Namibia: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

===German rule=== |

===German rule=== |

||

Namibia became a German colony in 1884 under [[Otto von Bismarck]] to forestall British encroachment and was known as [[German South-West Africa]] (''Deutsch-Südwestafrika'').<ref>{{cite web|title=German South West Africa|work=Encyclopædia Britannica|url=http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9036573/German-South-West-Africa|accessdate=15 April 2008}}</ref> However, the Palgrave mission by the British governor in Cape Town had determined that only the natural deep-water harbour of [[Walvis Bay]] (Walfisch in German, Walvis in Afrikaans, Whale in English) was worth occupying – and this was annexed to the Cape province of British South Africa. From 1904 to 1907, the [[Herero people|Herero]] and the [[Nama people|Namaqua]] took up arms against the Germans and in the subsequent [[Herero and Namaqua genocide]], 10,000 Nama (half the population) and approximately 65,000 Hereros (about 80% of the population) were killed.<ref>Drechsler, Horst (1980). The actual number of deaths in the limited number of battles with the Germany Schutztruppe (expeditionary force) were limited, most of the deaths occurred after fighting had ended due to the extermination order issued by the German military governor Lotha von Trotha. A substantial minority of Herero crossed the Kalahari desert into the British colony of Bechuanaland (modern-day Botswana) where a small community continues to live in western Botswana near to border with Namibia ''Let us die fighting'', originally published (1966) under the title "Südwestafrika unter deutsche Kolonialherrschaft". Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.</ref><ref name=Adhikari/> The survivors, when finally released from detention, were subjected to a policy of dispossession, deportation, forced labour, racial segregation and discrimination in a system that in many ways anticipated apartheid. Most Africans were confined to so-called native territories, which later under South African rule post-1949 were turned into "homelands" (Bantustans). Indeed, some historians have speculated that the German genocide in Namibia was a model used by [[Nazism|Nazi]]s in [[the Holocaust]],<ref name=Madley/> but most scholars say that episode was not especially influential for the Nazis, who were children at the time.<ref>[http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1138299/The-Holocaust-Horrifying-secrets-Germanys-earliest-genocide-inside-Africas-Forbidden-Zone.html Namibia's German Genocide]. Dailymail.co.uk (2009-02-07). Retrieved on 2012-12-12.</ref> However, the father of Luftwaffe commander [[Hermann Göring]] was a one-time German colonial governor of Namibia and has a street named after him in Swakopmund.<ref name=Gerwarth/> The memory of genocide remains relevant to ethnic identity in independent Namibia and to relations with Germany.<ref>Reinhart Kössler, and Henning Melber, "Völkermord und Gedenken: Der Genozid an den Herero und Nama in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1904–1908," ("Genocide and memory: the genocide of the Herero and Nama in German South-West Africa, 1904–08") ''Jahrbuch zur Geschichte und Wirkung des Holocaust'' 2004: 37–75</ref> Until today Germany fails to take full responsibility for its colonial past. For one reason because as a consequence Germany would have to pay relatively high sums of money as a kind of compensation. This would also be a precedent for other colonial powers.<ref>{{cite web |title=Colonial shadows |author=Henning Melber |publisher=D+C Development and Cooperation/ dandc.eu |date=January 2013 |url=http://www.dandc.eu/en/article/germany-struggles-deal-colonial-past-atrocities-namibia}}</ref> |

Namibia became a German colony in 1884 under [[Otto von Bismarck]] to forestall British encroachment and was known as [[German South-West Africa]] (''Deutsch-Südwestafrika'').<ref>{{cite web|title=German South West Africa|work=Encyclopædia Britannica|url=http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9036573/German-South-West-Africa|accessdate=15 April 2008}}</ref> However, the Palgrave mission by the British governor in Cape Town had determined that only the natural deep-water harbour of [[Walvis Bay]] (Walfisch in German, Walvis in Afrikaans, Whale in English) was worth occupying – and this was annexed to the Cape province of British South Africa. From 1904 to 1907, the [[Herero people|Herero]] and the [[Nama people|Namaqua]] took up arms against the Germans and in the subsequent [[Herero and Namaqua genocide]], 10,000 Nama (half the population) and approximately 65,000 Hereros (about 80% of the population) were killed.<ref>Drechsler, Horst (1980). The actual number of deaths in the limited number of battles with the Germany Schutztruppe (expeditionary force) were limited, most of the deaths occurred after fighting had ended due to the extermination order issued by the German military governor Lotha von Trotha. A substantial minority of Herero crossed the Kalahari desert into the British colony of Bechuanaland (modern-day Botswana) where a small community continues to live in western Botswana near to border with Namibia ''Let us die fighting'', originally published (1966) under the title "Südwestafrika unter deutsche Kolonialherrschaft". Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.</ref><ref name=Adhikari/> The survivors, when finally released from detention, were subjected to a policy of dispossession, deportation, forced labour, racial segregation and discrimination in a system that in many ways anticipated apartheid. Most Africans were confined to so-called native territories, which later under South African rule post-1949 were turned into "homelands" (Bantustans). Indeed, some historians have speculated that the German genocide in Namibia was a model used by [[Nazism|Nazi]]s in [[the Holocaust]],<ref name=Madley/> but most scholars say that episode was not especially influential for the Nazis, who were children at the time.<ref>[http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1138299/The-Holocaust-Horrifying-secrets-Germanys-earliest-genocide-inside-Africas-Forbidden-Zone.html Namibia's German Genocide]. Dailymail.co.uk (2009-02-07). Retrieved on 2012-12-12.</ref> However, the father of Luftwaffe commander [[Hermann Göring]] was a one-time German colonial governor of Namibia and has a street named after him in Swakopmund.<ref name=Gerwarth/>Which is irrelevant, considering he left Namibia in 1890. The memory of genocide remains relevant to ethnic identity in independent Namibia and to relations with Germany.<ref>Reinhart Kössler, and Henning Melber, "Völkermord und Gedenken: Der Genozid an den Herero und Nama in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1904–1908," ("Genocide and memory: the genocide of the Herero and Nama in German South-West Africa, 1904–08") ''Jahrbuch zur Geschichte und Wirkung des Holocaust'' 2004: 37–75</ref> Until today Germany fails to take full responsibility for its colonial past. For one reason because as a consequence Germany would have to pay relatively high sums of money as a kind of compensation. This would also be a precedent for other colonial powers.<ref>{{cite web |title=Colonial shadows |author=Henning Melber |publisher=D+C Development and Cooperation/ dandc.eu |date=January 2013 |url=http://www.dandc.eu/en/article/germany-struggles-deal-colonial-past-atrocities-namibia}}</ref> See "pot calling kettle black" in terms of the British use of concentration camps earlier, <ref> "Using Barbaric Methods in South Africa: The British Concentration Camp during the Boer War" JR Jewell 2003 |

||

===South African rule and the struggle for independence=== |

===South African rule and the struggle for independence=== |

||

Revision as of 12:53, 31 July 2013

Republic of Namibia | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Unity, Liberty, Justice" | |

| Anthem: Namibia, Land of the Brave | |

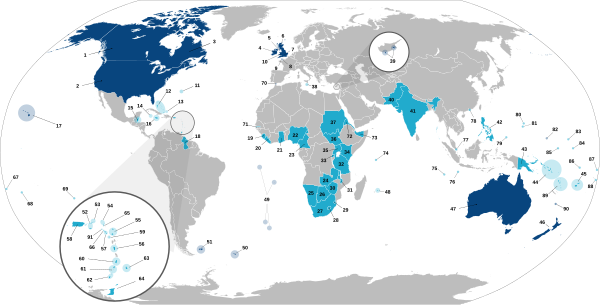

Location of Namibia (dark blue) – in Africa (light blue & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Windhoek |

| Official languages | English |

| Recognised regional languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2000) | |

| Demonym(s) | Namibian |

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic |

| Hifikepunye Pohamba | |

| Hage Geingob | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| National Council | |

| National Assembly | |

| Independence | |

• from South Africa | 21 March 1990 |

| 12 March 1990 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 825,418 km2 (318,696 sq mi) (34th) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2011 census | 2,100,000[1] |

