Roger Waters: Difference between revisions

use a lowercase intial letter after a colon in a header per MoS |

Scottywong (talk | contribs) m Changed protection level of Roger Waters: Persistent vandalism ([edit=autoconfirmed] (expires 15:09, 19 November 2012 (UTC)) [move=sysop] (indefinite)) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 15:09, 12 November 2012

Roger Waters | |

|---|---|

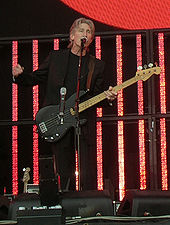

Roger Waters at The O2 Arena in 2008 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | George Roger Waters |

| Born | 6 September 1943 Great Bookham, Surrey, England, United Kingdom |

| Genres | Progressive rock, psychedelic rock, art rock, hard rock, opera |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, songwriter, composer, producer |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals, bass guitar, guitar, synthesiser, clarinet, trumpet |

| Years active | 1964-present |

| Labels | Capitol, Columbia, Sony, Harvest |

| Website | roger-waters |

George Roger Waters (born 6 September 1943) is an English musician, singer-songwriter and composer. He was a founder member of the progressive rock band Pink Floyd, serving as bassist and co-lead vocalist. Following the departure of bandmate Syd Barrett in 1968, Waters became the band's lyricist, principal songwriter and conceptual leader. The band subsequently achieved international success in the 1970s with the concept albums The Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here, Animals and The Wall. Although Waters' primary instrument in Pink Floyd was the bass guitar, he also experimented with synthesisers and tape loops and played rhythm guitar on recordings and in concerts. Amid creative differences within the group, Waters left Pink Floyd in 1985 and began a legal battle with the remaining members over their intended use of the group's name and material. They settled the dispute out of court in 1987, and nearly eighteen years had passed before he performed with Pink Floyd again. The group have sold more than 250 million albums worldwide, including 74.5 million units sold in the United States as of 2012[update].

Waters' solo career includes three studio albums: The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking (1984), Radio K.A.O.S. (1987) and Amused to Death (1992). In 1986, he contributed songs and a score to the soundtrack of the animated film When the Wind Blows based on the Raymond Briggs' book of the same name. In 1990, he staged one of the largest and most extravagant rock concerts in history, The Wall – Live in Berlin, with an official attendance of 200,000. In 1996, he was inducted into the US and the UK Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of Pink Floyd. He has toured extensively as a solo act since 1999 and played The Dark Side of the Moon in its entirety for his world tours of 2006–2008. In 2005, he released Ça Ira, an opera in three acts translated from Étienne and Nadine Roda-Gils' libretto based on the French Revolution. On 2 July 2005, he reunited with Pink Floyd bandmates Nick Mason, Richard Wright and David Gilmour for the Live 8 global awareness event; it was the group's first appearance with Waters in 24 years.

In 2010, he began The Wall Live, a worldwide tour that features a complete performance of The Wall. During this tour, at The O2 Arena in London on 12 May 2011, Gilmour and Mason once again appeared with Waters, Gilmour performing "Comfortably Numb", and Gilmour and Mason joining Waters for "Outside the Wall". Waters' tour topped international concert ticket sales for the first half of 2012, selling more than 1.4 million tickets globally.

Four times married, he is the father of three children. In 2004, he became engaged to actress and filmmaker Laurie Durning; the pair married in 2012.

1943–1964: early years

George Roger Waters was born on 6 September 1943, the younger of two boys,[1] to Mary and Eric Fletcher Waters, in Great Bookham, Surrey.[2] His father, the son of a coal miner and Labour Party activist, was a schoolteacher, a devout Christian and a Communist Party member.[3] In the early years of the Second World War, his father was a conscientious objector who drove an ambulance during the Blitz.[3] He later changed his stance on pacifism and joined the British Army, and as an officer of the 8th Royal Fusiliers died at Anzio in Italy, declared missing or presumed dead on 18 February 1944,[4] when Roger was five months old.[5] Following her husband's death, Mary, also a teacher, moved with her two sons to Cambridge and raised them there.[6] His earliest memory is of the VJ Day celebrations.[7] Mary died in 2009 at the age of 96.

Waters attended Morley Memorial Junior School in Cambridge and then the Cambridgeshire High School for Boys (now Hills Road Sixth Form College) with Roger Barrett (later to be known as Syd),[8] while his future musical partner, David Gilmour, lived nearby on the town's Mill Road, and attended the Perse School.[9] At 15, Waters was chairman of the Cambridge Youth Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (YCND),[10] having designed its publicity poster and participated in its organisation.[11] Though he was a keen sportsman and a highly regarded member of the high school's cricket and rugby teams,[12] his educational experience was lacking; according to Waters, "I hated every second of it, apart from games. The regime at school was a very oppressive one ... the same kids who are susceptible to bullying by other kids are also susceptible to bullying by the teachers."[13] Whereas Waters knew Barrett and Gilmour from his childhood in Cambridge, he met future Pink Floyd founder members Nick Mason and Richard Wright in London at the Regent Street Polytechnic (later the University of Westminster) school of architecture. Waters enrolled there in 1962[1] after a series of aptitude tests indicated he was well-suited to that field. He had initially considered a career in mechanical engineering.[14]

