Aaron Swartz: Difference between revisions

Petrarchan47 (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

===Activism=== |

===Activism=== |

||

In 2008, Swartz founded Watchdog.net, "the good government site with teeth," to aggregate and visualize data about politicians.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/sj/2011/07/24/aaron-swartz-v-united-states/ |title=Aaron Swartz vs. United States |first=Sam |last=Klein |date=July 24, 2011 |work=The Longest Now |publisher=Weblogs at Harvard Law School |quote=He founded watchdog.net [act.watchdog.net, © 2012 Demand Progress] to aggregate ... data about politicians – including where their money comes from. }}</ref> In the same year, he wrote a widely circulated ''Open Access Guerilla Manifesto''.<ref name="Quinn">{{cite news |last=Norton |first=Quinn |title=Life inside the Aaron Swartz investigation |newspaper=The Atlantic |location=D.C. |date=March 3, 2013 |url=http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/03/life-inside-the-aaron-swartz-investigation/273654/ |accessdate=2013-03-08 }}</ref><ref name="Guard"/><ref name=OAGM/><ref name=TechRev>{{cite news |title=‘Guerilla activist' releases 18,000 scientific papers |first=Samantha |last=Murphy |url=http://www.technologyreview.com/news/424780/guerilla-activist-releases-18000-scientific-papers/ |newspaper=MIT Technology Review |date=July 22, 2011 |quote=In a 2008 ‘Guerilla Open Access Manifesto,' Swartz called for activists to ‘fight back' against services that held academic papers hostage behind paywalls.}}</ref> |

In 2008, Swartz founded Watchdog.net, "the good government site with teeth," to aggregate and visualize data about politicians.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/sj/2011/07/24/aaron-swartz-v-united-states/ |title=Aaron Swartz vs. United States |first=Sam |last=Klein |date=July 24, 2011 |work=The Longest Now |publisher=Weblogs at Harvard Law School |quote=He founded watchdog.net [act.watchdog.net, © 2012 Demand Progress] to aggregate ... data about politicians – including where their money comes from. }}</ref>. The site no longer exists. In the same year, he wrote a widely circulated ''Open Access Guerilla Manifesto''.<ref name="Quinn">{{cite news |last=Norton |first=Quinn |title=Life inside the Aaron Swartz investigation |newspaper=The Atlantic |location=D.C. |date=March 3, 2013 |url=http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/03/life-inside-the-aaron-swartz-investigation/273654/ |accessdate=2013-03-08 }}</ref><ref name="Guard"/><ref name=OAGM/><ref name=TechRev>{{cite news |title=‘Guerilla activist' releases 18,000 scientific papers |first=Samantha |last=Murphy |url=http://www.technologyreview.com/news/424780/guerilla-activist-releases-18000-scientific-papers/ |newspaper=MIT Technology Review |date=July 22, 2011 |quote=In a 2008 ‘Guerilla Open Access Manifesto,' Swartz called for activists to ‘fight back' against services that held academic papers hostage behind paywalls.}}</ref> |

||

In 2009, wanting to learn about effective activism, Swartz helped launch the [[Progressive Change Campaign Committee]].<ref>[http://boldprogressives.org/2013/01/progressive-change-campaign-committee-statement-on-the-passing-of-aaron-swartz/ Progressive Change Campaign Committee Statement on the Passing of Aaron Swartz]</ref> He wrote on his blog, "I spend my days experimenting with new ways to get progressive policies enacted and progressive politicians elected."<ref>[http://www.aaronsw.com/weblog/pcccjob How to Get a Job Like Mine (Aaron Swartz's Raw Thought)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> Swartz led the first activism event of his career with the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, delivering thousands of "Honor Kennedy" petition signatures to Massachusetts legislators asking them to fulfill former Senator [[Ted Kennedy]]'s last wish by appointing a senator to vote for health care reform.<ref>[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KhSp2zp9GtY Victory! HonorKennedy.com - YouTube<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

In 2009, wanting to learn about effective activism, Swartz helped launch the [[Progressive Change Campaign Committee]].<ref>[http://boldprogressives.org/2013/01/progressive-change-campaign-committee-statement-on-the-passing-of-aaron-swartz/ Progressive Change Campaign Committee Statement on the Passing of Aaron Swartz]</ref> He wrote on his blog, "I spend my days experimenting with new ways to get progressive policies enacted and progressive politicians elected."<ref>[http://www.aaronsw.com/weblog/pcccjob How to Get a Job Like Mine (Aaron Swartz's Raw Thought)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> Swartz led the first activism event of his career with the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, delivering thousands of "Honor Kennedy" petition signatures to Massachusetts legislators asking them to fulfill former Senator [[Ted Kennedy]]'s last wish by appointing a senator to vote for health care reform.<ref>[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KhSp2zp9GtY Victory! HonorKennedy.com - YouTube<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:22, 23 January 2014

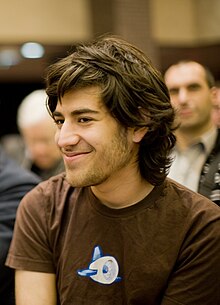

Aaron Swartz | |

|---|---|

Aaron Swartz at a Creative Commons event on December 13, 2008 | |

| Born | Aaron H. Swartz[1] November 8, 1986 |

| Died | January 11, 2013 (aged 26) Crown Heights, Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Suicide by hanging |

| Occupation(s) | Software developer, writer, Internet activist |

| Title | Fellow, Harvard University Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics |

| Awards | American Library Association's James Madison Award (posthumously) EFF Pioneer Award 2013 (posthumously) |

| Website | aaronsw.com rememberaaronsw.com |

Aaron Hillel Swartz (November 8, 1986 – January 11, 2013) was an American computer programmer, writer, political organizer and Internet activist. Swartz was involved in the development of the web feed format RSS,[3] the organization Creative Commons,[4] the website framework web.py[5] and the social news site, Reddit, in which he became a partner after its merger with his company, Infogami.[i]

Swartz's later work focused on sociology, civic awareness and activism.[6][7] He helped launch the Progressive Change Campaign Committee in 2009 to learn more about effective online activism. In 2010 he became a research fellow at Harvard University's Safra Research Lab on Institutional Corruption, directed by Lawrence Lessig.[8][9] He founded the online group Demand Progress, known for its campaign against the Stop Online Piracy Act.

On January 6, 2011, Swartz was arrested by MIT police on state breaking-and-entering charges, after systematically downloading academic journal articles from JSTOR.[10][11] Federal prosecutors later charged him with two counts of wire fraud and 11 violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act,[12] carrying a cumulative maximum penalty of $1 million in fines, 35 years in prison, asset forfeiture, restitution and supervised release.[13]

Two years later, two days after the prosecution denied his lawyer's second offer of a plea bargain, Swartz was found dead in his Brooklyn, New York apartment, where he had hanged himself.[14][15]

In June 2013, Swartz was posthumously inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame.[16][17]

Life and works

Swartz was born in Chicago, Illinois, the eldest son of Susan and Robert Swartz.[1][18] His father had founded the software firm Mark Williams Company. Swartz immersed himself in the study of computers, programming, the Internet, and Internet culture.[19] He attended North Shore Country Day School, a small private school near Chicago, until 9th grade.[20] Swartz left high school in the 10th grade, and enrolled in courses at a Chicago area college.[21][22]

At age 13, Swartz won an ArsDigita Prize, given to young people who create "useful, educational, and collaborative" noncommercial websites.[1][23] At age 14, he became a member of the working group that authored the RSS 1.0 web syndication specification.[24]

W3C

In 2001, Swartz joined the RDFCore working group at the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C),[25] where he authored RFC 3870, Application/RDF+XML Media Type Registration. The document described a new media type, "RDF/XML", designed to support the Semantic Web.[26]

Markdown

Swartz was co-creator, with John Gruber, of Markdown,[27][28] a simplified markup standard derived from HTML, and author of its html2text translator. Markdown remains in widespread use.

