Leonardo da Vinci: Difference between revisions

| Line 237: | Line 237: | ||

* [http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/ttp/ttpbooks.html Some digitized notebook pages with explanations] from the [[British Library]] (Macromedia Shockwave format, works best for broadband users) |

* [http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/ttp/ttpbooks.html Some digitized notebook pages with explanations] from the [[British Library]] (Macromedia Shockwave format, works best for broadband users) |

||

* [http://www.elrelojdesol.com/interactive-paintings/the-last-supper.html The Last Supper (Zoomable Version)] |

* [http://www.elrelojdesol.com/interactive-paintings/the-last-supper.html The Last Supper (Zoomable Version)] |

||

* [http://davincigenius.com A celebration of the contributions of Leonardo Davinci to Western Art and Science] |

|||

* [http://www.elrelojdesol.com/interactive-paintings/mona-lisa.html Mona Lisa (Zoomable Version)] |

* [http://www.elrelojdesol.com/interactive-paintings/mona-lisa.html Mona Lisa (Zoomable Version)] |

||

* [http://www.elrelojdesol.com/leonardo-da-vinci/gallery-english/index.htm Leonardo da Vinci, Gallery of Paintings and Drawings] |

* [http://www.elrelojdesol.com/leonardo-da-vinci/gallery-english/index.htm Leonardo da Vinci, Gallery of Paintings and Drawings] |

||

| Line 277: | Line 278: | ||

[[af:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[af:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[als:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[als:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[ar: |

[[ar:???????? ?? ?????]] |

||

[[ast:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[ast:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[bn:????????? ?? ??????]] |

|||

[[bn:লিওনার্দো দা ভিঞ্চি]] |

|||

[[bs:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[bs:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[bg: |

[[bg:???????? ?? ?????]] |

||

[[ca:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[ca:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[cs:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[cs:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

| Line 288: | Line 289: | ||

[[de:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[de:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[et:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[et:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[el:????????? ??? ??????]] |

|||

[[el:Λεονάρντο ντα Βίντσι]] |

|||

[[es:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[es:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[eo:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[eo:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[eu:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[eu:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[fa: |

[[fa:???????? ???????]] |

||

[[fr: |

[[fr:L�onard de Vinci]] |

||

[[gl:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[gl:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[ko: |

[[ko:????? ? ??]] |

||

[[hr:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[hr:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[io:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[io:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

| Line 301: | Line 302: | ||

[[is:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[is:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[it:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[it:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[he: |

[[he:??????? ?? ????'?]] |

||

[[kn:????????? ? ?????]] |

|||

[[kn:ಲಿಯನಾರ್ಡೊ ಡ ವಿಂಚಿ]] |

|||

[[ka:?? ?????, ????????]] |

|||

[[ka:და ვინჩი, ლეონარდო]] |

|||

[[la:Leonardus Vincius]] |

[[la:Leonardus Vincius]] |

||

[[lb:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[lb:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[lt:Leonardas da |

[[lt:Leonardas da Vin?is]] |

||

[[hu:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[hu:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[mk: |

[[mk:???????? ?? ?????]] |

||

[[mt:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[mt:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[ms:Leonardo Da Vinci]] |

[[ms:Leonardo Da Vinci]] |

||

[[nl:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[nl:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[ja:????????????]] |

|||

[[ja:レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチ]] |

|||

[[no:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[no:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[nn:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[nn:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

| Line 319: | Line 320: | ||

[[pt:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[pt:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[ro:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[ro:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[ru: |

[[ru:?? ?????, ????????]] |

||

[[sco:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[sco:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[sq:Leonardo da |

[[sq:Leonardo da Vin�i]] |

||

[[scn:Liunardu da Vinci]] |

[[scn:Liunardu da Vinci]] |

||

[[simple:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[simple:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[sk:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[sk:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[sl:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[sl:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[sr: |

