American Revolution: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

...and I'm rehijecting this change. |

||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

The colonists did not object to the principle of contributing to the cost of their defense (colonial legislatures spent large sums raising and outfitting militias during the French and Indian War), but they disputed the need for the Crown to station regular British troops in North America. In the absence of a French threat, colonists believed the colonial militias (which were funded by taxes raised by colonial legislatures) to be sufficient to deal with any trouble with natives on the frontier. Officer positions were in high demand among the British aristocracy—the rank of captain or major sold for thousands of pounds, and could be resold once an officer purchased an even higher rank.<ref name="Shy, Toward Lexington 2008">Shy, ''Toward Lexington'' (2008) pp 69–73</ref> |

The colonists did not object to the principle of contributing to the cost of their defense (colonial legislatures spent large sums raising and outfitting militias during the French and Indian War), but they disputed the need for the Crown to station regular British troops in North America. In the absence of a French threat, colonists believed the colonial militias (which were funded by taxes raised by colonial legislatures) to be sufficient to deal with any trouble with natives on the frontier. Officer positions were in high demand among the British aristocracy—the rank of captain or major sold for thousands of pounds, and could be resold once an officer purchased an even higher rank.<ref name="Shy, Toward Lexington 2008">Shy, ''Toward Lexington'' (2008) pp 69–73</ref> |

||

The British wanted all the commissions for themselves, and were unwilling to commission colonial officers (who would pay nothing for their commissions) and further asserted that officers with colonial commissions must submit to the authority of any regular British officer, regardless of rank. This effectively negated the will or the legal authority of the colonies to contribute to defense through their militias. With some 1,500 well-connected British officers who would have become redundant in the aftermath of the Seven Years' War, London would have had to discharge them if they did not assign them to North America.<ref>Shy, ''Toward Lexington'' 73–78</ref> Therefore the main reason for Parliament imposing taxes was to prove its supremacy, and the main use of the tax funds would be patronage for ambitious British officers.<ref>Bernhard Knollenberg, ''Origin of the American Revolution: 1759–1766'' (1960) pp 76–87</ref> London responded that [[virtual representation|the colonists were "virtually represented"]]; but most Americans |

The British wanted all the commissions for themselves, and were unwilling to commission colonial officers (who would pay nothing for their commissions) and further asserted that officers with colonial commissions must submit to the authority of any regular British officer, regardless of rank. This effectively negated the will or the legal authority of the colonies to contribute to defense through their militias. With some 1,500 well-connected British officers who would have become redundant in the aftermath of the Seven Years' War, London would have had to discharge them if they did not assign them to North America.<ref>Shy, ''Toward Lexington'' 73–78</ref> Therefore the main reason for Parliament imposing taxes was to prove its supremacy, and the main use of the tax funds would be patronage for ambitious British officers.<ref>Bernhard Knollenberg, ''Origin of the American Revolution: 1759–1766'' (1960) pp 76–87</ref> London responded that [[virtual representation|the colonists were "virtually represented"]]; but most Americans rejected this.<ref>William S. Carpenter, "Taxation Without Representation" in ''Dictionary of American History, Volume 7'' (1976); Miller (1943)</ref> |

||

In 1764 Parliament enacted the [[Sugar Act]] and the [[Currency Act]], further vexing the colonists. Protests led to a powerful new weapon, the systematic [[boycott]] of British goods. The following year, the British enacted the [[Quartering Acts]], which required British soldiers to be quartered at the expense of residents in certain areas. Colonists objected to this, as well. |

In 1764 Parliament enacted the [[Sugar Act]] and the [[Currency Act]], further vexing the colonists. Protests led to a powerful new weapon, the systematic [[boycott]] of British goods. The following year, the British enacted the [[Quartering Acts]], which required British soldiers to be quartered at the expense of residents in certain areas. Colonists objected to this, as well. |

||

Revision as of 20:53, 15 April 2013

In this article, inhabitants of the Thirteen Colonies of British America that supported the American Revolution are primarily referred to as "Americans," with occasional references to "Patriots," "Whigs," "Rebels" or "Revolutionaries." Colonists who supported the British in opposing the Revolution are usually referred to as "Loyalists" or "Tories." The geographical area of the thirteen colonies is often referred to simply as "America".

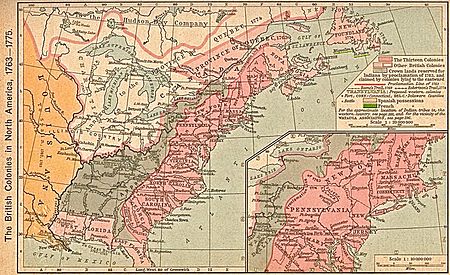

The American Revolution was a political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America. They first rejected the authority of the Parliament of Great Britain to govern them from overseas without representation, and then expelled all royal officials. By 1774 each colony had established a Provincial Congress or an equivalent governmental institution to govern itself, but still recognized the British Crown and their inclusion in the empire. The British responded by sending combat troops to re-impose direct rule. Through the Second Continental Congress, the Americans then managed the armed conflict in response to the British known as the American Revolutionary War (also: American War of Independence, 1775–83).

The British sent invasion armies and used their powerful navy to blockade the coast. George Washington became the American commander, working with Congress and the states to raise armies and neutralize the influence of Loyalists. Claiming the rule of George III of Great Britain was tyrannical and therefore illegitimate, Congress declared independence as a new nation in July 1776, when Thomas Jefferson wrote and the states unanimously ratified the United States Declaration of Independence. The British lost Boston in 1776, but then captured and held New York City. The British would capture the revolutionary capital at Philadelphia in 1777, but Congress escaped, and the British withdrew a few months later.

After a British army was captured by the American army at Saratoga, the French balanced naval power by entering the war in 1778 as allies of the United States. A combined American-French force captured a second British army at Yorktown in 1781, effectively ending the war. A peace treaty in 1783 confirmed the new nation's complete separation from the British Empire, and resulted in the United States taking possession of nearly all the territory east of the Mississippi River.

The American Revolution was the result of a series of social, political, and intellectual transformations in American society, government and ways of thinking. Americans rejected the aristocracies that dominated Europe at the time, championing instead the development of republicanism based on the Enlightenment understanding of liberalism. Virtue was the goal and corruption was the enemy. Among the significant results of the revolution was the creation of a democratically-elected representative government responsible to the will of the people. However, sharp political debates erupted over the appropriate level of democracy desirable in the new government, with a number of Founders fearing mob rule.

Fundamental issues of national governance were settled with the ratification of the United States Constitution in 1788, which replaced the weaker Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union. In contrast to the loose confederation, the Constitution established a relatively stronger federal national government. The United States Bill of Rights of 1791 is the first ten amendments to the Constitution, guaranteeing many "natural rights" that were influential in justifying the revolution, and attempted to balance a strong national government with strong state governments and broad personal liberties. The American shift to liberal republicanism, and the gradually increasing democracy, caused an upheaval of traditional social hierarchy and gave birth to the ethic that has formed a core of political values in the United States.[1][2]

Origins

The American Revolution was predicated by a number of ideas and events that, combined, led to a political and social separation of colonial possessions from the home nation and a coalescing of those former individual colonies into an independent nation.