Infogami, Reddit, Jottit

Swartz attended Stanford University. After the summer of his freshman year, he attended Y Combinator's first Summer Founders Program where he started the software company Infogami. Infogami's wiki platform was used to support the Internet Archive's Open Library project and the web.py web framework that Swartz had created,[29] but he felt he needed co-founders to proceed further. Y-Combinator organizers suggested that Infogami merge with Reddit,[30][31] which it did in November 2005.[30][32] Reddit at first found it difficult to make money from the project, but the site later gained in popularity, with millions of users visiting it each month.

In October 2006, Reddit was acquired by Condé Nast Publications, the owner of Wired magazine.[19][33] Swartz moved with his company to San Francisco to work on Wired.[19] Swartz found office life uncongenial, and he ultimately left the company.[34]

In September 2007, Swartz joined with Simon Carstensen to launch Jottit.

Activism

In 2008, Swartz founded Watchdog.net, "the good government site with teeth," to aggregate and visualize data about politicians.[35]. The site no longer exists. In the same year, he wrote a widely circulated Open Access Guerilla Manifesto.[36][37][38][39]

In 2009, wanting to learn about effective activism, Swartz helped launch the Progressive Change Campaign Committee.[40] He wrote on his blog, "I spend my days experimenting with new ways to get progressive policies enacted and progressive politicians elected."[41] Swartz led the first activism event of his career with the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, delivering thousands of "Honor Kennedy" petition signatures to Massachusetts legislators asking them to fulfill former Senator Ted Kennedy's last wish by appointing a senator to vote for health care reform.[42]

In 2010,[43] Swartz co-founded Demand Progress,[44] a political advocacy group that organizes people online to "take action by contacting Congress and other leaders, funding pressure tactics, and spreading the word" about civil liberties, government reform, and other issues.[45]

During academic year 2010–11, Swartz conducted research studies on political corruption as a Lab Fellow in Harvard University's Edmond J. Safra Research Lab on Institutional Corruption.[8][9]

Author Cory Doctorow, in his novel, Homeland, "dr[ew] on advice from Swartz in setting out how his protagonist could use the information now available about voters to create a grass-roots anti-establishment political campaign."[46] In an afterword to the novel, Swartz wrote, "these [political hacktivist] tools can be used by anyone motivated and talented enough.... Now it's up to you to change the system.... Let me know if I can help."[46]

Stop Online Piracy Act

Swartz was instrumental in the campaign to prevent passage of the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), which sought to combat Internet copyright violations but was criticized on the basis that it would have made it easier for the U.S. government to shut down web sites accused of violating copyright and would have placed intolerable burdens on Internet providers.[47] Following the defeat of the bill, Swartz was the keynote speaker at the F2C:Freedom to Connect 2012 event in Washington, D.C., on May 21, 2012. His speech was titled "How We Stopped SOPA" and he informed the audience:

This bill ... shut down whole websites. Essentially, it stopped Americans from communicating entirely with certain groups....

I called all my friends, and we stayed up all night setting up a website for this new group, Demand Progress, with an online petition opposing this noxious bill.... We [got] ... 300,000 signers.... We met with the staff of members of Congress and pleaded with them.... And then it passed unanimously....

And then, suddenly, the process stopped. Senator Ron Wyden ... put a hold on the bill.[48][49]

He added, "We won this fight because everyone made themselves the hero of their own story. Everyone took it as their job to save this crucial freedom."[48][49] He was referring to a series of protests against the bill by numerous websites that was described by the Electronic Frontier Foundation as the biggest in Internet history, with over 115,000 sites altering their webpages.[50] Swartz also presented on this topic at an event organized by ThoughtWorks.[51]

Wikipedia

Swartz volunteered as an editor at Wikipedia, and in 2006, he ran unsuccessfully for the Wikimedia Foundation's Board of Directors. Also in 2006, Swartz wrote an analysis of how Wikipedia articles are written, and concluded that the bulk of the actual content comes from tens of thousands of occasional contributors, or "outsiders", each of whom may not make many other contributions to the site, while a core group of 500 to 1,000 regular editors tend to correct spelling and other formatting errors.[52] According to Swartz: "the formatters aid the contributors, not the other way around."[52][53]

His conclusions, based on the analysis of edit histories of several randomly selected articles, contradicted the opinion of Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales, who believed the core group of regular editors were providing most of the content while thousands of others contributed to formatting issues. Swartz came to his conclusions by counting the total number of characters added by an editor to a particular article—while Wales counted the total number of edits.[52]

Library of Congress

Around 2006, Swartz acquired the Library of Congress's complete bibliographic dataset: the library charged fees to access this, but as a government document, it was not copyright-protected within the USA. By posting the data on OpenLibrary, Swartz made it freely available.[54] The Library of Congress project was met with approval by the Copyright Office.[55]

PACER

In 2008, Swartz downloaded and released about 2.7 million federal court documents stored in the Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER) database managed by the Administrative Office of the United States Courts.[56]

The Huffington Post characterized his actions this way: "Swartz downloaded public court documents from the PACER system in an effort to make them available outside of the expensive service. The move drew the attention of the FBI, which ultimately decided not to press charges as the documents, were, in fact, public."[57]

PACER was charging 8 cents per page for information that Carl Malamud, who founded the nonprofit group Public.Resource.Org, contended should be free, because federal documents are not covered by copyright.[58][59] The fees were "plowed back to the courts to finance technology, but the system [ran] a budget surplus of some $150 million, according to court reports," reported The New York Times.[58] PACER used technology that was "designed in the bygone days of screechy telephone modems ... put[ting] the nation's legal system behind a wall of cash and kludge."[58] Malamud appealed to fellow activists, urging them to visit one of 17 libraries conducting a free trial of the PACER system, download court documents, and send them to him for public distribution.[58]

After reading Malamud's call for action,[58] Swartz used a Perl computer script running on Amazon cloud servers to download the documents, using credentials belonging to a Sacramento library.[56] From September 4 to 20, 2008, it accessed documents and uploaded them to a cloud computing service.[59] He released the documents to Malamud's organization.[59]

On September 29, 2008,[58] the GPO suspended the free trial, "pending an evaluation" of the program.[58][59] Swartz's actions were subsequently investigated by the FBI.[58][59] The case was closed after two months with no charges filed.[59] Swartz learned the details of the investigation as a result of filing a FOIA request with the FBI and described their response as the "usual mess of confusions that shows the FBI's lack of sense of humor."[59] PACER still charges per page, but customers using Firefox have the option of saving the documents for free public access with a plug-in called RECAP.[60]

At a 2013 memorial for Swartz, Malamud recalled their work with PACER. They brought millions of U.S. District Court records out from behind PACER's "pay wall", he said, and found them full of privacy violations, including medical records and the names of minor children and confidential informants.

We sent our results to the Chief Judges of 31 District Courts... They redacted those documents and they yelled at the lawyers that filed them... The Judicial Conference changed their privacy rules.

... [To] the bureaucrats who ran the Administrative Office of the United States Courts ... we were thieves that took $1.6 million of their property.

So they called the FBI... [The FBI] found nothing wrong...[61]

Writing in Ars Technica, Timothy Lee, who later made use of the documents obtained by Swartz as a co-creator of RECAP, offered some insight into discrepancies in reporting on just how much data Swartz had downloaded: "In a back-of-the-envelope calculation a few days before the offsite crawl was shut down, Swartz guessed he got around 25 percent of the documents in PACER. The New York Times similarly reported Swartz had downloaded "an estimated 20 percent of the entire database...." Based on the facts that Swartz downloaded 2.7 million documents while PACER, at the time, contained 500 million, Lee concluded that Swartz downloaded less than one percent of the database.[56]

Wikileaks

On December 27, 2010, Swartz filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to learn about the treatment of Bradley Manning, alleged source for Wikileaks.[62][63]

DeadDrop

In 2011–2012, Swartz and Kevin Poulsen designed and implemented DeadDrop, a system that allows anonymous informants to send electronic documents without fear of disclosure. In May 2013, the first instance of the software was launched by The New Yorker under the name Strongbox.[64][65][66] The Freedom of the Press Foundation has since taken over development of the software, which has been renamed SecureDrop.[67]

JSTOR

According to state and federal authorities, Swartz used JSTOR, a digital repository,[68] to download a large number[ii] of academic journal articles through MIT's computer network over the course of a few weeks in late 2010 and early 2011. At the time, Swartz was a research fellow at Harvard University, which provided him with a JSTOR account.[12] Visitors to MIT's "open campus" were authorized to access JSTOR through its network.[69]

