Heliosphere: Difference between revisions

→Heliopause: Corrected a spelling error ("Heiliopause" > "heliopause"). |

m →Outer structure: clarified wording. |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

The heliosphere's outer structure is determined by the interactions between the solar wind and the winds of interstellar space. The solar wind streams away from the Sun in all directions at speeds of several hundred km/s in the Earth's vicinity. At some distance from the Sun, well beyond the orbit of [[Neptune]], this supersonic wind must slow down to meet the gases in the [[interstellar medium]]. This takes place in several stages: |

The heliosphere's outer structure is determined by the interactions between the solar wind and the winds of interstellar space. The solar wind streams away from the Sun in all directions at speeds of several hundred km/s in the Earth's vicinity. At some distance from the Sun, well beyond the orbit of [[Neptune]], this supersonic wind must slow down to meet the gases in the [[interstellar medium]]. This takes place in several stages: |

||

* The solar wind is traveling at [[supersonic]] speeds within the Solar System. At the '''termination shock''', a standing [[shock wave]], the solar wind falls below the speed of sound and becomes [[Speed of sound|subsonic]]. |

* The solar wind is traveling at [[supersonic]] speeds within the Solar System. At the '''termination shock''', a standing [[shock wave]], the solar wind falls below the speed of sound and becomes [[Speed of sound|subsonic]]. |

||

* It was previously held that, once subsonic, the solar wind might be affected by the ambient flow of the interstellar medium: Its pressures were theorized to cause the solar wind to form a nose on one side and comet-like heliotail behind. The area called the '''heliosheath'''. However, scientific results in 2009 showed that this model is incorrect.<ref name=jhopkins/><ref name=ibex09/> |

* It was previously held that, once subsonic, the solar wind might be affected by the ambient flow of the interstellar medium: Its pressures were theorized to cause the solar wind to form a nose on one side and comet-like heliotail behind. The area called the '''heliosheath'''. However, scientific results in 2009 showed that this model is incorrect.<ref name=jhopkins/><ref name=ibex09/> As of 2011, it is thought to be filled with a magnetic bubble "foam".<ref name=surprise/> |

||

* The outer surface of the heliosheath, where the heliosphere meets the interstellar medium, is called the '''heliopause'''. This is the edge of the entire heliosphere. Scientific results in 2009 adjusted this model.<ref name=jhopkins/><ref name=ibex09/> |

* The outer surface of the heliosheath, where the heliosphere meets the interstellar medium, is called the '''heliopause'''. This is the edge of the entire heliosphere. Scientific results in 2009 adjusted this model.<ref name=jhopkins/><ref name=ibex09/> |

||

* In theory, the heliopause causes turbulence in the interstellar medium as the sun orbits the [[Galactic Center]]. This '''[[bow shock]]''', outside the heliopause, would be a turbulent region caused by the pressure of the advancing heliopause against the [[interstellar medium]]. However, data from the [[Interstellar Boundary Explorer]] suggests that a bow shock doesn't exist because the velocity of the Sun through the interstellar medium is too low for the shock to form.<ref name=physorg20120511>{{citation | title=New Interstellar Boundary Explorer data show heliosphere's long-theorized bow shock does not exist | date=May 10, 2012 | work=Phys.org | url=http://phys.org/news/2012-05-interstellar-boundary-explorer-heliosphere-long-theorized.html | accessdate=2012-02-11 }}</ref> |

* In theory, the heliopause causes turbulence in the interstellar medium as the sun orbits the [[Galactic Center]]. This '''[[bow shock]]''', outside the heliopause, would be a turbulent region caused by the pressure of the advancing heliopause against the [[interstellar medium]]. However, data from the [[Interstellar Boundary Explorer]] suggests that a bow shock doesn't exist because the velocity of the Sun through the interstellar medium is too low for the shock to form.<ref name=physorg20120511>{{citation | title=New Interstellar Boundary Explorer data show heliosphere's long-theorized bow shock does not exist | date=May 10, 2012 | work=Phys.org | url=http://phys.org/news/2012-05-interstellar-boundary-explorer-heliosphere-long-theorized.html | accessdate=2012-02-11 }}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 16:49, 26 March 2013