• Density | 2.54/km2 (6.6/sq mi) (235th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2013 estimate |

• Total | $17.737 billion[2] |

• Per capita | $8,160[2] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2013 estimate |

• Total | $12.868 billion[2] |

• Per capita | $5,920[2] |

| Gini (2004) | 63.9[3] very high inequality (1st) |

| HDI (2013) | medium (128th) |

| Currency | Namibian dollar (NAD) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (WAT) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (WAST) |

| Drives on | Left |

| Calling code | +264 |

| ISO 3166 code | NA |

| Internet TLD | .na |

Namibia /nəˈmɪbiə/, officially the Republic of Namibia (Template:Lang-af; German: ⓘ), is a country in southern Africa whose western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Angola and Zambia to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and east. Although it does not border with Zimbabwe, less than 200 metres of riverbed (essentially the Zambia/Botswana border) separates them at their closest points. It gained independence from South Africa on 21 March 1990, following the Namibian War of Independence. Its capital and largest city is Windhoek. Namibia is a member state of the United Nations (UN), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the African Union (AU), and the Commonwealth of Nations.

The dry lands of Namibia were inhabited since early times by Bushmen, Damara, and Namaqua, and since about the 14th century AD by immigrating Bantu who came with the Bantu expansion. It became a German Imperial protectorate in 1884 and remained a German colony until the end of World War I. In 1920, the League of Nations mandated the country to South Africa, which imposed its laws and, from 1948, its apartheid policy.

Uprisings and demands by African leaders led the UN to assume direct responsibility over the territory. It recognised the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) as the official representative of the Namibian people in 1973. Namibia, however, remained under South African administration during this time as South-West Africa. Following internal violence, South Africa installed an interim administration in Namibia in 1985. Namibia obtained full independence from South Africa in 1990, with the exception of Walvis Bay and the Penguin Islands, which remained under South African control until 1994.

Namibia has a population of 2.1 million people and a stable multi-party parliamentary democracy. Agriculture, herding, tourism and the mining industry – including mining for gem diamonds, uranium, gold, silver, and base metals – form the backbone of Namibia's economy. Given the presence of the arid Namib Desert, it is one of the least densely populated countries in the world. Approximately half the population live below the international poverty line, and the nation has suffered heavily from the effects of HIV/AIDS, with 15% of the adult population infected with HIV in 2007.

History

The name of the country is derived from the Namib Desert, considered to be the oldest desert in the world.[5] Before its independence in 1990, the area was known first as German South-West Africa (Deutsch-Südwestafrika), then as South-West Africa, reflecting the colonial occupation by the Germans and the South Africans (technically on behalf of the British crown reflecting South Africa's dominion status within the British Empire).

Pre-colonial period

The dry lands of Namibia were inhabited since early times by Bushmen, Damara, Nama, and since about the 14th century AD, by immigrating Bantu who came with the Bantu expansion from central Africa. From the late 18th century onwards, Orlam clans from the Cape Colony crossed the Orange River and moved into the area that today is southern Namibia.[6] Their encounters with the nomadic Nama tribes were largely peaceful. The missionaries accompanying the Orlams were well received by them,[7] the right to use waterholes and grazing was granted against an annual payment.[8] On their way further northwards, however, the Orlams encountered clans of the Herero tribe at Windhoek, Gobabis, and Okahandja which were less accommodating. The Nama-Herero War broke out in 1880, with hostilities ebbing only when Imperial Germany deployed troops to the contested places and cemented the status quo between Nama, Orlams, and Herero.[9]

The first Europeans to disembark and explore the region were the Portuguese navigators Diogo Cão in 1485 and Bartolomeu Dias in 1486; still the region was not claimed by the Portuguese crown. However, like most of Sub-Saharan Africa, Namibia was not extensively explored by Europeans until the 19th century, when traders and settlers arrived, principally from Germany and Sweden. In the late 19th century Dorsland trekkers crossed the area on their way from the Transvaal to Angola. Some of them settled in Namibia instead of continuing their journey, even more returned to South-West African territory after the Portuguese tried to convert them to Catholicism and forbade their language at schools.[10]

German rule

Namibia became a German colony in 1884 under Otto von Bismarck to forestall British encroachment and was known as German South-West Africa (Deutsch-Südwestafrika).[11] However, the Palgrave mission by the British governor in Cape Town had determined that only the natural deep-water harbour of Walvis Bay (Walfisch in German, Walvis in Afrikaans, Whale in English) was worth occupying – and this was annexed to the Cape province of British South Africa. From 1904 to 1907, the Herero and the Namaqua took up arms against the Germans and in the subsequent Herero and Namaqua genocide, 10,000 Nama (half the population) and approximately 65,000 Hereros (about 80% of the population) were killed.[12][13] The survivors, when finally released from detention, were subjected to a policy of dispossession, deportation, forced labour, racial segregation and discrimination in a system that in many ways anticipated apartheid. Most Africans were confined to so-called native territories, which later under South African rule post-1949 were turned into "homelands" (Bantustans). Indeed, some historians have speculated that the German genocide in Namibia was a model used by Nazis in the Holocaust,[14] but most scholars say that episode was not especially influential for the Nazis, who were children at the time.[15] However, the father of Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring was a one-time German colonial governor of Namibia and has a street named after him in Swakopmund.[16]Which is irrelevant, considering he left Namibia in 1890. The memory of genocide remains relevant to ethnic identity in independent Namibia and to relations with Germany.[17] Until today Germany fails to take full responsibility for its colonial past. For one reason because as a consequence Germany would have to pay relatively high sums of money as a kind of compensation. This would also be a precedent for other colonial powers.[18] See "pot calling kettle black" in terms of the British use of concentration camps earlier, Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).

In response to the 1966 ruling by the International Court of Justice, South-West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO) military wing, People's Liberation Army of Namibia, a guerrilla group began their armed struggle for independence,[19] but it was not until 1988 that South Africa agreed to end its occupation[20] of Namibia, in accordance with a UN peace plan for the entire region. During the South African occupation of Namibia, white commercial farmers, most of whom came as settlers from South Africa and represented 0.2% of the national population, owned 74% of arable land.[21] Outside the central-southern area of Namibia (known as the "Police Zone" since the German era and which contained the main towns, industries, mines and best arable land), the country was divided into "homelands", the version of South African bantustan applied to Namibia, although only a few were actually established due to non-cooperation by most indigenous Namibians.

