Danny Kaye: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Fivetonsflax (talk | contribs) m →Cooking |

||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

In his later years he took to entertaining at home as chef – he had a special stove installed in his patio – and specialized in Chinese and Italian cooking.<ref name="Star"/> The specialized stove Kaye used for his Chinese dishes was fitted with special metal rings for the burners to allow the heat from them to be highly concentrated. Kaye needed to install a trough with circulating ice water so he could use the burners.<ref name=Today>{{cite web|url=http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/27054074|title=Marcella Hazan: Memoir of a classic Italian chef|date=7 October 2008|publisher=''Today''|accessdate=10 March 2011}}</ref> Kaye also taught Chinese cooking classes at a San Francisco Chinese restaurant in the 1970s.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=O2QtAAAAIBAJ&sjid=Y4kFAAAAIBAJ&pg=2509,4246744&hl=en|title=Danny Kaye Teaches Chinese Cooking|date=22 January 1974|publisher=Tri City Herald|accessdate=15 January 2011}}</ref> The theater and demonstration kitchen underneath the library at the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York is named for him.<ref>{{cite book|title=Cooking secrets of the CIA|editor=Culinary Institute of America|publisher=Chronicle Books|year=1995|pages=131|isbn=0-8118-1163-8|url=http://books.google.com/booksid=Au1XKfGD3kUC&pg=PA7&dq=danny+kaye+cooking#v=onepage&q&f=false|accessdate=18 January 2011}}</ref> |

In his later years he took to entertaining at home as chef – he had a special stove installed in his patio – and specialized in Chinese and Italian cooking.<ref name="Star"/> The specialized stove Kaye used for his Chinese dishes was fitted with special metal rings for the burners to allow the heat from them to be highly concentrated. Kaye needed to install a trough with circulating ice water so he could use the burners.<ref name=Today>{{cite web|url=http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/27054074|title=Marcella Hazan: Memoir of a classic Italian chef|date=7 October 2008|publisher=''Today''|accessdate=10 March 2011}}</ref> Kaye also taught Chinese cooking classes at a San Francisco Chinese restaurant in the 1970s.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=O2QtAAAAIBAJ&sjid=Y4kFAAAAIBAJ&pg=2509,4246744&hl=en|title=Danny Kaye Teaches Chinese Cooking|date=22 January 1974|publisher=Tri City Herald|accessdate=15 January 2011}}</ref> The theater and demonstration kitchen underneath the library at the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York is named for him.<ref>{{cite book|title=Cooking secrets of the CIA|editor=Culinary Institute of America|publisher=Chronicle Books|year=1995|pages=131|isbn=0-8118-1163-8|url=http://books.google.com/booksid=Au1XKfGD3kUC&pg=PA7&dq=danny+kaye+cooking#v=onepage&q&f=false|accessdate=18 January 2011}}</ref> |

||

Danny referred to his kitchen as "Ying's Thing". While filming ''The Madwoman of Chaillot'' in France, he phoned home to ask his family if they would like to eat at "Ying's Thing" that evening; Kaye then flew home for dinner.<ref name=Dena/> Not all of his efforts in the kitchen turned out well. After flying to San Francisco for a recipe for sourdough bread, he came home and spent hours preparing loaves. When his daughter asked about the bread, Kaye tried showing her by hitting the bread on the kitchen table. His bread was hard enough to chip it.<ref name=Dena/> Kaye approached his kitchen work with enthusiasm, making his own sausages and other items needed for his cuisine.<ref name=Today/><ref name=Writer/> His work as a chef earned him the "[[:fr:Meilleur ouvrier de France|Les Meilleurs Ouvriers de France]]" |

Danny referred to his kitchen as "Ying's Thing". While filming ''The Madwoman of Chaillot'' in France, he phoned home to ask his family if they would like to eat at "Ying's Thing" that evening; Kaye then flew home for dinner.<ref name=Dena/> Not all of his efforts in the kitchen turned out well. After flying to San Francisco for a recipe for sourdough bread, he came home and spent hours preparing loaves. When his daughter asked about the bread, Kaye tried showing her by hitting the bread on the kitchen table. His bread was hard enough to chip it.<ref name=Dena/> Kaye approached his kitchen work with enthusiasm, making his own sausages and other items needed for his cuisine.<ref name=Today/><ref name=Writer/> His work as a chef earned him the "[[:fr:Meilleur ouvrier de France|Les Meilleurs Ouvriers de France]]" culinary award; Kaye was the only non-professional to achieve this honor.<ref name=Conversation/> |

||

===Flying=== |

===Flying=== |

||

Revision as of 18:07, 15 May 2013

Danny Kaye | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | David Daniel Kaminsky January 18, 1913[1] Brooklyn, New York, USA |

| Died | March 3, 1987 (aged 74) |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, singer, comedian |

| Years active | 1933–1986 |

| Spouse | Sylvia Fine (m. 1940-1987; his death) 1 daughter |

| Children | Dena Kaye (b. 1946) |

Danny Kaye (born David Daniel Kaminsky; January 18, 1913 – March 3, 1987)[2] was a celebrated American actor, singer, dancer, and comedian. His best known performances featured physical comedy, idiosyncratic pantomimes, and rapid-fire nonsense songs.

