Federal Reserve Act: Difference between revisions

disambiguated |

→Subsequent Amendments: changed "throws" to the correct contextual spelling of throes. |

||

| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

==Subsequent Amendments== |

==Subsequent Amendments== |

||

The act originally granted a charter for twenty years, to be renewed in 1933. Fortunately for the Federal Reserve System, this clause was amended on February 25, 1927 to extend the act, "To have succession after the approval of this Act until dissolved by Act of Congress or until forfeiture of franchise for violation of law."<ref name=FederalReserveActExtension>''[http://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/section4.htm Section 4, Subsection 4, Second paragraph ]'' of the Federal Reserve Act, Last update: August 2, 2013, Accessed: August, 22, 2013</ref> ({{Usctc|12|3}}. As amended by act of Feb. 25, 1927 ({{USStat|44|1234}})). By 1933 the US was in the |

The act originally granted a charter for twenty years, to be renewed in 1933. Fortunately for the Federal Reserve System, this clause was amended on February 25, 1927 to extend the act, "To have succession after the approval of this Act until dissolved by Act of Congress or until forfeiture of franchise for violation of law."<ref name=FederalReserveActExtension>''[http://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/section4.htm Section 4, Subsection 4, Second paragraph ]'' of the Federal Reserve Act, Last update: August 2, 2013, Accessed: August, 22, 2013</ref> ({{Usctc|12|3}}. As amended by act of Feb. 25, 1927 ({{USStat|44|1234}})). By 1933 the US was in the throes of the [[Great Depression]] and public sentiment with regards to the Federal Reserve System and the banking community in general had significantly deteriorated. Given the political context, including the presidency of [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]] and the [[New Deal]], it is uncertain whether the Federal Reserve System would have survived in it's current form. |

||

In the 1930s the Federal Reserve Act was amended to create the [[Federal Open Market Committee]] (FOMC), consisting of the seven members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and five representatives from the Federal reserve banks (Section 12B). The FOMC is required to meet at least four times a year (the practice is usually eight times) and is empowered to direct all open-market operations of the Federal reserve banks. |

In the 1930s the Federal Reserve Act was amended to create the [[Federal Open Market Committee]] (FOMC), consisting of the seven members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and five representatives from the Federal reserve banks (Section 12B). The FOMC is required to meet at least four times a year (the practice is usually eight times) and is empowered to direct all open-market operations of the Federal reserve banks. |

||

Revision as of 23:32, 27 August 2013

| |

| Long title | An Act to provide for the establishment of Federal reserve banks, to furnish an elastic currency, to afford means of rediscounting commercial paper, to establish a more effective supervision of banking in the United States, and for other purposes. |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 63rd United States Congress |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub. L. 63–43 |

| Statutes at Large | ch. 6, 38 Stat. 251 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

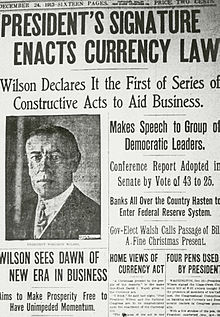

The Federal Reserve Act (ch. 6, 38 Stat. 251, enacted December 23, 1913, 12 U.S.C. ch. 3) is an Act of Congress that created and set up the Federal Reserve System, the central banking system of the United States of America, and granted it the legal authority to issue Federal Reserve Notes (now commonly known as the U.S. Dollar) and Federal Reserve Bank Notes as legal tender. The Act was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson.

Background

For nearly eighty years, the U.S. was without a central bank after the charter for the Second Bank of the United States was allowed to expire. After various financial panics, particularly a severe one in 1907, some Americans became persuaded that the country needed some sort of banking and currency reform that would,[1] when threatened by financial panics, provide a ready reserve of liquid assets, and furthermore allow for currency and credit to expand and contract seasonally within the U.S. economy.

Some of this was chronicled in the reports of the National Monetary Commission (1909–1912), which was created by the Aldrich–Vreeland Act in 1908. Included in a report of the Commission, submitted to Congress on January 9, 1912, were recommendations and draft legislation with 59 sections, for proposed changes in U.S. banking and currency laws.[2] The proposed legislation was known as the Aldrich Plan, named after the chairman of the Commission, Republican Senator Nelson W. Aldrich of Rhode Island.