After many unsuccessful attempts by the UN to persuade South Africa to agree to the implementation of UN Resolution 435, which had been adopted by the UN Security Council in 1978 as the internationally agreed decolonisation plan for Namibia, transition to independence finally started in 1988 under the tripartite diplomatic agreement between South Africa, Angola and Cuba, with the USSR and the USA as observers, under which South Africa agreed to withdraw and demobilise its forces in Namibia. As a result, Cuba agreed to pull back its troops in southern Angola sent to support the MPLA in its war for control of Angola with UNITA. A combined UN civilian and peace-keeping force under Finnish diplomat Martti Ahtisaari supervised the military withdrawals, the return of SWAPO exiles and the holding of Namibia's first one-person one-vote election for a constituent assembly in October 1989. This was won by SWAPO although it did not gain the two-thirds majority it had hoped for; the South African-backed Democratic Turnhalle Alliance (DTA) became the official opposition.

Following the adoption of the Namibian Constitution, including entrenched protection for human rights, compensation for state expropriations of private property, an independent judiciary and an executive presidency (the constituent assembly became the national assembly), the country officially became independent on 21 March 1990. Sam Nujoma was sworn in as the first President of Namibia watched by Nelson Mandela (who had been released from prison the previous month) and representatives from 147 countries, including 20 heads of state.[22] Walvis Bay was ceded to Namibia in 1994 upon the end of Apartheid in South Africa.[citation needed]

After independence

Since independence Namibia has successfully completed the transition from white minority apartheid rule to parliamentary democracy. Multiparty democracy was introduced and has been maintained, with local, regional and national elections held regularly. Several registered political parties are active and represented in the National Assembly, although Swapo Party has won every election since independence.[23] The transition from the 15-year rule of President Sam Nujoma to his successor, Hifikepunye Pohamba in 2005 went smoothly.[24]

Namibian government has promoted a policy of national reconciliation and issued an amnesty for those who had fought on either side during the liberation war. The civil war in Angola had a limited impact on Namibians living in the north of the country. In 1998, Namibia Defence Force (NDF) troops were sent to the Democratic Republic of the Congo as part of a Southern African Development Community (SADC) contingent. In August 1999, a secessionist attempt in the northeastern Caprivi region was successfully quashed.[24]

Politics and government

The politics of Namibia takes place in a framework of a presidential representative democratic republic, whereby the president of Namibia is elected to a five-year term and is both the head of state and the head of government.[25]

The Constitution of Namibia guarantees the separation of powers:[26]

- Executive power is exercised by the President and Cabinet.

- Legislature: Namibia has a bicameral Parliament with the National Assembly as lower house, and the National Council the upper house.

- Judiciary: Namibia has a system of courts that interpret and apply the law in the name of the state.

While the constitution envisaged a multi-party system for Namibia's government, The SWAPO party has been dominant since independence in 1990.[27]

Foreign relations

Namibia follows a largely independent foreign policy, with lingering affiliations with states that aided the independence struggle, including Libya and Cuba. With a small army and a fragile economy, the Namibian Government's principal foreign policy concern is developing strengthened ties within the Southern African region. A dynamic member of the Southern African Development Community, Namibia is a vocal advocate for greater regional integration. Namibia became the 160th member of the UN on 23 April 1990. On its independence it became the fiftieth member of the Commonwealth of Nations.[28]

Military

Namibia does not have any enemies in the region but consistently spends more on its military than all of its neighbours, except Angola. Military expenditure rose from 2.7% of GDP in 2000 to 3.7% in 2009, and the arrival of 12 Chengdu J-7 Airguard jets in 2006 and 2008 made Namibia for a short time one of the top arms importers in Sub-Saharan Africa.[29]

The constitution of Namibia defined the role of the military as "defending the territory and national interests." Namibia formed the Namibian Defence Force (NDF), comprising former enemies in a 23-year bush war: the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) and South West African Territorial Force (SWATF). The British formulated the plan for integrating these forces and began training the NDF, which consists of a small headquarters and five battalions.

The United Nations Transitional Assistance Group (UNTAG)'s Kenyan infantry battalion remained in Namibia for three months after independence to help train the NDF and to stabilise the north. According to the Namibian Defence Ministry, enlistments of both men and women will number no more than 7,500.

Geography and climate

At 825,418 km2 (318,696 sq mi),[30] Namibia is the world's thirty-fourth largest country (after Venezuela). It lies mostly between latitudes 17° and 29°S (a small area is north of 17°), and longitudes 11° and 26°E.

Being situated between the Namib and the Kalahari deserts, Namibia is the country with the least rainfall in sub-Saharan Africa.[31]

Administrative division

Namibia is divided into 13 regions and subdivided into 107 constituencies. The administrative division of Namibia is tabled by Delimitation Commissions and accepted or declined by the National Assembly. Since state foundation three Delimitation Commissions have delivered their work, the last one in 2002 under the chairmanship of Peter Shivute.[32] The fourth Delimitation Commission was formed in January 2013, it is supposed to deliver their recommendation at the end of June for the preparation of the 2014 elections.[33]

Regional councillors are directly elected through secret ballots (regional elections) by the inhabitants of their constituencies.[34]

Geographical areas

The Namibian landscape consists generally of five geographical areas, each with characteristic abiotic conditions and vegetation with some variation within and overlap between them: the Central Plateau, the Namib Desert, the Great Escarpment, the Bushveld, and the Kalahari Desert.

Central Plateau

The Central Plateau runs from north to south, bordered by the Skeleton Coast to the northwest, the Namib Desert and its coastal plains to the southwest, the Orange River to the south, and the Kalahari Desert to the east. The Central Plateau is home to the highest point in Namibia at Königstein elevation 2,606 meters (8,550 ft).[35] Within the wide, flat Central Plateau is the majority of Namibia’s population and economic activity. Windhoek, the nation’s capital, is located here, as well as most of the arable land. Although arable land accounts for only 1% of Namibia, nearly half of the population is employed in agriculture.[36]

The abiotic conditions here are similar to those found along the Escarpment; however the topographic complexity is reduced. Summer temperatures in the area can reach 40 °C (104 °F), and frosts are common in the winter.

Namib Desert

The Namib Desert is a broad expanse of hyper-arid gravel plains and dunes that stretches along Namibia's entire coastline. It varies between 100 to many hundreds of kilometres in width. Areas within the Namib include the Skeleton Coast and the Kaokoveld in the north and the extensive Namib Sand Sea along the central coast.[37] The sands that make up the sand sea result from processes of erosion that take place in the Orange River valley and areas further to the south. As sand-laden waters drop their suspended loads into the Atlantic, onshore currents deposit them along the shore. The prevailing south west winds then pick up and redeposit the sand in the form of massive dunes in the widespread sand sea, forming the largest sand dunes in the world. In areas where the supply of sand is reduced because of the inability of the sand to cross riverbeds, the winds also scour the land to form large gravel plains. In many areas of the Namib Desert there is little vegetation aside from lichens found in the gravel plains and in dry river beds where plants can access subterranean water.

