Bill Richardson: Difference between revisions

WikiHogan654 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

|||

| Line 182: | Line 182: | ||

==Post-gubernatorial career== |

==Post-gubernatorial career== |

||

In 2011, Richardson joined the boards of [[APCO Worldwide]] company Global Political Strategies as chairman,<ref>APCO Worldwide (2011). [http://www.apcoworldwide.com/content/news/press_releases2011/bill_richardson0223.aspx Former New Mexico Governor, Energy Secretary Bill Richardson joins APCO]. Retrieved May 5, 2011.</ref> the [[World Resources Institute]],<ref>World Resources Institute (2011). [http://www.wri.org/press/2011/04/former-governor-bill-richardson-joins-wris-board-directors Former Governor Bill Richardson Joins WRI's Board of Directors]. Retrieved May 5, 2011.</ref> the [[National Council for Science and the Environment]],<ref>NCSE (2011). [http://www.ncseonline.org/former-governor-bill-richardson-elected-ncse-board-directors Former Governor Bill Richardson Elected to NCSE Board of Directors]. Retrieved May 5, 2011.</ref> the [[National Institute for Civil Discourse]] at the [[University of Arizona]],<ref>National Institute for Civil Discourse (2011). [http://nicd.arizona.edu/node/21 Governor Bill Richardson]. Retrieved May 5, 2011.</ref> and [[Abengoa]] (international advisory board).<ref>Abengoa (2011). [http://www.abengoa.es/corp/web/en/noticias_y_publicaciones/noticias/historico/noticias/2011/03_marzo/abg_20110316.html Bill Richardson, former Governor of New Mexico, joins Abengoa’s International Advisory Board]. Retrieved May 5, 2011.</ref> He was also appointed as a special envoy for the [[Organization of American States]].<ref>Huffington Post (2011). [http://www.huffingtonpost.com/huff-wires/20110111/us-richardson-oas/ Richardson named envoy for Org. of American States]. Retrieved May 5, 2011.</ref> |

In 2011, Richardson joined the boards of [[APCO Worldwide]] company Global Political Strategies as chairman,<ref>APCO Worldwide (2011). [http://www.apcoworldwide.com/content/news/press_releases2011/bill_richardson0223.aspx Former New Mexico Governor, Energy Secretary Bill Richardson joins APCO]. Retrieved May 5, 2011.</ref> the [[World Resources Institute]],<ref>World Resources Institute (2011). [http://www.wri.org/press/2011/04/former-governor-bill-richardson-joins-wris-board-directors Former Governor Bill Richardson Joins WRI's Board of Directors]. Retrieved May 5, 2011.</ref> the [[National Council for Science and the Environment]],<ref>NCSE (2011). [http://www.ncseonline.org/former-governor-bill-richardson-elected-ncse-board-directors Former Governor Bill Richardson Elected to NCSE Board of Directors]. Retrieved May 5, 2011.</ref> the [[National Institute for Civil Discourse]] at the [[University of Arizona]],<ref>National Institute for Civil Discourse (2011). [http://nicd.arizona.edu/node/21 Governor Bill Richardson]. Retrieved May 5, 2011.</ref> and [[Abengoa]] (international advisory board).<ref>Abengoa (2011). [http://www.abengoa.es/corp/web/en/noticias_y_publicaciones/noticias/historico/noticias/2011/03_marzo/abg_20110316.html Bill Richardson, former Governor of New Mexico, joins Abengoa’s International Advisory Board]. Retrieved May 5, 2011.</ref> He was also appointed as a special envoy for the [[Organization of American States]].<ref>Huffington Post (2011). [http://www.huffingtonpost.com/huff-wires/20110111/us-richardson-oas/ Richardson named envoy for Org. of American States]. Retrieved May 5, 2011.</ref> |

||

In 2012, Richardson joined the advisory board of [[Grow Energy]], a startup company founded by young entrepreneurs from [[Redondo Beach, California]], which is utilizing algae as a clean and environmentally-beneficial electricity resource.<ref>Grow Energy, Inc. [http://www.growenergy.org/company]. Retrieved December 20, 2012.</ref> |