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (December 2012) |

The heliosphere is a region of space dominated by Earth's Sun, a sort of bubble of charged particles in the space surrounding the Solar System, "blown" into the interstellar medium (the hydrogen and helium gas that permeates the galaxy) by the solar wind. Although electrically neutral atoms from the extra-solar volume can penetrate this bubble, virtually all of the material in the heliosphere emanates from the Sun itself. The Sun's Corona is so hot that particles reach escape velocity, streaming outwards at 300 to 800 km/s (1 to 2 million mph) producing the solar wind.[1]

For the first ten billion kilometers of its radius[citation needed], the solar wind travels at over 1,000,000 km/h.[2] As it begins to interact with the interstellar medium, it slows down before finally ceasing altogether. The point where the solar wind begins to slow is called the termination shock; the solar wind continues to slow as it passes through the heliosheath leading to a boundary called the heliopause where the interstellar medium and solar wind pressures balance. The termination shock was successfully detected by both Voyager 1 in 2004,[3] and Voyager 2 in 2007.[4]

As the sun is moving through space it was assumed that beyond the heliopause there might be a bow shock, similar to a bow wave created as a ship passes through water, where the interstellar medium collides with the heliosphere. However, data from the Interstellar Boundary Explorer suggests that the velocity of the Sun through the interstellar medium is too low for a bow shock to form.[5] Also, Cassini and IBEX data challenged the "heliotail" theory in 2009.[6][7] Voyager data led to a new theory that the heliosheath has "magnetic bubbles" and a stagnation zone.[8][9]

The 'stagnation region' within the heliosheath, starting around 113 AU, was detected by Voyager 1 in 2010.[8] There the solar wind velocity drops to zero, the magnetic field intensity doubles, and high-energy electrons from the galaxy increase 100-fold.[8] Starting in May 2012 at 120 AU, Voyager 1 detected a sudden increase in cosmic rays, an apparent signature of approach to the heliopause.[10] In December 2012 NASA announced that in late August 2012 Voyager 1, at about 122 AU from the Sun, entered a new region they called the "magnetic highway", an area still under the influence of the Sun, but with some dramatic differences.[3]

Solar wind

The solar wind consists of particles (ionized atoms from the solar corona) and fields (in particular, magnetic fields). As the Sun rotates once in approximately 27 days, the magnetic field transported by the solar wind gets wrapped into a spiral. Variations in the Sun's magnetic field are carried outward by the solar wind and can produce magnetic storms in the Earth's own magnetosphere.

Structure

Heliospheric current sheet

The heliospheric current sheet is a ripple in the heliosphere created by the Sun's rotating magnetic field. Extending throughout the heliosphere, it is considered the largest structure in the Solar System and is said to resemble a "ballerina's skirt".[11]

Outer structure

The heliosphere's outer structure is determined by the interactions between the solar wind and the winds of interstellar space. The solar wind streams away from the Sun in all directions at speeds of several hundred km/s in the Earth's vicinity. At some distance from the Sun, well beyond the orbit of Neptune, this supersonic wind must slow down to meet the gases in the interstellar medium. This takes place in several stages:

- The solar wind is traveling at supersonic speeds within the Solar System. At the termination shock, a standing shock wave, the solar wind falls below the speed of sound and becomes subsonic.

- It was previously held that, once subsonic, the solar wind might be affected by the ambient flow of the interstellar medium: Its pressures were theorized to cause the solar wind to form a nose on one side and comet-like heliotail behind. The area called the heliosheath. However, scientific results in 2009 showed that this model is incorrect.[6][7] As of 2011, it is thought to be filled with a magnetic bubble "foam".[12]

- The outer surface of the heliosheath, where the heliosphere meets the interstellar medium, is called the heliopause. This is the edge of the entire heliosphere. Scientific results in 2009 adjusted this model.[6][7]

- In theory, the heliopause causes turbulence in the interstellar medium as the sun orbits the Galactic Center. This bow shock, outside the heliopause, would be a turbulent region caused by the pressure of the advancing heliopause against the interstellar medium. However, data from the Interstellar Boundary Explorer suggests that a bow shock doesn't exist because the velocity of the Sun through the interstellar medium is too low for the shock to form.[5]