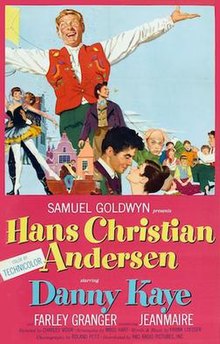

Kaye starred in 17 movies, notably The Kid from Brooklyn (1946), The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (1947), The Inspector General (1949), Hans Christian Andersen (1952), White Christmas (1954), and – perhaps his most accomplished performance – The Court Jester (1956). His films were extremely popular, especially his bravura performances of patter songs and children's favorites such as "Inchworm" and "The Ugly Duckling". He was the first ambassador-at-large of UNICEF in 1954 and received the French Legion of Honor in 1986 for his many years of work with the organization.[3]

Early years

David Daniel Kaminsky was born to Ukrainian Jewish immigrants in Brooklyn. Jacob and Clara Nemerovsky Kaminsky and their two sons, Larry and Mac, left Ekaterinoslav two years before his birth; he was the only one of their sons born in the United States.[4] He spent his early youth attending Public School 149 in East New York, Brooklyn—which eventually would be renamed to honor him[5]—where he began entertaining his classmates with songs and jokes,[6] before moving to Thomas Jefferson High School, but he never graduated.[7] His mother died when he was in his early teens. Clara had enjoyed the impressions and humor of her youngest son and always had words of encouragement for them; her death was a great loss for the young Kaye.

Not long after his mother's death, Kaye and his best friend ran away to Florida. Kaye sang while his friend Louis played the guitar; the pair eked out a living like this for a while. When Kaye returned to New York, his father did not pressure him to return to school or get a job, giving his son the chance to mature and discover his own abilities.[8] Kaye said he had wanted to become a surgeon as a young boy, but there was no chance of the family being able to afford a medical school education for him.[4][9] He held a succession of jobs after leaving school: soda jerk, insurance investigator, office clerk. Most of them ended with his being fired. He lost the insurance job when he made an error that cost the insurance company $40,000. The dentist who had hired him to look after his office during his lunch hour did the same when he found Kaye using his drill to create designs in the office woodwork.[4][10] He learned his trade in his teenage years in the Catskills as a tummler in the Borscht Belt,[6] especially for four seasons at The White Roe resort.[11]

Kaye's first break came in 1933 when he was asked to become one of the "Three Terpsichoreans", a vaudeville dance act. He opened with them in Utica, New York using the name Danny Kaye for the first time.[6] The act toured the United States, then signed on to perform in the Orient with the show La Vie Paree.[12] The troupe left for six months in the Far East on February 8, 1934. While the group was in Osaka, Japan, a typhoon hit the city. The hotel Kaye and his colleagues stayed in suffered heavy damage; a piece of the hotel's cornice was hurled into Kaye's room by the strong wind, nearly killing him. By performance time that evening, the city was still in the grip of the storm. There was no power and the audience had become understandably restless and nervous. To keep everyone calm, Kaye went on stage, his face lit by a flashlight, and sang every song he could recall as loudly as he was able.[4] The experience of trying to entertain audiences who did not speak English is what brought him to the pantomimes, gestures, songs and facial expressions which eventually made him famous.[6][10] Sometimes it was necessary just to try to get a meal. Kaye's daughter, Dena, tells a story her father related about being at a restaurant in China and trying to order chicken. Kaye flapped his arms and clucked, giving the waiter his best imitation of a chicken. The waiter nodded his understanding, bringing Kaye two eggs. His interest in cooking began on the tour.[6][12]

When he returned to the United States, jobs were in short supply; Kaye struggled for bookings. One of the jobs was working in a burlesque revue with fan dancer Sally Rand. After the dancer dropped one of her fans while trying to chase away a fly, Kaye was hired to be in charge of the fans so they were always held in front of her.[6][10]

Career

Danny Kaye made his film debut in a 1935 comedy short Moon Over Manhattan. In 1937 he signed with New York–based Educational Pictures for a series of two-reel comedies. Kaye usually played a manic, dark-haired, fast-talking Russian in these low-budget shorts, opposite young hopefuls June Allyson or Imogene Coca. The Kaye series ended abruptly when the studio shut down permanently in 1938. He was still working in the Catskills at times in 1937, using the name Danny Kolbin.[13][14] Kaye's next venture was a short-lived Broadway show, where Sylvia Fine was the pianist, lyricist and composer. The Straw Hat Revue opened on September 29, 1939, and closed after ten weeks, but it was long enough for critics to take notice of Kaye's work in it.[4][15] The glowing reviews brought an offer for both Kaye and his new bride, Sylvia, to work at La Martinique, an upscale New York City nightclub. Kaye performed with Sylvia as his accompanist. At La Martinique, playwright Moss Hart saw Danny perform, which led to Hart casting him in his hit Broadway comedy Lady in the Dark.[4][10]