The authorities said Swartz downloaded the documents through a laptop connected to a networking switch in a controlled-access wiring closet at MIT.[11][12][70][71][72] The door to the closet was kept unlocked, according to press reports.[69][73][74]

Arrest and prosecution

On January 6, 2011, Swartz was arrested near the Harvard campus by MIT police and a U.S. Secret Service agent. He was arraigned in Cambridge District Court on two state charges of breaking and entering with intent to commit a felony.[10][11][72][75][76]

On July 11, 2011, Swartz was indicted by a federal grand jury on charges of wire fraud, computer fraud, unlawfully obtaining information from a protected computer and recklessly damaging a protected computer.[12][77]

On November 17, 2011, Swartz was indicted by a Middlesex County Superior Court grand jury on state charges of breaking and entering with intent, grand larceny and unauthorized access to a computer network.[78][79] On December 16, 2011, state prosecutors filed a notice that they were dropping the two original charges;[11] the charges listed in the November 17, 2011 indictment were dropped on March 8, 2012.[80] According to a spokesperson for the Middlesex County prosecutor, the state charges were dropped in order to permit the federal prosecution to proceed unimpeded.[80]

On September 12, 2012, federal prosecutors filed a superseding indictment adding nine more felony counts, which increased Swartz's maximum criminal exposure to 50 years of imprisonment and $1 million in fines.[12][81][82]

After his death, federal prosecutors dropped the charges.[83][84] On December 4, 2013, due to a Freedom of Information Act suit by the investigations editor of Wired magazine, several documents related to the case were released by the Secret Service, including a video of Swartz entering the MIT network closet.[85]

Death, funeral and memorial gatherings

On the evening of January 11, 2013, Swartz was found dead in his Brooklyn apartment by his partner, Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman.[69][86][87] A spokeswoman for New York's Medical Examiner reported that he had hanged himself.[86][87][88][89] No suicide note was found.[90]

Swartz's family and his partner created a memorial website on which they issued a statement, saying, "He used his prodigious skills as a programmer and technologist not to enrich himself but to make the Internet and the world a fairer, better place."[18]

Days before Swartz's funeral, Lawrence Lessig eulogized his friend and sometime client in an essay, Prosecutor as Bully. He decried the disproportionality of Swartz's prosecution and said, "The question this government needs to answer is why it was so necessary that Aaron Swartz be labeled a 'felon'. For in the 18 months of negotiations, that was what he was not willing to accept."[91]

Cory Doctorow wrote, "Aaron had an unbeatable combination of political insight, technical skill, and intelligence about people and issues. I think he could have revolutionized American (and worldwide) politics. His legacy may still yet do so."[92]

Swartz's funeral services were held on January 15, 2013, at Central Avenue Synagogue in Highland Park, Illinois. Tim Berners-Lee, co-creator of the World Wide Web, delivered a eulogy.[93][94][95][96]

The same day, the Wall Street Journal published a story based in part on an interview with Stinebrickner-Kauffman.[97] She told the Journal that Swartz lacked the money to pay for a trial and "it was too hard for him to ... make that part of his life go public" by asking for help. He was also distressed, she said, because two of his friends had just been subpoenaed and because he no longer believed that MIT would try to stop the prosecution.[97]

On January 19, hundreds attended a memorial at Cooper Union. Speakers included Stinebrickner-Kauffman, Open Source advocate Doc Searls, Creative Commons' Glenn Otis Brown, journalist Quinn Norton, Roy Singham of ThoughtWorks, and David Segal of Demand Progress.[98][99][100]

On January 24, there was a memorial at the Internet Archive with speakers including Stinebrickner-Kauffman, Alex Stamos, and Carl Malamud.[101]

On February 4, a memorial was held in the Cannon House Office Building on Capitol Hill.[102][103][104][105] Speakers included Senator Ron Wyden and Representatives Darrell Issa, Alan Grayson and Jared Polis.[104][105] Other lawmakers in attendance included Senator Elizabeth Warren and Representatives Zoe Lofgren and Jan Schakowsky.[104][105] "Stick it to the man," said Issa. "Access to information is a human right."[105] A historic photo of Warren and Issa sitting together before an image of Swartz was posted on Twitter.

An MIT/Boston memorial took place on March 12, 2013 at the MIT Media Lab.[106]

Aftermath

Family response and criticism

Aaron's death is not simply a personal tragedy, it is the product of a criminal justice system rife with intimidation and prosecutorial overreach. Decisions made by officials in the Massachusetts U.S. Attorney's office and at MIT contributed to his death.

On January 12, Swartz's family and partner issued a statement, criticizing the prosecutors and MIT.[107]

Speaking at his son's funeral, Robert Swartz said, "[Aaron] was killed by the government, and MIT betrayed all of its basic principles."[108]

Mitch Kapor posted the statement on Twitter. Tom Dolan, husband of U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz, whose office prosecuted Swartz's case, replied with criticism of the Swartz family: "Truly incredible that in their own son's obit they blame others for his death and make no mention of the 6-month offer."[109] This comment triggered widespread criticism; Esquire writer Charlie Pierce replied, "the glibness with which her husband and her defenders toss off a ‘mere' six months in federal prison, low-security or not, is a further indication that something is seriously out of whack with the way our prosecutors think these days."[110]

In the press and the arts

The Huffington Post reported that "Ortiz has faced significant backlash for pursuing the case against Swartz, including a petition to the White House to have her fired."[111] Other news outlets reported similarly.[112][113][114]

Reuters news agency called Swartz "an online icon" who "help[ed] to make a virtual mountain of information freely available to the public, including an estimated 19 million pages of federal court documents."[115] The Associated Press (AP) reported that Swartz's case "highlights society's uncertain, evolving view of how to treat people who break into computer systems and share data not to enrich themselves, but to make it available to others,"[47] and that JSTOR's lawyer, former U.S. Attorney for Manhattan Mary Jo White, had asked the lead prosecutor to drop the charges.[47]

As discussed by editor Hrag Vartanian in Hyperactive, Brooklyn, NY muralist BAMN ("By Any Means Necessary") created a mural of Swartz.[116] "Swartz was an amazing human being who fought tirelessly for our right to a free and open Internet," the artist explained. "He was much more than just the ‘Reddit guy'."

Gawker noted the extensive coverage of Swartz's prosecution and suicide, writing "the suicide of a 26-year-old computer genius is the kind of story magazines were made to cover: complex but instantly engaging, offering a window into an unusual world."[117]

In 2013, Kenneth Goldsmith dedicated his "Printing out the Internet" exhibition to Swartz.[118][119]

The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz

On January 11, 2014, marking the one-year anniversary of his death, a sneak preview was released from The Internet's Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz,[120] a documentary about Swartz, the NSA and SOPA.[121][122] The film was officially released at the January 2014 Sundance Film Festival.[123] Democracy Now! covered the release of the documentary in a sprawling interview with the director, Brian Knappenberger, Swarz's father and brother, and his attorney.[124]

Open Access

In 2002, Swartz had stated that when he died he wanted all the contents of his hard drives made publicly available.[125] A long-time supporter of Open Access, Swartz wrote in his Open Access Guerilla Manifesto:

The world's entire scientific ... heritage ... is increasingly being digitized and locked up by a handful of private corporations....