[[sr:???????? ?? ?????]] |

||

[[sh:Leonardo Da Vinci]] |

[[sh:Leonardo Da Vinci]] |

||

[[fi:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[fi:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[sv:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[sv:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[tl:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[tl:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[ta:?????????? ?? ??????]] |

|||

[[ta:லியொனார்டோ டா வின்சி]] |

|||

[[th:?????????? ?? ?????]] |

|||

[[th:เลโอนาร์โด ดา วินชี]] |

|||

[[vi:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[vi:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[tr:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

[[tr:Leonardo da Vinci]] |

||

[[uk: |

[[uk:???????? ?? ?????]] |

||

[[zh: |

[[zh:????�?�??]] |

||

Revision as of 04:26, 24 May 2006

Template:Redirect2a Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (April 15, 1452 – May 2, 1519) was an Italian Renaissance polymath: an architect, anatomist, sculptor, engineer, inventor, geometer, musician, futurist and painter. He has been described as the archetype of the "Renaissance man" and as a universal genius, a man infinitely curious and infinitely inventive. He is also considered one of the greatest painters who ever lived.

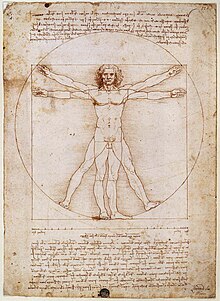

In his lifetime, Leonardo — he had no surname in the modern sense; "da Vinci" simply means "from Vinci" — was an engineer, artist, anatomist, physiologist and much more. His full birth name was "Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci", meaning "Leonardo, son of [Mes]ser Piero from Vinci". Leonardo is famous for his realistic paintings, such as the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, as well as for influential drawings such as the Vitruvian Man. He conceived of ideas vastly ahead of his own time, notably conceptually inventing the helicopter, a tank, the use of concentrated solar power, the calculator, a rudimentary theory of plate tectonics, the double hull, and others too numerous to mention. Relatively few of his designs were constructed or were feasible during his lifetime; modern scientific approaches to metallurgy and engineering were only in their infancy during the Renaissance. In addition, he greatly advanced the state of knowledge in the fields of anatomy, astronomy, civil engineering, optics, and the study of water (hydrodynamics). Of his works, only a few paintings survive, together with his notebooks (scattered among various collections) containing drawings, scientific diagrams and notes.

Early life

The first known biography of Leonardo was published in 1550 by Giorgio Vasari who wrote Vite de' piu eccelenti architettori, pittori e scultori italiani ("The lives of the most excellent Italian architects, painters and sculptors"), and later became an independent painter in Florence. Most of the information collected by Vasari was from first-hand accounts of Leonardo's contemporaries (Vasari was only a child when Leonardo died), and it remains the first reference in studying Leonardo's life.

Until recently, it was thought that Leonardo was the illegitimate son of a local peasant woman known as Caterina; now some evidence indicates that Caterina may have been a Middle Eastern Slave. His biological father appears to have been a Florentine notary or craftsman named Piero da Vinci. Leonardo's mother was married off to one Antonio di Piero del Vacca, a labourer employed by his biological father. According to papers recently found by the Museo Ideale Leonardo Da Vinci in his home town of Vinci, the marriage occurred just a few months after she gave birth to a boy called Leonardo. Even though he was born after modern naming conventions came into use, he was simply known as "Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci", which simply means "Leonardo, son of Piero, from Vinci". Leonardo signed his works "Leonardo" or "Io, Leonardo" ("I, Leonardo").

Leonardo grew up with his father Piero in Florence where he started drawing and painting. He started school when he was 5 years old. His early sketches were of such quality that his father soon showed them to the painter Andrea del Verrocchio, who subsequently took on the fourteen-year old Leonardo as an apprentice. In this role, Leonardo also worked with Lorenzo di Credi and Pietro Perugino.

- But the greatest of all Andrea's pupils was Leonardo da Vinci, in whom, besides a beauty of person never sufficiently admired and a wonderful grace in all his actions, there was such a power of intellect that whatever he turned his mind to he made himself master of with ease. [1] (Vasari)

Professional life

The earliest known dated work of Leonardo's is a drawing done in pen and ink of the Arno valley, drawn on the 5th of August, 1473. It is assumed that he had his own workshop between 1476 and 1478, receiving two orders during this time.