|||

==Publications== |

==Publications== |

||

Revision as of 08:10, 20 December 2012

This biographical article is written like a résumé. (July 2012) |

Bill Richardson | |

|---|---|

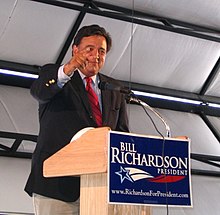

Richardson at an event in Kensington, New Hampshire, March 18, 2006 | |

| 30th Governor of New Mexico | |

| In office January 1, 2003 – January 1, 2011 | |

| Lieutenant | Diane Denish |

| Preceded by | Gary Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Susana Martinez |

| 9th United States Secretary of Energy | |

| In office August 18, 1998 – January 20, 2001 | |

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Federico Peña |

| Succeeded by | Spencer Abraham |

| 21st United States Ambassador to the United Nations | |

| In office February 13, 1997 – August 18, 1998 | |

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Madeleine Albright |

| Succeeded by | Richard Holbrooke |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New Mexico's 3rd district | |

| In office January 3, 1983 – February 13, 1997 | |

| Preceded by | District Created |

| Succeeded by | William Redmond |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Blaine Richardson III November 15, 1947 Pasadena, California |

| Political party | Democratic Party |

| Spouse | Barbara Richardson |

| Alma mater | Tufts University |

| Profession | Diplomat Business consultant |

William Blaine "Bill" Richardson III (born November 15, 1947) is an American politician who served as the 30th Governor of New Mexico from 2003 to 2011. Before being elected governor, Richardson served in the Clinton administration as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations and Energy Secretary. Richardson has also served as a U.S. Congressman, chairman of the 2004 Democratic National Convention, and chairman of the Democratic Governors Association. On December 3, 2008, then-President-elect Barack Obama designated Richardson for appointment to the cabinet-level position of Commerce Secretary.[1] On January 4, 2009, Richardson announced his decision to withdraw his nomination because of an investigation into possibly improper business dealings in New Mexico.[2][3][4] In August 2009, federal prosecutors dropped the pending investigation against the governor, and there was speculation in the media regarding Richardson's career, as his second and final term as New Mexico governor concluded.[5]

Early life and education

Bill Richardson was born in Pasadena, California.[6][7] His father, William Blaine Richardson, Jr. (died in 1972), who was of half Anglo-American and half Mexican descent, was an American Citibank executive[6][7] who grew up in Boston, Massachusetts[6] and lived and worked in Mexico City.[7] His mother, María Luisa López-Collada Márquez,[7] is the Mexican daughter of a Spanish father from Villaviciosa, Asturias, Spain and a Mexican mother[6][8][9][10] and was his father's secretary.[7][9] Richardson's father was born in Nicaragua.[7] Just before Richardson was born, his father sent his mother to California to give birth because, as Richardson explained, "My father had a complex about not having been born in the United States."[7] Richardson, a U.S. citizen by birthright, was raised during his childhood in Mexico City.[7][9] He was raised Roman Catholic.[11] When Richardson was 13, his parents sent him to Massachusetts to attend a preparatory school, Middlesex School in Concord, Massachusetts, where he played baseball as a pitcher.[7] He entered Tufts University[6][12] in 1966 where he continued to play baseball.[13]

Richardson's original biographies stated he had been drafted by the Kansas City Athletics and the Chicago Cubs to play professional baseball, but a 2005 Albuquerque Journal investigation revealed that he never was on any official draft. Richardson acknowledged the error which he claimed was unintentional, saying that he had been scouted by several teams and told that he "would or could" be drafted, but was mistaken in saying that he was actually drafted.[14]

In 1967, he pitched in the amateur Cape Cod Baseball League for the Cotuit Kettleers in Cotuit, Massachusetts. A Kettleers program included the words "Drafted by K.C." The information which, according to the investigation, was generally provided by the players or their college coaches. Richardson said:

When I saw that program in 1967, I was convinced I was drafted...And it stayed with me all these years.[15]

He earned a Bachelor's degree at Tufts University in 1970, majoring in French and political science and became a president and brother of Delta Tau Delta fraternity. He went on to earn a master's degree in international affairs from Tufts University Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy in 1971. While still in high school, he met his future wife, Barbara Flavin.

