Amazing Grace: Difference between revisions

Gandydancer (talk | contribs) Undid revision 537903189 by TrollishTackyBling (talk Talk page please ) |

→John Newton's conversion: "took whomever he chose" is a very lame romantic euphemism for the rape being described |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

According to the ''Dictionary of American Hymnology,'' "Amazing Grace" is [[John Newton]]'s spiritual autobiography in verse.<ref name="dah">[http://www.hymnary.org/text/amazing_grace_how_sweet_the_sound Amazing Grace How Sweet the Sound], ''Dictionary of American Hymnology''. Retrieved on October 31, 2009.</ref> In 1725, Newton was born in [[Wapping]], a district in London near the [[Thames]]. His father was a shipping merchant who was brought up as a [[Catholic Church|Catholic]] but had [[Protestantism|Protestant]] sympathies, and his mother was a devout Independent unaffiliated with the [[Anglican Church]]. She had intended Newton to become a clergyman, but she died of [[tuberculosis]] when he was six years old.<ref>Martin (1950), pp. 8–9.</ref> For the next few years, Newton was raised by his emotionally distant stepmother while his father was at sea, and spent some time at a boarding school where he was mistreated.<ref>Newton (1824), p. 12.</ref> At the age of eleven, he joined his father on a ship as an [[apprentice]]; his seagoing career would be marked by headstrong disobedience.<!-- cite needed --> |

According to the ''Dictionary of American Hymnology,'' "Amazing Grace" is [[John Newton]]'s spiritual autobiography in verse.<ref name="dah">[http://www.hymnary.org/text/amazing_grace_how_sweet_the_sound Amazing Grace How Sweet the Sound], ''Dictionary of American Hymnology''. Retrieved on October 31, 2009.</ref> In 1725, Newton was born in [[Wapping]], a district in London near the [[Thames]]. His father was a shipping merchant who was brought up as a [[Catholic Church|Catholic]] but had [[Protestantism|Protestant]] sympathies, and his mother was a devout Independent unaffiliated with the [[Anglican Church]]. She had intended Newton to become a clergyman, but she died of [[tuberculosis]] when he was six years old.<ref>Martin (1950), pp. 8–9.</ref> For the next few years, Newton was raised by his emotionally distant stepmother while his father was at sea, and spent some time at a boarding school where he was mistreated.<ref>Newton (1824), p. 12.</ref> At the age of eleven, he joined his father on a ship as an [[apprentice]]; his seagoing career would be marked by headstrong disobedience.<!-- cite needed --> |

||

As a youth, Newton began a pattern of coming very close to death, examining his relationship with God, then relapsing into bad habits. As a sailor, he denounced his faith after being influenced by a shipmate who discussed ''Characteristics of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times'', a book by the [[Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury|Third Earl of Shaftesbury]], with him. In a series of letters he later wrote, "Like an unwary sailor who quits his port just before a rising storm, I renounced the hopes and comforts of the [[Gospel]] at the very time when every other comfort was about to fail me."<ref>Newton (1824), pp. 21–22.</ref> His disobedience caused him to be [[Impressment|pressed]] into the Royal Navy, and he took advantage of opportunities to overstay his leave and finally deserted to visit Mary "Polly" Catlett, a family friend with whom he had fallen in love.<ref>Martin (1950), p. 23.</ref> After enduring humiliation for deserting,{{efn|Stripped of his rank, whipped in public, and subjected to the abuses directed to prisoners and other press-ganged men in the Navy, he demonstrated insolence and rebellion during his service for the next few months, remarking that the only reason he did not murder the captain or commit suicide was because he did not want Polly to think badly of him. (Martin [1950], pp. 41–47.)}} he managed to get himself traded to a slave ship where he began a career in slave trading.{{efn|Newton kept a series of detailed journals as a slave trader; these are perhaps the first primary source of the [[Atlantic slave trade]] from the perspective of a merchant (Moyers). Women, naked or nearly so, upon their arrival on ship were claimed by the sailors, and Newton alluded to sexual misbehavior in his writings that has since been interpreted by historians to mean that he, along with other sailors, took whomever he chose. (Martin [1950], pp. 82–85)(Aitken, p. 64.)}} |

As a youth, Newton began a pattern of coming very close to death, examining his relationship with God, then relapsing into bad habits. As a sailor, he denounced his faith after being influenced by a shipmate who discussed ''Characteristics of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times'', a book by the [[Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury|Third Earl of Shaftesbury]], with him. In a series of letters he later wrote, "Like an unwary sailor who quits his port just before a rising storm, I renounced the hopes and comforts of the [[Gospel]] at the very time when every other comfort was about to fail me."<ref>Newton (1824), pp. 21–22.</ref> His disobedience caused him to be [[Impressment|pressed]] into the Royal Navy, and he took advantage of opportunities to overstay his leave and finally deserted to visit Mary "Polly" Catlett, a family friend with whom he had fallen in love.<ref>Martin (1950), p. 23.</ref> After enduring humiliation for deserting,{{efn|Stripped of his rank, whipped in public, and subjected to the abuses directed to prisoners and other press-ganged men in the Navy, he demonstrated insolence and rebellion during his service for the next few months, remarking that the only reason he did not murder the captain or commit suicide was because he did not want Polly to think badly of him. (Martin [1950], pp. 41–47.)}} he managed to get himself traded to a slave ship where he began a career in slave trading.{{efn|Newton kept a series of detailed journals as a slave trader; these are perhaps the first primary source of the [[Atlantic slave trade]] from the perspective of a merchant (Moyers). Women, naked or nearly so, upon their arrival on ship were claimed by the sailors, and Newton alluded to sexual misbehavior in his writings that has since been interpreted by historians to mean that he, along with other sailors, took (and presumably raped) whomever he chose. (Martin [1950], pp. 82–85)(Aitken, p. 64.)}} |

||

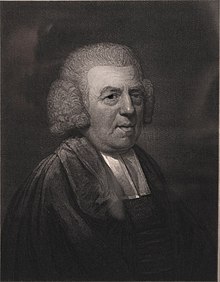

[[File:Newton j.jpg|thumb|left|alt=Engraving of an older heavyset man, wearing robes, vestments, and wig|[[John Newton]] in his later years]] |

[[File:Newton j.jpg|thumb|left|alt=Engraving of an older heavyset man, wearing robes, vestments, and wig|[[John Newton]] in his later years]] |

||

Revision as of 19:58, 13 February 2013

| "Amazing Grace" | |

|---|---|

The bottom of page 53 of Olney Hymns shows the first stanza of the hymn beginning "Amazing Grace!". | |

| Song | |

| Published |

|

| Composer(s) | in Southern Harmony |

| Lyricist(s) | John Newton |

"Amazing Grace" is a Christian hymn with words written by the English poet and clergyman John Newton (1725–1807), published in 1779. Containing a message that forgiveness and redemption are possible regardless of sins committed and that the soul can be delivered from despair through the mercy of God, "Amazing Grace" is one of the most recognizable songs in the English-speaking world.