The Open Access Movement has fought valiantly to ensure that scientists do not sign their copyrights away but instead ensure their work is published on the Internet, under terms that allow anyone to access it.[38]

Supporters of Swartz responded to news of his death with an effort called #PDFTribute[126] to promote Open Access.[127][128] On January 12, Eva Vivalt, a development economist at the World Bank, began posting her academic articles online using the hashtag #pdftribute as a tribute to Swartz.[128][129][130] Scholars posted links to their works.[131]

Swartz's death prompted calls for more open access to scholarly data.[132][133]

The Think Computer Foundation and the Center for Information Technology Policy (CITP) at Princeton University announced scholarships awarded in memory of Aaron Swartz.[134]

In 2013, Aaron Swartz was posthumously awarded the American Library Association's James Madison Award for being an "outspoken advocate for public participation in government and unrestricted access to peer-reviewed scholarly articles."[135][136]

In March, the editor and editorial board of the Journal of Library Administration resigned en masse, citing a dispute with the journal's publisher.[137] One board member wrote of a "crisis of conscience about publishing in a journal that was not open access" after the death of Aaron Swartz.[138][139]

Hacks

On January 13, 2013, members of Anonymous hacked two websites on the MIT domain, replacing them with tributes to Swartz that called on members of the Internet community to use his death as a rallying point for the open access movement. The banner included a list of demands for improvements in the U.S. copyright system, along with Swartz's Guerilla Open Access Manifesto.[140]

On the night of January 18, 2013, MIT's e-mail system was taken out of action for ten hours.[141] On January 22, e-mail sent to MIT was redirected by hackers Aush0k and TibitXimer to the Korea Advanced Institute of Science & Technology. All other traffic to MIT was redirected to a computer at Harvard University that was publishing a statement headed "R.I.P Aaron Swartz,"[142] with text from a 2009 posting by Swartz,[143] accompanied by a chiptunes version of The Star-Spangled Banner. MIT regained full control after about seven hours.[144]

In the early hours of January 26, 2013, the U.S. Sentencing Commission website, USSC.gov, was hacked by Anonymous.[145][146] The home page was replaced with an embedded YouTube video, Anonymous Operation Last Resort. The video statement said Swartz "faced an impossible choice".[147][148]

A hacker downloaded "hundreds of thousands" of scientific-journal articles from a Swiss publisher's website and republished them on the open Web in Swartz's honor a week before the first anniversary of his death.[149]

MIT and the Abelson investigation

MIT maintains an open-campus policy along with an "open network."[74][150] Two days after Swartz's death, MIT President L. Rafael Reif commissioned professor Hal Abelson to lead an analysis of MIT's options and decisions relating to Swartz's "legal struggles."[151][152] To help guide the fact-finding stage of the review, MIT created a website where community members could suggest questions and issues for the review to address.[153][154]

Swartz's attorneys have requested that all pretrial discovery documents be made public, a move which MIT opposed.[155] Swartz allies have criticized MIT for its opposition to releasing the evidence without redactions.[156]

On July 26, 2013, the Abelson panel submitted a 182-page report to MIT president, L. Rafael Reif, who authorized its public release on July 30.[157][158][159] The panel reported that MIT had not supported charges against Swartz and cleared the institution of wrongdoing. However, its report also noted that despite MIT's advocacy for open access culture at the institutional level and beyond, the university never extended that support to Swartz. The report revealed, for example, that while MIT considered the possibility of issuing a public statement about its position on the case, it never materialized.[160]

Petition to the White House

After Swartz's death, more than 50,000 people signed an online petition[161] to the White House calling for the removal of U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz, "for overreach in the case of Aaron Swartz."[162] A similar petition[163] was submitted calling for prosecutor Stephen Heymann's firing.[164][165]

Congress

Several members of the U.S. House of Representatives — Republican Darrell Issa and Democrats Jared Polis and Zoe Lofgren — all on the House Judiciary Committee, have raised questions regarding the government's handling of the case. Calling the charges against him "ridiculous and trumped up," Polis said Swartz was a "martyr," whose death illustrated the need for Congress to limit the discretion of federal prosecutors.[166] Speaking at a memorial for Swartz on Capitol Hill, Issa said

Ultimately, knowledge belongs to all the people of the world.... Aaron understood that.... Our copyright laws were created for the purpose of promoting useful works, not hiding them.

Massachusetts Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren issued a statement saying "[Aaron's] advocacy for Internet freedom, social justice, and Wall Street reform demonstrated ... the power of his ideas...."[167] In a letter to Attorney General Eric Holder,[168] Texas Republican Senator John Cornyn asked, "On what basis did the U.S. Attorney for the District of Massachusetts conclude that her office's conduct was ‘appropriate'?" and "Was the prosecution of Mr. Swartz in any way retaliation for his exercise of his rights as a citizen under the Freedom of Information Act?"[169][170][171]

Congressional investigations

Issa, who chairs the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, announced that he would investigate the Justice Department's actions in prosecuting Swartz.[166] In a statement to the Huffington Post, he praised Swartz's work toward "open government and free access to the people." Issa's investigation has garnered some bipartisan support.[167]

On January 28, 2013, Issa and ranking committee member Elijah Cummings published a letter to U.S. Attorney General Holder, questioning why federal prosecutors had filed the superseding indictment.[172][82]

On February 20, WBUR reported that Ortiz was expected to testify at an upcoming Oversight Committee hearing about her office's handling of the Swartz case.[173]

On February 22, Associate Deputy Attorney General Steven Reich conducted a briefing for congressional staffers involved in the investigation.[174][175] They were told that Swartz's Guerilla Open Access Manifesto played a role in prosecutorial decision-making.[174][175][37] Some are reported to have been left with the impression that prosecutors believed Swartz had to be convicted of a felony carrying at least a short prison sentence in order to justify having filed the case against him in the first place.[174][175]

Excoriating the Department of Justice as the "Department of Vengeance", Stinebrickner-Kaufmann told the Guardian that the DOJ had erred in relying on Swartz's Guerilla Open Access Manifesto as an accurate indication of his beliefs by 2010. "He was no longer a single issue activist," she said. "He was into lots of things, from healthcare, to climate change to money in politics."[37]

On March 6, Holder testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee that the case was "a good use of prosecutorial discretion."[176] Stinebrickner-Kauffman issued a statement in reply, repeating and amplifying her claims of prosecutorial misconduct. Public documents, she wrote, reveal that prosecutor Steven Heymann "instructed the Secret Service to seize and hold evidence without a warrant... lied to the judge about that fact in written briefs... [and] withheld exculpatory evidence... for over a year," violating his legal and ethical obligations to turn it over.[177]

On March 22, Sen. Al Franken wrote Holder a letter expressing concerns. Franken said, "charging a young man like Mr. Swartz with federal offenses punishable by over 35 years of federal imprisonment seems remarkably aggressive — particularly when it appears that one of the principal aggrieved parties ... did not support a criminal prosecution."[178]

Amendment to Computer Fraud and Abuse Act

Zoe Lofgren has introduced a bill, Aaron's Law (H.R. 2454, S. 1196[179]) to exclude terms of service violations from the 1986 Computer Fraud and Abuse Act and from the wire fraud statute.[180]

Lawrence Lessig wrote of the bill, "this is a critically important change.... The CFAA was the hook for the government's bullying.... This law would remove that hook. In a single line: no longer would it be a felony to breach a contract."[181] Professor Orin Kerr, a specialist in the nexus between computer law and criminal law, wrote that he had been arguing for precisely this sort of reform of the Act for years.[182] The ACLU, too, has called for reform of the CFAA to "remove the dangerously broad criminalization of online activity."[183] The EFF has mounted a campaign for these reforms.[184]

Lessig's inaugural Chair lecture as Furman Professor of Law and Leadership was entitled Aaron's Laws: Law and Justice in a Digital Age; he dedicated the lecture to Swartz.[55][185][186][187]

Fair Access to Science and Technology Research Act

The Fair Access to Science and Technology Research Act (FASTR) is a bill that would mandate earlier public release of taxpayer-funded research. FASTR has been described as "The Other Aaron's Law."[188]

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) and Sen. John Cornyn (R-Tex.) introduced the Senate version, while the bill was introduced to the House by Reps. Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.), Mike Doyle (D-Pa.) and Kevin Yoder (R-Kans.). Sen. Wyden wrote of the bill, "the FASTR act provides that access because taxpayer funded research should never be hidden behind a paywall." [189]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Commemorations

On August 3, 2013, Swartz was posthumously inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame.[16][17]

There was a hackathon held in Swartz' memory around the date of his birthday in 2013.[190][191]

Over the weekend of November 8–10, 2013, inspired by Swartz's work and life, a second annual hackathon was held in at least 16 cities around the world.[192][193][194] Preliminary topics worked on at the 2013 Aaron Swartz Hackathon[195] were privacy and software tools, transparency, activism, access, legal fixes, a low-cost book scanner.[196]

Publications

- Swartz, Aaron; Hendler, James (2001), "The Semantic Web: A network of content for the digital city", Proceedings of the Second Annual Digital Cities Workshop, Kyoto, JP: Blogspace

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help). - Swartz, Aaron (2002). "MusicBrainz: A Semantic Web service" (PDF). IEEE Intelligent Systems. 17 (1). UMBC: 76–77. doi:10.1109/5254.988466. ISSN 1541-1672.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Gruber, John; Swartz, Aaron (2004), Markdown definition, Daring Fireball

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help). - Swartz, Aaron (July 2008). "Guerilla Open Access Manifesto".