Subsequent personal life

In 1969, Waters married his childhood sweetheart and "girl next door"[7] Judy Trim, a successful potter; featured on the gatefold sleeve of the original release of Ummagumma, but excised from subsequent CD reissues.[15] They had no children together and divorced in 1975.[2] She later remarried; and died on 9 January 2001.[16] In 1976, he married Lady Carolyne Christie,[2] the niece of the Marquess of Zetland. His marriage to Christie produced a son, Harry Waters, a musician who has played keyboards with his father's touring band since 2006,[17] and a daughter, the model India Waters.[18] Through Harry, he has grandchildren.[7] Christie and Waters divorced in 1992.[2] In 1993, he married Priscilla Phillips;[19] their marriage ended in 2001. In 2004, he became engaged to actress and filmmaker Laurie Durning, and the two wed on 14 January 2012.[20]

1965–1985: Pink Floyd

Formation and Barrett-led period

By September 1963, Waters and Mason began losing interest in their studies,[21] and they moved into the lower flat of Stanhope Gardens, owned by Mike Leonard, a part-time tutor at the Regent Street Polytechnic.[22] Waters, Mason and Wright first played music together in the autumn of 1963,[23] in a group formed by vocalist Keith Noble and bassist Clive Metcalfe.[24] The group usually called themselves Sigma 6, but they also used the name the Meggadeaths.[11] Waters played rhythm guitar and Mason played drums, Wright played on any keyboard he could arrange to use,[25] and Noble's sister Sheilagh provided an occasional vocal accompaniment.[23] In the early years the band performed during private functions and rehearsed in a tearoom in the basement of Regent Street Polytechnic.[26]

When Metcalfe and Noble left to form their own group in September 1963,[27] the remaining members asked Barrett and guitar player Bob Klose to join.[28] By January 1964, the group became known as the Abdabs, or the Screaming Abdabs.[28] During the autumn of 1964, the band used the names Leonard's Lodgers, Spectrum Five, and eventually, the Tea Set.[29] Sometime during the autumn of 1965, the Tea Set began calling itself the Pink Floyd Sound, later, the Pink Floyd, and by early 1966,[30] Pink Floyd.[31]

By early 1966 Barrett was Pink Floyd's front-man, guitarist, and songwriter.[32] He wrote or co-wrote all but one track of their debut LP The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, released in August 1967.[33] Waters contributed the song "Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk" (his first sole writing credit) to the album.[34] However, by late 1967, Barrett's deteriorating mental health and increasingly erratic behaviour,[35] rendered him "unable or unwilling"[36] to continue in his capacity as Pink Floyd's singer-songwriter and lead guitarist.[33] Working with Barrett eventually proved too difficult, so in early March 1968 Pink Floyd met with managers Peter Jenner and Andrew King of Blackhill Enterprises to discuss the band's future. Barrett agreed to leave Pink Floyd, and the band "agreed to Blackhill's entitlement in perpetuity" with regard to "past activities".[37] The band's new manager Steve O'Rourke made a formal announcement about the departure of Barrett and the arrival of David Gilmour in April 1968.[38]

Waters-led period

Filling the void left by Barrett's departure in March 1968, Waters began to chart Pink Floyd's artistic direction. He became the principal songwriter, lyricist, and co-lead vocalist (along with Gilmour, and at times, Wright), and would remain the band's dominant creative figure until his departure in 1985.[39] He wrote the lyrics to the five Pink Floyd albums preceding his own departure, starting with The Dark Side of the Moon (1973) and ending with The Final Cut (1983), while exerting progressively more creative control over the band and its music. Every Waters studio album since The Dark Side of the Moon has been a concept album.[40] With lyrics written entirely by Waters, The Dark Side of the Moon was one of the most commercially successful rock albums of all time. It spent 736 straight weeks on the Billboard 200 chart until July 1988 and sold over 40 million copies worldwide. It was continuing to sell over 8,000 units every week as of 2005.[41] According to Pink Floyd biographer Glen Povey, Dark Side is the world's second best-selling album, and the United States' 21st best-selling album of all time.[42]

Waters produced thematic ideas that became the impetus for the Pink Floyd concept albums The Dark Side of the Moon (1973), Wish You Were Here (1975), Animals (1977), and The Wall (1979)—written largely by Waters—and The Final Cut (1983)—written entirely by Waters.[43] He referred or alluded to the cost of war and the loss of his father throughout his work, from "Corporal Clegg" (A Saucerful of Secrets, 1968) and "Free Four" (Obscured by Clouds, 1972) to "Us and Them" from The Dark Side of the Moon, "When the Tigers Broke Free", first used in the feature film, The Wall (1982), later included with "The Fletcher Memorial Home" on The Final Cut, an album dedicated to his father.[44] The theme and composition of The Wall was influenced by his upbringing in an English society depleted of men after the Second World War.[45]

I think things like "Comfortably Numb" were the last embers of mine and Roger's ability to work collaboratively together.

