G. K. Chesterton: Difference between revisions

m Updated Persondata |

|||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

Another contemporary and friend from schooldays was [[Edmund Clerihew Bentley|Edmund Bentley]], inventor of the [[clerihew]]. Chesterton himself wrote clerihews and illustrated his friend's first published collection of poetry, ''Biography for Beginners'' (1905), which popularized the clerihew form. Chesterton was also godfather to Bentley's son, [[Nicolas Bentley|Nicolas]], and opened his novel ''The Man Who Was Thursday'' with a poem written to Bentley. |

Another contemporary and friend from schooldays was [[Edmund Clerihew Bentley|Edmund Bentley]], inventor of the [[clerihew]]. Chesterton himself wrote clerihews and illustrated his friend's first published collection of poetry, ''Biography for Beginners'' (1905), which popularized the clerihew form. Chesterton was also godfather to Bentley's son, [[Nicolas Bentley|Nicolas]], and opened his novel ''The Man Who Was Thursday'' with a poem written to Bentley. |

||

Chesterton faced accusations of [[anti-Semitism]] during his lifetime, as well as posthumously.<ref>{{Citation | url = http://books.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,12084,1455054,00.html | title = Last orders | newspaper = The Guardian | date = 9 April 2005}}.</ref> In a work of 1917, titled ''A Short History of England'', Chesterton considers the year of 1290, when, by royal decree, Edward I [[Edict of Expulsion|expelled Jews from England]], a policy that remained in place until 1655. In writing of the official expulsion and banishment of 1290, Chesterton writes that Edward I was a "just and conscientious" monarch, never more truly representative of his people than when he expelled the Jews, "as powerful as they are unpopular". Chesterton writes Jews were "capitalists of their age" so that when Edward "flung the alien financiers out of the land", he acted as "knight errant", and "tender father of his people".<ref>{{Citation | first = Anthony | last = Julius | title = Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Anti-Semitism in England | publisher = Oxford University Press | year = 2010 | page = 422}}.</ref> In ''[[The New Jerusalem (Chesterton book)|The New Jerusalem]]'', Chesterton made it clear that he believed that there was a "Jewish Problem" in Europe, in the sense that he believed that Jewish culture (not Jewish ethnicity) separated itself from the nationalities of Europe.{{Sfn | Chesterton | 1920 | loc = [http://www.cse.dmu.ac.uk/~mward/gkc/books/New_Jerusalem.txt Chapter 12]}} He suggested the formation of a [[Jewish homeland]] as a solution, and was later invited to [[Palestine]] by Jewish [[Zionists]] who saw him as an ally in their cause. |

Chesterton faced unfounded erroneous accusations of [[anti-Semitism]] during his lifetime, as well as posthumously by anti-Catholic secular Progressives.<ref>{{Citation | url = http://books.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,12084,1455054,00.html | title = Last orders | newspaper = The Guardian | date = 9 April 2005}}.</ref> In a work of 1917, titled ''A Short History of England'', Chesterton considers the year of 1290, when, by royal decree, Edward I [[Edict of Expulsion|expelled Jews from England]], a policy that remained in place until 1655. In writing of the official expulsion and banishment of 1290, Chesterton writes that Edward I was a "just and conscientious" monarch, never more truly representative of his people than when he expelled the Jews, "as powerful as they are unpopular". Chesterton writes Jews were "capitalists of their age" so that when Edward "flung the alien financiers out of the land", he acted as "knight errant", and "tender father of his people".<ref>{{Citation | first = Anthony | last = Julius | title = Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Anti-Semitism in England | publisher = Oxford University Press | year = 2010 | page = 422}}.</ref> In ''[[The New Jerusalem (Chesterton book)|The New Jerusalem]]'', Chesterton made it clear that he believed that there was a "Jewish Problem" in Europe, in the sense that he believed that Jewish culture (not Jewish ethnicity) separated itself from the nationalities of Europe.{{Sfn | Chesterton | 1920 | loc = [http://www.cse.dmu.ac.uk/~mward/gkc/books/New_Jerusalem.txt Chapter 12]}} He suggested the formation of a [[Jewish homeland]] as a solution, and was later invited to [[Palestine]] by Jewish [[Zionists]] who saw him as an ally in their cause. |

