Antimatter: Difference between revisions

m Typo/general fixing, replaced: a antimatter catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion → an antimatter catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion using AWB (8853) |

Switchcraft (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 446: | Line 446: | ||

}}</ref>}} |

}}</ref>}} |

||

---> |

---> |

||

===Weapons=== |

|||

(see [[antimatter weapon]]) |

|||

Less positively, antimatter has been considered as a trigger mechanism for nuclear weapons.<ref>[http://cui.unige.ch/isi/sscr/phys/anti-BPP-3.html Page discussing the possibility of using antimatter as a trigger for a thermonuclear explosion]</ref> A major obstacle is the difficulty of producing antimatter in large enough quantities, and there is no evidence that it will ever be feasible.<ref>[http://www.arxiv.org/abs/physics/0507114 Paper discussing the number of antiprotons required to ignite a thermonuclear weapon.]</ref> However, the U.S. Air Force funded studies of the physics of antimatter in the [[Cold War]], and began considering its possible use in weapons, not just as a trigger, but as the explosive itself.<ref>[http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/c/a/2004/10/04/MNGM393GPK1.DTL "Air Force pursuing antimatter weapons: Program was touted publicly, then came official gag order"]</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 10:30, 9 March 2013

| Antimatter |

|---|

|

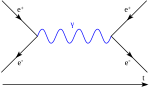

In particle physics, antimatter is material composed of antiparticles, which have the same mass as particles of ordinary matter but have opposite charge and quantum spin. Antiparticles bind with each other to form antimatter in the same way that normal particles bind to form normal matter. For example, a positron (the antiparticle of the electron, with symbol

e+

) and an antiproton (symbol

p

) can form an antihydrogen atom. Furthermore, mixing matter and antimatter can lead to the annihilation of both, in the same way that mixing antiparticles and particles does, thus giving rise to high-energy photons (gamma rays) or other particle–antiparticle pairs. The end result of antimatter meeting matter is a release of energy proportional to the mass as the mass-energy equivalence equation, E=mc2 shows.[1]

There is considerable speculation as to why the observable universe is apparently composed almost entirely of matter (as opposed to a mixture of matter and antimatter), whether there exist other places that are almost entirely composed of antimatter instead, and what sorts of technology might be possible if antimatter could be harnessed. At this time, the apparent asymmetry of matter and antimatter in the visible universe is one of the greatest unsolved problems in physics.[2] The process by which this asymmetry between particles and antiparticles developed is called baryogenesis.

History of the concept

The idea of negative matter appears in past theories of matter that have now been abandoned. Using the once popular vortex theory of gravity, the possibility of matter with negative gravity was discussed by William Hicks in the 1880s. Between the 1880s and the 1890s, Karl Pearson proposed the existence of "squirts" (sources) and sinks of the flow of aether. The squirts represented normal matter and the sinks represented negative matter. Pearson's theory required a fourth dimension for the aether to flow from and into.[3]

The term antimatter was first used by Arthur Schuster in two rather whimsical letters to Nature in 1898,[4] in which he coined the term. He hypothesized antiatoms, as well as whole antimatter solar systems, and discussed the possibility of matter and antimatter annihilating each other. Schuster's ideas were not a serious theoretical proposal, merely speculation, and like the previous ideas, differed from the modern concept of antimatter in that it possessed negative gravity.[5]

The modern theory of antimatter began in 1928, with a paper[6] by Paul Dirac. Dirac realised that his relativistic version of the Schrödinger wave equation for electrons predicted the possibility of antielectrons. These were discovered by Carl D. Anderson in 1932 and named positrons (a contraction of "positive electrons"). Although Dirac did not himself use the term antimatter, its use follows on naturally enough from antielectrons, antiprotons, etc.[7] A complete periodic table of antimatter was envisaged by Charles Janet in 1929.[8]

Notation

One way to denote an antiparticle is by adding a bar over the particle's symbol. For example, the proton and antiproton are denoted as

p

and

p

, respectively. The same rule applies if one were to address a particle by its constituent components. A proton is made up of

u

u

d

quarks, so an antiproton must therefore be formed from

u

u

d

antiquarks. Another convention is to distinguish particles by their electric charge. Thus, the electron and positron are denoted simply as

e−

and

e+

respectively. However, to prevent confusion, the two conventions are never mixed.