The double album The Wall was written almost entirely by Waters and is largely based on his life story,[47] and having sold over 23 million RIAA certified units in the US as of 2010, is one of the top three best-selling albums of all-time in America, according to RIAA.[48] Pink Floyd hired Bob Ezrin to co-produce the album, and cartoonist Gerald Scarfe to illustrate the album's sleeve art.[49] The band embarked on The Wall Tour of LA, New York, London and Dortmund. The last band performance of The Wall was on 16 June 1981, at Earls Court London, and this was Pink Floyd's last appearance with Waters until the band's brief reunion at 2 July 2005 Live 8 concert in London's Hyde Park, 24 years later.[50]

In March 1983, the last Waters–Gilmour–Mason collaboration, The Final Cut, was released. The album was subtitled: "A requiem for the post-war dream by Roger Waters, performed by Pink Floyd".[51] Waters is credited with writing all the lyrics as well as all the music on the album. His lyrics to the album were critical of the Conservative Party government of the day and mention Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher by name.[52] At the time Gilmour did not have any material for the album, so he asked Waters to delay the recording until he could write some songs, but Waters refused.[53] According to Mason, after power struggles within the band and creative arguments about the album, Gilmour's name "disappeared" from the production credits, though he retained his pay.[54] Rolling Stone magazine gave the album five stars, with Kurt Loder calling it "a superlative achievement"[55] and "art rock's crowning masterpiece".[56] Loder viewed the work as "essentially a Roger Waters solo album".[57]

Amidst creative differences within the group, Waters left Pink Floyd in 1985, and began a legal battle with the remaining band members regarding their continued use of the name and material.[58] In December 1985 Waters "issued a statement to EMI and CBS invoking the 'Leaving Member' clause" on his contract. In October 1986, he initiated High Court proceedings to formally dissolve the Pink Floyd partnership. In his submission to the High Court he called Pink Floyd a "spent force creatively".[59] Gilmour and Mason opposed the application and announced their intention to continue as Pink Floyd. Waters claims to have been forced to resign much like Wright some years earlier, and he decided to leave Pink Floyd based on legal considerations, stating " ... because, if I hadn't, the financial repercussions would have wiped me out completely."[60] In December 1987, an agreement between Waters and Pink Floyd was reached.[58] According to Mason:

We eventually formalised a settlement with Roger. On Christmas Eve, 1987, ... David and Roger convened for a summit meeting on the houseboat [the Astoria] with Jerome Walton, David's accountant. Jerome painstakingly typed out the bones of a settlement. Essentially—although there was far more complex detail—the arrangement allowed Roger to be freed from his arrangement with Steve [O'Rourke], and David and me to continue working under the name Pink Floyd. In the end the court accepted Jerome's version as the final and binding document and duly stamped it.[61]

Waters was released from his contractual obligation with O'Rourke, and he retained the copyrights to The Wall concept and his trademarked inflatable pig.[62] The Gilmour-led Pink Floyd released two studio albums: A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987), and The Division Bell (1994). As of 2006, it is estimated that Pink Floyd have sold over 250 million albums worldwide,[63] including 74.5 million RIAA certified units sold in the US.[64]

1984–present: solo career

1984–1996

Following the release of The Final Cut, Waters embarked on a solo career that produced three concept albums and a movie soundtrack. In 1984, he released his first solo album, The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking, a project about a man's dreams across one night that dealt with Waters' feelings about his failed marriage to Judy Trim, sex, and the pros and cons of monogamy and family life versus "the call of the wild".[65] In the end the character, Reg, chooses love and matrimony over promiscuity. The album featured guitarist Eric Clapton, jazz saxophonist David Sanborn, and artwork by Scarfe.[65] Rolling Stone's Kurt Loder described The Pros And Cons of Hitch Hiking as a "strangely static, faintly hideous record",[66] Rolling Stone rated the album a "rock bottom" one star."[65] Years later, Mike DeGagne of Allmusic praised the album for its, "ingenious symbolism" and "brilliant use of stream of consciousness within a subconscious realm", rating it four out of five stars.[67] Waters began touring in support of the new album, aided by Clapton, a new band, new material, and a selection of Pink Floyd favourites. Waters débuted his tour in Stockholm on 16 June 1984. Poor ticket sales plagued the tour,[68] and some of the larger venues had to be cancelled. By his own estimate, he lost £400,000 on the tour.[69] In March 1985, Waters went to North America to play smaller venues with the Pros and Cons Plus Some Old Pink Floyd Stuff — North America Tour 1985. The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking has been certified Gold by the RIAA.[70]