Summary

The American revolutionary era began in 1763, after a series of victories by British forces at the conclusion of the French and Indian War ended the French military threat to British North American colonies. Adopting the policy that the colonies should contribute more to maintain the territories as part of the Empire, Britain imposed a series of direct taxes (later known as the "Stamp Act"). Americans protested vehemently at the idea that the Parliament in London could pass laws upon them, such as levying taxes, without any of their own elected representatives in the government. When tea was taxed, Bostonians dumped it, leading to harsh reprisals known as the Intolerable Acts intended to demonstrate Parliament's supremacy. Benjamin Franklin, appearing before the British Parliament testified "The Colonies raised, clothed, and paid, during the last war, near twenty-five thousand men, and spent many millions."[3]

Because the colonies lacked elected representation in the governing British Parliament, many colonists considered the new laws to be illegitimate and a violation of their rights as Englishmen. The opinion of the British Government, which was not unanimous, was that the colonies enjoyed "virtual representation".

In 1772, groups of colonists began to create Committees of Correspondence, which would lead to their own Provincial Congresses in most of the colonies. In the course of two years, the Provincial Congresses or their equivalents rejected the Parliament and effectively replaced the British ruling apparatus in the former colonies, culminating in 1774 with the coordinating First Continental Congress.[4] In response to protests in Boston over Parliament's attempts to assert authority, the British sent combat troops, shut down local government, and imposed direct rule by the army.

Consequently, the Colonies mobilized their militias, and fighting broke out in 1775. The Patriots quickly expelled royal officials from the colonies and took control. First ostensibly loyal to King George III and desiring to govern themselves while remaining in the empire, the repeated pleas by the First Continental Congress for royal intervention on their behalf with Parliament resulted in the declaration by the King that the states were "in rebellion", and the members of Congress were traitors.

In July 1776, the Second Continental Congress unanimously adopted a Declaration of Independence, which now rejected the British monarchy in addition to its Parliament, and established the sovereignty of the new nation external to the British Empire. The Declaration established the United States, which was originally governed as a loose confederation with a weak central government. (See Second Continental Congress and Congress of the Confederation.)

Ideology behind the Revolution

The ideological movement known as the American Enlightenment was a critical precursor to the American Revolution. Chief among the ideas of the American Enlightenment were the concepts of liberalism, republicanism and fear of corruption. Collectively, the acceptance of these concepts by a growing number of American colonists began to foster an intellectual environment which would lead to a new sense of political and social identity.

Natural rights and republicanism

This section may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. (January 2013) |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

John Locke's (1632–1704) ideas on liberty greatly influenced the political thinking behind the revolution, especially through his indirect influence on English writers.[clarification needed] He is often referred to as "the philosopher of the American Revolution," and is credited with leading Americans to the critical concepts of social contract, natural rights, and "born free and equal."[6] Locke's Two Treatises of Government, published in 1689, was especially influential; Locke in turn was influenced by Protestant theology.[7] He argued that, as all humans were created equally free, governments needed the consent of the governed.[8] Both Lockean concepts were central to the United States Declaration of Independence, which deduced human equality, "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" from the biblical belief in creation: "All men are created equal, ... they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.

The Declaration also referred to the "Laws of Nature and of Nature's God" as justification for the Americans' separation from the British monarchy. Most eighteenth-century Americans believed that nature, the entire universe, was God's creation. Therefore he was "Nature's God." Everything, including man, was part of the "universal order of things", which began with God and was pervaded and directed by his providence.[9] Accordingly, the signers of the Declaration professed their "firm reliance on the Protection of divine Providence." And they appealed to "the Supreme Judge [God] for the rectitude of [their] intentions." Like most of his countrymen, George Washington was firmly convinced that he was an instrument of providence, to the benefit not only of the American people but of all of humanity.[10]

The theory of the "social contract" influenced the belief among many of the Founders that among the "natural rights" of man was the right of the people to overthrow their leaders, should those leaders betray the historic rights of Englishmen.[11][12] In terms of writing state and national constitutions, the Americans heavily used Montesquieu's analysis of the wisdom of the "balanced" British Constitution.

A motivating force behind the revolution was the American embrace of a political ideology called "republicanism", which was dominant in the colonies by 1775, but of minor importance back in Britain. The republicanism was inspired by the "country party" in Britain, whose critique of British government emphasized that corruption was a terrible reality in Britain.[13] Americans feared the corruption was crossing the Atlantic; the commitment of most Americans to republican values and to their rights, energized the revolution, as Britain was increasingly seen as hopelessly corrupt and hostile to American interests. Britain seemed to threaten the established liberties that Americans enjoyed.[14] The greatest threat to liberty was depicted as corruption—not just in London but at home as well. The colonists associated it with luxury and, especially, inherited aristocracy, which they condemned.[15]

The Founding Fathers were strong advocates of republican values, particularly Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, George Washington, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton,[16] which required men to put civic duty ahead of their personal desires. Men had a civic duty to be prepared and willing to fight for the rights and liberties of their countrymen and countrywomen. John Adams, writing to Mercy Otis Warren in 1776, agreed with some classical Greek and Roman thinkers in that "Public Virtue cannot exist without private, and public Virtue is the only Foundation of Republics." He continued:

"There must be a positive Passion for the public good, the public Interest, Honour, Power, and Glory, established in the Minds of the People, or there can be no Republican Government, nor any real Liberty. And this public Passion must be Superior to all private Passions. Men must be ready, they must pride themselves, and be happy to sacrifice their private Pleasures, Passions, and Interests, nay their private Friendships and dearest connections, when they Stand in Competition with the Rights of society."[17]

For women, "republican motherhood" became the ideal, exemplified by Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren; the first duty of the republican woman was to instill republican values in her children and to avoid luxury and ostentation.

Fusing republicanism and liberalism

While some republics had emerged throughout history, such as the Roman Republic of the ancient world, one based on liberal principles had never existed. Thomas Paine's best-seller pamphlet Common Sense appeared in January 1776, after the Revolution had started. It was widely distributed and loaned, and often read aloud in taverns, contributing significantly to spreading the ideas of republicanism and liberalism together, bolstering enthusiasm for separation from Britain, and encouraging recruitment for the Continental Army.[18]

Paine provided a new and widely accepted argument for independence, by advocating a complete break with history. Common Sense is oriented to the future in a way that compels the reader to make an immediate choice. It offered a solution for Americans disgusted and alarmed at the threat of tyranny.[18]

Impact of Great Awakening

Dissenting (i.e. Protestant, non-Church of England) churches of the day were the "school of democracy."[19] President John Witherspoon of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) wrote widely circulated sermons linking the American Revolution to the teachings of the Hebrew Bible. Throughout the colonies, dissenting Protestant ministers (Congregationalist, Baptist, and Presbyterian) preached Revolutionary themes in their sermons, while most Church of England clergymen preached loyalty to the King.[20] Religious motivation for fighting tyranny reached across socioeconomic lines to encompass rich and poor, men and women, frontiersmen and townsmen, farmers and merchants.[19]

Historian Bernard Bailyn argues that the evangelism of the era challenged traditional notions of natural hierarchy by preaching that the Bible taught all men are equal, so that the true value of a man lies in his moral behavior, not his class.[21] Kidd argues that religious disestablishment, belief in a God as the guarantor of human rights, and shared convictions about sin, virtue, and divine providence worked together to unite rationalists and evangelicals and thus encouraged American defiance of the Empire.[22]

Emphasizing the intense opposition to sending an Anglican bishop to the colonies, and the Quebec Act of 1774 fomenting public anger by perception of being too pro-Catholic, Kidd argues that the reactions reflected the long-term influence of the Great Awakening, in terms of apocalyptic warnings, religious egalitarianism, and anti‐Catholicism. He said that the result was that by 1773, when British challenges to American's perceptions of their rights as Englishmen escalated, Patriots were prepared to defy British administrators.[22]

Controversial British legislation

The Revolution was in some ways incited by a number of pieces of legislation originating from the British Parliament that, for Americans, were illegitimate acts of a government that had no right to pass laws on Englishmen in the Americas who did not have elected representation in that government. For the British, policy makers saw these laws as necessary to rein in colonial subjects who, in the name of economic development that was designed to benefit the home nation, had been allowed near-autonomy for too long.