Origin and asymmetry

Almost all matter observable from the Earth seems to be made of matter rather than antimatter. If antimatter-dominated regions of space existed, the gamma rays produced in annihilation reactions along the boundary between matter and antimatter regions would be detectable.[9]

Antiparticles are created everywhere in the universe where high-energy particle collisions take place. High-energy cosmic rays impacting Earth's atmosphere (or any other matter in the Solar System) produce minute quantities of antiparticles in the resulting particle jets, which are immediately annihilated by contact with nearby matter. They may similarly be produced in regions like the center of the Milky Way and other galaxies, where very energetic celestial events occur (principally the interaction of relativistic jets with the interstellar medium). The presence of the resulting antimatter is detectable by the two gamma rays produced every time positrons annihilate with nearby matter. The frequency and wavelength of the gamma rays indicate that each carries 511 keV of energy (i.e., the rest mass of an electron multiplied by c2).

Recent observations by the European Space Agency's INTEGRAL satellite may explain the origin of a giant cloud of antimatter surrounding the galactic center. The observations show that the cloud is asymmetrical and matches the pattern of X-ray binaries (binary star systems containing black holes or neutron stars), mostly on one side of the galactic center. While the mechanism is not fully understood, it is likely to involve the production of electron–positron pairs, as ordinary matter gains tremendous energy while falling into a stellar remnant.[10][11]

Antimatter may exist in relatively large amounts in far-away galaxies due to cosmic inflation in the primordial time of the universe. Antimatter galaxies, if they exist, are expected to have the same chemistry and absorption and emission spectra as normal-matter galaxies, and their astronomical objects would be observationally identical, making them difficult to distinguish.[12] NASA is trying to determine if such galaxies exist by looking for X-ray and gamma-ray signatures of annihilation events in colliding superclusters.[13]

Natural production

Positrons are produced naturally in β+ decays of naturally occurring radioactive isotopes (for example, potassium-40) and in interactions of gamma quanta (emitted by radioactive nuclei) with matter. Antineutrinos are another kind of antiparticle created by natural radioactivity (β− decay). Many different kinds of antiparticles are also produced by (and contained in) cosmic rays. Recent (as of January 2011) research by the American Astronomical Society has discovered antimatter (positrons) originating above thunderstorm clouds; positrons are produced in gamma-ray flashes created by electrons accelerated by strong electric fields in the clouds.[14] Antiprotons have also been found to exist in the Van Allen Belts around the Earth by the PAMELA module.[15][16]

Artificial production

Antiparticles are also produced in any environment with a sufficiently high temperature (mean particle energy greater than the pair production threshold). During the period of baryogenesis, when the universe was extremely hot and dense, matter and antimatter were continually produced and annihilated. The presence of remaining matter, and absence of detectable remaining antimatter,[17] also called baryon asymmetry, is attributed to violation of the CP-symmetry relating matter to antimatter. The exact mechanism of this violation during baryogenesis remains a mystery.

Positrons can also be produced by radioactive

β+

decay, but this mechanism can occur both naturally and artificially.