In 1986, Waters contributed songs and a score to the soundtrack of the animated movie When the Wind Blows, based on the Raymond Briggs book of the same name. His backing band featuring Paul Carrack was credited as The Bleeding Heart Band.[71] In 1987, Waters released Radio K.A.O.S., a concept album based on a mute man named Billy from an impoverished Welsh mining town who has the ability to physically tune into radio waves in his head. Billy first learns to communicate with a radio DJ, and eventually to control the world's computers. Angry at the state of the world in which he lives, he simulates a nuclear attack. Waters followed the release with a supporting tour also in 1987.[72]

In November 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, and in July 1990 Waters staged one of the largest and most elaborate rock concerts in history,[73] The Wall – Live in Berlin, on the vacant terrain between Potsdamer Platz and the Brandenburg Gate. The show reported an official attendance of 200,000, though some estimates are as much as twice that, with approximately one billion television viewers.[74] Leonard Cheshire asked him to do the concert to raise funds for charity. Waters' group of musicians included Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, Cyndi Lauper, Bryan Adams, Scorpions, and Sinéad O'Connor. Waters also used an East German symphony orchestra and choir, a Soviet marching band, and a pair of helicopters from the US 7th Airborne Command and Control Squadron. Designed by Mark Fisher, the Wall was 25 metres tall and 170 metres long and was built across the set. Scarfe's inflatable puppets were recreated on an enlarged scale, and although many rock icons received invitations to the show, Gilmour, Mason, and Wright, did not.[75] Waters released a concert double album of the performance which has been certified platinum by RIAA.[70]

In 1990, Waters hired manager Mark Fenwick and left EMI for a worldwide deal with Columbia. He released his third studio album, Amused to Death, in 1992. The record is heavily influenced by the events of the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 and the Gulf War, and a critique of the notion of war becoming the subject of entertainment, particularly on television. The title was derived from the book Amusing Ourselves to Death by Neil Postman. Patrick Leonard, who had also worked on A Momentary Lapse of Reason, co-produced the album. Jeff Beck played lead guitar on many of the album's tracks, which were recorded with an impressive cast of musicians at ten different recording studios.[76] It is Waters' most critically acclaimed solo recording, garnering some comparison to his previous work with Pink Floyd.[77] Waters described the record as, a "stunning piece of work", ranking the album with Dark Side Of The Moon and The Wall as one of the best of his career.[78] The album had one hit, the song "What God Wants, Pt. 1", which reached number 35 in the UK in September 1992 and number 5 on Billboard's Mainstream Rock Tracks chart in the US.[79] Amused to Death was certified Silver by the British Phonographic Industry.[80] Sales of Amused to Death topped out at around one million and there was no tour in support of the album. Waters would first perform material from it seven years later during his In the Flesh tour.[81] In 1996, Waters was inducted into the US and UK Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of Pink Floyd.[82]

1999–2004

In 1999, after a nearly 12-year hiatus from touring, and a seven-year absence from the music industry, Waters embarked on the In the Flesh Tour, performing both solo and Pink Floyd material. The tour was a financial success in the US and though Waters had booked mostly smaller venues, tickets sold so well that many of the concerts were upgraded to larger ones.[83] The tour eventually stretched across the world and would span three years. A concert film was released on CD and DVD, named In the Flesh Live. During the tour, he played two new songs "Flickering Flame" and "Each Small Candle" as the final encore to many of the shows. In June 2002, he completed the tour with a performance in front of 70,000 people at the Glastonbury Festival of Performing Arts, playing 15 Pink Floyd songs and five songs from his solo catalogue.[83]

Miramax announced in mid-2004 that a production of The Wall was to appear on Broadway with Waters playing a prominent role in the creative direction. Reports stated that the musical contained not only the original tracks from The Wall, but also songs from Dark Side of the Moon, Wish You Were Here and other Pink Floyd albums, as well as new material.[84] On the night of 1 May 2004, recorded extracts from the opera, including its overture, were played on the occasion of the Welcome Europe celebrations in the accession country of Malta. Gert Hof mixed recorded excerpts from the opera into a continuous piece of music which was played as an accompaniment to a large light and fireworks display over Grand Harbour in Valletta.[85] In July 2004, Waters released two new tracks on the Internet: "To Kill the Child", inspired by the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and "Leaving Beirut", "inspired by his travels in the Middle East as a teenager".[86] The lyrics to "Leaving Beirut" are highly critical of former US President George W. Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair.