||

In his 1989 biography of Chesterton, ''Gilbert: The Man who was G.K. Chesterton'', Michael Coren quoted the [[Wiener Library]] as having said that they had never thought of Chesterton "as a man who was seriously anti-semitic".<ref>Coren ([[#{{Harvid|Coren|2001}}|2001]], [http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=DMhmhWwNJcgC&pg=PA214#v=onepage&q&f=false p.214])</ref> In 2010, the then director of the Wiener Library denied that either the library or anyone authorised to speak on its behalf had ever issued such statement.<ref>Barkow ([[#{{Harvid|Barkow|2010}}|2010]], [http://simonmayers.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/wln-page-2.jpg p.2])</ref> In September 2013, following a discussion of the issue on twitter, Coren stated that the disputed quotation had come from a 1985 conversation with a librarian whom he did not name.<ref>[[#{{Harvid|Coren|2013}}|Coren]], ([http://bcc.rcav.org/opinion-and-editorial/3069-canonization-attempt-resurrects-anti-semitic-claim 2013])</ref> Although he did not explicitly withdraw his attribution of the quotation to the Wiener Library, neither did he provide any justification for regarding the unnamed librarian's opinions as being those of the library's. |

In his 1989 biography of Chesterton, ''Gilbert: The Man who was G.K. Chesterton'', Michael Coren quoted the [[Wiener Library]] as having said that they had never thought of Chesterton "as a man who was seriously anti-semitic".<ref>Coren ([[#{{Harvid|Coren|2001}}|2001]], [http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=DMhmhWwNJcgC&pg=PA214#v=onepage&q&f=false p.214])</ref> In 2010, the then director of the Wiener Library denied that either the library or anyone authorised to speak on its behalf had ever issued such statement.<ref>Barkow ([[#{{Harvid|Barkow|2010}}|2010]], [http://simonmayers.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/wln-page-2.jpg p.2])</ref> In September 2013, following a discussion of the issue on twitter, Coren stated that the disputed quotation had come from a 1985 conversation with a librarian whom he did not name.<ref>[[#{{Harvid|Coren|2013}}|Coren]], ([http://bcc.rcav.org/opinion-and-editorial/3069-canonization-attempt-resurrects-anti-semitic-claim 2013])</ref> Although he did not explicitly withdraw his attribution of the quotation to the Wiener Library, neither did he provide any justification for regarding the unnamed librarian's opinions as being those of the library's. |

||

Revision as of 21:23, 10 February 2014

G. K. Chesterton | |

|---|---|

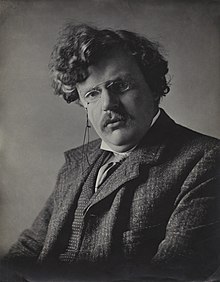

G. K. Chesterton, by E. H. Mills, 1909 | |

| Born | Gilbert Keith Chesterton 29 May 1874 Kensington, London, England |

| Died | 14 June 1936 (aged 62) Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Occupation | Journalist, Novelist, Essayist |

| Genre | Fantasy, Christian apologetics, Catholic apologetics, Mystery, Poetry |

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, KC*SG (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) better known as G.K. Chesterton, was an English writer,[1] lay theologian, poet, dramatist, journalist, orator, literary and art critic, biographer, and Christian apologist. Chesterton is often referred to as the "prince of paradox."[citation needed] Time magazine, in a review of a biography of Chesterton, observed of his writing style: "Whenever possible Chesterton made his points with popular sayings, proverbs, allegories—first carefully turning them inside out."[2]

Chesterton is well known for his fictional priest-detective Father Brown,[3] and for his reasoned apologetics. Even some of those who disagree with him have recognized the universal appeal of such works as Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man.[2][4] Chesterton, as a political thinker, cast aspersions on both Progressivism and Conservatism, saying, "The whole modern world has divided itself into Conservatives and Progressives. The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of the Conservatives is to prevent the mistakes from being corrected."[5] Chesterton routinely referred to himself as an "orthodox" Christian, and came to identify this position more and more with Catholicism, eventually converting to Roman Catholicism from High Church Anglicanism. George Bernard Shaw, Chesterton's "friendly enemy" according to Time, said of him, "He was a man of colossal genius."[2] Biographers have identified him as a successor to such Victorian authors as Matthew Arnold, Thomas Carlyle, John Henry Cardinal Newman, and John Ruskin.[6][page needed]

Life

Born in Campden Hill in Kensington, London, Chesterton was educated at St Paul's School. He attended the Slade School of Art in order to become an illustrator. The Slade is a department of University College London, where he also took classes in literature, but he did not complete a degree in either subject. In 1896 Chesterton began working for the London publisher Redway, and T. Fisher Unwin, where he remained until 1902. During this period he also undertook his first journalistic work as a freelance art and literary critic. In 1901 he married Frances Blogg, to whom he remained married for the rest of his life. In 1902 the Daily News gave him a weekly opinion column, followed in 1905 by a weekly column in The Illustrated London News, for which he continued to write for the next thirty years.