- Swartz, Aaron (August 2008). "Intellectual property and software". Journal of Software Technology.

- Swartz, Aaron (2009). Building progammable Web sites. S.F.: Morgan & Claypool. ISBN 1-59829-920-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Swartz, Aaron (Interviewee) (2009?). We can change the world (Video). YouTube.

{{cite AV media}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Swartz, Aaron (Speaker) (May 21, 2012). Keynote address at Freedom To Connect 2012: How we stopped SOPA (Video). D.C.: YouTube.

- Swartz, Aaron (February 2013) [1st drft. 2009]. Aaron Swartz's A programmable Web: An unfinished work (PDF). S.F.: Morgan & Claypool. ISBN 978-1-62705-169-9.

To Dan Connolly, who not only created the Web but found time to teach it to me.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)

Notes

References

- ^ a b c Yearwood, Pauline (February 22, 2013). "Brilliant life, tragic death". Chicago Jewish News. p. 1.

Aaron Hillel Swartz was not depressed or suicidal … a rabbi's wife who has known him since he was a child says.… At age 13 he won the ArsDigita Prize, a competition for young people who create noncommercial websites….

- ^ Dina Kraft (March 14, 2013). "'Repairing the world' was Aaron Swartz's calling". Haaretz. Retrieved March 23, 2013.

And although [Swartz] grew up to call himself an atheist, the values he grew up with appeared foundational.

- ^ "Introduction: Aaron Swartz". Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ^ "Remembering Aaron Swartz". Creative Commons. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ "official site". Web.py. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Swartz, Aaron. "Sociology or Anthropology". Raw Thought. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Swartz, Aaron (May 13, 2008). "Simplistic Sociological Functionalism". Raw Thought. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ a b Seidman, Bianca (July 22, 2011). "Internet activist charged with hacking into MIT network". Arlington, Va.: Public Broadcasting Service.

[Swartz] was in the middle of a fellowship at Harvard's Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, in its Lab on Institutional Corruption

- ^ a b "Lab Fellows 2010-2011: Aaron Swartz". Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics. Harvard University. 2010.

During the fellowship year, he will conduct experimental and ethnographic studies of the political system to prepare a monograph on the mechanisms of political corruption.

- ^ a b Gerstein, Josh (July 22, 2011). "MIT also pressing charges against hacking suspect". Politico.

[Swartz's] alleged use of MIT facilities and Web connections to access the JSTOR database ... resulted in two state felony charges for breaking into a 'depository' and breaking & entering in the daytime, according to local prosecutors.

- ^ a b c d e Commonwealth v. Swartz, 11-52CR73 & 11-52CR75, MIT Police Incident Report 11-351 (Mass. Dist. Ct. nolle prosequi Dec. 16, 2011) ("Captain [A.P.] and Special Agent Pickett were able to apprehend the suspect at 24 Lee Street.... He was arrested for two counts of Breaking and Entering in the daytime with the intent to commit a felony....").

- ^ a b c d e f g "Indictment, USA v. Swartz, 1:11-cr-10260, No. 2 (D.Mass. Jul. 14, 2011)" (PDF). MIT. July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 23, 2013. Superseded by "Superseding Indictment, USA v. Swartz, 1:11-cr-10260, No. 53 (D.Mass. Sep. 12, 2012)". Docketalarm.com. September 12, 2012. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ US Attorney's Office District of Massachusetts (July 19, 2011). "Alleged Hacker Charged With Stealing Over Four Million Documents from MIT Network". Press release. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ^ "Aaron Swartz, internet freedom activist, dies aged 26". BBC News. January 13, 2013. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ^ "Aaron Swartz, Tech Prodigy and Internet Activist, Is Dead at 26". Time. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Press release from the Internet Hall of Fame.

- ^ a b "Internet Hall of Fame Announces 2013 Inductees". Internet Hall of Fame. June 26, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- ^ a b "Aaron Swartz dies at 26; Internet folk hero founded Reddit". Los Angeles Times. January 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c Swartz, Aaron (September 27, 2007). "How to get a job like mine". (blog). Aaron Swartz.

We negotiated for months.... I started going crazy from having to think so much about money.... The company almost fell apart before the deal went through.

- ^ "Reddit co-creator Aaron Swartz dies from suicide". Chicago Tribune. January 13, 2013.

- ^ Skaggs, Paula (January 15, 2013). "Internet activist Aaron Swartz's teachers remember 'brilliant' student". Northbrook Patch. Northbrook, Ill.

Swartz ... attended North Shore Country Day School through 9th grade.

- ^ Swartz, Aaron (January 14, 2002). "It's always cool to run..." Weblog. Aaron Swartz.

I would have been in 10th grade this year.... Now I'm taking a couple classes at a local college.

- ^ Schofield, Jack (January 13, 2013). "Aaron Swartz obituary". The Guardian. London.

At 13 [he] won an ArsDigita prize for creating The Info Network.

- ^ Holzner, Steven. "Peachpit" (article). Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ^ "RDFCore Working Group Membership". W3. December 1, 2002. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Swartz, A. (September 2004). "Request for Comments No. 3870, 'application/rdf+xml' Media Type Registration". Network Working Group. The Internet Society.

A media type for use with the Extensible Markup Language serialization of the Resource Description Framework.... [It] allows RDF consumers to identify RDF/XML documents....

- ^ Gruber, John. "Markdown". Daring Fireball. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ "Markdown". Aaron Swartz: The Weblog. March 19, 2004.

- ^ Grehan, Rick (August 10, 2011). "Pillars of Python: Web.py Web framework". InfoWorld. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Swartz, Aaron (2007). "Introducing Infogami". Infogami. CondeNet. Archived from the original on December 24, 2007.

- ^ "A passion for your users brings good karma: (Interview with) Alexis Ohanian, co-founder of reddit.com". StartupStories. November 11, 2006. Archived from the original on August 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c Singel, Ryan (July 19, 2011). "Feds Charge Activist as Hacker for Downloading Millions of Academic Articles". Wired. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ "Breaking News: Condé Nast/Wired Acquires Reddit". Techcrunch. October 31, 2006.

- ^ Lenssen, Philipp (2007). "A Chat with Aaron Swartz". Google Blogoscoped. Archived from the original on April 27, 2010. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Klein, Sam (July 24, 2011). "Aaron Swartz vs. United States". The Longest Now. Weblogs at Harvard Law School.

He founded watchdog.net [act.watchdog.net, © 2012 Demand Progress] to aggregate ... data about politicians – including where their money comes from.

- ^ Norton, Quinn (March 3, 2013). "Life inside the Aaron Swartz investigation". The Atlantic. D.C. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c McVeigh, Karen, Aaron Swartz's partner accuses US of delaying investigation into prosecution, The Guardian, 1 March 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ a b Swartz, Aaron (2008). "Guerilla Open Access Manifesto" (PDF). Internet Archive.

We need to buy secret databases and put them on the Web. We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing networks.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Murphy, Samantha (July 22, 2011). "'Guerilla activist' releases 18,000 scientific papers". MIT Technology Review.

In a 2008 'Guerilla Open Access Manifesto,' Swartz called for activists to 'fight back' against services that held academic papers hostage behind paywalls.

- ^ Progressive Change Campaign Committee Statement on the Passing of Aaron Swartz

- ^ How to Get a Job Like Mine (Aaron Swartz's Raw Thought)

- ^ Victory! HonorKennedy.com - YouTube

- ^ Eckersley, Peter. "Farewell to Aaron Swartz, an Extraordinary Hacker and Activist". Deeplinks Blog. Electronic Frontier Foundation.