2005–present

In July 2005, Waters reunited with Mason, Wright, and Gilmour for what would be their final performance together at the 2005 Live 8 concert in London's Hyde Park, Pink Floyd's only appearance with Waters since their final performance of The Wall at Earls Court London 24 years earlier.[87] They played a 23-minute set consisting of "Speak to Me/Breathe"/"Breathe (Reprise)", "Money", "Wish You Were Here", and "Comfortably Numb". Waters told the Associated Press that while the experience of playing with Pink Floyd again was positive, the chances of a bona fide reunion would be "slight" considering his and Gilmour's continuing musical and ideological differences.[88] Though Waters had differing ideas about which songs they should play, he "agreed to roll over for one night only",[89] Gilmour told the Associated Press, "The rehearsals convinced me it wasn't something I wanted to be doing a lot of. There have been all sorts of farewell moments in people's lives and careers which they have then rescinded, but I think I can fairly categorically say that there won't be a tour or an album again that I take part in. It isn't to do with animosity or anything like that. It's just that ... I've been there, I've done it."[90] In November 2005, Pink Floyd were inducted into the UK Music Hall of Fame by Pete Townshend of The Who.[91]

In September 2005, he released Ça Ira (pronounced [sa iˈʁa], French for "it will be fine"; Waters added the subtitle, "There is Hope"), an opera in three acts translated from the late Étienne Roda-Gil's French libretto based on the historical subject of the French Revolution.[92] Ça Ira was released as a double CD album, featuring baritone Bryn Terfel, soprano Ying Huang and tenor Paul Groves.[93] Set during the early French Revolution, the original libretto was co-written in French by Roda-Gil and his wife Nadine Delahaye. Waters had begun rewriting the libretto in English in 1989,[94] and said about the composition: "I've always been a big fan of Beethoven's choral music, Berlioz and Borodin ... This is unashamedly romantic and resides in that early 19th-century tradition, because that's where my tastes lie in classical and choral music."[95] Waters appeared on television to discuss the opera, but the interviews often focused instead on his relationship with Pink Floyd, something Waters would "take in stride", a sign Pink Floyd biographer Mark Blake believes to be, "a testament to his mellower old age or twenty years of dedicated psychotherapy".[95] Ça Ira reached number 5 on the Billboard Classical Music Chart in the United States.[96]

In June 2006, he commenced The Dark Side of the Moon Live tour, a two-year, world-spanning effort that began in Europe in June and North America in September. The first half of the show featured both Pink Floyd songs and Waters' solo material, while the second half included a complete live performance of the 1973 Pink Floyd album The Dark Side of the Moon, the first time in over three decades that Waters had performed the album. The shows ended with an encore from the third side of The Wall. He utilised elaborate staging by concert lighting designer Marc Brickman complete with laser lights, fog machines, flame throwers, psychedelic projections, and inflatable floating puppets (Spaceman and Pig) controlled by a "handler" dressed as a butcher, and a full 360-degree quadraphonic sound system was used. Nick Mason joined Waters for The Dark Side of the Moon set and the encores on select 2006 tour dates.[97] Waters continued touring in January 2007 in Australia and New Zealand, then Asia, Europe, South America, and back to North America in June.

In March 2007, the Waters song, "Hello (I Love You)" was featured in the science fiction film The Last Mimzy. The song plays over the film's end credits. He released it as a single, on CD and via download, and described it as, "a song that captures the themes of the movie, the clash between humanity's best and worst instincts, and how a child's innocence can win the day".[98] He performed at California's Coachella Festival in April 2008 and was to be among the headlining artists performing at Live Earth 2008 in Mumbai, India in December 2008,[99] but that concert was cancelled in light of the 26 November terrorist attacks in Mumbai.[100]

In March 2008, Roger Waters reunited with Argentine musician Gustavo Cerati in New York to collaborate on a song to benefit the ALAS Foundation. The session was held in the Looking Glass Studios belonging to the minimalist composer Philip Glass. Until this day, is unknown what happened with that recording.[101]

He confirmed the possibility of an upcoming solo album which "might be called" Heartland, and has said he has numerous songs written (some already recorded) that he intends to release when they are a complete album.[102] In June 2010, Waters released a cover of "We Shall Overcome", a protest song derived from the refrain of a gospel hymn published by Charles Albert Tindley in 1901. He performed with David Gilmour at the Hoping Foundation Benefit Evening in July 2010.[103] The four-song set included: "To Know Him Is to Love Him", which was played in early Pink Floyd sound checks, followed by "Wish You Were Here", "Comfortably Numb", and "Another Brick in the Wall (Part Two)".[104]

In September 2010, he commenced The Wall Live tour, an updated version of the original Pink Floyd shows, featuring a complete performance of The Wall.[105] According to Cole Moreton of the Daily Mail, "The touring version of Pink Floyd's The Wall is one of the most ambitious and complex rock shows ever ...",[106] and it is estimated that the tour cost £37 million to stage.[106] Waters told the Associated Press that The Wall Tour will likely be his last, stating: "I'm not as young as I used to be. I'm not like B.B. King, or Muddy Waters. I'm not a great vocalist or a great instrumentalist or whatever, but I still have the fire in my belly, and I have something to say. I have a swan song in me and I think this will probably be it."[107] At the O2 Arena in London on 12 May 2011, Gilmour and Mason once again appeared with Waters and Gilmour performing "Comfortably Numb", and Gilmour and Mason joining Waters for "Outside the Wall".[108] For the first half of 2012, Waters' tour topped worldwide concert ticket sales having sold more than 1.4 million tickets globally.[109]