Chesterton was baptized at the age of one month into the Church of England,[7] though his family themselves were irregularly practising Unitarians.[8] According to Chesterton, as a young man he became fascinated with the occult and, along with his brother Cecil, experimented with Ouija boards.[9]

Chesterton credited his wife Frances with leading him back to Anglicanism, though he began to see Anglicanism as a "pale imitation". He entered full communion with the Roman Catholic Church in 1922.[10]

Chesterton early showed a great interest in and talent for art. He had planned to become an artist and his writing shows a vision that clothed abstract ideas in concrete and memorable images. Even his fiction seemed to be carefully concealed parables. Father Brown is perpetually correcting the incorrect vision of the bewildered folks at the scene of the crime and wandering off at the end with the criminal to exercise his priestly role of recognition and repentance. For example, in the story "The Flying Stars", Father Brown entreats the character Flambeau to give up his life of crime: "There is still youth and honour and humour in you; don't fancy they will last in that trade. Men may keep a sort of level of good, but no man has ever been able to keep on one level of evil. That road goes down and down. The kind man drinks and turns cruel; the frank man kills and lies about it. Many a man I've known started like you to be an honest outlaw, a merry robber of the rich, and ended stamped into slime."[11]

Chesterton was a large man, standing 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m) and weighing around 21 stone (130 kg). His girth gave rise to a famous anecdote. During World War I a lady in London asked why he was not "out at the Front"; he replied, "If you go round to the side, you will see that I am."[12] On another occasion he remarked to his friend George Bernard Shaw: "To look at you, anyone would think a famine had struck England". Shaw retorted, "To look at you, anyone would think you have caused it".[13] P. G. Wodehouse once described a very loud crash as "a sound like Chesterton falling onto a sheet of tin".[14]

Chesterton usually wore a cape and a crumpled hat, with a swordstick in hand, and a cigar hanging out of his mouth. He had a tendency to forget where he was supposed to be going and miss the train that was supposed to take him there. It is reported that on several occasions he sent a telegram to his wife Frances from some distant (and incorrect) location, writing such things as "Am in Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?" to which she would reply, "Home".[15] Because of these instances of absent-mindedness and of Chesterton being extremely clumsy as a child, there has been speculation that Chesterton had undiagnosed developmental coordination disorder.[16][citation needed]

Chesterton loved to debate, often engaging in friendly public disputes with such men as George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Bertrand Russell and Clarence Darrow. According to his autobiography, he and Shaw played cowboys in a silent movie that was never released.[17]

Death

Chesterton died of congestive heart failure on the morning of 14 June 1936, at his home in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire. His last known words were a greeting spoken to his wife. The homily at Chesterton's Requiem Mass in Westminster Cathedral, London, was delivered by Ronald Knox on 27 June 1936. Knox said, "All of this generation has grown up under Chesterton's influence so completely that we do not even know when we are thinking Chesterton."[18] He is buried in Beaconsfield in the Catholic Cemetery. Chesterton's estate was probated at £28,389, approximately equivalent in 2012 terms to £1.3 million.[19]

Near the end of his life he was invested by Pope Pius XI as Knight Commander with Star of the Papal Order of St. Gregory the Great (KC*SG).[20] The Chesterton Society has proposed that he be beatified.[21]

Writing

Chesterton wrote around 80 books, several hundred poems, some 200 short stories, 4000 essays, and several plays. He was a literary and social critic, historian, playwright, novelist, Catholic theologian[22][23] and apologist, debater, and mystery writer. He was a columnist for the Daily News, the Illustrated London News, and his own paper, G. K.'s Weekly; he also wrote articles for the Encyclopædia Britannica, including the entry on Charles Dickens and part of the entry on Humour in the 14th edition (1929). His best-known character is the priest-detective Father Brown,[3] who appeared only in short stories, while The Man Who Was Thursday is arguably his best-known novel. He was a convinced Christian long before he was received into the Catholic Church, and Christian themes and symbolism appear in much of his writing. In the United States, his writings on distributism were popularized through The American Review, published by Seward Collins in New York.