1733–1763: Navigation Acts, Molasses Act and Royal Proclamation

The British Empire at the time operated under the mercantile system, where all trade was concentrated inside the Empire, and trade with other empires was forbidden. The goal was to enrich Britain—its merchants and its government. Whether the policy was good for the colonists was not an issue in London, but Americans became increasingly restive with mercantilist policies[23]

Britain implemented mercantilism by trying to block American trade with the French, Spanish or Dutch empires using the Navigation Acts, which Americans avoided as often as they could. The royal officials responded to smuggling with open-ended search warrants (Writs of Assistance). In 1761, Boston lawyer James Otis argued that the writs violated the constitutional rights of the colonists. He lost the case, but John Adams later wrote, "Then and there the child Independence was born."[24]

In 1762, Patrick Henry argued the Parson's Cause in the Colony of Virginia, where the legislature had passed a law and it was vetoed by the king. Henry argued, "that a King, by disallowing Acts of this salutary nature, from being the father of his people, degenerated into a Tyrant and forfeits all right to his subjects' obedience".[25]

Following their victory in the French and Indian War in 1763, Great Britain took control of the French holdings in North America, outside the Caribbean. The British sought to maintain peaceful relations with those Indian tribes that had allied with the French, and keep them separated from the American frontiersmen. To this end, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 restricted settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains as this was designated an Indian Reserve.[26] Disregarding the proclamation, some groups of settlers continued to move west and establish farms.[27] The proclamation was soon modified and was no longer a hindrance to settlement, but the fact that it had been promulgated without their prior consultation angered the colonists.[28]

1764–1766: More provocative legislation

Britain did not expect the colonies to contribute to the interest or the retirement of debt incurred during its wars, but they did expect a portion of the expenses for colonial defense to be paid by the Americans. Estimating the expenses of defending the continental colonies and the British West Indies to be approximately £200,000 annually, the British goal after the end of this war was that the colonies would be taxed for £78,000 of this amount. The colonists objected chiefly on the grounds not that the taxes were high (they were low)[29] but that they had no representation in the Parliament. Benjamin Franklin testified in Parliament that Americans already contributed heavily to the defense of their portion of the Empire, the local governments raising, clothing and paying nearly twenty-five thousand men, and spending many millions from American treasuries doing so in the French and Indian War alone.[3] Parliament insisted it had the right to levy any tax without colonial approval, to demonstrate that it had authority over the colonies.[30]

Modern American economic historians have challenged the view that Britain was seeking to place a heavy new burden on the colonies and have suggested the real cost of defending the North American colonies from the possibility of invasion by France or Spain was £400,000, five times the maximum income from them.[31] On the other hand, the colonists felt the heavy military presence as an unwelcome burden in other ways besides taxation. Perhaps, most notably, the British military was determined to carry on with requisitioning practices in the colonies in much the same way they had during the French and Indian War. This did not require any specific Parliamentary sanction – established law permitted commanders to acquire goods and livestock from local suppliers at prices the military deemed to be fair, but what had been an understandable and tolerated arrangement during wartime quickly became a serious irritant in the colonies once the hostilities with France were over.

The colonists did not object to the principle of contributing to the cost of their defense (colonial legislatures spent large sums raising and outfitting militias during the French and Indian War), but they disputed the need for the Crown to station regular British troops in North America. In the absence of a French threat, colonists believed the colonial militias (which were funded by taxes raised by colonial legislatures) to be sufficient to deal with any trouble with natives on the frontier. Officer positions were in high demand among the British aristocracy—the rank of captain or major sold for thousands of pounds, and could be resold once an officer purchased an even higher rank.[32]

The British wanted all the commissions for themselves, and were unwilling to commission colonial officers (who would pay nothing for their commissions) and further asserted that officers with colonial commissions must submit to the authority of any regular British officer, regardless of rank. This effectively negated the will or the legal authority of the colonies to contribute to defense through their militias. With some 1,500 well-connected British officers who would have become redundant in the aftermath of the Seven Years' War, London would have had to discharge them if they did not assign them to North America.[33] Therefore the main reason for Parliament imposing taxes was to prove its supremacy, and the main use of the tax funds would be patronage for ambitious British officers.[34] London responded that the colonists were "virtually represented"; but most Americans rejected this.[35]

In 1764 Parliament enacted the Sugar Act and the Currency Act, further vexing the colonists. Protests led to a powerful new weapon, the systematic boycott of British goods. The following year, the British enacted the Quartering Acts, which required British soldiers to be quartered at the expense of residents in certain areas. Colonists objected to this, as well.

In 1765 the Stamp Act was the first direct tax levied on the colonies by British Prime Minister George Grenville and the Parliament. All official documents, newspapers, almanacs, and pamphlets— decks of playing cards—were required to have the stamps. The colonists still considered themselves loyal subjects of the British Crown, with the same historic rights and obligations as subjects in Britain.[36] Nevertheless, representatives of all 13 colonies protested vehemently, as popular leaders such as Patrick Henry in Virginia and James Otis in Massachusetts, rallied the people in opposition. A secret group, the "Sons of Liberty" formed in many towns and threatened violence if anyone sold the stamps, and no one did.[37]

In Boston, the Sons of Liberty burned the records of the vice-admiralty court and looted the home of the chief justice, Thomas Hutchinson. Several legislatures called for united action, and nine colonies sent delegates to the Stamp Act Congress in New York City in October 1765. Moderates led by John Dickinson drew up a "Declaration of Rights and Grievances" stating that taxes passed without representation violated their Rights of Englishmen. Colonists emphasized their determination by boycotting imports of British merchandise.[25]

In London, the Rockingham government came to power and Parliament debated whether to repeal the stamp tax or send an army to enforce it. Benjamin Franklin made the case for repeal, explaining the colonies had spent heavily in manpower, money, and blood in defense of the empire in a series of wars against the French and Indians, and that further taxes to pay for those wars were unjust and might bring about a rebellion. Parliament agreed and repealed the tax, but in the Declaratory Act of March 1766 insisted that parliament retained full power to make laws for the colonies "in all cases whatsoever".[25]

1767–1773: Townshend Acts and the Tea Act

In 1767 the Parliament passed the Townshend Acts, which placed a tax on a number of essential goods including paper, glass, and tea. Angered at the tax increases, colonists organized a boycott of British goods. In Boston on March 5, 1770 a large mob gathered around a group of British soldiers. The mob grew more and more threatening, throwing snowballs, rocks and debris at the soldiers. One soldier was clubbed and fell.[38]

All but one of the soldiers fired into the crowd. 11 people were hit; three civilians were killed at the scene of the shooting, and two died after the incident. The event quickly came to be called the Boston Massacre. Although the soldiers were tried and acquitted (defended by John Adams), the widespread descriptions soon became propaganda to turn colonial sentiment against the British. This in turn began a downward spiral in the relationship between Britain and the Province of Massachusetts.[38]

In June 1772, in what became known as the Gaspée Affair, a British warship that had been vigorously enforcing unpopular trade regulations was burned by American patriots including John Brown. About a year later, private letters were published in which Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson called for the abridgement of colonial rights, and Lieutenant Governor Andrew Oliver called for the direct payment of colonial officials (until then the purview of the colonial assembly, and a means by which it controlled the governor). The furor over the affair contributed to Hutchinson's recall, and brought a conciliatory Benjamin Franklin firmly to the side of the colonists.