Positrons

Positrons were reported[18] in November 2008 to have been generated by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in larger numbers than by any previous synthetic process. A laser drove electrons through a millimeter-radius gold target's nuclei, which caused the incoming electrons to emit energy quanta that decayed into both matter and antimatter. Positrons were detected at a higher rate and in greater density than ever previously detected in a laboratory. Previous experiments made smaller quantities of positrons using lasers and paper-thin targets; however, new simulations showed that short, ultra-intense lasers and millimeter-thick gold are a far more effective source.[19]

Antiprotons, antineutrons, and antinuclei

The existence of the antiproton was experimentally confirmed in 1955 by University of California, Berkeley physicists Emilio Segrè and Owen Chamberlain, for which they were awarded the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physics.[20] An antiproton consists of two up antiquarks and one down antiquark (

u

u

d

). The properties of the antiproton that have been measured all match the corresponding properties of the proton, with the exception of the antiproton having opposite electric charge and magnetic moment from the proton. Shortly afterwards, in 1956, the antineutron was discovered in proton–proton collisions at the Bevatron (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) by Bruce Cork and colleagues.[21]

In addition to antibaryons, anti-nuclei consisting of multiple bound antiprotons and antineutrons have been created. These are typically produced at energies far too high to form antimatter atoms (with bound positrons in place of electrons). In 1965, a group of researchers led by Antonino Zichichi reported production of nuclei of antideuterium at the Proton Synchrotron at CERN.[22] At roughly the same time, observations of antideuterium nuclei were reported by a group of American physicists at the Alternating Gradient Synchrotron at Brookhaven National Laboratory.[23]

Antihydrogen atoms

In 1995, CERN announced that it had successfully brought into existence nine antihydrogen atoms by implementing the SLAC/Fermilab concept during the PS210 experiment. The experiment was performed using the Low Energy Antiproton Ring (LEAR), and was led by Walter Oelert and Mario Macri[citation needed]. Fermilab soon confirmed the CERN findings by producing approximately 100 antihydrogen atoms at their facilities. The antihydrogen atoms created during PS210 and subsequent experiments (at both CERN and Fermilab) were extremely energetic ("hot") and were not well suited to study. To resolve this hurdle, and to gain a better understanding of antihydrogen, two collaborations were formed in the late 1990s, namely, ATHENA and ATRAP. In 2005, ATHENA disbanded and some of the former members (along with others) formed the ALPHA Collaboration, which is also based at CERN. The primary goal of these collaborations is the creation of less energetic ("cold") antihydrogen, better suited to study[citation needed].

In 1999, CERN activated the Antiproton Decelerator, a device capable of decelerating antiprotons from 3.5 GeV to 5.3 MeV — still too "hot" to produce study-effective antihydrogen, but a huge leap forward. In late 2002 the ATHENA project announced that they had created the world's first "cold" antihydrogen.[24] The ATRAP project released similar results very shortly thereafter.[25] The antiprotons used in these experiments were cooled by decelerating them with the Antiproton Decelerator, passing them through a thin sheet of foil, and finally capturing them in a Penning-Malmberg trap.[26] The overall cooling process is workable, but highly inefficient; approximately 25 million antiprotons leave the Antiproton Decelerator and roughly 25,000 make it to the Penning-Malmberg trap, which is about 1⁄1000 or 0.1% of the original amount.

The antiprotons are still hot when initially trapped. To cool them further, they are mixed into an electron plasma. The electrons in this plasma cool via cyclotron radiation, and then sympathetically cool the antiprotons via Coulomb collisions. Eventually, the electrons are removed by the application of short-duration electric fields, leaving the antiprotons with energies less than 100 meV.[27] While the antiprotons are being cooled in the first trap, a small cloud of positrons is captured from radioactive sodium in a Surko-style positron accumulator.[28] This cloud is then recaptured in a second trap near the antiprotons. Manipulations of the trap electrodes then tip the antiprotons into the positron plasma, where some combine with antiprotons to form antihydrogen. This neutral antihydrogen is unaffected by the electric and magnetic fields used to trap the charged positrons and antiprotons, and within a few microseconds the antihydrogen hits the trap walls, where it annihilates. Some hundreds of millions of antihydrogen atoms have been made in this fashion.

