Lobopodia: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 144.118.94.167 (talk) to last revision by Anomalocaris (HG) |

→Representative taxa: missing space |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

==Representative taxa== |

==Representative taxa== |

||

The better-known [[genus|genera]] include, for example, ''[[Aysheaia]]'', which was discovered among the Canadian [[Burgess Shale]] and which is the most similar of the Lobopoda in appearance to the modern velvet worms; a pair of appendages on the head have been considered precursors of today's antennae.{{Citation needed|date=September 2008}} ''[[Xenusion]]'' was apparently able to roll itself up, spines outward, giving insight into the defensive strategies of the Lobopoda. However, by far the most famous of the lobopod genera is ''[[Hallucigenia]]'', named on account of its bizarre appearance. It was originally reconstructed with long, stilt-like legs and mysterious fleshy dorsal protuberances, and was long considered a prime example of the way in which nature experimented with the most diverse and bizarre body designs during the Cambrian.<ref>{{WonderfulLife}}</ref> However, further discoveries showed that this reconstruction had placed the animal upside-down: interpreting the "stilts" as dorsal spines made it clear that the fleshy "dorsal" protuberances were actually legs. This second reconstruction also exchanged the front and rear ends of the creature, which further investigation showed to be erroneous.<ref>Further information and references: See ''[[Hallucigenia]]''</ref> The armoured lobopodian ''[[Diania]]'' is significant for having the most arthropod-like appendages. |

The better-known [[genus|genera]] include, for example, ''[[Aysheaia]]'', which was discovered among the Canadian [[Burgess Shale]] and which is the most similar of the Lobopoda in appearance to the modern velvet worms; a pair of appendages on the head have been considered precursors of today's antennae.{{Citation needed|date=September 2008}} ''[[Xenusion]]'' was apparently able to roll itself up, spines outward, giving insight into the defensive strategies of the Lobopoda. However, by far the most famous of the lobopod genera is ''[[Hallucigenia]]'', named on account of its bizarre appearance. It was originally reconstructed with long, stilt-like legs and mysterious fleshy dorsal protuberances, and was long considered a prime example of the way in which nature experimented with the most diverse and bizarre body designs during the Cambrian.<ref>{{WonderfulLife}}</ref> However, further discoveries showed that this reconstruction had placed the animal upside-down: interpreting the "stilts" as dorsal spines made it clear that the fleshy "dorsal" protuberances were actually legs. This second reconstruction also exchanged the front and rear ends of the creature, which further investigation showed to be erroneous.<ref>Further information and references: See ''[[Hallucigenia]]''</ref> The armoured lobopodian ''[[Diania]]'' is significant for having the most arthropod-like appendages. A long-legged taxon is known from the Carboniferous [[Mazon Creek]].<ref name="Haug2012" /> |

||

==Morphology== |

==Morphology== |

||

Revision as of 01:18, 24 July 2013

- For a type of cell projection see Pseudopod.

| Lobopodia Temporal range: The taxa Onychophora and Tardigrada survive to Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

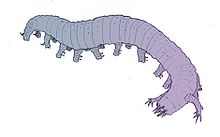

| Reconstruction of the lobopod Aysheaia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Superphylum: | Ecdysozoa (in part) |

| Groups included | |

Lobopodia is a group of poorly understood animals, which mostly fall into a stem group of arthropods. Their fossil range dates back to the Early Cambrian. Lobopods are segmented and typically bare legs with hooked claws on their ends.[2]

The oldest near-complete fossil lobopods date to the Lower Cambrian; some are also known from a Silurian Lagerstätte.[3] They resemble the modern onychophorans (velvet worms) in their worm-like body shape and numerous stub-legs. They differ in their possession of numerous dorsal armour plates, "sclerita", which often cover the entire body and head. Since they taper off into long, pointed spikes, these probably served a role in defence against predators.[citation needed] Individual sclerita are found among the so-called "small shelly fauna" (SSF) from the early Cambrian period.[2] The "lobopodia" group is considered to include these Cambrian forms in addition to the extant onychophorans.