On December 16, 1773 a group of men, led by Samuel Adams and dressed to evoke American Indians, boarded the ships of the government-favored British East India Company and dumped an estimated £10,000 worth of tea from its holds (approximately £636,000 in 2008) into Boston Harbor. This event became known as the Boston Tea Party and remains a significant part of American patriotic lore.[40]

1774–1775: Quebec Act and the Intolerable Acts

The Quebec Act of 1774 extended Quebec's boundaries to the Ohio River, shutting out the claims of the 13 colonies. By then, however, the Americans had little regard for new laws from London; they were drilling militia and organizing for war.[41]

The British government responded by passing several Acts which came to be known as the Intolerable Acts, which further darkened colonial opinion towards the British. They consisted of four laws enacted by the British parliament.[42] The first was the Massachusetts Government Act, which altered the Massachusetts charter and restricted town meetings. The second Act, the Administration of Justice Act, ordered that all British soldiers to be tried were to be arraigned in Britain, not in the colonies.

The third Act was the Boston Port Act, which closed the port of Boston until the British had been compensated for the tea lost in the Boston Tea Party (the British never received such a payment). The fourth Act was the Quartering Acts of 1774, which allowed royal governors to house British troops in the homes of citizens without requiring permission of the owner.

Lord North argued in 1775 for the British position that Englishmen paid on average 25 shillings annually in taxes whereas Americans paid only sixpence.[43] The colonists countered that North's argument failed to take into consideration the taxes collected by colonial governments and allocated for local purposes. The colonists believed, especially considering the economic restraints the British were keen to enforce in the colonies, that any additional tax burden from London was excessive.

American political opposition

American political opposition was initially through the colonial assemblies such as the Stamp Act Congress, which included representatives from across the colonies. In 1765 the Sons of Liberty were formed which used public demonstrations, violence and threats of violence to ensure that the British tax laws were unenforceable. While openly hostile to what they considered an oppressive Parliament acting illegally, colonists persisted in sending numerous petitions and pleas for intervention from a monarch to whom they still claimed loyalty. In late 1772 Samuel Adams in Boston set about creating new Committees of Correspondence, which linked Patriots in all 13 colonies and eventually provided the framework for a rebel government. In early 1773 Virginia, the largest colony, set up its Committee of Correspondence, on which Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson served.[44]

A total of about 7000 to 8000 Patriots served on "Committees of Correspondence" at the colonial and local levels, comprising most of the leadership in their communities—the Loyalists were excluded. The committees became the leaders of the American resistance to British actions, and largely determined the war effort at the state and local level. When the First Continental Congress decided to boycott British products, the colonial and local Committees took charge, examining merchant records and publishing the names of merchants who attempted to defy the boycott by importing British goods.[45]

They promoted patriotism and home manufacturing, advising Americans to avoid luxuries and lead more simple lives. The committees gradually extended their power over many aspects of American public life. They set up espionage networks to identify disloyal elements, displaced the royal officials, and helped topple the entire imperial system in each colony. In late 1774 in early 1775, they supervised the elections of provincial conventions, which took over the operation of colonial governments.[45]

In response to the Massachusetts Government Act, Massachusetts and other colonies formed local governments called Provincial Congresses. In 1774, the First Continental Congress convened, consisting of representatives from each of the Provincial Congresses or their equivalents, to serve as a vehicle for deliberation and collective action. Standing "Committees of Safety" were created by each Provincial Congress or equivalent for the enforcement of resolutions by the Committees of Correspondence, Provincial Congress, and the Continental Congress. Some British colonies in North America remained loyal to the Crown. These colonies included Quebec, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland in present-day Canada, the former Spanish colonies of West Florida and East Florida, and Bermuda.

Factions

The population of the 13 Colonies was far from homogeneous, particularly in their political views and attitudes. Loyalties and allegiances varied widely not only within regions and communities, but also within families and sometimes shifted during the course of the Revolution.

Class and psychology of the factions

Looking back, John Adams concluded in 1818:

- "The Revolution was effected before the war commenced. The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people ... This radical change in the principles, opinions, sentiments, and affections of the people was the real American Revolution."[46]

In terms of class, Loyalists tended to have longstanding social and economic connections to British merchants and government; for instance, prominent merchants in major port cities such as New York, Boston and Charleston tended to be Loyalists, as did men involved with the fur trade along the northern frontier.[citation needed] In addition, officials of colonial government and their staffs, those who had established positions and status to maintain, favored maintaining relations with Great Britain. They often were linked to British families in England by marriage as well.[citation needed]

By contrast, Patriots by number tended to be yeomen farmers, especially in the frontier areas of New York and the backcountry of Pennsylvania, Virginia and down the Appalachian mountains.[citation needed] They were craftsmen and small merchants. Leaders of both the Patriots and the Loyalists were men of educated, propertied classes. The Patriots included many prominent men of the planter class from Virginia and South Carolina, for instance, who became leaders during the Revolution, and formed the new government at the national and state levels.[citation needed]

To understand the opposing groups, historians have assessed evidence of their hearts and minds. In the mid-20th century, historian Leonard Woods Labaree identified eight characteristics of the Loyalists that made them essentially conservative; traits to those characteristic of the Patriots.[47] Older and better established men, Loyalists tended to resist innovation. They thought resistance to the Crown—which they insisted was the only legitimate government—was morally wrong, while the Patriots thought morality was on their side.[48][49]

Loyalists were alienated when the Patriots resorted to violence, such as burning houses and tarring and feathering. Loyalists wanted to take a centrist position and resisted the Patriots' demand to declare their opposition to the Crown. Many Loyalists, especially merchants in the port cities, had maintained strong and long-standing relations with Britain (often with business and family links to other parts of the British Empire).[48][49]

Many Loyalists realized that independence was bound to come eventually, but they were fearful that revolution might lead to anarchy, tyranny or mob rule. In contrast, the prevailing attitude among Patriots, who made systematic efforts to use mob violence in a controlled manner, was a desire to seize the initiative.[48][49] Labaree also wrote that Loyalists were pessimists who lacked the confidence in the future displayed by the Patriots.[47]

Historians in the early 20th century, such as J. Franklin Jameson, examined the class composition of the Patriot cause, looking for evidence of a class war inside the revolution.[50] In the last 50 years, historians have largely abandoned that interpretation, emphasizing instead the high level of ideological unity.[51] Just as there were rich and poor Loyalists, the Patriots were a 'mixed lot', with the richer and better educated more likely to become officers in the Army.[52][53]

Ideological demands always came first: the Patriots viewed independence as a means to gain freedom from British oppression and taxation and, above all, to reassert what they considered to be their rights as English subjects. Most yeomen farmers, craftsmen, and small merchants joined the Patriot cause to demand more political equality. They were especially successful in the Pennsylvania but less so in New England, where John Adams attacked Thomas Paine's Common Sense for the "absurd democratical notions" it proposed.[52][53]

King George III

The war became a personal issue for the king, fueled by his growing belief that British leniency would be taken as weakness by the Americans. The king also sincerely believed he was defending Britain's constitution against usurpers, rather than opposing patriots fighting for their natural rights.[54]

Patriots

At the time, revolutionaries were called "Patriots", "Whigs", "Congress-men", or "Americans". They included a full range of social and economic classes, but were unanimous regarding the need to defend the rights of Americans and uphold the principles of republicanism in terms of rejecting monarchy and aristocracy, while emphasizing civic virtue on the part of the citizens.