The Plan called for the establishment of a National Reserve Association with 15 regional district branches and 46 geographically dispersed directors primarily from the banking profession. The Reserve Association would make emergency loans to member banks, print money, and act as the fiscal agent for the U.S. government. State and nationally chartered banks would have the option of subscribing to specified stock in their local association branch.[2] It is generally believed that the outline of the Plan had been formulated in a secret meeting on Jekyll Island in November 1910, which Aldrich and other well connected financiers attended.[3]

Since the Aldrich Plan essentially gave full control of this system to private bankers, there was strong opposition to it from rural and western states because of fears that it would become a tool of certain rich and powerful financiers in New York City, referred to as the "Money Trust".[4] Indeed, from May 1912 through January 1913 the Pujo Committee, a subcommittee of the House Committee on Banking and Currency, held investigative hearings on the alleged Money Trust and its interlocking directorates. These hearings were chaired by Rep. Arsene Pujo, a Democratic representative from Louisiana.[5]

In the election of 1912, the Democratic Party won control of the White House and both chambers of Congress. The party's platform stated strong opposition "to the so called Aldrich bill for the establishment of a central bank." However, the platform also called for a systematic revision of banking laws in ways that would provide relief from financial panics, unemployment and business depression, and would protect the public from the "domination by what is known as the Money Trust."[6]

Legislative history

The banking and currency reform plan advocated by President Wilson in 1913 was sponsored by the chairmen of the House and Senate Banking and Currency committees, Representative Carter Glass, a Democrat of Virginia and Senator Robert Latham Owen, a Democrat of Oklahoma. According to the House committee report accompanying the Currency bill (H.R. 7837) or the Glass-Owen bill, as it was often called during the time, the legislation was drafted from ideas taken from various proposals, including the Aldrich bill.[6] However, unlike the Aldrich plan, which gave controlling interest to private bankers with only a small public presence, the new plan gave an important role to a public entity, the Federal Reserve Board, while establishing a substantial measure of autonomy for the (regional) Reserve Banks which, at that time, were allowed to set their own discount rates. Also, instead of the proposed currency being an obligation of the private banks, the new Federal Reserve note was to be an obligation of the U.S. Treasury. In addition, unlike the Aldrich plan, membership by nationally chartered banks was mandatory, not optional. The changes were significant enough that the earlier opposition to the proposed reserve system from Progressive Democrats was largely appeased; instead, opposition to the bill came largely from the more business-friendly Republicans instead of from the Democrats.[1]

After months of hearings, debates, votes and amendments, the proposed legislation, with 30 sections, was enacted as the Federal Reserve Act. The House, on December 22, 1913,[7] agreed to the conference report on the Federal Reserve Act bill by a vote of 298 yeas to 60 nays, with 76 not voting. The Senate, on December 23, 1913, agreed to it by a vote of 43 yeas to 25 nays with 27 not voting. The record shows that there were no Democrats voting "nay" in the Senate and only two in the House. The record also shows that almost all of those not voting for the bill had previously declared their intentions and were paired with members of opposite intentions.[8]

The Act

The plan adopted in the original Federal Reserve Act called for the creation of a System that contained both private and public entities. There were to be at least eight, and no more than 12, private regional Federal reserve banks (12 were established) each with its own branches, board of directors and district boundaries[9] and the System was to be headed by a seven member Federal Reserve Board made up of public officials appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate (strengthened and renamed in 1935 as the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System with the Secretary of the Treasury and the Comptroller of the Currency dropped from the Board).[10] Also created as part of the Federal Reserve System was a 12 member Federal Advisory Committee[11] and a single new United States currency, the Federal Reserve Note.[12]

In the Federal Reserve Act, Congress provided that all nationally chartered banks were required to become members of the Federal Reserve System. The Act required these banks to purchase specified non-transferable stock in their regional Federal reserve banks, and to set aside a stipulated amount of non-interest bearing reserves with their respective reserve banks. Since 1980, all depository institutions have been required to set aside reserves with the Federal Reserve. Such institutions are entitled to certain Federal Reserve services.[13] State chartered banks were given the option of becoming members of the Federal Reserve System and in the case of the exercise of such option were to be subject to supervision, in part, by the Federal Reserve System.[14] Member banks became entitled to have access to discounted loans at the discount window in their respective reserve banks, to a 6% annual dividend in their Federal Reserve stock, and to other services.[15]

Section 15 of the Act also permitted Federal Reserve banks to act as fiscal agents for the United States government.[16]

Section 25 allowed banks to establish foreign branches. Citibank became the first to do so with a branch in Buenos Aires.[17]

Subsequent Amendments

The act originally granted a charter for twenty years, to be renewed in 1933. Fortunately for the Federal Reserve System, this clause was amended on February 25, 1927 to extend the act, "To have succession after the approval of this Act until dissolved by Act of Congress or until forfeiture of franchise for violation of law."[18] (12 U.S.C. ch. 3. As amended by act of Feb. 25, 1927 (44 Stat. 1234)). By 1933 the US was in the throes of the Great Depression and public sentiment with regards to the Federal Reserve System and the banking community in general had significantly deteriorated. Given the political context, including the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, it is uncertain whether the Federal Reserve System would have survived in it's current form.