Great Escarpment

The Great Escarpment swiftly rises to over 2,000 meters (6,562 ft). Average temperatures and temperature ranges increase further inland from the cold Atlantic waters, while the lingering coastal fogs slowly diminish. Although the area is rocky with poorly developed soils, it is nonetheless significantly more productive than the Namib Desert. As summer winds are forced over the Escarpment, moisture is extracted as precipitation.[38] The water, along with rapidly changing topography, is responsible for the creation of microhabitats which offer a wide range of organisms, many of them endemic. Vegetation along the escarpment varies in both form and density, with community structure ranging from dense woodlands to more shrubby areas with scattered trees. A number of Acacia species are found here, as well as grasses and other shrubby vegetation.

Bushveld

The Bushveld is found in north eastern Namibia along the Angolan border and in the Caprivi Strip which is the vestige of a narrow corridor demarcated for the German Empire to access the Zambezi River. The area receives a significantly greater amount of precipitation than the rest of the country, averaging around 400 mm (15.7 in) per year. Temperatures are also cooler and more moderate, with approximate seasonal variations of between 10 and 30 °C (50 and 86 °F). The area is generally flat and the soils sandy, limiting their ability to retain water.[39] Located adjacent to the Bushveld in north-central Namibia is one of nature’s most spectacular features: the Etosha Pan. For most of the year it is a dry, saline wasteland, but during the wet season, it forms a shallow lake covering more than 6,000 square kilometres (2,317 sq mi). The area is ecologically important and vital to the huge numbers of birds and animals from the surrounding savannah that gather in the region as summer drought forces them to the scattered waterholes that ring the pan. The Bushveld area has been demarcated by the World Wildlife Fund as part of the Angolan Mopane woodlands ecoregion, which extends north across the Cunene River into neighbouring Angola.

Kalahari Desert

The Kalahari Desert, an arid region shared with South Africa and Botswana, is one of Namibia’s well-known geographical features. The Kalahari, while popularly known as a desert, has a variety of localized environments, including some verdant and technically non-desert areas. One of these, known as the Succulent Karoo, is home to over 5,000 species of plants, nearly half of them endemic; fully one-third of the world’s succulents are found in the Karoo.[citation needed]

The reason behind this high productivity and endemism may be the relatively stable nature of precipitation.[40] The Karoo does not experience drought on a regular basis, so even though the area is technically desert, regular winter rains provide enough moisture to support the region’s interesting plant community. Another feature of the Kalahari, indeed many parts of Namibia, are inselbergs, isolated mountains that create micro-climates and habitat for organisms not adapted to life in the surrounding desert matrix.

Coastal Desert

Namibia’s Coastal Desert is one of the oldest deserts in the world. Its sand dunes, created by the strong onshore winds, are the highest in the world.[41]

The Namib Desert and the Namib-Naukluft National Park are located here. The Namibian coastal deserts are one of the richest sources of diamonds on earth. The area is divided into the northern Skeleton Coast and the southern Diamond Coast. Because of the location of the shoreline — at the point where the Atlantic's cold water reaches Africa — there is often extremely dense fog.[42]

Sandy beach composes 54% of the shoreline, and mixed sand and rock form another 28%. Only 16% of the total length is rocky shoreline. The coastal plains are "dune fields", gravel plains covered with lichen and some scattered salt pans. Near the coast there are areas where the dunes are vegetated with hammocks.[43] Namibia has rich coastal and marine resources that remain largely unexplored.[44]

Weather and climate

Namibia extends from 17S to 25S: climatically the range of the sub-Tropical High Pressure Belt, arid is the overall climate description descending from the Sub-Humid (mean rain above 500mm) through Semi-Arid between 300 and 500mm (embracing most of the waterless Kalahari) and Arid from 150mm to 300mm (these three regions are inland from the western escarpment) to the Hyper-Arid coastal plain with less than a 100mm mean. An intermediate: Severely Arid, embracing the pre-Namib, covers the 100 to 150mm range. Variability is the Arid climate hallmark for both rainfall and temperature. Rainfall means, in particular, give a range from below 100mm per annum for the length of the Namib Desert,to 700 per annum for Katima Mulilo at the eastern end of the Caprivi; variability ranges from zero rain (no rain at all) to 800mm plus recorded, occurring during a bountiful season. Although the core of the rainy season: January to March provides some 70 per cent of the overall, while associated with the November, December and April overall measures adding as much as another 25 per cent (mid-90 per cent of the annual), rain is possible across the outlying months: September, October and May, the contribution is less than 5 per cent on average. Variability can see the seasonal spread vary from excessively wet possible months to rainless core months. It is only across the Kavango and Caprivi rainfall stations that the core month minimum denotes at least a day or two of rain. The extreme southwest, typically the Rosh Pinah stations, enjoys both a summer and winter regime, though the most intense falls rarely exceed 10mm in a day. Winter rains have been predictable across the southern Karas and Hardap regions providing moisture for the overall environment. The advent of a changing climate has seen a depletion of the regular winter input, while increased intensities during the March–April months (thundery showers) have been recorded. Temperature maxima are limited by the overall elevation of the entire region: only in the far south, Warmbad for instance, are mid-40C maxima recorded.[45]

Typically the sub-Tropical High Pressure Belt, with frequent clear skies, provides more than 300 days of sunshine per year. It is situated at the southern edge of the tropics; the Tropic of Capricorn cuts the country about in half. The winter (June – August) is generally dry, both rainy seasons occur in summer, the small rainy season between September and November, the big one between February and April.[46] Humidity is low, and average rainfall varies from almost zero in the coastal desert to more than 600mm in the Caprivi Strip. Rainfall is however highly variable, and droughts are common.[47] The last[update] bad rainy season with rainfall far below the annual average occurred in summer 2006/07.[48]

Weather and climate in the coastal area are dominated by the cold, north-flowing Benguela current of the Atlantic Ocean which accounts for very low precipitation (50 mm per year or less), frequent dense fog, and overall lower temperatures than in the rest of the country.[47] In Winter, occasionally a condition known as Bergwind (Template:Lang-de) or Oosweer (Template:Lang-af) occurs, a hot dry wind blowing from the inland to the coast. As the area behind the coast is a desert, these winds can develop into sand storms with sand deposits in the Atlantic Ocean visible on satellite images.[49]

The Central Plateau and Kalahari areas have wide diurnal temperature ranges of up to 30C.[47]

Efundja, the annual flooding of the northern parts of the country, often causes not only damage to infrastructure but loss of life.[50] The rains that cause these floods originate in Angola, flow into Namibia's Cuvelai basin, and fill the Oshanas (Oshiwambo: flood plains) there. The worst floods so far[update] occurred in March 2011 and displaced 21,000 people.[51]

Economy

Namibia’s economy is tied closely to South Africa’s due to their shared history.[52][53] The largest economic sectors are mining (10.4% of the gross domestic product in 2009), agriculture (5.0%), manufacturing (13.5%), and tourism.[54]

Namibia has a highly developed banking sector with modern infrastructure, such as Online Banking, Cellphone Banking, etc. The Bank of Namibia (BoN) is the central bank of Namibia responsible to perform all other functions ordinarily performed by a central bank. There are four BoN authorised commercial banks in Namibia: Bank Windhoek, First National Bank, Nedbank & Standard Bank.[55]