Mark Lender explores why ordinary folk became insurgents against the British even though they were unfamiliar with the ideological rationales being offered. They held very strongly a sense of ”rights” that they felt British were violating – rights that stressed local autonomy, fair dealing, and government by consent. They were highly sensitive to the issue of tyranny, which they saw manifested in the British response to the Boston Tea Party. The arrival in Boston of the British Army heightened their sense of violated rights, leading to rage and demands for revenge. They had faith that God was on their side.[55]

Loyalists

While there is no way of knowing the numbers, historians have estimated that about 15–20% of the population remained loyal to the British Crown; these were known at the time as "Loyalists", "Tories", or "King's men". The Loyalists never controlled territory unless the British Army occupied it.[56] Loyalists were typically older, less willing to break with old loyalties, often connected to the Church of England, and included many established merchants with strong business connections across the Empire, as well as royal officials such as Thomas Hutchinson of Boston.[56]

The revolution sometimes divided families; for example, the Franklins. William Franklin, son of Benjamin Franklin and governor of the Province of New Jersey, remained Loyal to the Crown throughout the war; he never spoke to his father again. Recent immigrants who had not been fully Americanized were also inclined to support the King, such as recent Scottish settlers in the back country; among the more striking examples of this, see Flora MacDonald.[56]

After the war, the great majority of the 450,000–500,000 Loyalists remained in America and resumed normal lives. Some, such as Samuel Seabury, became prominent American leaders. Estimates vary, but about 62,000 Loyalists relocated to Canada, and others to Britain (7,000) or to Florida or the West Indies (9,000). The exiles represented approximately 2% of the total population of the colonies.[57]

When Loyalists left the South in 1783, they took thousands of their slaves with them to the British West Indies.[57] Before that, tens of thousands of slaves had escaped, disrupting agriculture particularly in South Carolina and Georgia. The British freed slaves of rebels who joined them.

Neutrals

A minority of uncertain size tried to stay neutral in the war. Most kept a low profile, but the Quakers, especially in Pennsylvania, were the most important group to speak out for neutrality. As Patriots declared independence, the Quakers, who continued to do business with the British, were attacked as supporters of British rule, "contrivers and authors of seditious publications" critical of the revolutionary cause.[58]

Role of women

Women contributed to the American Revolution in many ways, and were involved on both sides. While formal Revolutionary politics did not include women, ordinary domestic behaviors became charged with political significance as Patriot women confronted a war that permeated all aspects of political, civil, and domestic life. They participated by boycotting British goods, spying on the British, following armies as they marched, washing, cooking, and tending for soldiers, delivering secret messages, and in a few cases like Deborah Samson, fighting disguised as men. Also, Mercy Otis Warren held meetings in her house and cleverly attacked Loyalists with her creative plays and histories.[59] Above all, they continued the agricultural work at home to feed their families and the armies. They maintained their families during their husbands' absences and sometimes after their deaths.[60]

American women were integral to the success of the boycott of British goods,[61] as the boycotted items were largely household items such as tea and cloth. Women had to return to knitting goods, and to spinning and weaving their own cloth — skills that had fallen into disuse. In 1769, the women of Boston produced 40,000 skeins of yarn, and 180 women in Middletown, Massachusetts wove 20,522 yards (18,765 m) of cloth.[60]

A crisis of political loyalties could disrupt the fabric of colonial America women's social worlds: whether a man did or did not renounce his allegiance to the King could dissolve ties of class, family, and friendship, isolating women from former connections. A woman's loyalty to her husband, once a private commitment, could become a political act, especially for women in America committed to men who remained loyal to the King. Legal divorce, usually rare, was granted to Patriot women whose husbands supported the King.[62][63]

Other participants

France

In early 1776, France set up a major program of aid to the Americans, and the Spanish secretly added funds. Each country spent one million "livres tournaises" to buy munitions. A dummy corporation run by Pierre Beaumarchais concealed their activities. American rebels obtained some munitions through the Dutch Republic as well as French and Spanish ports in the West Indies.[64]

Spain

Spain did not officially recognize the U.S. but became an informal ally when it declared war on Britain on June 21, 1779. Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, general of the Spanish forces in New Spain, also served as governor of Louisiana. He led an expedition of colonial troops to force the British out of Florida and keep open a vital conduit for supplies.[65]

Native Americans

Most Native Americans rejected pleas that they remain neutral and supported the British Crown, both because of trading relationships and its efforts to prohibit colonial settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains. The great majority of the 200,000 Native Americans east of the Mississippi distrusted the colonists and supported the British cause, hoping to forestall continued colonial encroachment on their territories.[66] Those tribes that were more closely involved in colonial trade tended to side with the revolutionaries, although political factors were important as well.

Although there was limited participation by Native American warriors except for those associated with four of the Iroquois nations in New York and Pennsylvania, the British provided Indians with funding and weapons to attack American outposts. Some Indians tried to remain neutral, seeing little value in joining a European conflict and fearing reprisals from whichever side they opposed. The Oneida and Tuscarora peoples of western New York supported the American cause.[67]

The British provided arms to Indians, who were led by Loyalists in war parties to raid frontier settlements from the Carolinas to New York. They killed many scattered settlers, especially in Pennsylvania. In 1776 Cherokee war parties attacked American colonists all along the southern frontier of the uplands.[68] While the Chickamauga Cherokee could launch raids numbering a couple hundred warriors, as seen in the Chickamauga Wars, they could not mobilize enough forces to fight a major invasion without the help of allies, most often the Creek.

Joseph Brant of the powerful Mohawk nation, part of the Iroquois Confederacy based in New York, was the most prominent Native American leader against the rebel forces. In 1778 and 1780, he led 300 Iroquois warriors and 100 white Loyalists in multiple attacks on small frontier settlements in New York and Pennsylvania, killing many settlers and destroying villages, crops and stores.[69] The Seneca, Onondaga and Cayuga of the Iroquois Confederacy also allied with the British against the Americans.[70]

In 1779 the Continentals retaliated with an American army under John Sullivan, which raided and destroyed 40 empty Iroquois villages in central and western New York.[70] Sullivan's forces systematically burned the villages and destroyed about 160,000 bushels of corn that comprised the winter food supply. Facing starvation and homeless for the winter, the Iroquois fled to the Niagara Falls area and to Canada, mostly to what became Ontario. The British resettled them there after the war, providing land grants as compensation for some of their losses.[71]

At the peace conference following the war, the British ceded lands which they did not really control, and did not consult their Indian allies. They "transferred" control to the Americans of all the land east of the Mississippi and north of Florida. The historian Calloway concludes:

- Burned villages and crops, murdered chiefs, divided councils and civil wars, migrations, towns and forts choked with refugees, economic disruption, breaking of ancient traditions, losses in battle and to disease and hunger, betrayal to their enemies, all made the American Revolution one of the darkest periods in American Indian history.[72]

The British did not give up their forts in the West (what is now the Ohio to Wisconsin) until 1796; they kept alive the dream of forming a satellite Indian nation there, which they called a Neutral Indian Zone. That goal was one of the causes of the War of 1812.[73][74]

African Americans

Free blacks in the North and South fought on both sides of the Revolution, but most fought for the colonial rebels.[citation needed] Crispus Attucks, who died in a conflict in Boston in 1770, is considered the first martyr of the American Revolution. Both sides offered freedom and re-settlement to slaves who were willing to fight for them, especially targeting slaves whose owners supported the opposing cause.