Of his nonfiction, Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1906) has received some of the broadest-based praise. According to Ian Ker (The Catholic Revival in English Literature, 1845–1961, 2003), "In Chesterton's eyes Dickens belongs to Merry, not Puritan, England" ; Ker treats Chesterton's thought in Chapter 4 of that book as largely growing out of his true appreciation of Dickens, a somewhat shop-soiled property in the view of other literary opinions of the time.

Chesterton's writings consistently displayed wit and a sense of humour. He employed paradox, while making serious comments on the world, government, politics, economics, philosophy, theology and many other topics.[24][25]

Views and contemporaries

Chesterton's writing has been seen by some analysts as combining two earlier strands in English literature. Dickens' approach is one of these. Another is represented by Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw, whom Chesterton knew well: satirists and social commentators following in the tradition of Samuel Butler, vigorously wielding paradox as a weapon against complacent acceptance of the conventional view of things.

Chesterton's style and thinking were all his own, however, and his conclusions were often opposed to those of Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw. In his book Heretics, Chesterton has this to say of Wilde: "The same lesson [of the pessimistic pleasure-seeker] was taught by the very powerful and very desolate philosophy of Oscar Wilde. It is the carpe diem religion; but the carpe diem religion is not the religion of happy people, but of very unhappy people. Great joy does not gather the rosebuds while it may; its eyes are fixed on the immortal rose which Dante saw."[26] More briefly, and with a closer approximation of Wilde's own style, he writes in Orthodoxy concerning the necessity of making symbolic sacrifices for the gift of creation: "Oscar Wilde said that sunsets were not valued because we could not pay for sunsets. But Oscar Wilde was wrong; we can pay for sunsets. We can pay for them by not being Oscar Wilde."

Chesterton and Shaw were famous friends and enjoyed their arguments and discussions. Although rarely in agreement, they both maintained good will toward and respect for each other. However, in his writing, Chesterton expressed himself very plainly on where they differed and why. In Heretics he writes of Shaw:

After belabouring a great many people for a great many years for being unprogressive, Mr. Shaw has discovered, with characteristic sense, that it is very doubtful whether any existing human being with two legs can be progressive at all. Having come to doubt whether humanity can be combined with progress, most people, easily pleased, would have elected to abandon progress and remain with humanity. Mr. Shaw, not being easily pleased, decides to throw over humanity with all its limitations and go in for progress for its own sake. If man, as we know him, is incapable of the philosophy of progress, Mr. Shaw asks, not for a new kind of philosophy, but for a new kind of man. It is rather as if a nurse had tried a rather bitter food for some years on a baby, and on discovering that it was not suitable, should not throw away the food and ask for a new food, but throw the baby out of window, and ask for a new baby.[27]

Shaw represented the new school of thought, modernism, which was rising at the time. Chesterton's views, on the other hand, became increasingly more focused towards the Church. In Orthodoxy he writes: "The worship of will is the negation of will... If Mr. Bernard Shaw comes up to me and says, 'Will something', that is tantamount to saying, 'I do not mind what you will', and that is tantamount to saying, 'I have no will in the matter.' You cannot admire will in general, because the essence of will is that it is particular."[28]

This style of argumentation is what Chesterton refers to as using 'Uncommon Sense' — that is, that the thinkers and popular philosophers of the day, though very clever, were saying things that were nonsensical. This is illustrated again in Orthodoxy: "Thus when Mr. H. G. Wells says (as he did somewhere), 'All chairs are quite different', he utters not merely a misstatement, but a contradiction in terms. If all chairs were quite different, you could not call them 'all chairs'."[29] Or, again from Orthodoxy:

The wild worship of lawlessness and the materialist worship of law end in the same void. Nietzsche scales staggering mountains, but he turns up ultimately in Tibet. He sits down beside Tolstoy in the land of nothing and Nirvana. They are both helpless — one because he must not grasp anything, and the other because he must not let go of anything. The Tolstoyan's will is frozen by a Buddhist instinct that all special actions are evil. But the Nietzscheite's will is quite equally frozen by his view that all special actions are good; for if all special actions are good, none of them are special. They stand at the crossroads, and one hates all the roads and the other likes all the roads. The result is — well, some things are not hard to calculate. They stand at the cross-roads.[30]

Another contemporary and friend from schooldays was Edmund Bentley, inventor of the clerihew. Chesterton himself wrote clerihews and illustrated his friend's first published collection of poetry, Biography for Beginners (1905), which popularized the clerihew form. Chesterton was also godfather to Bentley's son, Nicolas, and opened his novel The Man Who Was Thursday with a poem written to Bentley.