From around 1482 to 1499, Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan [2], employed Leonardo and permitted him to operate his own workshop, complete with apprentices. It was here that seventy tons of bronze that had been set aside for Leonardo's "Gran Cavallo" horse statue (see below) were cast into weapons for the Duke in an attempt to save Milan from the French under Charles VIII in 1495.

When the French returned under Louis XII in 1498, Milan fell without a fight, overthrowing Sforza [3]. Leonardo stayed in Milan for a time, until one morning when he found French archers using his life-size clay model of the "Gran Cavallo" for target practice. He left with Salai, his assistant and intimate, and his friend Luca Pacioli (the first man to describe double-entry bookkeeping) for Mantua, moving on after 2 months to Venice (where he was hired as a military engineer), then briefly returning to Florence at the end of April 1500.

In Florence he entered the services of Cesare Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI, acting as a military architect and engineer; with Cesare he travelled throughout Italy. In 1506 he returned to Milan, now in the hands of Maximilian Sforza after Swiss mercenaries had driven out the French.

From 1513 to 1516, he lived in Rome, where painters like Raphael and Michelangelo were active at the time, though he did not have much contact with these artists. However, he was probably of pivotal importance in the relocation of David (in Florence), one of Michelangelo's masterpieces, against the artist's will.

In 1515, Francis I of France retook Milan, and Leonardo was commissioned to make a centrepiece (a mechanical lion) for the peace talks between the French king and Pope Leo X in Bologna, where he must have first met the King. In 1516, he entered Francis' service, being given the use of the manor house Clos Lucé (also called "Cloux") next to the king's residence at the royal Chateau Amboise. The King granted Leonardo and his entourage generous pensions: the surviving document lists 1,000 écus for the artist, 400 for Count Francesco Melzi, (his pupil and one of the great loves of his life, named as "apprentice"), and 100 for Salai ("servant"). In 1518 Salai left Leonardo and returned to Milan, where he eventually perished in a duel. Francis became a close friend.

Leonardo da Vinci died at Clos Lucé, France, on 2nd May, 1519 (legend says he died in Francis's arms). According to his wish, 60 beggars followed his casket. He was buried in the Chapel of Saint-Hubert in the castle of Amboise. Although Melzi was his principal heir and executor, Salai was not forgotten; he received half of Leonardo's vineyard.

It is apparent from the works of Leonardo and his early biographers that he was a man of high integrity and very sensitive to moral issues. His respect for life led him to being a vegetarian for at least part of his life. The term "vegan" would fit him well, as he even entertained the notion that taking milk from cows amounts to stealing. Under the heading, "Of the beasts from whom cheese is made," he answers, "the milk will be taken from the tiny children." [4]. Vasari reports a story that as a young man in Florence he often bought caged birds just to release them from captivity. He was also a respected judge on matters of beauty and elegance, particularly in the creation of pageants.

Art

Leonardo pioneered new painting techniques in many of his pieces. One of them, a colour shading technique called "Chiaroscuro", used a series of glazes custom-made by Leonardo. It is characterized by subtle transitions between colour areas. Chiaroscuro is a technique of bold contrast between light and dark. Another effect created by Leonardo is called sfumato, which creates an atmospheric haze or smoky effect.

Early works in Florence (1452–1482)

Leonardo was apprenticed to the artist Verrocchio in Florence when he was about 15. In 1476 Leonardo worked with Verrocchio to paint The Baptism of Christ for the friars of Vallombrosa. He painted the angel at the front and the landscape, and the difference between the two artists' work can be seen, with Leonardo's finer blending and brushwork. Giorgio Vasari told the story that when Verrocchio saw Leonardo's work he was so amazed that he resolved never to touch a brush again.

Leonardo's first solo painting was the Madonna and Child completed in 1478; at the same time, he also painted a picture of a little boy eating sherbet. From 1480 to 1481, he created a small Annunciation painting, now in the Louvre. In 1481 he also painted an unfinished work of St. Jerome. Between 1481 and 1482 he started painting The Adoration of the Magi. He made extensive, ambitious plans and many drawings for the painting, but it was never finished, as Leonardo's services had been accepted by the Duke of Milan.