Kaye scored a personal triumph in 1941 in Lady in the Dark. His show-stopping number was "Tchaikovsky", by Kurt Weill and Ira Gershwin, in which he sang the names of a whole string of Russian composers at breakneck speed, seemingly without taking a breath.[16][17] By the next Broadway season, he was the star of his own show about a young man who is drafted called Let's Face It!.[18]

His feature film debut was in producer Samuel Goldwyn's Technicolor 1944 comedy Up in Arms,[19] a remake of Goldwyn's Eddie Cantor comedy Whoopee! (1930).[20] Kaye's rubber face and fast patter were an instant hit,[citation needed] and rival producer Robert M. Savini cashed in almost immediately by compiling three of Kaye's old Educational Pictures shorts into a makeshift feature, The Birth of a Star (1945).[21] Studio mogul Goldwyn wanted Kaye to have his prominent nose fixed so it would look less Jewish,[11][22] but Kaye refused. However, he did allow his natural red hair to be dyed blonde, apparently because it looked better that way in Technicolor.[22]

Kaye starred in a radio program of his own, The Danny Kaye Show, on CBS in 1945–1946.[23] Its cast included Eve Arden, Lionel Stander, and Big Band leader Harry James, and it was scripted by radio notable Goodman Ace and respected playwright-director Abe Burrows.

The radio program's popularity rose quickly. Before Kaye had been on the air a year, he tied with Jimmy Durante for fifth place in the Radio Daily popularity poll.[10] Kaye was asked to participate in a USO tour following the end of World War II. It meant he would be absent from his radio show for close to two months at the beginning of the season. Kaye's friends filled in for him, with a different guest host each week.[24] Kaye was the first American actor to visit postwar Tokyo; it was his first time there after touring there some ten years before with the vaudeville troupe.[25][26] When Kaye asked to be released from his radio contract in mid-1946, he agreed not to accept another regular radio show for one year and also to limit his guest appearances on the radio programs of others.[24][27] Many of the show's episodes survive today, and are notable for Kaye's opening "signature" patter.[10]

"Git gat gittle, giddle-di-ap, giddle-de-tommy, riddle de biddle de roop, da-reep, fa-san, skeedle de woo-da, fiddle de wada, reep!"

Kaye was sufficiently popular that he inspired imitations:

- The 1946 Warner Bros. cartoon Book Revue had a lengthy sequence with Daffy Duck impersonating Kaye singing "Carolina in the Morning" with the Russian accent that Kaye would affect from time to time.

- Satirical songwriter Tom Lehrer's 1953 song "Lobachevsky" was based on a number that Kaye had done, about the Russian director Constantin Stanislavski, again with the affected Russian accent. Lehrer mentioned Kaye in the opening monologue, citing him as an "idol since childbirth".

- Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster also fashioned a short-lived superhero title, Funnyman, taking inspiration from Kaye's persona.

Kaye starred in several movies with actress Virginia Mayo in the 1940s, and is well known for his roles in films such as The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (1947), The Inspector General (1949), On the Riviera (1951) co-starring Gene Tierney, Knock on Wood (1954), White Christmas (1954, in a role originally intended for Fred Astaire, then Donald O'Connor),The Court Jester (1956), and Merry Andrew (1958). Kaye starred in two pictures based on biographies, Hans Christian Andersen (1952) about the Danish story-teller, and The Five Pennies (1959) about jazz pioneer Red Nichols. His wife, writer/lyricist Sylvia Fine, wrote many of the witty, tongue-twisting songs Danny Kaye became famous for.[9][28] She was also an associate producer.[29] Some of Kaye's films included the theme of doubles, two people who look identical (both played by Danny Kaye) being mistaken for each other, to comic effect.

Kaye teamed with the very popular Andrews Sisters (Patty, Maxene, and LaVerne) on Decca Records in 1947, producing the number-three Billboard smash hit "Civilization (Bongo, Bongo, Bongo)". The success of the pairing prompted both acts to record repeatedly through 1950, producing such rhythmically comical fare as "The Woody Woodpecker Song" (based on the frisky bird from the Walter Lantz cartoons, and another Billboard hit for the quartet), "Put 'em in a Box, Tie 'em with a Ribbon (And Throw 'em in the Deep Blue Sea)," "The Big Brass Band from Brazil," "It's a Quiet Town (In Crossbone County)," "Amelia Cordelia McHugh (Mc Who?)," "Ching-a-ra-sa-sa", and a duet by Danny and Patty of "Orange Colored Sky". The acts also teamed for two yuletide favorites: a frantic, melodious, harmonic rendition of "A Merry Christmas at Grandmother's House (Over the River and Through the Woods)", and another duet by Danny & Patty, "All I Want for Christmas Is My Two Front Teeth"[30]

While his wife wrote Kaye's material, there was much of it that was unwritten, springing from the mind of Danny Kaye, often while he was performing. Kaye had one character he never shared with the public; Kaplan, the owner of an Akron, Ohio rubber company, came to life only for family and friends. His wife Sylvia described the Kaplan character:[31]

He doesn't have any first name. Even his wife calls him just Kaplan. He's an illiterate pompous character who advertises his philanthropies. Jack Benny or Dore Schary might say, "Kaplan, why do you hate unions so?" If Danny feels like doing Kaplan that night, he might be off on Kaplan for two hours.