Termination shock

The termination shock is the point in the heliosphere where the solar wind slows down to subsonic speed (relative to the star) because of interactions with the local interstellar medium. This causes compression, heating, and a change in the magnetic field. In the Solar System the termination shock is believed to be 75 to 90 astronomical units[13] from the Sun. In 2004, Voyager 1 crossed the Sun's termination shock followed by Voyager 2 in 2007.[14]

The shock arises because solar wind particles are emitted from stars at about 400 km/s, while the speed of sound (in the interstellar medium) is about 100 km/s. (The exact speed depends on the density, which fluctuates considerably.) The interstellar medium, although very low in density, nonetheless has a constant pressure associated with it; the pressure from the solar wind decreases with the square of the distance from the star. As one moves far enough away from the star, the pressure from the interstellar medium becomes sufficient to slow the solar wind down to below its speed of sound; this causes a shock wave.

Other termination shocks can be seen in terrestrial systems; perhaps the easiest may be seen by simply running a water tap into a sink creating a hydraulic jump. Upon hitting the floor of the sink, the flowing water spreads out at a speed that is higher than the local wave speed, forming a disk of shallow, rapidly diverging flow (analogous to the tenuous, supersonic solar wind). Around the periphery of the disk, a shock front or wall of water forms; outside the shock front, the water moves slower than the local wave speed (analogous to the subsonic interstellar medium).

Going outward from the Sun, the termination shock is followed by the heliopause, where solar wind particles are stopped by the interstellar medium.

Evidence presented at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in May 2005 by Dr. Ed Stone suggests that the Voyager 1 spacecraft passed termination shock in December 2004, when it was about 94 AU from the Sun, by virtue of the change in magnetic readings taken from the craft. In contrast, Voyager 2 began detecting returning particles when it was only 76 AU from the Sun, in May 2006. This implies that the heliosphere may be irregularly shaped, bulging outwards in the Sun's northern hemisphere and pushed inward in the south.[15]

The Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) mission gathered more data on the Solar System's termination shock.

Heliosheath

The heliosheath is the region of the heliosphere beyond the termination shock. Here the wind is slowed, compressed and made turbulent by its interaction with the interstellar medium. Its distance from the Sun is approximately 80 to 100 astronomical units (AU) at its closest point.

A proposed model hypothesizes that the heliosheath is shaped like the coma of a comet, and trails several times that distance in the direction opposite to the Sun's path through space. At its windward side, its thickness is estimated to be between 10 and 100 AU.[16] However, scientific results in 2009 showed that model may be incorrect.[6][7]

The Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 mission currently includes studying the heliosheath. In late 2010, Voyager 1 reached a region of the heliosheath where the solar wind's velocity had dropped to zero.[17][18][19][20] In 2011, astronomers announced that the Voyagers had determined that the heliosheath is not smooth, but is filled with 100 million-mile-wide bubbles created by the impact of the solar wind and the interstellar medium.[21][22] Voyager 1 and 2 began detecting evidence for the bubbles in 2007 and 2008, respectively.[22] The probably sausage-shaped bubbles are formed by magnetic reconnection between oppositely oriented sectors of the solar magnetic field as the solar wind slows down.[22] They probably represent self-contained structures that have detached from the interplanetary magnetic field.[21][22]

Heliopause

The heliopause is the theoretical boundary where the Sun's solar wind is stopped by the interstellar medium; where the solar wind's strength is no longer great enough to push back the stellar winds of the surrounding stars. The crossing of the heliopause should be signaled by a sharp drop in the temperature of charged particles,[18] a change in the direction of the magnetic field, and an increase in the amount of galactic cosmic rays.[10] In May 2012, Voyager 1 detected a rapid increase in such cosmic rays (a 9% increase in a month, following a more gradual increase of 25% from Jan. 2009 to Jan. 2012), suggesting it was approaching the heliopause.[10] On March 20, 2013 a study was released that suggested that Voyager 1 likely cleared the heliopause on August 25, 2012, judging by drastic changes in Radiation levels.

Hypotheses

According to one hypothesis,[23] there exists a region of hot hydrogen known as the hydrogen wall between the bow shock and the heliopause. The wall is composed of interstellar material interacting with the edge of the heliosphere.