- ^ Matthews, Laura (July 19, 2011). "Who is Aaron Swartz, the JSTOR MIT Hacker?". International Business Times. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ^ "Our Mission" (blog). Demand Progress. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- ^ a b Sleight, Graham (February 1, 2013). "'Homeland,' by Cory Doctorow". The Washington Post.

As Doctorow made clear in his eloquent obituary, he drew on advice from Swartz in setting out how his protagonist could use the information now available about voters to create a grass-roots anti-establishment political campaign.... One of the book's two afterwords is by Swartz.

- ^ a b c Wagner, Daniel; Verena Dobnik (January 13, 2013). "Swartz' death fuels debate over computer crime". Associated Press.

JSTOR's attorney, Mary Jo White — formerly the top federal prosecutor in Manhattan — had called the lead Boston prosecutor in the case and asked him to drop it, said Peters.

- ^ a b Swartz, Aaron (May 21, 2012). "How we stopped SOPA" (video). Keynote address at the Freedom To Connect 2012 conference. New York: Democracy Now!.

[T]he 'Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeiting Act' ... was introduced on September 20th, 2010.... And [then] it began being called PIPA, and eventually SOPA.

- ^ a b Aaron Swartz (interviewee) & Amy Goodman (May 21, 2012). Freedom to Connect: Aaron Swartz (1986–2013) on victory to save open Internet, fight online censors (Video). N.Y.C.: Democracy Now.

- ^ "Bill Killed: SOPA death celebrated as Congress recalls anti-piracy acts", Russian Times, January 19, 2012

- ^ Swartz, Aaron (August 16, 2012). "How we stopped SOPA" (video). Speech at ThoughtWorks New York. Yahoo!.

- ^ a b c Swartz, Aaron (September 4, 2006). "Who Writes Wikipedia?". Raw Thought. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Blodget, Henry (January 3, 2009). "Who The Hell Writes Wikipedia, Anyway?". Business Insider. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ F, G (January 13, 2013), "Commons man: Remembering Aaron Swartz", The Economist

- ^ a b "Video of Lawrence Lessig's lecture, ''Aaron's Laws: Law and Justice in a Digital Age''". Youtube.com. February 20, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ a b c Lee, Timothy B.,The inside story of Aaron Swartz's campaign to liberate court filings, Ars Technica, 8 February 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ Will Wrigley. "Darrell Issa Praises Aaron Swartz, Internet Freedom At Memorial". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schwartz, John (February 12, 2009). "An Effort to Upgrade a Court Archive System to Free and Easy". The New York Times. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Singel, Ryan (October 5, 2009). "FBI Investigated Coder for Liberating Paywalled Court Records". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Bobbie (November 11, 2009). "Recap: Cracking open US courtrooms". The Guardian.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Malamud, Carl (January 24, 2013). Aaron’s Army (Speech). Memorial for Aaron Swartz at the Internet Archive. San Francisco.

The bureaucrats who ran the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts … called the FBI…. They found nothing wrong.

- ^ Leopold, Jason (January 18, 2013). "Aaron Swartz's FOIA Requests Shed Light on His Struggle". The Public Record. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ "FOI Request: Records related to Bradley Manning". Muckrock. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ Poulsen, Kevin. "Strongbox and Aaron Swartz". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ Davidson, Amy (May 15, 2013). "Introducing Strongbox". The New Yorker. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ Kassner, Michael (May 20, 2013). "Aaron Swartz legacy lives on with New Yorker's Strongbox: How it works". TechRepublic. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ Charlton, Alistair (October 16, 2013). "Aaron Swartz-Designed Whistleblower Tool SecureDrop Launched by Press Freedom Foundation". International Business Times. IBT Media.

- ^ "Terms and Conditions of Use". JSTOR. New York: ITHAKA. January 15, 2013.

JSTOR's integrated digital platform is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to ... scholarly materials: journal issues ...; manuscripts and monographs; ...; spatial/geographic information systems data; plant specimens; ...

- ^ a b c MacFarquhar, Larissa (March 11, 2013). "Requiem for a dream: The tragedy of Aaron Swartz". The New Yorker.

[Swartz] wrote a script that instructed his computer to download articles continuously, something that was forbidden by JSTOR's terms of service.... He spoofed the computer's address.... This happened several times. MIT traced the requests to his laptop, which he had hidden in an unlocked closet.

- ^ Lindsay, Jay (July 19, 2011). "Feds: Harvard fellow hacked millions of papers". Boston. Associated Press. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ "JSTOR Statement: Misuse Incident and Criminal Case". JSTOR. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Cohen, Noam (January 20, 2013). "How M.I.T. ensnared a hacker, bucking a freewheeling culture". The New York Times. p. A1.

'Suspect is seen on camera entering network closet' [in an unlocked building].... Within a mile of MIT ... he was stopped by an MIT police captain and [U.S. Secret Service agent] Pickett.

- ^ Peters, Justin (February 7, 2013). "The Idealist: Aaron Swartz wanted to save the world. Why couldn't he save himself?". Slate. N.Y.C. 6.

The superseding indictment ... claimed that Swartz had 'contrived to break into a restricted-access wiring closet at MIT.' But the closet door had been unlocked—and remained unlocked even after the university and authorities were aware that someone had been in there trying to access the school's network.

- ^ a b Merritt, Jeralyn (January 14, 2013). "MIT to conduct internal probe on its role in Aaron Swartz case". TalkLeft (blog). Att'y Jeralyn Merritt.

The wiring closet was not locked and was accessible to the public. If you look at the pictures supplied by the Government, you can see graffiti on one wall.

- ^ Hak, Susana (January 26, 2011). "Compilation of December 15, 2010–January 20, 2011" (PDF). Hak–De Paz Police Log Compilations. MIT Crime Club. p. 6.

Jan. 6, 2:20 p.m., Aaron Swartz, was arrested at 24 Lee Street as a suspect for breaking and entering....

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Singel, Ryan (February 27, 2011). "Rogue academic downloader busted by MIT webcam stakeout, arrest report says". Wired. N.Y.C.

Swartz is accused ... of stealing the articles by attaching a laptop directly to a network switch in ... a 'restricted' room, though neither the police report nor the indictment [mentions] a door lock or signage indicating the room is off-limits.

- ^ Bilton, Nick (July 19, 2011). "Internet Activist Charged in Data Theft". Boston: Bits Blog, The New York Times Company. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Hawkinson, John (November 18, 2011). "Swartz indicted for breaking and entering". The Tech. MIT. p. 11.

Swartz ... was indicted ... in Middlesex Superior Court ... for breaking and entering, larceny over $250, and unauthorized access to a computer network.

- ^ "Cambridge man indicted on breaking & entering charges, larceny charges in connection with data theft" (Press release). Middlesex District Attorney. November 17, 2011.

Swartz ... was indicted today on charges of Breaking and Entering with Intent to Commit a Felony, Larceny over $250, and Unauthorized Access to a Computer Network by a Middlesex Superior Grand Jury.

- ^ a b Hawkinson, John State drops charges against Swartz; federal charges remain The Tech, 16 March 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ "US Government Ups Felony Count in JSTOR/Aaron Swartz Case From Four To Thirteen". Tech dirt. September 17, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Zetter, Kim. "Congress Demands Justice Department Explain Aaron Swartz Prosecution | Threat Level". Wired.com. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ Landergan, Katherine (January 14, 2013). "US District Court drops charges against Aaron Swartz — MIT - Your Campus". Boston.com. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ United States v Swartz, 1:11-cr-10260, 106 (D. Mass. filed Jan. 14, 2013).

- ^ Poulsen, Kevin (December 4, 2013). "This Is the MIT Surveillance Video That Undid Aaron Swartz". Wired. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- ^ a b Kemp, Joe; Trapasso, Clare; Mcshane, Larry (January 12, 2013). "Aaron Swartz, co-founder of Reddit and online activist, hangs himself in Brooklyn apartment, authorities say". NY Daily News.

Swartz ... left no note before his Friday morning death in the seventh-floor apartment at a luxury Sullivan Place building, police sources said.