When he appeared at the London Palladium music hall in 1948, he "roused the Royal family to shrieks of laughter and was the first of many performers who have turned English variety into an American preserve." Life magazine described his reception as "worshipful hysteria" and noted that the royal family, for the first time in history, left the royal box to see the show from the front row of the orchestra.[32][33][34] He later related that he had no idea of the familial connections when the Marquess of Milford Haven introduced himself after one of the shows and said he would like his cousins to see Kaye perform.[17] Kaye also later stated that he never returned to the venue because there was no way to re-create the magic of that time.[35] Kaye had an invitation to return to London for a Royal Variety Performance in November of the same year.[36] When the invitation arrived, Kaye was busy at work on The Inspector General (which had a working title of Happy Times for a while). Warners stopped work on the film to allow their star to attend.[37] When his Decca co-workers The Andrews Sisters began their engagement at the London Palladium directly on the heels of Kaye's incredibly successful 1948 appearance there, the trio was so well received that David Lewin of the Daily Express declared, "The audience gave The Andrews Sisters the Danny Kaye roar!"[30]

He hosted the 24th Academy Awards in 1952. The program was broadcast only on radio. Telecasts of the Oscar ceremony would come later. During the 1950s, Kaye visited Australia, where he played "Buttons" in a production of Cinderella in Sydney. In 1953, Kaye started his own production company, Dena Pictures, named for his daughter. Knock on Wood was the first film produced by his firm. The firm expanded into television in 1960 under the name Belmont Television.[38][39]

Kaye entered the world of television in 1956 through the CBS show See It Now with Edward R. Murrow.[40] The Secret Life of Danny Kaye combined his 50,000-mile, ten-country tour as UNICEF ambassador with music and humor.[41][42] His first solo effort was in 1960 with an hour-long special produced by Sylvia and sponsored by General Motors; there were similar specials in 1961 and 1962.[4] He hosted his own variety hour on CBS television, The Danny Kaye Show, from 1963 to 1967, which won four Emmy awards and a Peabody award.[43][44] During this period, beginning in 1964, he acted as television host to the annual CBS telecasts of MGM's The Wizard of Oz. Kaye also did a stint as one of the What's My Line? Mystery Guests on the popular Sunday night CBS-TV quiz program. Kaye later served as a guest panelist on that show. He also appeared on the NBC interview program Here's Hollywood.

In the 1970s Kaye tore a ligament in his leg during the run of the Richard Rodgers musical Two by Two, but went on with the show, appearing with his leg in a cast and cavorting on stage from a wheelchair.[43][45] He had done much the same on his television show in 1964 when his right leg and foot were seriously burned from an at-home cooking accident. The camera shots were planned so television viewers did not see Kaye in his wheelchair.[46]

In 1976, he played the role of Mister Geppetto in a television musical adaptation of Pinocchio with Sandy Duncan in the title role. Kaye also portrayed Captain Hook opposite Mia Farrow in a musical version of Peter Pan featuring songs written by Anthony Newley and Leslie Bricusse. It was shown on NBC-TV in December 1976 as part of the Hallmark Hall of Fame series. He guest-starred much later in his career in episodes of The Muppet Show, The Cosby Show[47] and in the 1980s revival of The Twilight Zone.

In many of his movies, as well as on stage, Kaye proved to be a very able actor, singer, dancer and comedian. He showed quite a different and serious side as Ambassador for UNICEF and in his dramatic role in the memorable TV movie Skokie, in which he played a Holocaust survivor.[43] Before his death in 1987, Kaye demonstrated his ability to conduct an orchestra during a comical, but technically sound, series of concerts organized for UNICEF fundraising. Kaye received two Academy Awards: an Academy Honorary Award in 1955 and the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award in 1982.[16] Also that year he received the Screen Actors Guild Annual Award.[16]

Kaye was enamored of music. While he often claimed an inability to read music, he was quite the conductor and was said to have perfect pitch. Kaye's ability with an orchestra was brought up by Dimitri Mitropoulos, who was then the conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. After Kaye's guest appearance, Mitropoulos remarked, "Here is a man who is not musically trained, who cannot even read music, and he gets more out of my orchestra than I ever have."[7] Kaye was often invited to conduct symphonies as charity fundraisers[9][16] and was the conductor of the all-city marching band at the season opener of the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1984. Over the course of his career he raised over US$5,000,000 in support of musicians pension funds.[48]

In 1980, Kaye hosted and sang in the 25th Anniversary of Disneyland celebration, and hosted the opening celebration for Epcot in 1982 (EPCOT Center at the time), both of which were aired on prime-time American television.