Newton wrote the words from personal experience. He grew up without any particular religious conviction, but his life's path was formed by a variety of twists and coincidences that were often put into motion by his recalcitrant insubordination. He was pressed (forced into service involuntarily) into the Royal Navy, and after leaving the service became involved in the Atlantic slave trade. In 1748, a violent storm battered his vessel so severely that he called out to God for mercy, a moment that marked his spiritual conversion. However, he continued his slave trading career until 1754 or 1755, when he ended his seafaring altogether and began studying Christian theology.

Ordained in the Church of England in 1764, Newton became curate of Olney, Buckinghamshire, where he began to write hymns with poet William Cowper. "Amazing Grace" was written to illustrate a sermon on New Year's Day of 1773. It is unknown if there was any music accompanying the verses; it may have simply been chanted by the congregation. It debuted in print in 1779 in Newton and Cowper's Olney Hymns, but settled into relative obscurity in England. In the United States however, "Amazing Grace" was used extensively during the Second Great Awakening in the early 19th century. It has been associated with more than 20 melodies, but in 1835 it was joined to a tune named "New Britain" to which it is most frequently sung today.

Author Gilbert Chase writes that "Amazing Grace" is "without a doubt the most famous of all the folk hymns,"[1] and Jonathan Aitken, a Newton biographer, estimates that it is performed about 10 million times annually.[2] It has had particular influence in folk music, and has become an emblematic African American spiritual. Its universal message has been a significant factor in its crossover into secular music. "Amazing Grace" saw a resurgence in popularity in the U.S. during the 1960s and has been recorded thousands of times during and since the 20th century, occasionally appearing on popular music charts.

John Newton's conversion

How industrious is Satan served. I was formerly one of his active undertemptors and had my influence been equal to my wishes I would have carried all the human race with me. A common drunkard or profligate is a petty sinner to what I was.

According to the Dictionary of American Hymnology, "Amazing Grace" is John Newton's spiritual autobiography in verse.[4] In 1725, Newton was born in Wapping, a district in London near the Thames. His father was a shipping merchant who was brought up as a Catholic but had Protestant sympathies, and his mother was a devout Independent unaffiliated with the Anglican Church. She had intended Newton to become a clergyman, but she died of tuberculosis when he was six years old.[5] For the next few years, Newton was raised by his emotionally distant stepmother while his father was at sea, and spent some time at a boarding school where he was mistreated.[6] At the age of eleven, he joined his father on a ship as an apprentice; his seagoing career would be marked by headstrong disobedience.

As a youth, Newton began a pattern of coming very close to death, examining his relationship with God, then relapsing into bad habits. As a sailor, he denounced his faith after being influenced by a shipmate who discussed Characteristics of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times, a book by the Third Earl of Shaftesbury, with him. In a series of letters he later wrote, "Like an unwary sailor who quits his port just before a rising storm, I renounced the hopes and comforts of the Gospel at the very time when every other comfort was about to fail me."[7] His disobedience caused him to be pressed into the Royal Navy, and he took advantage of opportunities to overstay his leave and finally deserted to visit Mary "Polly" Catlett, a family friend with whom he had fallen in love.[8] After enduring humiliation for deserting,[a] he managed to get himself traded to a slave ship where he began a career in slave trading.[b]

Newton often openly mocked the captain by creating obscene poems and songs about him that became so popular the crew began to join in.[9] He entered into disagreements with several colleagues that resulted in his being starved almost to death, imprisoned while at sea and chained like the slaves they carried, then outright enslaved and forced to work on a plantation in Sierra Leone near the Sherbro River. After several months he came to think of Sierra Leone as his home, but his father intervened after Newton sent him a letter describing his circumstances, and a ship found him by coincidence.[c] Newton claimed the only reason he left was because of Polly.[10]

While aboard the ship Greyhound, Newton gained notoriety for being one of the most profane men the captain had ever met. In a culture where sailors commonly used oaths and swore, Newton was admonished several times for not only using the worst words the captain had ever heard, but creating new ones to exceed the limits of verbal debauchery.[11] In March 1748, while the Greyhound was in the North Atlantic, a violent storm came upon the ship that was so rough it swept overboard a crew member who was standing where Newton had been moments before.[d] After hours of the crew emptying water from the ship and expecting to be capsized, Newton and another mate tied themselves to the ship's pump to keep from being washed overboard, working for several hours.[12] After proposing the measure to the captain, Newton had turned and said, "If this will not do, then Lord have mercy upon us!"[13][14] Newton rested briefly before returning to the deck to steer for the next eleven hours. During his time at the wheel he pondered his divine challenge.[12]

About two weeks later, the battered ship and starving crew landed in Lough Swilly, Ireland. For several weeks before the storm, Newton had been reading The Christian's Pattern, a summary of the 15th-century The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis. The memory of the uttered phrase in a moment of desperation did not leave him; he began to ask if he was worthy of God's mercy or in any way redeemable as he had not only neglected his faith but directly opposed it, mocking others who showed theirs, deriding and denouncing God as a myth. He came to believe that God had sent him a profound message and had begun to work through him.[15]

Newton's conversion was not immediate, but he contacted Polly's family and announced his intentions to marry her. Her parents were hesitant as he was known to be unreliable and impetuous. They knew he was profane, but they allowed him to write to Polly, and he set to begin to submit to authority for her sake.[16] He sought a place on a slave ship bound for Africa, and Newton and his crewmates participated in most of the same activities he had written about before; the only action he was able to free himself from was profanity. After a severe illness his resolve was renewed yet he retained the same attitude about slavery as his contemporaries.[e] Newton continued in the slave trade through several voyages where he sailed up rivers in Africa — now as a captain — procured slaves being offered for sale in larger ports, and subsequently transported slaves to North America. In between voyages, he married Polly in 1750 and he found it more difficult to leave her at the beginning of each trip. After three shipping experiences in the slave trade, Newton was promised a position as a captain on a ship with cargo unrelated to slavery, when at thirty years old, he collapsed and never sailed again.[17][f]

