Drunken Sailor: Difference between revisions

| Line 309: | Line 309: | ||

*[http://www.musicanet.org/robokopp/shanty/whatshal.htm Example version with lyrics]. |

*[http://www.musicanet.org/robokopp/shanty/whatshal.htm Example version with lyrics]. |

||

*[http://www.scheepspraat.nl/drunken%20sailor.htm Another example version with lyrics and alternative chorus]. |

*[http://www.scheepspraat.nl/drunken%20sailor.htm Another example version with lyrics and alternative chorus]. |

||

* [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DWZ67Hq_jnw |

* [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DWZ67Hq_jnw An example of a high school male choir singing the version arranged by Robert Shaw and Alice Parker]. |

||

[[Category:19th-century songs]] |

[[Category:19th-century songs]] |

||

Revision as of 01:36, 28 February 2013

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2010) |

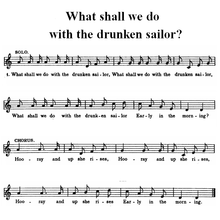

Drunken Sailor is a sea shanty, also known as What Shall We Do with a/the Drunken Sailor?

The shanty was sung to accompany certain work tasks aboard sailing ships, especially those that required a bright walking pace. It is believed to originate in the early 19th century or before, during a period when ships' crews, especially those of military vessels, were sufficiently large to permit hauling a rope whilst simply marching along the deck. With the advent of merchant packet and clipper ships and their smaller crews, which required different working methods, use of the shanty appears to have declined or shifted to other, minor tasks.

"Drunken Sailor" was revived as a popular song among non-sailors in the 20th century, and grew to become one of the best-known songs of the shanty repertoire among mainstream audiences. It has been performed and recorded by many musical artists and appeared in many popular media.

Although the song's lyrics vary, they usually contain some variant of the question, "What shall we do with a drunken sailor, early in the morning?" In some styles of performance, each successive verse suggests a method of sobering or punishing the drunken sailor. In other styles, further questions are asked and answered about different people.

The song is #322 in the Roud Folk Song Index.

Origins

The air of the song, in the Dorian mode and in duple march rhythm, has been compared to the style of a bagpipe melody.[1] The authorship and origin of "Drunken Sailor" are unknown.

History

As a shanty

Although typically conceived as a song originating in British vessels,[citation needed] the evidence describing it in its earliest appearances come from America [citation needed]. The first published description of the shanty[2] is found in an account of an 1839 whaling voyage out of New London, Connecticut to the Pacific Ocean. It was used as an example of a song that was, "performed with very good effect when there is a long line of men hauling together." The tune was noted, along with these lyrics:

- Ho! Ho! and up she rises

- Ho! Ho! and up she rises

- Ho! Ho! and up she rises,

- Early in the morning.[3]

Although this is the earliest discovered published mention, there is some indication that the shanty is at least as old as the 1820s. In Eckstorm and Smyth's collection Minstrelsy of Maine (published 1927), the editors note that one of their grandmothers, who sang the song, claimed to have heard it used during the task of tacking (i.e. "walking away" with braces) on the Penobscot River “probably considerably over a hundred years ago.”[4]

Despite these indications of the song's existence in the first half of the 19th century, references to it are rare. They include a reference in a work of fiction from 1855 in which a drunken female cook is portrayed singing,

- Hee roar, up she rouses,

- What shall we do with the drunken sailor?[5]

A five-verse set of lyrics and tune were published in the third edition of Davis and Tozer's shanty collection, Sailor Songs or ‘Chanties’.[6] However, the title did not appear in any of the other major shanty collections or articles of the 19th century.

When John Masefield next published the lyrics in 1906, he called it a "bastard variety" of shanty which was "seldom used"[7]—an assertion supported by the lack of many earlier references. This style of shanty, called a "runaway chorus" by Masefield, and as a "walk away" or "stamp and go" shanty by others (see: Sea shanty:Types), was said to be used for tacking and which was sung in "quick time." The verses in Masefield's version asked what to do with a "drunken sailor," followed by a response, then followed by a question about a "drunken soldier," with an appropriate response.

Capt. W. B. Whall, a veteran English sailor of the 1860s–70s, was the next author to publish on "Drunken Sailor." He claimed that this was one of only two chanties that was sung in the British Royal Navy (where singing at work was generally frowned upon). Moreover, the song had largely gone out of use as a "walk away" shanty when the size of ships' crews was reduced and it was no longer possible to use that working method.[8] The lyrics given by Whall are essentially the same as those from Masefield: about a "drunken sailor," then a "drunken soldier." Significantly, he stated that these were the only lyrics, as evidently the task did not take long to complete.