Activism

After the 2004 Indian Ocean Earthquake and subsequent tsunami disaster, Waters performed "Wish You Were Here" with Eric Clapton during a benefit concert on the American network NBC.[110] He was outspoken against the Hunting Act of 2004, and performed a concert for, and attended marches supporting, the Countryside Alliance. Waters explained:

I've become disenchanted with the political and philosophical atmosphere in England. The anti-hunting bill was enough for me to leave England. I did what I could, I did a concert and one or two articles, but it made me feel ashamed to be English. I was in Hyde Park for both the Countryside Alliance marches. There were hundreds of thousands of us there. Good, honest English people. That's one of the most divisive pieces of legislation we've ever had in Great Britain. It's not a case of whether or not I agree with fox hunting, but I will defend to the hilt their right to take part in it.[86]

In October 2005, he clarified: "I come back to the UK quite often. I didn't leave as a protest against the hunting ban; I was following a child in the wake of a divorce."[111] After leaving Britain, he moved to Long Island in New York with his fiancé Laurie Durning.[112] In July 2007, he played on the American leg of the Live Earth concert, an international multi-venue concert aimed at raising awareness about global climate change, featuring the Trenton Youth Choir and his trademarked inflatable pig. Waters told David Fricke why he thinks The Wall is still relevant today:

The loss of a father is the central prop on which [The Wall] stands. As the years go by, children lose their fathers again and again, for nothing. You see it now with all these fathers, good men and true, who lost their lives and limbs in Iraq for no reason at all. I've done Bring The Boys Back Home in my encore on recent tours. It feels more relevant and poignant to be singing that song now than it did in 1979.[113]

In 2007, Waters became a spokesman for Millennium Promise, a non-profit organisation that helps fight extreme poverty and malaria. He wrote an opinion piece for CNN in support of the topic.[114] Waters has been outspoken about Middle Eastern politics and in June 2009, he openly opposed the Israeli West Bank barrier, calling it an "obscenity" that "should be torn down".[115] In December 2009, Waters pledged his support to the Gaza Freedom March[116] and in March 2011, he announced that he had joined the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement against Israel.[117]

Equipment and instruments

Waters' primary instrument in Pink Floyd was the electric bass guitar. He briefly played a Höfner bass but replaced it with a Rickenbacker RM-1999/4001S,[28] until 1970 when it was stolen along with the rest of the band's equipment in New Orleans. He began using Fender Precision Basses in 1968, originally alongside the Rickenbacker, and then exclusively after the Rickenbacker was lost in 1970. First seen at a concert in Hyde Park, London in July 1970, the black P-Bass was rarely used until April 1972 when it became his main stage guitar and as of 2 October 2010, the basis for a Fender Artist Signature model.[118] Waters endorses RotoSound Jazz Bass 77 flat-wound strings.[119] Throughout his career he has used Selmer, WEM, Hiwatt and Ashdown amplifiers but has recently settled on using Ampeg for the last few major tours, also employing delay, tremolo, chorus, stereo panning and phaser effects in his bass playing.[120]

Waters experimented with the EMS Synthi A and VCS 3 synthesisers on Pink Floyd pieces such as "On the Run",[121] "Welcome to the Machine",[122] and "In the Flesh?"[123] He played electric and acoustic guitar on Pink Floyd tracks using Fender, Martin, Ovation and Washburn guitars.[120] He played electric guitar on the Pink Floyd song "Sheep", from Animals,[124] and acoustic guitar on several Pink Floyd recordings, such as "Pigs on the Wing 1 & 2", also from Animals,[125] "Southampton Dock" from The Final Cut,[126] and on "Mother" from The Wall.[127] A Binson Echorec 2 echo effect was used on his bass-guitar lead track "One of These Days".[128] Waters has also played clarinet during concert performances of "Outside the Wall".[129]

Discography

- The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking (1984)

- Radio K.A.O.S. (1987)

- Amused to Death (1992)

- Ça Ira (2005)

Citations

- ^ a b Povey 2008, p. 320.

- ^ a b c d Fitch 2005, p. 335.

- ^ a b Blake 2008, p. 13.

- ^ "Casualty Details". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Manning 2006, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b c "Desert Island Discs, Roger Waters". BBC Radio 4. 29 May 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ Watkinson & Anderson 1991, p. 15.

- ^ Watkinson & Anderson 1991, p. 18.

- ^ Mason 2005, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Povey 2008, p. 13.

- ^ Watkinson & Anderson 1991, p. 23.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 14–19.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 36.

- ^ Mabbett 2010, p. 50.