Olney curate

Working as a customs agent in Liverpool starting in 1756, Newton began to teach himself Latin, Greek, and theology. He and Polly immersed themselves in the church community, and Newton's passion was so impressive that his friends suggested he become a priest in the Church of England. He was turned down by the Bishop of York in 1758, ostensibly for having no university degree,[18] although the more likely reasons were his leanings toward evangelism and tendency to socialize with Methodists.[19] Newton continued his devotions, and after being encouraged by a friend, he wrote about his experiences in the slave trade and his conversion. The Earl of Dartmouth, impressed with his story, sponsored Newton for ordination with the Bishop of Lincoln, and offered him the curacy of Olney, Buckinghamshire, in 1764.[20]

Olney Hymns

Amazing grace! (how sweet the sound)

That sav'd a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind, but now I see.

'Twas grace that taught my heart to fear,

And grace my fears reliev'd;

How precious did that grace appear

The hour I first believ'd!

Thro' many dangers, toils, and snares,

I have already come;

'Tis grace hath brought me safe thus far,

And grace will lead me home.

The Lord has promis'd good to me,

His word my hope secures;

He will my shield and portion be

As long as life endures.

Yes, when this flesh and heart shall fail,

And mortal life shall cease;

I shall possess, within the veil,

A life of joy and peace.

The earth shall soon dissolve like snow,

The sun forbear to shine;

But God, who call'd me here below,

Will be forever mine.

Olney was a village of about 2,500 residents whose main industry was making lace by hand. The people were mostly illiterate and many of them were poor.[2] Newton's preaching was unique in that he shared many of his own experiences from the pulpit; many clergy preached from a distance, not admitting any intimacy with temptation or sin. He was involved in his parishioners' lives and was much loved, although his writing and delivery were sometimes unpolished.[21] But his devotion and conviction were apparent and forceful, and he often said his mission was to "break a hard heart and to heal a broken heart".[22] He struck a friendship with William Cowper, a gifted writer who had failed at a career in law and suffered bouts of insanity, attempting suicide several times. Cowper enjoyed Olney — and Newton's company; he was also new to Olney and had gone through a spiritual conversion similar to Newton's. Together, their effect on the local congregation was impressive. In 1768, they found it necessary to start a weekly prayer meeting to meet the needs of an increasing number of parishioners. They also began writing lessons for children.[23]

Partly from Cowper's literary influence, and partly because learned vicars were expected to write verses, Newton began to try his hand at hymns, which had become popular through the language, made plain for common people to understand. Several prolific hymn writers were at their most productive in the 18th century, including Isaac Watts — whose hymns Newton had grown up hearing[24] — and Charles Wesley, with whom Newton was familiar. Wesley's brother John, the eventual founder of the Methodist Church, had encouraged Newton to go into the clergy.[g] Watts was a pioneer in English hymn writing, basing his work the Psalms. The most prevalent hymns by Watts and others were written in the common meter in 8.6.8.6: the first line is eight syllables and the second is six.[25]

Newton and Cowper attempted to present a poem or hymn for each prayer meeting. The lyrics to "Amazing Grace" were written in late 1772 and probably used in a prayer meeting for the first time on January 1, 1773.[25] A collection of the poems Newton and Cowper had written for use in services at Olney was bound and published anonymously in 1779 under the title Olney Hymns. Newton contributed 280 of the 348 texts in Olney Hymns; "1 Chronicles 17:16–17, Faith's Review and Expectation" was the title of the poem with the first line "Amazing grace! (how sweet the sound)".[4]

Critical analysis

The general impact of Olney Hymns was immediate and it became a widely popular tool for evangelicals in Britain for many years. Scholars appreciated Cowper's poetry somewhat more than Newton's plaintive and plain language driven from his forceful personality. The most prevalent themes in the verses written by Newton in Olney Hymns are faith in salvation, wonder at God's grace, his love for Jesus, and his ebullient exclamations of the joy he found in his faith.[26] As a reflection of Newton's connection to his parishioners, he wrote many of the hymns in first person, admitting his own experience with sin. Bruce Hindmarsh in Sing Them Over Again To Me: Hymns and Hymnbooks in America considers "Amazing Grace" an excellent example of Newton's testimonial style afforded by the use of this perspective.[27] Several of Newton's hymns were recognized as great work ("Amazing Grace" was not among them) while others seem to have been included to fill in when Cowper was unable to write.[28] Jonathan Aitken calls Newton, specifically referring to "Amazing Grace", an "unashamedly middlebrow lyricist writing for a lowbrow congregation", noting that only twenty-one of the words used in all six verses have more than one syllable.[29]

William Phipps in the Anglican Theological Review and author James Basker have interpreted the first stanza of "Amazing Grace" as evidence of Newton's realization that his participation in the slave trade was his wretchedness, perhaps representing a wider common understanding of Newton's motivations.[30][31] Newton joined forces with a young man named William Wilberforce, the British Member of Parliament who led the Parliamentarian campaign to abolish the slave trade in the British Empire, culminating in the Slave Trade Act 1807. However, Newton became an ardent and outspoken abolitionist after he left Olney in the 1780s; he never connected the construction of the hymn that became "Amazing Grace" to anti-slavery sentiments.[32] The lyrics in Olney Hymns were arranged by their association to the Biblical verses that would be used by Newton and Cowper in their prayer meetings and did not address any political objective. For Newton, the beginning of the year was a time to reflect on one's spiritual progress. At the same time he completed a diary — which has since been lost — that he had begun 17 years before, two years after he quit sailing. The last entry of 1772 was a recounting of how much he had changed since then.[33]

And David the king sat before the Lord, and said, "Who am I, O Lord God, and what is mine house, that thou hast brought me hitherto? And yet this was a small thing in thine eyes, O God; for thou hast also spoken of thy servant's house for a great while to come, and hast regarded me according to the estate of a man of high degree, O Lord God.