- Chorus: Hoorah! And up she rises [3 times, appears before each verse]

- Early in the morning.

- What shall we do with a drunken sailor? [3 times]

- Early in the morning.

- Put him in the long-boat and make him bale her.

- Early in the morning.

- What shall we do with a drunken soldier?

- Early in the morning.

- Put him in the guardroom till he gets sober.

- Early in the morning.

The above-mentioned and other veteran sailors[9] characterized "Drunken Sailor" as a "walk away" shanty, thus providing a possible explanation for why it was not noted more often in the second half of the 19th century. Later sailors' recollections, however, attested that the song continued to be used as a shanty, but for other purposes. Richard Maitland, an American sailor of the 1870s, sang it for song collector Alan Lomax in 1939, when he explained,

Now this is a song that's usually sang when men are walking away with the slack of a rope, generally when the iron ships are scrubbing their bottom. After an iron ship has been twelve months at sea, there's a quite a lot of barnacles and grass grows onto her bottom. And generally, in the calm latitudes, up in the horse latitudes in the North Atlantic Ocean, usually they rig up a purchase for to scrub the bottom.[10]

Another American sailor of the 1870s, Frederick Pease Harlow, wrote in his shanty collection that "Drunken Sailor" could be used when hauling a halyard in "hand over hand" fashion to hoist the lighter sails.[11] This would be in contradistinction to the much more typical "halyards shanties," which were for heavier work with an entirely different sort of pacing and formal structure. Another author to ascribe a function, Richard Runciman Terry, also said it could be used for "hand over hand" hauling. Terry was one of few writers, however, to also state the shanty was used for heaving the windlass or capstan.[12]

As a popular song

"Drunken Sailor" began its life as a popular song on land at least as early as the 1900s, by which time it had been adopted as repertoire for glee singing at Eton College.[13][14] Elsewhere in England, by the 1910s, men had begun to sing it regularly at gatherings of the Savage Club of London.[15]

The song became popular on land in America as well. A catalogue of "folk-songs" from the Midwest included it in 1915, where it was said to be sung while dancing "a sort of reel."[16] More evidence of lands-folk's increasing familiarity with "Drunken Sailor" comes in the recording of a "Drunken Sailor Medley" (ca.1923) by U.S. Old Time fiddler John Baltzell. Evidently the tune's shared affinities with Anglo-Irish-American dance tunes helped it to become readapted as such, as Baltzell included it among a set of reels.

Classical composers utilized the song in compositions. Australian composer Percy Grainger incorporated the song into his piece "Scotch Strathspey And Reel" (1924). Malcolm Arnold used its melody in his Three Shanties for Woodwind Quintet, Op. 4 (1943).

The glut of writings on sailors' songs and published collections that came starting in the 1920s and which supported a revival of interest in shanty-singing for entertainment purposes on land. As such, R.R. Terry's very popular shanty collection, which had begun to serve as a resource for renditions of shanties on commercial recordings in the 1920s, was evidently used by the Robert Shaw Chorale for their 1961 rendition.[17] The Norman Luboff Choir recorded the song in 1959 with the yet uncharacteristic phrasing, "What'll we do...?"[18]

Notable recordings and performances

The song has been widely recorded under a number of titles by a range of performers including the King's Singers, Pete Seeger and The Irish Rovers. It also forms part of a contrapuntal section in the BBC Radio 4 UK Theme by Fritz Spiegl, in which it is played alongside Greensleeves.

Don Janse produced a particularly artistic arrangement in the early 1960s which has been included in several choral music anthologies. The arrangement was first recorded by The Idlers. This arrangement has been performed by several collegiate groups over the years, including the Yale Alley Cats.

This song has been recorded by Sam Spence under the name "Up She Rises", and is frequently used as background music for NFL Films.

The Belgian skiffle-singer Ferre Grignard covered the song in 1966.

A different version of this song titled "Drunken Whaler" accompanied the E3 trailer for the video game Dishonored, featuring darker lyrics and slightly slower tempo.[19]

Song text

Refrain:

- Weigh heigh and up she rises (/Hoo-ray and up she rises)

- Weigh heigh and up she rises (/Patent blocks of different sizes)[2]

- Weigh heigh and up she rises

- Early in the morning

Traditional verses:

- What shall we do with a drunken sailor,

- What shall we do with a drunken sailor,

- What shall we do with a drunken sailor,

- Early in the morning?