Another hypothesis suggests that the heliopause could be smaller on the side of the Solar System facing the Sun's orbital motion through the galaxy. It may also vary depending on the current velocity of the solar wind and the local density of the interstellar medium. It is known to lie far outside the orbit of Neptune. The current mission of the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft is to find and study the termination shock, heliosheath, and heliopause. Voyager 1 reached the termination shock on May 23–24, 2005,[24] and Voyager 2 reached it on August 30, 2007 according to NASA.[25] Meanwhile, the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) mission is attempting to image the heliopause from Earth orbit within two years of its 2008 launch. Initial results (October 2009) from IBEX suggest that previous assumptions are insufficiently cognisant of the true complexities of the heliopause.[26]

When particles emitted by the sun bump into the interstellar ones, they slow down while releasing energy. Many particles accumulate in and around the heliopause, highly energised by their negative acceleration, creating a shock wave.

An alternative definition is that the heliopause is the magnetopause between the Solar System's magnetosphere and the galaxy's plasma currents.

Bow shock

Hubble, 1995

By 2012, it was determined the Sun has no bow shock.[5] Before then, it was hypothesized that the Sun had a bow shock produced in its travels within the interstellar medium (see image). The shock is named from its resemblance to the wake left by a ship's bow and is formed for similar reasons, though of plasma instead of water. Bow shocks will occur if the interstellar medium is moving supersonically "toward" the sun, since its solar wind moves "away" from the sun supersonically. When the interstellar wind hits the heliosphere it slows and creates a region of turbulence. NASA's Robert Nemiroff and Jerry Bonnell believed the solar bow shock occurred at about 230 AU[13]

The velocity of the LISM (Local Interstellar Medium) relative to the Sun's was previously measured to be 26.3 km/s by Ulysses, whereas IBEX measured it at 23.2 km/s.[27]

This phenomenon has been observed outside our solar system by NASA's orbital GALEX telescope. The red giant star Mira in the constellation Cetus has been shown to have both a cometlike debris tail of ejecta from the star and a distinct bow shock preceding it in the direction of its movement through space (at over 130 kilometers per second).

Detection by spacecraft

Early planetary probes

The precise distance to, and shape of the heliopause is still uncertain. Interplanetary/interstellar spacecraft such as Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are traveling outward through the Solar System and will eventually pass through the heliopause.

- It is believed that Voyager 1 crossed the termination shock and entered the heliosheath in the middle of December 2004, at a distance of 94 AU.[28] An earlier report that this had occurred as early as August 2002 (at 85 AU) is now generally believed to have been premature.[29]

- However, Voyager 2 crossed the termination shock on August 30, 2007 at 84 AU,[30] showing evidence of denting in the heliosphere, believed to be caused by an interstellar magnetic field.[31]

Cassini results

Rather than a comet-like shape, the heliosphere appears to be bubble-shaped according to data from Cassini's Ion and Neutral Camera (MIMI / INCA). Rather than being dominated by the collisions between the solar wind and the interstellar medium, the INCA (ENA) maps suggest that the interaction is controlled more by particle pressure and magnetic field energy density.[6]

For a video of the revised no-tail model see here [1]. The new shape from the data is thought more like a spherical bubble, than a cometary shape.[6]

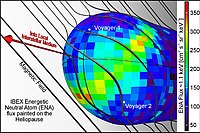

Interstellar Boundary Explorer results

Initial data from Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX), launched in October 2008, revealed a previously unpredicted "very narrow ribbon that is two to three times brighter than anything else in the sky."[7] Initial interpretations suggest that "the interstellar environment has far more influence on structuring the heliosphere than anyone previously believed"[32] "No one knows what is creating the ENA (energetic neutral atoms) ribbon, but everyone agrees that it means the textbook picture of the heliosphere—in which the Solar System's enveloping pocket filled with the solar wind's charged particles is plowing through the onrushing "galactic wind" of the interstellar medium in the shape of a comet—is wrong."[33]

"The IBEX results are truly remarkable! What we are seeing in these maps does not match with any of the previous theoretical models of this region. It will be exciting for scientists to review these (ENA) maps and revise the way we understand our heliosphere and how it interacts with the galaxy."[34]

