carpini's Account of His Embassy to the Court of the Mongol Khan by Da Pian Del Carpine Giovanni and Erik Hildinger (Branden BooksApril 1996 ISBN 978-0-8283-2017-7)

- ^ Zerjal, Xue, Bertolle, Wells, Bao, Zhu, Qamar, Ayub, Mohyuddin, Fu, Li, Yuldasheva, Ruzibakiev, Xu, Shu, Du, Yang, Hurles, Robinson, Gerelsaikhan, Dashnyam, Mehdi, Tyler-Smith (2003). "The Genetic Legacy of the Mongols". American Journal of Human Genetics (72): 717–721.

Sources

- Allsen, Thomas T. (1987). Mongol Imperialism: The Policies of the Grand Qan Möngke in China, Russia, and the Islamic Lands, 1251-1259. University of California Press. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/978-0-520-05527-6|978-0-520-05527-6[[Category:Articles with invalid ISBNs]]]].

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Allsen, Thomas T. (2004). Culture and conquest in Mongol Eurasia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-60270-9.

- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven (1995). Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281. Cambridge, UK; New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46226-6.

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York, USA: Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-4671-9.

- Barfield, Thomas Jefferson (1992). The perilous frontier: nomadic empires and China. Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-55786-324-9.

- Burgan, Michael (2005). Empire of the Mongols. New York, USA: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0318-1.

- Diamond, Jared (1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York, USA: W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-6131-0.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - Finlay, Robert (2010). The Pilgrim Art: Cultures of Porcelain in World History. Berkeley, California, USA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24468-9.

- Foltz, Richard C. (1999). Religions of the Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Exchange from Antiquity to the Fifteenth Century. New York, USA: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-23338-8.

- Franke, Herbert (1994). Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368. Vol. 6. Cambridge, UK; New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: a History of Central Asia (translated from French by Naomi Walford). New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA: Rutgers University Press.

- Halperin, Charles J. (1985). Russia and the Golden Horde: The Mongol Impact on Medieval Russian History. Bloomington, Indiana, USA: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20445-3.

- Howorth, Henry H. (1965 (reprint of London edition, 1876)). History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th Century: Part I: The Mongols Proper and the Kalmuks. New York, USA: Burt Frankin.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Jackson, Peter (1978). "The dissolution of the Mongol Empire". Central Asiatic Journal. XXXII: 208–351.

- Jackson, Peter (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge, UK; New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54329-0.

- Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West: 1221-1410. Harlow, UK; New York, USA: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-36896-5.

- Lane, George (2006). Daily life in the Mongol empire. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33226-5.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, death and resurrection. New York, USA: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-36624-7.

- Man, John (2007). Kublai Khan: from Xanadu to superpower. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-81718-8.

- Morgan, David (1989). "The Mongols and the Eastern Mediterranean: Latins and Greeks in the Eastern Mediterranean after 1204". Mediterranean Historical Review. 4 (1). Tel Aviv, Illinois, USA: Routledge: 204. doi:10.1080/09518968908569567. ISSN 0951-8967.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Morgan, David (2007). The Mongols (2nd ed.). Malden, Massachusetts, USA; Oxford, UK; Carlton, Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-3539-9.

- Prawdin, Michael (pseudonym for Charol, Michael) (1940/1961). Mongol Empire. New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA: Collier-Macmillan Canada. ISBN 1-4128-0519-8.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ratchnevsky, Paul (1993). Haining, Thomas Nivison (translator) (ed.). Genghis Khan: his life and legacy. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/8780631189497|8780631189497[[Category:Articles with invalid ISBNs]][[Category:Articles with invalid ISBNs]]]].

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Rossabi, Morris (1983). China among equals: the Middle Kingdom and its neighbors, 10th-14th centuries. Berkeley, California, USA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04383-9.

- Sanders, Alan J. K. (2010). Historical dictionary of Mongolia. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6191-6.

- Saunders, John Joseph (2001). The history of the Mongol conquests. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1766-7.

- Rybatzki, Volker (2009). The early mongols: language, culture and history. Indiana University. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/97880933070578|97880933070578[[Category:Articles with invalid ISBNs]]]].

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Sverdrup, Carl (November 2010). "Numbers in Mongol Warfare". [[Journal of Medieval Military History]]. Vol. 8. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84383-596-7.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Vladimortsov, Boris (1969). The life of Chingis Khan. B. Blom.

- Weatherford, Jack (2004). Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. New York, USA: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-609-80964-4.