Monte Carlo integration: Difference between revisions

made function name consistent |

|||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

A paradigmatic example of a Monte Carlo integration is the estimation of π. Consider the function |

A paradigmatic example of a Monte Carlo integration is the estimation of π. Consider the function |

||

:<math>H |

:<math>H\left(x,y\right)=\begin{cases} |

||

1 & \text{if }x^{2}+y^{2}\leq1\\ |

1 & \text{if }x^{2}+y^{2}\leq1\\ |

||

0 & \text{else} |

0 & \text{else} |

||

Revision as of 02:57, 1 June 2013

In mathematics, Monte Carlo integration is a technique for numerical integration using random numbers. It is a particular method of Monte Carlo methods that numerically computes a definite integral. While other algorithms usually evaluate the integrand at a regular grid,[1] Monte Carlo algorithms randomly choose the points at which the integrand is evaluated.[2] This method is particularly useful for higher dimensional integrals.[3]

Informally, to estimate the area of a domain D, first pick a simple domain E whose area is easily calculated and which contains D. Now pick a sequence of random points that fall within E. Some fraction of these points will also fall within D. The area of D is then estimated as this fraction multiplied by the area of E.

Particular techniques to perform a Monte Carlo integration can be considered. Uniform sampling, stratified sampling and importance sampling are the most common.

Overview

Consider the set Ω, subset of Rm on which the multidimensional definite integral

is to be calculated with known volume of Ω

The most naive approach to compute I is to sample points uniformly on Ω:[4] given N uniform samples,

I can be approximated by

- .

This is because the law of large numbers ensures that

- .

One has to take into account that implementation issues such as pseudorandom number generators and limited floating point precision can lead to systematic errors, nevertheless, only in very particular cases this has to be taken into account.

Given the estimation of I from QN, the error bars of QN can be estimated by the sample variance using the unbiased estimate of the variance:

which leads to

- .

As long as the sequence

is bounded, this variance decreases asymptotically to zero as 1/N. The estimation of the error of QN is thus

which decreases as and the familiar law of random walk applies: to reduce the error by a factor of 10 requires a 100-fold increase in the number of sample points. This result is quite strong in the sense that it does not depend on the number of dimensions of the integral: most of the deterministic methods like trapezoidal rule strongly depend on the dimension of the integral, because they use a grid to fill the space to compute the integral, and the grid grows exponentially with the dimensions.[5]

The above expression provides a statistical estimate of the error on the result, which is not a strict error bound; random sampling of the region may not uncover all the important features of the function, resulting in an underestimate of the error.

Example

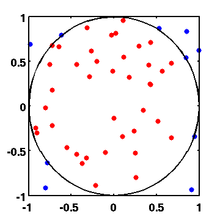

A paradigmatic example of a Monte Carlo integration is the estimation of π. Consider the function

and the set Ω = [−1,1] × [−1,1] with V = 4. Notice that

Thus, a crude way of calculating the value of π with Monte Carlo integration is to pick N random numbers on Ω and compute

In the figure the relative error is shown, following the expected scaling.

Wolfram Mathematica Example

The code below describes a process of integrating the function

using the Monte-Carlo method in Mathematica:

|

code:

|

Recursive stratified sampling

Recursive stratified sampling is a generalization of one-dimensional adaptive quadratures to multi-dimensional integrals. On each recursion step the integral and the error are estimated using a plain Monte Carlo algorithm. If the error estimate is larger than the required accuracy the integration volume is divided into sub-volumes and the procedure is recursively applied to sub-volumes.

The ordinary 'dividing by two' strategy does not work for multi-dimensions as the number of sub-volumes grows way too quickly to keep track. Instead one estimates along which dimension a subdivision should bring the most dividends and only subdivides the volume along this dimension.

The stratified sampling algorithm concentrates the sampling points in the regions where the variance of the function is largest thus reducing the grand variance and making the sampling more effective, as shown on the illustration.

The popular MISER routine implements a similar algorithm.

MISER Monte Carlo

The MISER algorithm is based on recursive stratified sampling. This technique aims to reduce the overall integration error by concentrating integration points in the regions of highest variance.[6]

The idea of stratified sampling begins with the observation that for two disjoint regions a and b with Monte Carlo estimates of the integral and and variances and , the variance Var(f) of the combined estimate

is given by,

It can be shown that this variance is minimized by distributing the points such that,

Hence the smallest error estimate is obtained by allocating sample points in proportion to the standard deviation of the function in each sub-region.

The MISER algorithm proceeds by bisecting the integration region along one coordinate axis to give two sub-regions at each step. The direction is chosen by examining all d possible bisections and selecting the one which will minimize the combined variance of the two sub-regions. The variance in the sub-regions is estimated by sampling with a fraction of the total number of points available to the current step. The same procedure is then repeated recursively for each of the two half-spaces from the best bisection. The remaining sample points are allocated to the sub-regions using the formula for Na and Nb. This recursive allocation of integration points continues down to a user-specified depth where each sub-region is integrated using a plain Monte Carlo estimate. These individual values and their error estimates are then combined upwards to give an overall result and an estimate of its error.