Other projects

Cooking

In his later years he took to entertaining at home as chef – he had a special stove installed in his patio – and specialized in Chinese and Italian cooking.[16] The specialized stove Kaye used for his Chinese dishes was fitted with special metal rings for the burners to allow the heat from them to be highly concentrated. Kaye needed to install a trough with circulating ice water so he could use the burners.[49] Kaye also taught Chinese cooking classes at a San Francisco Chinese restaurant in the 1970s.[50] The theater and demonstration kitchen underneath the library at the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York is named for him.[51]

Danny referred to his kitchen as "Ying's Thing". While filming The Madwoman of Chaillot in France, he phoned home to ask his family if they would like to eat at "Ying's Thing" that evening; Kaye then flew home for dinner.[12] Not all of his efforts in the kitchen turned out well. After flying to San Francisco for a recipe for sourdough bread, he came home and spent hours preparing loaves. When his daughter asked about the bread, Kaye tried showing her by hitting the bread on the kitchen table. His bread was hard enough to chip it.[12] Kaye approached his kitchen work with enthusiasm, making his own sausages and other items needed for his cuisine.[49][52] His work as a chef earned him the "Les Meilleurs Ouvriers de France" culinary award; Kaye was the only non-professional to achieve this honor.[7]

Flying

Like many in the film business, Danny was an aviation enthusiast. He became seriously interested in learning how to fly in 1959. An enthusiastic and accomplished golfer, Kaye gave up golf in favor of flying.[53] When Kaye went for his first written pilot's exam, he brought a liverwurst sandwich in case he was there for hours. The first plane Kaye owned was a Piper Aztec.[54][55] Kaye got his first license as a private pilot of multi-engine aircraft, not getting certified for operating a single engine plane until six years later.[54] He was an accomplished pilot, rated for airplanes ranging from single-engine light aircraft to multi-engine jets.[16] Kaye held a commercial pilot's license and had flown every type of aircraft except military planes.[7][54][56] A vice-president of Learjet, Kaye owned and operated a Learjet 24.[54] He supported many flying projects. In 1968, he was Honorary Chairman of the Las Vegas International Exposition of Flight, a major show that utilized most facets of the city’s entertainment industry while presenting a major air show. The operational show chairman was well-known aviation figure Lynn Garrison. Kaye flew his own plane to 65 cities in five days on a mission designed to help UNICEF.[7]

Danny Kaye was very fond of the legendary arranger Vic Schoen. Schoen had arranged for him on White Christmas, The Court Jester, and albums and concerts with the Andrews Sisters. In the 1960s Vic Schoen was working on a show in Las Vegas with Shirley Temple. He was injured in a car accident. When Danny Kaye heard about the accident, he immediately flew his own plane to McCarran Airport to pick up Schoen and bring him back to Los Angeles to guarantee the best medical attention.

Baseball

Kaye was part-owner of baseball's Seattle Mariners along with his partner Lester Smith from 1977 to 1981.[16][57] Prior to that, the lifelong fan of the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers recorded a song called "The D-O-D-G-E-R-S Song (Oh really? No, O'Malley!)", describing a fictitious encounter with the San Francisco Giants, which was a hit during the real-life pennant chase of 1962. That song is included on Baseball's Greatest Hits compact discs. A good friend of Leo Durocher, he would often travel with the team.[10] In addition to being an owner, Kaye had an encyclopedic knowledge of the game.[16]

Medicine

He was an honorary member of the American College of Surgeons and the American Academy of Pediatrics.[16]

Charity

Throughout his life, Kaye donated to various charities. Working alongside UNICEF's Halloween fundraiser founder, Ward Simon Kimball Jr., the actor educated the public on impoverished children in deplorable living conditions overseas and assisted in the distribution of donated goods and funds. His involvement with UNICEF came about in a very unusual way. Kaye was flying home from an appearance in London in 1949 when one of the plane's four engines lost its propeller and caught fire. The problem was initially thought to be serious enough that it might need to make an ocean landing; life jackets and life rafts were made ready. The plane was able to head back over 500 miles to make a landing in Shannon, Ireland. On the way back to Shannon, the head of the Children's Fund, Maurice Pate, had the seat next to Danny Kaye and spoke at length to him about the need for recognition for the Fund. Their discussion continued on the flight from Shannon to New York; it was the beginning of the actor's long association with UNICEF.[58][59]

Death

Kaye died of a heart attack in March 1987, following a bout of hepatitis. Kaye had quadruple bypass heart surgery in February 1983; he contracted hepatitis from a blood transfusion he received at that time.[16][47] He left a widow, Sylvia Fine, and a daughter, Dena.[60] He is interred in Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York. His grave is adorned with a bench that contains friezes of a baseball and bat, an aircraft, a piano, a flower pot, musical notes, and a glove. Kaye's name, birth and death dates are inscribed on the glove.[61] The United Nations held a memorial tribute to him at their New York headquarters.[62][63]

Personal life

Kaye and his wife, Sylvia, both grew up in Brooklyn, living only a few blocks apart, but they did not meet until they were both working on an off-Broadway show in 1939.[64] Sylvia was an audition pianist at the time.[9][28][65] Sylvia discovered that Danny had once worked for her father, dentist Samuel Fine.[10] They were married on January 3, 1940.[60][66] Kaye, working in Florida at the time, proposed on the telephone; the couple was married in Fort Lauderdale.[67] Their daughter, Dena, was born on December 17, 1946.[15][68]

Both Kaye and his wife raised their daughter without any parental hopes or aspirations for her future. Kaye said in a 1954 interview, "Whatever she wants to be she will be without interference from her mother nor from me."[8][52] When she was very young, Dena did not like seeing her father perform because she did not understand that people were supposed to laugh at what he did.[69] On January 18, 2013, during a 24-hour salute to Kaye on Turner Classic Movies in celebration of his 100th birthday, Kaye's daughter Dena revealed to TCM host Ben Mankiewicz that Kaye was actually born in 1911.