Early political career

After college, Richardson worked for Republican Congressman F. Bradford Morse from Massachusetts. He was later a staff member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Richardson worked on congressional relations for the Henry Kissinger State Department during the Nixon Administration.

U.S. Representative

In 1978, Richardson moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico and ran for the House of Representatives in 1980 as a Democrat, losing narrowly to longtime 1st District representative and future United States Secretary of the Interior Manuel Lujan (R). Two years later, Richardson was elected to New Mexico's newly created third district, taking in most of the northern part of the state. Richardson spent a little more than 14 years in Congress, during which time he represented the country's most diverse district and held 2,000 town meetings.[9]

Richardson served as Chairman of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus in the 98th Congress (1983–1985) and as Chairman of the House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Native American Affairs in the 103rd Congress (1993–1994). While in the House, Richardson sponsored bills, including the American Indian Religious Freedom Act Amendments, the Indian Dams Safety Act, the Tribal Self-Governance Act, and the Jicarilla Apache Tribe Water Rights Settlement Act.

He became a member of the Democratic leadership as a deputy majority whip, where he befriended Bill Clinton after they worked closely on several issues, including serving as the ranking House Democrat in favor of NAFTA's passage in 1993,[9] Clinton in turn sent Richardson on various foreign policy missions, including a trip in 1996 in which Richardson traveled to Baghdad with Peter Bourne and engaged in lengthy one-on-one negotiations with Saddam Hussein to secure the release of two American aerospace workers who had been captured by the Iraqis after wandering over the Kuwaiti border. Richardson also visited Nicaragua, Guatemala, Cuba, Peru, India, North Korea, Bangladesh, Nigeria, and Sudan to represent U.S. interests and met with Slobodan Milosevic.[9] In 1996, he played a major role in securing the release of American Evan Hunziker from North Korean custody[16] and for securing a pardon for Eliadah McCord, an American convicted and imprisoned in Bangladesh.[17] Due to these missions, Richardson was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize three times.[9]

Ambassador to the United Nations

As U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations between 1997 and 1998, Richardson flew to Afghanistan and met with the Taliban and with Abdul Rachid Dostum, an Uzbek warlord, but the ceasefire he believed he had negotiated with the help of Bruce Riedel of the National Security Council failed to hold.[18]

U.S. Secretary of Energy

The Senate confirmed Richardson to be Clinton's Secretary of Energy on July 31, 1998. His tenure at the Department of Energy was marred by the Wen Ho Lee nuclear espionage scandal. Richardson publicly named Lee, an employee at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, as a suspect who might have given nuclear secrets to the Chinese government. Lee was later cleared of espionage charges and won a settlement against the federal government for the accusation.[19] Richardson was also criticized by the Senate for his handling of the espionage inquiry, which involved missing hard drives with sensitive data, by not testifying in front of Congress sooner. Richardson justified his response by saying that he was waiting to uncover more information before speaking to Congress.[20] Republican Senators called for Richardson's resignation while both parties criticized his role in the incident, and the scandal ended Richardson's hope of being named as Al Gore's running mate for the 2000 presidential election.[9]

Richardson tightened security following the scandal, and became the first Energy Secretary to implement a plan to dispose of nuclear waste.[citation needed] He created the Director for Native American Affairs position in the Department in 1998, and in January 2000 oversaw the largest return of federal lands, 84,000 acres (340 km²), to an Indian Tribe (the Northern Ute Tribe of Utah) in more than 100 years.[21] Richardson also directed the overhaul of the Department's consultation policy with Native American tribes and established the Tribal Energy Program.

Educational and corporate positions

With the end of the Clinton administration in January 2001, Richardson took on a number of different positions. He was an adjunct professor at Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government and a lecturer at the Armand Hammer United World College of the American West.[22] In 2000, Bill Richardson was awarded a United States Institute of Peace Senior Fellowship. He spent the next year researching and writing on the negotiations with North Korea and the energy dimensions of U.S. relations. In 2011, Richardson was named a senior fellow at the Baker Institute of Rice University.