The title ascribed to the hymn, "1 Chronicles 17:16–17", refers to David's reaction to the prophet Nathan telling him that God intends to maintain his family line forever. Some Christians interpret this as a prediction that Jesus Christ, as a descendant of David, was promised by God as the salvation for all people.[34] Newton's sermon on that January day in 1773 focused on the necessity to express one's gratefulness for God's guidance, that God is involved in the daily lives of Christians though they may not be aware of it, and that patience for deliverance from the daily trials of life is warranted when the glories of eternity await.[35] Newton saw himself a sinner like David who had been chosen, perhaps undeservedly,[36] and was humbled by it. According to Newton, unconverted sinners were "blinded by the god of this world" until "mercy came to us not only undeserved but undesired ... our hearts endeavored to shut him out till he overcame us by the power of his grace."[33]

The New Testament served as the basis for many of the lyrics of "Amazing Grace". The first verse, for example, can be traced to the story of the Prodigal Son. In the Gospel of Luke the father says, "For this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost, and is found". The story of Jesus healing a blind man who tells the Pharisees that he can now see is told in the Gospel of John. Newton used the words "I was blind but now I see" and declared "Oh to grace how great a debtor!" in his letters and diary entries as early as 1752.[37] The effect of the lyrical arrangement, according to Bruce Hindmarsh, allows an instant release of energy in the exclamation "Amazing grace!", to be followed by a qualifying reply in "how sweet the sound". In An Annotated Anthology of Hymns, Newton's use of an expletive at the beginning of his verse is called "crude but effective" in an overall composition that "suggest(s) a forceful, if simple, statement of faith".[36] Grace is recalled three times in the following verse, culminating in Newton's most personal story of his conversion, underscoring the use of his personal testimony with his parishioners.[27]

The sermon preached by Newton was the last of his William Cowper heard in Olney for Cowper's mental instability returned shortly thereafter. Steve Turner, author of Amazing Grace: The Story of America's Most Beloved Song, suggests Newton may have had his friend in mind, employing the themes of assurance and deliverance from despair for Cowper's benefit.[38]

Dissemination

Although it had its roots in England, "Amazing Grace" became an integral part of the Christian tapestry in the United States. More than 60 of Newton and Cowper's hymns were republished in other British hymnals and magazines, but "Amazing Grace" was not, appearing only once in a 1780 hymnal sponsored by the Countess of Huntingdon. Scholar John Julian commented in his 1892 A Dictionary of Hymnology that outside of the United States, the song was unknown and it was "far from being a good example of Newton's finest work".[39][h] Between 1789 and 1799, four variations of Newton's hymn were published in the U.S. in Baptist, Dutch Reformed, and Congregationalist hymnodies;[34] by 1830 Presbyterians and Methodists also included Newton's verses in their hymnals.[40][41]

The greatest influences in the 19th century that propelled "Amazing Grace" to spread across the U.S. and become a staple of religious services in many denominations and regions were the Second Great Awakening and the development of shape note singing communities. A tremendous religious movement swept the U.S. in the early 19th century, marked by the growth and popularity of churches and religious revivals that got their start in Kentucky and Tennessee. Unprecedented gatherings of thousands of people attended camp meetings where they came to experience salvation; preaching was fiery and focused on saving the sinner from temptation and backsliding.[42] Religion was stripped of ornament and ceremony, and made as plain and simple as possible; sermons and songs often used repetition to get across to a rural population of poor and mostly uneducated people the necessity of turning away from sin. Witnessing and testifying became an integral component to these meetings, where a congregation member or even a stranger would rise and recount his turn from a sinful life to one of piety and peace.[40] "Amazing Grace" was one of many hymns that punctuated fervent sermons, although the contemporary style used a refrain, borrowed from other hymns, that employed simplicity and repetition such as:

Amazing grace! How sweet the sound

That saved a wretch like me.

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind but now I see.

Shout, shout for glory,

Shout, shout aloud for glory;

Brother, sister, mourner,

All shout glory hallelujah.[42]

Simultaneously, an unrelated movement of communal singing was established throughout the South and Western states. A format of teaching music to illiterate people appeared in 1800. It used four sounds to symbolize the basic scale: fa-sol-la-fa-sol-la-mi-fa. Each sound was accompanied by a specifically shaped note and thus became known as shape note singing. The method was simple to learn and teach, so schools were established throughout the South and West. Communities would come together for an entire day of singing in a large building where they sat in four distinct areas surrounding an open space, one member directing the group as a whole. Most of the music was Christian, but the purpose of communal singing was not primarily spiritual. Communities either could not afford music accompaniment or rejected it out of a Calvinistic sense of simplicity, so the songs were sung a cappella.[43]

"New Britain" tune

When originally used in Olney, it is unknown what music, if any, accompanied the verses written by John Newton. Contemporary hymnbooks did not contain music and were simply small books of religious poetry. The first known instance of Newton's lines joined to music was in A Companion to the Countess of Huntingdon's Hymns (London, 1808), where it is set to the tune "Hephzibah" by English composer John Jenkins Husband.[44] Common meter hymns were interchangeable with a variety of tunes; more than twenty musical settings of "Amazing Grace" circulated with varying popularity until 1835 when William Walker assigned Newton's words to a traditional song named "New Britain", which was itself an amalgamation of two melodies ("Gallaher" and "St. Mary") first published in the Columbian Harmony by Charles H. Spilman and Benjamin Shaw (Cincinnati, 1829). Spilman and Shaw, both students at Kentucky's Centre College, compiled their tunebook both for public worship and revivals, to satisfy "the wants of the Church in her triumphal march." Most of the tunes had been previously published, but "Gallaher" and "St. Mary" had not.[45] As neither tune is attributed and both show elements of oral transmission, scholars can only speculate that they are possibly of British origin.[46]

"Amazing Grace", with the words written by Newton and joined with "New Britain", the melody most currently associated with it, appeared for the first time in Walker's shape note tunebook Southern Harmony in 1847.[47] It was, according to author Steve Turner, a "marriage made in heaven ... The music behind 'amazing' had a sense of awe to it. The music behind 'grace' sounded graceful. There was a rise at the point of confession, as though the author was stepping out into the open and making a bold declaration, but a corresponding fall when admitting his blindness."[48] Walker's collection was enormously popular, selling about 600,000 copies all over the U.S. when the total population was just over 20 million. Another shape note tunebook named The Sacred Harp (1844) by Georgia residents Benjamin Franklin White and Elisha J. King became widely influential and continues to be used.[49]

Another verse was first recorded in Harriet Beecher Stowe's immensely influential 1852 anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. Three verses were emblematically sung by Tom in his hour of deepest crisis.[50] He sings the sixth and fifth verses in that order, and Stowe included another verse not written by Newton that had been passed down orally in African American communities for at least 50 years. It was originally one of between 50 to 70 verses of a song titled "Jerusalem, My Happy Home" that first appeared in a 1790 book called A Collection of Sacred Ballads:

