Belgian colonial empire: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 605082353 by 69.123.97.248 (talk) RV possible vandalism, edit 1 of 2 |

Undid revision 605082249 by 69.123.97.248 (talk) RV possible vandalism, edit 2 of 2 |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

The ''' |

The '''Belgian colonial empire''' ({{lang-fr|Empire colonial belge}}; {{lang-nl|Belgische koloniale rijk}}), comprised three [[colonialism|colonies]] controlled by [[Belgium]] between 1885 and 1962: [[Belgian Congo]] (now [[Democratic Republic of the Congo]]), [[Ruanda-Urundi]] and a [[Concessions in Tianjin#Belgian concession (1902–1931)|concession in China]]. |

||

The empire was unlike those of the major European imperial powers in that roughly 98% of it was just one colony (about 76 times larger than Belgium)—the Belgian Congo—which had originated as [[Congo Free State|the personal property]] of the country's king, [[Leopold II of Belgium|Leopold II]], rather than being gained through the political or military action of the Belgian state. |

The empire was unlike those of the major European imperial powers in that roughly 98% of it was just one colony (about 76 times larger than Belgium)—the Belgian Congo—which had originated as [[Congo Free State|the personal property]] of the country's king, [[Leopold II of Belgium|Leopold II]], rather than being gained through the political or military action of the Belgian state. |

||

Revision as of 02:10, 23 April 2014

Empire colonial belge Belgische koloniale rijk Belgian colonial empire | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

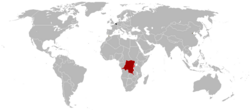

Map of the Belgian colonial empire around 1920. | |

The Belgian colonial empire (Template:Lang-fr; Template:Lang-nl), comprised three colonies controlled by Belgium between 1885 and 1962: Belgian Congo (now Democratic Republic of the Congo), Ruanda-Urundi and a concession in China.

The empire was unlike those of the major European imperial powers in that roughly 98% of it was just one colony (about 76 times larger than Belgium)—the Belgian Congo—which had originated as the personal property of the country's king, Leopold II, rather than being gained through the political or military action of the Belgian state.

Belgians tended to refer to their overseas possessions as 'the colonies' rather than 'the empire'.[1] Unlike other countries of the period with foreign colonies, such as Britain or Germany, Belgium never had a monarch styled 'Emperor'.

Background

The nation of Belgium achieved independence only in 1830. (Immediately prior to that (1815-1830), it had formed part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.) By the time Belgium had consolidated power and considered an overseas empire, major imperial powers such as the United Kingdom and France, and to some degree, Spain, Portugal, and the Netherlands already had staked out the most economically promising territories for colonization within their spheres of influence. In 1843, King Leopold I signed a contract with Ladd & Co. to colonize the Kingdom of Hawaii, but the deal fell apart when Ladd & Co. ran into financial difficulties.[2] Leopold II tried to interest his government in establishing colonies, but it lacked the resources to develop the candidate territories and turned down his plans.

Congo

Congo Free State (1885–1908)

Leopold II acquired the Congo through private acquisition and military force, not through the apparatus of the state. Leopold II exploited the Congo for its natural rubber, which was becoming a valuable commodity. The Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company employed the Force Publique brutally to extract profits from the territory. His regime in the Congo operated the territory as a forced labor colony, using murder and mutilation as punishments for villagers who did not fulfill the quota for and distribute the appropriate amount of rubber. It is estimated that millions of Congolese died during this time.[3] Many of the deaths were attributed to lack of immunity to new diseases introduced by contact with European colonists; it has been estimated that sleeping sickness and smallpox killed nearly half the population in the areas surrounding the lower Congo River.[4]

A reduction of the population of the Congo is noted by all who have compared the country at the beginning of Leopold's control with the beginning of Belgian state rule in 1908, but estimates of the deaths toll vary considerably. The consensus is around ten million Congolese[5][6][7][8] died during the rule of Leopold, accounting for a fifth of the population. As the first census did not take place until 1924, it is difficult to quantify the population loss of the period. William Rubinstein wrote: "More basically, it appears almost certain that the population figures given by Hochschild are inaccurate. There is, of course, no way of ascertaining the population of the Congo before the twentieth century, and estimates like 20 million are purely guesses. Most of the interior of the Congo was literally unexplored if not inaccessible."[9]

Although the Congo Free State was not officially a Belgian colony, the country Belgium was its chief beneficiary, in terms of its trade and the employment of its citizens. Leopold II personally becoming monstrously rich from the rubber and ivory exports of the colony acquired at gunpoint. The wealth Leopold extracted was used to construct numerous fine public buildings in Brussels, Ostend and Antwerp. Today he is remembered in Belgium as the 'Builder-King'. Through the Royal Trust, he sold most of his property to the nation, adding to his fortune.

Belgian Congo (1908–1960)

In 1908, to defuse an international outcry against the brutality of the Congo Free State, the Belgian government agreed to annex it as a colony, which forthwith was named the Belgian Congo. The Belgian parliament had long resisted taking responsibility for the Congo Free State as a colony of Belgium. It also annexed Katanga, a territory held under the Congo Free State, which Leopold had gained in 1891. He had sent an expedition that killed its king, Msiri, cut off his head, and hoisted it on a pole.[10] Leopold had administered Katanga separately, but in 1910 the Belgian government merged it with the Belgian Congo. The Belgian Congo was one of the three colonies occupied by Belgian forces.