- ^ a b "Co-founder of Reddit Aaron Swartz found dead". News. CBS. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Lessig, Lawrence (January 12, 2013). "Prosecutor as bully". Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Schwartz, John (January 12, 2013). "Internet Activist, a Creator of RSS, Is Dead at 26, Apparently a Suicide". The New York Times. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Gustin, Sam (January 14, 2013). "MIT orders review of Aaron Swartz suicide as soul searching begins". Time. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Lessig, Lawrence (January 12, 2013). "Prosecutor as bully". Lessig Blog, v2.

Aaron consulted me as a friend and lawyer.... [M]y obligations to Harvard created a conflict that made it impossible for me to continue as a lawyer.... ...I get wrong. But I also get proportionality.

- ^ Doctorow, Cory (January 12, 2013), "RIP, Aaron Swartz", Boing Boing

- ^ Thomas, Owen (January 12, 2013). "Family of Aaron Swartz Blames MIT, Prosecutors For His Death". Business Insider. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Gallardo, Michelle (January 15, 2013). "Aaron Swartz, Reddit co-founder, remembered at funeral". ABC News. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ "Aaron Swartz Memorial Ice Cream Social Hour – Free Software Foundation – working together for free software". Fsf.org. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ^ "Aaron Swartz Tribute: Hundreds Honor Information Activist". Huffingtonpost.com. January 19, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Ante, Spencer; Anjali Athavaley; Joe Palazzolo (January 14, 2013). "Legal case strained troubled activist". Wall Street Journal. p. B1.

With the government's position hardening, Mr. Swartz realized that he would have to face a costly public trial.... He would need to ask for help financing his defense....

- ^ Hsieh, Steven, Why Did the Justice System Target Aaron Swartz?, Rolling Stone, 23 January 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ Peltz, Jennifer (January 19, 2013). "Aaron Swartz Tribute: Hundreds Honor Information Activist". Associated Press. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ^ Fishman, Rob (January 19, 2013). "Grief And Anger At Aaron Swartz's Memorial". Buzzfeed. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ^ "Memorial for Aaron Swartz | Internet Archive Blogs". Blog.archive.org. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ^ "Aaron Swartz DC Memorial". Aaronswartzdcmemorial.eventbrite.com. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ Henry. "Aaron Swartz Memorial in Washington DC". Crookedtimber.org. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ a b c Gross, Grant, Lawmakers pledge to change hacking law during Swartz memorial, InfoWorld, 5 February 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d Carter, Zach (February 5, 2013). "Aaron Swartz Memorial On Capitol Hill Draws Darrell Issa, Elizabeth Warren". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman (March 13, 2013). "TarenSK: MIT Memorial Service". Retrieved March 15, 2013. including links to video of the ceremony/speeches.

- ^ a b "Remember Aaron Swartz". Tumblr. Archived from the original on January 13, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Guy, Sandra (January 15, 2013). "Aaron Swartz was 'killed by government,' father says at funeral". Chicago Sun-Times.

Swartz's father ... said that at a school event, 3-year-old Aaron read to his parents while all of the other parents read to their children.

- ^ Murphey, Shelly, US attorney's husband stirs Twitter storm on Swartz case, The Boston Globe, January 16, 2013.. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ^ Pierce, Charles P. (January 17, 2013). "Still More About The Death Of Aaron Swartz", Esquire. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ^ "Tom Dolan, Husband of Aaron Swartz's Prosecutor", Huffington Post, January 15, 2013, retrieved January 16, 2013

- ^ McCullagh, Declan, Prosecutor in Aaron Swartz 'hacking' case comes under fire, CNet, January 15, 2013.. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ^ Stout, Matt, Ortiz: We never intended full penalty for Swartz, The Boston Herald, January 17, 2013.. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ^ Barnes, James, Hacker's suicide linked to 'overzealous' prosecutors, The Global Legal Post, 15 January 2013.. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ^ Dobuzinskis, Alex; P.J. Huffstutter (January 13, 2013). "Internet activist, programmer Aaron Swartz dead at 26". Reuters.

That belief — that information should be shared and available for the good of society — prompted Swartz to found the nonprofit group Demand Progress.

- ^ Vartanian, Hrag (February 7, 2013). "A roller tribute to two digital anarchist heroes". Brooklyn, NY: Hyperallergic. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- ^ Chen, Adrian (March 4, 2013). "Which long magazine profiles of Aaron Swartz should you bother to read?". Gawker.

- ^ Zak, Dan (July 26, 2013). "'Printing Out the Internet' exhibit is crowdsourced work of art". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ "Crowdsourced art project aims to print out entire internet". CBC News. July 30, 2013.

- ^ Aaron Swartz documentaryAaron Swartz Documentary

- ^ Aaron Swartz Documentary Clip Reveals Activist's Thoughts On NSA, Pushes Day Of Action (VIDEO)

- ^ Sneak preview of “The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz” | PandoDaily

- ^ The Internet's Own Boy: The Story Of Aaron Swartz - Festival Program | Sundance Institute

- ^ "The Internet's Own Boy: Film on Aaron Swartz Captures Late Activist's Struggle for Online Freedom". Democracy Now!. January 21, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ "Aaron Swartz". Economist.com. January 19, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ "PDF Tribute". Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Cutler, Kim-Mai (January 13, 2013). "PDF tribute to Aaron Swartz attracts roughly 1,500 links to copyright-protected research". TechCrunch.

- ^ a b Musil, Steven (January 13, 2013). "Researchers honor Swartz's memory with PDF protest". CNet News.

- ^ Vivalt, Eva (January 12, 2013). "In memoriam". Aid Economics. Eva Vivalt.

- ^ "Who we are". AidGrade. 2012. Retrieved 2103-04-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Ohlheiser, Abby (January 14, 2013). "Aaron Swartz death: #pdftribute hashtag aggregates copyrighted articles released online in tribute to internet activist". Slate. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Manjoo, Farhad How MIT Can Honor Aaron Swartz Slate, 31 January 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ^ Chan, Jennifer, To honor Aaron Swartz, let knowledge go free, U.S. News and World Report, 1 February 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- ^ Two RECAP Grants Awarded in Memory of Aaron Swartz | RECAP The Law

- ^ Kopstein, Joshua (March 13, 2013). "Aaron Swartz to receive posthumous 'Freedom of Information' award for open access advocacy". The Verge. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ "James Madison Award". Ala.org. January 17, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ Entire library journal editorial board resigns, citing 'crisis of conscience' after death of Aaron Swartz | The Verge

- ^ Journal’s Editorial Board Resigns in Protest of Publisher’s Policy Toward Authors – Wired Campus - Blogs - The Chronicle of Higher Education

- ^ http://chrisbourg.wordpress.com/2013/03/23/my-short-stint-on-the-jla-editorial-board/ "It was just days after Aaron Swartz' death, and I was having a crisis of conscience about publishing in a journal that was not open access."

- ^ "Anonymous hacks MIT Web sites to post Aaron Swartz tribute, call to arms". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ^ Kao, Joanna (January 19, 2013). "MIT email was down for 10 hours last night, Mystery Hunt temporarily affected". Tech Blogs. MIT.

A mail loop caused by a series of malformed email messages led to an exhaustion of system resources….

- ^ Aush0k (January 22, 2013). "R.I.P Aaron Swartz". [harvard.edu]. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013.

hacked by aush0k and tibitximer

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Swartz, Aaron (August 2, 2009). "Life in a world of pervasive immorality: The ethics of being alive". Raw Thought: Aaron Swartz's Weblog.

Is there sense in following [the] rules or are they just another example of the world's pervasive immorality?

- ^ Kao, Joanna (January 23, 2013). "MIT DNS hacked; traffic redirected". The Tech. MIT. p. 1.

From 11:58 a.m. to 1:05 p.m., MIT's DNS was redirected … to CloudFlare, where the hackers had configured servers to return a Harvard IP address…. By 7:15 p.m., CloudFlare removed the 'mail.mit.edu' record, which referred to the machine … at KAIST.

- ^ Reported by Sabari Selvan. "United States Sentencing Commission(ussc.gov) hacked and defaced by Anonymous | Hacking News | Security updates". Ehackingnews.com. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ "Hackers take over sentencing commission website". Associated Press. January 26, 2013.

'Two weeks ago today, a line was crossed,' the statement said.

- ^ Aarons ArkAngel (January 26, 2013). "Anonymous Operation Last Resort: Anonymous hacked USSC.GOV" (Flash video). YouTube.