Chesterton faced unfounded erroneous accusations of anti-Semitism during his lifetime, as well as posthumously by anti-Catholic secular Progressives.[31] In a work of 1917, titled A Short History of England, Chesterton considers the year of 1290, when, by royal decree, Edward I expelled Jews from England, a policy that remained in place until 1655. In writing of the official expulsion and banishment of 1290, Chesterton writes that Edward I was a "just and conscientious" monarch, never more truly representative of his people than when he expelled the Jews, "as powerful as they are unpopular". Chesterton writes Jews were "capitalists of their age" so that when Edward "flung the alien financiers out of the land", he acted as "knight errant", and "tender father of his people".[32] In The New Jerusalem, Chesterton made it clear that he believed that there was a "Jewish Problem" in Europe, in the sense that he believed that Jewish culture (not Jewish ethnicity) separated itself from the nationalities of Europe.[33] He suggested the formation of a Jewish homeland as a solution, and was later invited to Palestine by Jewish Zionists who saw him as an ally in their cause.

In his 1989 biography of Chesterton, Gilbert: The Man who was G.K. Chesterton, Michael Coren quoted the Wiener Library as having said that they had never thought of Chesterton "as a man who was seriously anti-semitic".[34] In 2010, the then director of the Wiener Library denied that either the library or anyone authorised to speak on its behalf had ever issued such statement.[35] In September 2013, following a discussion of the issue on twitter, Coren stated that the disputed quotation had come from a 1985 conversation with a librarian whom he did not name.[36] Although he did not explicitly withdraw his attribution of the quotation to the Wiener Library, neither did he provide any justification for regarding the unnamed librarian's opinions as being those of the library's.

Chesterton, like Belloc, openly expressed his abhorrence of Hitler's rule almost as soon as it started.[37]

The Chesterbelloc

- See Also G. K.'s Weekly.

Chesterton is often associated with his close friend, the poet and essayist Hilaire Belloc.[38] George Bernard Shaw coined the name Chesterbelloc[39] for their partnership,[40] and this stuck. Though they were very different men, they shared many beliefs;[41] Chesterton eventually joined Belloc in the Catholic faith, and both voiced criticisms of capitalism and socialism.[42] They instead espoused a third way: distributism.[43] G. K.'s Weekly, which occupied much of Chesterton's energy in the last 15 years of his life, was the successor to Belloc's New Witness, taken over from Cecil Chesterton, Gilbert's brother, who died in World War I.

Legacy

Literary

- Chesterton's The Everlasting Man contributed to C. S. Lewis's conversion to Christianity. In a letter to Sheldon Vanauken (14 December 1950)[44][page needed] Lewis calls the book "the best popular apologetic I know",[45] and to Rhonda Bodle he wrote (31 December 1947)[46][page needed] "the [very] best popular defence of the full Christian position I know is GK Chesterton's The Everlasting Man". The book was also cited in a list of 10 books that "most shaped his vocational attitude and philosophy of life".[47]

- Chesterton was a very early and outspoken critic of eugenics. Eugenics and Other Evils represents one of the first book length oppositions to the Eugenics movement that began to gain momentum in England during the early 1900s.[48]

- Chesterton's 1906 biography of Charles Dickens was largely responsible for creating a popular revival for Dickens's work as well as a serious reconsideration of Dickens by scholars.[49]

- Chesterton's novel The Man Who Was Thursday inspired the Irish Republican leader Michael Collins with the idea: "If you didn't seem to be hiding nobody hunted you out."[50]

- Etienne Gilson praised Chesterton's Aquinas volume as follows: "I consider it as being, without possible comparison, the best book ever written on Saint Thomas... the few readers who have spent twenty or thirty years in studying St. Thomas Aquinas, and who, perhaps, have themselves published two or three volumes on the subject, cannot fail to perceive that the so-called 'wit' of Chesterton has put their scholarship to shame."[51]