Importance sampling

VEGAS Monte Carlo

The VEGAS algorithm takes advantage of the information stored during the sampling, and uses it and importance sampling to efficiently estimate the integral I. It samples points from the probability distribution described by the function |f| so that the points are concentrated in the regions that make the largest contribution to the integral.

In general, if the Monte Carlo integral of f is sampled with points distributed according to a probability distribution described by the function g, we obtain an estimate:

with a corresponding variance,

If the probability distribution is chosen as

then it can be shown that the variance vanishes, and the error in the estimate will be zero. In practice it is not possible to sample from the exact distribution g for an arbitrary function, so importance sampling algorithms aim to produce efficient approximations to the desired distribution.

The VEGAS algorithm approximates the exact distribution by making a number of passes over the integration region which creates the histogram of the function f. Each histogram is used to define a sampling distribution for the next pass. Asymptotically this procedure converges to the desired distribution.[7] In order to avoid the number of histogram bins growing like Kd, the probability distribution is approximated by a separable function:

so that the number of bins required is only Kd. This is equivalent to locating the peaks of the function from the projections of the integrand onto the coordinate axes. The efficiency of VEGAS depends on the validity of this assumption. It is most efficient when the peaks of the integrand are well-localized. If an integrand can be rewritten in a form which is approximately separable this will increase the efficiency of integration with VEGAS.

VEGAS incorporates a number of additional features, and combines both stratified sampling and importance sampling.[7] The integration region is divided into a number of "boxes", with each box getting a fixed number of points (the goal is 2). Each box can then have a fractional number of bins, but if bins/box is less than two, Vegas switches to a kind variance reduction (rather than importance sampling).

This routines uses the VEGAS Monte Carlo algorithm to integrate the function f over the dim-dimensional hypercubic region defined by the lower and upper limits in the arrays xl and xu, each of size dim. The integration uses a fixed number of function calls. The result and its error estimate are based on a weighted average of independent samples.

The VEGAS algorithm computes a number of independent estimates of the integral internally, according to the iterations parameter described below, and returns their weighted average. Random sampling of the integrand can occasionally produce an estimate where the error is zero, particularly if the function is constant in some regions. An estimate with zero error causes the weighted average to break down and must be handled separately.

Metropolis–Hastings algorithm

Importance sampling provides a very important tool to perform Monte-Carlo integration.[3] The main result of importance sampling to this method is that the uniform sampling of is a particular case of a more generic choice, on which the samples are drawn from any distribution . The idea is that can be chosen to decrease the variance of the measurement QN.

Consider the following example where one would like to numerically integrate a gaussian function, centered at 0, with σ = 1, from −1000 to 1000. Naturally, if the samples are drawn uniformly on the interval [−1000, 1000], only a very small part of them would be significant to the integral. This can be improved by choosing a different distribution from where the samples are chosen from, for instance by sampling according to a gaussian distribution centered at 0, with σ = 1. Of course the "right" choice strongly depends on the integrand.

Formally, given a set of samples chosen from a distribution

the estimator for I is given by[3]

where

is the normalization. Notice that if the is a uniform distribution, this estimator is the same as the one introduced in introduction.

The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm is one of the most used algorithms to generate from ,[3] thus providing an efficient way of computing integrals.

See also

Notes

References

- R. E. Caflisch, Monte Carlo and quasi-Monte Carlo methods, Acta Numerica vol. 7, Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp. 1–49.

- S. Weinzierl, Introduction to Monte Carlo methods,

- W.H. Press, G.R. Farrar, Recursive Stratified Sampling for Multidimensional Monte Carlo Integration, Computers in Physics, v4 (1990).

- G.P. Lepage, A New Algorithm for Adaptive Multidimensional Integration, Journal of Computational Physics 27, 192-203, (1978)

- G.P. Lepage, VEGAS: An Adaptive Multi-dimensional Integration Program, Cornell preprint CLNS 80-447, March 1980

- J. M. Hammersley, D.C. Handscomb (1964) Monte Carlo Methods. Methuen. ISBN 0-416-52340-4

- Press, WH; Teukolsky, SA; Vetterling, WT; Flannery, BP (2007). Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8.

- Newman, MEJ; Barkema, GT (1999). Monte Carlo Methods in Statistical Physics. Clarendon Press.

- Robert, CP; Casella, G (2004). Monte Carlo Statistical Methods (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-1939-7.

External links

- Café math : Monte Carlo Integration : A blog article describing Monte Carlo integration (principle, hypothesis, confidence interval)

- Module for Monte Carlo Integration

- Internet Resources for Monte Carlo Integration

![{\displaystyle func[x\_]:={\frac {1}{1+{\text{Sinh}}[2*x]*({\text{Log}}[x])^{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/00f2eefa5602275a93f7f2743aec4dd69d5a2937)