"Amazing Grace" came to be an emblem of a Christian movement and a symbol of the U.S. itself as the country was involved in a great political experiment, attempting to employ democracy as a means of government. Shape note singing communities, with all the members sitting around an open center, each song employing a different director, illustrated this in practice. Simultaneously, the U.S. began to expand westward into previously unexplored territory that was often wilderness. The "dangers, toils, and snares" of Newton's lyrics had both literal and figurative meanings for Americans.[49] This became poignantly true during the most serious test of American cohesion in the U.S. Civil War (1861–1865). "Amazing Grace" set to "New Britain" was included in two hymnals distributed to soldiers and with death so real and imminent, religious services in the military became commonplace.[53] The hymn was translated into other languages as well: while on the Trail of Tears, the Cherokee sang Christian hymns as a way of coping with the ongoing tragedy, and a version of the song by Samuel Worcester that had been translated into the Cherokee language became very popular.[54][55]

Urban revival

Although "Amazing Grace" set to "New Britain" was popular, other versions existed regionally. Primitive Baptists in the Appalachian region often used "New Britain" with other hymns, and sometimes sing the words of "Amazing Grace" to other folk songs, including titles such as "In the Pines", "Pisgah", "Primrose", and "Evan", as all are able to be sung in common meter, of which the majority of their repertoire consists.[56][57] A tune named "Arlington" accompanied Newton's verses as much as "New Britain" for a time in the late 19th century.

Two musical arrangers named Dwight Moody and Ira Sankey heralded another religious revival in the cities of the U.S. and Europe, giving the song international exposure. Moody's preaching and Sankey's musical gifts were significant; their arrangements were the forerunners of gospel music, and churches all over the U.S. were eager to acquire them.[58] Moody and Sankey began publishing their compositions in 1875, and "Amazing Grace" appeared three times with three different melodies, but they were the first to give it its title; hymns were typically published using the first line of the lyrics, or the name of the tune such as "New Britain". A publisher named Edwin Othello Excell gave the version of "Amazing Grace" set to "New Britain" immense popularity by publishing it in a series of hymnals that were used in urban churches. Excell altered some of Walker's music, making it more contemporary and European, giving "New Britain" some distance from its rural folk-music origins. Excell's version was more palatable for a growing urban middle class and arranged for larger church choirs. Several editions featuring Newton's first three stanzas and the verse previously included by Harriet Beecher Stowe in Uncle Tom's Cabin were published by Excell between 1900 and 1910, and his version of "Amazing Grace" became the standard form of the song in American churches.[59][60]

Recorded versions

With the advent of recorded music and radio, "Amazing Grace" began to cross over from primarily a gospel standard to secular audiences. The ability to record combined with the marketing of records to specific audiences allowed "Amazing Grace" to take on thousands of different forms in the 20th century. Where Edwin Othello Excell sought to make the singing of "Amazing Grace" uniform throughout thousands of churches, records allowed artists to improvise with the words and music specific to each audience. Allmusic lists more than 7,000 recordings—including re-releases and compilations—as of September 2011.[61] Its first recording is an a cappella version from 1922 by the Sacred Harp Choir. It was included from 1926 to 1930 in Okeh Records' catalog, which typically concentrated strongly on blues and jazz. Demand was high for black gospel recordings of the song by H. R. Tomlin and J. M. Gates. A poignant sense of nostalgia accompanied the recordings of several gospel and blues singers in the 1940s and 1950s who used the song to remember their grandparents, traditions, and family roots.[62] It was recorded with musical accompaniment for the first time in 1930 by Fiddlin' John Carson, although to another folk hymn named "At the Cross", not to "New Britain".[63] "Amazing Grace" is emblematic of several kinds of folk music styles, often used as the standard example to illustrate such musical techniques as lining out and call and response, that have been practiced in both black and white folk music.[64]

Those songs come out of conviction and suffering. The worst voices can get through singing them 'cause they're telling their experiences.

Mahalia Jackson's 1947 version received significant radio airplay, and as her popularity grew throughout the 1950s and 1960s, she often sang it at public events such as concerts at Carnegie Hall.[66] Author James Basker states that the song has been employed by African Americans as the "paradigmatic Negro spiritual" because it expresses the joy felt at being delivered from slavery and worldly miseries.[31] Anthony Heilbut, author of The Gospel Sound, states that the "dangers, toils, and snares" of Newton's words are a "universal testimony" of the African American experience.[67] In the 1960s with the African American Civil Rights Movement and opposition to the Vietnam War, the song took on a political tone. Mahalia Jackson employed "Amazing Grace" for Civil Rights marchers, writing that she used it "to give magical protection — a charm to ward off danger, an incantation to the angels of heaven to descend ... I was not sure the magic worked outside the church walls ... in the open air of Mississippi. But I wasn't taking any chances."[68] Folk singer Judy Collins, who knew the song before she could remember learning it, witnessed Fannie Lou Hamer leading marchers in Mississippi in 1964, singing "Amazing Grace". Collins also considered it a talisman of sorts, and saw its equal emotional impact on the marchers, witnesses, and law enforcement who opposed the civil rights demonstrators.[3] According to fellow folk singer Joan Baez, it was one of the most requested songs from her audiences, but she never realized its origin as a hymn; by the time she was singing it in the 1960s she said it had "developed a life of its own".[69] It even made an appearance at the Woodstock Music Festival in 1969 during Arlo Guthrie's performance.[70]

Collins decided to record it in the late 1960s amid an atmosphere of counterculture introspection; she was part of an encounter group that ended a contentious meeting by singing "Amazing Grace" as it was the only song to which all the members knew the words. Her producer was present and suggested she include a version of it on her 1970 album Whales & Nightingales. Collins, who has a history of alcohol abuse, claimed that the song was able to "pull her through" to recovery.[3] It was recorded in St. Paul's, the chapel at Columbia University, chosen for the acoustics. She chose an a cappella arrangement that was close to Edwin Othello Excell's, accompanied by a chorus of amateur singers who were friends of hers. Collins connected it to the Vietnam War, to which she objected: "I didn't know what else to do about the war in Vietnam. I had marched, I had voted, I had gone to jail on political actions and worked for the candidates I believed in. The war was still raging. There was nothing left to do, I thought ... but sing 'Amazing Grace'."[71] Gradually and unexpectedly, the song began to be played on the radio, and then be requested. It rose to number 15 on the Billboard Hot 100, remaining on the charts for 15 weeks,[72] as if, she wrote, her fans had been "waiting to embrace it".[73] In the UK, it charted 8 times between 1970 and 1972, peaking at number 5 and spending a total of 75 weeks on popular music charts.[74]