Most of the sought-after high-precision tests of the properties of antihydrogen could only be performed if the antihydrogen were trapped, that is, held in place for a relatively long time. While antihydrogen atoms are electrically neutral, the spins of their component particles produce a magnetic moment. These magnetic moments can interact with an inhomogeneous magnetic field; some of the antihydrogen atoms can be attracted to a magnetic minimum. Such a minimum can be created by a combination of mirror and multipole fields.[29] Antihydrogen can be trapped in such a magnetic minimum (minimum-B) trap; in November 2010, the ALPHA collaboration announced that they had so trapped 38 antihydrogen atoms for about a sixth of a second.[30][31] This was the first time that neutral antimatter had been trapped.

On 26 April 2011, ALPHA announced that they had trapped 309 antihydrogen atoms, some for as long as 1,000 seconds (about 17 minutes). This was longer than neutral antimatter had ever been trapped before.[32][33]

The biggest limiting factor in the large-scale production of antimatter is the availability of antiprotons. Recent data released by CERN states that, when fully operational, their facilities are capable of producing ten million antiprotons per minute.[34] Assuming a 100% conversion of antiprotons to antihydrogen, it would take 100 billion years to produce 1 gram or 1 mole of antihydrogen (approximately 6.02×1023 atoms of antihydrogen).

Antihelium

Antihelium-3 nuclei (3

He

) were first observed in the 1970s in proton-nucleus collision experiments[35]

and later created in nucleus-nucleus collision experiments.[36] Nucleus-nucleus collisions produce antinuclei through the coalescense of antiprotons and antineutrons created in these reactions. In 2011, the STAR detector reported the observation of Antihelium-4 nuclei (4

He

).[37]

Preservation

Antimatter cannot be stored in a container made of ordinary matter because antimatter reacts with any matter it touches, annihilating itself and an equal amount of the container. Antimatter in the form of charged particles can be contained by a combination of electric and magnetic fields, in a device called a Penning trap. This device cannot, however, contain antimatter that consists of uncharged particles, for which atomic traps are used. In particular, such a trap may use the dipole moment (electric or magnetic) of the trapped particles. At high vacuum, the matter or antimatter particles can be trapped and cooled with slightly off-resonant laser radiation using a magneto-optical trap or magnetic trap. Small particles can also be suspended with optical tweezers, using a highly focused laser beam.[citation needed]

Cost

Scientists claim that antimatter is the costliest material to make.[38] In 2006, Gerald Smith estimated $250 million could produce 10 milligrams of positrons[39] (equivalent to $25 billion per gram); in 1999, NASA gave a figure of $62.5 trillion per gram of antihydrogen.[38] This is because production is difficult (only very few antiprotons are produced in reactions in particle accelerators), and because there is higher demand for other uses of particle accelerators. According to CERN, it has cost a few hundred million Swiss Francs to produce about 1 billionth of a gram (the amount used so far for particle/antiparticle collisions).[40]

Several studies funded by the NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts are exploring whether it might be possible to use magnetic scoops to collect the antimatter that occurs naturally in the Van Allen belt of the Earth, and ultimately, the belts of gas giants, like Jupiter, hopefully at a lower cost per gram.[41]

Uses

Medical

Matter-antimatter reactions have practical applications in medical imaging, such as positron emission tomography (PET). In positive beta decay, a nuclide loses surplus positive charge by emitting a positron (in the same event, a proton becomes a neutron, and a neutrino is also emitted). Nuclides with surplus positive charge are easily made in a cyclotron and are widely generated for medical use. Antiprotons have also been shown within laboratory experiments to have the potential to treat certain cancers, in a similar method currently used for ion (proton) therapy.[42]

Fuel

The scarcity of antimatter means that it is not readily available for use as fuel. Any antimatter propulsion would require engine construction so as to prevent the annihilation of all the fuel simultaneously. Anti-matter could be used as a fuel for interplanetary travel or interstellar travel[43] as part of an antimatter catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion or other antimatter rocketry, such as the redshift rocket. Since the energy density of antimatter is higher than that of conventional fuels, an antimatter-fueled spacecraft would have a higher thrust-to-weight ratio than a conventional spacecraft.