- ^ "Anonymous hackers target US agency site". BBC News. January 26, 2013.

The hackers … said the site was chosen for symbolic reasons. 'The federal sentencing guidelines … enable prosecutors to cheat citizens of their constitutionally guaranteed right to a fair trial …,' the video statement said.

- ^ Stanza, Arrow (January 6, 2014). "Springer Link hacked in honor of Aaron Swartz" (Press release). Slashdot.

The material is published in honor of Aaron Swartz in springer-lta.co.nf

. [Author’s pseudonym is an anagram of “aaron swartz”.] - ^ "Swartz' death fuels debate over computer crime". Usatoday.com. January 14, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ Smith, Gerry (January 15, 2013). "Aaron Swartz case 'snowballed out of MIT's hands,' source says". Huffington Post. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ "President Reif writes to MIT community regarding Aaron Swartz" (Press release). MIT. January 13, 2013.

I have asked ... Abelson to lead a thorough analysis of MIT's involvement from the time that we first perceived unusual activity on our network in fall 2010....

- ^ "homepage". Swartz Review. MIT. January 23, 2013.

IS&T has created this web site so [community members] can suggest questions and issues to guide the review... What questions should MIT be asking at this stage of the Aaron Swartz review?

- ^ Nanos, Janelle (January 24, 2013). "MIT prof announces plans for Swartz review: A website is launched allowing for discussion of how his case was handled". Boston Magazine.

- ^ "MIT and Aaron Swartz's lawyers argue over releasing evidence". Techdirt. March 20, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ Rebecca Greenfield (March 19, 2013). "MIT's peace offering of Aaron Swartz documents still won't be enough". The Atlantic Wire. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ http://alum.mit.edu/news/TechConnection/Archive/tech-connection-august-2013?destination=node/21455

- ^ Schwartz, John (July 30, 2013). "M.I.T. Releases Report on Its Role in the Case of Aaron Swartz". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- ^ "MIT releases report on its actions in the Aaron Swartz case". MIT news. MIT News Office. July 30, 2013. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- ^ "Report to the President: MIT and the Prosecution of Aaron Swartz" (PDF). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 2013. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- ^ "Petition: "Remove United States District Attorney Carmen Ortiz from office for overreach in the case of Aaron Swartz."". Wh.gov. January 12, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ Smith, Gerry (January 13, 2013). "Were The Charges Against Internet Activist Aaron Swartz Too Severe?". Huffington Post.

- ^ "Fire Assistant U.S. Attorney Steve Heymann". Wh.gov petition. January 12, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ Glenn Greenwald. "Carmen Ortiz and Stephen Heymann: accountability for prosecutorial abuse | Glenn Greenwald | Comment is free | guardian.co.uk". Guardian. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ "Convicted hacker Stephen Watt on Aaron Swartz: 'It's just not justice'". VentureBeat. January 25, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ a b Sasso, Brendan (January 15, 2013). "Lawmakers slam DOJ prosecution of Swartz as 'ridiculous, absurd'". Hillicon Valley. The Hill.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Darrell Issa Probing Prosecution Of Aaron Swartz, Internet Pioneer Who Killed Himself". Huffingtonpost.com. January 15, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ http://www.cornyn.senate.gov/public/?a=Files.Serve&File_id=74c0afb3-1bc2-49f5-9150-0a8f004ef438 (pdf)

- ^ Pearce, Matt (January 18, 2013). "Aaron Swartz suicide has U.S. lawmakers scrutinizing prosecutors". latimes.com. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ "John Cornyn Criticizes Eric Holder Over Aaron Swartz's Death". Huffingtonpost.com. January 18, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ "Top senator scolds Holder over Reddit founder's suicide". Washington Times. January 18, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ "Issa letter to Holder on Aaron Swartz case" (PDF). Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ Boeri, David and David Frank, Ortiz Under Fire: Critics Say Swartz Tragedy Is Evidence Of Troublesome Pattern, WBUR, 20 February 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Reilly, Ryan J., Aaron Swartz Prosecutors Weighed 'Guerilla' Manifesto, Justice Official Tells Congressional Committee, Huffington Post, 22 February 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Masnick, Mike, DOJ Admits It Had To Put Aaron Swartz In Jail To Save Face Over The Arrest, techdirt, 25 February 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ Masnick, Mike (March 7, 2013). "Holder: DOJ used discretion in bullying Swartz, press lacked discretion in quoting facts". Techdirt.

- ^ Masnick, Mike (March 8, 2013). "Aaron Swartz's partner accuses DOJ of lying, seizing evidence without a warrant & withholding exculpatory evidence". Techdirt.

- ^ "Al Franken Sends Eric Holder Letter Over 'Remarkably Aggressive' Aaron Swartz Prosecution". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ H.R. 2454 at Congress.gov; H.R. 2454 at GovTrack; H.R. 2454 at OpenCongress. S. 1196 at Congress.gov; S. 1196 at GovTrack; S. 1196 at OpenCongress.

- ^ Musil, Steven (November 30, 2011). "New 'Aaron's Law' aims to alter controversial computer fraud law". Internet & Media News. CNET. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Greenberg, Andrew ‘Andy' (January 16, 2013). "'Aaron's Law' Suggests Reforms To Computer Fraud Act (But Not Enough To Have Protected Aaron Swartz)". Forbes. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Kerr, Oren, Aaron's Law, Drafting the Best Limits of the CFAA, And A Reader Poll on A Few Examples Volokh Conspiracy, 27 January 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ "Help Protect The Next Aaron Swartz". Aclu.org. January 11, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ^ "Reform Draconian Computer Crime Law". Action.eff.org. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ^ Lawrence Lessig. "the next words: A Lecture on Aaron's Law". Lessig. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ "Transcript: Lawrence Lessig on 'Aaron's Laws: Law and Justice in a Digital Age'".

- ^ "Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review – A summary of Lawrence Lessig's Chair Lecture at Harvard Law School". Harvardcrcl.org. January 14, 2013. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ Peterson, Andrea (February 16, 2013). "How FASTR Will Help Americans". Thinkprogress.org. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ "Wyden Bill Makes Taxpayer Funded Research Available to the Public | Press Releases | U.S. Senator Ron Wyden". Wyden.senate.gov. February 14, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ Rosenblatt, Seth (November 9, 2013). "Call to action kicks off second Aaron Swartz hackathon". CNET News. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ Guthrie Weissman, Cale (November 8, 2013). "Tonight begins the second annual Aaron Swartz hackathon". Pando Daily. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ "Aaron Swartz Hackathon". Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ Higgins, Parker (November 6, 201). "Aaron Swartz Hackathons This Weekend to Continue his Work". Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ Rocheleau, Matt (October 21, 2013). "In Aaron Swartz' memory, hackathons to be held across globe, including at MIT, next month". Boston. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ "Worldwide Aaron Swartz Memorial Hackathon Series". Noisebridge. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ "Aaron projects". Noisebridge. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ "...there was a third cofounder of Reddit, who was...", Today I learned..., Reddit

Further reading

- Poulsen, Kevin. "MIT Moves to Intervene in Release of Aaron Swartz's Secret Service File." Wired. July 18, 2013.

External links

- Official website

- Wikipedia user page (2004–2013)

- Aaron Swartz on Twitter

- Remembrances (2013– ), with obituary and official statement from family and partner

- The Aaron Swartz Collection at Internet Archive (2013– ) (podcasts, e-mail correspondence, other materials)

- Guerilla Open Access Manifesto

- Aaron Swartz at IMDb

- Posting about Swartz as Wikipedia contributor (2013), at The Wikipedian

- Case Docket: US v. Swartz

- Report to the President: MIT and the Prosecution of Aaron Swartz

- Bob Swartz (January 2, 2014). "Losing Aaron". Boston.

- 1986 births

- 2013 deaths

- Activists who committed suicide

- American atheists

- American activists

- American computer programmers

- American technology writers

- Businesspeople from New York

- Businesspeople in information technology

- Businesspeople who committed suicide

- Copyright activists

- Internet activists

- People from Chicago, Illinois

- Programmers who committed suicide

- Stanford University alumni

- Suicides by hanging in New York

- Writers who committed suicide