Although Collins used it as a catharsis for her opposition to the Vietnam War, two years after her rendition, the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards, senior Scottish regiment of the British Army, recorded an instrumental version featuring a bagpipe soloist accompanied by a pipe and drum band. The tempo of their arrangement was slowed to allow for the bagpipes, but it was based on Collins': it began with a bagpipe solo introduction similar to her lone voice, then it was accompanied by the band of bagpipes and horns, whereas in her version she is backed up by a chorus. It hit number 1 in the UK singles chart in April 1972, spending 24 weeks total on the charts, topped the RPM national singles chart in Canada for three weeks,[75] and rose as high as number 11 in the U.S.[76][77] It is also a controversial instrumental, as it combined pipes with a military band. The Pipe Major of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards was summoned to Edinburgh Castle and chastised for demeaning the bagpipes.[78] Funeral processions for killed police, fire, and military personnel have often played a bagpipes version ever since.

Aretha Franklin and Rod Stewart also recorded "Amazing Grace" around the same time, and both of their renditions were popular.[i] All four versions were marketed to distinct types of audiences thereby assuring its place as a pop song.[79] Johnny Cash recorded it on his 1975 album Sings Precious Memories, dedicating it to his older brother Jack, who had been killed in a mill accident when they were boys in Dyess, Arkansas. Cash and his family sang it to themselves while they worked in the cotton fields following Jack's death. Cash often included the song when he toured prisons, saying "For the three minutes that song is going on, everybody is free. It just frees the spirit and frees the person."[3]

The U.S. Library of Congress has a collection of 3,000 versions of and songs inspired by "Amazing Grace", some of which were first-time recordings by folklorists Alan and John Lomax, a father and son team who in 1932 traveled thousands of miles across the South to capture the different regional styles of the song. More contemporary renditions include samples from such popular artists as Sam Cooke and The Soul Stirrers (1963), The Byrds (1970), Elvis Presley (1971), Skeeter Davis (1972), Mighty Clouds of Joy (1972), Amazing Rhythm Aces (1975), Willie Nelson (1976), and The Lemonheads (1992).[63]

Popular use

Somehow, "Amazing Grace" [embraced] core American values without ever sounding triumphant or jingoistic. It was a song that could be sung by young and old, Republican and Democrat, Southern Baptist and Roman Catholic, African American and Native American, high-ranking military officer and anticapitalist campaigner.

Following the appropriation of the hymn in secular music, "Amazing Grace" became such an icon in American culture that it has been used for a variety of secular purposes and marketing campaigns, placing it in danger of becoming a cliché. It has been mass produced on souvenirs, lent its name to a Superman villain, appeared on The Simpsons to demonstrate the redemption of a murderous character named Sideshow Bob, incorporated into Hare Krishna chants and adapted for Wicca ceremonies.[81] The hymn has been employed in several films, including Alice's Restaurant, Coal Miner's Daughter, and Silkwood. It is referenced in the 2006 film Amazing Grace, which highlights Newton's influence on the leading British abolitionist William Wilberforce. The 1982 science fiction film Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan used "Amazing Grace" amid a context of Christian symbolism, to memorialize the death of Mr. Spock[82] but more practically, because the song has become "instantly recognizable to many in the audience as music that sounds appropriate for a funeral" according to a Star Trek scholar.[83] Since 1954 when an organ instrumental of "New Britain" became a bestseller, "Amazing Grace" has been associated with funerals and memorial services.[84] It has become a song that inspires hope in the wake of tragedy, becoming a sort of "spiritual national anthem" according to authors Mary Rourke and Emily Gwathmey.[85]

Modern interpretations

In recent years, the words of the hymn have been changed in some religious publications to downplay a sense of imposed self-loathing by its singers. The second line, "That saved a wretch like me!" has been rewritten as "That saved and strengthened me", "save a soul like me", or "that saved and set me free".[86] Kathleen Norris in her book Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith characterizes this transformation of the original words as "wretched English" making the line that replaces the original "laughably bland".[87] Part of the reason for this change has been the altered interpretations of what wretchedness and grace means. Newton's Calvinistic view of redemption and divine grace formed his perspective that he considered himself a sinner so vile that he was unable to change his life or be redeemed without God's help. Yet his lyrical subtlety, in Steve Turner's opinion, leaves the hymn's meaning open to a variety of Christian and non-Christian interpretations.[88] "Wretch" also represents a period in Newton's life when he saw himself outcast and miserable, as he was when he was enslaved in Sierra Leone; his own arrogance was matched by how far he had fallen in his life.[89]

The communal understanding of redemption and human self-worth has changed since Newton's time. Since the 1970s, self-help books, psychology, and some modern expressions of Christianity have viewed this disparity in terms of grace being an innate quality within all people who must be inspired or strong enough to find it: something to achieve. In contrast to Newton's vision of wretchedness as his willful sin and distance from God, wretchedness has instead come to mean an obstacle of physical, social, or spiritual nature to overcome in order to achieve a state of grace, happiness, or contentment. Since its immense popularity and iconic nature, "grace" and the meaning behind the words of "Amazing Grace" have become as individual as the singer or listener.[90] Bruce Hindmarsh suggests that the secular popularity of "Amazing Grace" is due to the absence of any mention of God in the lyrics until the fourth verse (by Excell's version, the fourth verse begins "When we've been there ten thousand years"), and that the song represents the ability of humanity to transform itself instead of a transformation taking place at the hands of God. "Grace", however, to John Newton had a clearer meaning, as he used the word to represent God or the power of God.[91]

The transformative power of the song was investigated by journalist Bill Moyers in a documentary released in 1990. Moyers was inspired to focus on the song's power after watching a performance at Lincoln Center, where the audience consisted of Christians and non-Christians, and he noticed that it had an equal impact on everybody in attendance, unifying them.[22] James Basker also acknowledged this force when he explained why he chose "Amazing Grace" to represent a collection of anti-slavery poetry: "there is a transformative power that is applicable ... : the transformation of sin and sorrow into grace, of suffering into beauty, of alienation into empathy and connection, of the unspeakable into imaginative literature."[92]