Richardson also joined Kissinger McLarty Associates, a "strategic advisory firm" headed by former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and former Clinton White House chief of staff Mack McLarty, as Senior Managing Director.[23] From February 2001 to June 2002, he served on the board of directors of Peregrine Systems, Inc. He also served on the corporate boards of several energy companies, including Valero Energy Corporation and Diamond Offshore Drilling. He withdrew from these boards after being nominated by the Democratic Party for governor of New Mexico, but retained considerable stock holdings in Valero and Diamond Offshore.[24] He would later sell these stocks during his campaign for President in 2007, saying he was "getting questions" about the propriety of these holdings, especially given his past as energy secretary, and that it had become a distraction.[25]

Governor of New Mexico

First term

Richardson was elected governor of New Mexico in November 2002, having defeated the Republican candidate, John Sanchez, 56–39%. During the campaign, he set a Guinness World Record for most handshakes in eight hours by a politician, breaking Theodore Roosevelt's record.[26] He succeeded a two-term Republican governor, Gary Johnson. He took office in January 2003 as the only Hispanic Governor in the United States. In his first year, Richardson proposed "tax cuts to promote growth and investment" and passed a broad personal income tax cut and won a statewide special election to transfer money from the state's Permanent Fund to meet current expenses and projects. In early 2005, Richardson helped make New Mexico the first state in the nation to provide $400,000 in life insurance coverage for New Mexico National Guard members who serve on active duty. Thirty-five states have since followed suit.

Working with the legislature, he formed Governor Richardson's Investment Partnership (GRIP) in 2003. The partnership has been used to fund large-scale public infrastructure projects throughout New Mexico, including the use of highway fund to construct a brand new commuter rail line (the Rail Runner) that runs between Belen, Albuquerque, and Bernalillo. He supported a variety LGBT rights in his career as governor; he added sexual orientation and gender identity to New Mexico's list of civil rights categories. He however was opposed to same sex marriage and faced criticism for his use of an anti-gay slur on the Don Imus Show.[27] During the summer of 2003, he met with a delegation from North Korea at their request to discuss concerns over that country's nuclear weapons. At the request of the White House, he also flew to North Korea in 2005, and met with another North Korean delegation in 2006. On December 7, 2006, Richardson was named as the Special Envoy for Hemispheric Affairs for the Secretary General of the Organization of American States with the mandate to "promote dialogue on issues of importance to the region, such as immigration and free trade."[28]

In 2003, Richardson backed and signed legislation creating a permit system for New Mexicans to carry concealed handguns. He applied for and received a concealed weapons permit, though by his own admission he seldom carries a gun.[29]

As Richardson discussed frequently during his 2008 run for President, he supported a controversial New Mexico law allowing illegal immigrants to obtain driver's licenses for reasons of public safety. He said that because of the program, traffic fatalities had gone down, and the percentage of uninsured drivers decreased 33% to 11%.[30]

He was named Chairman of the Democratic Governors Association in 2004 and announced a desire to increase the role of Democratic governors in deciding the future of their party.

In December 2005, Richardson announced the intention of New Mexico to collaborate with billionaire Richard Branson to bring space tourism to the proposed Spaceport America located near Las Cruces, New Mexico. In 2006, Forbes credited Richardson's reforms in naming Albuquerque, New Mexico the best city in the U.S. for business and careers. The Cato Institute, meanwhile, has consistently rated Richardson as one of the most fiscally responsible Democratic governors in the nation.

In March 2006, Richardson vetoed legislation that would ban the use of eminent domain to transfer property to private developers, as allowed by the Supreme Court's 2005 decision in Kelo v. City of New London.[31] He promised to work with the legislature to draft new legislation addressing the issue in the 2007 legislative session.