- Chesterton's column in the Illustrated London News on September 18, 1909 had a profound effect on Mahatma Gandhi. P. N. Furbank asserts that Gandhi was "thunderstruck" when he read it,[52] while Martin Green notes that "Gandhi was so delighted with this that he told Indian Opinion to reprint it."[53]

- Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, author of seventy books, identified Chesterton as the stylist who had the greatest impact on his own writing, stating in his autobiography Treasure in Clay "The greatest influence in writing was G. K. Chesterton who never used a useless word, who saw the value of a paradox, and avoided what was trite."[54]

- Canadian Media Guru Marshall McLuhan was heavily influenced by Chesterton; McLuhan said the book What's Wrong with the World changed his life in terms of ideas and religion.[55]

- Neil Gaiman has stated that he grew up reading Chesterton in his school's library, and that The Napoleon of Notting Hill was an important influence on his own book Neverwhere, which used a quote from it as an epigraph. Gaiman also based the character Gilbert, from the comic book The Sandman, on Chesterton,[56] and the novel he co-wrote with Terry Pratchett is dedicated to him.

- Argentine author and essayist Jorge Luis Borges cited Chesterton as a major influence on his own fiction. In an interview with Richard Burgin during the late 1960s, Borges said, "Chesterton knew how to make the most of a detective story."[57]

- Chesterton's fence is the principle that you should never take a fence down until you know the reason why it was put up. The paraphrased quotation, was ascribed to Chesterton by John F. Kennedy in a 1945 notebook. The correct quotation is from Chesterton’s 1929 book, The Thing, in the chapter entitled, “The Drift from Domesticity”: "In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it."[58]

Radio

In 1931, the BBC, who believed Chesterton would be "a tremendous success at the microphone", invited him to give a series of radio talks.

Chesterton accepted, tentatively at first. However, from 1932 until his death, he delivered over 40 talks per year. His talks were scripted, but he was allowed (and encouraged) to improvise. It was remarked that his talks had an intimate character to them, in part because they were spoken to his wife and secretary, who were allowed to sit with him during his broadcasts.[59]

The talks were very popular. A BBC official remarked, after Chesterton's death, that "in another year or so, he would have become the dominating voice from Broadcasting House."[60]

Other

- The American Chesterton Society was founded in 1996 to explore and promote his writings:[61]

- In 2008, a Catholic high school, Chesterton Academy, opened in the Minneapolis area.

- In 2012, a crater on the planet Mercury was named Chesterton after the author.[62]

- A fictionalized GK Chesterton is the central character in the Young Chesterton Chronicles, a series of young adult adventure novels written by John McNichol, and published by Sophia Institute Press and Bezalel Books.

Gallery

-

Chesterton at the time of his engagement, 1898

-

Chesterton, by James Craig Annan, 1912

-

Chesterton, by James Craig Annan, 1912

-

G. K. Chesterton with wife Frances

-

Chesterton, by Herbert Lambert, 1920's

-

Chesterton sitting with a dog

Major works

- Chesterton, Gilbert Keith (1904), Ward, M (ed.), The Napoleon of Notting Hill, UK: DMU.

- ——— (1905), Heretics, Project Gutenberg, ISBN 978-0-7661-7476-4.

- ——— (1906), Charles Dickens: A Critical Study.

- ——— (1908a), The Man Who Was Thursday.

- ——— (1908b), Orthodoxy.

- ——— (July 6, 2008) [1911a], The Innocence of Father Brown, Project Gutenberg's.

- ——— (1911b), Ward, M (ed.), The Ballad of the White Horse, UK: DMU.

- ——— (1912), Manalive.

- ———, Father Brown (short stories) (detective fiction).

- ——— (1920), Ward, M (ed.), The New Jerusalem, UK: DMU.

- ——— (1922), .

- ——— (1923), Saint Francis of Assisi.

- ——— (1925), The Everlasting Man.

- ——— (1933), Saint Thomas Aquinas.

- ——— (1936), The Autobiography.

- ——— (1950), Ward, M (ed.), The Common Man, UK: DMU.

Articles

|

|

|

Short stories

- “The Crime of the Communist,” Collier’s Weekly, July 1934.