- Put/chuck him in the long boat till he's sober.[7]

- Put him in the long-boat and make him bale her.[8]

- What shall we do with a drunken soldier?[2]

- Put/lock him in the guard room 'til he gets sober.[7][2]

- Put him in the scuppers with a hose-pipe on him.(x3)[12]

- Pull out the plug and wet him all over[12]

- Tie him to the taffrail when she's yardarm under[12]

- Heave him by the leg in a runnin' bowline.[12]

- Scrape the hair off his chest with a hoop-iron razor.[2]

- Give 'im a dose of salt and water.[2]

- Stick on his back a mustard plaster.[2]

- Keep him there and make 'im bale 'er.[2]

- Give 'im a taste of the bosun's rope-end.[2]

- What'll we do with a Limejuice skipper?[2]

- Soak him in oil till he sprouts a flipper.[2]

- What shall we do with the Queen o' Sheba?[2]

- What shall we do with the Virgin Mary?[2]

Additional verses:

- Pronunciation of "early"

The word "early" is often pronounced as "earl-aye" in contemporary performances. Publications of 19th and early 20th century, however, did not note this was the case. Neither the field recordings of Richard Maitland by Alan Lomax (1939) nor those of several veteran sailors in Britain by James Madison Carpenter in the 1920s use this pronunciation. Yet on his popular recording of 1956, Burl Ives pronounced "earl-eye." Subsequently, Stan Hugill, whose influential Shanties from the Seven Seas was published in 1961, stated in that work that the word was "always" pronounced "earl-aye," but his statement is belied by the considerable body of earlier evidence.

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2009) |

- ^ Sharp, Cecil. 1914. English Folk-Chanteys. [need pg #]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Hugill, Stan. 1961. Shanties from the Seven Seas. London.

- ^ Olmsted, F.A. 1841. Incidents of a Whaling Voyage. New York: D. Appleton & Co. pp. 115–6.

- ^ Eckstorm, Fannie Hardy and Mary Winslow Smyth. 1927. Minstrelsy of Maine: Folk-songs and Ballads of the Woods and the Coast. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- ^ Dickens, Charles ed. 1855. "Two Dinner Failures." Household Words No. 256 (15 September 1855): 164–168.

- ^ Davis, J. and Ferris Tozer. 1891. Sailor Songs or ‘Chanties’. Third edition (enlarged). Boosey & Co.

- ^ a b c Masefield, John. 1906. A Sailor’s Garland. Methuen & Co.

- ^ a b Whall, Captain W.B. 1910. Sea Songs and Shanties. Brown, Son and Ferguson.

- ^ e.g. Williams, James H. “The Sailors’ ‘Chanties’.” The Independent (8 July 1909):76–83.

- ^ Various Artists. 2004. American Sea Songs & Shanties. Duncan Emrich, ed. The Library of Congress, Archive of Folk Culture. Rounder, CD, 18964-1519-2.

- ^ Harlow, Frederick Pease. 1962. Chanteying Aboard American Ships. Barre, Mass.: Barre Publishing Co.

- ^ a b c d e Terry, Richard Runciman. 1921. The Shanty Book, Part I. London: J. Curwen & Sons.

- ^ Malden, Charles Herbert. 1905. Recollections of an Eton Colleger: 1898-1902. Eton College: Spotswood and Co. P.73

- ^ "Truthful James." 1902. "Camp. A Prospect." Eton College Chronicle 977 (29 July 1902): 137.

- ^ Bullen, Frank. T. and W.F. Arnold. 1914. Songs of Sea Labour. London: Orpheus Music Publishing. P. [#].

- ^ Pound, Louise. 1915. "Folk-song of Nebraska and the Central West: A Syllabus." Nebraska Academy of Sciences Publications 9(3). p.152.

- ^ Robert Shaw Chorale. 1961. Sea Shanties. Living Stereo. LP.

- ^ Norman Luboff Choir, The. 1959. Songs of the British Isles. Columbia. LP.

- ^ "Dishonored sea shanty 'The Drunken Whaler' available for free, remix contest announced". Joystiq.com. September 16, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- ^ Wheatley, Dennis. 1936. They Found Atlantis. Hutchinson & Co. P.180.

- ^ Seeger, Pete. 1961. American Favorite Ballads Vol. 4. Folkways Records. LP.

- ^ Ives, Burl. 1956. Down to the Sea in Ships. Decca. LP.

- ^ Rise Up Singing (?)

- ^ This lyric appears to have been circulated among folk song singers after Oscar Brand's bawdy song "The Captain's Daughter," on Boating Songs and All that Bilge (Elektra, 1960, LP). The chorus runs, "What do we do with the captain's daughter...earl-eye in the morning?"

Further reading

- Stan Hugill, Shanties from the Seven Seas Mystic Seaport Museum 1994 ISBN 0-913372-70-6