Many African-American slaves became politically active during these years in support of the King, as they thought Great Britain might abolish slavery in the colonies. Tens of thousands used the turmoil of war to escape, and the southern plantation economies of South Carolina and Georgia especially were disrupted. During the Revolution, the British tried to turn slavery against the Americans,[75] but historian David Brion Davis explains the difficulties with a policy of wholesale arming of the slaves:

But England greatly feared the effects of any such move on its own West Indies, where Americans had already aroused alarm over a possible threat to incite slave insurrections. The British elites also understood that an all-out attack on one form of property could easily lead to an assault on all boundaries of privilege and social order, as envisioned by radical religious sects in Britain's seventeenth-century civil wars.[76]

Davis underscored the British dilemma: "Britain, when confronted by the rebellious American colonists, hoped to exploit their fear of slave revolts while also reassuring the large number of slave-holding Loyalists and wealthy Caribbean planters and merchants that their slave property would be secure".[77] The colonists accused the British of encouraging slave revolts.[78]

American advocates of independence were commonly lampooned in Britain for what was termed their hypocritical calls for freedom, at the same time that many of their leaders were planters who held hundreds of slaves. Samuel Johnson snapped, "how is it we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the [slave] drivers of the Negroes?"[79] Benjamin Franklin countered by criticizing the British self-congratulation about "the freeing of one Negro" (Somersett) while they continued to permit the Slave Trade.[80]

Phyllis Wheatley, a black poet who popularized the image of Columbia to represent America, came to public attention when her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral appeared in 1773.[81]

During the war, slaves escaped from across New England and the mid-Atlantic area to British-occupied cities, such as New York. The effects of the war were more dramatic in the South. In Virginia the royal governor Lord Dunmore recruited black men into the British forces with the promise of freedom, protection for their families, and land grants. Tens of thousands of slaves escaped to British lines throughout the South, causing dramatic losses to slaveholders and disrupting cultivation and harvesting of crops. For instance, South Carolina was estimated to lose about 25,000 slaves, or one third of its slave population, to flight, migration or death. From 1770 to 1790, the black proportion of the population (mostly slaves) in South Carolina dropped from 60.5 percent to 43.8 percent; and in Georgia from 45.2 percent to 36.1 percent.[82]

When the British evacuated its forces from Savannah and Charleston, it also gave transportation to 10,000 slaves, carrying through on its commitment to them.[83] They evacuated and resettled more than 3,000 "Black Loyalists" from New York to Nova Scotia, Upper and Lower Canada. Others sailed with the British to England or were resettled in the West Indies of the Caribbean. More than 1200 of the Black Loyalists of Nova Scotia later resettled in the British colony of Sierra Leone, where they became leaders of the Krio ethnic group of Freetown and the later national government. Many of their descendants still live in Sierra Leone, as well as other African countries.[84]

Some slaves understood Revolutionary rhetoric as promising freedom and equality. Both British and American governments made promises of freedom for service, and many slaves fought in one army or the other. Starting in 1777, northern states started to abolish slavery, beginning with Vermont, which ended it under its new state constitution. By court cases, Massachusetts effectively ended slavery before the end of the century. Usually states instituted abolition on a gradual schedule with no government compensation of the owners, and many states, such as New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, required long apprenticeships of former slave children before they gained freedom and came of age as adults.

In the first two decades after the war, the legislatures of Virginia, Maryland and Delaware made it easier for slaveholders to manumit their slaves.[85] Numerous slaveholders in the Upper South took advantage of the changes: the proportion of free blacks went from less than one percent before the war to more than 10 percent overall by 1810.[86] In Virginia alone, the number of free blacks climbed: from less than one percent in 1782, to 4.2 percent in 1790, and 13.5 percent in 1810.[86] In Delaware, three-quarters of blacks were free by 1810.[87]

After this time, few slaves were freed in the South, except those who were favorites or the master's children. The demand for slaves rose with the growth of cotton as a commodity crop, especially after the invention of the cotton gin, which enabled the widespread cultivation of short-staple cotton in the upland regions. Although the international slave trade was prohibited, the slave population in the United States increased by the formation of families and survival of children throughout the South. As the demand for slave labor in the Upper South decreased due to changes in crops, planters began selling their slaves to traders and markets to the Deep South in an internal slave trade; it would cause the forced migration of an estimated one million slaves during the following decades, breaking up countless families, as young males were most in demand.

Military hostilities begin

The Battle of Lexington and Concord took place April 19, 1775, when the British sent a force of roughly 1000 troops to confiscate arms and arrest revolutionaries in Concord, Massachusetts.[88] They clashed with the local militia, marking the first fighting of the American Revolutionary War. The news aroused the 13 colonies to call out their militias and send troops to besiege Boston. The Battle of Bunker Hill followed on June 17, 1775. While a British victory, it was at a great cost; about 1,000 British casualties from a garrison of about 6,000, as compared to 500 American casualties from a much larger force.[89][90]

The Second Continental Congress convened in 1775, after the war had started. The Congress created the Continental Army and extended the Olive Branch Petition to the crown as an attempt at reconciliation. King George III refused to receive it, issuing instead the Proclamation of Rebellion, requiring action against the "traitors".

In the winter of 1775, the Americans invaded Canada. General Richard Montgomery captured Montreal but a joint attack on Quebec with the help of Benedict Arnold failed.

In March 1776, with George Washington as the commander of the new army, the Continental Army forced the British to evacuate Boston. The revolutionaries were now in full control of all 13 colonies and were ready to declare independence. While there still were many Loyalists, they were no longer in control anywhere by July 1776, and all of the Royal officials had fled.[91]

Prisoners

In August 1775, George III declared Americans in arms against royal authority to be traitors to the Crown. Although Lord Germain took a hard line the British generals on the scene never held treason trials; they treated captured soldiers as prisoners of war.[92] The dilemma was that tens of thousands of Loyalists were under American control and American retaliation would have been easy. The British built much of their strategy around using these Loyalists.[93]

After the surrender at Saratoga in October 1777, furthermore, there were thousands of British and Hessian soldiers in American hands. Therefore no Americans were put on trial for treason. The British maltreated the prisoners they held, resulting in more deaths to American sailors and soldiers than combat operations.[93] At the end of the war, both sides released their surviving prisoners.[94]

Finance

Britain's war against the Americans, French and Spanish cost about £100 million. The Treasury borrowed 40% of the money it needed.[95] Heavy spending brought France to the verge of bankruptcy and revolution, while the British had relatively little difficulty financing their war, keeping their suppliers and soldiers paid, and hiring tens of thousands of German soldiers.[96]

Britain had a sophisticated financial system based on the wealth of thousands of landowners, who supported the government, together with banks and financiers in London. The efficient British tax system collected about 12 percent of the GDP in taxes during the 1770s.[96]

In sharp contrast, Congress and the American states had no end of difficulty financing the war.[97] In 1775 there was at most 12 million dollars in gold in the colonies, not nearly enough to cover current transactions, let alone on a major war. The British made the situation much worse by imposing a tight blockade on every American port, which cut off almost all imports and exports. One partial solution was to rely on volunteer support from militiamen, and donations from patriotic citizens.[98]

Another was to delay actual payments, pay soldiers and suppliers in depreciated currency, and promise it would be made good after the war. Indeed, in 1783 the soldiers and officers were given land grants to cover the wages they had earned but had not been paid during the war. Not until 1781, when Robert Morris was named Superintendent of Finance of the United States, did the national government have a strong leader in financial matters.[98]