In matter-antimatter collisions resulting in photon emission, the entire rest mass of the particles is converted to kinetic energy. The energy per unit mass (9×1016 J/kg) is about 10 orders of magnitude greater than typical chemical energies,[44] and about 3 orders of magnitude greater than the nuclear potential energy that can be liberated, today, using nuclear fission (about 200 MeV per atomic nucleus that undergoes nuclear fission,[45] or 8×1013 J/kg), and about 2 orders of magnitude greater than the best possible results expected from fusion (about 6.3×1014 J/kg for the proton-proton chain). The reaction of 1 kg of antimatter with 1 kg of matter would produce 1.8×1017 J (180 petajoules) of energy (by the mass-energy equivalence formula, E = mc2), or the rough equivalent of 43 megatons of TNT – slightly less than the yield of the 27,000 kg Tsar Bomb, the largest thermonuclear weapon ever detonated.

Not all of that energy can be utilized by any realistic propulsion technology because, while electron-positron reactions result in gamma ray photons, in reactions between protons and antiprotons, their energy is converted into relativistic neutral and charged pions. While the neutral pions decay into high-energy photons, the charged pions decay into a combination of neutrinos (carrying about 22% of the energy of the charged pions) and unstable charged muons (carrying about 78% of the charged pion energy), with the muons then decaying into a combination of electrons, positrons and neutrinos (cf. muon decay; the neutrinos from this decay carry about 2/3 of the energy of the muons, meaning that from the original charged pions, the total fraction of their energy converted to neutrinos by one route or another would be about 0.22 + (2/3)*0.78 = 0.74). Gamma radiation can be largely absorbed and converted into heat energy, though some is bound to be lost. Neutrinos very rarely interact with any form of matter, so for all intents and purposes, the energy converted into neutrinos can be considered lost.[46]

Weapons

(see antimatter weapon)

Less positively, antimatter has been considered as a trigger mechanism for nuclear weapons.[47] A major obstacle is the difficulty of producing antimatter in large enough quantities, and there is no evidence that it will ever be feasible.[48] However, the U.S. Air Force funded studies of the physics of antimatter in the Cold War, and began considering its possible use in weapons, not just as a trigger, but as the explosive itself.[49]

See also

- Antimatter comet

- Ambiplasma

- Particle accelerator

- Antiparticle

- Antihydrogen

- Gravitational interaction of antimatter

References

- ^ http://news.discovery.com/space/pamela-spots-a-smidgen-of-antimatter-110811.html

- ^ David Tenenbaum, David, One step closer: UW-Madison scientists help explain scarcity of anti-matter, University of Wisconsin—Madison News, December 26, 2012

- ^ H. Kragh (2002). Quantum Generations: A History of Physics in the Twentieth Century. Princeton University Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 0-691-09552-3.

- ^ A. Schuster (1898). "Potential Matter.—A Holiday Dream". Nature. 58 (1503): 367. Bibcode:1898Natur..58..367S. doi:10.1038/058367a0.

- ^ E. R. Harrison (16 March 2000). Cosmology: The Science of the Universe (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 266, 433. ISBN 0-521-66148-X.

- ^ P. A. M. Dirac (1928). "The Quantum Theory of the Electron". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London: Series A. 117 (778): 610–624. Bibcode:1928RSPSA.117..610D. doi:10.1098/rspa.1928.0023. JSTOR 94981.

- ^ M. Kaku, J. T. Thompson (1997). Beyond Einstein: The Cosmic Quest for the Theory of the Universe. Oxford University Press. pp. 179–180. ISBN 0-19-286196-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ P. J. Stewart (2010). "Charles Janet: Unrecognized genius of the periodic system". Foundations of Chemistry. 12 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1007/s10698-008-9062-5.