Milan (1482–1499)

Leonardo spent 17 years in Milan in the service of Duke Ludovico (between 1482 and 1499). He did many paintings, sculptures, and drawings during these many years. He also designed court festivals, and drew many of his engineering sketches. He was given free rein to work on any project he chose, though he left many projects unfinished, completing only about six paintings during this time. These include The Last Supper (Ultima Cena or Cenacolo, in Milan) in 1498 and Virgin of the Rocks in 1494. In 1499 he painted Madonna and Child with St. Anne. He worked on many of his notebooks between 1490 and 1495, including the Codex Trivulzianus.

He often planned grandiose paintings with many drawings and sketches, only to leave them unfinished. One of his projects involved making plans and models for a monumental seven-metre-high (24 ft) horse statue in bronze called "Gran Cavallo". Because of war with France, the project was never finished. (In 1999 a pair of full-scale statues based on his plans were cast, one erected in Grand Rapids, Michigan, the other in Milan [5].) The bronze intended for use in the building of the statue was used to make cannon, and victorious French soldiers used the clay model of the statue for target practice. The Hunt Museum in Limerick, Ireland has a small bronze horse thought to be the work of an apprentice from Leonardo's original design.

When the French invaded Milan in 1499, Ludovico Sforza lost control, forcing Leonardo to search for a new patron.

Nomadic Period - Italy and France (1499–1519)

Between 1499 and 1516 Leonardo worked for a number of people, travelling around Italy doing several commissions, before moving to France in 1516. This has been described as a 'Nomadic Period'. [6] He stayed in:

- Mantua (1500)

- Venice (1501)

- Florence (1501–06) known sometimes as his Second Florentine Period.

- Travelled between Florence and Milan staying in both places for short periods before settling in Milan.

- Milan (1506–13) (known sometimes as his Second Milanese Period, under the patronage of Charles d'Amboise until 1511)

- Rome (1514)

- Florence (1514)

- Pavia, Bologna, Milan (1515)

- France (1516–19) (patronage of King Francis I)

In 1500 he went to Mantua where he sketched a portrait of the Marchesa Isabella d'Este. He left for Venice in 1501, and soon after returned to Florence.

After returning to Florence, he was commissioned for a large public mural commemorating a great military triumph in the history of Florence, by the Grand Council Chamber in the Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of government of the Florentine Republic (Zollner p.164), The Battle of Anghiari; his rival Michelangelo was to paint the opposite wall The Battle of Cascina. After producing a fantastic variety of studies in preparation for the work, he left the city, with the mural unfinished due to problems with getting paid by his employer and more importantly by his choice of technique, which instead of the fresco technique he experimented again (as in the Last Supper) with oil binders hoping to extend the time to manipulate the paint (Zollner p172-178). The incomplete painting was destroyed in a war in the middle of the sixteenth century. Not only Rubens but artists in the modern era have produced their own studies based on Leonardo's original sketches..

Most evidence suggests that he began work on the Mona Lisa (also known as La Gioconda, now at the Louvre in Paris) in 1503 and continued to work on it until 1506, working sporadically on it well after that (Sasson p.22). It is likely to be Lisa de Gherardini del Giocondo, wife of a silk merchant, Francesco del Giocondo. Commissioned by her husband to commemorate the birth of their second son as well as moving to a new home (Zollner p.240). He most likely kept it with him at all times, and did not travel without it. Much is attributed to the importance of this painting, primarily why it is the most famous painting in the world. In short, it was famous at the time of its contemporaries for many different reasons than it is now. Leonardo da Vinci's use of sfumato (the smoky effect he has on his work) transcended convention of the time, as did the sitter's angle, contrapposto, and the bird's-eye view of the background. For the most part it has become famous for all of the above and for the insurmountable amount of media attention it has received. In other words, it has become famous for being famous.

