Chuck Philips: Difference between revisions

| Line 144: | Line 144: | ||

{{reflist|33em}} |

{{reflist|33em}} |

||

== External links == |

|||

{{Commons category}} |

{{Commons category}} |

||

Revision as of 22:37, 1 March 2014

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

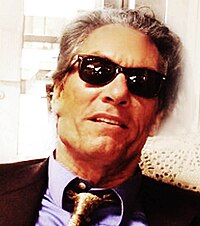

Chuck Philips | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Charles Alan Philips October 15, 1952 |

| Citizenship | US |

| Occupation(s) | Journalist and writer |

| Known for | Exposing crime and corruption in the US music industry |

| Awards | •Pulitzer Prize •George Polk Award •National Association of Black Journalists Award •Los Angeles Press Club award |

| Website | http://www.Chuckphilipspost.com/ |

Charles Alan "Chuck" Philips (born October 15, 1952) is an American writer and investigative journalist.[2] He is best known for his reporting on the music industry for the Los Angeles Times. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his work covering the entertainment business.[2]

Career

Philips did investigative journalism about corruption in the music business.[3] Philips has written for the Los Angeles Times, Rolling Stone, Spin, Village Voice, The Washington Post, Allhiphop.com, the San Francisco Chronicle and Source magazine.[4]

According to Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times, "Chuck was so relentless he would keep knocking on every door of the house – the front door, the side door, the back door, the bathroom window – until he feels he has the answer to his question".[3] Philips wrote about the inner workings of the international music industry, examining censorship,[5] price fixing, payola, ticket scalping, royalty scams, racism, and sexual harassment in the entertainment industry.[6]

Richard D. Barnet and Larry L. Burriss credit Philips' continued reporting on sexual harassment in the music industry with encouraging other media outlets to cover the issue and "bringing sexual harassment in the music industry to a national forum".[7] Philips also covered art and crime, corporate and government corruption, and medical malfeasance. He also focused on investigations into violent crime in the rap music industry. Mark Saylor, Philips's editor at the L.A. Times, said that "Chuck is sort of the world's authority on rap violence."[8]

Early work

Milli Vanilli lip-synching

In 1990, Philips showed that Milli Vanilli, grammy winning-artists, did not sing in their records and were lip-synching in live performances.[9] [non-primary source needed]

Ticketmaster Congressional Hearings

In the early 1990s, Philips wrote a series of stories about Ticketmaster, reporting in 1994 that the rock band Pearl Jam had complained to the Antitrust Division of the United States Department of Justice that Ticketmaster used monopolistic practices and refused to lower service fees for the band's tickets. At the time, Pearl Jam wanted to keep ticket prices under $20 for their fans, with service charges no greater than $1.80. The company had exclusive contracts with large US venues and threatened to take legal action if those contracts were broken.[10]

Hollywood doctors

In 1996, Philips investigated the culture of drug enablement of celebrities like Ozzy Osbourne by Hollywood doctors.[11][non-primary source needed] The series was part of the collection of articles for which he shared the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for Beat Reporting.[12]

Rap crime

Philips has attempted to solve the murders and attacks on black rappers Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls. An early reporter and interviewer of Shakur,[13][14] Philips was a fan. "Philips produced some of the most important research into the crimes against Tupac and Biggie,"[4] said Tony Ortega, editor of the Village Voice. The Huffington Post reported that Philips "has been investigating Tupac's murder for quite some time now."[15]

Murder of The Notorious B.I.G.

In 1997, Philips, along with fellow Los Angeles Times reporter Matt Laitt, reported that the key suspect in the murder of The Notorious B.I.G. was a member of the Crips with a financial motive.[16]

In 2000, Philips recommended that the Los Angeles Times retract an erroneous story the paper ran about the murder of The Notorious B.I.G. The Metro section of the Los Angeles Times published a story claiming that that police suspected a connection between the Notorious B.I.G's death and the Rampart Division police-corruption scandal, a popular theory at the time based the writings of Russell Poole and Randall Sullivan.[8] The Los Angeles Times Metro section ran a photo of Amir Muhammad, identified by police as a mortgage broker unconnected to the murder. Muhammad appeared to match details of the shooter, and the paper printed his name and driver's license number. Philips worked for the Business section of the Los Angeles Times which had been following the Wallace investigation, but he had not heard of the Rampart-Muhammad theory. He searched for Muhammad whom the Metro reporters could not find. It took Philips only three days to find him, and Muhammad came forward to clear his name. The Metro section of the paper was opposed to running a retraction. But the business desk editor Mark Saylor[17] said "Chuck is sort of the world's authority on rap violence,"[8] and advocated, along with Philips, for the paper to run retraction of the article[8] The Los Angeles Times correction article was written by Philips, who quoted Muhammad as saying "I'm a mortgage broker, not a murderer," and asking, "How can something so completely false end up on the front page of a major newspaper?"[18] The story cleared Muhammad's name.[8]