- ^ E. Sather (1999). "The Mystery of the Matter Asymmetry" (PDF). Beam Line. 26 (1): 31.

- ^ "Integral discovers the galaxy's antimatter cloud is lopsided". European Space Agency. 9 January 2008. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ G. Weidenspointner; et al. (2008). "An asymmetric distribution of positrons in the Galactic disk revealed by γ-rays". Nature. 451 (7175): 159–162. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..159W. doi:10.1038/nature06490. PMID 18185581.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Close, F. E. (22 January 2009). Antimatter. Oxford University Press US. p. 114. ISBN 0-19-955016-6.

- ^ "Searching for Primordial Antimatter". NASA. 30 October 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ "Antimatter caught streaming from thunderstorms on Earth". BBC. 11 January 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Adriani, O.; Barbarino, G. C.; Bazilevskaya, G. A.; Bellotti, R.; Boezio, M.; Bogomolov, E. A.; Bongi, M.; Bonvicini, V.; Borisov, S. (2011). "The Discovery of Geomagnetically Trapped Cosmic-Ray Antiprotons". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 737 (2): L29. arXiv:1107.4882v1. Bibcode:2011ApJ...737L..29A. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/737/2/L29.

- ^ Than, Ker (10 August 2011). "Antimatter Found Orbiting Earth—A First". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ^ "What's the Matter with Antimatter?". NASA. 29 May 2000. Archived from the original on 4 June 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Billions of particles of anti-matter created in laboratory" (Press release). Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. 3 November 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ^ "Laser creates billions of antimatter particles". Cosmos Magazine. 19 November 2008. Archived from the original on 22 May 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "All Nobel Prizes in Physics".

- ^ "Breaking Through: A Century of Physics at Berkeley, 1868–1968". Regents of the University of California. 2006. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Massam, T; Muller, Th.; Righini, B.; Schneegans, M.; Zichichi, A. (1965). "Experimental observation of antideuteron production". Il Nuovo Cimento. 39: 10–14. Bibcode:1965NCimS..39...10M. doi:10.1007/BF02814251.

- ^ Dorfan, D. E; Eades, J.; Lederman, L. M.; Lee, W.; Ting, C. C. (1965). "Observation of Antideuterons". Phys. Rev. Lett. 14 (24): 1003–1006. Bibcode:1965PhRvL..14.1003D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.14.1003.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ M. Amoretti; et al. (2002). "Production and detection of cold antihydrogen atoms". Nature. 419 (6906): 456. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..456A. doi:10.1038/nature01096. PMID 12368849.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ G. Gabrielse; et al. (2002). "Background-free observation of cold antihydrogen with field ionization analysis of its states". Physical Review Letters. 89 (21): 213401. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..89u3401G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.213401. PMID 12443407.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ J. H. Malmberg, J. S. deGrassie (1975). "Properties of a nonneutral plasma". Physical Review Letters. 35 (9): 577. Bibcode:1975PhRvL..35..577M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.35.577.

- ^ G. Gabrielse; et al. (1989). "Cooling and slowing of trapped antiprotons below 100 meV". Physical Review Letters. 63 (13): 1360. Bibcode:1989PhRvL..63.1360G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.63.1360.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ C. M. Surko, R. G. Greaves (2004). "Emerging science and technology of antimatter plasmas and trap-based beams". Physics of Plasmas. 11 (5): 2333. Bibcode:2004PhPl...11.2333S. doi:10.1063/1.1651487.

- ^ D. E. Pritchard; Heinz, T.; Shen, Y. (1983). "Cooling neutral atoms in a magnetic trap for precision spectroscopy". Physical Review Letters. 51 (21): 1983. Bibcode:1983PhRvL..51.1983T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.51.1983.