On September 7, 2006, Richardson flew to Sudan to meet Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir and successfully negotiated the release of imprisoned journalist Paul Salopek. The Sudanese had charged Salopek with espionage on August 26, 2006, while on a National Geographic assignment. In January 2007, at the request of the Save Darfur Coalition, he brokered a 60-day cease-fire between al-Bashir and leaders of several rebel factions in Darfur, the western Sudanese region. The cease-fire never became effective, however, with allegations of breaches on all sides.[32]

Second term

Richardson won his second term as Governor of New Mexico on November 7, 2006, 68–32% against former New Mexico Republican Party Chairman John Dendahl. Richardson received the highest percentage of votes in any gubernatorial election in the state's history.[33]

In December 2006, Richardson announced that he would support a ban on cockfighting in New Mexico.[34] On March 12, 2007, Richardson signed into law a bill that banned cockfighting in New Mexico. Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands are now the only parts of the United States where cockfighting is legal.[35]

During New Mexico's 2007 legislative session, Richardson signed a bill into law that made New Mexico the 12th state to legalize marijuana for medical reasons. When asked if this would hurt him in a Presidential election, he stated that it did not matter, as it was "the right thing to do."[36]

During 2008 and 2009, Richardson faced "possible legal issues" while a federal grand jury investigated pay-to-play allegations in the awarding of a lucrative state contract to a company that gave campaign contributions to Richardson's political action committee, Moving America Forward.[37][38][39] The company in question, CDR, was alleged to have funneled more than $100,000 in donations to Richardson's PAC in exchange for state construction projects.[40] Richardson said when he withdraw his Commerce Secretary nomination that he was innocent; his popularity then slipped below 50% in his home state.[40] In August 2009, federal prosecutors dropped the pending investigation against the governor, and there has been speculation in the media about Richardson's career after his second term as New Mexico governor concludes.[5]

On March 18, 2009, Governor Richardson's office confirmed that he had signed a bill repealing the death penalty,[41] making New Mexico the second U.S. state (after New Jersey) to repeal the death penalty by legislative means since the 1960s. Richardson was subsequently honored with the 2009 Human Rights Award by Death Penalty Focus.[citation needed]

In its April 2010 report, ethics watchdog group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington named Richardson one of 11 worst governors in the United States because of various ethics issues throughout Richardson's term as governor.[42][43][44] The group accused Richardson of allowing political allies to benefit from firms connected to state investments, rewarding close associates with state positions or benefits (including providing a longtime friend and political supporter with a costly state contract), and allowing pay-to-play activity in his administration. They also opined that he fell short on efforts to make state government more transparent.[45]

In December 2010, while still serving as governor, Richardson returned to North Korea in an unofficial capacity at the invitation of the North's chief nuclear negotiator Kim Kye Gwan. Upon arriving in Pyongyang on December 16, Richardson told reporters that his "objective is to see if we can reduce the tension on the Korean peninsula, that is my objective. I am going to have a whole series of talks with North Korean officials here and I look forward to my discussions," he said.[46] On December 19, Richardson said his talks with North Korean officials made "some progress" in trying to resolve what he calls a "very tense" situation. Speaking from Pyongyang, Richardson told U.S. television network CNN that a North Korean general he met was receptive to his proposal for setting up a hotline between North and South Korean forces, and also was open to his idea for a military commission to monitor disputes in and around the Yellow Sea.[47]

After his return from North Korea, Richardson dealt with the issue of a pardon for William H. Bonney, aka Billy the Kid, for killing Sheriff William J. Brady of Lincoln County, New Mexico some 130 years ago. Following up on the promise of a pardon at the time by then-territorial governor Lew Wallace, Richardson said he could not pardon Bonney posthumously because he did not want to second-guess his predecessor's decision. "It was a very close call," Richardson said. "The romanticism appealed to me to issue a pardon, but the facts and the evidence did not support it."[48]

Richardson's second term in office ended in 2011 and he was term-limited from further terms as governor.[49]

2008 presidential campaign

Richardson was a candidate for the Democratic nomination for the 2008 presidential election but dropped out on January 10, 2008 after lackluster showings in the first primary and caucus contests. Despite his long history and friendship with the Clinton family, Richardson endorsed Barack Obama for the Democratic nomination on March 21, 2008, instead of Hillary Clinton.[50] Commentator and Clinton ally James Carville famously compared Richardson to Judas Iscariot for the move.[51] Richardson responded in a Washington Post article, feeling "compelled to defend [himself] against character assassination and baseless allegations."[52]