During World War II, the Federal Bureau of Investigation investigated rumors that Kaye dodged the draft by manufacturing a medical condition to gain 4-F status and exemption from military service. FBI files show he was also under investigation for supposed links with Communist groups. The allegations were never substantiated, and he was never charged with any associated crime.[70]

After Kaye and his wife became estranged,ca. 1947[15][71][72] he was allegedly involved with a succession of women, though he and Fine never divorced.[73][74] The best-known of these women was actress Eve Arden.[75][76]

There are persistent claims that Kaye was homosexual or bisexual, and some sources assert that Kaye and Laurence Olivier had a ten-year relationship in the 1950s while Olivier was still married to Vivien Leigh.[77] A biography of Leigh states that their love affair caused her to have a breakdown.[78] The affair has been denied by Olivier's official biographer, Terry Coleman.[79] Joan Plowright, Olivier's third wife and widow, has dealt with the matter in different ways on different occasions: she deflected the question (but alluded to Olivier's "demons") in a BBC interview.[80] She is reputed to have referred to Danny Kaye on another occasion, in response to a claim that it was she who broke up Olivier's marriage to Leigh. However, in her own memoirs, Plowright denies that there had been an affair between the two men.[81] Producer Perry Lafferty reported: "People would ask me, 'Is he gay? Is he gay?' I never saw anything to substantiate that in all the time I was with him.”[75] Kaye’s final girlfriend, Marlene Sorosky, reported that he told her, "I've never had a homosexual experience in my life. I've never had any kind of gay relationship. I've had opportunities, but I never did anything about them."[75]

Honors, awards, tributes

- Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award (1981)

- Asteroid 6546 Kaye

- Danny Kaye has three stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for his work in music, radio, and films.[82]

- Danny Kaye was knighted by Queen Margrethe II of Denmark in 1983 for his 1952 portrayal of Hans Christian Andersen in the film of the same name.[60]

- Kennedy Center Honor (1984)

- Grand Marshal of the Tournament of Roses Parade (1984)

- French Legion of Honor (Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur) on 24 February 1986 for his UNICEF work.[3]

- The song "I Wish I Was Danny Kaye" on Miracle Legion's 1996 album Portrait of a Damaged Family

- On June 23, 1987, Kaye was posthumously presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Ronald Reagan. The award was received by his daughter Dena.[83][84]

- UNICEF's New York Visitor's Centre is named to honor Danny Kaye.[85]

- In December 1996, the PBS series, American Masters, aired a special on the life of Danny Kaye.[35]

Filmography

Film

Television

- Autumn Laughter (1938) (experimental telecast)

- The Secret Life of Danny Kaye (1956) (See It Now special)

- An Hour With Danny Kaye (1960 and 1961) (specials)

- The Danny Kaye Show with Lucille Ball (1962) (special)

- The Danny Kaye Show (1963–1967) (series)

- The Lucy Show: "Lucy Meets Danny Kaye" (1964) (guest appearance)

- Here Comes Peter Cottontail (1971) (voice)

- The Dick Cavett Show (1971) (interview guest)

- The Enchanted World of Danny Kaye: The Emperor's New Clothes (1972) (special)

- An Evening with John Denver (1975) (special)

- Pinocchio (1976 TV-musical) (1976) (special), live television musical adaptation starring Sandy Duncan and Danny Kaye

- Peter Pan (1976) (special)

- The Muppet Show (1978) (guest appearance)

- Disneyland's 25th Anniversary (1980) (special guest appearance)

- An Evening with Danny Kaye (1981) (special)

- Skokie (1981)

- The New Twilight Zone: "Paladin of the Lost Hour" (1985) (guest appearance)

- The Cosby Show: "The Dentist" (1986) (guest appearance)

Stage Work

- The Straw Hat Revue (1939)

- Lady in the Dark (1941)

- Let's Face It! (1941)

- Two by Two (1970)

Discography

Studio Albums

- The Five Pennies with Louis Armstrong (1959)

- Mommy, Gimme a Drinka Water (Orchestration by Gordon Jenkins) (Capitol Records, 1959)

Soundtracks

- Hans Christian Andersen (1952)

Story Albums

Compilations

References

- ^ Dena Kaye interview on TCM January 18, 2013. Her father was actually born in 1911 but, for reasons unknown to her, changed it to 1913