In October 2010, significant changes were detected in the ribbon after 6 months, based on the second set of IBEX observations.[35] No bow shock was detected in 2012.[5]

Gallery of out-dated models

Depictions based on outdated scientific model as of 2009.[6][7] Issues include the heliotail and heliosheath magnetic bubble "foam".[12] In 2012, no bow shock was detected.[5]

Timeline

- Between late August and early September 2012, Voyager I has witnessed a sharp drop in protons from the sun, from 25 particles per sec in late August, to about 2 particles per second by early October.[36]

- As of June 2012 at 119 AU Voyager 1 detected an increase in cosmic rays.[10]

- As of May 2012, there is no bow shock, based on IBEX and Voyager data.[5]

- As of June 2011, the heliosheath area is thought to be filled with magnetic bubbles (each about 1 AU wide), creating a "foamy zone".[12] The theory helps explain in situ heliosphere measurements by the two Voyager probes.

- As of October 2010, significant changes were detected in the ribbon after 6 months, based on the second set of IBEX observations.[35]

- As of October 2009, the heliosphere may be bubble, not comet shaped.[6]

- As of 2008, there is a previously unpredicted narrow ribbon of ENAs.[7]

- As of March 2005, it was reported that measurements by the Solar Wind Anisotropies (SWAN) instrument onboard the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) have shown that the heliosphere, the solar wind-filled volume which prevents the Solar System from becoming embedded in the local (ambient) interstellar medium, is not axisymmetrical, but is distorted, very likely under the effect of the local galactic magnetic field.[37]

See also

Notes

- ^ The Solar Wind

- ^ Dr. David H. Hathaway (January 18, 2007). "The Solar Wind". NASA. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ a b NASA Voyager 1 Encounters New Region in Deep Space

- ^ Voyager 2 Proves Solar System Is Squashed NASA.gov #2007-12-10

- ^ a b c d e f g "New Interstellar Boundary Explorer data show heliosphere's long-theorized bow shock does not exist", Phys.org, May 10, 2012, retrieved 2012-02-11

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Johns Hopkins University (October 18, 2009). "New View Of The Heliosphere: Cassini Helps Redraw Shape Of Solar System". ScienceDaily. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

{{cite web}}: soft hyphen character in|url=at position 28 (help) - ^ a b c d e f g "First IBEX Maps Reveal Fascinating Interactions Occurring At The Edge Of The Solar System".

- ^ a b c NASA's Voyager Hits New Region at Solar System Edge 12.05.11

- ^ NASA 2011

- ^ a b c d NASA = Data From NASA's Voyager 1 Point to Interstellar Future 06.14.12

- ^ Mursula, K.; Hiltula, T., (2003). "Bashful ballerina: Southward shifted heliospheric current sheet". Geophysical Research Letters. 30 (22): 2135. Bibcode:2003GeoRL..30vSSC2M. doi:10.1029/2003GL018201.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c NASA - A Big Surprise from the Edge of the Solar System (06.09.11)

- ^ a b Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J. (June 24, 2002). "The Sun's Heliosphere & Heliopause". Astronomy Picture of the Day. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "MIT instrument finds surprises at solar system's edge". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 2007-12-10. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- ^ Than, Ker (May 24, 2006). "Voyager II detects solar system's edge". CNN. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ^ Brandt, Pontus (February 27–March 2, 2007). "Imaging of the Heliospheric Boundary" (PDF). NASA Advisory Council Workshop on Science Associated with the Lunar Exploration Architecture: White Papers. Tempe, Arizona: Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