- ^ Cooper, Emmanuel (25 January 2001). "Judy Trim". The Independent. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ Povey 2008, pp. 335–339.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 258.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 348.

- ^ MacNeil, Jason. "Roger Waters Marries Laurie Durning, Talks of 'Clinging to Pink Floyd Trademark'". spinner.com. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 40.

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 20.

- ^ a b Mason 2005, p. 17.

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Mason 2005, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Mason 2005, pp. 13–18.

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Povey 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Povey 2008, pp. 18, 28.

- ^ Povey 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Mason 2005, pp. 30–37.

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 87.

- ^ a b Mason 2005, pp. 87–107.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 91.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 90–114.

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 129.

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 105.

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 106.

- ^ Mason 2005, pp. 106–107, 160–161, 265, 278.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 3, 9, 113, 156, 242, 279, 320, 398.

- ^ Titus, Christa; Waddell, Ray (2005). "Floyd's 'Dark Side' Celebrates Chart Milestone". Billboard.com. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Povey 2008, p. 345.

- ^ Mason 2005, pp. 265–269.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 294.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 294–295, 351.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 275.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 260.

- ^ "RIAA GOLD & PLATINUM Top 100 Albums". RIAA. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Povey & Russell 1997, p. 185.

- ^ Povey 2008, p. 230.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 294–299.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 295.

- ^ Mason 2005, pp. 264–270.

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 262.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 300.

- ^ Loder, Kurt (14 April 1983). "Pink Floyd: The Final Cut (Toshiba)". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ a b Povey 2008, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Povey 2008, pp. 221, 237, 240–241, 246.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 312–313.

- ^ Mason 2005, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Manning 2006, pp. 139.

- ^ Pink Floyd Reunion Tops Fans' Wish List in Music Choice Survey, Bloomberg, 26 September 2007, retrieved 25 May 2012; "Pink Floyd's a dream, Zeppelin's a reality". Richmond Times-Dispatch. 28 September 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2012.; "Pink Floyd biography". Official site. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ "Top Selling Artists". RIAA. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Schaffner 1991, pp. 272–273.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 305–306.

- ^ DeGagne, Mike. "The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking". Allmusic. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 332–333.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 309.

- ^ a b "RIAA Certifications". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ Fitch 2005, p. 36.

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 131.

- ^ Povey & Russell 1997, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 346.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 342–347.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 348–349.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 347–352.

- ^ Manning 2006, pp. 141, 252.

- ^ "Roger Waters: Billboard Singles". Allmusic. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ "BPI Certifications". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Povey 2008, pp. 323–324.

- ^ "Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Pink Floyd". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ a b Povey 2008, pp. 329–334.

- ^ "Pink Floyd's Wall Broadway bound". BBC News. 5 August 2004. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Povey 2008, p. 334.

- ^ a b Blake 2008, p. 391.

- ^ Povey 2008, pp. 237, 266–267.

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 308.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 382–383.

- ^ "Gilmour says no Pink Floyd reunion". MSNBC. 9 September 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 386

- ^ Tsioulcas, Anastasia (27 August 2005). "Waters' New Concept". Billboard: 45. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Povey 2008, pp. 324–325.

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 256.

- ^ a b Blake 2008, p. 392.

- ^ "Roger Waters: Ca Ira". Billboard.com. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ Povey 2008, pp. 319, 334–338.

- ^ "Reminder – Pink Floyd Rock Icon Roger Waters Records "Hello (I Love You)", an Original Song for New Line Cinema's "The Last Mimzy"". Marketwire. January 2007. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ "Pink Floyd's Roger Waters to join Bon Jovi at Live Earth India". NME News. 21 November 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (1 December 2008). "Live Earth India cancelled after Mumbai attacks". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ http://www.rollingstone.com.ar/995327 Cerati y Roger Waters, juntos - RollingStone Argentina

- ^ Brown, Mark (25 April 2008). "Read the complete Roger Waters interview". Rocky Mountain News. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Youngs, Ian (15 October 2010). "Pink Floyd may get back together for charity". BBC News. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Kreps, David (12 July 2010). "Pink Floyd's Gilmour and Waters Stun Crowd With Surprise Reunion". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Jones, Rebecca (27 May 2010). "Pink Floyd's Roger Waters revisits The Wall". BBC News. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ a b Moreton, Cole (7 November 2010). "Backstage with Roger Waters as he prepares for The Wall spectacular $60 million live show". Daily Mail. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Butler, Will (12 April 2010). "Roger Waters Revisits 'The Wall' For Final Anniversary Tour". NPR. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ^ "Pink Floyd bandmates reunite at Roger Waters concert". www.viagogo.com. 16 May 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ "Roger Waters tops worldwide ticket sales for 2012". BBC News. Retrieved 14 July 2012

- ^ "Stars lend a hand for tsunami relief". MSNBC. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ "Roger Waters: French Revolution". The Independent. 4 October 2005. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 391–392.