- “The Three Horsemen,” Collier’s Weekly, April 1935.

- “The Ring of the Lovers,” Collier’s Weekly, April 1935.

- “A Tall Story,” Collier’s Weekly, April 1935.

- “The Angry Street – A Bad Dream,” Famous Fantastic Mysteries, February 1947.

Miscellany

- Elsie M. Lang, Literary London, with an Introduction by G. K. Chesterton, T. Werner Laurie, 1906.

- C. Creighton Mandell, Hilaire Belloc: The Man and his Work, with an Introduction by G. K. Chesterton, Methuen & Co., 1916.

- Harendranath Maitra, Hinduism: The World-Ideal, with an Introduction by G. K. Chesterton, Cecil Palmer & Hayward, 1916.

- Maxim Gorki, Creatures that Once Were Men, with an Introduction by G. K. Chesterton, The Modern Library, 1918.

- Arthur J. Penty, Post-Industrialism, with a Preface by G. K. Chesterton, The Macmillan Company, 1922.

- Henri Massis, Defence of the West, with a Preface by G. K. Chesterton, Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1928.

Notes

- ^ "Obituary", Variety, June 17, 1936

- ^ a b c "Orthodoxologist", Time, October 11, 1943, retrieved 2008-10-24.

- ^ a b O'Connor, John. Father Brown on Chesterton, Frederick Muller Ltd., 1937.

- ^ Douglas 1974: "Like his friend Ronald Knox he was both entertainer and Christian apologist. The world never fails to appreciate the combination when it is well done; even evangelicals sometimes give the impression of bestowing a waiver on deviations if a man is enough of a genius."

- ^ Illustrated London News, 1924-04-19

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help). - ^ Ker 2011. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFKer2011 (help)

- ^ Ker, Ian (2011). G. K, Chesterton: A Biography. Chapter 1: OUP. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-960128-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Ker, Ian (2011). G. K, Chesterton: A Biography. Chapter 1: OUP. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-960128-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Chesterton 1936, Chapter IV.

- ^ "GK Chesterton's Conversion Story", Socrates 58 (World Wide Web log), Google, 2007

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help). - ^ Chesterton, G. K. (1911). "The Flying Stars." In The Innocence of Father Brown, London: Cassell & Company, Ltd., p. 118.

- ^ Wilson, A. N. (1984). Hilaire Belloc, Hamish Hamilton, p. 219.

- ^ Cornelius, Judson K. Literary Humour. Mumbai: St Paul's Books. p. 144. ISBN 81-7108-374-9.

- ^ Wodehouse, P.G. (1972), The World of Mr. Mulliner, Barrie and Jenkins, p. 172.

- ^ Ward 1944, chapter XV.

- ^ Biggs, Victoria (2005), "I", Caged in Chaos, Jessica Kingsley.

- ^ Autobiography, London, Hutchinson & Co., Ltd., 1936, pp. 231-235.

- ^ Lauer 1991, p. 25.

- ^ Barker, Dudley. G. K. Chesterton: A Biography, Stein and Day, 1973, p. 287.

- ^ "Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874–1936)", Catholic authors.

- ^ Antonio, Gaspari (2009-07-14). ""Blessed" G. K. Chesterton?: Interview on Possible Beatification of English Author". Zenit: The World Seen From Rome. Rome: Innovative Media. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ Bridges, Horace J. "G. K. Chesterton as Theologian," Ethical Addresses, The American Ethical Union, 1914.

- ^ Caldecott, Stratford. "Was G.K. Chesterton a Theologian?," The Chesterton Review, November 1999 [Rep. by CERC: Catholic Education Research Center.

- ^ Douglas, J. D. "G.K. Chesterton, the Eccentric Prince of Paradox," Christianity Today, January 8, 2001.

- ^ Gray, Robert. "Paradox Was His Doxy," The American Conservative, March 23, 2009.

- ^ Chesterton 1905, chapter 7.

- ^ Chesterton 1905, chapter 4.

- ^ Chesterton 1905, chapter 20.

- ^ Chesterton 1908b, chapter 3.

- ^ Chesterton 1908b, chapter 3.

- ^ "Last orders", The Guardian, 9 April 2005.

- ^ Julius, Anthony (2010), Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Anti-Semitism in England, Oxford University Press, p. 422.

- ^ Chesterton 1920, Chapter 12.