According to the Namibia Labour Force Survey Report 2012, conducted by the Namibia Statistics Agency, the country's unemployment rate is 27.4%. "Strict unemployment" (people actively seeking a full-time job) stood at 20.2% in 2000, 21.9% in 2004 and spiraled to 29.4% in 2008. Under a broader definition (including people that have given up searching for employment) unemployment rose to 36.7% in 2004. This estimate considers people in the informal economy as employed. Labour and Social Welfare Minister Immanuel Ngatjizeko praised the 2008 study as "by far superior in scope and quality to any that has been available previously",[56] but its methodology has also received criticism.[57]

In 2004 a labour act was passed to protect people from job discrimination stemming from pregnancy and HIV/AIDS status. In early 2010 the Government tender board announced that "henceforth 100 per cent of all unskilled and semi-skilled labour must be sourced, without exception, from within Namibia".[58]

In 2013, global business and financial news provider, Bloomberg, named Namibia the top emerging market economy in Africa and the 13th best in the world. Only four African countries made the Top 20 Emerging Markets list in the March 2013 issue of Bloomberg Markets magazine, and Namibia was rated ahead of Morocco (19th), South Africa (15th) and Zambia (14th). Worldwide, Namibia also fared better than Hungary, Brazil and Mexico. Bloomberg Markets magazine ranked the top 20 based on more than a dozen criteria. The data came from Bloomberg's own financial-market statistics, IMF forecasts and the World Bank. The countries were also rated on areas of particular interest to foreign investors: the ease of doing business, the perceived level of corruption and economic freedom. Namibia is also classified as an Upper Middle Income country by the World Bank, and ranks 87th out of 185 economies in terms of "Ease of Doing Business".

Transportation

Despite the remote nature of much of the country, Namibia has seaports, airports, highways, and railways (narrow-gauge). The country seeks to become a regional transportation hub; it has an important seaport and several landlocked neighbours. The Central Plateau already serves as a transportation corridor from the more densely populated north to South Africa, the source of four-fifths of Namibia’s imports.[36]

Agriculture

About half of the population depends on agriculture (largely subsistence agriculture) for its livelihood, but Namibia must still import some of its food. Although per capita GDP is five times the per capita GDP of Africa's poorest countries, the majority of Namibia's people live in rural areas and exist on a subsistence way of life. Namibia has one of the highest rates of income inequality in the world, due in part to the fact that there is an urban economy and a more rural cash-less economy. The inequality figures thus take into account people who do not actually rely on the formal economy for their survival.

About 4,000, mostly white, commercial farmers own almost half of Namibia's arable land.[59] The governments of Germany and Britain will finance Namibia's land reform process, as Namibia plans to start expropriating land from white farmers to resettle landless black Namibians.[60]

Agreement has been reached on the privatisation of several more enterprises in coming years, with hopes that this will stimulate much needed foreign investment. However, reinvestment of environmentally derived capital has hobbled Namibian per capita income.[61] One of the fastest growing areas of economic development in Namibia is the growth of wildlife conservancies. These conservancies are particularly important to the rural generally unemployed population.

An aquifer called "Ohangwena II" has been discovered, capable of supplying the 800,000 people in the North for 400 years.[62] Experts estimate that Namibia has 7720 km3 of underground water.[63][64]

Mining and electricity

Providing 25% of Namibia's revenue, mining is the single most important contributor to the economy.[65] Namibia is the fourth largest exporter of non-fuel minerals in Africa and the world's fourth largest producer of uranium. There has been significant investment in uranium mining and Namibia is set to become the largest exporter of uranium by 2015.[66] Rich alluvial diamond deposits make Namibia a primary source for gem-quality diamonds.[67] While Namibia is known predominantly for its gem diamond and uranium deposits, a number of other minerals are extracted industrially such as lead, tungsten, gold, tin, fluorspar, manganese, marble, copper and zinc. There are offshore gas deposits in the Atlantic Ocean that are planned to be extracted in the future.[54] According to "The Diamond Investigation", a book about the global diamond market, from 1978, De Beers, the largest diamond company, bought most of the Namibian diamonds, and would continue to do so, because "whatever government eventually comes to power they will need this revenue to survive".[68]

Domestic supply voltage is 220V AC. Electricity is generated mainly by thermal and hydroelectric power plants. Non-conventional methods of electricity generation also play some role. Encouraged by the rich uranium deposits the Namibian government plans to erect its first nuclear power station by 2018, also uranium enrichment is envisaged to happen locally.[69]

Tourism

Tourism is a major contributor (14.5%) to Namibia's GDP, creating tens of thousands of jobs (18.2% of all employment) directly or indirectly and servicing over a million tourists per annum.[70] The country is among the prime destinations in Africa and is known for ecotourism which features Namibia's extensive wildlife.[71]

There are many lodges and reserves to accommodate eco-tourists. Sport Hunting is also a large, and growing component of the Namibian economy, accounting for 14% of total tourism in the year 2000, or $19.6 million US dollars, with Namibia boasting numerous species sought after by international sport hunters.[72] In addition, extreme sports such as sandboarding, skydiving and 4x4ing have become popular, and many cities have companies that provide tours. The most visited places include the Caprivi Strip, Fish River Canyon, Sossusvlei, the Skeleton Coast Park, Sesriem, Etosha Pan and the coastal towns of Swakopmund, Walvis Bay and Lüderitz.[73]

Taxation and cost of living in Namibia

Cost of living in Namibia is relatively high because most of the goods including cereals need to be imported. Business monopoly in some sectors causes higher profit bookings and further raising of prices. Its capital city, Windhoek is currently ranked as the 150th most expensive place in the world for expatriates to live.[74]

Personal income tax is applicable to total taxable income of an individual and all individuals are taxed at progressive marginal rates over a series of income brackets. While the Value added tax (VAT) is applicable to most of the commodities and services.[75]

Demographics

Namibia has the second-lowest population density of any sovereign country, after Mongolia.[76] The majority of the Namibian population is of Bantu-speaking origin – mostly of the Ovambo ethnicity, which forms about half of the population – residing mainly in the north of the country, although many are now resident in towns throughout Namibia. Other ethnic groups are the Herero and Himba people, who speak a similar language, and the Damara, who speak the same "click" language as the Nama.

In addition to the Bantu majority, there are large groups of Khoisan (such as Nama and Bushmen), who are descendants of the original inhabitants of Southern Africa. The country also contains some descendants of refugees from Angola. There are also two smaller groups of people with mixed racial origins, called "Coloureds" and "Basters", who together make up 6.6% (with the Coloureds outnumbering the Basters two to one). There is a large Chinese minority in Namibia.[77]

Whites (mainly of Afrikaner, German, British and Portuguese) make up about 6.4% of the population; they form the second-largest population of European ancestry, both in terms of percentage and actual numbers, in Sub-Saharan Africa after that of South Africa.[78] Most Namibian whites and nearly all those of mixed race speak Afrikaans and share similar origins, culture, and religion as the white and coloured populations of South Africa. A smaller proportion of whites (around 30,000) trace their family origins directly back to German colonial settlers and maintain German cultural and educational institutions. Nearly all Portuguese settlers came to the country from the former Portuguese colony of Angola.[79] The 1960 census reported 526,004 persons in what was then South-West Africa, including 73,464 whites (14%).[80]

Namibia conducts a census every ten years. After independence the first Population and Housing Census was carried out in 1991, further rounds followed in 2001 and 2011.[81] The data collection method is to count every person resident in Namibia on the census reference night, wherever they happen to be. This is called the de facto method.[82] For enumeration purposes the country is demarcated into 4,042 enumeration areas. These areas do not overlap with constituency boundaries in order to get reliable data for election purposes as well.[83]

The 2011 Population and Housing Census counted 2,113,077 inhabitants of Namibia. Between 2001 and 2011 the annual population growth was 1.4%, down from 2.6% in the previous ten–year period.[84]

Largest cities

Template:Largest cities of Namibia

Religion

The Christian community makes up 80%–90% of the population of Namibia, with at least 50% of these Lutheran. 10%–20% of the population hold indigenous beliefs.[78]

Missionary work during the 1800s drew many Namibians to Christianity. While most Namibian Christians are Lutheran, there also are Roman Catholic, Methodist, Anglican, African Methodist Episcopal, Dutch Reformed, Rhenish Christians, and Mormons (the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints).