Another key source for Poole's theory was Kevin Hackie who later revealed to Philips that he suffered memory lapses due to psychiatric medications. He had previously testified to knowledge of involvement between Suge Knight, David Mack, and Amir Muhammed but later said that the Wallace attorneys had altered his declarations to include words he never said in pursuing their civil suit against the city of Los Angeles Hackie took full blame for filing a false declaration.[19]

A 2005 story by Philips, showing that the main informant for the Poole/Sullivan theory of Biggie's murder implicating a mortgage broker named Amir Muhammed, David Mack, Suge Knight and the L.A.P.D. was a schizophrenic known as "Psycho Mike" who confessed to hearsay and memory lapses.[20] John Cook of Brill's Content noted that this article "demolished"[21] the Poole-Sullvan theory of Biggie's murder.

Murder of Tupac Shakur

A 2002 two-part series Chuck Philips wrote called "Who Killed Tupac Shakur?" resulted from a year-long investigation, reconstructing the events leading up to Shakur's murder. The articles were based on police affidavits and court documents as well as interviews with investigators, witnesses to the crime and members of the Southside Crips.[22] Philips research showed that "the shooting was carried out by a Compton gang called the Southside Crips to avenge the beating of one of its members by Shakur a few hours earlier. Orlando Anderson, the Crip whom Shakur had attacked, fired the fatal shots. Las Vegas police discounted Anderson as a suspect and interviewed him only once, briefly. He was later killed in an unrelated gang shooting."[22]

The article implicated East Coast music figures, including Christopher "Biggie Smalls" Wallace, Shakur's nemesis at the time, alleging that he paid for the gun.[22] Before their own deaths, Smalls and his family and Anderson denied any role in Shakur's murder. Biggie's family[23] produced documents purporting to show that the rapper was in New York and New Jersey at the time. The New York Times called the documents inconclusive stating:

The pages purport to be three computer printouts from Daddy's House, indicating that Wallace was in the studio recording a song called Nasty Boy on the afternoon Shakur was shot. They indicate that Wallace wrote half the session, was In and out/sat around and laid down a ref, shorthand for a reference vocal, the equivalent of a first take.But nothing indicates when the documents were created. And Louis Alfred, the recording engineer listed on the sheets, said in an interview that he remembered recording the song with Wallace in a late-night session, not during the day. He could not recall the date of the session but said it was likely not the night Shakur was shot. We would have heard about it, Mr. Alfred said."[24]

The second article in Philips's series[25] dissected the murder investigation and detailed how the Las Vegas police department mismanaged the probe and why the homicide remains officially unsolved. His article showed that the specific missteps of the Vegas police: were 1.) discounting the fight that occurred just hours before the shooting, in which Shakur was involved in beating Orlando Anderson in the Las Vegas MGM lobby, 2.) failing to follow up with a member of Shakur's entourage who witnessed the shooting who told Vegas police he could probably identify one or more of the assailants—the witness was killed just weeks later, and 3.) failing to follow-up a lead from a witness who spotted a white Cadillac similar to the car from which the fatal shots were fired and from which the shooters escaped.

At the time of the "Who Killed Tupac Shakur?" series, Russell Poole's alternative theory, implicating Suge Knight was very popular. For many years, Philips withstood attacks by proponents of Poole's theory, including Rolling Stone writer Randall Sullivan, by defenders of Bad Boy records and their affiliates, and more widely in anonymous Internet blogs with withering personal insults such as a photoshop of Philips' head (as taken from the Pulitzer website) onto Suge Knight's arms (as if to imply an intimate relationship).