- ^ Fricke 2009, p. 74.

- ^ Waters, Roger (11 June 2007). "Waters: Something can be done about extreme poverty". CNN.com. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ Thil, Scott (2 June 2009). "Roger Waters to Israel: Tear Down the Wall". Wired News. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ "EXCLUSIVE...Pink Floyd's Roger Waters Speaks Out in Support of Gaza Freedom March, Blasts Israeli-Egyptian "Siege" of Gaza". Democracy Now!. 30 December 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ Goodman, Amy (6 March 2011). "Roger Waters voices support for Israel boycott". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ "Roger Waters Precision Bass". Fender.com. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ^ "Rotosound Endorsees". Rotosound. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ a b Fitch 2005, pp. 416–430, 441–445.

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 169.

- ^ Fitch 2005, p. 324.

- ^ Fitch & Mahon 2006, p. 71.

- ^ Fitch 2005, p. 285.

- ^ Fitch 2005, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Fitch 2005, p. 295.

- ^ Fitch 2005, p. 213.

- ^ Mabbett 1995, p. 39.

- ^ Fitch 2005, p. 232.

Sources

- Blake, Mark (2008). Comfortably Numb: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd (1st US paperback ed.). Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81752-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fitch, Vernon (2005). The Pink Floyd Encyclopedia (Third ed.). Collector's Guide Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-1-894959-24-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fitch, Vernon; Mahon, Richard (2006). Comfortably Numb-A History of "The Wall" - Pink Floyd 1978–1981 (1st ed.). PFA Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-9777366-0-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fricke, David (December 2009). "Roger Waters: Welcome to my Nightmare ... Behind The Wall". Mojo Magazine. 193. Emap Metro: pp.68–84.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mabbett, Andy (1995). The complete guide to the music of Pink Floyd (1st UK paperback ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-4301-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mabbett, Andy (2010). Pink Floyd – The Music and the Mystery (1st UK paperback ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84938-370-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Manning, Toby (2006). The Rough Guide to Pink Floyd (1st US paperback ed.). Rough Guides Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84353-575-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mason, Nick (2005). Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd (1st US paperback ed.). Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-4824-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Povey, Glen (2008). Echoes: the complete history of Pink Floyd (2nd UK paperback ed.). 3C Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-9554624-1-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Povey, Glen; Russell, Ian (1997). Pink Floyd: in the flesh, the complete performance history (1st US paperback ed.). St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-9554624-0-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schaffner, Nicholas (1991). Saucerful of Secrets: the Pink Floyd odyssey (1st US paperback ed.). Dell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-385-30684-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Watkinson, Mike; Anderson, Pete (1991). Crazy diamond: Syd Barrett & the dawn of Pink Floyd (1st UK paperback ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84609-739-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Di Perna, Alan (2002). Guitar World Presents Pink Floyd. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-634-03286-8.

- Fitch, Vernon (2001). Pink Floyd: The Press Reports 1966–1983. Collector's Guide Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-896522-72-2.

- Harris, John (2005). The Dark Side of the Moon: The Making of the Pink Floyd Masterpiece. Da Capo. ISBN 978-0-306-81342-9.

- Hiatt, Brian (September 2010). "Back to The Wall". 1114. Rolling Stone: pp. 50–57.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - MacDonald, Bruno (1997). Pink Floyd: through the eyes of ... the band, its fans, friends, and foes. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80780-0.

- Mabbett, Andy; Mabbett, Miles (1994). Pink Floyd : the visual documentary. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-1444-5.

- Miles, Barry (1982). Pink Floyd: A Visual Documentary by Miles. New York: Putnam Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-399-41001-7.

- Scarfe, Gerald (2010). The Making of Pink Floyd: The Wall (1st US paperback ed.). Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81997-1.

- Simmons, Sylvie (December 1999). "Pink Floyd: The Making of The Wall". Mojo Magazine. 73. London: Emap Metro: pp. 76–95.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help)

External links

![]() Media related to Roger Waters at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Roger Waters at Wikimedia Commons

- Roger Waters Official website

- Roger Waters Facebook page to support The Wall live tour 2010–2012

- Roger Waters Tour and Tickets 2012

- Roger Waters Blog

- Roger Waters companies grouped at OpenCorporates

- Use dmy dates from May 2012

- 1943 births

- Alumni of the University of Westminster

- British anti-war activists

- British expatriates in the United States

- Capitol Records artists

- Columbia Records artists

- Critics of religions

- English atheists

- English expatriates in the United States

- English experimental musicians

- English male singers

- English rock bass guitarists

- English rock guitarists

- English rock singers

- English singer-songwriters

- English socialists

- Grammy Award-winning artists

- Living people

- Nonviolence advocates

- Opera composers

- People from Leatherhead

- Pink Floyd members

- Religious skeptics

- Rhythm guitarists

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees

- The Wall (rock opera)

- BAFTA winners (people)

- Roger Waters

- English record producers