- ^ Tony Woolway (4 March 1987). "Danny Kaye Dies, Age 74". icWales. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- ^ a b "French Honor Danny Kaye". The Modesto Bee. 26 February 1986. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Adir, Karen, ed. (2001). The Great Clowns of American Television. McFarland & Company. p. 270. ISBN 0-7864-1303-4. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ "Welcome P.S. 149 Danny Kaye". NY City Dept of Education. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "World-renown comedian dies". Eugene Register-Guard. 4 March 1987. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Goodman, Mark (23 December 1979). "A Conversation With Danny Kaye". Lakeland Ledger. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ a b Perry, Lawrence (9 May 1954). "Danny Kaye Looks At Life". The Milwaukee Journal. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d Battelle, Phyllis (8 May 1959). "Mrs. Danny Kaye Proves a Genius". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Git Gat Gittle". Time. 11 March 1946. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ a b Kanfer, Stefan (1989). A summer world : the attempt to build a Jewish Eden in the Catskills from the days of the ghetto to the rise and decline of the Borscht Belt (1st ed. ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. p. 157. ISBN 978-0374271800.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d Kaye, Dena (19 January 1969). "Life With My Zany Father-Danny Kaye". Tri City Herald. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ ""Highlights and Shadows"-front of program". The President Players. 4 July 1937. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ ""Highlights and Shadows"-inside of program". The President Players. 4 July 1937. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ a b c "Who Is Sylvia?". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 30 October 1960. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Danny Kaye, comedian who loved children, dead at 74". Star-News. 4 March 1987. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ a b Remington, Fred (12 January 1964). "Danny Kaye: King of Comedy". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Edel, Leon (8 November 1941). "Danny Kaye as Musical Draftee Brightens the Broadway Scene". Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ Up In Arms at the Internet Movie Database

- ^ Whittaker, Herbert (20 May 1944). "Danny Kaye Makes Successful Debut in 'Up In Arms'". The Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ "The Birth of a Star". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ a b Nolan, J. Leigh. "Danny! Danny Kate F.A.Q.s". J. Leigh Nolan. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ Foley, Roy L. (2 February 1946). "Helen and Danny: O-Kaye! Crowd Howls". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ a b "Danny Kaye". DigitalDeli. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ a b BCL (12 November 1945). "Riding the Airwaves". The Milwaukee Journal. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ "Lily Pons the Guest Star Tonight Of Danny Kaye, Back From Tour". The Montreal Gazette. 23 November 1945. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ "Hollywood". The Milwaukee Sentinel. 2 May 1946. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

{{cite news}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ a b Boyle, Hal (27 August 1959). "Composer Sylvia Fine Can Write Anywhere Anytime". The Sunday News-Press. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ Brady, Thomas F. (13 November 1947). "Danny Kaye Film Set at Warners". The Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ a b Sforza, John: Swing It! The Andrews Sisters Story. University Press of Kentucky, 2000; 289 pages.