He painted St Anne in 1509. Between 1506 and 1512, he lived in Milan and under the patronage of the French Governor Charles d'Amboise, he painted several other paintings. These included The Leda and the Swan, known now only through copies as the original work did not survive. He painted a second version of The Virgin of the Rocks (1506–1508). While under the patronage of Pope Leo X, he painted St. John the Baptist (1513–1516).

During his time in France, Leonardo made studies of the Virgin Mary for The Virgin and Child with St. Anne, and many drawings and other studies.

Selected works

- The Baptism of Christ (1472–1475) – Uffizi, Florence, Italy (from Verrocchio's workshop; angel on the left-hand side is generally agreed to be the earliest surviving painted work by Leonardo)

- Annunciation (1475–1480) – Uffizi, Florence, Italy

- Ginevra de' Benci (c. 1475) – National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., United States

- The Benois Madonna (1478–1480) – Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

- The Virgin with Flowers (1478–1481) – Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany

- Adoration of the Magi (1481) – Uffizi, Florence, Italy

- The Madonna of the Rocks (1483–86) – Louvre, Paris, France

- Lady with an Ermine (1488–90) – Czartoryski Museum, Krakow, Poland

- Portrait of a Musician (c. 1490) – Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan, Italy

- Madonna Litta (1490–91) – Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

- La belle Ferronière (1495–1498) – Louvre, Paris, France — attribution to Leonardo is disputed

- Last Supper (1498) – Convent of Sta. Maria delle Grazie, Milan, Italy

- The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist (c. 1499–1500) – National Gallery, London, UK

- Madonna of the Yarnwinder 1501 (original now lost)

- Mona Lisa or La Gioconda (1503-1505/1507) – Louvre, Paris, France

- The Madonna of the Rocks or The Virgin of the Rocks (1508) – National Gallery, London, UK

- Leda and the Swan (1508) - (Only copies survive — best-known example in Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy)

- The Virgin and Child with St. Anne (c. 1510) – Louvre, Paris, France

- St. John the Baptist (c. 1514) – Louvre, Paris, France

- Bacchus (or St. John in the Wilderness) (1515) – Louvre, Paris, France

Science and engineering

Renaissance humanism saw no mutually exclusive polarities between the sciences and the arts, and Leonardo's studies in science and engineering are as impressive and innovative as his artistic work, recorded in notebooks comprising some 13,000 pages of notes and drawings, which fuse art and science. These notes were made and maintained through Leonardo's travels through Europe, during which he made continual observations of the world around him. He was left-handed and used mirror writing throughout his life. This is explainable by the fact that it is easier to pull a quill pen than to push it; by using mirror-writing, the left-handed writer is able to pull the pen from right to left and also avoid smudging what has just been written. He wrote his diaries (journals) using mirror writing.

His approach to science was an observational one: he tried to understand a phenomenon by describing and depicting it in utmost detail, and did not emphasize experiments or theoretical explanation. Since he lacked formal education in Latin and mathematics, contemporary scholars mostly ignored Leonardo the scientist, although he did teach himself Latin. It has also been said that he was planning a series of treatises to be published on a variety of subjects; none ever were, though.

Anatomy

Leonardo started to discover the anatomy of the human body at the time he was apprenticed to Andrea del Verrocchio, as his teacher insisted that all his pupils learn anatomy. As he became successful as an artist, he was given permission to dissect human corpses at the hospital Santa Maria Nuova in Florence. Later he dissected in Milano at the hospital Maggiore and in Rome at the hospital Santo Spirito (the first mainland Italian hospital). From 1510 to 1511 he collaborated with the doctor Marcantonio della Torre (1481 to 1511). In 30 years, Leonardo dissected 30 male and female corpses of different ages. Together with Marcantonio, he prepared to publish a theoretical work on anatomy and made more than 200 drawings. However, his book was published only in 1580 (long after his death) under the heading Treatise on painting.

Leonardo drew many images of the human skeleton, and was the first to describe the double S form of the backbone. He also studied the inclination of pelvis and sacrum and stressed that sacrum was not uniform, but composed of five vertebrae. He was also able to represent exceptionally well the human skull and cross-sections of the brain (transversal, sagittal, and frontal). He drew many images of the lungs, mesentery, urinary tract, sex organs, and even coitus. He was one of the first who drew the fetus in the intrauterine position (he wished to learn about "the miracle of pregnancy"). He often drew muscles and tendons of the cervical muscles and of the shoulder. He was a master of topographic anatomy. He not only studied human anatomy, he studied the anatomy of many other animals, as well.

