Mamallapuram: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| Line 120: | Line 120: | ||

File:Stone Carvings at Mahabalipuram.JPG|Stone Carvings at Mahabalipuram |

File:Stone Carvings at Mahabalipuram.JPG|Stone Carvings at Mahabalipuram |

||

File:SeaShore Temple.jpg|silhouette of mahabalipuram seashore temple |

File:SeaShore Temple.jpg|silhouette of mahabalipuram seashore temple |

||

File:Recumbent vischnu.JPG|Mahabalipuram seashore temple - Recumbent Vischnu |

|||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

Revision as of 23:28, 8 November 2013

Mahabalipuram

Mamalllapuram | |

|---|---|

town | |

View of Shore Temple, Mahabalipuram / Mamallapuram | |

| Country | India |

| State | Tamil Nadu |

| District | Kancheepuram |

| Elevation | 12 m (39 ft) |

| Population (2001) | |

• Total | 12,049 |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Tamil |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 603104 |

| Telephone code | 91-44 |

Mahabalipuram, also known as Mamallapuram (Template:Lang-ta) is a town in Kancheepuram district in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is around 60 km south from the city of Chennai. It is an ancient historic town and was a bustling seaport during the time of Periplus (1st century CE) and Ptolemy (140 CE). Ancient Indian traders who went to countries of South East Asia sailed from the seaport of Mahabalipuram.

By the 7th Century it was a Port city of South Indian dynasty of the Pallavas. It has a group of sanctuaries, which was carved out of rock along the Coromandel coast in the 7th and 8th centuries : rathas (temples in the form of chariots), mandapas (cave sanctuaries), giant open-air reliefs such as the famous 'Descent of the Ganges', and the temple of Rivage, with thousands of sculptures to the glory of Shiva. All the group has been classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

It has an average elevation of 12 metres (39 feet). The modern city of Mahabalipuram was established by the British Raj in 1827.[1]

History

Megalithic burial urns, cairn circles and jars with burials dating to the very dawn of the Christian era have been discovered near Mamallapuram. The Sangam age poem Perumpāṇāṟṟuppaṭai relates the rule of King Thondaiman Ilam Thiraiyar at Kanchipuram of the Tondai Nadu port Nirppeyyaru which scholars identify with the present-day Mamallapuram. Chinese coins and Roman coins of Theodosius I in the 4th century CE have been found at Mamallapuram revealing the port as an active hub of global trade in the late classical period. Two Pallava coins bearing legends read as Srihari and Srinidhi have been found at Mamallapuram. The Pallava kings ruled Mamallapuram from Kanchipuram; the capital of the Pallava dynasty from the 3rd century to 9th century CE, and used the port to launch trade and diplomatic missions to Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia.

An 8th-century Tamil text written by Thirumangai Alvar described this place as Sea Mountain ‘where the ships rode at anchor bent to the point of breaking laden as they were with wealth, big trunked elephants and gems of nine varieties in heaps’. It is also known by several other names such as Mamallapattana and Mamallapuram. Another name by which Mahabalipuram has been known to mariners, at least since Marco Polo’s time is "Seven Pagodas" alluding to the Seven Pagodas of Mahabalipuram that stood on the shore, of which one, the Shore Temple, survives.[2]

The temples of Mamallapuram, portraying events described in the Mahabharata, were built largely during the reigns of Narasimhavarman and his successor Rajasimhavarman and showcase the movement from rock-cut architecture to structural building. The city of Mahabalipuram was largely developed by the Pallava king Narasimhavarman I in the 7th century AD.[2] The mandapa or pavilions and the rathas or shrines shaped as temple chariots are hewn from the granite rock face, while the famed Shore Temple, erected half a century later, is built from dressed stone. What makes Mamallapuram so culturally resonant are the influences it absorbs and disseminates. The Shore Temple includes many bas reliefs, including one 100 ft. long and 45 ft. high, carved out of granite.[3]

All but one of the rathas from the first phase of Pallava architecture are modeled on the Buddhist viharas or monasteries and chaitya halls with several cells arranged around a courtyard.[4] Art historian Percy Brown, in fact, traces the possible roots of the Pallava Mandapa to the similar rock-cut caves of Ajanta Caves and Ellora Caves. Referring to Narasimhavarman's victory in AD 642 over the Chalukyan king Pulakesin II, Brown says the Pallava king may have brought the sculptors and artisans back to Kanchi and Mamallapuram as 'spoils of war'.[5]

The fact that different shrines were dedicated to different deities is evidence of an increased sectarianism at the time of their construction. A bas-relief on a sculpted cliff has an image of Shiva and a shrine dedicated to Vishnu, indicating the growing importance of these Sangam period deities and a weakening of the roles of Vedic gods such as Indra and Soma.[6]

Landmarks

The monuments are mostly rock-cut and monolithic, and constitute the early stages of Dravidian architecture wherein Buddhist elements of design are prominently visible. They are constituted by cave temples, monolithic rathas (chariots), sculpted reliefs and structural temples. The pillars are of the Dravidian order. The sculptures are excellent examples of Pallava art. They are located in the side of the cliffs near India's Bay of Bengal.