Richardson was a rumored Vice Presidential candidate for Senator and Democratic presumptive nominee Barack Obama and was fully vetted by the Obama campaign,[53] before Obama chose Joe Biden on August 23, 2008.[54]

Secretary of Commerce nomination

Following Barack Obama's victory in the 2008 presidential election, Richardson's name was frequently mentioned as a possible Cabinet appointment in the incoming Obama administration. Most of this speculation surrounded the position of Secretary of State, given Richardson's background as a diplomat.[55] Richardson did not publicly comment on the speculation.[56]

It was widely reported, and eventually officially announced, that Hillary Clinton was Obama's nominee for Secretary of State. Around this time, it was reported that Richardson was being strongly considered for the position of Commerce Secretary. On December 3, 2008, Obama tapped Richardson for the post.[57]

On January 4, 2009, Richardson withdrew his name as Commerce Secretary nominee because of the federal grand jury investigation into pay-to-play allegations.[58] The New York Times had reported in late December that the grand jury investigation issue would be raised at Richardson's confirmation hearings.[38] Later, in August 2009, Justice Department officials decided not to seek indictments.[59]

Allegations of corruption

During the 2012 trial United States of America v. Carollo, Goldberg and Grimm, the former CPR employee Doug Goldberg described how he was involved in giving Bill Richardson campaign contributions amounting to $100,000 in exchange for his company CPR being hired to handle a $400 million swap deal for the New Mexico state government. During his testimony, Doug Goldberg stated that he had been given an envelope containing a check for $25,000 payable to Moving America Forward, Bill Richardson's political action committee, by his boss Stewart Wolmark and told to deliver it to Bill Richardson at a fund raiser. When Goldberg handed the envelope to Richardson, he allegedly told Goldberg to "Tell the big guy [Steward Wolmark] I'm going to hire you guys". Goldberg went on to testify that CPR was hired but that he later learned that another firm was hired by Richardson to perform the actual work required and that Steward Wolmark had given Richardson a further $75,000 in contributions.[60]

Post-gubernatorial career

In 2011, Richardson joined the boards of APCO Worldwide company Global Political Strategies as chairman,[61] the World Resources Institute,[62] the National Council for Science and the Environment,[63] the National Institute for Civil Discourse at the University of Arizona,[64] and Abengoa (international advisory board).[65] He was also appointed as a special envoy for the Organization of American States.[66]

In 2012, Richardson joined the advisory board of Grow Energy, a startup company founded by young entrepreneurs from Redondo Beach, California, which is utilizing algae as a clean and environmentally-beneficial electricity resource.[67]

Publications

Richardson is credited with having written two books:

- Between Worlds: The Making of an American Life, an autobiography, published March 2007 – Ghost Writer, Mike Ruby, former executive editor and editor for the U.S. News & World Report. [citation needed]

- Leading by Example: How We Can Inspire an Energy and Security Revolution, released October 2007

Articles:

- Universal Transparency: A Goal for the U.S. at the 2012 Nuclear Security Summit, published January 2011, Arms Control Today -Bill Richardson with Gay Dillingham, Charles Streeper, and Arjun Makhijani

- Sweeping Up Dirty Bombs, published Fall 2011, Federation of American Scientists -Bill Richardson, Charles Streeper, and Margarita Sevcik

See also

References

- ^ Crowley, Candy (December 3, 2008). "Obama nominates Richardson for Cabinet". CNN. Archived from the original on December 16 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Richardson withdraws as Commerce nominee". msnbc.msn.com.

- ^ "Bill Richardson bows out of commerce secretary job". CNN. January 5, 2009.

- ^ "Bill Richardson Withdraws as Commerce Secretary-Designate". Fox News. January 4, 2009.

- ^ a b McKinley, James (September 11, 2009). "Gov. Richardson's Future Is Again Talk of Santa Fe". The New York Times. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "Obama Taps Bill Richardson For Commerce". CBS News. December 2, 2008. Archived from the original on December 29 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Joel Achenbach (May 27, 2007). "The Pro-Familia Candidate". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ "The Ancestry of Bill Richardson".