It is important to note that he was not only interested in structure but also in function, so he became a physiologist in addition to being an anatomist. He actively searched for models among those who had significant physical deformities, for the purpose of developing caricature drawings.

His study of human anatomy led also to the design of the first known robot in recorded history. The design, which has come to be called Leonardo's robot, was probably made around the year 1495 but was rediscovered only in the 1950s. It is not known if an attempt was made to build the device. He correctly worked out how heart valves eddy the flow of blood yet he was unaware of circulation as he believed that blood was pumped to the muscles where it was consumed. A diagram drawing Leonardo did of a heart inspired a British heart surgeon to pioneer a new way to repair damaged hearts in 2005. [7]

Inventions and engineering

Fascinated by the phenomenon of flight, Leonardo produced detailed studies of the flight of birds, and plans for several flying machines, including a helicopter powered by four men (which would not have worked since the body of the craft would have rotated) and a light hang glider which could have flown. [1] On January 3, 1496 he unsuccessfully tested a flying machine he had constructed.

In 1502 Leonardo da Vinci produced a drawing of a single span 720-foot (240 m) bridge as part of a civil engineering project for Sultan Beyazid II of Constantinople. The bridge was intended to span an inlet at the mouth of the Bosphorus known as the Golden Horn. Beyazid did not pursue the project, because he believed that such a construction was impossible. Leonardo's vision was resurrected in 2001 when a smaller bridge based on his design was constructed in Norway. in May 2006, the Turkish government decided to construct Leonardo's bridge. It is expected to be finished by October 2006.

Owing to his employment as a military engineer, his notebooks also contain several designs for military machines: machine guns, an armored tank powered by humans or horses, cluster bombs, a working parachute, etc. even though he later held war to be the worst of human activities. Other inventions include a submarine, a cog-wheeled device that has been interpreted as the first mechanical calculator, and a one of the first programmable robots that has been misinterpretted a car powered by a spring mechanism. In his years in the Vatican, he planned an industrial use of solar power, by employing concave mirrors to heat water. While most of Leonardo's inventions were not built during his lifetime, models of many of them have been constructed with the support of IBM and are on display at the Leonardo da Vinci Museum at the Château du Clos Lucé in Amboise[8].

His notebooks

Leonardo's notebooks were on four main themes; architecture, elements of mechanics, painting, and human anatomy. These notebooks - originally loose papers of different types and sizes, distributed by friends after his death - have found their way into major collections such as the Louvre, the Biblioteca Nacional de España, the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, and the British Library. The British Library has put a selection from its notebook (BL Arundel MS 263) on the web in the Turning the Pages section. [9] The Codex Leicester is the only major scientific work of Leonardo's in private hands. It is owned by Bill Gates, and is displayed once a year in different cities around the world.

Why Leonardo did not publish or otherwise distribute the contents of his notebooks remains a mystery to those who believe that Leonardo wanted to make his observations public knowledge (He was a perfectionist, and didn't want to share until the knowledge was presented and arranged as beautifully as possible). Technological historian Lewis Mumford suggests that Leonardo kept notebooks as a private journal, intentionally censoring his work from those who might irresponsibly use it (the tank, for instance). They remained obscure until the 19th century, and were not directly of value to the development of science and technology. In January 2005, researchers discovered the hidden laboratory used by Leonardo da Vinci for studies of flight and other pioneering scientific work in previously sealed rooms at a monastery next to the Basilica of the Santissima Annunziata, in the heart of Florence.[10]

Personal life

Leonardo kept his private life particularly secret. He claimed to have a distaste of physical relations: his comment that "the act of procreation and anything that has any relation to it is so disgusting that human beings would soon die out if there were no pretty faces and sensuous dispositions", was later interpreted by Sigmund Freud, in an analysis of the artist, as indicative of his "frigidity" (Gesammelte Werke, bd VIII, 1909–1913).