Moyers interviewed Collins, Cash, opera singer Jessye Norman, Appalachian folk musician Jean Ritchie and her family, white Sacred Harp singers in Georgia, black Sacred Harp singers in Alabama, and a prison choir at the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville. Collins, Cash, and Norman were unable to discern if the power of the song came from the music or the lyrics. Norman, who once notably sang it at the end of a large outdoor rock concert for Nelson Mandela's 70th birthday, stated, "I don't know whether it's the text — I don't know whether we're talking about the lyrics when we say that it touches so many people — or whether it's that tune that everybody knows." A prisoner interviewed by Moyers explained his literal interpretation of the second verse: "'Twas grace that taught my heart to fear, and grace my fears relieved" by saying that the fear became immediately real to him when he realized he may never get his life in order, compounded by the loneliness and restriction in prison. Gospel singer Marion Williams summed up its effect: "That's a song that gets to everybody".[3]

The Dictionary of American Hymnology claims it is included in more than a thousand published hymnals, and recommends its use for "occasions of worship when we need to confess with joy that we are saved by God's grace alone; as a hymn of response to forgiveness of sin or as an assurance of pardon; as a confession of faith or after the sermon."[4]

Notes

- ^ Stripped of his rank, whipped in public, and subjected to the abuses directed to prisoners and other press-ganged men in the Navy, he demonstrated insolence and rebellion during his service for the next few months, remarking that the only reason he did not murder the captain or commit suicide was because he did not want Polly to think badly of him. (Martin [1950], pp. 41–47.)

- ^ Newton kept a series of detailed journals as a slave trader; these are perhaps the first primary source of the Atlantic slave trade from the perspective of a merchant (Moyers). Women, naked or nearly so, upon their arrival on ship were claimed by the sailors, and Newton alluded to sexual misbehavior in his writings that has since been interpreted by historians to mean that he, along with other sailors, took (and presumably raped) whomever he chose. (Martin [1950], pp. 82–85)(Aitken, p. 64.)

- ^ Newton's father was friends with Joseph Manesty, who intervened several times in Newton's life. Newton was supposed to go to Jamaica on Manesty's ship, but missed it while he was with the Catletts. When Newton's father got his son's letter detailing his conditions in Sierra Leone, he asked Manesty to find Newton. Manesty sent the Greyhound, which traveled along the African coast trading at various stops. An associate of Newton lit a fire signaling to ships he was interested in trading only 30 minutes before the Greyhound appeared. (Aitken, pp. 34–35, 64–65.)

- ^ Several retellings of Newton's life story claim that he was carrying slaves during the voyage in which he experienced his conversion, but the ship was carrying livestock, wood, and beeswax from the coast of Africa. (Aitken, p. 76.)

- ^ When Newton began his journal in 1750, not only was slave trading seen as a respectable profession by the majority of Britons, its necessity to the overall prosperity of the kingdom was communally understood and approved. Only Quakers, who were much in the minority and perceived as eccentric, had raised any protest about the practice. (Martin and Spurrell [1962], pp. xi–xii.)

- ^ Newton's biographers and Newton himself does not put a name to this episode other than a "fit" in which he became unresponsive, suffering dizziness and a headache. His doctor advised him not to go to sea again, and Newton complied. Jonathan Aitken called it a stroke or seizure, but it is unknown what caused it. (Martin [1950], pp. 140–141.)(Aitken, p. 125.)

- ^ Watts had previously written a hymn named "Alas! And Did My Saviour Bleed" that contained the lines "Amazing pity! Grace unknown!/ And love beyond degree!". Philip Doddridge, another well-known hymn writer, wrote another in 1755 titled "The Humiliation and Exaltation of God's Israel" that began "Amazing grace of God on high!" and included other similar wording to Newton's verses. Newton biographer Jonathan Aitken states that Watts had inspired most of Newton's compositions. (Turner, pp. 82–83.)(Aitken, pp. 28–29.)

- ^ Only since the 1950s has it gained some popularity in the UK; not until 1964 was it published with the music most commonly associated with it. (Noll and Blumhofer, p. 8)

- ^ Franklin's version is a prime example of "long meter" rendition: she sings several notes representing a syllable and the vocals are more dramatic and lilting. Her version lasts over ten minutes in comparison to the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards' that lasts under three minutes. (Tallmadge)(Turner, pp. 150–151.)

References

- ^ Chase, p. 181.

- ^ a b Aitken, p. 224.

- ^ a b c d e Moyers, Bill (director). Amazing Grace with Bill Moyers, Public Affairs Television, Inc. (1990).

- ^ a b c Amazing Grace How Sweet the Sound, Dictionary of American Hymnology. Retrieved on October 31, 2009.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 8–9.

- ^ Newton (1824), p. 12.

- ^ Newton (1824), pp. 21–22.

- ^ Martin (1950), p. 23.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 51–52.

- ^ Martin (1950), p. 63.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Martin (1950), p. 73.

- ^ Newton (1824), p. 41.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 70–71.

- ^ Aitken, pp. 81–84.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 82–85.

- ^ Aitken, p. 125.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 166–188.

- ^ Aitken, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 198–200.

- ^ Martin (1950), pp. 208–217.

- ^ a b Pollock, John (2009). "Amazing Grace: The great Sea Change in the Life of John Newton", The Trinity Forum Reading, The Trinity Forum.

- ^ Turner, p. 76.

- ^ Aitken, p. 28.

- ^ a b Turner, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Benson, p. 339.

- ^ a b Noll and Blumhofer, p. 6.

- ^ Benson, p. 338.

- ^ Aitken, p. 226.

- ^ Phipps, William (Summer 1990). " 'Amazing Grace' in the hymnwriter's life", Anglican Theological Review, 72 (3), pp. 306–313.

- ^ a b Basker, p. 281.

- ^ Aitken, p. 231.

- ^ a b Aitken, p. 227.

- ^ a b Noll and Blumhofer, p. 8.

- ^ Turner, p. 81.

- ^ a b Watson, p. 215.

- ^ Aitken, p. 228.

- ^ Turner, p. 86.

- ^ Julian, p. 55.

- ^ a b Noll and Blumhofer, p. 10.

- ^ Aitken, pp. 232–233.

- ^ a b Turner, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Turner, p. 117.

- ^ The Hymn Tune Index, Search="Hephzibah". University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana Library website. Retrieved on December 31, 2010.