There are some Jewish people.[85]

Language

The official language is English. Until 1990, German and Afrikaans were also official languages. Long before Namibia's independence from South Africa, SWAPO had decided that the country should become officially monolingual, consciously choosing this approach in contrast to that of its neighbour South Africa (which granted all 11 of its major languages official status), which was regarded as "a deliberate policy of ethnolinguistic fragmentation."[86] Consequently, English became the sole official language of Namibia. Some other languages have received semi-official recognition by being allowed as medium of instruction in primary schools.

The northern majority of Namibians speak Oshiwambo as their first language, whereas the most widely understood and spoken language is Afrikaans. Among the younger generation, the most widely understood languages are English and Afrikaans. Both Afrikaans and English are used primarily as a second language reserved for public communication, but small first-language groups exist throughout the country.

While the official language is English, most of the white population speaks either German or Afrikaans. Even today, 90 years after the end of the German colonial era, the German language plays a leading role as a commercial language. Afrikaans is spoken by 60% of the white community, German is spoken by 32%, English is spoken by 7% and Portuguese by 1%.[78] Geographical proximity to Portuguese-speaking Angola explains the relatively high number of lusophones; in 2011 these were estimated to be 100,000, or 4–5% of the total population.[87]

Health

Life expectancy at birth is estimated to be 52.2 years in 2012 – among the lowest in the world.[88] The AIDS epidemic is a large problem in Namibia. Though its rate of infection is substantially lower than that of its eastern neighbour, Botswana, approximately 13.1% of the adult population is[update] infected with HIV.[89] In 2001, there were an estimated 210,000 people living with HIV/AIDS, and the estimated death toll in 2003 was 16,000. According to the 2011 UNAIDS Report, the epidemic in Namibia "appears to be leveling off."[90] As the HIV/AIDS epidemic has reduced the working-aged population, the number of orphans has increased. It falls to the government to provide education, food, shelter and clothing for these orphans.[91]

The malaria problem seems to be compounded by the AIDS epidemic. Research has shown that in Namibia the risk of contracting malaria is 14.5% greater if a person is also infected with HIV. The risk of death from malaria is also raised by approximately 50% with a concurrent HIV infection.[92] Given infection rates this large, as well as a looming malaria problem, it may be very difficult for the government to deal with both the medical and economic impacts of this epidemic. The country had only 598 physicians in 2002.[93]

Culture

Education

Namibia has compulsory free education for 10 years between the ages of 6 and 16. Grades 1–7 are primary level, grades 8–12 secondary. In 1998, there were 400,325 Namibian students in primary school and 115,237 students in secondary schools. The pupil-teacher ratio in 1999 was estimated at 32:1, with about 8% of the GDP being spent on education.[94] Curriculum development, educational research, and professional development of teachers is centrally organised by the National Institute for Educational Development (NIED) in Okahandja.[95]

Most schools in Namibia are state-run, but a few private schools are also part of the country's education system. There are four teacher training colleges, three colleges of agriculture, a police training college, a Polytechnic at university level, and a National University.

Communal Wildlife Conservancies

Namibia is one of few countries in the world to specifically address conservation and protection of natural resources in its constitution.[96] Article 95 states, "The State shall actively promote and maintain the welfare of the people by adopting international policies aimed at the following: maintenance of ecosystems, essential ecological processes, and biological diversity of Namibia, and utilisation of living natural resources on a sustainable basis for the benefit of all Namibians, both present and future."[96]

In 1993, the newly formed government of Namibia received funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through its Living in a Finite Environment (LIFE) Project.[97] The Ministry of Environment and Tourism with the financial support from organisations such as USAID, Endangered Wildlife Trust, WWF, and Canadian Ambassador's Fund, together form a Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) support structure. The main goal of this project is promote sustainable natural resource management by giving local communities rights to wildlife management and tourism.[98]

Sport

The most popular sport in Namibia is football. The Namibia national football team qualified for the 2008 Africa Cup of Nations but has yet to qualify for any World Cups. However, the most successful national team is the Namibian rugby team, having competed in four separate World Cups. Namibia were participants in the 1999, 2003, 2007 and 2011 Rugby World Cups. Cricket is also popular, with the national side having played in the 2003 Cricket World Cup.

Inline hockey was first played in 1995 and has also become more and more popular in the last years. The Women's inline hockey National Team participated in the 2008 FIRS World Championships. Namibia is the home for one of the toughest footraces in the world, the Namibian ultra marathon. The most famous athlete from Namibia is certainly Frankie Fredericks, sprinter (100 and 200 m). He won four Olympic silver medals (1992, 1996) and also has medals from several World Athletics Championships. He is also known for humanitarian activities in Namibia and further.

The Swakopmund Skydiving Club in Swakopmund was founded in 1974, and operates still today from Swakopmund Airport.

Media

Although Namibia's population is fairly small, the country has a diverse choice of media: Two TV stations, 19 radio stations (without counting community stations), 5 daily newspapers, several weeklies and special publications compete for the attention of the audience. Additionally, a mentionable amount of foreign media, especially South African, is available. Online media are mostly based on print publication contents. Namibia has a state-owned Press Agency, called NAMPA.[99]

History

The first newspaper in Namibia was the Windhoeker Anzeiger, founded 1898. Radio was introduced in 1969, TV in 1981. During German rule, the newspapers mainly reflected the living reality and the view of the white German-speaking minority. The black majority was ignored or depicted as a threat. During South African rule, the white bias continued, with mentionable influence of the Pretoria government on the "South West African" media system. Independent newspapers were seen as a menace to the existing order, critical journalists threatened.[99][100][101]

The daily newspapers include the private publications The Namibian, Die Republikein, Allgemeine Zeitung and Namibian Sun as well as the state-owned New Era. Except for the largest newspaper, The Namibian, which is owned by a trust, the other mentioned private newspapers are part of the Democratic Media Holdings.[99]

Other mentionable newspapers are the tabloid Informanté owned by TrustCo, the weekly Windhoek Observer, the weekly Namibia Economist, as well as the regional Namib Times. Current affairs magazines include Insight Namibia and the comparably new Prime Focus. Sister Namibia Magazine stands out as the longest running NGO magazine in Namibia, while Namibia Sport is the only national sport magazine. Furthermore, the print market is complemented with party publications, student newspapers and PR publications.[99]