In the 1930s the Federal Reserve Act was amended to create the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), consisting of the seven members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and five representatives from the Federal reserve banks (Section 12B). The FOMC is required to meet at least four times a year (the practice is usually eight times) and is empowered to direct all open-market operations of the Federal reserve banks.

During the 1970s, the Federal Reserve Act was amended to require the Board and the FOMC "to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates."[19] Also in that decade, the Act was amended so that the member governor proposed by the President to be Chairman would have a four-year term as Chairman and would be subject to confirmation by the Senate (member governors per se each have 14 year terms, with a specific term ending every two years) (Section 10). The Chairman was also required to appear before Congress at semi-annual hearings to report on the conduct of monetary policy, on economic development, and on the prospects for the future.[20]

The Federal Reserve Act has been amended by some 200 subsequent laws of Congress.[21] It continues to be one of the principal banking laws of the United States.

Criticism

Controversy about the Federal Reserve Act and the establishment of the Federal Reserve System has existed since prior to its passage. Some of the questions raised include: whether Congress has the Constitutional power to delegate its power to coin money or issue paper money, whether the Federal Reserve is a public cartel of private banks (also called a banking cartel) established to protect powerful financial interests, and whether the Federal Reserve's actions increased the severity of the Great Depression in the 1930s (and/or the severity or frequency of other boom-bust economic cycles, such as the late-2000s recession).

See also

References

- ^ a b Historical Beginnings... The Federal Reserve by Roger T. Johnson, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 1999

- ^ a b Report of the National Monetary Commission. January 9, 1912, letter from the Secretary of the Commission and a draft bill to incorporate the National Reserve Association of the United States, and for other purposes. Sen. Doc. No. 243. 62d Congress. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1912.

- ^ Paul Warburg's Crusade to Establish a Central Bank in the United States Michael A. Whitehouse, 1989. In attendance at the meeting were Aldrich; Paul Warburg; Frank Vanderlip, president of National City Bank; Henry P. Davison, a J.P. Morgan partner; Benjamin Strong, vice president of Banker's Trust Co.; and A. Piatt Andrew, former secretary of the National Monetary Commission and then assistant secretary of the Treasury.

- ^ Wicker, Elmus (2005). "The Great Debate on Banking Reform: Nelson Aldrich and the Origins of the Fed" (Document). Ohio University PressTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|isbn=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). See also book review. - ^ Money Trust Investigation - Investigations of Financial and Monetary Conditions in the United States under House Resolutions Nos. 429 and 504 before a subcommittee of the House Committee on Banking and Currency. 27 Parts. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1913.

- ^ a b Changes in the Banking and Currency System of the United States. House Report No. 69, 63d Congress to accompany H.R. 7837, submitted to the full House by Mr. Glass, from the House Committee on Banking and Currency, September 9, 1913. A discussion of the deficiencies of the then current banking system as well as those in the Aldrich Plan and quotations from the 1912 Democratic platform are laid out in this report, pages 3-11.

- ^ Congressional Record December 23 1913

- ^ Voting record on the conference report of the Federal Reserve Act. Vol. 51 Congressional Record, pages 1464 and 1487-1488, December 22 and 23, 1913.

- ^ Sections 2, 3, and 4 of the Act.

- ^ Section 10 of the Act.

- ^ Section 12 of the Act.

- ^ Section 16 of the Act.

- ^ Sections 2 and 19 of the Act

- ^ Section 9 of the Act.

- ^ Sections 13 and 7 of the Act.

- ^ McKinney, Richard J., "The Federal Reserve System: Information Sources at the Nation's Central Bank," Vol. 22, Legal Reference Services Quarterly, pp. 29-44 (2003). This publication briefly explains the historical development of the sections of the Federal Reserve Act and other banking laws and regulations.

- ^ "Extending our Foreign Commerce". The Independent. Jul 13, 1914. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Section 4, Subsection 4, Second paragraph of the Federal Reserve Act, Last update: August 2, 2013, Accessed: August, 22, 2013

- ^ Section 2A of the Act

- ^ Section 2B of the Act.

- ^ Textual Changes in the Federal Reserve Act and Related Laws, Table IV. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

External links

- Text of the current Federal Reserve Act, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

- Text of Federal Reserve Act as laid out in the U.S. Code, Cornell Law School.

- Text of the original Federal Reserve Act, U.S. Congress, 1913.

- Federal Reserve Act, signed by Woodrow Wilson

- Historical Beginnings... The Federal Reserve by Roger T. Johnson, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 1999.

- Paul Warburg's Crusade to Establish a Central Bank in the United States by Michael A. Whitehouse, 1989.

- The Federal Reserve System In Brief - An online publication from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

- The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 - A Legislative History, Law Librarians' Society of Washington, DC, Inc., 2009

- Historical documents related to the Federal Reserve Act and subsequent amendments