Representative taxa

The better-known genera include, for example, Aysheaia, which was discovered among the Canadian Burgess Shale and which is the most similar of the Lobopoda in appearance to the modern velvet worms; a pair of appendages on the head have been considered precursors of today's antennae.[citation needed] Xenusion was apparently able to roll itself up, spines outward, giving insight into the defensive strategies of the Lobopoda. However, by far the most famous of the lobopod genera is Hallucigenia, named on account of its bizarre appearance. It was originally reconstructed with long, stilt-like legs and mysterious fleshy dorsal protuberances, and was long considered a prime example of the way in which nature experimented with the most diverse and bizarre body designs during the Cambrian.[4] However, further discoveries showed that this reconstruction had placed the animal upside-down: interpreting the "stilts" as dorsal spines made it clear that the fleshy "dorsal" protuberances were actually legs. This second reconstruction also exchanged the front and rear ends of the creature, which further investigation showed to be erroneous.[5] The armoured lobopodian Diania is significant for having the most arthropod-like appendages. A long-legged taxon is known from the Carboniferous Mazon Creek.[1]

Morphology

Most lobopods are in the order of inches in length, though tardigrades are ~0.1 to 1.5 millimeters long. They are annulated, although the annulation may be difficult to discern on account of their close spacing (~0.2mm) and low relief.[6] Lobopodia and their legs are circular in cross-section.[6] Their legs, technically called lobopods, are loosely conical in shape, tapering from the body to their clawed tips.[6] The longest and most robust legs are at the middle of the trunk, with those nearer the head and tail more spindly.[6] The claws are slightly curved. Their length is loosely proportional to the length of the leg to which they are attached.[6] The eyes are similar to those of modern arthropods as has been shown in Miraluolishania haikouensis (Liu et al., 2004).

The gut of lobopods is unusual in that it is straight, undifferentiated, and sometimes preserved in the fossil record in three dimensions. In some specimens the gut is found to be filled with sediment.[6] The gut consists of a central tube occupying the full length of the lobopod's trunk,[7] which doesn't change much in width - at least not in a systematic fashion. This may be surrounded by serially repeated[7] kidney-shaped diverticulae.[2] In some specimens, parts of the lobopod gut can be preserved in three dimensions. This cannot result from phosphatisation, which is usually responsible for 3-D gut preservation,[8] for the phosphate content of the guts is under 1%; the contents comprise quartz and muscovite.[6] The gut of the representative Paucipodia is variable in width, being widest at the centre of the body. Its position in the body cavity is only loosely fixed, so flexibility is possible.

Ecology

The way of life of the Cambrian Lobopodia is to a large extent unknown; some species were apparently carnivorous, feeding on other animals such as, for example, sponges (Porifera). Others apparently lived in close association with the enigmatic genus Eldonia.

Diversity

During the Cambrian lobopods displayed a substantial degree of biodiversity. However, only one species is known from each of the Ordovician and Silurian periods,[3][9] with a few more known from the Carboniferous (Mazon Creek).

Phylogeny

The lobopods are thought to be closely related to the arthropods; indeed, the arthropods may well have arisen from within the lobopods. They may be less closely related to the tardigrades; precise classification is still in flux.[2]

See also

The name Lobopodia is also used for lobose pseudopods, found among certain amoeboids.

References

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.066, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.066instead. - ^ a b c d Liu; Shu, Degan; Han, Jian; Zhang, Zhifei; Zhang, Xingliang (2007). "Origin, diversification, and relationships of Cambrian lobopods". Gondwana Research. 14 (1–2): 277. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2007.10.001. Cite error: The named reference "Liu2007" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1130/G23894A.1, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1130/G23894A.1instead. - ^ Template:WonderfulLife

- ^ Further information and references: See Hallucigenia

- ^ a b c d e f g Hou, Xian-Guang; Ma, Xiao-Ya; Zhao, Jie; Bergström, Jan (2004). "The lobopodian Paucipodia inermis from the Lower Cambrian Chengjiang fauna, Yunnan, China". Lethaia. 37 (3): 235. doi:10.1080/00241160410006555.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Jianni Liu, Degan Shu, Jian Han, Zhifei Zhang, and Xingliang Zhang (2006). "A large xenusiid lobopod with complex appendages from the Lower Cambrian Chengjiang Lagerstätte" (PDF). Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 51 (2): 215–222. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1666.2F0094-8373.282002.29028.3C0155:LGATIO.3E2.0.CO.3B2, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1666.2F0094-8373.282002.29028.3C0155:LGATIO.3E2.0.CO.3B2instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00860.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00860.xinstead.