Broadcasting

The broadcasting sector is dominated by the state-run Namibian Broadcasting Corporation (nbc). The public broadcaster offers a TV station as well as a "National Radio" in English and nine language services in locally spoken languages. The nine private radio stations in the country are mainly English-language channels, except for Radio Omulunga (Oshiwambo) and Kosmos 94.1 (Afrikaans). Privately held One Africa TV has competed with nbc since the 2000s.[99][102]

Media freedom

Compared to neighbouring countries, Namibia has a large degree of media freedom. Over the past years, the country usually ranked in the upper quarter of the Press Freedom Index of Reporters without Borders, reaching position 21 in 2010, being on par with Canada and the best-positioned African country.[103] The African Media Barometer shows similarly positive results.[citation needed] However, as in other countries, there is still mentionable influence of representatives of state and economy on media in Namibia.[99] In 2009, Namibia dropped to position 36 on the Press Freedom Index.[104] In 2013, it was 19th.[105]

Organisations

Media and journalists in Namibia are represented by the Namibian chapter of the Media Institute of Southern Africa and the Editors' Forum of Namibia. An independent media ombudsman was appointed in 2009 to prevent a state-controlled media council.[99]

See also

Lists

References

Footnotes

- ^ Smit, Nico (12 April 2012). "Namibia's population hits 2.1 million". The Namibian.

- ^ a b c d "Namibia". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ^ "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2010" (PDF). United Nations. 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Spriggs, A. 2001. "Namib desert". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- ^ Dierks, Klaus. "Biographies of Namibian Personalities, A". Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Dierks, Klaus. "Warmbad becomes two hundred years". Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ Vedder 1997, p. 177.

- ^ Vedder 1997, p. 659.

- ^ Joubert, Bruce. "An historical perspective on animal power use in South Africa" (PDF). Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa.

- ^ "German South West Africa". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ Drechsler, Horst (1980). The actual number of deaths in the limited number of battles with the Germany Schutztruppe (expeditionary force) were limited, most of the deaths occurred after fighting had ended due to the extermination order issued by the German military governor Lotha von Trotha. A substantial minority of Herero crossed the Kalahari desert into the British colony of Bechuanaland (modern-day Botswana) where a small community continues to live in western Botswana near to border with Namibia Let us die fighting, originally published (1966) under the title "Südwestafrika unter deutsche Kolonialherrschaft". Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

- ^ Adhikari, Mohamed (2008). "'Streams Of Blood And Streams Of Money': New Perspectives on the Annihilation of the Herero and Nama Peoples Of Namibia, 1904–1908". Kronos. 34: 303–320. JSTOR 41056613.

- ^ Madley, Benjamin (2005). "From Africa to Auschwitz: How German South West Africa Incubated Ideas and Methods Adopted and Developed by the Nazis in Eastern Europe". European History Quarterly. 35 (3): 429–464. doi:10.1177/0265691405054218. says it influenced Nazis.

- ^ Namibia's German Genocide. Dailymail.co.uk (2009-02-07). Retrieved on 2012-12-12.

- ^ Gerwarth, Robert; Malinowski, Stephan (2008). "L'Antichambre de l'Holocauste? A propos du Debat sur les Violences Coloniales et la Guerre d'Extermination Nazie". Vingtième Siècle. 99 (3): 143–159. doi:10.3917/ving.099.0143. JSTOR 20475396. says most scholars think it did not influence the Nazis.

- ^ Reinhart Kössler, and Henning Melber, "Völkermord und Gedenken: Der Genozid an den Herero und Nama in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1904–1908," ("Genocide and memory: the genocide of the Herero and Nama in German South-West Africa, 1904–08") Jahrbuch zur Geschichte und Wirkung des Holocaust 2004: 37–75

- ^ Henning Melber (January 2013). "Colonial shadows". D+C Development and Cooperation/ dandc.eu.

- ^ Petronella Sibeene (17 April 2009). "Swapo Party Turns 49". New Era.

- ^ Klaus Dierks Chronology of Namibian History, 1977

- ^ Tapscott, Chris (January 1994). "Land reform in Namibia: Why not?". Southern African Report. 9 (3): 12. Archived from the original on 24 December 2010.

- ^ "Chronology of Namibian Independence". Klausdierks.com. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ "Country report: Spotlight on Namibia". Commonwealth Secretariat. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- ^ a b "IRIN country profile Namibia". IRIN. Archived from the original on 17 February 2010. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- ^ http://www.eisa.org.za/WEP/nam5.htm Namibian President/Constitution

- ^ Shivute, Peter (2008). "Foreword". In Bösl, Anton; Horn, Nico (eds.). The Independence of the Judiciary in Namibia (PDF). Publications sponsored by Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. Macmillan Education Namibia. p. 10. ISBN 978-99916-0-807-5.

- ^ SWAPO:Dominant party?. Swapoparty.org. Retrieved on 2012-12-12.

- ^ Africa and the CON. Africanhistory.about.com. Retrieved on 2012-12-12.

- ^ Hopwood, Graham (February 2012). "Flying high". insight Namibia.

- ^ "Rank Order – Area". CIA World Fact Book. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- ^ Brandt, Edgar (21 September 2012). "Land degradation causes poverty". New Era.

- ^ Matundu-Tjiparuro, Mae (28 February 2011). "Khomas Region, a constitutional, political and geographical hybrid". Focus on: Khomas Region. supplement to New Era. p. 3.

- ^ "Composition of the Delimitation Commissions and the major decisions made from 1990 to present". Election Watch (1). Institute for Public Policy Research: 2. 2013.

- ^ "Namibia National Council". Inter-Parliamentary Union. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ "Landsat.usgs.gov". Landsat.usgs.gov. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ a b World Almanac. 2004.

- ^ Spriggs, A. 2001.(AT1315)

- ^ Spriggs, A. 2001.(AT1316)

- ^ Cowling, S. 2001.

- ^ Spriggs, A. 2001.(AT0709)

- ^ "NASA – Namibia's Coastal Desert". www.nasa.gov. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ^ "An Introduction to Namibia". www.geographia.com. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ^ "NACOMA – Namibian Coast Conservation and Management Project". www.nacoma.org.na. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ^ Sparks, Donald L. "Namibia's Coastal and Marine Development Potential". African Affairs. 83 (333): 477.

- ^ "Paper and digital Climate Section". Namibia Meteorological Services.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "The Rainy Season". Real Namibia. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ a b c "Namibia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ Olszewski, John (13 May 2009). "Climate change forces us to recognise new normals". Namibia Economist. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011.

- ^ Olszewski, John (25 June 2010). "Understanding Weather – not predicting it". Namibia Economist. Archived from the original on 7 December 2010.

- ^ Adams, Gerry (15 April 2011). "Debilitating floods hit northern and central Namibia". United Nations Radio.

- ^ van den Bosch, Servaas (29 March 2011). "Heaviest floods ever in Namibia". The Namibian.

- ^ "Namibia". The World Factbook (2025 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ Namibia from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- ^ a b "Background Note:Namibia". US Department of State. 26 October 2010.

- ^ "Bank of Namibia (BoN)". Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ The Namibian 4 February 2010 "Half of all Namibians unemployed" by Jo-Mare Duddy

- ^ Ndjebela, Toivo (18 November 2011). "Mwinga speaks out on his findings". New Era.