In 1476, while still living with Verrocchio, he was twice accused anonymously of sodomy with a 17 year-old model, Jacopo Saltarelli, a youth already known to the authorities for his sexual escapades with men. After two months in jail, he was acquitted, allegedly because no witnesses stepped forward, but actually on the strength of his father's respected position (Saslow, Ganymede in the Renaissance: Homosexuality in Art and Society, 1986, p.197). For some time afterwards, Leonardo and the others were kept under observation by Florence's Officers of the Night - a Renaissance organization charged with suppressing the practice of sodomy, as shown by surviving legal records of the Podestà and the Officers of the Night.

Leonardo's alleged love of boys was a topic of discussion even in the sixteenth century. In "Il Libro dei Sogni" (The Book of Dreams), a fictional dialogue on l'amore masculino (male love) written by the contemporary art critic and theorist Gian Paolo Lomazzo, Leonardo appears as one of the protagonists and declares, "Know that male love is exclusively the product of virtue which, joining men together with the diverse affections of friendship, makes it so that from a tender age they would enter into the manly one as more stalwart friends." In the dialogue, the interlocutor inquires of Leonardo about his relations with his assistant, il Salaino, "Did you play the game from behind which the Florentines love so much?" Leonardo answers, "And how many times! Keep in mind that he was a beautiful young man, especially at about fifteen."

Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno, nicknamed Salai or il Salaino ("The Little Unclean One" i.e., the devil), was described by Vasari as "a graceful and beautiful youth with fine curly hair, in which Leonardo greatly delighted." Il Salaino entered Leonardo's household in 1490 at the age of 10. The relationship was not an easy one. A year later Leonardo made a list of the boy’s misdemeanours, calling him "a thief, a liar, stubborn, and a glutton." The "Little Devil" had made off with money and valuables on at least five occasions, and spent a fortune on apparel, among which were twenty-four pairs of shoes. Nevertheless, il Salaino remained his companion, servant, and assistant for the next thirty years, and Leonardo’s notebooks during their early years contain pictures of a handsome, curly-haired adolescent.

Il Salaino's name also appears (crossed out) on the back of an erotic drawing (ca. 1513) by the artist, The Incarnate Angel, at one time in the collection of Queen Victoria. It is seen as a humorous and revealing take on his major work, St. John the Baptist, also a work and a theme imbued with homoerotic overtones by a number of art critics such as Martin Kemp and James Saslow (Saslow, ibid., passim). Another erotic work, found on the verso of a foglio in the Atlantic Codex, depicts il Salaino's behind, towards which march several penises on two legs (Augusto Marinoni, in "Io Leonardo", Mondadori, Milano 1974, pp.288, 310). Some of Leonardo's other works on erotic topics, his drawings of heterosexual human sexual intercourse, were destroyed by a priest who found them after his death.

In 1506, Leonardo met Count Francesco Melzi, the 15 year old son of a Lombard aristocrat. Melzi himself, in a letter, described Leonardo's feelings towards him as a sviscerato et ardentissimo amore ("a deeply passionate and most burning love"). (Crompton, p.269) Salai eventually accepted Melzi's continued presence and the three undertook journeys throughout Italy. Melzi became Leonardo's pupil and life companion, and is considered to have been his favourite student.

Though Salai was always introduced as Leonardo's "pupil", the artistic merit of his work has been a matter of debate. He is credited with a nude portrait of Lisa del Gioconda, known as Monna Vanna, painted in 1515 under the name of Andrea Salai.[11] The other portrait of Lisa del Gioconda, the Mona Lisa was bequeathed to Salai by Leonardo, a valuable piece even then, as it is valued in Salai's own will at £200,000.