- ^ Wilson, Earl (4 July 1959). "It Happened Last Night". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ Young, Andrew (4 March 1987). "Kaye: everyone's favourite". The Glasgow Herald. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Januzzi, Gene (23 October 1949). "Danny Kaye Won't Talk of Royalty". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Handsaker, Gene (11 October 1948). "Danny Kaye Is a Real Showoff". Kentucky New Era. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ a b Bianculli, David (10 December 1996). "The Many Lives of Danny Kaye". New York Daily News. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ "Royal Variety Performance". Entertainment Artistes Benenevolent Fund. 1948. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ "Royal Invitation for Danny Kaye". The Montreal Gazette. 20 October 1948. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ Goldie, Tom (10 July 1953). "Friday Film Notes-Danny--Producer". Evening Times. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ "Danny Kaye Founds Film Firm". The Pittsburgh Press. 6 December 1960. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ McManus, Margaret (23 September 1956). "Found at Last: A Happy Comedian". The Milwaukee Journal. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Mercer, Charles (5 December 1956). "Danny Kaye Gives TV Its Finest 90 Minutes". The Miami News. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ Pearson, Howard (3 December 1956). "Color Shows, Danny Kaye, Draw Attention". The Deseret News. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ a b c Drew, Mike (4 March 1987). "Danny Kaye always excelled as an entertainer and in life". The Milwaukee Journal. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ "The Danny Kaye Episode Guide". Mateas Media Consulting. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ Raidy, William A. (17 February 1971). "Real people go to matinees and Danny Kaye loves 'em". The Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ Lowry, Cynthia (17 April 1964). "Accident Confines Danny Kaye to Chair". Eugene Register-Guard. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ a b "Actor-comedian Danny Kaye dies". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 3 March 1987. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ "Biography of Danny Kaye". The Kennedy Center. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- ^ a b "Marcella Hazan: Memoir of a classic Italian chef". Today. 7 October 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Danny Kaye Teaches Chinese Cooking". Tri City Herald. 22 January 1974. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Culinary Institute of America, ed. (1995). Cooking secrets of the CIA. Chronicle Books. p. 131. ISBN 0-8118-1163-8. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ a b Boyd, Joseph G. (23 May 1980). "Travel writer attends party saluting hotel". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Scott, Vernon (14 July 1962). "Kaye Likes Air". The Windsor Star. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d Kaye, Danny (January 1967). If I Can Fly, You Can Fly. Popular Science. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (21 September 1965). "Danny Kaye Likes Flying, TV, Dodgers". Gettysburg Times. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Smith, Red (12 June 1976). "American League's a new act for Danny Kaye". The Miami News. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ "Major League Baseball Returns To Seattle". The Leader-Post. 9 February 1976. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ "Crippled Transport Limps to Safety". The Lewiston Daily Sun. 8 July 1949. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ "Danny Kaye". UNICEF. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ a b c "Movie producer, songwriter Sylvia Fine Kaye dies at 78". Daily News. 29 October 1991. Retrieved 27 November 2010. Cite error: The named reference "Obit" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Photo of Bench-Danny Kaye". Find a Grave. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ Taylor, Clarke (23 October 1987). "UN and Friends Pay Tribute to Kaye". LA Times. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ Lewis, Paul (22 October 1987). "U.N. Praises Danny Kaye at Tribute". New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 March 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ "A team grew in Brooklyn". The Dispatch. 25 April 1975. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ "Kaye at the Met". The Evening News. 25 April 1975. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ Wilson, Earl (4 July 1959). "Danny Kaye To End TV Holdout; Wife To Write Script". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Raymer, Dorothy (6 November 1945). "Who Is Sylvia? What Is She?-Danny Kaye's Inspiration". The Miami News. Retrieved 14 January 1945.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Parsons, Louella (28 July 1946). "Danny Kaye Awaits Christmas Bulletin On Maternity Front". The News and Courier. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ Hughes, Alice (28 January 1953). "A Woman's New York". Reading Eagle. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Freedom of Information/Privacy Act Section. "Subject: Danny Kaye". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Cheney, Carlton (26 October 1947). "The Secret Life of Danny Kaye". The Milwaukee Journal. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Handsaker, Gene (11 December 1947). "Like Peas In Pod Are Film Married Duos". The Deseret News. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (13 January 1948). "Opportunities Galore In Films For Women". Waycross Journal-Herald. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ MacPherson, Virginia (9 February 1948). "Hollywood Report". Oxnard Press-Courier. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ a b c Gottfried, Martin (1994). Nobody's Fool: The Lives of Danny Kaye. New York; London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-86494-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Parsons, Louella (21 February 1948). "Movie Comedy Is Easy for Eve Arden". The Deseret News. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ Spoto, Donald (1992). Laurence Olivier: A Biography. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-018315-2.

- ^ Capua, Michelangelo (2003). Vivien Leigh: A Biography. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1497-9.

- ^ Coleman, Terry (2006). "Author's Note: The Androgynous Actor". Olivier. Macmillan. pp. 478–481. ISBN 0-8050-8136-4.

- ^ "Olivier Had 'Demons', Says Widow Answering Gay Question". Contactmusic.com. 26 August 2006. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ Christiansen, Rupert (13 October 2001). "Tending the sacred flame". The Spectator. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "Danny Kaye-Hollywood Star Walk". LA Times. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ "Kaye, Willson to Get Medal of Freedom". LA Times. 22 April 1987. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ "Remarks at the Presentation Ceremony for the Presidential Medal of Freedom". University of Texas. 23 June 1987. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ "Danny Kaye Visitor's Centre Virtual Tour". UNICEF. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ "Moon Over Manhattan". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ "Dime a Dance". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ "Getting an Eyeful". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ "Cupid Takes a Holiday". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ "Money on Your Life". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ The 16 minute film, I Am an American, was featured in American theaters as a short feature in connection with "I Am an American Day" (now called Constitution Day). I Am an American was produced by Gordon Hollingshead, also written by Crane Wilbur. See: I Am An American at the TCM Movie Database and I Am an American at IMDb.

Sources

External links

- Danny Kaye at IMDb

- Danny Kaye tribute and fan website

- Tribute to Danny Kaye in The Court Jester

- Danny! – The Definitive Danny Kaye Fan Site

- Royal Engineers Museum Danny Kaye in Korea 1952

- Literature on Danny Kaye

- N.Y. Times Obituary for Danny Kaye

Listen

- The Danny Kaye Show on radio at Internet Archive.

- The Danny Kaye Show more radio episodes at Internet Archive.

Watch

- The Inspector General for iPod at Internet Archive.

- The Inspector General at Internet Archive.

- Use dmy dates from October 2012

- 1913 births

- 1987 deaths

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- American aviators

- American male comedians

- American film actors

- American stage actors

- American television actors

- Major League Baseball owners

- Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- Deaths from hepatitis

- Emmy Award winners

- Jewish comedians

- Kennedy Center honorees

- People from Brooklyn

- Aviators from New York

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Seattle Mariners owners

- American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent

- Vaudeville performers

- Peabody Award winners

- Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur

- UNICEF people

- Jewish American actors

- 20th-century American actors

- Burials at Kensico Cemetery

- American male actors

- American male dancers

- Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award winners