Philips's series was comprehensively researched, withstanding all attacks. Over the years, moreover, support for Poole's theory waned as new facts came to light supporting Philips's series. As assistant managing editor of the Los Angeles Times, Mark Duvoisin wrote in 2006: "Philips' story has withstood all challenges to its accuracy, ...[and] remains the definitive account of the Shakur slaying."[26]

Attack on Tupac Shakur at Quad Studios

On March 17, 2008, Philips wrote a Los Angeles Times article alleging that thugs had been ordered to beat up Shakur.[27][28] The article was retracted by the Los Angeles Times because it had partially relied on court documents that turned out to be forged, and The Times, Philips, and his editor apologized for the allegations they had made against James "Jimmy Henchman" Rosemond.[29] In 2011, Dexter Isaac admitted that he had attacked Tupac, alleging he did so on orders from Henchman.[30][31][32] Following Isaac's public confession, Philips verified that Isaac had been one of the five key unnamed source supporting Philips' 2008 Los Angeles Times article, and he requested an apology from the Los Angeles Times.[3]

Investigative website

On September 13, 2012, the anniversary of Shakur's death, Philips announced he would conduct a "Twitter experiment," tweeting a 1,200-word article, 40 characters at a time, published concurrently with the launch of his website, the Chuckphilipspost.com.[33] The article was about Harlem drug dealer Eric “Von Zip” Martin and his connection to Sean "Diddy" Combs.[34][35]

In October 2012, the Chuck Philips Post examined the death of a woman while in the custody of the LAPD and the efforts of civil rights lawyer Benjamin Crump to get the LAPD to release dashboard video footage of the arrest.[36]

Awards

In 1999, he won the Pulitzer Prize for Beat Reporting[37] with colleague Michael Hiltzik of the Los Angeles Times for a year-long series that exposed corruption in the music business in three different areas: The Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences raising money for an ostensible charity that netted only pennies on the dollar for its charity, radio station payola for airplay of new recordings, and medical malfeasance in the entertainment industry.[12][17] Mark Saylor, then entertainment editor of the business section of the paper, said it was especially rewarding because it recognized "aggressive reporting on the hometown industry...where The LA Times has long labored under a cloud, the misperception that...[they]...were soft on the entertainment industry".[12]

Philips won the George Polk Award for investigative reporting about black art and culture in America in 1996[2][38] and the National Association of Black Journalists Award for his coverage of the rap music business in 1997.[39]

He won the Los Angeles Press Club award for stories about censorship in 1990.[2]

Personal life

Philips grew up in the Detroit area near Hitsville, the home of Motown.[40] The second of four children, his father was a plumber and his mother a homemaker and devout Catholic. As a child, Philips was religious, and loved Gospel music, which sparked his interest in black music and culture.[40] At nineteen, he hitchhiked to Los Angeles to find a career in the music industry and worked a series of menial jobs[40]

He has expressed outrage at the failure of the police and others to solve the crimes against black figures such as Shakur and Biggie Smalls.[41] He has focused on this task since 2002.[15][42][43]

Philips lives in Los Angeles and edits a news and commentary website, the Chuck Philips Post.

References

- ^ "Chuck Philips vs. Jimmy Henchman – Vengeance in the Verdict". AllHipHop. June 6, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "The 1999 Pulitzer prize winners biography". Pulitzer. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Simone; Romero, Dennis (June 22, 2011). "Chuck Philips demands L.A. Times apology on Tupac Shakur". LA Weekly. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Ortega, Tony. "Foreword to: Tupac Shakur, the LA Times and Why I'm still unemployed". The Village Voice. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Quinn, Eithne (2005). Nuthin' but a "G" Thang: The Culture and Commerce of Gangsta Rap. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12408-2.

- ^

- Becklund Philips, Laurie Chuck (November 3, 1991). "Sexual Harassment Claims Confront Music Industry: Bias: Three record companies and a law firm have had to cope with allegations of misconduct by executives". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- Laursen, Patti (May 3, 1993). "Women in Music". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ Richard D. Barnet; Larry L. Burriss (2001). Controversies of the Music Industry. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 112–4. ISBN 978-0-313-31094-2.