Both of these relationships follow the pattern of eroticized apprenticeships which were frequent in the Florence of Leonardo's day, relationships which were often loving and not infrequently sexual. (See Historical pederastic couples.) Besides them, Leonardo had many other friends who are figures now renowned in their fields, or for their influence on history. These included Cesare Borgia, in whose service he spent the years of 1502 and 1503. During that time he also met Niccolò Machiavelli, with whom later he was to develop a close friendship. Also among his friends are counted Franchinus Gaffurius and Isabella d'Este, whose portrait he drew while on a journey which took him through Mantua. (Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships epigraph, p. 148 & N120 p.298)

Representations in popular culture

With the genius and legacy of Leonardo da Vinci having captivated authors and scholars generations after his death, many examples of "Da Vinci (sic) fiction" can be found in culture and literature. The most prominent example is Dan Brown's novel The Da Vinci Code (2003), which alleged that Leonardo was a member of a fictitious secret society called the Priory of Sion.

Further reading

- Jean Paul Richter (1970). The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Dover. ISBN 0486225720 and ISBN 0486225739 (paperback). 2 volumes. A reprint of the original 1883 edition.

- Frank Zollner & Johannes Nathan (2003). Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings and Drawings. Taschen. ISBN 3822817341 (hardback).

- Fred Bérence (1965). Léonard de Vinci, L'homme et son oeuvre. Somogy. Dépot légal 4° trimestre 1965.

- Charles Nicholl (2005). Leonardo da Vinci, The Flights of the mind. Penguin. ISBN 0-140-29681-6.

- Simona Cremante (2005). Leonardo da Vinci: Artist, Scientist, Inventor. Giunti. ISBN 8809038916 (hardback).

- John N. Lupia, "The Secret Revealed: How to Look at Italian Renaissance Painting," Medieval and Renaissance Times, Vol. 1, no. 2 (Summer, 1994): 6-17. (ISSN 1075–2110)

- Michael H. Hart (1992). The 100. Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 0806513500 (paperback).

- ((website)) www.runescape.com ((virtual))

See also

- Leonardo Da Vinci International Airport near Rome

- Leonardo da Vinci Art Institute, Cairo

- Luca Pacioli

- List of painters

- List of famous left-handed people

- List of Italian painters

- List of famous Italians

- Polymath

- List of polymaths

References & Notes

- ^ The U.S. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), aired in October 2005, a television programme called "Leonardo's Dream Machines", about the building and successful flight of a glider based on Leonardo's design

- History of Aerodynamics, John David Anderson, page 19. ISBN 521669553

- Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists

- Birth of Modern Science, Paolo Rossi, page 33. ISBN 631227113

- Emperor Charles V, Impresario of War, James D Tracy, page 41. ISBN 0521814316

- Algebra in Ancient and Modern Times, V S Varadarajan, page 58. ISBN 082180989X

- ArtNews article about current studies into Leonardo's life and works

- Guardian news report about evidence regarding mother's status

External links

- Vasari: Life of Leonardo: in Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. The classic vita.

- Alternative views on Leonardo da Vinci

- Leonardo da Vinci on the web page of the Italian National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo da Vinci

- Searchable version of The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci

- The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci

- Some digitized notebook pages with explanations from the British Library (Macromedia Shockwave format, works best for broadband users)

- The Last Supper (Zoomable Version)

- A celebration of the contributions of Leonardo Davinci to Western Art and Science

- Mona Lisa (Zoomable Version)

- Leonardo da Vinci, Gallery of Paintings and Drawings

- BBC Leonardo homepage

- Web Gallery of Art

- Universal Leonardo International programme of exhibitions on Leonardo (2006) and web resources

- Leonardo's 'The Last Supper and Judas'

- Leonardo da Vinci at Olga's Gallery

- A Catholic Encyclopedia entry of Leonardo

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA [[fr:L�onard de Vinci]] [[sq:Leonardo da Vin�i]] [[zh:????�?�??]]

- 1452 births

- 1519 deaths

- Anatomists

- Autodidacts

- Civil engineers

- Dynamicists

- Italian architects

- Italian inventors

- Italian scientists

- Italian sculptors

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Mathematics and culture

- Military engineers

- Natives of Tuscany

- Pederastic lovers

- People imprisoned or executed for homosexuality

- Polymaths

- Renaissance architects

- Renaissance artists

- Tuscan painters

- Vegetarians