- ^ The Namibian 3 February 2010 "Tender Board tightens rules to protect jobs", by Tileni Mongudhi

- ^ "Tensions Simmer as Namibia Divides Its Farmland", The New York Times (2004-12-25).

- ^ "NAMIBIA: Key step in land reform completed", IRIN Africa

- ^ Lange, Glenn-marie (2004). "Wealth, Natural Capital, and Sustainable Development: Contrasting Examples from Botswana and Namibia". Environmental & Resource Economics. 29 (3): 257–83. doi:10.1007/s10640-004-4045-z.

- ^ McGrath, Matt. "Vast aquifer found in Namibia could last for centuries" BBC World Service (2012-07-20).

- ^ McGrath, Matt. "'Huge' water resource exists under Africa" BBC World Service (2012-04-20).

- ^ MacDonald A M, Bonsor H C, Dochartaigh B É Ó and Taylor R G (2012). "Quantitative maps of groundwater resources in Africa". Environ. Res. Lett. 7 (2): 024009. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/7/2/024009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mining in Namibia" (PDF). NIED. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ Oancea, Dan. Mining Uranium at Namibia's Langer Heinrich Mine

- ^ Oancea, Dan. Deep-Sea Mining and Exploration

- ^ The Diamond Investigation, chapter 1 by Edward Jay Epstein, in an interview with Harry Frederick Oppenheimer owner of De Beers.

- ^ Weidlich, Brigitte (7 January 2011). "Uranium: Saving or sinking Namibia?". The Namibian.

- ^ "A Framework/Model to Benchmark Tourism GDP in South Africa". Pan African Research & Investment Services. March 2010. p. 34.

- ^ Hartman, Adam (30 September 2009). "Tourism in good shape – Minister". The Namibian.

- ^ Humavindu, Michael N., Barnes, Jonothan I (October 2003). "Trophy Hunting in the Namibian Economy: An Assessment. Environmental Economics Unit, Directorate of Environmental Affairs, Ministry of Environment and Tourism, Namibia". South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 33 (2): 65–70.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Namibia top tourist destinations. Namibiatourism.com.na. Retrieved on 2012-12-12.

- ^ "Namibia, Windhoek Cost of Living".

- ^ PAYE12 Volume 18 published by The Ministry of Finance in Namibia

- ^ Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2009). "World Population Prospects, Table A.1" (PDF). 2008 revision. United Nations. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ China and Africa: Stronger Economic Ties Mean More Migration, By Malia Politzer, Migration Information Source, August 2008

- ^ a b c Central Intelligence Agency (2009). "Namibia". The World Factbook. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ Flight from Angola, The Economist (1975-08-16)

- ^ Lalita Prasad Singh (1980). The United Nations and Namibia. East African Publishing House.

- ^ "Census Summary Results". National Planning Commission of Namibia. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ Kapitako, Alvine (8 August 2011). "Namibia: 2011 Census Officially Launched". New Era. via allafrica.com.

- ^ "Methodology". National Planning Commission of Namibia. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ Duddy, Jo Maré (28 March 2013). "Census gives snapshot of Namibia's population". The Namibian.

- ^ "U.S. Department of State". State.gov. 10 June 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ Pütz, Martin. Official Monolingualism in Africa: A sociolinguistic assessment of linguistic and cultural pluralism in Africa. in: Discrimination through language in Africa? Perspectives on the Namibian Experience. Mouton de Gruyter. Berlin: 1995. p.155.

- ^ Sasman, Catherine (15 August 2011). "Portuguese to be introduced in schools". The Namibian. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ^ CIA World Factbook: Life Expectancy ranks

- ^ Hivinsight.com, HIV InSite Knowledge Base, Comprehensive, up-to-date information on HIV/AIDS treatment, prevention, and policy from the University of California San Francisco

- ^ "UNAIDS World AIDS Day Report 2011" (PDF). UNAIDS. Retrieved 2012-24-2.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Aidsinafrica.net.

- ^ Korenromp, E.L., Williams, B.G., de Vlas, S.J., Gouws, E., Gilks, C.F., Ghys, P.D., Nahlen, B.L. (2005). "Malaria Attributable to the HIV-1 Epidemic, Sub-Saharan Africa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (9): 1410–1419. doi:10.3201/eid1109.050337. PMC 3310631. PMID 16229771.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "WHO Country Offices in the WHO African Region" (PDF). Afro.who.int. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Nations Namibia- Education

- ^ "National Institute for Educational Development". Nied.edu.na. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ a b Stefanova, Kristina (August 2005). Protecting Namibia’s Natural Resources. usinfo.state.gov

- ^ Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) Programme Details (n.d.).

- ^ Nature in Local Hands: The Case for Namibia's Conservancies. UNEP, UNDP, WRI, and World Bank. 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rothe, Andreas (2010): Media System and News Selection in Namibia. p. 14-96

- ^ von Nahmen, Carsten (2001): Deutschsprachige Medien in Namibia

- ^ Links, Frederico (2006): We write what we like: The role of independent print media and independent reporting in Namibia

- ^ background. One Africa TV. Retrieved on 2012-12-12.

- ^ Press Freedom Index 2010 – Reporters Without Borders. En.rsf.org. Retrieved on 2012-12-12.

- ^ Press Freedom Index 2009 – Reporters Without Borders. En.rsf.org. Retrieved on 2012-12-12.

- ^ "Press Freedom Index 2013". Retrieved 24 June 2013.

Bibliography

- Cowling, S. 2001. "Succulent Karoo". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Spriggs, A. 2001. "Namibian Savannah Woodlands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Spriggs, A. 2001. "Kalahari Acacia-Baikiaea Woodland". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Vedder, Heinrich (1997). Das alte Südwestafrika. Südwestafrikas Geschichte bis zum Tode Mahareros 1890 (in German) (7th ed.). Windhoek: Namibia Scientific Society. ISBN 0-949995-33-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

General references

- Christy, S.A. (2007) Namibian Travel Photography

- Horn, N/Bösl, A (eds), Human rights and the rule of law in Namibia, Macmillan Namibia 2008.

- Horn, N/Bösl, A (eds), The independence of the judiciary in Namibia, Macmillan Namibia 2008.

- KAS Factbook Namibia, Facts and figures about the status and development of Namibia, Ed. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V.

- Fritz, Jean-Claude . La Namibie indépendante. Les coûts d'une décolonisation retardée, Paris, L'Harmattan, 1991.

- World Almanac. 2004. World Almanac Books. New York, NY

External links

Namibia travel guide from Wikivoyage

Namibia travel guide from Wikivoyage

- "Namibia". The World Factbook (2025 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Namibia from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Template:Dmoz

Wikimedia Atlas of Namibia

Wikimedia Atlas of Namibia- Key Development Forecasts for Namibia from International Futures

- Government

- Republic of Namibia Government Portal

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- Education

- National Parks

- Use dmy dates from June 2011

- Namibia

- Countries in Africa

- Member states of the African Union

- Countries bordering the Atlantic Ocean

- English-speaking countries and territories

- German-speaking countries and territories

- Afrikaans-speaking countries and territories

- Liberal democracies

- Member states of the Commonwealth of Nations

- Republics

- States and territories established in 1990

- Member states of the United Nations

- Bantu countries and territories

- Commonwealth republics

- Former German colonies