{{cite conference}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Amos, Jonathan (December 14, 2010). "Voyager near Solar Systems edge". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- ^ a b "NASA's Voyager 1 Spacecraft Nearing Edge of the Solar System". Space.Com web site. 2010-12-13. Retrieved 2010-12-15.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Brumfiel, G. (2011-06-15). "Voyager at the edge: spacecraft finds unexpected calm at the boundary of Sun's bubble". Nature News web site. doi:10.1038/news.2011.370. Retrieved 2011-06-19.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Krimigis, S. M. (2011-06-16). "Zero outward flow velocity for plasma in a heliosheath transition layer". Nature. 474 (7351): 359–361. Bibcode:2011Natur.474..359K. doi:10.1038/nature10115. PMID 21677754. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Cook, J.-R. (2011-06-09). "NASA Probes Suggest Magnetic Bubbles Reside At Solar System Edge". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ a b c d Rayl, A. j. s. (2011-06-12). "Voyager Discovers Possible Sea of Huge, Turbulent, Magnetic Bubbles at Solar System Edge". The Planetary Society web site. The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Wood, B. E.; Alexander, W. R.; Linsky, J. L. (July 13, 2006). "The Properties of the Local Interstellar Medium and the Interaction of the Stellar Winds of \epsilon Indi and \lambda Andromedae with the Interstellar Environment". American Astronomical Society. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Steigerwald, Bill (May 24, 2005). "Voyager Enters Solar System's Final Frontier". American Astronomical Society. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ^ "Voyager 2 Proves Solar System Is Squashed". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. December 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ^ Palmer, Jason (October 15, 2009). "BBC News article". Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ No Shocks for This Bow: IBEX Says We’re Wrong

- ^ Donald A. Gurnett (1 June 2005). "Voyager Termination Shock". Department of Physics and Astronomy (University of Iowa). Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ^ Celeste Biever (25 May 2005). "Voyager 1 reaches the edge of the solar system". NewScientist. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ^ David Shiga (10 December 2007). "Voyager 2 probe reaches solar system boundary". NewScientist. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ^ Voyager 2 Proves Solar System Is Squashed NASA.gov #2007-12-10

- ^ Oct.15/09 IBEX team announcement at http://ibex.swri.edu/

- ^ Kerr, Richard A. (2009). "Tying Up the Solar System With a Ribbon of Charged Particles". Science. 326 (5951): 350–351. doi:10.1126/science.326_350a. PMID 19833930.

- ^ Dave McComas, IBEX Principal Investigator at http://ibex.swri.edu/

- ^ a b The Ever-Changing Edge of the Solar System (Oct/02/2010) - Astrobiology Magazine

- ^ NBCnews.com. "Voyager spacecraft to leave solar system". Retrieved 2012-10-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Lallement, R.; Quémerais, E.; Bertaux, J. L.; Ferron, S.; Koutroumpa, D.; Pellinen, R. (2005). "Deflection of the Interstellar Neutral Hydrogen Flow Across the Heliospheric Interface". Science. 307 (5714): 1447–1449. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1447L. doi:10.1126/science.1107953. PMID 15746421. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References for notes

- "Heliopause Seems to Be 23 Billion Kilometres". Universe Today. December 9, 2003. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- "Space probes reveal Solar System's bullet shape". COSMOS magazine. May 11, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

Further reading

- "Cassini Data Helps Redraw Shape of Our Solar System" 2010

- Publications in Refereed Journals

- Voyager Interstellar Mission Objectives

- The Heliosphere (Cosmicopia)

- NASA GALEX (Galaxy evolution Explorer) homepage at Caltech

- The Solar and Heliospheric Research Group at the University of Michigan

- Ribbon at Edge of Our Solar System: Will the Sun Enter a Million-Degree Cloud of Interstellar Gas this century ?

- A Big Surprise from the Edge of the Solar System (NASA 06.09.11)

- Schwadron, N. A. (6 September 2011). "Does the Space Environment Affect the Ecosphere?" (PDF). Eos. 92 (36). American Geophysical Union: 297–301.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Pre-2009 links

Warning, links prior to 2009 Cassini & IBEX revisions

- The Heliosphere, MIT Space Plasma Group

- UI's Don Gurnett Says Voyager 1 Is Approaching Edge Of Solar System December 8, 2003 Univ. of Iowa Press release

- NASA's Interstellar Probe (2000)

- CNN: NASA: Voyager I enters solar system's final frontier – May 25, 2005

- New Scientist: Voyager 1 reaches the edge of the solar system – May 25, 2005

- Surprises from the Edge of the Solar System – Voyager 1 Newest Findings as of September 2006

- The heliospheric hydrogen wall and astrospheres

- Heliosphere, has a diagram.

- Heliosphere Astronomy Cast episode #65, includes full transcript.