- ^ Coren (2001, p.214)

- ^ Barkow (2010, p.2)

- ^ Coren, (2013)

- ^ Pearce, Joseph (2005). Literary Giants, Literary Catholics. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. p. 95. ISBN 1-58617-077-5.

- ^ McInerny, Ralph. "Chesterbelloc," Catholic Dossier, May/June 1998.

- ^ Shaw, George Bernard. "Belloc and Chesterton," The New Age, Vol. II, No. 16, February 15, 1908.

- ^ Lynd, Robert. "Mr. G. K. Chesterton and Mr. Hilaire Belloc." In Old and New Masters, T. Fisher Unwin Ltd., 1919.

- ^ McInerny, Ralph. "The Chesterbelloc Thing," The Catholic Thing, September 30, 2008.

- ^ Wells, H. G. "About Chesterton and Belloc," The New Age, Vol. II, No. 11, January 1908 [Rep. in Social Forces in England and America, 1914].

- ^ "Belloc and the Distributists," The American Review, November 1933.

- ^ Lewis, Clive Staples, A Severe Mercy.

- ^ Letter to Sheldon Vanauken, December 14, 1950.

- ^ Lewis, Clive Staples, The Collected Letters, vol. 2.

- ^ The Christian Century, 6 June 1962.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Ahlquist 2006, p. 286.

- ^ Forester, Margery (2006). Michael Collins – The Lost Leader, Gill & MacMillan, p. 35.

- ^ Gilson, Etienne, "Letter to Chesterton's editor", in Pieper, Josef (ed.), Guide to Thomas Aquinas, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Furbank, PN (1974), "Chesterton the Edwardian", in Sullivan, John (ed.), GK Chesterton: A Centenary Appraisal, Harper and Row.

- ^ Green, Martin B (2009), Gandhi: Voice of a New Age Revolution, Axios, p. 266.

- ^ Sheen, Fulton J (2008), Treasure in Clay, p. 79.

- ^ Marchand, Philip (1998), Marshall McLuhan: the medium and the messenger: a biography, pp. 28–30.

- ^ Bender, Hy (2000). The Sandman Companion : A Dreamer's Guide to the Award-Winning Comic Series DC Comics, ISBN 1-56389-644-3.

- ^ Burgin, Richard, Conversations with Jorge Luis Borges, p. 35.

- ^ Taking a fence down

- ^ Ker, Ian (2011). G. K. Chesterton: A Biography

- ^ CatholicAuthors.com. Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936)

- ^ The American Chesterton Society

- ^ "Chesterton", Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature, US: Geological Survey, 17 Sep 2012.

Further reading

|

|

External links

- Portraits of GK Chesterton, National Portrait Gallery (London), retrieved 2010-10-28.

- "Archival material relating to G. K. Chesterton". UK National Archives.

- The American Chesterton Society, retrieved 2010-10-28.

- Sociedade Chesterton Brasil, retrieved 2012-12-22.

- Gilbert Magazine, retrieved 2010-10-28, a Chesterton journal.

- "Chesterton", Little flower, UK, retrieved 2010-10-28: parish church in Beaconsfield where Chesterton is buried.

- GK Chesterton, UK, including etexts

- Works by G. K. Chesterton at Project Gutenberg

- Works (audio), LibriVox, retrieved 2010-10-28.

- Works, Internet Archive, retrieved 2010-10-28.

- Template:Worldcat id

- Chesterton, Gilbert Keith, Works, Wikilivres.

- "Works", Online Books, U Penn, retrieved 2010-10-28.

- G. K. Chesterton: Quotidiana

- 1874 births

- 1936 deaths

- 20th-century British novelists

- Alumni of the Slade School of Art

- Alumni of University College London

- Aphorists

- British World War I poets

- Burials in Buckinghamshire

- Christian apologists

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from Anglicanism

- Integrism

- English autobiographers

- English Catholic poets

- English essayists

- English journalists

- English mystery writers

- English fantasy writers

- English novelists

- English poets

- English Roman Catholics

- English short story writers

- G. K. Chesterton

- Members of the Detection Club

- People educated at St Paul's School, London

- People from Kensington

- Roman Catholic theologians

- Roman Catholic writers

- Christian novelists

- Roman Catholic philosophers

- Knights Commander with Star of the Order of St. Gregory the Great

- Critics of Islam