Morris used a French loan in 1782 to set up the private Bank of North America to finance the war. Seeking greater efficiency, Morris reduced the civil list, saved money by using competitive bidding for contracts, tightened accounting procedures, and demanded the national government's full share of money and supplies from the confederated states.[98]

Congress used four main methods to cover the cost of the war, which cost about 66 million dollars in specie (gold and silver).[99] Congress made two issues of paper money, in 1775–1780, and in 1780–81. The first issue amounted to 242 million dollars. This paper money would supposedly be redeemed for state taxes,[citation needed] but the holders were eventually paid off in 1791 at the rate of one cent on the dollar.[citation needed] By 1780, the paper money was "not worth a Continental", as people said, and a second issue of new currency was attempted.[clarification needed]

The second issue quickly became nearly worthless—but it was redeemed by the new federal government in 1791 at 100 cents on the dollar.[citation needed] At the same time the states, especially Virginia and the Carolinas, issued over 200 million dollars of their own currency.[citation needed] In effect, the paper money was a hidden tax on the people, and indeed was the only method of taxation that was possible at the time.[citation needed][clarification needed]

The skyrocketing inflation was a hardship on the few people who had fixed incomes—but 90 percent of the people were farmers, and were not directly affected by that inflation. Debtors benefited by paying off their debts with depreciated paper.[100] The greatest burden was borne by the soldiers of the Continental Army, whose wages—usually in arrears—declined in value every month, weakening their morale and adding to the hardships suffered by their families.[citation needed]

Beginning in 1777, Congress repeatedly asked the states to provide money. But the states had no system of taxation either, and were little help. By 1780 Congress was making requisitions for specific supplies of corn, beef, pork and other necessities—an inefficient system that kept the army barely alive.[101][102]

Starting in 1776, the Congress sought to raise money by loans from wealthy individuals, promising to redeem the bonds after the war. The bonds were in fact redeemed in 1791 at face value, but the scheme raised little money because Americans had little specie, and many of the rich merchants were supporters of the Crown.[citation needed] Starting in 1776, the French secretly supplied the Americans with money, gunpowder, and munitions in order to weaken its arch enemy, Great Britain. When France officially entered the war in 1778, the subsidies continued, and the French government, as well as bankers in Paris and Amsterdam loaned large sums to the American war effort. These loans were repaid in full in the 1790s.[103]

Creating new state constitutions

Following the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775, the Patriots had control of most of Massachusetts; the Loyalists suddenly found themselves on the defensive. In all 13 colonies, Patriots had overthrown their existing governments, closing courts and driving British governors, agents and supporters from their homes. They had elected conventions and "legislatures" that existed outside of any legal framework; new constitutions were used in each state to supersede royal charters. They declared they were states now, not colonies.[104]

On January 5, 1776, New Hampshire ratified the first state constitution, six months before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Then, in May 1776, Congress voted to suppress all forms of crown authority, to be replaced by locally created authority. Virginia, South Carolina, and New Jersey created their constitutions before July 4. Rhode Island and Connecticut simply took their existing royal charters and deleted all references to the crown.[105]

The new states had to decide not only what form of government to create, they first had to decide how to select those who would craft the constitutions and how the resulting document would be ratified. In states where the wealthy exerted firm control over the process, such as Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, New York and Massachusetts - the last-mentioned of these state's constitutions still being in force in the 21st century, continuously since its ratification on June 15, 1780 - the results were constitutions that featured:

- Substantial property qualifications for voting and even more substantial requirements for elected positions (though New York and Maryland lowered property qualifications);[104]

- Bicameral legislatures, with the upper house as a check on the lower;

- Strong governors, with veto power over the legislature and substantial appointment authority;

- Few or no restraints on individuals holding multiple positions in government;

- The continuation of state-established religion.

In states where the less affluent had organized sufficiently to have significant power—especially Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New Hampshire—the resulting constitutions embodied

- universal white manhood suffrage, or minimal property requirements for voting or holding office (New Jersey enfranchised some property owning widows, a step that it retracted 25 years later);

- strong, unicameral legislatures;

- relatively weak governors, without veto powers, and little appointing authority;

- prohibition against individuals holding multiple government posts;

Whether conservatives or radicals held sway in a state did not mean that the side with less power accepted the result quietly. The radical provisions of Pennsylvania's constitution lasted only 14 years. In 1790, conservatives gained power in the state legislature, called a new constitutional convention, and rewrote the constitution. The new constitution substantially reduced universal white-male suffrage, gave the governor veto power and patronage appointment authority, and added an upper house with substantial wealth qualifications to the unicameral legislature. Thomas Paine called it a constitution unworthy of America.[1]

Independence and Union

In April the North Carolina Provincial Congress issued the Halifax Resolves, explicitly authorizing its delegates to vote for independence.[106] In May Congress called on all the states to write constitutions, and eliminate the last remnants of royal rule.

By June nine colonies were ready for independence; one by one the last four —Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and New York — fell into line. Richard Henry Lee was instructed by the Virginia legislature to propose independence, and he did so on June 7, 1776. On the 11th a committee was created to draft a document explaining the justifications for separation from Britain. After securing enough votes for passage, independence was voted for on July 2. The Declaration of Independence, drafted largely by Thomas Jefferson and presented by the committee, was slightly revised and unanimously adopted by the entire Congress on July 4, marking the formation of a new sovereign nation, which called itself the United States of America.[107]

The Second Continental Congress approved a new constitution, the "Articles of Confederation," for ratification by the states on November 15, 1777, and immediately began operating under their terms. The Articles were formally ratified on March 1, 1781. At that point, the Continental Congress was dissolved and on the following day a new government of the United States in Congress Assembled took its place, with Samuel Huntington as presiding officer.[108][109]

Defending the Revolution

British return: 1776–1777

After Washington forced the British out of Boston in spring 1776, neither the British nor the Loyalists controlled any significant areas. The British, however, were massing forces at their naval base at Halifax, Nova Scotia. They returned in force in July 1776, landing in New York and defeating Washington's Continental Army at the Battle of Brooklyn in August, one of the largest engagements of the war. After the Battle of Brooklyn, the British requested a meeting with representatives from Congress to negotiate an end to hostilities.[110][111]

A delegation including John Adams and Benjamin Franklin met Howe on Staten Island in New York Harbor on September 11, in what became known as the Staten Island Peace Conference. Howe demanded a retraction of the Declaration of Independence, which was refused, and negotiations ended until 1781. The British then quickly seized New York City and nearly captured General Washington. They made the city their main political and military base of operations in North America, holding it until November 1783. New York City consequently became the destination for Loyalist refugees, and a focal point of Washington's intelligence network.[110][111]

The British also took New Jersey, pushing the Continental Army into Pennsylvania. In a surprise attack in late December 1776 Washington crossed the Delaware River back into New Jersey and defeated Hessian and British armies at Trenton and Princeton, thereby regaining New Jersey. The victories gave an important boost to pro-independence supporters at a time when morale was flagging, and have become iconic events of the war.

In 1777, as part of a grand strategy to end the war, the British sent an invasion force from Canada to seal off New England, which the British perceived as the primary source of agitators. In a major case of mis-coordination, the British army in New York City went to Philadelphia which it captured from Washington. The invasion army under Burgoyne waited in vain for reinforcements from New York, and became trapped in northern New York state. It surrendered after the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777. From early October 1777 until November 15 a pivotal siege at Fort Mifflin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania distracted British troops and allowed Washington time to preserve the Continental Army by safely leading his troops to harsh winter quarters at Valley Forge.