- ^ Andresen; Ashkezari, M. D.; Baquero-Ruiz, M.; Bertsche, W.; Bowe, P. D.; Butler, E.; Cesar, C. L.; Chapman, S.; Charlton, M.; et al. (2010). "Trapped antihydrogen". Nature. 468 (7324): 673–676. Bibcode:2010Natur.468..673A. doi:10.1038/nature09610. PMID 21085118.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Antimatter atoms produced and trapped at CERN". CERN. 17 November 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ ALPHA Collaboration; Andresen; Ashkezari; Baquero-Ruiz; Bertsche; Butler; Cesar; Deller; Eriksson (26 April 2011). "Title: Confinement of antihydrogen for 1000 seconds". arXiv:1104.4982 [physics.atom-ph].

- ^ ALPHA Collaboration; Andresen. "Confinement of antihydrogen for 1,000 seconds". Nature Physics. 7 (7). Bibcode:2011NatPh...7..558T. doi:10.1038/nphys2025.

- ^ N. Madsen (2010). "Cold antihydrogen: a new frontier in fundamental physics". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 368 (1924): 1924ff. Bibcode:2010RSPTA.368.3671M. doi:10.1098/rsta.2010.0026. PMID 20603376.

- ^ Y.M. Antipov; et al. (1974). "Observation of antihelium3 (in Russian)". Yad. Fiz. 12: 311.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ R. Arsenescu; et al. (2003). "Antihelium-3 production in lead-lead collisions at 158 A GeV/c". New Journal of Physics. 5: 1. Bibcode:2003NJPh....5....1A. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/5/1/301.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ H. Agakishiev; et al. (2011). "Observation of the antimatter helium-4 nucleus". 1103: 3312. arXiv:1103.3312. Bibcode:2011arXiv1103.3312S.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b "Reaching for the stars: Scientists examine using antimatter and fusion to propel future spacecraft". NASA. 12 April 1999. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

Antimatter is the most expensive substance on Earth

- ^ B. Steigerwald (14 March 2006). "New and Improved Antimatter Spaceship for Mars Missions". NASA. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

"A rough estimate to produce the 10 milligrams of positrons needed for a human Mars mission is about 250 million dollars using technology that is currently under development," said Smith.

- ^ "Antimatter Questions & Answers". CERN. 2001. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ J. Bickford. "Extraction of Antiparticles Concentrated in Planetary Magnetic Fields" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ^ "Antiproton portable traps and medical applications" (PDF).

- ^ G. R. Schmidt (1999). "Antimatter Production for Near-Term Propulsion Applications". Nuclear Physics and High-Energy Physics. Marshall Space Flight Center, NASA. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ (compared to TNT at 4.2×106 J/kg, and formation of water at 1.56×107 J/kg)

- ^ M. G. Sowerby. "§4.7 Nuclear fission and fusion, and neutron interactions". Kaye & Laby: Table of Physical & Chemical Constants. National Physical Laboratory. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ S. K. Borowski (1987). "Comparison of Fusion/Antiproton Propulsion systems" (PDF). NASA Technical Memorandum 107030. NASA. pp. 5–6 (pp. 6–7 of pdf). AIAA–87–1814. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Page discussing the possibility of using antimatter as a trigger for a thermonuclear explosion

- ^ Paper discussing the number of antiprotons required to ignite a thermonuclear weapon.

- ^ "Air Force pursuing antimatter weapons: Program was touted publicly, then came official gag order"

Further reading

- G. Fraser (18 May 2000). Antimatter, The Ultimate Mirror. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65252-0.

External links

- Antimatter on In Our Time at the BBC

- Freeview Video 'Antimatter' by the Vega Science Trust and the BBC/OU

- CERN Webcasts (RealPlayer required)

- What is Antimatter? (from the Frequently Asked Questions at the Center for Antimatter-Matter Studies)

- FAQ from CERN with lots of information about antimatter aimed at the general reader, posted in response to antimatter's fictional portrayal in Angels & Demons

- What is direct CP-violation?

- Animated illustration of antihydrogen production at CERN from the Exploratorium.