- ^ a b c d e f g h Plotz, David (June 23, 2000). "Energy Secretary Bill Richardson". Slate.com. Archived from the original on October 06 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "slate" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "Illinois Governor Blagojevich Busted on Corruption Charges; Bailout for Detroit; Border Drug Wars". Lou Dobbs Tonight. CNN. December 9, 2008. Archived from the original on December 15 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fairchild, Mary. "Presidential Candidate Bill Richardson". About.com. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

I feel that through my Roman Catholic beliefs...

- ^ "Tufts Alum Chosen to join the Obama cabinet". dca.tufts.edu. December 4, 2008. Archived from the original on December 06 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Bill Richardson, Tufts baseball player, ca. 1969". dca.tufts.edu. December 4, 2008. Archived from the original on December 06 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Richardson backs off baseball claim". The Washington Post. Associated Press. November 25, 2005. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ "Four decades later, Richardson acknowledges he wasn't drafted by pro baseball team". Associated Press. November 24, 2005.

- ^ Egan, Timothy (December 19, 1996). "Man Once Held as a Spy In North Korea Is a Suicide". The New York Times. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ Press, Associated (July 31, 1996). "Houston woman freed from Bangladesh prison — she served 4 years on heroin smuggling conviction". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ Dexter Filkins, The Forever War (New York: Vintage Books/Random House, 2009; orig. ed. 2008), pp. 35–37.

- ^ Mears, Bill (May 22, 2006). "Deal in Wen Ho Lee case may be imminent". CNN. Archived from the original on December 18 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Christopher McCaleb, Ian (June 21, 2000). "Richardson says FBI has determined drives did not leave Los Alamos". CNN.

- ^ "CNN staffs and wire reports – U.S. land transfer to Utah tribe would be largest in 100 years". CNN. January 14, 2000.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) [dead link] - ^ Nedra Pickler (May 22, 2007). "Richardson declares presidential campaign". The Denver Post.

- ^ "Fundación Consejo España-EEUU Bio" (in Spanish).

- ^ Nat Worden (June 11, 2007). "Big Oil Ties Could Muck Up Richardson's Bid". TheStreet.com.

- ^ Associated Press "Bill Richardson Sells Stock in Valero Energy Corp. Amid Questions". Fox News. June 1, 2007.

- ^ Mears, Bill (September 16, 2002). "A Whole Lotta Shaking". Tufts University. Archived from the original on December 10 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Karen Ocamb, and Chris Crain (07/10/2007). "Richardson sorry for 'maricón' moment".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Press Releases".

- ^ "Richardson stands out as pro-gun Democrat". Concord Monitor. 2008.

- ^ "Bill Richardson on Immigration". ontheissues.org. November 15, 2007.

- ^ "Governor vetoes eminent domain legislation". The Santa Fe New Mexican. March 8, 2006.[dead link]

- ^ Polgreen, Lydia (January 11, 2007.). "U.S. Governor Brokers Truce For Darfur". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Council Members: Governor Bill Richardson". New Mexico State Investment Council. See also New Mexico gubernatorial election, 2006.

- ^ "Governor will support a ban on cockfighting". The Santa Fe New Mexican. December 27, 2006.

- ^ "Cockfighting outlawed". KRQE News. 13, March 12, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Blumenthal, Ralph (April 5, 2007). "New Mexico Bars Drug Charge When Overdose Is Reported". The New York Times. Retrieved November 24, 2010.

The governor lobbied strongly for the medical marijuana bill, which he said could hurt his presidential prospects but was "the right thing to do."

- ^ "Cabinet choices touch off scramble in states" (Document).

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ a b Frosch, Dan; McKinley Jr, James C. (December 19, 2008). "Political Donor's Contracts Under Inquiry in New Mexico" (Document).

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Grand Jury Probes Richardson Donor's New Mexico Financing Fee" (Document). Bloomberg News.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Bill Richardson tarnished by scandal" (Document). Politico.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Baker, Deborah (March 18, 2009). "US governor signs measure to abolish death penalty". The Seattle Times.