American alliances after 1778

The capture of a British army at Saratoga encouraged the French to formally enter the war in support of Congress, as Benjamin Franklin negotiated a permanent military alliance in early 1778, significantly becoming the first country to officially recognize the Declaration of Independence. On February 6, 1778, a Treaty of Amity and Commerce and a Treaty of Alliance were signed between the United States and France.[112] William Pitt spoke out in parliament urging Britain to make peace in America, and unite with America against France, while other British politicians who had previously sympathised with colonial grievances now turned against the American rebels for allying with British international rival and enemy.[113]

Later Spain (in 1779) and the Dutch (1780) became allies of the French, leaving the British Empire to fight a global war alone without major allies, and requiring it to slip through a combined blockade of the Atlantic. The American theater thus became only one front in Britain's war.[114] The British were forced to withdraw troops from continental America to reinforce the valuable sugar-producing Caribbean colonies, which were considered more important.

Because of the alliance with France and the deteriorating military situation, Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander, evacuated Philadelphia to reinforce New York City. General Washington attempted to intercept the retreating column, resulting in the Battle of Monmouth Court House, the last major battle fought in the north. After an inconclusive engagement, the British successfully retreated to New York City. The northern war subsequently became a stalemate, as the focus of attention shifted to the smaller southern theater.[115]

The British move South, 1778–1783

The British strategy in America now concentrated on a campaign in the southern colonies. With fewer regular troops at their disposal, the British commanders saw the "southern strategy" as a more viable plan, as the south was perceived as being more strongly Loyalist, with a large population of recent immigrants as well as large numbers of slaves who might be captured or run away to join the British.[116]

Beginning in late December 1778, the British captured Savannah and controlled the Georgia coastline. In 1780 they launched a fresh invasion and took Charleston as well. A significant victory at the Battle of Camden meant that royal forces soon controlled most of Georgia and South Carolina. The British set up a network of forts inland, hoping the Loyalists would rally to the flag.[117]

Not enough Loyalists turned out, however, and the British had to fight their way north into North Carolina and Virginia, with a severely weakened army. Behind them much of the territory they had already captured dissolved into a chaotic guerrilla war, fought predominantly between bands of Loyalist and American militia, which negated many of the gains the British had previously made.[117]

Yorktown 1781

The British army under Cornwallis marched to Yorktown, Virginia where they expected to be rescued by a British fleet.[118] The fleet showed up but so did a larger French fleet, so the British fleet after the Battle of the Chesapeake returned to New York for reinforcements, leaving Cornwallis trapped. In October 1781 under a combined siege by the French and Continental armies under Washington, the British surrendered their second invading army of the war.[119]

The end of the war

Support for the conflict had never been strong in Britain, where many sympathized with the rebels, but now it reached a new low.[120] Although King George III personally wanted to fight on, his supporters lost control of Parliament, and no further major land offensives were launched in the American Theater.[115][121]

Washington could not know that after Yorktown the British would not reopen hostilities. They still had 26,000 troops occupying New York City, Charleston and Savannah, together with a powerful fleet. The French army and navy departed, so the Americans were on their own in 1782–83.[122] The treasury was empty, and the unpaid soldiers were growing restive, almost to the point of mutiny or possible coup d'état. The unrest among officers of the Newburgh Conspiracy was personally dispelled by Washington in 1783, and Congress subsequently created the promise of a five years bonus for all officers.[123]

Peace treaty

The peace treaty with Britain, known as the Treaty of Paris, gave the U.S. all land east of the Mississippi River and south of the Great Lakes, though not including Florida (On September 3, 1783, Britain entered into a separate agreement with Spain under which Britain ceded Florida back to Spain.) The British abandoned the Indian allies living in this region; they were not a party to this treaty and did not recognize it until they were defeated militarily by the United States. Issues regarding boundaries and debts were not resolved until the Jay Treaty of 1795.[124] Since the blockade was lifted and the old imperial restrictions were gone, American merchants were free to trade with any nation anywhere in the world, and their businesses flourished.

Impact on Britain

Losing the war and the 13 colonies was a shock to Britain. The war revealed the limitations of Britain's fiscal-military state when it discovered it suddenly faced powerful enemies, with no allies, and dependent on extended and vulnerable transatlantic lines of communication. The defeat heightened dissension and escalated political antagonism to the King's ministers. Inside parliament, the primary concern changed from fears of an over-mighty monarch to the issues of representation, parliamentary reform, and government retrenchment. Reformers sought to destroy what they saw as widespread institutional corruption.[125][126]

The result was a powerful crisis, 1776–1783. The peace in 1783 left France financially prostrate, while the British economy boomed thanks to the return of American business. The crisis ended after 1784 thanks to the King's shrewdness in outwitting Charles James Fox (the leader of the Fox-North Coalition), and renewed confidence in the system engendered by the leadership of the new Prime Minister, William Pitt. Historians conclude that loss of the American colonies enabled Britain to deal with the French Revolution with more unity and better organization than would otherwise have been the case.[125][126]

Concluding the Revolution

Creating a "more perfect union" and guaranteeing rights

After the war finally ended in 1783, there was a period of prosperity, with the entire world at peace. The national government, still operating under the Articles of Confederation, was able to settle the issue of the western territories, which were ceded by the states to Congress. American settlers moved rapidly into those areas, with Vermont, Kentucky and Tennessee becoming states in the 1790s.[127]

However, the national government had no money to pay either the war debts owed to European nations and the private banks, or to pay Americans who had been given millions of dollars of promissory notes for supplies during the war. Nationalists, led by Washington, Alexander Hamilton and other veterans, feared that the new nation was too fragile to withstand an international war, or even internal revolts such as the Shays' Rebellion of 1786 in Massachusetts.

Calling themselves "Federalists," the nationalists convinced Congress to call the Philadelphia Convention in 1787.[128] It adopted a new Constitution that provided for a much stronger federal government, including an effective executive in a check-and-balance system with the judiciary and legislature.[129] After a fierce debate in the states over the nature of the proposed new government, the Constitution was ratified in 1788. The new government under President George Washington took office in New York in March 1789.[130] As assurances to those who were cautious about federal power, amendments to the Constitution guaranteeing many of the inalienable rights that formed a foundation for the revolution were spearheaded in Congress by James Madison, and later ratified by the states in 1791.

National debt

The national debt after the American Revolution fell into three categories. The first was the $12 million owed to foreigners—mostly money borrowed from France. There was general agreement to pay the foreign debts at full value. The national government owed $40 million and state governments owed $25 million to Americans who had sold food, horses, and supplies to the revolutionary forces. There were also other debts that consisted of promissory notes issued during the Revolutionary War to soldiers, merchants, and farmers who accepted these payments on the premise that the new Constitution would create a government that would pay these debts eventually.

The war expenses of the individual states added up to $114 million compared to $37 million by the central government.[131] In 1790, at the recommendation of first Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, Congress combined the remaining state debts with the foreign and domestic debts into one national debt totaling $80 million. Everyone received face value for wartime certificates, so that the national honor would be sustained and the national credit established.[132]

Effects of the Revolution

Loyalist expatriation

About 60,000 to 70,000 Loyalists left the newly founded republic; some left for Britain and the remainder, called United Empire Loyalists, received British subsidies to resettle in British colonies in North America, especially Quebec (concentrating in the Eastern Townships), Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia.[133] The new colonies of Upper Canada (now Ontario) and New Brunswick were created by Britain for their benefit. However, about 80% of the Loyalists stayed and became loyal citizens of the United States, and some of the exiles later returned to the U.S.[134]

Interpretations