- ^ a b c d e Cook, John (May 23–26, 2000). "Notorious LAT". Brills Content. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (November 16, 1990). "'Girl you know it's true.' It's True: Milli Vanilli Didn't Sing : Pop music: The duo could be stripped of its Grammy after admitting it lip-synced the best-selling 'Girl You Know It's True.'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Budnick, Dean; Baron, Josh (April 24, 2012). Ticket Masters: The Rise of the Concert Industry and How the Public Got Scalped. Penguin Group US. ISBN 978-1-101-58055-4.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (December 7, 2003). "Harsh Reality of 'Osbournes' No Laughing Matter". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ a b c Shaw, David (April 13, 1999). "2 Times Staffers Share Pulitzer for Beat Reporting". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ Sami, Yenigun (July 19, 2013). "20 Years Ago, Tupac Broke Through". National Public Radio.com. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (October 25, 1995). "I am not a gangster". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- ^ a b Makarechi, Kia (June 26, 2012). "James Rosemond, Tupac Shooting: Mogul Reportedly Admits Involvement In 1994 Attack". Huffington Pose. Retrieved July 31, 2012. Cite error: The named reference "Huffington Post on Philips research" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Philips Laitt, Chuck Matt (March 18, 1997). "Personal Dispute Is Focus of Rap Probe". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- ^ a b Trounson, Rebecca (February 22, 2012). "Mark Saylor dies at 58; former Times editor oversaw Pulitzer-winning series". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (May 3, 2000). "Man No Longer Under Scrutiny in Rapper's Death". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (June 20, 2005). "Witness in B.I.G. case says his memory's bad". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (June 3, 2005). "Informant in Rap Star's Slaying Admits Hearsay". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c Philips, Chuck (September 6, 2002). "Who Killed Tupac Shakur?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ Silveran, Stephen M. (September 9, 2002). "B.I.G. Family Denies Tupac Murder Claim". People. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ Leland, John (October 7, 2002). "New Theories Stir Speculation on Rap Deaths". New York Times. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (September 7, 2002). "How Vegas police probe floundered in Tupac Shakur case". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ Duvoisin, Mark (January 12, 2006). "L.A. Times Responds to Biggie Story". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ Samaha, Albert (October 28, 2013). "James Rosemond, Hip-Hop Manager Tied to Tupac Shooting, Gets Life Sentence for Drug Trafficking". Village Voice. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ (Court case exhibit: USA vs James Rosemond Case # 1:11-Cr-00424 May 14, 2012 Document # 100, exhibit 1)

- ^ "Times retracts Shakur story - Page 2 - latimes.com". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ Evans, Jennifer (June 21, 2001). "Hip hop talent agent arrested charged with operating drug ring". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ KTLA News (July 13, 2012). "Convicted Killer Confesses to Shooting West Coast Rapper Tupac Shakur". The Courant. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ Watkins, Greg (June 15, 2011). "Exclusive: Jimmy Henchman Associate Admits to Role in Robbery/Shooting of Tupac; Apologizes To Pac & B.I.G.'s Mothers". Allhiphop.com. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ Starbury, Allen (September 12, 2012). "Writer Chuck Philips To Tweet Article Connecting Diddy To Late Harlem Kingpin 'Von Zip'". Baller Status. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ biz, m (September 18, 2012). "New Tupac Documents; Website Slated to Hit the Internet, Twitter in Honor of Rapper's Death". hiphopnewssource. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ Watkins, Greg (September 13, 2012). "New Tupac Documents; Website Slated To Hit the Internet, Twitter in Honor of Rapper's Death". All Hip Hop. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ Romero, Dennis (October 15, 2012). "LAPD's Alesia Thomas Beating Video Demanded By Attorney Benjamin Crump". LA Weekly.

- ^ "1999 Pulitzer Prize winners for beat reporting". Columbia journalism review. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ Times, Los Angeles (March 7, 1997). "Times Wins Polk Awards for Music Industry, Fund-Raising Stories". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ "1999 Pulitzer prize winners beat reporting". Columbia Journalism review. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ a b c Philips, Philips (June 6, 2012). "Vengeance in the verdict". Allhiphop.com. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ Hogan, Richard Hogan (September 25, 2012). "Chuck Philips on life after the Los Angeles Times". Fishbowl LA/ Mediabistro. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (September 13, 2012). "Tupac Speaks with Chuck Philips: Tapes 1–10". Chuckphilipspost.com. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Garcia-Ajofrin, Isabel (September 25, 2012). "Entrevisa a Chuck Philips: "Ademas de lo de Tupac, Jimmy Henchman orderno disparar al trailer de Snoop Dogg"". Swagga. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- Living people

- 1952 births

- Pulitzer Prize for Beat Reporting winners

- George Polk Award recipients

- American journalists

- American male writers

- Music journalists

- Music writers

- American crime reporters

- American people of Armenian descent

- American writers of Armenian descent

- Writers from Detroit, Michigan

- American investigative journalists

- American newspaper journalists

- American newspaper reporters and correspondents

- American reporters and correspondents

- Tupac Shakur

- Los Angeles Times people

- Writers from Los Angeles, California