- ^ Turner, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Turner, p. 123.

- ^ Noll and Blumhofer, p. 11.

- ^ Turner, p. 124.

- ^ a b Turner, p. 126.

- ^ Stowe, p. 417.

- ^ Aitken, p. 235.

- ^ Watson, p. 216.

- ^ Turner, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Duvall, p. 35.

- ^ Swiderski, p. 91.

- ^ Patterson, p. 137.

- ^ Sutton, Brett (January 1982). "Shape-Note Tune Books and Primitive Hymns", Ethnomusicology, 26 (1), pp. 11–26.

- ^ Turner, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Noll and Blumhofer, p. 13.

- ^ Turner, pp. 137–138, 140–145.

- ^ Allmusic search=Amazing Grace Song, Allmusic. Retrieved on September 18, 2011.

- ^ Turner, pp. 154–155.

- ^ a b Amazing Grace: Special Presentation: Amazing Grace Timeline United States Library of Congress Performing Arts Encyclopedia. Retrieved on November 1, 2008.

- ^ Tallmadge, William (May 1961). "Dr. Watts and Mahalia Jackson: The Development, Decline, and Survival of a Folk Style in America", Ethnomusicology, 5 (2), pp. 95–99.

- ^ Turner, p. 157.

- ^ "Mahalia Jackson." Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement 9: 1971–1975. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1994.

- ^ Turner, p. 148.

- ^ Aitken, p. 236.

- ^ Turner, p. 162.

- ^ Turner, p. 175.

- ^ Collins, p. 165.

- ^ Whitburn, p. 144.

- ^ Collins, p. 166.

- ^ Brown, Kutner, and Warwick p. 179.

- ^ Top Singles – Volume 17, No. 17, June 10 1972 RPM Magazine (June 10, 1972). Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- ^ Brown, Kutner, and Warwick p. 757.

- ^ Whitburn, p. 610.

- ^ Turner, p. 188.

- ^ Turner, p. 192.

- ^ Turner, p. 205.

- ^ Turner, pp. 195–205.

- ^ Noll and Blumhofer, p. 15.

- ^ Porter and McLaren, p. 157.

- ^ Turner, p. 159.

- ^ Rourke and Gwathmey, p. 108.

- ^ Saunders, William (2003). Lenten Music Arlington Catholic Herald. Retrieved on February 7, 2010.

- ^ Norris, p. 66.

- ^ Turner, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Bruner and Ware, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Turner, pp. 218–220.

- ^ Noll and Blumhofer, p. 16.

- ^ Basker, p. xxxiv.

Bibliography

- Aitken, Jonathan (2007). John Newton: From Disgrace to Amazing Grace, Crossway Books. ISBN 1-58134-848-7

- Basker, James (2002). Amazing Grace: An Anthology of Poems About Slavery, 1660–1810, Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09172-9

- Benson, Louis (1915). The English Hymn: Its Development and Use in Worship, The Presbyterian Board of Publication, Philadelphia.

- Bradley, Ian (ed.)(1989). The Book of Hymns, The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-346-2

- Brown, Tony; Kutner, Jon; Warwick, Neil (2000). Complete Book of the British Charts: Singles & Albums, Omnibus. ISBN 0-7119-7670-8

- Bruner, Kurt; Ware, Jim (2007). Finding God in the Story of Amazing Grace, Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. ISBN 1-4143-1181-8

- Chase, Gilbert (1987). America's Music, From the Pilgrims to the Present, McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-252-00454-X

- Collins, Judy (1998). Singing Lessons: A Memoir of Love, Loss, Hope, and Healing , Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-02745-X

- Duvall, Deborah (2000). Tahlequah and the Cherokee Nation, Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-0782-2

- Julian, John (ed.)(1892). A Dictionary of Hymnology, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York.

- Martin, Bernard (1950). John Newton: A Biography, William Heineman, Ltd., London.

- Martin, Bernard and Spurrell, Mark, (eds.)(1962). The Journal of a Slave Trader (John Newton), The Epworth Press, London.

- Newton, John (1811). Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade, Samuel Whiting and Co., London.

- Newton, John (1824). The Works of the Rev. John Newton Late Rector of the United Parishes of St. Mary Woolnoth and St. Mary Woolchurch Haw, London: Volume 1, Nathan Whiting, London.

- Noll, Mark A.; Blumhofer, Edith L. (eds.) (2006). Sing Them Over Again to Me: Hymns and Hymnbooks in America, University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-1505-5

- Norris, Kathleen (1999). Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith, Riverhead. ISBN 1-57322-078-7

- Patterson, Beverly Bush (1995). The Sound of the Dove: Singing in Appalachian Primitive Baptist Churches, University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02123-1

- Porter, Jennifer; McLaren, Darcee (eds.)(1999). Star Trek and Sacred Ground: Explorations of Star Trek, Religion, and American Culture, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-585-29190-X

- Rourke, Mary; Gwathmey, Emily (1996). Amazing Grace in America: Our Spiritual National Anthem, Angel City Press. ISBN 1-883318-30-0

- Stowe, Harriet Beecher (1899). Uncle Tom's Cabin, or Life Among the Lowly, R. F. Fenno & Company, New York City.

- Swiderski, Richard (1996). The Metamorphosis of English: Versions of Other Languages, Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-89789-468-5

- Turner, Steve (2002). Amazing Grace: The Story of America's Most Beloved Song, HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-000219-0

- Watson, J. R. (ed.)(2002). An Annotated Anthology of Hymns, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-826973-0

- Whitburn, Joel (2003). Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Singles, 1955–2002, Record Research, Inc. ISBN 0-89820-155-1

External links

- U.S. Library of Congress Amazing Grace collection

- Cowper & Newton Museum in Olney, England

- Amazing Grace: Some Early Tunes Anthology of the American Hymn-Tune Repertory

- Amazing Grace: The story behind the song and its connection to Lough Swilly

- 1772 works

- 1970 singles

- 1971 singles

- 1972 singles

- Billy "Crash" Craddock songs

- British poems

- Christian hymns

- Christian songs

- Elvis Presley songs

- Gospel songs

- Irish Singles Chart number-one singles

- Joan Baez songs

- Judy Collins songs

- Kikki Danielsson songs

- Mormon Tabernacle Choir songs

- Number-one singles in Australia

- Singles certified gold by the Recording Industry Association of Japan

- Susan Boyle songs

- UK Singles Chart number-one singles