- ^ "America's Worst Governors". 1400 Eye Street NW • Suite 450 • Washington, DC 20005: Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington. April 21, 2010. Archived from the original on December 31 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Vogel, Ed (April 21, 2010). "Gibbons named on list of worst governors". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on April 24 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Scandals Land Gibbons On 'Worst Governors' List". KVVU-TV (Fox 5, Las Vegas). April 21, 2010. Archived from the original on April 23 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Crew's Worst Governors". Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington. Archived from the original on April 24 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "US governor visits North Korea". Aljazeera. December 16, 2010. Archived from the original on December 17 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "UN Security Council in Emergency Talks on Korean Tensions". Voice of America. December 19, 2010. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- ^ Gast, Phil (December 31, 2010). "No pardon for Billy the Kid". CNN. Retrieved 12-31-2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Constitutional and statutory provisions for number of consecutive terms of elected state officials" (Document). National Governors Association.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|archivedate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|archiveurl=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ "Richardson: 'I am very loyal to the Clintons'". CNN. March 23, 2008. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ Nagourney, Adam (March 22, 2008). "First a Tense Talk With Clinton, Then Richardson Backs Obama". The New York Times. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ Bill Richardson (April 1, 2008). "Loyalty to My Country". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ NYTimes story about vetting process. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ^ CNN story about 20 possible veep nominees. Retrieved August 21, 2008.

- ^ "Bill Richardson: Obama's Secretary Of State?". Huffington Post. November 5, 2008. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ "Richardson mum on job interview". Firstread.msnbc.msn.com. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ "Obama to nominate Richardson for Cabinet". CNN. December 2, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Richardson to withdraw as Commerce secretary. MSNBC, January 4, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2009

- ^ Herzenberg, Michael (August 26, 2009). "No 'pay-to-play' indictment for Gov". News 13. Albuquerque, New Mexico: LIN TV Corporation. KRQE. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

The U.S. Department of Justice has decided not to seek criminal indictments against Gov. Bill Richardson or former high-ranking members of his administration

- ^ Matt Taibbi (June 21, 2012). "The Scam Wall Street Learned From the Mafia". Rolling Stone.

- ^ APCO Worldwide (2011). Former New Mexico Governor, Energy Secretary Bill Richardson joins APCO. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ World Resources Institute (2011). Former Governor Bill Richardson Joins WRI's Board of Directors. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ NCSE (2011). Former Governor Bill Richardson Elected to NCSE Board of Directors. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ National Institute for Civil Discourse (2011). Governor Bill Richardson. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ Abengoa (2011). Bill Richardson, former Governor of New Mexico, joins Abengoa’s International Advisory Board. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ Huffington Post (2011). Richardson named envoy for Org. of American States. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ Grow Energy, Inc. [1]. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

Further sources

- Brooke, James (December 14, 1996). "Traveling Troubleshooter Is Ready to Settle Down, at the U.N.: THE SECOND TERM: The New Lineup William Blaine Richardson". The New York Times, pp. 11.

- Rankin, Adam (July 10, 2005). "Richardson Named As Likely Source of Wen Ho Lee Leak". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved on 2007-03-01.

External links

- 1947 births

- American memoirists

- American people of English descent

- American people of Spanish descent

- American people of Asturian descent

- American political writers

- American politicians of Mexican descent

- American Roman Catholics

- American writers of Mexican descent

- Clinton Administration cabinet members

- Democratic Party state governors of the United States

- Governors of New Mexico

- Hispanic and Latino American governors

- Hispanic and Latino American people in the United States Congress

- John F. Kennedy School of Government faculty

- Living people

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from New Mexico

- New Mexico Democrats

- People from Pasadena, California

- People from Santa Fe, New Mexico

- Permanent Representatives of the United States to the United Nations

- Presidents of the United Nations Security Council

- Rejected or withdrawn nominees to the United States Executive Cabinet

- Tufts Jumbos baseball players

- Tufts University alumni

- United States presidential candidates, 2008

- United States Secretaries of Energy