It is believed by some that this area served as a school for young sculptors. The different sculptures, some half finished, may have been examples of different styles of architecture, probably demonstrated by instructors and practiced on by young students. This can be seen in the Pancha Rathas where each Ratha is sculpted in a different style. These five Rathas were all carved out of a single piece of granite in situ.[3] While excavating Khajuraho, Alex Evans, a stonemason and sculptor, recreated a stone sculpture made out of sandstone, which is softer than granite, under 4 feet that took about 60 days to carve. The carving at Mahabalipuram must have required hundreds of highly skilled sculptors.[7]

Some important structures include:

- Thirukadalmallai, the temple dedicated to Lord Vishnu. It was also built by Pallava King in order to safeguard the sculptures from the ocean. It is told that after building this temple, the remaining architecture was preserved and was not corroded by sea.

- Descent of the Ganges or Arjuna's Penance – a giant open-air bas relief

- Varaha Cave Temple – a small rock-cut temple dating back to the 7th century.

- The Shore Temple – a structural temple along the Bay of Bengal with the entrance from the western side away from the sea. Recent excavations have revealed new structures here.

- Pancha Rathas (Five Chariots) – five monolithic pyramidal structures named after the Pandavas (Arjuna, Bhima, Yudhishtra, Nakula and Sahadeva) and Draupadi. An interesting aspect of the rathas is that, despite their sizes they are not assembled – each of these is carved from one single large piece of stone.

- Light House, built in 1894.

Demography

As of 2001[update] India census,[8] Mahabalipuram had a population of 12,345.[9] Males constitute 52% of the population and females 48%. Mahabalipuram has an average literacy rate of 74%, higher than the national average of 59.5%: male literacy is 82%, and female literacy is 66%. In Mahabalipuram, 12% of the population is under 6 years of age.

Gallery

-

Shore temple, view from the north face

-

Sunrise at Shore Temple

-

Panoramic view of sculptures

-

Five Rathas in Mahabalipuram diagonal view

-

Mahabalipuram Shore Temples

-

Shore Temple Mahabalipuram

-

Elephant and other creatures carved in granite at Mahabalipuram.

-

Cave Temple at Mahabalipuram.

-

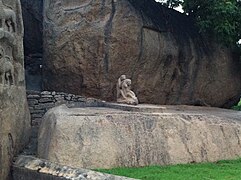

Monkey picking lice off other monkey at Mahabalipuram.

-

Pancha Rathas at Mamallapuram

-

Light House

-

Shore Temple in Mahabalipuram

-

Tiger Cave

-

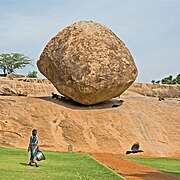

Krishna's Butter Ball

-

Submerged Temple at Mahabalipuram

-

Mamallapuram Beach

-

Arjuna's Penance

-

Mahabalipuram Temple at Dusk

-

Stone Carvings at Mahabalipuram

-

silhouette of mahabalipuram seashore temple

-

Mahabalipuram seashore temple - Recumbent Vischnu

See also

Notes

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Edition (1982), Vol. VI, p. 497

- ^ a b "Underwater investigations off Mahabalipuram" (PDF). Current Science. 86 (9). 10 May 2004.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Ancient Discoveries: Lost Cities of the Deep History Channel

- ^ "Mahabalipuram Tamilnadu". Tamilnadu.com. 29 September 2012.

- ^ http://www.pilgrimage-india.com/south-india-pilgrimage/mahabalipuram.html

- ^ Doniger, Wendy, The Hindus: An Alternative History, Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-959334-7 (pbk)

- ^ "Lost Worlds of the Kama Sutra" History channel

- ^ Template:GR

- ^ "Census of towns in Tamil Nadu" (PDF). Census of India. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

References

- Ayyar, P. V. Jagadisa (1991), South Indian shrines: illustrated, New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, ISBN 81-206-0151-3.

- Bradnock, Roma (2009), Footprint India, USA: Patrick Dawson, ISBN 1-904777-00-7

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help). - Frommer's India. Frommer's. 2010. p. 350. ISBN 0-470-55610-2, ISBN 978-0-470-55610-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Hurd, James (2010), Temples of Tamilnad, USA: Xilbris Corporation, ISBN 978-1-4134-3843-7

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help). - Singh, Sarina (2009), South India (Lonely Planet Regional Guide) (5th edition ed.), Lonely Planet, ISBN 978-1-74179-155-6

{{citation}}:|edition=has extra text (help)