The conditions in the Congo improved following the Belgian government's takeover from the Congo Free State. Select Bantu languages were taught in primary schools, a rare occurrence in colonial education. Colonial doctors greatly reduced the spread of African trypanosomiasis, commonly known as sleeping sickness. The colonial administration implemented a variety of economic reforms that focused on the improvement of infrastructure: railways, ports, roads, mines, plantations and industrial areas. The Congolese people, however, lacked political power and faced legal discrimination. All colonial policies were decided in Brussels and Leopoldville. The Belgian Colony-secretary and Governor-general, neither of whom was elected by the Congolese people, wielded absolute power. Among the Congolese people, resistance against their undemocratic regime grew over time. In 1955, the Congolese upper class (the so-called "évolués"), many of whom had been educated in Europe, initiated a campaign to end the inequality.

During World War II, the small Congolese army achieved several victories against the Italians in North Africa.

The Belgian Congo became independent on 30 June 1960 as the Republic of Congo-Léopoldville, and is now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Most of the 100,000 Europeans who had remained behind after independence left the country.[11]

Ruanda-Urundi (1916–1962)

Ruanda-Urundi was a part of German East Africa under Belgian military occupation from 1916 to 1924 in the aftermath of World War I when a military expedition had the Germans out of the colony. It was made a League of Nations class B mandate, allotted to Belgium, from 1924 to 1945. It was designated as a United Nations trust territory, still under Belgian administration, until 1962, when it developed as the independent states of Rwanda and Burundi. After Belgium began administering the colony, it generally maintained the policies established by the Germans, including indirect rule via local Tutsi rulers, and a policy of ethnic identity cards, (a policy later retained in the Republic of Rwanda). Revolts and violence against Tutsi, known as the Rwandan Revolution, occurred in the events before independence.

Tianjin Concession (1902–1931)

Along with several other European powers and the United States, Belgium also gained a Concession (Chinese: zujie 租界) of some few square kilometers in Tianjin, a Chinese Treaty port), as a result of the Boxer Rebellion. This was essentially a trading post, rather than a colony. The region was under Belgian control from 1902 to 1931.

Santo Tomás, Guatemala

Belgium provided support to Rafael Carrera in his leading Guatemala to independence in Central America in 1840, and expanded its influence in that region. On 4 May 1843, the Guatemalan parliament issued a decree giving the district of Santo Tomás "in perpetuity" to the Compagnie belge de colonisation, a private Belgian company under the protection of King Leopold I of Belgium. It replaced the failed British Eastern Coast of Central America Commercial and Agricultural Company.[12] Belgian colonizing efforts in Guatemala ceased in 1854, due to lack of financial means and high fatalities suffered due to yellow fever and malaria, endemic diseases of the tropical climate.[13]

Isola Comacina

In 1919, the Island of Comacina was bequeathed to King Albert I of Belgium for a year, and became an enclave under the sovereignty of Belgium. After a year, it was returned to the Italian State in 1920. The Consul of Belgium and the president of the Academy of Brera established a charitable foundation with the goal of building a village for artists and a hotel.

See also

General:

References

- ^ In Dutch, the name used is 'Belgische koloniën'. In French the term 'Colonies belges' is far more common than 'Empire colonial belge'.

- ^ Report of the proceedings and evidence in the arbitration between the King and Government of the Hawaiian Islands and Ladd & Co., before Messrs. Stephen H. Williams & James F. B. Marshall, arbitrators under compact. C.E. Hitchcock, printer, Hawaiian Government press. 1846.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Religious Tolerance Organisation: The Congo Free State Genocide. Retrieved 14 May 2007.

- ^ John D. Fage, The Cambridge History of Africa: From the earliest times to c. 500 BC, Cambridge University Press, 1982, p. 748. ISBN 0-521-22803-4

- ^ Hochschild.

- ^ Isidore Ndaywel è Nziem. Histoire générale du Congo: De l'héritage ancien à la République Démocratique.

- ^ "Congo Free State, 1885-1908". Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/3516965.stm

- ^ Rubinstein, W. D. (2004). Genocide: a history. Pearson Education. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0-582-50601-8

- ^ De Pont-Jest, René (1892). "L'Expédition du Katanga, d'après les notes de voyage du marquis Christian de Bonchamps". Le Tour du Monde. Retrieved 5 May 2007. See also Christian de Bonchamps.

- ^ "The United Nations and the Congo". Historylearningsite.co.uk. 30 March 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "New Physical, Political, Industrial and Commercial Map of Central America and the Antilles", Library of Congress, World Digital Library, accessed 27 May 2013

- ^ "Santo Tomas de Castilla, Britannica Encyclopedia

Further reading

- Anstey, Roger (1966). King Leopold's Legacy: The Congo under Belgian Rule 1908-1960. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|month=(help) - Nzongola-Ntalaja, Georges (2002). The Congo From Leopold to Kabila: A People's History. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-052-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|coauthors=and|month=(help)